Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

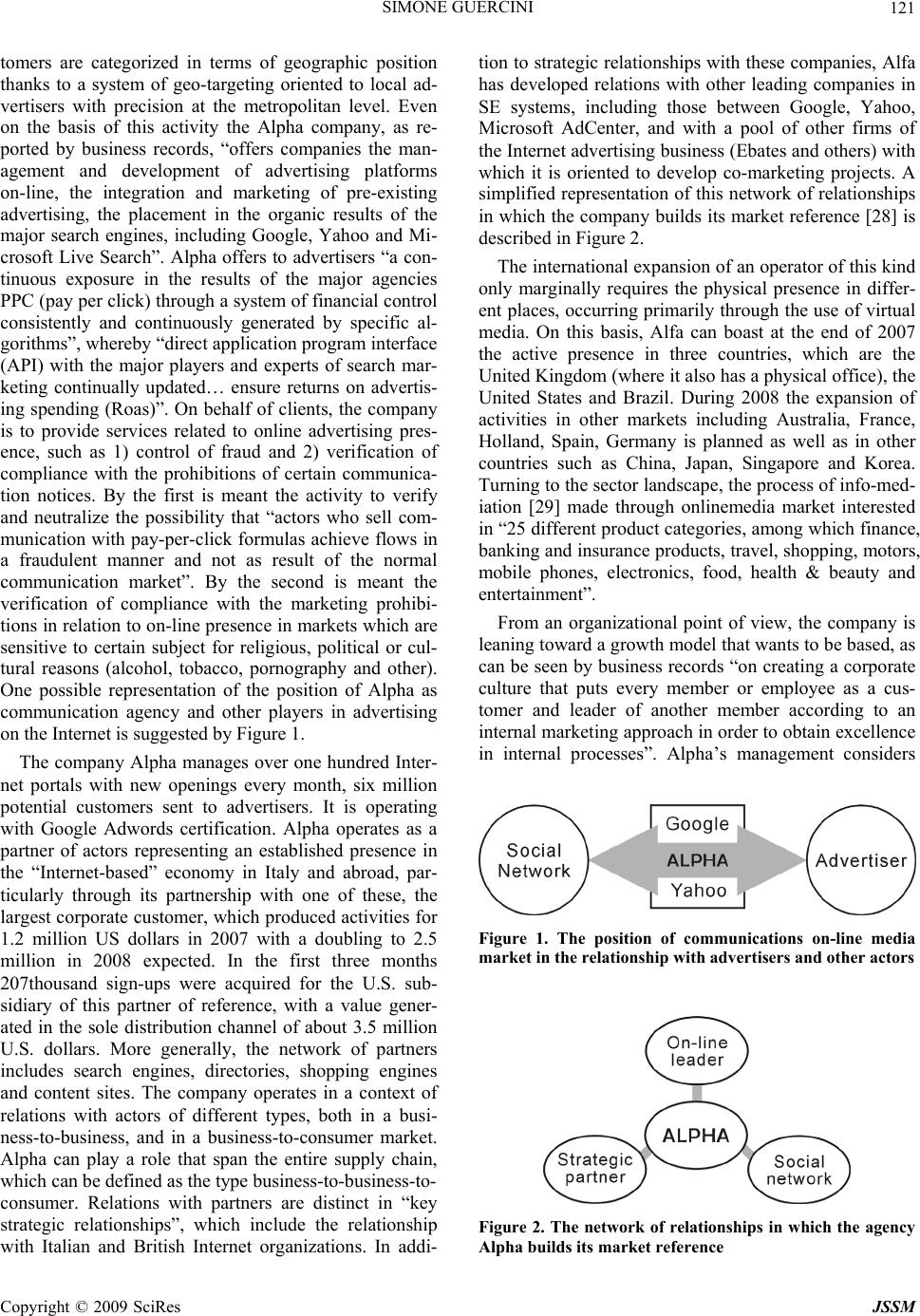

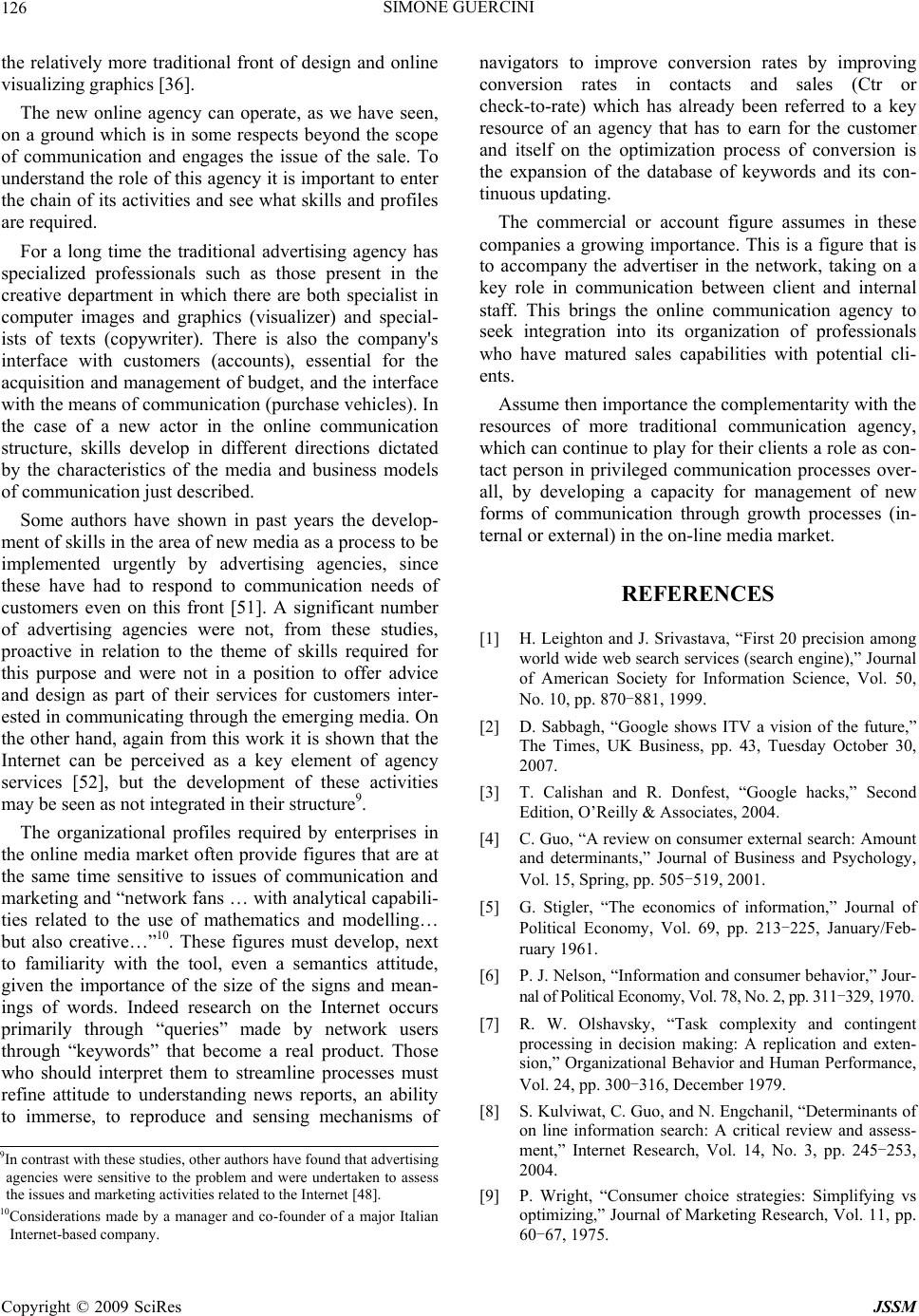

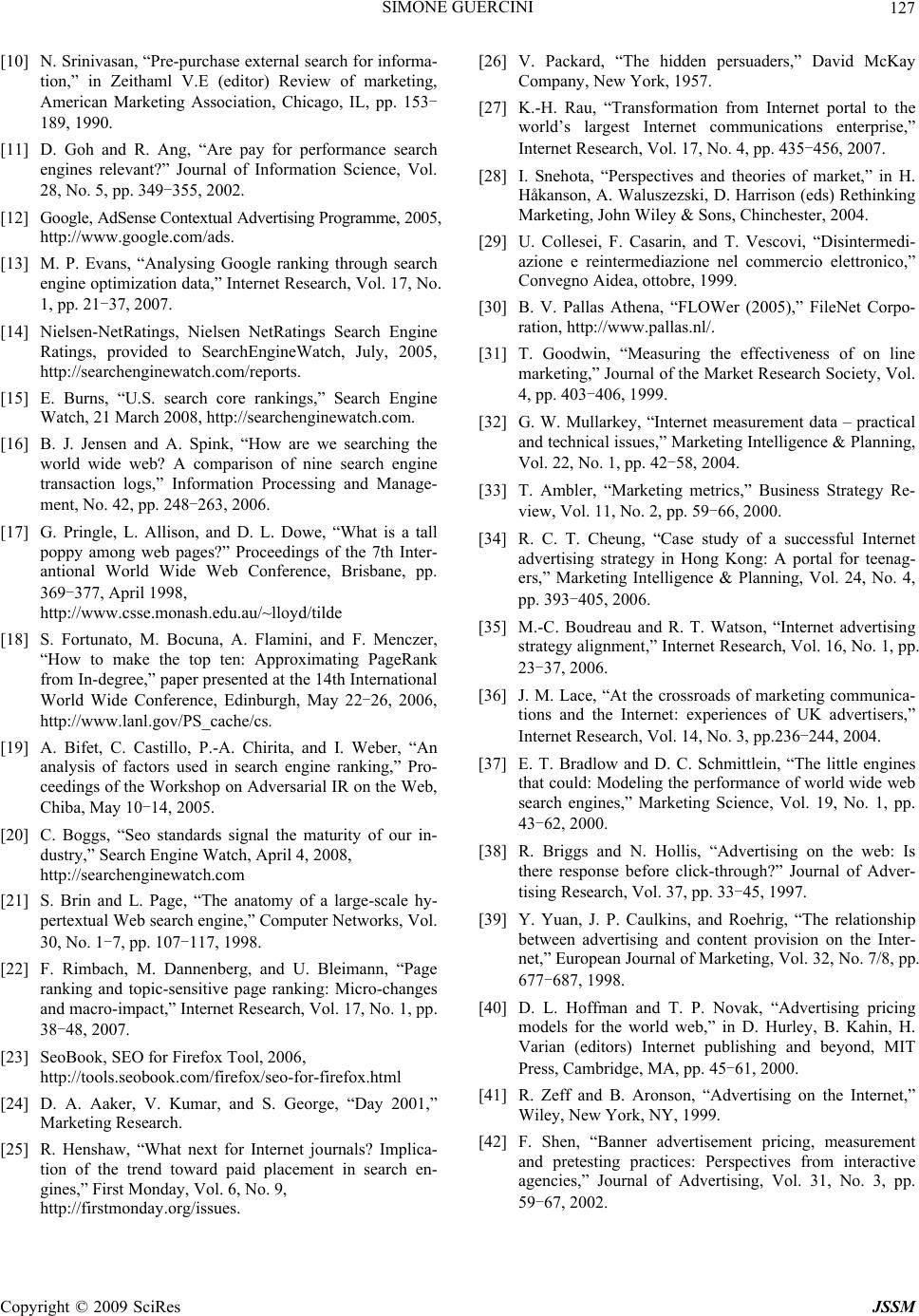

J. Service Science & Management, 2009, 2: 117-128 Published Online June 2009 in SciRes (www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM On Line Media Market and New Advertising Agencies: Analysis of an Italian Case Simone Guercini University of Florence, Florence, Italy. Email: simone.guercini@unifi.it Received August 21st, 2008; revised October 9th, 2008; accepted December 4th, 2008. ABSTRACT This article focuses on the profile of agencies which offer communication services through new media related to the information role of the major search engines systems (like Google, Yahoo and others). In particular, attention is paid to firms operating in that context which are taking an innovative profile when compared to communication agencies linked to traditional media. The article develops the following steps: in a first part the characteristics are taken into consideration through inno- vative communication systems search engines in relation to market trends and the latest configuration of actors linked to them; a second step considers the case of an Italian company acting as an agency in the so-called "online media market", highlighting the type of skills and relationships developed through this; finally in a third part some thoughts on the characteristics of the new communication agencies are proposed in comparison with those of the traditional ad- vertising agencies operating with the help of the more traditional mass media. At the conclusion of the article some implications of the analysis are developed and evaluations are made about the development of new business communication services object of our analysis. Keywords: search engines marketing, advertising agencies 1. Introduction Market trends and communication characteristics of the new media: In recent years the Internet advertising generated the entire growth of the advertising business at least in some major markets. The phenomenon of growth of advertising through search engines is obviously wider than Google and involves other actors1. Alongside these players there are others who take the auxiliary and in- termediaries involved in the market between the “search engine” and communication needs expressed by actors who are often small or lacking the necessary skills. There are two areas of communication, one in which search engine operates and the other traditional media, which are in large part complementary, not least because search engines on the one hand and commercial television or print media on the other operate on advertising markets different in some respects, the first predominantly in the collection and classification (classified), the second in the exposure of companies, brands and products (dis- plays). The growth of Google in other words also tends at least in part to increase the advertising pie, communi- cating in a different and complementary way compared to other players already present. So television and the print media may look like a “brand builder”, while the search engine on the Internet is proposed mainly as a “brand finder” [1]. The same television also hosts in many cases advertising by operators who want to affirm on-line brands (as Ask.com or eBay). Commercial television in many developed countries is losing advertising revenue, but its existence does not appear threatened in the near future. Since commercial television is conducting advertising campaigns for the same brands of companies based on the Internet, televi- sion operators move toward a complementary business, and only they have the opportunity to provide an audi- ence of millions of people to advertisers in one fell swoop. It is also true, however, that Google wants to expand into video advertising and that the battle between television and the Internet for advertising business is still underway [2]. The global success of Google highlights the search engine business as a broad and expanding component of 1The most im p ortant U.S. p la y ers are Yahoo, Microsoft, Aol, Ask.  SIMONE GUERCINI 118 the advertising business, one of the traditionally largest and important in the field of marketing [3]. Information search is one of the main paths in con- sumer behaviour research, but the phenomenon of online research has only recently received more attention [4]. The consumers’ search behavior has been deeply rooted in the information economics [5,6]. The cost-benefit structure derived from information theory is the basis of the explanation for the success of search engines in the functioning of the Internet as a tool of communication in general and especially in gathering information. The search for information is an essential phase of the purchase process, and thus an object of attention in tradi- tional marketing, as more generally in the social sciences [4]. In general terms, the perceived benefits and costs are the two main determinants of the process of seeking in- formation put in place by the purchase decision. The benefits of research information are defined as the results that enhance usefulness or provide value by facilitating the achievement of objectives or a higher value level [7]. According to a model proposed in the literature [8], the benefits of research are to be linked to indicators includ- ing ease of use, effectiveness of research and satisfaction of the user. The perceived cost of information is meas- ured in terms of the economic and psychological effort required in research, and is assessed in relation to factors such as the ability to research, and thus the experience, knowledge, education and preparation coming from peo- ple involved in the process [8]. Of course, other factors are of importance in the information acquisition process entering into relations with benefits and costs arising from this, such as purchasing strategies [9], situational factors, personal factors and motivation to search [10]. Search engines assist Internet users by filtering the excess information available on the world wide web through the concept of “relevancy ranking” (order of importance) in which the research results have been pre- pared in accordance with algorithms that determine how closely a document meets the query made by the user. The criterion used by these classification algorithms var- ies from case to case but typically is based on the char- acteristics of the document, such as the number and fre- quency of terms relevant to the question, the positions in the document and the structure of links [11]. When the world wide web matured, the search engine systems occupied a position of growing power, first in channelling the attention of millions of users, then in generating returns for websites through “contextual ad- vertising programs” as in the case of Google AdSense [12]. Search engines are in a position of power in the online world, as witnessed by the fact that more than half of all visitors come to a website through them rather than a direct link to another web page [13], and taking into account that, together search engine systems processed in 2005 over 4.5 billion queries per month [14], becoming more than ten billion per month in the United States alone by the end of 2007 [15]. These figures explain why a fierce competition is tak- ing place to understand the search behavior of users of search engines. Search engines may return many millions of documents for each possible question, but users are trying to select few of them. Some authors have high- lighted this point through the development of empirical investigations. For example, according to Spink and Jansen [16] 73% of users of search engines never look beyond the first page of results. This explains the interest of advertisers to be included among the sites which are able to seize these positions, and therefore justifies the interest in understanding what factors may influence the “page ranking” in a search engine system, as a crucial factor for each website that wants to attract a large num- ber of users [13]. That interest involves more than the advertisers or the actors who manage websites with the intent to optimize results from the search engine systems, or following a process of search engine optimization. The latter is defined as a process that seeks to place highest a web page or a domain for specific keywords that can be used in queries made by users. The search engines importance creates considerable interest in the arrangements that determine the function- ing and techniques that can be used to improve the effec- tiveness of the ranking of web pages. A study conducted by systems corresponding to InfoSeek, Excite, AltaVista and Lycos, at the end of the nineties [17] showed the importance assumed by the characteristics of informative title, headers, keywords and fields on this page. Recently, with the advent of a prominent position obtained by Google, and attention focused on the algorithms on which the function of this operator is based, and in par- ticular on the algorithm of page ranking (PR) used by it [18,19]. The importance of communication in new media has led to the emergence of a new industry formed by com- panies operating in search engine optimization (Seo). These companies are trying to determine the most im- portant factors that can be used to obtain a high ranking in search results on the SE systems and then applying these factors to the websites of customers in exchange for commissions [20]. Given the nature of consultants and agents of the operators of this industry, its impor- tance to the process of marketing communications and, more generally, communications business, is that players can be seen in relation to traditional advertising agencies and how bidders services potentially substitute to the extent that the new media are substitutes for the tradi- tional media. Despite their increasing number, these companies have only partial information on the heuris- tics used by search engine systems [13]. This informa- Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  SIMONE GUERCINI 119 tion is mainly gained through a process of “trial and er- ror” [18]. The attention to the role of search engines is con- nected to the implications for marketing and sales tech- niques resulting from “page ranking” [21]. The devel- opment and impact of “page ranking” and in particular the “page ranking algorithm” used by search engines, as the “topic sensitive page ranking” (Tspr) allows a fo- cused development of marketing strategies on the Inter- net under current conditions of the electronic market- place. It is therefore important to understand search en- gine optimization systems (or Seo), because the Internet marketing approaches which are developed today are derived from the calculation, the implementation and the impact of these concepts. The phenomena of page ranking and topic sensitive page ranking algorithms ob- tained from the assessment of the structure of which are tied to major Seo strategies. The change in search engine technology shows how these algorithms are becoming increasingly complex, and the comparison to that evolu- tion can take into account only some elements of a phe- nomenon of large-scale change [22]. The literature has identified several factors that may influence the positioning of a website on a search engine ranking system and distinguishes into two categories: 1) factors that refer to the web page, as the existence and frequency of keywords (query-factors); 2) factors which make reference to information from external the web pages that are connected by links to web page in question (query-independent-factors). The contribution of indi- vidual factors linked to both types are difficult to assess since the operators of search engine don’t reveal what they use when determining the ranking of a webpage. These considerations explain why it is difficult to identify the factors involved in an algorithm ranking without a large database of millions of “search engine results pages” (Serp) and without making use of ex- tremely sophisticated data mining. Despite these difficul- ties, there are effective techniques that can be taken to achieve levels of high ranking sites and that have been identified from the best practices used by the most suc- cessful Seo [13]. The analysis process is generally applied to Google, for years the leader among the search engine systems, which already realized in 2005 the 46.2% of all questions of research (queries) produced by users worldwide [14]. This percentage has risen further in the last years to es- tablish a market share for Google that represents the ab- solute majority of clicks made at the international level2. Of the parameters (estimated at over two hundred) that Google references in determining the rank of a page, some were indicated as more effective in recent studies [13]: 1) number of pages in a web site indexed; 2) the page rank of the site3; 3) the number of incoming links to a website (also defined as “inbound hyperlinks”); 4) the age of the domain name of the website; 5) a list of web- sites, other web engine systems and other social net- works [23]. Search engines were classified in systems which pre- vail as “pay-for-performance” and other systems defined as “traditional” ones [11]. The pay-for-performance sys- tems (Pfp) provide search services for documents on the Web giving a rank to documents not only on the basis of the characteristics of content, but also in agreement with investments that owners of a website intended to achieve. In other words, Pfp systems provide a service ranking of web pages in relation solely by the amount of money paid by advertisers for certain keywords and not as de- termined the relevance of the document itself compared to a given query. To make the listing of a site on a Pfp search engine the owner of the site proposed bids on keywords that describe properly the website. The amount will be paid each time a user visits the site when it ap- pears in the list of search results produced by the Pfp system. Generally a higher offer corresponds to higher rankings for the site, and thus a greater probability that the user visits the web site as a result of a query4. The lists provided by Pfp systems are in this sense fully comparable to advertising since they represent an adver- tising product with specific characteristics but similar to others. Some studies have provided data to support that Pfp search engines were less effective in providing qual- ity search results compared to the traditional ones, re- sulting in effects that are tainted by paid work [11]. In particular, these studies highlight how the services pro- vided by Pfp systems respond to serve needs of users compared to traditional engine [11]. It follows that the rest of Pfp systems are somewhat controversial since the user may not be clear which site reported in a higher position in rank is not the most relevant site, but that for which advertisers are willing to pay a greater considera- tion [24,25]. This focuses on the pitfalls associated with new media that can recall nature, although not yet in the proportions, the fears related to forms of advertising pro- posals in the past by media which have today become traditional [26]. 2In the United States in February 2008 were carried out about 10 billion of questions, which the 59.2% (5.9 billion) carried out on Google, 21.6% (2.1 billion) implemented on Yahoo, and remainder on other search engine, the most important of which are Microsoft, Ask and Aol [15]. 3In this case the term “page ranking” does not want to indicate the final result of indexation made by the search engine, but the result of a gen- eral algorithm which is known to staff area which is described in Rimbach et al. [22]. 4Among the search engine systems returned to the Pfp model are men- tioned in the literature cases of Overture, FindWhat, Sprinks, the first case is the subject of a comparison with Google, the latter interpreted b y some authors as a search engine and not linked to models Pfp and in this sense “traditional” [11]. In any case the variety of search engines and the dif- ferentiation of algorithms accessible is itself a value. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  SIMONE GUERCINI 120 While the development of high quality pages is very good for users, this is not conducive to the appearance of diversification, which is itself an element of security for the user. In other words, the presence of several types of search engine systems goes against the homogenization trend of the available information, which could indicate sites actually more relevant but is not certain to be fa- vorable to users who turn to search engines to acquire information [22]. 2. The Case of the New Advertising Agency in the Italian On-Line Media Market The importance of the new advertising and communica- tion context above described is confirmed by the emer- gence of a new wave of companies that assume the role of intermediaries, auxiliaries and consultants in commu- nication processes related to search engine systems (SE) and generally to the Internet advertising. These realities are now increasingly present and also relevant in Italy in addition to the international level. Search engines are working on two main objectives to support its develop- ment: 1) identify the optimum information for a search conducted by users; 2) effectively and efficiently manage the index produced by their algorithms and that translates in the “search engine ranking page” or Serp. While search engines used technologies with increasing success to identify complex web pages relevant to a question (query), all the strategies of the actors as agencies or as consultants for the optimization of the statement of ad- vertisers on the Internet (or search engine optimisator – Seo) operate through heuristic tools to achieve this result, such as taking the initiative to build highly relevant web pages. The case described in this paper is a SEO named “Al- pha” for confidentiality reasons. This is a company founded in July 2006 with offices in an Italian city as well as in London, which has as its mission to “industri- alize the processes of the value chain in on-line advertis- ing for the benefit of all Internet users and quality of their research” coming to “implement the processes of global companies by world leaders which can be con- trolled to maximize the return on investment of advertis- ers… offering solutions and specific opportunities to each market”5. The definition of return on advertising spending (Roas) assumes the characteristic of key con- cept in justifying the presence of actors like Alpha. Al- pha is one of the “optimizers, converters, distributors of information on behalf of advertisers in the on-line media market”. This company is a strongly oriented to growth so that, despite the recent origin, it is expected by 2009 to speak “14 different languages, providing information as precise and ideal solutions to users, guiding them to investors as buyers of high potential purchase”6. The parameters of this agency have followed a trend of rapid growth. Created in July 2006, the company counts at the end of 2006 two employees and produces the first 500,000 euros of turnover. At the end of 2007 there are 6 full-time employees, plus some external con- sultants, and the share turnover reached 3.7 million euros. This dynamism is reflected in the values described in the documents of external communication, which include “transform ideas and opportunities in winning models, international business and change in speed, high en- hancement of each individual user”. The company is geared to achieve media planning and media buying on the Internet. According to business records the company is to monitor about 60 thousand potential customers, who are brought into contact with companies that provide goods or services they are looking for and with advertis- ers who spend over half a million U.S. dollars each month. Overall, the company operates in the field of “search marketing”, the context in which the develop- ment of technology platforms with exclusive rights and the creation of high traffic portals gave quick access to international markets both in America and Europe. In this context Alfa operates as an agency engaged in a steady growth in partnerships with stakeholders in the sector, an aspect for which a significant dimension of the considerable financial credibility is assumed. Among the activities carried out by this company is including the creation of web platforms and e-commerce at local and global multi-language management, with direct relation- ships with agencies that were operating in early 2008 in six countries speaking four different languages. The firm tries to develop technologies for managing statistical and automated control of know-how around both qualitative and quantitative basic marketing. Various sources testify to the growing importance that players offering “digital services” are to have in the for- mulation of new “communication systems” [27]. By digital services is meant the types of corporate services that are ordered, delivered, used and paid in full on the Internet (from logos and ring tones, lotteries, SMS, de- velopment of pages online…) up to the inclusion of competitive services for actors to other areas of commu- nication as mobile call-by-call [27]. The product supplied by Alpha includes the develop- ment of lists of contextual inventories for individual markets, categories and products. The production of this database with characteristics of portfolio information is constantly being developed and updated with the idea of making the company a “dynamic zeitgeist and a constant mirror of the new trends of the moment”. Potential cus- 5The considerations given in quotes are taken from “2008 company profile” of the company Alfa. 6The p assa g es in q uotes are taken from business records. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  SIMONE GUERCINI 121 tomers are categorized in terms of geographic position thanks to a system of geo-targeting oriented to local ad- vertisers with precision at the metropolitan level. Even on the basis of this activity the Alpha company, as re- ported by business records, “offers companies the man- agement and development of advertising platforms on-line, the integration and marketing of pre-existing advertising, the placement in the organic results of the major search engines, including Google, Yahoo and Mi- crosoft Live Search”. Alpha offers to advertisers “a con- tinuous exposure in the results of the major agencies PPC (pay per click) through a system of financial control consistently and continuously generated by specific al- gorithms”, whereby “direct application program interface (API) with the major players and experts of search mar- keting continually updated… ensure returns on advertis- ing spending (Roas)”. On behalf of clients, the company is to provide services related to online advertising pres- ence, such as 1) control of fraud and 2) verification of compliance with the prohibitions of certain communica- tion notices. By the first is meant the activity to verify and neutralize the possibility that “actors who sell com- munication with pay-per-click formulas achieve flows in a fraudulent manner and not as result of the normal communication market”. By the second is meant the verification of compliance with the marketing prohibi- tions in relation to on-line presence in markets which are sensitive to certain subject for religious, political or cul- tural reasons (alcohol, tobacco, pornography and other). One possible representation of the position of Alpha as communication agency and other players in advertising on the Internet is suggested by Figure 1. The company Alpha manages over one hundred Inter- net portals with new openings every month, six million potential customers sent to advertisers. It is operating with Google Adwords certification. Alpha operates as a partner of actors representing an established presence in the “Internet-based” economy in Italy and abroad, par- ticularly through its partnership with one of these, the largest corporate customer, which produced activities for 1.2 million US dollars in 2007 with a doubling to 2.5 million in 2008 expected. In the first three months 207thousand sign-ups were acquired for the U.S. sub- sidiary of this partner of reference, with a value gener- ated in the sole distribution channel of about 3.5 million U.S. dollars. More generally, the network of partners includes search engines, directories, shopping engines and content sites. The company operates in a context of relations with actors of different types, both in a busi- ness-to-business, and in a business-to-consumer market. Alpha can play a role that span the entire supply chain, which can be defined as the type business-to-business-to- consumer. Relations with partners are distinct in “key strategic relationships”, which include the relationship with Italian and British Internet organizations. In addi- tion to strategic relationships with these companies, Alfa has developed relations with other leading companies in SE systems, including those between Google, Yahoo, Microsoft AdCenter, and with a pool of other firms of the Internet advertising business (Ebates and others) with which it is oriented to develop co-marketing projects. A simplified representation of this network of relationships in which the company builds its market reference [28] is described in Figure 2. The international expansion of an operator of this kind only marginally requires the physical presence in differ- ent places, occurring primarily through the use of virtual media. On this basis, Alfa can boast at the end of 2007 the active presence in three countries, which are the United Kingdom (where it also has a physical office), the United States and Brazil. During 2008 the expansion of activities in other markets including Australia, France, Holland, Spain, Germany is planned as well as in other countries such as China, Japan, Singapore and Korea. Turning to the sector landscape, the process of info-med- iation [29] made through onlinemedia market interested in “25 different product categories, among which finance, banking and insurance products, travel, shopping, motors, mobile phones, electronics, food, health & beauty and entertainment”. From an organizational point of view, the company is leaning toward a growth model that wants to be based, as can be seen by business records “on creating a corporate culture that puts every member or employee as a cus- tomer and leader of another member according to an internal marketing approach in order to obtain excellence in internal processes”. Alpha’s management considers Figure 1. The position of communications on-line media market in the relationship with advertisers and other actors Figure 2. The network of relationships in which the agency Alpha builds its market reference Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  SIMONE GUERCINI 122 that “the central unit contributes to the systematic control and strategic development management and planning in support of operations of trading on-line on an industrial scale, implementing a policy of risk control-oriented lobbying for new partnerships, in the maintenance of operating margins in each operation”. In this context the organization, young and still small, is experiencing an elaborate articulation of business functions and organiza- tional responsibility. In the managers’ view the large sized actors are able to directly apply to the major search engines like Google to propose its own advertising budget and directly manage an optimization process of the contacts with users mov- ing on the Internet. For smaller actors with limited budg- ets, direct contact with Google could be more difficult, especially because the latter actor could not find interest in a direct relationship. Nonetheless, these players can conveniently produce communication through search engines, working relationship with agencies that can in- terface and above all have the know-how to assess the performance and then optimize the conditions for the cost of communication through the new media. When it comes to optimizing it refers to the conversion of con- tacts in purchases of product, and then calculate the cost of acquisition (Coa). Some operators may in fact simply navigate to define a margin on each unit of product / service sold as a result of the communication system built by the search engine. As highlights one of the co-founders of Alpha there “may have operators who establish how much they can spend on each unit of product sold through the search engine advertising … for example, an advertiser can define a Coa of 4 U.S. dollars and declare they can spend on advertising up to that amount for each unit of output sold…”. Having said that the actor who holds himself out as an advertising agency or should orient itself to respond to the advertiser track- ing in almost instantaneous terms which is his return on advertising spending (Roas). To achieve its role as the optimizer, the online communication agency must act by developing and verifying knowledge on the conversion rates of exhibitions in clicks and clicks in acquisitions. According to one of the co-founders of Alpha “… if on 500 users which have clicked there are ten of them who bought, this element gives us information on the rela- tionship between cost-per-click and cost-per-acquisition which is vital to the relationship with the advertiser… performance is not so easily measurable as described in this example …”. The fact that the commission on re- quest (through systems SE) generates by definition higher conversion rates does not mean that the commu- nication is higher than that achieved with traditional me- dia. Indeed, the conversion rate of contacts in return in terms of sales “depends on factors such as timing and brand image, even and especially through other means”. The leaders of Alpha confirm the perception that the traditional ways and forms of online advertising are often complementary in nature, and as such it is appropriate to analyse not as an alternative, but as an integrated effort. If the product and brand doesn’t mature through com- munication that produces awareness, even the possibility of converting leads into sales appears conditioning. The weight of the media and traditional models of communi- cation don’t lose importance as the techniques tradition- ally used in communication such as marketing color, attention to the intercultural dimension in communica- tion through a global potential. 3. The Profile of the New Advertising Agency Integrated in the New Media Market The level of success of an advertising campaign in the on-line context is an issue which was the subject of much attention from academics and operatives, even with ref- erence to specific issues such as brand tracking [31]. Not surprisingly, some authors detect a strong interest from advertising agencies facing the possibility of judging the effects of marketing and metric marketing for Internet advertising [32], especially in some countries [33], as emerges from research about the opportunities to identify how client marketers are evaluating its effectiveness [34,35]. The rise of importance of marketing metrics and accounting has also been observed by other authors [36] and of course is apparent in the new media, since in this context the actors of the on-line media market research opportunities related to identifying how advertisers are evaluating the effectiveness of Internet advertising per- formance of their website and what perceptions are asso- ciated with those components of their communication [37,38,39]7. The pricing of advertising on the Internet includes tra- ditional forms of measurement such as those related to subjective measurements applied to advertisers, with any adjustments relating to various factors (for example, the season). In addition to these traditional forms, this meas- urement may be the result of mathematical formulas re- lated to the measurement of effectiveness. More pre- cisely we can recognize three pricing models and meas- urements that are commonly used to buy and sell “ban- ner advertising”, and which include: 1) costs based on exposure to thousands of users (exposure-based cost-per-thousand); 2) costs for each click that demon- strate forms of interaction (interaction-based click-thr- ough rate); 3) pricing models based on results (out- come-based pricing model) where advertisers pay for measurable elements as requests or purchases [34]. 7In this area, for example, a study designed to identify factors which were capable of supporting websites success has identified that a good candidate was interactivit y [ 30 ] . The definition of pricing per thousands of exposures is Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  SIMONE GUERCINI 123 considered by many advertisers as a formula with a high degree of verifiability compared to others [40,41]. Using that pricing model seems to be based on three considera- tions. Firstly it may miss measures and uniform stan- dards of control based on the results in terms of conver- sion rates. Secondly, the cost-per-thousand model (basi- cally cost per click - Cpc) can be directly compared with the standard practice in more traditional media (particu- larly the print media). Finally, to charge on the basis of costs is consistent with the traditional responsibilities of the publisher to deliver to the advertiser an opportunity to be visible [34,41]. This is the area where advertising agencies are in- volved, which has already been examined in the litera- ture on the basis of the experience of advertising agen- cies in important countries [36]. But this topic is only partially explored. The communication agencies in the on-line media market tend to favour a pricing based solely on objective measures or clicking choices dis- played. In particular, the search engine optimizers are geared to develop communication of the performance metrics on the Internet. Already research carried out some years ago [42] showed that advertising agencies operating on the Internet in the 86% of cases declared using conversion rates to measure the effectiveness of the advertising and only 50% declared using criteria based on a cost-per-thousand exposure or, with different terminology, cost-per-impression [36]. Advertising on the Internet has its own evolution which starts almost immediately with the advent of the network and which is marked by a change of logic un- derlying the possible pricing models for the advertiser. In the second half of the nineties the Internet business is essentially the offer of access to the network (Internet service provider) and advertising on the network is simi- lar to a billboard road, which looks like material inserted in the sites of various actors, including at that time those of search engines [43]. In the next five years (2000-2005) the number of accesses to the Internet had grown enor- mously and businesses operating on the Internet ceased to obtain a fee for the service network access, and in many cases based their revenues on compensation for supplying advertising space. From this moment a process of consideration of advertising defined in terms of cost per impression (Cpim) becomes increasingly weaker. This is a form of remuneration agreement whereby every thousand “passers” by to the site determines the payment of a fee by the poster. To detect the number of steps which are present at this stage essentially two detection systems that also match more generally two types of other media advertising. The first collection system cor- responds to the system “by census” put in place by the same publishers. The second system provides for the evaluation of the audience by third parties, making use of detection systems based on panels, such as those put in place by operators as AC Nielsen. These are systems that, in the opinion of the managers interviewed in the sector, give rise to significant errors that are dependent on the form and the very structure of the panel. Both systems, those “by census” as well as those based on surveys by the panel of third parties are still oriented to “count” the number of “eyes that see advertising”. Beginning in 2005 the advent of new technologies and the flux of new capi- tal lead to a new phase of development of businesses based on the Internet [44,45]. These new technologies are behind the advent of a se- ries of products and platforms that make possible the reformulation of the new business model of online communication. Starting from this moment the commu- nication process carried out in this context tends to differ from what is the traditional world of advertising. This is a step that business operators consider very important. In the first place by traditional forms of evaluation of the consideration of advertising. Cost per impression of Cpim, it moves a more advanced type of cost per click (Cpc), and finally to cost per acquisition (Cpa). These fee formulas for advertising that have no equivalents in advertising built on traditional media such as print media and television. These formulas are possible only for communication on the Internet, in relation to the poten- tial application of related technology. This development makes a decisive contribution to individuality and char- acter specific advertising carried out on online media. The cost of advertising is then connected not only to the relationship between media and audience, in other words it is not simply related to the extension of public exposure to the message because it si reached by means of communication. In the new models the cost of adver- tising is linked more directly to the number of players who are not only exposed, but at least choose to learn more about the object advertised (Cpc), or who buy (Cpa). This step is made possible by technology, but also from the evaluation on a statistical basis of the relation- ship between levels of the purchasing process conducted on-line (conversion rates). In the case of Cpa advertising changes the nature and the cost of communication. Ad- vertising can then be evaluated in direct relation to the margin of the single sale. The extension of advertising for Cpa remains limited, while it is more extensive on Cpc, where most of the advertising proposal lies, such as the leading search engine Google. The process of evaluating the benefit of advertising, which is inevitably linked to evaluating the cost related to it, we are freed from testing the number of “views”, or in other words from its “estimated” audience. The ability to connect to the purchase advertising formula allows the publisher to ask for a share directly for the purchase and not just for the exposition and view. The advertising on Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  SIMONE GUERCINI 124 the Internet in this way tends to be welded directly to the achievement of the sale. The publisher is not only seller the means of communication, but in a sense a direct seller of products, asking for a commission for the sale (Cpa) and not only for the view of the information be- hind the banner (Cpc) or just passing by the site (Cpim). This “short-cut” between communication activities and sales activities has consequences on the publishers’ policies and perspectives. Visitors passing by is no longer sufficient, but we must improve the capability of communication to transform that passage into clicks (which assumes direct importance in the Cpc system) and then in sales (which assumes direct importance in the Cpa system). In other words, the communication process follows the purchase process in its virtual aspect, linking the cost of advertising for the advertiser to the different parameters forming part of the second and third steps of the evaluated process of online purchasing (view, information, purchase). A chain of the steps in the pur- chasing process is therefore reconstructible and a "pipe- line" of online communication, where the advertiser can pay different elements of the process, to transform the de facto editor in a sales player which is recognised a Cpa commission in the system. This sequence of alternatives is the subject of the representation in Figure 3. The advent of “pay per click” makes significant changes in on-line advertising, both in the communica- tion characteristics and policies of the publisher, but also to the very nature of the entity providing work space for advertisers. To be honest this process is not immediate in the sense that different actors in the chain may be di- rected to different levels of the process of informa- tion-evaluation-choice-purchase by the consumer. This process allows the advertiser to connect a cost incurred, with payment for communication, not generic indicators of “visibility” (or “impression”), but directly to the result in terms of sales. Not only that, but this result can be measured in terms of statistical estimation, based on the historical series conversion from impression to click and from click to acquisition, but also directly through the counting of “complete chains” in the path impres- sion-click-acquisition actually made, and to make this ex-ante estimate the impact of online communication on sales. This context there is movement toward at seeking an optimization of online communication (by Seo already Figure 3. The process of switching between different cost configurations for the on-line advertising mentioned in previous sections). Players of this type (as the described case Alpha) operate in a context that pre- sents considerable specificity. The traditional advertising agencies are linked to tra- ditional media, which represent the “technology” dimen- sion around which their production processes have shaped as well as their activities connecting with their current and potential customers. These media have an important role in generating awareness of products, and in general were not able to directly link their contribution to the benefits of sale. The advent of new media, with their new potential, may instead make it possible to con- nect the communication process directly to the sales of the product, bringing the cost of communication to take a different value in both terms of accounting and economic management. Indeed, the cost of advertising can be linked in this case directly to sales that derive from it, and that are specifically measurable in the case of the cost-per-acquisition solution (specific and direct costs). Advertising on the Internet passes so that investment recoverable over time, assumes the characteristics of direct costs related to the online sales process. This point leads to questions about the nature of the communication process and the kind of advertising gen- erated by search engines, as there is no doubt that these are processes that still fall within the field of marketing communications. Therefore the production of communi- cation and advertising in the on-line media market re- quires economic and business evaluations and manage- ment of a different nature from those made in the tradi- tional media market. Enabling concrete potential related to new communication technologies requires a presidium of knowledge, which may be realized using the advice of specialist, which are in the case of search systems the specialized actors already analysed. These consultants assume a contiguous position or play a role which can be even mixed with that of the traditional communications agency. In this context, integration of consultancy and agency communication follows an opposite path that traditional agencies follow in other instances. While the agencies of communication based on the traditional me- dia can experience a tendency to shift from “producers” of advertising and communication to “consultants” for client companies for advertising and communications, the new agencies of the on-line media market can start from consultancy for the optimization of on-line visibil- ity to later take the profile of communication agency that integrates additional competencies. We have seen how the evolving technologies leading to a change in the nature of the communication process and a change of the actors which provide advertising for the on-line media. Change also affects the competitive processes that are generated in the advertising market and the dynamics affecting actors operating in the value Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  SIMONE GUERCINI 125 chain of advertising. Those who are able to offer Cpa communication conditions has a product in itself supe- rior in terms of advertising sales compared to other tradi- tional forms, putting the new media (Internet and search engines specifically) in positions of superiority and ad- vantage, at least in terms of connection with their sales activities, compared to the means of traditional mass communication (first of all print media and television). In terms of actors operating in the value chain of adver- tising, there are two factors that influence and determine a significant change. A first factor relates to the need for a new type of technical skills and expertise, which tradi- tionally were absent from the advertising agency [46], which offer this new type of communication according to the new logic above described. A second factor is related to the presence of actors willing to work on terms of re- muneration (pay-cost) of a different nature, which opens the space to new brokers who are, based on appropriate evaluations, among the various levels, as “converting” to solutions expressed in terms of cost per contact in solu- tions expressed in terms of cost per acquisition. The new forms of communications determine for the advertiser an advertising cost of a different nature than that understood in the traditional sense. The communica- tion budget assigned to traditional media represents a risk because the investor can not assess with certainty the returns related to the cost incurred. This situation will occur even if the investment in online communication falls under the model Cpim. In other words, the investor can buy on-line advertising in the some way as buying advertising on other media, by simply acquiring visual space on the Internet to which the public accesses the media. Changes arriving with the advent of the Cpc model and especially of the Cpa model, also called “cost of acquisition” (Coa). In the latter case, the cost of the online communication takes a different nature as it can be conceived as a “direct cost”, and even as a “specific cost” to the single acquisition. In this case, the commu- nication budget is no longer limited by the decisions on expenditure by the advertiser, but by how much on-line traffic is available and existing since the sale will finance the cost of listing. In this process, the role of the advertising agency is changing in several respects. In the first place it assumes a characteristic of the “communication consultant”, with the same frequency as in the context of the agencies that operate on relatively more traditional media (newspapers, television, billboards, etc.). In the second place it is the customer who changes to a different logic from the past and requires the agency to make a contribution of dif- ferent nature, in some respects a hybrid role between communication and sales8. It is estimated then the concept of click-to-rate (Ctr), or how many clicks it takes to produce a sale (for exam- ple, a Ctr 1% will mean that a sale occurs every one hundred clicks). This sale will depend on the various steps that are in the purchasing process, from the first click produced through the effectiveness of sales promo- tional sense, and to the generation of the final payment (for example through credit card). 4. Some Final Remarks The interrelationship between online media and market- ing communications is a topic of growing interest and importance. The complexity of this issue is due to vari- ous factors which include: 1) current trends in the tradi- tional advertising agency; 2) the emergence of new ac- tors involved in giving support and advice to those who wish to communicate on-line; 3) the integration between traditional advertising agencies and new actors and new technologies relevant to online communication. In this sense on the one hand the trends of the traditional adver- tising agency lead it from a role of producer of advertis- ing to a role of provider of resources and consultancy for the client involved in the communication business [47]. The new players in relation to the new media, such as agencies for communication on the Internet, can in- creasingly provide activities of different types, alongside with solutions similar to those of traditional agencies and related site design and the formulation of elements of on-line visibility. These may be related to the develop- ment of a technological base to specific communications companies involved, rather than on issues of communi- cation in terms of exposure in the new media, integrating with visibility systems of the site in relation to ranking offered by search engines. The new communication agencies taken into consideration in this article are pro- posed as communication optimizers through search en- gines (search engine optimizer - Seo). The specific tech- nical culture in this type of player makes significant un- derstanding of the complexity of the third factor above proposed, which presents a more general value, and that concerns the integration of new and traditional actors in the field of advertising services and communication [48]. As highlighted by Lace [36] the debate on the media, and especially on integration of new media with tradi- tional media, has been largely confined to matters of design and interface with the consumer or generalisa- tions on the need for synergies [49]. The difficulty of traditional advertising agencies to follow the new context of communication [50,51] not only interests technical sophistication related to the inference mechanisms of the functioning of search engines, but is also important on 8In the same manufacturing enterprises in countries with higher adver- tising income, from activities “outsourced” to agencies experts, be- comes in some cases “core business” company. In this area, however the company does not have all the technical skills, and certainly not have the same ability to purchase media, for which the agency main- tains a role as adviser and intermediar y for the means. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  SIMONE GUERCINI 126 the relatively more traditional front of design and online visualizing graphics [36]. The new online agency can operate, as we have seen, on a ground which is in some respects beyond the scope of communication and engages the issue of the sale. To understand the role of this agency it is important to enter the chain of its activities and see what skills and profiles are required. For a long time the traditional advertising agency has specialized professionals such as those present in the creative department in which there are both specialist in computer images and graphics (visualizer) and special- ists of texts (copywriter). There is also the company's interface with customers (accounts), essential for the acquisition and management of budget, and the interface with the means of communication (purchase vehicles). In the case of a new actor in the online communication structure, skills develop in different directions dictated by the characteristics of the media and business models of communication just described. Some authors have shown in past years the develop- ment of skills in the area of new media as a process to be implemented urgently by advertising agencies, since these have had to respond to communication needs of customers even on this front [51]. A significant number of advertising agencies were not, from these studies, proactive in relation to the theme of skills required for this purpose and were not in a position to offer advice and design as part of their services for customers inter- ested in communicating through the emerging media. On the other hand, again from this work it is shown that the Internet can be perceived as a key element of agency services [52], but the development of these activities may be seen as not integrated in their structure9. The organizational profiles required by enterprises in the online media market often provide figures that are at the same time sensitive to issues of communication and marketing and “network fans … with analytical capabili- ties related to the use of mathematics and modelling… but also creative…”10. These figures must develop, next to familiarity with the tool, even a semantics attitude, given the importance of the size of the signs and mean- ings of words. Indeed research on the Internet occurs primarily through “queries” made by network users through “keywords” that become a real product. Those who should interpret them to streamline processes must refine attitude to understanding news reports, an ability to immerse, to reproduce and sensing mechanisms of navigators to improve conversion rates by improving conversion rates in contacts and sales (Ctr or check-to-rate) which has already been referred to a key resource of an agency that has to earn for the customer and itself on the optimization process of conversion is the expansion of the database of keywords and its con- tinuous updating. The commercial or account figure assumes in these companies a growing importance. This is a figure that is to accompany the advertiser in the network, taking on a key role in communication between client and internal staff. This brings the online communication agency to seek integration into its organization of professionals who have matured sales capabilities with potential cli- ents. Assume then importance the complementarity with the resources of more traditional communication agency, which can continue to play for their clients a role as con- tact person in privileged communication processes over- all, by developing a capacity for management of new forms of communication through growth processes (in- ternal or external) in the on-line media market. REFERENCES [1] H. Leighton and J. Srivastava, “First 20 precision among world wide web search services (search engine),” Journal of American Society for Information Science, Vol. 50, No. 10, pp. 870-881, 1999. [2] D. Sabbagh, “Google shows ITV a vision of the future,” The Times, UK Business, pp. 43, Tuesday October 30, 2007. [3] T. Calishan and R. Donfest, “Google hacks,” Second Edition, O’Reilly & Associates, 2004. [4] C. Guo, “A review on consumer external search: Amount and determinants,” Journal of Business and Psychology, Vol. 15, Spring, pp. 505-519, 2001. [5] G. Stigler, “The economics of information,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 69, pp. 213-225, January/Feb- ruary 1961. [6] P. J. Nelson, “Information and consumer behavior,” Jour- nal of Political Economy, Vol. 78, No. 2, pp. 311-329, 1970. [7] R. W. Olshavsky, “Task complexity and contingent processing in decision making: A replication and exten- sion,” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, Vol. 24, pp. 300-316, December 1979. [8] S. Kulviwat, C. Guo, and N. Engchanil, “Determinants of on line information search: A critical review and assess- ment,” Internet Research, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 245-253, 2004. 9In contrast with these studies, other authors have found that advertising agencies were sensitive to the problem and were undertaken to assess the issues and marketing activities related to the Internet [48]. 10Considerations made by a manager and co-founder of a major Italian Internet-based company. [9] P. Wright, “Consumer choice strategies: Simplifying vs optimizing,” Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 11, pp. 60-67, 1975. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  SIMONE GUERCINI 127 [10] N. Srinivasan, “Pre-purchase external search for informa- tion,” in Zeithaml V.E (editor) Review of marketing, American Marketing Association, Chicago, IL, pp. 153- 189, 1990. [11] D. Goh and R. Ang, “Are pay for performance search engines relevant?” Journal of Information Science, Vol. 28, No. 5, pp. 349-355, 2002. [12] Google, AdSense Contextual Advertising Programme, 2005, http://www.google.com/ads. [13] M. P. Evans, “Analysing Google ranking through search engine optimization data,” Internet Research, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 21-37, 2007. [14] Nielsen-NetRatings, Nielsen NetRatings Search Engine Ratings, provided to SearchEngineWatch, July, 2005, http://searchenginewatch.com/reports. [15] E. Burns, “U.S. search core rankings,” Search Engine Watch, 21 March 2008, http://searchenginewatch.com. [16] B. J. Jensen and A. Spink, “How are we searching the world wide web? A comparison of nine search engine transaction logs,” Information Processing and Manage- ment, No. 42, pp. 248-263, 2006. [17] G. Pringle, L. Allison, and D. L. Dowe, “What is a tall poppy among web pages?” Proceedings of the 7th Inter- antional World Wide Web Conference, Brisbane, pp. 369-377, April 1998, http://www.csse.monash.edu.au/~lloyd/tilde [18] S. Fortunato, M. Bocuna, A. Flamini, and F. Menczer, “How to make the top ten: Approximating PageRank from In-degree,” paper presented at the 14th International World Wide Conference, Edinburgh, May 22-26, 2006, http://www.lanl.gov/PS_cache/cs. [19] A. Bifet, C. Castillo, P.-A. Chirita, and I. Weber, “An analysis of factors used in search engine ranking,” Pro- ceedings of the Workshop on Adversarial IR on the Web, Chiba, May 10-14, 2005. [20] C. Boggs, “Seo standards signal the maturity of our in- dustry,” Search Engine Watch, April 4, 2008, http://searchenginewatch.com [21] S. Brin and L. Page, “The anatomy of a large-scale hy- pertextual Web search engine,” Computer Networks, Vol. 30, No. 1-7, pp. 107-117, 1998. [22] F. Rimbach, M. Dannenberg, and U. Bleimann, “Page ranking and topic-sensitive page ranking: Micro-changes and macro-impact,” Internet Research, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 38-48, 2007. [23] SeoBook, SEO for Firefox Tool, 2006, http://tools.seobook.com/firefox/seo-for-firefox.html [24] D. A. Aaker, V. Kumar, and S. George, “Day 2001,” Marketing Research. [25] R. Henshaw, “What next for Internet journals? Implica- tion of the trend toward paid placement in search en- gines,” First Monday, Vol. 6, No. 9, http://firstmonday.org/issues. [26] V. Packard, “The hidden persuaders,” David McKay Company, New York, 1957. [27] K.-H. Rau, “Transformation from Internet portal to the world’s largest Internet communications enterprise,” Internet Research, Vol. 17, No. 4, pp. 435-456, 2007. [28] I. Snehota, “Perspectives and theories of market,” in H. Håkanson, A. Waluszezski, D. Harrison (eds) Rethinking Marketing, John Wiley & Sons, Chinchester, 2004. [29] U. Collesei, F. Casarin, and T. Vescovi, “Disintermedi- azione e reintermediazione nel commercio elettronico,” Convegno Aidea, ottobre, 1999. [30] B. V. Pallas Athena, “FLOWer (2005),” FileNet Corpo- ration, http://www.pallas.nl/. [31] T. Goodwin, “Measuring the effectiveness of on line marketing,” Journal of the Market Research Society, Vol. 4, pp. 403-406, 1999. [32] G. W. Mullarkey, “Internet measurement data – practical and technical issues,” Marketing Intelligence & Planning, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 42-58, 2004. [33] T. Ambler, “Marketing metrics,” Business Strategy Re- view, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 59-66, 2000. [34] R. C. T. Cheung, “Case study of a successful Internet advertising strategy in Hong Kong: A portal for teenag- ers,” Marketing Intelligence & Planning, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 393-405, 2006. [35] M.-C. Boudreau and R. T. Watson, “Internet advertising strategy alignment,” Internet Research, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 23-37, 2006. [36] J. M. Lace, “At the crossroads of marketing communica- tions and the Internet: experiences of UK advertisers,” Internet Research, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp.236-244, 2004. [37] E. T. Bradlow and D. C. Schmittlein, “The little engines that could: Modeling the performance of world wide web search engines,” Marketing Science, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 43-62, 2000. [38] R. Briggs and N. Hollis, “Advertising on the web: Is there response before click-through?” Journal of Adver- tising Research, Vol. 37, pp. 33-45, 1997. [39] Y. Yuan, J. P. Caulkins, and Roehrig, “The relationship between advertising and content provision on the Inter- net,” European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 32, No. 7/8, pp. 677-687, 1998. [40] D. L. Hoffman and T. P. Novak, “Advertising pricing models for the world web,” in D. Hurley, B. Kahin, H. Varian (editors) Internet publishing and beyond, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 45-61, 2000. [41] R. Zeff and B. Aronson, “Advertising on the Internet,” Wiley, New York, NY, 1999. [42] F. Shen, “Banner advertisement pricing, measurement and pretesting practices: Perspectives from interactive agencies,” Journal of Advertising, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 59-67, 2002. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  SIMONE GUERCINI Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM 128 [43] R. H. Ducoffe, “Advertising value and advertising on the web,” Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 36, pp. 21- 35, 1996. [44] S. J. Berman, S. Abraham, B. Battino, L. Shipnuck, and A. Neus, “New business models for the new media world,” Strategy & Leadership, Vol. 35, No. 4, pp. 23-30, 2007. [45] M. Sansone, “Modelli emergenti di interazione tra im- prese e consumatori nell’era digitale: il caso Second Life (Emerging models of firms-consumers interaction in the digital era),” VII Congresso Internazionale Marketing Trends, Venezia 17-19 gennaio, 2008. [46] D. Ogilvy, “Confessions on advertising man,” Atheneum, London, 1963. [47] M. Bonferroni, “La pubblicità diventa comunicazione? (Does advertising evolve in communication?),” Franco Angeli, Milano, 2004. [48] A. J. Bush and V. D. Bush, “Potential challenges the Internet brings to the agency-advertiser relationship,” Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 40, No. 4, pp. 7-16, 2000. [49] R. McLuhan, “Ways to make the clicks measure up,” Marketing, pp. 35, June 2000. [50] G. Baltas, “Determinants of Internet advertising effec- tiveness: An empirical study,” International Journal of Market Research, Vol. 45, No. 4, pp. 490-505, 2003. [51] M. Durkin and M. A. Lawlor, “The implications of the Internet on the advertising agency-client relationship,” The Service Industries Journal, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 175- 190, 2001. [52] T. Bond, “Agencies must adapt to clients’ on line de- mands,” Marketing, pp. 28, December 7, 2000. |