Surgical Science, 2011, 2, 95-101 doi:10.4236/ss.2011.22020 Published Online April 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ss) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. SS A Critical Deficit of OBGYN Surgeons in the U.S by 2030 Bhagwan Satiani, Thomas E Williams, Mark B Landon, E. Christopher Ellison, Steven G Gabbe From the Departments of Surgery & Obstetrics and Gynecology The Ohio State University College of Medicine E-mail: bhagwan.satiani@osumc.edu Received April 9, 2010; revised Febr uary 20, 2011; accepted Marc h 28, 2011 Abstract Objective: To estimate the OB/GYN Surgical workforce needed in the U.S by 2030 to meet the needs of our population. Methods: Using a population based analysis, the net supply of OB/GYNs was calculated. Our assumptions included: a ratio of OB/GYN’s to population of 27.10/100,000 women, practicing 25 years from Board Certification to retirement, 1200 graduates finishing from residency programs per year. Results: To maintain our current ratio per 100,000 population, we should have 50,135 OBGYN’s practicing for a popula- tion of 364 million in 2030. We estimate the supply to be only 30,000 and hence a shortage of 20,135. To rectify the deficit 44,135 residents will require training in OBGYN with the cumulative cost exceeding $14 billion. Conclusions: 1) We estimate a 40% shortage of OB/GYN’s as the best case scenario to meet the needs of the U.S population by 2030 if the current training paradigm stays constant. 2) The cumulative cost of training adequate numbers of OB/GYN’s is estimated at $14 billion and 3) In addition to revising the BBA of 1997 to permit more residents to be trained in the United States, additional strategies must be con- sidered to provide an adequate workforce and ensure patient access to OBGYN’s. Keywords: OBGYN, Surgeons, Shortage 1. Introduction With healthcare reform legislation having passed and coverage for millions of under-insured or uninsured be- ing ensured, policy makers have not considered the ade- quacy of the physician workforce in the U.S as a critical factor in access to healthcare. Some stakeholders, how- ever, are beginning to understand that the shortage of physicians is bona fide and already here. In a 2009 sur- vey by a large clinical staffing company 91% of Hospital Chief Executive Officers (CEO’s) believe there is a shortage of physicians. [1] Residents are now inundated by employment offers early in their training. Residents receiving between 51-100 job offers during their resi- dency jumped from 16% in 1999 to 52% in 2006. [2] The demand for selected specialties has raised starting salaries well above the inflation rate with a cumulative annual growth rate between 6.6% and 10.3% between 2001 and 2006 compared to 2.8% for other professional occupations. [2] Merritt Hawkins reports that searches offering signing bonuses soared from 50% in 2003/2004 to 85% in 2008-2009. [3] Finally, as a sign for politician s, 60% of voters believe there are too few physicians in practice and over two-thirds believe th ere will be too few physicians in the next ten years. [4] There are multiple reasons for the shortage of physi- cians in the U.S including the specialty of Obstetrics and Gynecologists (OBGYNs). The chief cause is continued growth in the U.S population and a static supply of phy- sicians necessitated by a freeze in the funding of the number of training residency positions at 1996 levels through the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. In order to pre-empt critical problems in access to OBGYN care, there is a need to estimate the degree of shortages ahead of us and discuss possible solutions. The objectives of this study therefore were to estimate the OBGYN work- force needed by 2030 to meet population needs, to quan- tify the costs if Congress decides to revise the Balanced Budget Act and to propose possible solutions. 2. Material and Methods. To estimate the number of OBGYN specialists trained each year, we used the number of certificates granted by the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology as published by the American Board of Medical Specialties.  96 B. SATIANI ET AL. [5] Population estimates and the proportion of women in the future was derived from the U.S Census Bureau fig- ures. [6] Assumptions 1) The ratio of 27.1 OBGYNs per 100,000 women will remain the same as it was in 2005. [7] 2) There were 39,024 obstetricians and gynecologists practicing in the United States as in 2005. 3) OBGYNs will practice 25 years from Board Certi- fication to retirement, death or disability with 1,561 re- tiring each year. 4) There will continue to be 1,200 OBGYNs certified each year. 5) The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 will not be re- vised and the number of first year trainees in OBGYN will remain constant. 6) We used Richard Cooper’s figure of $80,000 for direct medical education expenses per resident per year. [8] The total cost consists of a salary of $50,000, benefits of 30% or $15,000, and other direct medical education funds of $15,000 for a total of $80,000. We have elected to use nominal dollars unadjusted for inflation to sim- plify our estimates. 3. Results/Calculations 25 year to retirement 1) To calculate the OBGYNs in practice for the base- line year 2006, we started with 39,024 in practice in the year 2005, subtracted the number of retired OBGYNs (1,561) and added the newly Board Certified practitio- ners (1200). This process was repeated to generate the supply of OBGYNs until 2030. The calculations are il- lustrated in Table 1, and also in Table 2 (fourth col- umn). 2) The OBGYNs needed are calculated by multiplying the population of women projected by the Census Bureau in that year in that year by 27.1 (OBGYNs per 100,000 women) an d di vi ded by 100, 0 00. (Table 2, column 3) 3) The shortage (361 OBGYNs leaving the workforce each year) is calculated by subtracting the OBGYNs needed from those in practice (column 5 in Table II); the shortage percentage is calculated by dividing the short- age by the OBGYNs needed and multiplying by 100. 30 Years to Retirement We use the same assumptions, method and calcula- tions to project the OB/GYN workforce in Table III and column 3 of Table IV. This work is exempt from IRB permission since no patient records or information was used. Cost of Training The cost of direct medical education for OBGYN trainees is shown in Columns 2 and 3 of Table 3. The Table 1. Supply of obgyn’s w i th 25 year s practice span. YEAR PRACTICING NEW TOTAL OBGYN’S OBGYN’S OBGYN’S 2005 39,024 39,024 2006 37,463 1,200 38,663 2007 35,902 2,400 38,302 2008 34,341 3,600 37,941 2009 32,780 4,800 37,580 2010 31,219 6,000 37,219 2011 29,658 7,200 36,858 2028 3,121 27,600 30,721 2029 1,560 28,800 30,360 2030 0 30,000 30,000 2031 0 30,000 30,000 Table 2. Shortage of obgyn’s: 25 years practice span. Projected OBGYN’sOBGYN’s Per Cent YearPopulationNeededin Practice ShortageShortage 2005144,000,00039,024 39,024 2010157,000,00042,547 37,219 5,328 13% 2020171,000,00046,341 33,609 12,732 27% 2030185,000,00050,135 30,000 20,135 40% Table 3. Shortage of obgyn’s: 30 years practice span. Projected OBGYN’sOBGYN’s Per Cent YearPopulationNee dedin Practice ShortageShortage 2005144,000,00039,024 39,024 2010157,000,00042,547 38,519 4,028 9% 2020171,000,00046,341 37,509 8,832 19% 2030185,000,00050,135 36,499 13,636 27% surgeons needed, surgeons in practice, and the shortage as indicated in Column 2 of Table 4 are from the year 2030 in Table 2. The total ESTIMATED TO BE CER- TIFIED-2011 TO 2030 in the 4 th row of Table 4 (24,000 OBGYNs) is obtained by multiplying 1200 (board certi- fied OBGYNs) by twenty years. The shortage was esti- mated at 20,135 and 13,636 OBGYNs for a career span of 25 and 30 years, respectively. We then added the shortage and the estimated to be certified to obtain the TOTAL TO BE TRAINED-2011 TO 2030 (44,135 OBGYNs) in Table 4, Column 2 for 25 years and 37,636 in Column 3 for 30 years. This number Copyright © 2011 SciRes. SS  B. SATIANI ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. SS 97 Table 4. Costs for direct medical education. YEARS TO RETIREMENT 25 YEARS 30 YEARS OBGYN’s NEEDED 50,135 50,135 OBGYN’s IN PRACTICE 30,000 36,499 SHORTAGE 20,135 13,636 ESTIMATED TO BE CERTIFIED-2011 TO 2030 24,000 24,000 TOTAL NEEDED TO BE TRAINED-2011 TO 2030 44,135 37,636 NUMBER PER CLASS 2,207 1,882 TRAINEE YEARS PE R CLASS 8,827 7,527 PER CLASS COST AT $80,000 $706,160,000 $602,176,000 TOTAL COST-2011 TO 2030 $14,123,200,000 $12,043,520,000 Figure 1. The supply of OBGYNs from 2006 (assuming a 25 year career span) as the baseline to 2050 is illustrated by adding new practicing OBGYNs (light grey), attrition of practici ng OBGYNs (blac k) and total supply (medium grey). 4. Discussion was divided by 20 to obtain the class size, NUMBER PER CLASS, for 20 years, more than 2,200 for 25 years and almost 1,900 for 30 years. There have been several workforce studies in the OB- GYN specialty starting with a 1998 actuarial supply model analysis by Jacoby and colleagues. [9] A number of different algorithms or models have been used for estimating physician supply including the Work Per Capita Analysis model [10], the Cooper model [11] and the Physicians Supply Model & Physicians Requirement Model. [12] Our algorithm is a simplified population analysis model because it uses gross numbers by spe- cialty, adds the number of physicians entering the work- force, subtracts those leaving medical practice, and esti- mates the future supply. Yet, our population analysis estimate for the total medical workforce in 2020 of We multiplied these figures by 4 to determine the TRAINEE YEARS PER CLASS–8828 in column 2 and 7,528 in column 3 of Table 4. To calculate per class cost we multiplied the TRAINEE YEARS PER CLASS by $80,000 for the PER CLASS COST AT $80,000. This results in a $706,000,000 cost for 25 years and about $600,000,000 for 30 years. We subsequently multiplied the PER CLASS COST AT $80,000 by 20 to arrive at more than $14 billion and $12 billion for cost estimates of 25 years to retirement and 30 years, respectively (TOTAL COST-2011 TO 2030).  98 B. SATIANI ET AL. 960,960 is consistent with the Health Resources and Ser- vices Administration model of 951,800 and with the Council of Graduate Medical Education (COGME) model, which arrives at physician supply of 971,817. [13,14] In addition, our estimate of a shortage of about 200,000 physicians in 2020 is akin to Cooper’s shortage estimate of about 200,000 physicians. [15] The U.S Census Bureau projects the female population to be 157 million in 2010, 170 million in 2020, and 213 million in 2050. [16] The ratio of OBGYNs per 100,000 women has gradually increased from 23.0 in 1978 to 27.1 in 1997. [7] Our assumption of 27.1 OBGYNs per 100,000, which approximates 39,000 OBGYNs practic- ing in 2000, is consistent with the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology’s actual number of 40,240 OB/GYNs in practice in the year 2000. [17] Assumed board certification of 1,200 residents each year and using 27.1 OBGYN specialists per 100,000 women in 2010 as a baseline, 42,547 OB/GYN specialists will be needed to take care of our women’s’ needs. [17] In 2030, that number will increase to almost 50,135 specialists. Using a 25-year practice horizon, the shortage in the year 2030 is estimated to be 20,135 (40%) OBGYNs. (Table 2) The Balan ced Budget Act (BBA) of 1997 attempted to slow the growth of the physician workforce by freezing the full time equivalent (FTE) resident cap at 1996 levels and created incentives to reduce resident positions in response to a chorus of concerns about physician over supply. Medicare has been the main source of graduate medical education (GME) since its inception in1965. In 2007, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that indirect medical education expenses incurred by Medi- care alone were $5.7 billion and direct medical education costs were $2.8 billion. [18] With large budget deficits and a stratospheric national debt, rather than increasing funding for trainee positions, existin g subsidies are lik ely to face increased scrutiny. Confounding variables Some of the variables influencing the accuracy of this workforce model include: the per-unit work by the phy- sician, the duration of practice and retirement patterns, lifestyle considerations and the increasing sub-speciali- zation of OBGYNs. Although the number of Board Cer- tified OBGYNs pe r 100,000 women h as increased, ab out 20 percent of OBGYNs do not practice obstetrics and stopped doing so at an average age of 48. [19] A signifi- cant error in estimation of workload may also occur if these specialists provide more or less primary or gener- alist care than is generally estimated in most workforce studies. Jacoby and associates observed that of the women Medicare patients seen by an OBGYN, 13% re- ceived more than half of their medical work (as meas- ured by relative value units billed) from their OBGYN. [9] Any change in th is pattern could alter the de mand for OBGYNs. Discussion of per-unit work by sex as a variable is an important consideration. In 2006, women represented 27 percent of active physicians, but 42 percent of all resi- dents/fellows in ACGME accredited programs in the United States. [20] For the years 1997–2004, 73.3 per- cent of residents who chose OBGYN were female in contrast to 21.6 percent and 47 percent who selected sur- gery and primary care, respectively. [19] Pearse et al. used the American Medical Association socio-economic survey to review gender differences in work reported by OBGYNs. More female OBGYNs un- der age 40 reported reducing their hours or stopped their practice completely for extended periods of time for family reasons than men (23% versus 5%). [7] In the survey of 230 ACOG members, female OBGYNs under age 40 reported working 24.7 hours per week in the of- fice compared to 27.5 hours for men. Significant differ- ences in in-patient visits per week (females 10.1 versus males 12.8 per week, p < 0.01) and working > 60 hours per week (females 22.1% versus males 31.5%, p < 0.05) were reported by Benedetti and co-authors. [21] Much has been made about women choosing ‘control- lable’ specialties. In a survey of medical students from 1996–2003, the percentage of women who chose special- ties with controllable lifestyles increased from 18 percent in 1996 to 36 percent in 2003. [2] But, importantly the percentage of men who chose controllable lifestyles grew from 28 percent in 1996 to 45 percent in 2003. [22] There are varying opinions about whether reduced work hours lead to greater career satisfaction in women. [23, 24] Based on the evidence cited generational preferences for a controllable lifestyle may be more of a factor than gender differences today. Early retirements sooner than the 25 or 30-year career span we have used in our estimates will also change the OBGYN future workforce estimates. Early retirements among physicians over the age of 55 are 35.7% in 2007 compared to 27.5% in 1985. [25] The average age of retirement of female physicians is four years sooner than male physicians. [26] Eighty percent of female physi- cians are retired by age 65 compared to only 60% of male physicians. [27] In addition, female OBGYNs also have a higher percentage of physician spouses (46%) compared to male OBGYNs (7%) further explaining their choice of fewer work hours and possibly retiring earlier. [28] If surveys of physician practice plans are an indicator, the shortages may be more severe than our estimates. [29] Another variable is the increasing number of OBGYN Copyright © 2011 SciRes. SS  B. SATIANI ET AL. 99 trainees who choose one of the sub-specialties within OBGYN. Pearse and co-authors in a workforce analysis in 2000 projected that by 2020 Gynecologic Oncology and Maternal Fetal Medicine sub-specialists would dou- ble (460 to 955 and 648 to 1317, respectively) and REI specialists would increase from 605 to 760. [30] In- creasing sub-specialization will have a negative effect on OBGYNs available for delivering babies. Jacoby et al estimated that in 1994 82% of deliveries were performed by OBGYNs and 22% by family and general practitioners. [9] According to a 2008 survey of FP’s by the American College of Family Physicians, about 23% of members reported performing an average of 40 deliveries annually (2003 data). [31] Failing a long-term solution for high professional liability, it is possible that family practitioner’s may abandon deliver- ies further increasing the workload for OBGYNs. 5. Some Solutions Our estimates indicate that additional funding for 1000 additional physicians per year from 2011 to 2020 unad- justed for inflation would amount to about $1.6 billion over a 20-year period or $80 million per year starting in 2011. (Tab le 4) Despite massive budget deficits and un- funded liabilities, we believe this relatively modest in- vestment would partially address the OBGYN shortage. We have previously discussed some solutions for the coming shortage of surgical specialties. [32, 33] How- ever, OBGYN has unique specialty needs in that it has a large and important primary care component. Work hour restrictions also effect care of the OB GYN patient. Fewer work hours translate to about a 20 percent reduction in work effort of the n ation’s medical residents and fellows, which is equivalent to losing the workload of about 15,000 to 22,000 full-time residency positions. [34] In order to compensate for fewer work units per OBGYN physician, part-time employment must be of- fered. The percentage of part-time physicians increased from 13 percent in 2005 to 20 percent in 2007 and more than 80 percent of physicians who practice part time are at least 0.5 FTE. [35] Expectedly, the work force in this category consists mostly of pre-retirement males and early career females. [35] Eighty- four percent of all academic OBGYN departments report part-time faculty, who constitute 21.2% of all OBGYN physicians. [36] A higher percentage of women had part-time jobs com- pared to men (23% versus 16.2%, p = 0.23) Because part-timers wish to avoid the long hours and night call, yet cannot afford to reduce their practices, many are forced to retire prematurely or choose alternative careers. Sixty-nine percent of female physicians and 11% of male physicians who practiced part-time indicate family re- sponsibilities as the reason for cutting back. Until com- prehensive tort reform is enacted, one way for hospitals to take advantage of the older doctors’ experience is to employ them under a hospital liability umbrella program. The advent of the hospitalists as promoted by the In- stitute of Medicine may allow for a controlled lifestyle, less burnout and prolongation of a physician’s career span. It may also lead to more efficient and standardized obstetric practice. The ‘laborist’ model may allow future obstetricians to work part-time, limit their work hours and escape the malpractice premium burden. [37] The average age at retirement of physicians is 63 years. [38] In the 55–65 age group, the percentage of physi- cians planning to retire in the next three years has more than doubled from 9 percent in 2004 to 20 percent in 2007. [2] The brunt of the work will be assumed by OBGYNs in this age group but with the lifestyle choices of this generation, mentoring programs to assist younger physicians, periodic sabbaticals and hospital employment to reduce the added stress of practice management may all be necessary to keep them from dropping out. In business terms, the return on investment for sig- nificant taxpayer and private resources expended into physicians is poor when they either take substantial time off or retire early due to family obligations, illness or burnout. One way to recoup the outlay and add them back into the pool is through so-called ‘re-entry’ pro- grams. The American College of Obstetricians and Gy- necologists Task Force on Reentry is one such initiative that could be expanded. The task force estimates there are several hundred, if not more, OBGYNs who co uld be re-trained through establishment of short refresher pro- grams. [39] A whole host of other actions such as function shifting by training more Physician Assistants and Nurse Practi- tioners, reducing non-clinical duties of OBGYNs, im- proving productivity by electronic medical records, de- creasing regulatory coding and documentation require- ments and possibly shortening training programs are steps that could be taken in conjunction with other ac- tions. Simply cycling more med ical students through our schools and trying to convince Congress to fund addi- tional GME positions with billions in a time of financial crisis without other fundamental changes in our system will likely fail and result in a crisis of access for OBGYN patients used to extraordinary care. Conflict of interest. None of the autho rs have any co n- flicts to disclose. 6. References [1] A. M. N. Healthcare, “2009 Survey of Hospital Chief Executive Officers”, Clinical workforce issues, Copyright © 2011 SciRes. SS  100 B. SATIANI ET AL. http://www.amnhealthcare.com/PDF/09CEOSurvey.pdf. [2] Health Care Advisory Board, “Physician Recruitment: Attracting Talent in a Competitive Market,” Washington, DC: The Advisory Board Company, 2008. http://www.advisory.com/members/default.asp?contentID 73082&collectionID1021&program14&filename73082.x ml. [3] Merritt Hawkins & Associates, “2009 Review of Physi- cian & CRNA Recruiting Incentives,” http://merritthawkins.com/compensation-surveys.aspx. [4] “AAMC 2007 Workforce Charts,” http://www.aamc.org/workforce/, accessed 12/23/2009. [5] http://www.abms.org/News_and_Events/Media_Newsroo m/facts_and_background.aspx, accessed 12/23/2009. [6] http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/usint erimproj/, accessed 12/23/2009. [7] W. H. Pearse, W. H. J. Haffner and Primack A, “Effect of Gender on the Obstetric-Gynecologic Workforce,” Ob- stetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 97, No. 5, 2001, pp. 794-797. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(01)01191-7 [8] R. A. Cooper, “It's Time to Address the Problem of Phy- sician Shortages Graduate Medical Education Is the Key,” Annals of Surgery, Vol. 246, No. 4, 2007, pp. 527-534. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181571bc1 [9] I. Jacoby, G. S. Meyer and W. Haffner, “Modeling the Future Workforce of Obstetrics and Gynecology,” Ob- stetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 92, No. 3, 1998, pp. 450-456. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(98)00185-9 [10] D. Etzioni, J. Liu, M. Maggard and C.Y. Ko, “The Aging Population and Its Impact on the Surgery Workforce,” Annals of Surgery, Vol. 238, No. 2, 2003, pp. 170-176. doi:10.1097/01.SLA.0000081085.98792.3d [11] R. A. Cooper, T. E. Getzen and P. Laud, “Economic Ex- pansion Is a Major Determinant of Physician Supply and Utilization,” Health Services Research, Vol. 38, No. 2, 2003, pp. 675-696. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.00139 [12] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration Bureau of Health Professions, “Physician Supply and Demand: Projections to 2020,” ftp://ftp.hrsa.gov/bhpr/workforce/PhysicianForecastingPa perfinal.pdf. [13] Council On Graduate Medical Education, “Physician Workforce Policy Guidelines for the United States, 2000—2020, January 2005,” Sixteenth Report, https://services.aamc.org/Publications/showfile.cfm?file= version111.pdf&prd_id=229&prv_id=279&pdf_id=111. [14] R. D. Blackwell, T. E. Williams and A. Ayers, “Con- sumer Driven Health Care,” Book Publishing Associates, 2005, pp. 127-130. [15] R. A. Cooper, “Weighing the Evidence for Expanding Physician Supply,” Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 141, No. 9, 2004, pp. 705-714. [16] http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/usint erimproj/, accessed 12/23/2009. [17] American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Resource Center, Manpower Statistics, Courtesy Mary A Hyde, Director. [18] Congressional Budget Office, http://www.cbo.gov/budget/factsheets/2008b/medicare.pd f. [19] R. P. McAlister, D. P. Andriole and S. A. Brotherton, “Are Entering Obstetrics/Gynecology Residents More Similar to the Entering Primary Care or Surgery Resident Workforce?” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gyne- cology, Vol. 197, No. 5, 2007, pp. 5361-5366. [20] Association of Academic Medical Centers, “The Com- plexities of Physician Supply and Demand,” http://services.aamc.org/publications/showfile.cfm?file=v ersion125.pdf&prd_id=244&prv_id=299&pdf_id=125. [21] T. J. Benedetti, L. M. Baldwin and H. A. Andrilla, “The Productivity of Washington State’s Obstetri- cian-Gynecologist Workforce: Does Gender Make a Dif- ference?” Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 103, No. 3, 2004, pp. 499-505. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000113617.94134.fd [22] E. M. Lambert and E. S. Holmboe, “The Relationship Between Specialty Choice and Gender of U.S. Medical Students, 1990-2003,” Academic Medicine, Vol. 80, 2005, pp. 791-796. doi:10.1097/00001888-200509000-00003 [23] K. Keeton, D. E. Fenner, T. R. B. Johnson and R. A. Hayward, “Predictors of physician career satisfaction, work-life balance, and burnout,” Obstetrics and Gyne- cology, Vol. 109, No. 4, 2007, pp. 949-955. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000258299.45979.37 [24] R. L. Kravitz, J. P. Leigh, S. J. Samuels, M. Schembi and W. M. Gilbert, “Tracking Career Satisfaction and Percep- tions of Quality Among US Obstetricians and Gynecolo- gists,” Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 102, No. 3, 2003, pp. 463-470. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(03)00666-5 [25] Association of Academic Medical Centers, “Physician Specialty Data: A Chart Book. Center for Workforce Studies,” 2006, https://services.aamc.org/publications/showfile.cfm?file= version67.pdf&prd_id=160&prv_id=190&pdf_id=67. [26] H. Yamagata, “Retirement Behaviors of Physicians Based Upon the Physicians Over 50 Survey,” Paper pre- sented at the 2006 AAMC physician workforce research conference, 2006. [27] J. E. McMurray, G. Angus, M. Cohen, “Work Hours: Medicine: A Four Nation Comparison,” Journal of the American Medical Women's Association, Vol. 57, No. 4, 2002, pp. 185-190. [28] W. H. Pearse and J. G. Felden, “The Young Obstetri- cian-Gyneco-Logic Academic Faculty Manpower,” Ob- stetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 86, No. 5, 1995, pp. 1018- 1020. doi:10.1016/0029-7844(95)00333-M [29] J. Merritt, J. Hawkins and P. B. Miller, “Will the Last Physician in America Please Turn Off the Lights?” Prac- tice Support Publisher, Vol. 18, 2006. [30] W. H. Pearse, N. F. Gant and A. P. Hagner, “Workforce Projections for Sub Specialists in Obstetrics and Gyne- cology,” Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 95, No. 2, Copyright © 2011 SciRes. SS  B. SATIANI ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. SS 101 2000, pp. 312-314. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(99)00545-1 [31] American Academy of Family Physicians, “Practice Pro- file I Survey,” 2008. [32] T. E. Williams and E. C. Ellison, “Population Analysis Predicts A Future Critical Shortage of General Surgeons Surgery,” Vol. 144, No. 4, 2008, pp. 548-556. [33] T. E. Williams, B. Satiani, A. Thomas and E. C. Christo- pher, “The Impending Shortage and the Estimated Cost of Training the Future Surgical Workforce,” Annals of Sur- gery, Vol. 250, No. 4, 2009, pp. 590-597. [34] A. Salim, P. G. R. Texeira, L. Chan and D. Oncel, “Im- pact of the 80-Hour Workweek on Patient Care at a Level I Trauma Center,” Archives of Surgery, Vol. 142, No. 8, 2007, pp. 708-714. [35] Cejka Search & American Medical Group Association, “2007 physician retention survey,” http://www.cejkasearch.com/media/news/physician-retent ion-survey-2007-pr.htm. [36] W. F. Rayburn, B. L. Anderson, J. V. Johnson, M. A. McReynolds and J Schulkin, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 115, 2010, pp. 141-146. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c3f513 [37] L. Weinstein, “The Laborist: A New Focus of Practice for the Obstetrician,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 188, No. 2, 2003, pp. 310-312. doi:10.1067/mob.2003.133 [38] J. P. Leigh, R. L. Kravitz, M. Schembri, S. J. Samuels and S. Mobley, “Physician Career Satisfaction Across Specialties,” Archives of Internal Medicine, Vol. 14, No. 162, 2002, pp. 1577-1584. doi:10.1001/archinte.162.14.1577 [39] K. E. Adams, R. Allen and J. M. Cain, “Physician Reen- try. A Concept Whose Time Has Come,” Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 111, No. 5, 2008, pp. 1195-1198.

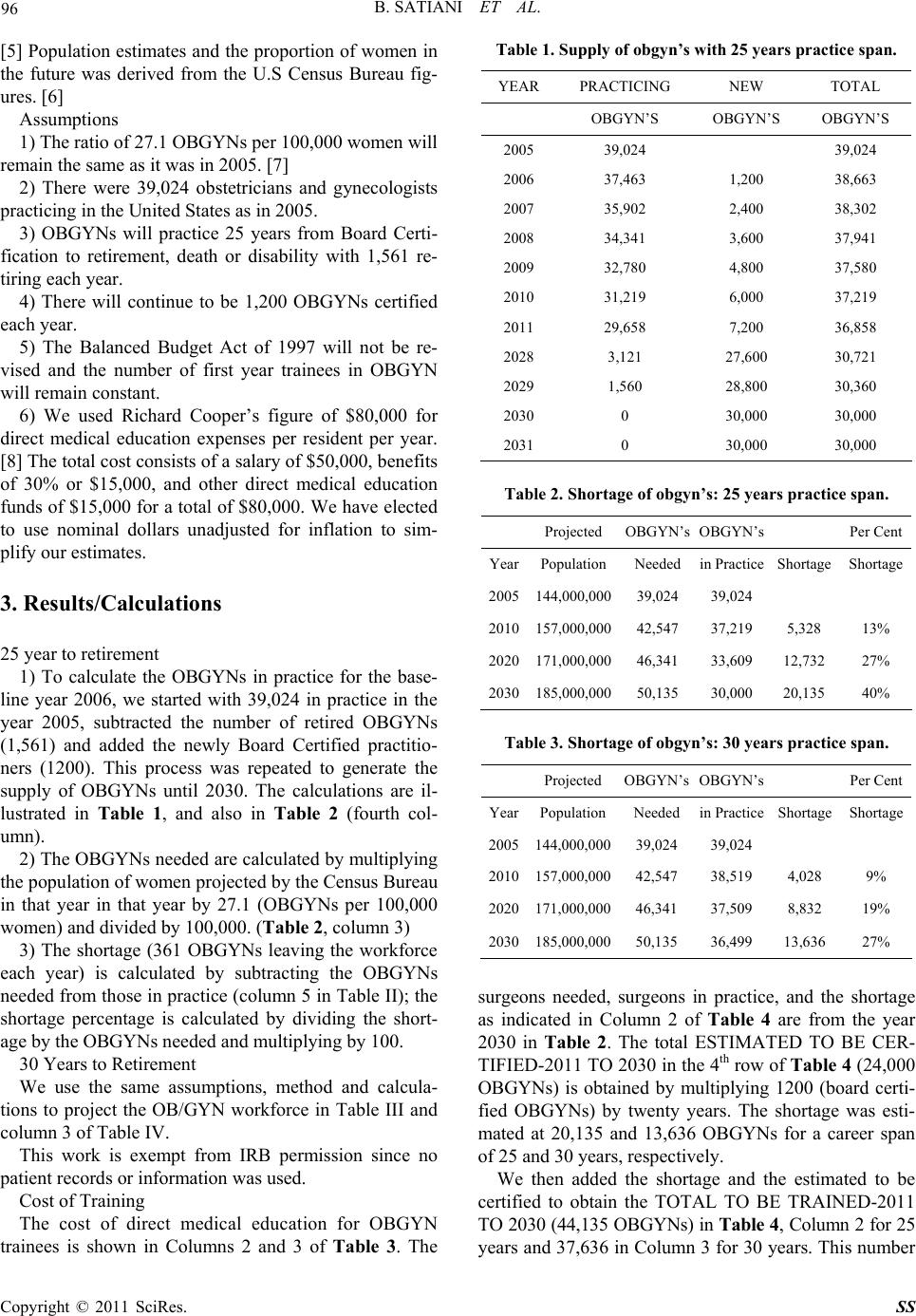

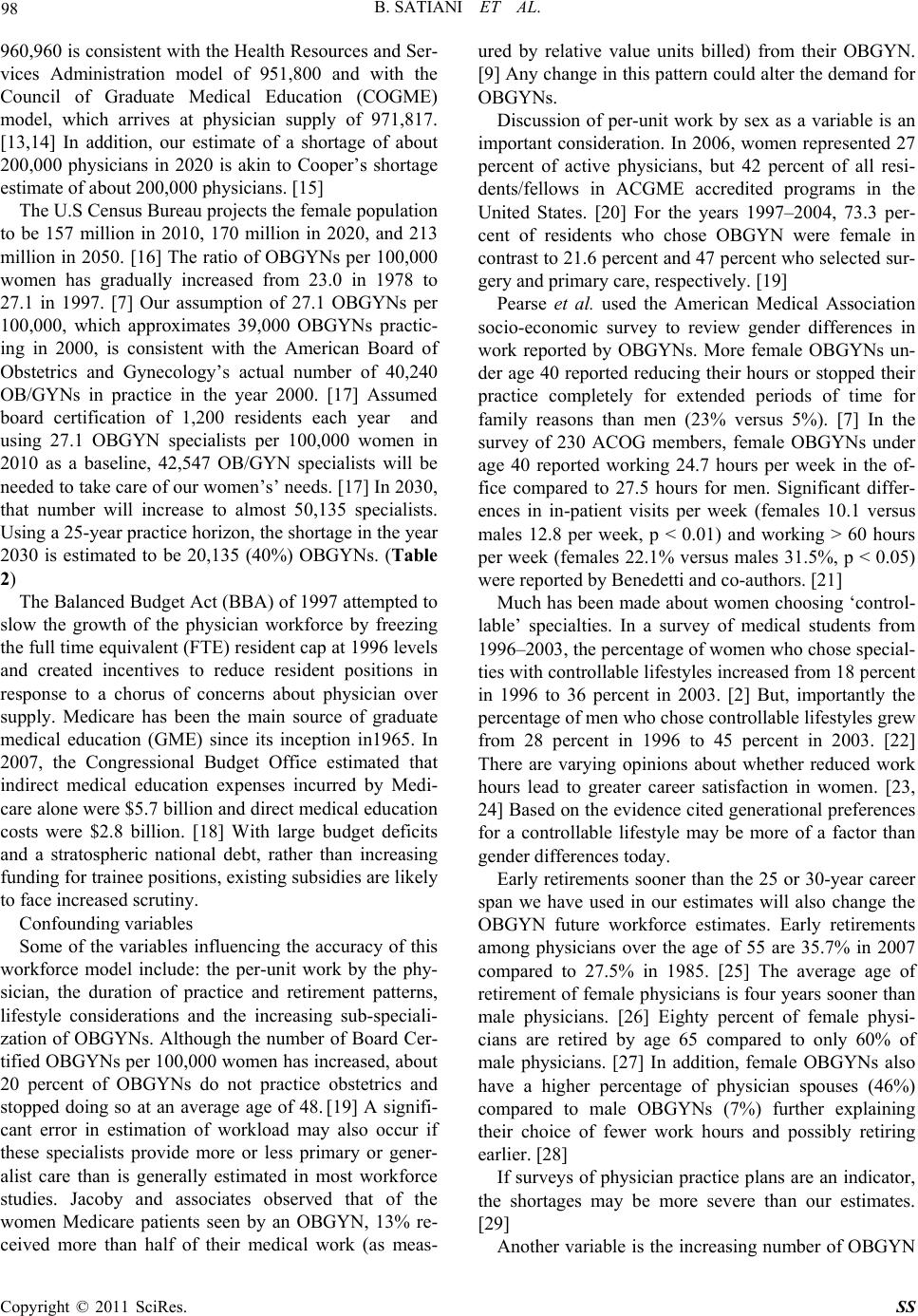

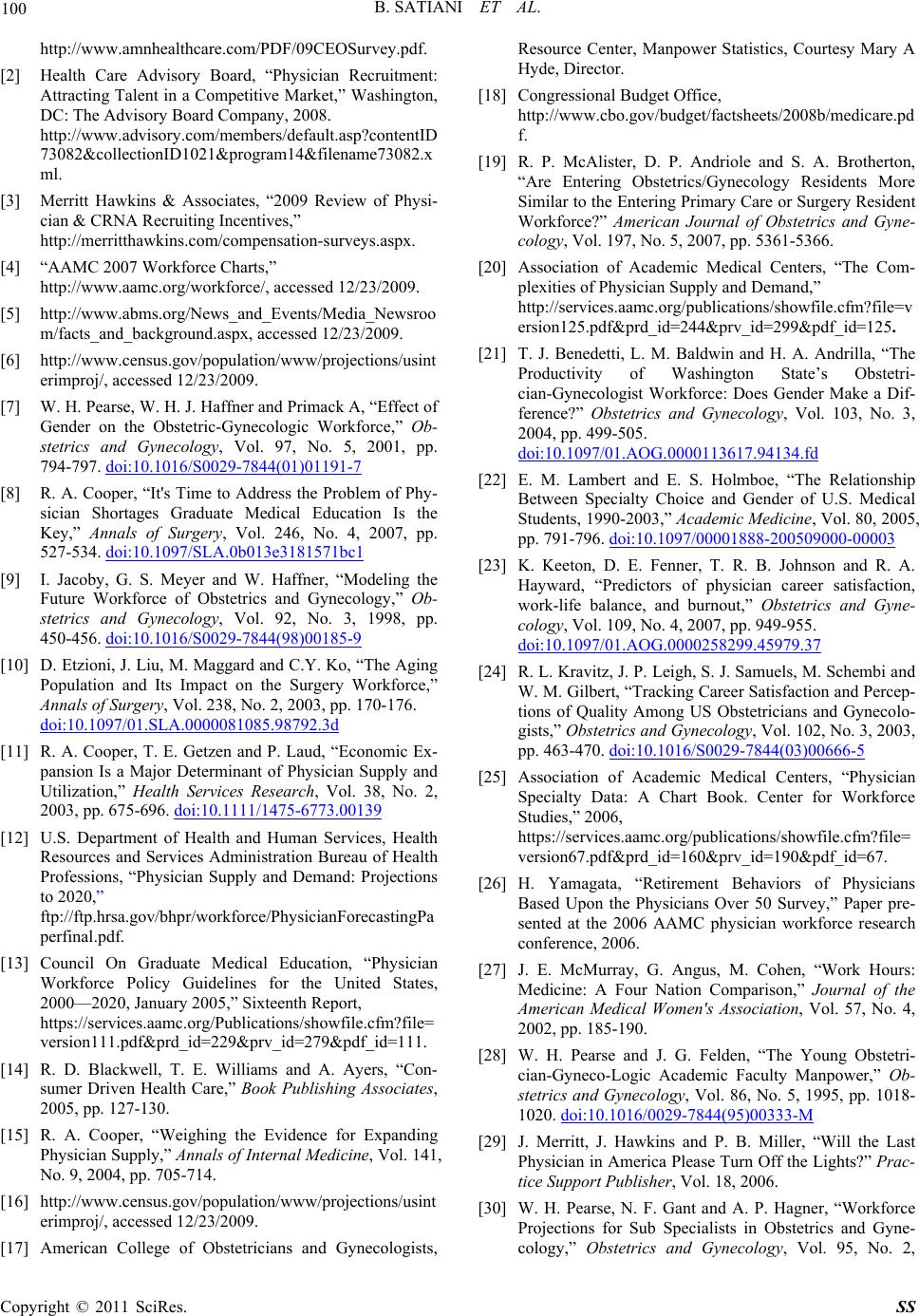

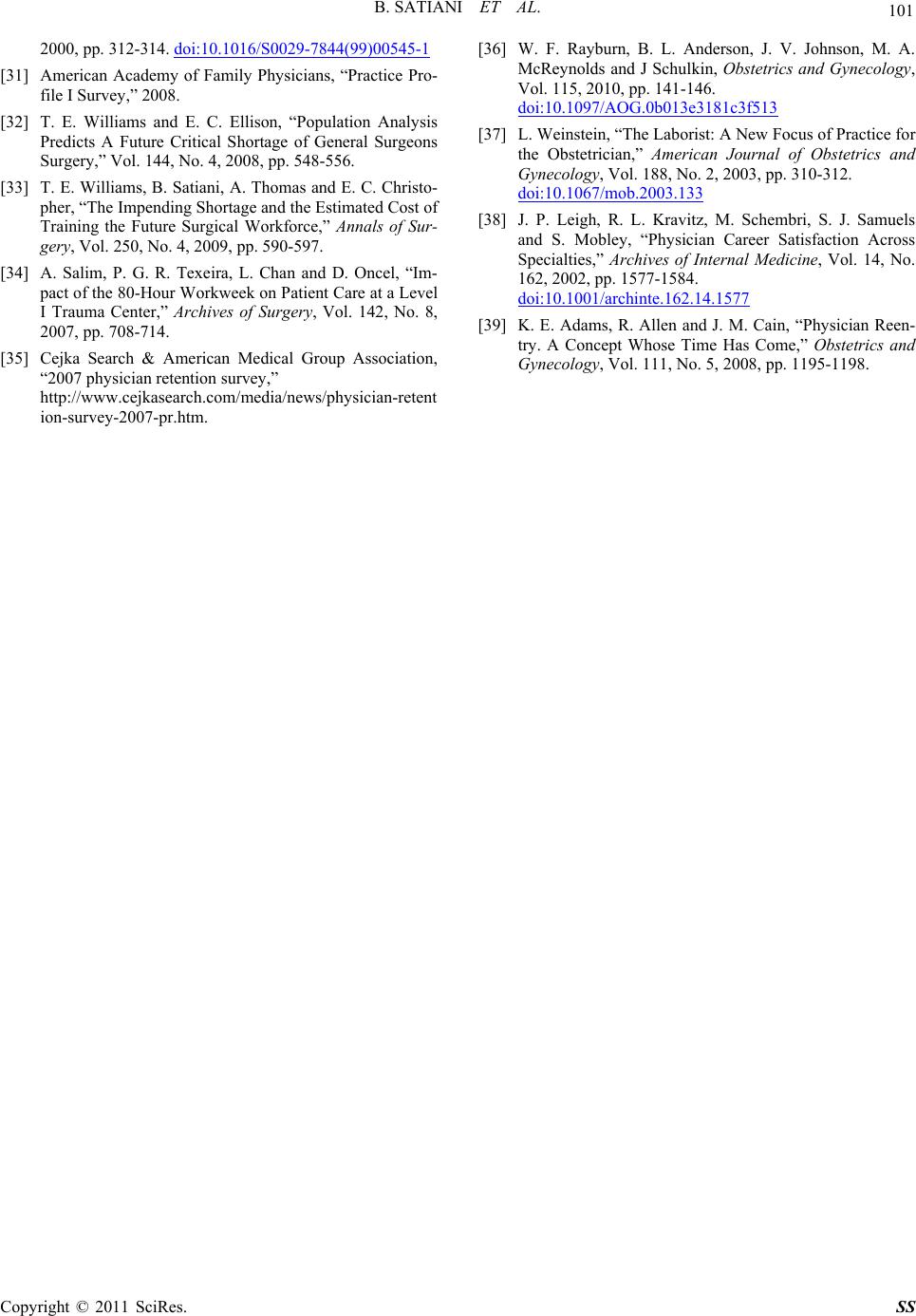

|