Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

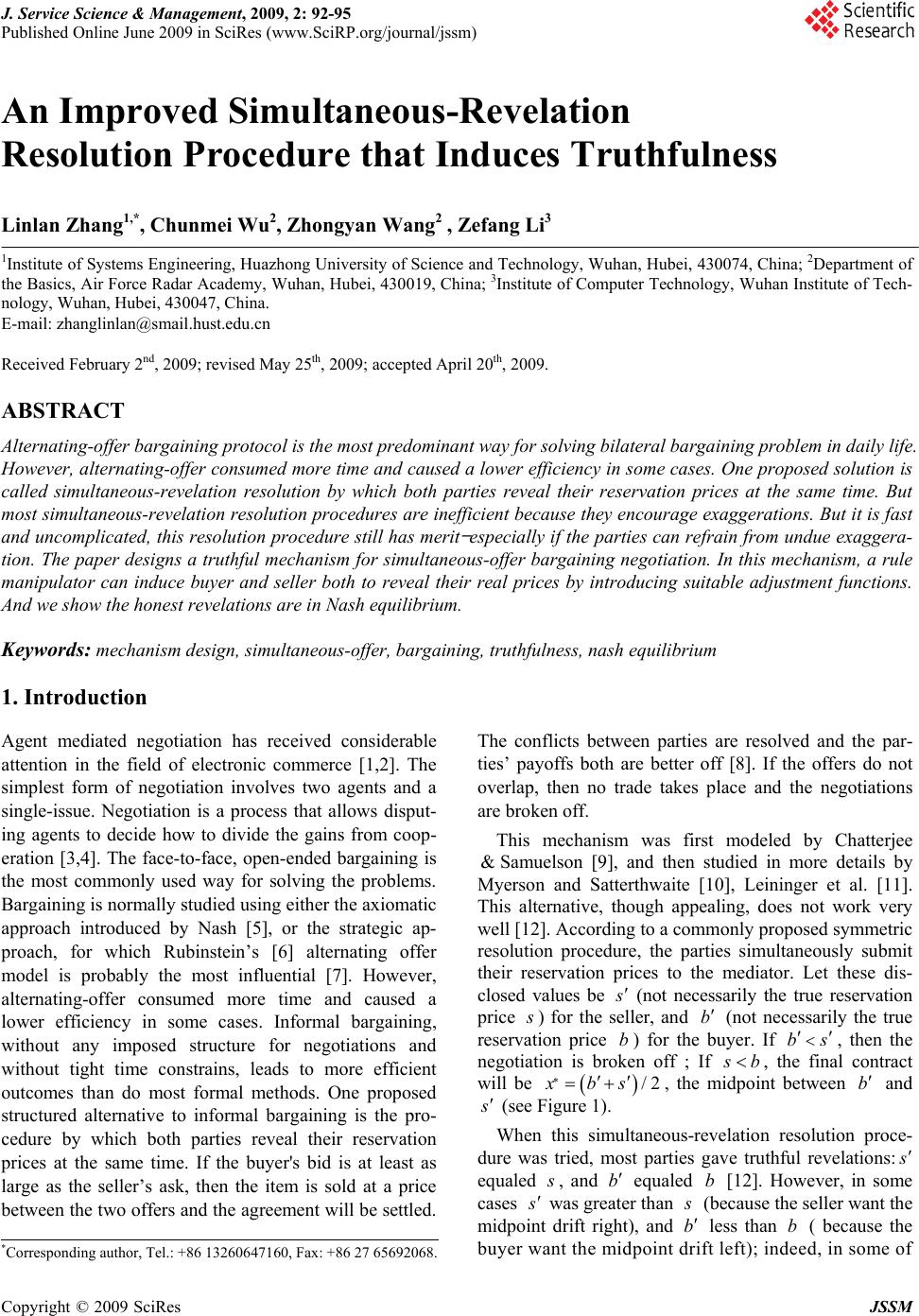

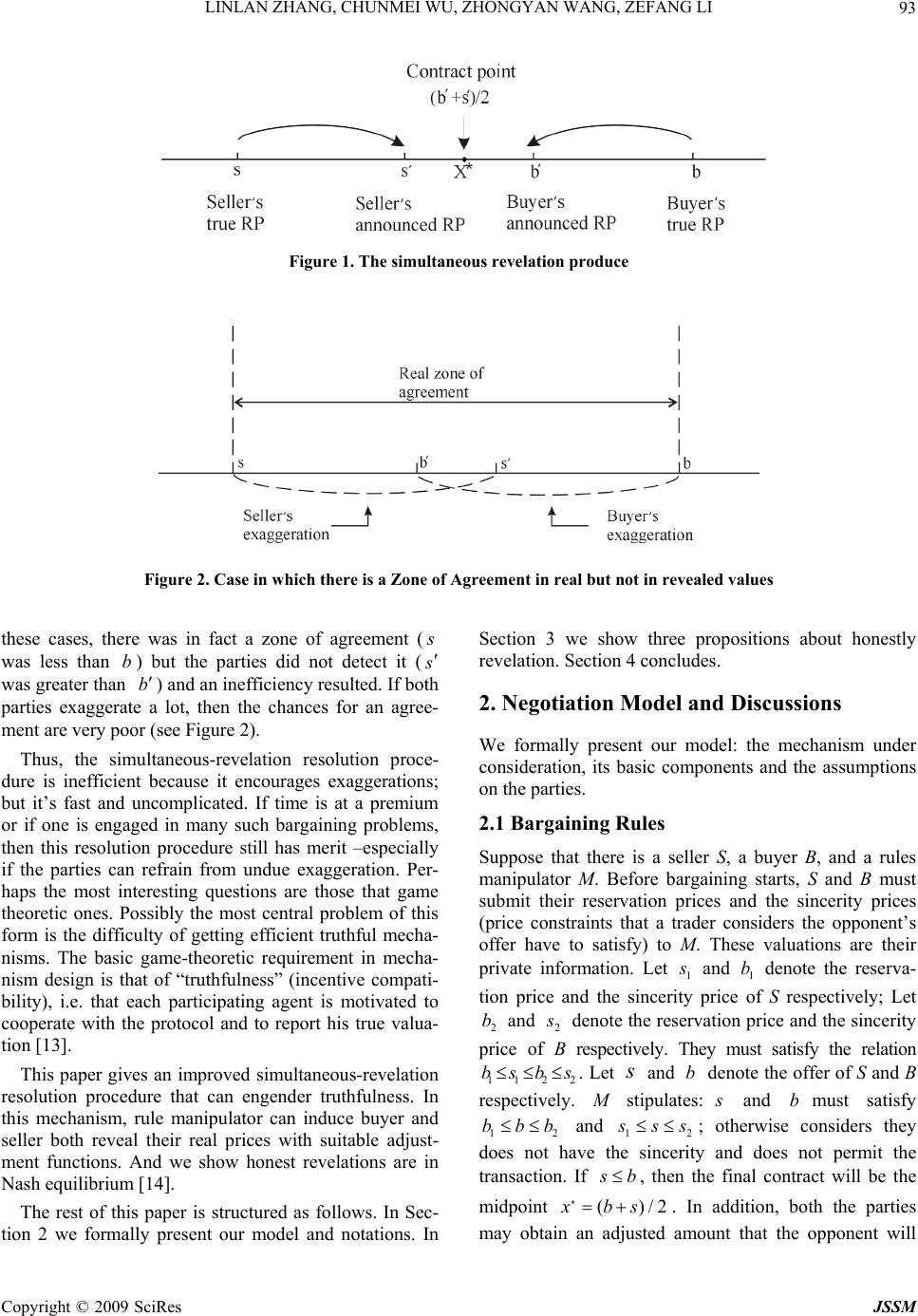

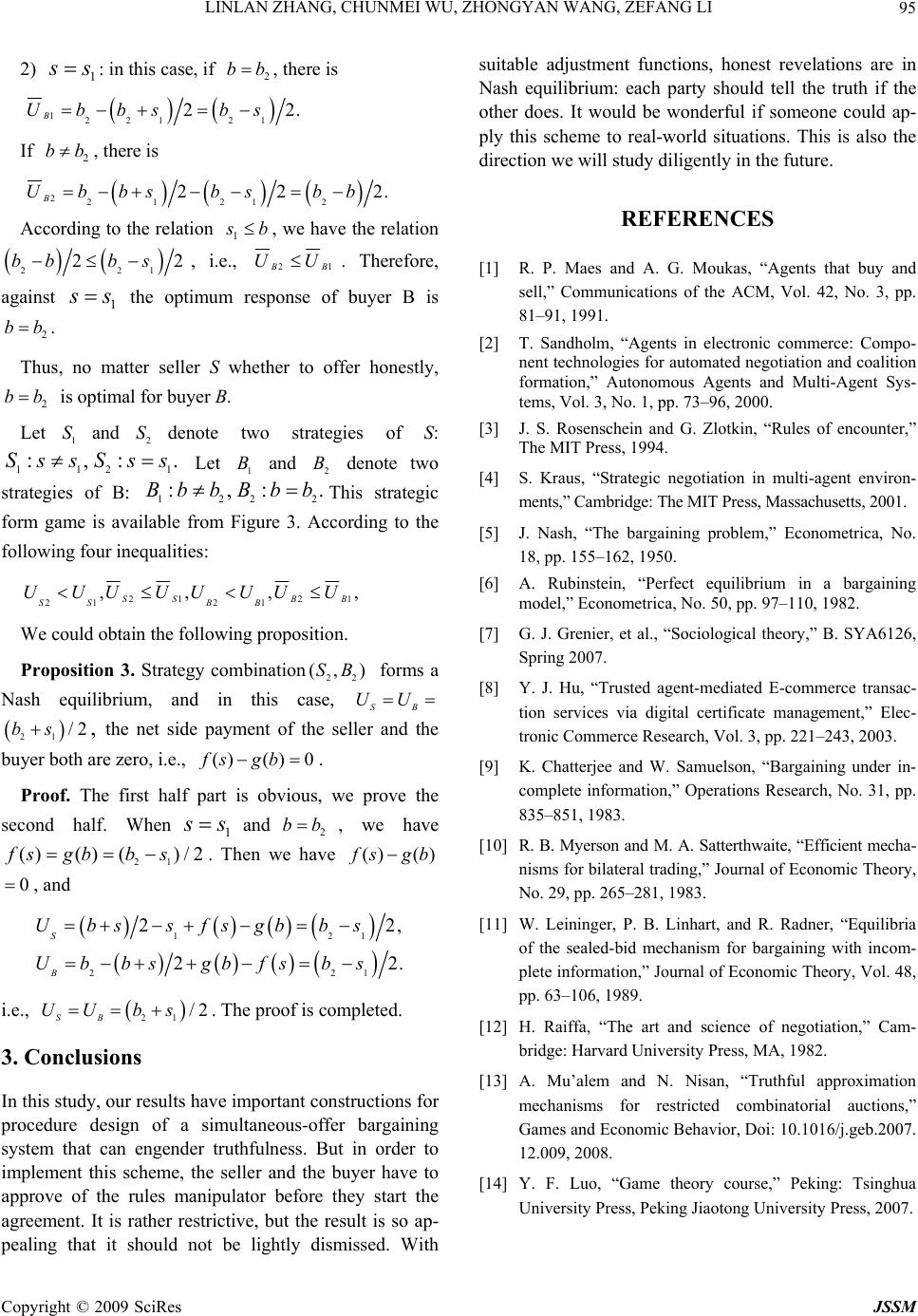

J. Service Science & Management, 2009, 2: 92-95 Published Online June 2009 in SciRes (www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM An Improved Simultaneous-Revelation Resolution Procedure that Induces Truthfulness Linlan Zhang1,*, Chunmei Wu2, Zhongyan Wang2 , Zefang Li3 1Institute of Systems Engineering, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, 430074, China; 2Department of the Basics, Air Force Radar Academy, Wuhan, Hubei, 430019, China; 3Institute of Computer Technology, Wuhan Institute of Tech- nology, Wuhan, Hubei, 430047, China. E-mail: zhanglinlan@smail.hust.edu.cn Received February 2nd, 2009; revised May 25th, 2009; accepted April 20th, 2009. ABSTRACT Alternating-offer bargaining protocol is the most predominant way for solving bilateral bargaining problem in daily life. However, alternating-offer consumed more time and caused a lower efficiency in some cases. One proposed solution is called simultaneous-revelation resolution by which both parties reveal their reservation prices at the same time. But most simultaneous-revelation resolution procedures are inefficient because they encourage exaggerations. But it is fast and uncomplicated, this resolution procedure still has merit — especially if the parties can refrain from undue exaggera- tion. The paper designs a truthful mechanism for simultaneous-offer bargaining negotiation. In this mechanism, a rule manipulator can induce buyer and seller both to reveal their real prices by introducing suitable adjustment functions. And we show the honest revelations are in Nash equilibrium. Keywords: mechanism design, simultaneous-offer, bargaining, truthfulness, nash equilibrium 1. Introduction Agent mediated negotiation has received considerable attention in the field of electronic commerce [1,2]. The simplest form of negotiation involves two agents and a single-issue. Negotiation is a process that allows disput- ing agents to decide how to divide the gains from coop- eration [3,4]. The face-to-face, open-ended bargaining is the most commonly used way for solving the problems. Bargaining is normally studied using either the axiomatic approach introduced by Nash [5], or the strategic ap- proach, for which Rubinstein’s [6] alternating offer model is probably the most influential [7]. However, alternating-offer consumed more time and caused a lower efficiency in some cases. Informal bargaining, without any imposed structure for negotiations and without tight time constrains, leads to more efficient outcomes than do most formal methods. One proposed structured alternative to informal bargaining is the pro- cedure by which both parties reveal their reservation prices at the same time. If the buyer's bid is at least as large as the seller’s ask, then the item is sold at a price between the two offers and the agreement will be settled. The conflicts between parties are resolved and the par- ties’ payoffs both are better off [8]. If the offers do not overlap, then no trade takes place and the negotiations are broken off. This mechanism was first modeled by Chatterjee Samuelson [9], and then studied in more details by Myerson and Satterthwaite [10], Leininger et al. [11]. This alternative, though appealing, does not work very well [12]. According to a commonly proposed symmetric resolution procedure, the parties simultaneously submit their reservation prices to the mediator. Let these dis- closed values be & s (not necessarily the true reservation price s ) for the seller, and (not necessarily the true reservation price ) for the buyer. If , then the negotiation is broken off ; If b bbs s b, the final contract will be */2xbs, the midpoint between b and s (see Figure 1). When this simultaneous-revelation resolution proce- dure was tried, most parties gave truthful revelations: s equaled s , and b equaled [12]. However, in some cases b s was greater than s (because the seller want the midpoint drift right), and less than ( because the buyer want the midpoint drift left); indeed, in some of bb *Corres p ondin g autho r , Tel.: +86 13260647160, Fax: +86 27 65692068.  LINLAN ZHANG, CHUNMEI WU, ZHONGYAN WANG, ZEFANG LI 93 Figure 1. The simultaneous revelation produce Figure 2. Case in which there is a Zone of Agreement in real but not in revealed values these cases, there was in fact a zone of agreement ( s was less than ) but the parties did not detect it ( b s was greater than ) and an inefficiency resulted. If both parties exaggerate a lot, then the chances for an agree- ment are very poor (see Figure 2). b Thus, the simultaneous-revelation resolution proce- dure is inefficient because it encourages exaggerations; but it’s fast and uncomplicated. If time is at a premium or if one is engaged in many such bargaining problems, then this resolution procedure still has merit –especially if the parties can refrain from undue exaggeration. Per- haps the most interesting questions are those that game theoretic ones. Possibly the most central problem of this form is the difficulty of getting efficient truthful mecha- nisms. The basic game-theoretic requirement in mecha- nism design is that of “truthfulness” (incentive compati- bility), i.e. that each participating agent is motivated to cooperate with the protocol and to report his true valua- tion [13]. This paper gives an improved simultaneous-revelation resolution procedure that can engender truthfulness. In this mechanism, rule manipulator can induce buyer and seller both reveal their real prices with suitable adjust- ment functions. And we show honest revelations are in Nash equilibrium [14]. The rest of this paper is structured as follows. In Sec- tion 2 we formally present our model and notations. In Section 3 we show three propositions about honestly revelation. Section 4 concludes. 2. Negotiation Model and Discussions We formally present our model: the mechanism under consideration, its basic components and the assumptions on the parties. 2.1 Bargaining Rules Suppose that there is a seller S, a buyer B, and a rules manipulator M. Before bargaining starts, S and B must submit their reservation prices and the sincerity prices (price constraints that a trader considers the opponent’s offer have to satisfy) to M. These valuations are their private information. Let 1 s and denote the reserva- tion price and the sincerity price of S respectively; Let and 1 b 2 b2 s denote the reservation price and the sincerity price of B respectively. They must satisfy the relation 11 2 bs s 2 b . Let and denote the offer of S and B respectively. M stipulates: sb s and must satisfy b 12 bbb and 12 s ss ; otherwise considers they does not have the sincerity and does not permit the transaction. If s b , then the final contract will be the midpoint . In addition, both the parties may obtain an adjusted amount that the opponent will *()/s 2xb Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  LINLAN ZHANG, CHUNMEI WU, ZHONGYAN WANG, ZEFANG LI 94 pay them that depends on the price they announce. If , they can’t get anything from disagreement. bs 2.2 Assumptions It’s important to keep in mind that the parties must agree to the payoff procedure before they begin to bargain. The adjusted amount is extracted according to following ad- justed function respectively. We express the adjusted function of S and B with () f s and () g b respectively as follows: 221 21 1 121 21 2 2, 2 2, 2 bbbsbbss ss fs bs ss 1 2 s sbsbbss bb gb bs bb Notice that the number s is bigger, the function value of () f s is smaller, namely the higher s the lower the adjusted payment S will receive from B. Simi- larly, the number b is smaller, the function value of () g b is smaller, namely the lower the lower the ad- justed payment B will receive from S. Hence, there is less incentive for S to exaggerate and for B to lessen with the adjustment. We will prove the adjusted functions can induce S and B to make honest revelations: b 1 s s,2 bb , and honest revelations are in Nash equilibrium. All this assumes that they are trying to maximize their utility and they both are risk neutral. 2.3 Main Results According to the rule, we know that the utility function of seller S and buyer B respectively is: 1 2 2 2. S B Ubs sfsgb Ubbs gbfs , We could obtain the following proposition. Proposition 1. No matter the buyer whether to offer honestly, 1 s s is optimal for the seller. Proof. Considering the following two cases: 1) : in this case, if 2 bb1 s s , we have 11121 2 221 2Ubs sbsbbs S. If 1 s s, we have 21 12 1121 22 . 1 bssbsss bsbbss bsss bsbbss S U From the relation 12 s sbb , we have 121 0ss bsbbss . Then we have 21 2 2 S Ubsbb s 1 , i.e., 2S UU 1S . Therefore, against the optimum re- sponse of seller S is 2 bb 1 s s . 2) 2 bb : in this case, if 1 s s,we have 1211 21 22 S Ubs sbs . If 1 s s , we have 22121 1 22 S Ubssbsss 2 . According to the relation 2 s b, we have 12ss 21 2bs, i.e., 21S U S U. Therefore, against 2 bb the optimum response of seller S is 1 s s. Thus, no matter buyer B whether to offer honestly, 1 s s is optimal for seller S. Proposition 2. No matter the seller whether to offer honestly, 2 bb is optimal for the buyer. Proof. Considering the following two cases: 1) 1 s s : in this case, if , we have 2 bb 12 221 21 22 2. B Ubbs bs bss If 2 bb , we have 2 22 21 2 2 21 22 . B bbbs bs bs Ub bbss bbbs bsbbss According to the relation 12 s sbb , we have 221 0.bbbsbbss Then we have 22 21 2 B Ubsbss, i.e., 21 B B UU . Thus against 1 s s the optimum response of buyer B is 2 bb . Figure 3. The strategic form game of the buyer and the seller Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  LINLAN ZHANG, CHUNMEI WU, ZHONGYAN WANG, ZEFANG LI Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM 95 2) : in this case, if 1 ss2 bb , there is 1221 21 22 B Ubbsbs . If , there is 2 bb 221 212 22 B Ubbsbsbb 2. According to the relation 1 s b, we have the relation 22 22bb bs 1 , i.e., 21 B B UU. Therefore, against the optimum response of buyer B is . 1 ss 2 bb Thus, no matter seller S whether to offer honestly, is optimal for buyer B. 2 bb Let and denote two strategies of S: Let and denote two strategies of B: This strategic form game is available from Figure 3. According to the following four inequalities: 1 S 11 :,s 2 S 2 :s1 122 :b b . 2 . Ss Ss Bb 1 B :,B 2 B b 21 2 21 21 ,,, SS BB SS BB UUUUUUU U 1 , We could obtain the following proposition. Proposition 3. Strategy combination forms a Nash equilibrium, and in this case, 22 (, )SB SB UU , the net side payment of the seller and the buyer both are zero, i.e., 21 /2bs () ()fs gb0 . Proof. The first half part is obvious, we prove the second half. Whenand , we have . Then we have 1 ss )/2 2 bb 21 ()()(fsgbbs () () f sgb , and 0 12 2 2 1 21 2 22. S B Ubssfsgbbs Ubbsgbfsbs , [11 i.e., . The proof is completed. 21 /2 SB UU bs 3. Conclusions In this study, our results have important constructions for procedure design of a simultaneous-offer bargaining system that can engender truthfulness. But in order to implement this scheme, the seller and the buyer have to approve of the rules manipulator before they start the agreement. It is rather restrictive, but the result is so ap- pealing that it should not be lightly dismissed. With suitable adjustment functions, honest revelations are in Nash equilibrium: each party should tell the truth if the other does. It would be wonderful if someone could ap- ply this scheme to real-world situations. This is also the direction we will study diligently in the future. REFERENCES [1] R. P. Maes and A. G. Moukas, “Agents that buy and sell,” Communications of the ACM, Vol. 42, No. 3, pp. 81–91, 1991. [2] T. Sandholm, “Agents in electronic commerce: Compo- nent technologies for automated negotiation and coalition formation,” Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Sys- tems, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 73–96, 2000. [3] J. S. Rosenschein and G. Zlotkin, “Rules of encounter,” The MIT Press, 1994. [4] S. Kraus, “Strategic negotiation in multi-agent environ- ments,” Cambridge: The MIT Press, Massachusetts, 2001. [5] J. Nash, “The bargaining problem,” Econometrica, No. 18, pp. 155–162, 1950. [6] A. Rubinstein, “Perfect equilibrium in a bargaining model,” Econometrica, No. 50, pp. 97–110, 1982. [7] G. J. Grenier, et al., “Sociological theory,” B. SYA6126, Spring 2007. [8] Y. J. Hu, “Trusted agent-mediated E-commerce transac- tion services via digital certificate management,” Elec- tronic Commerce Research, Vol. 3, pp. 221–243, 2003. [9] K. Chatterjee and W. Samuelson, “Bargaining under in- complete information,” Operations Research, No. 31, pp. 835–851, 1983. [10] R. B. Myerson and M. A. Satterthwaite, “Efficient mecha- nisms for bilateral trading,” Journal of Economic Theory, No. 29, pp. 265–281, 1983. ] W. Leininger, P. B. Linhart, and R. Radner, “Equilibria of the sealed-bid mechanism for bargaining with incom- plete information,” Journal of Economic Theory, Vol. 48, pp. 63–106, 1989. [12] H. Raiffa, “The art and science of negotiation,” Cam- bridge: Harvard University Press, MA, 1982. [13] A. Mu’alem and N. Nisan, “Truthful approximation mechanisms for restricted combinatorial auctions,” Games and Economic Behavior, Doi: 10.1016/j.geb.2007. 12.009, 2008. [14] Y. F. Luo, “Game theory course,” Peking: Tsinghua University Press, Peking Jiaotong University Press, 2007. |