K. Yoshino et al. / Natural Science 3 (2011) 255-258

Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS

256

subjects while they watched a Japanese professional

baseball game at a stadium. We analyzed how their heart

rate responses to events during games correlated with

their subjective psychological states.

2. METHODS

Ten subjects (five females and five males between the

ages of 21 and 53 years) participated in the on-site

physiological data collection sessions, after providing

their informed written consent approved by the ethical

committee at AIST. All subjects were fans of the Hok-

kaido Nippon-Ham Fighters, a Japanese professional

baseball team, and had been to the Sapporo Dome to

watch Fighters’ games 28 to 250 times.

Subjects watched Fighters’ games at the Sapporo

Dome. We collected physiological data while they

watched the games. Eight subjects watched three games

(one in July, one in August, and one in September of

2008); one subject watched one game in September of

2008; and one watched two games in July and August of

2008. We collected a total of 27 cases. All subjects were

seated in the infield zone. We recorded their RR-inter-

vals with a wearable electrocardiogram device (Active-

Tracer, AC-301, GMS, Japan), from about 5 min before

the start of the game until 10 min after the end of the

game. Typically, the length of a baseball game is 180 min.

We also recorded video images of each subject’s be-

havior. Subjects watched their video images on a sepa-

rate day and recalled their subjective psychological

states at specific events as they watched the games. The

specific events were the Fighters’ and opponents’ scoring

and four fan service events. The four fan service events

were two types of dancing exhibitions, the Fighters’

cheering song, and a show by the Fighters’ mascot. The

subjects registered the intensity of their psychological

states on a 100 mm-long visual analogue scale (VAS)

questionnaire, for which the end points were labeled

“lowest” and “highest”. The questionnaire quantified the

intensity of eight psychological states: happiness, ten-

sion, fatigue, boredom, depression, anger, vigor, and

excitement. Tension, fatigue, depression, anger, and vigor

are scales on the well-known Profile of Mood States

(POMS) questionnaire [10]. In addition to these scales,

we adopted the scales happiness, boredom, and excite-

ment since these intensities vary greatly in an entertain-

ment environment. To reduce inter-individual variability,

we normalized the measured values of psychological

state intensity by transforming the data to a z-score for

each subject.

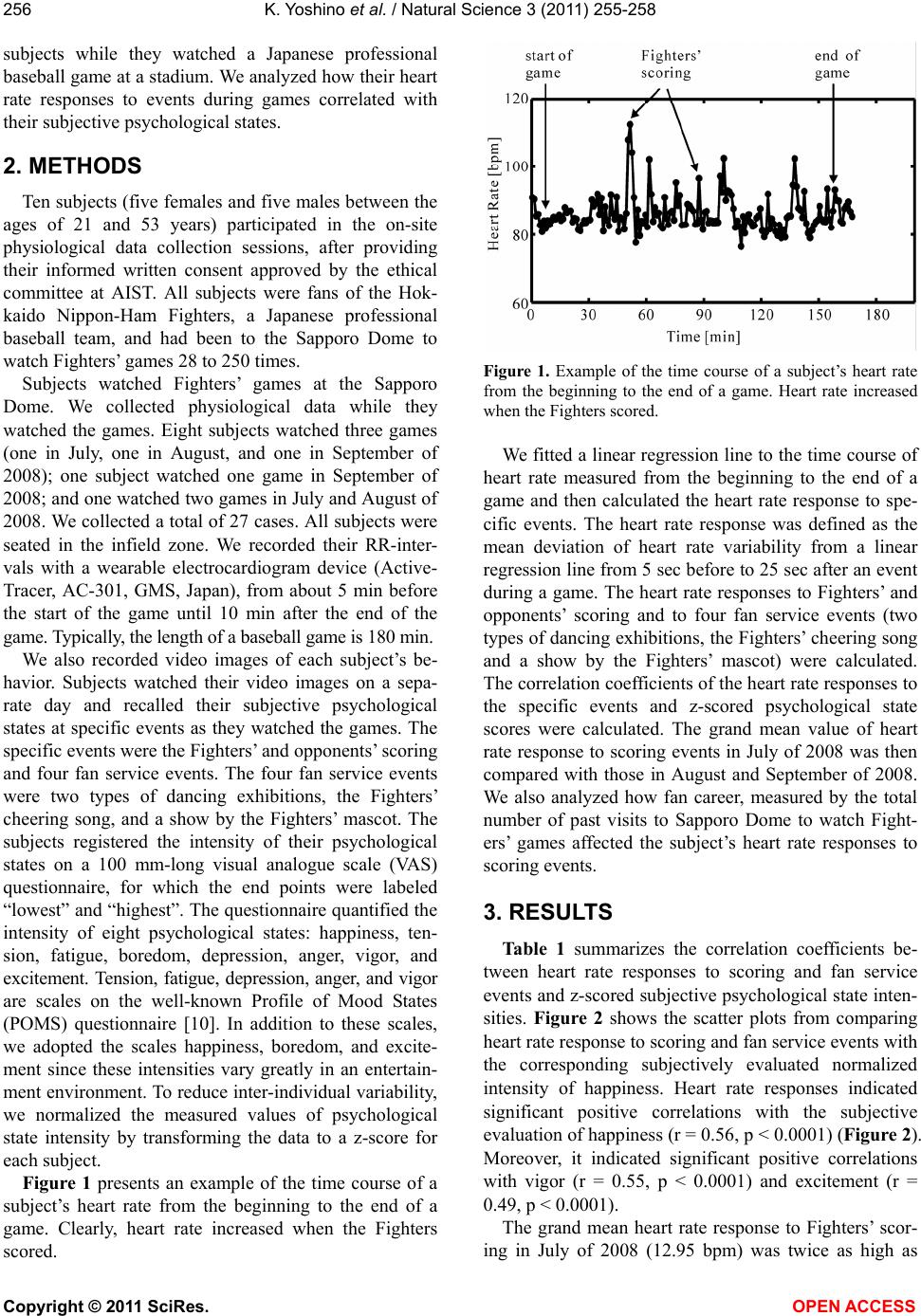

Figure 1 presents an example of the time course of a

subject’s heart rate from the beginning to the end of a

game. Clearly, heart rate increased when the Fighters

scored.

Figure 1. Example of the time course of a subject’s heart rate

from the beginning to the end of a game. Heart rate increased

when the Fighters scored.

We fitted a linear regression line to the time course of

heart rate measured from the beginning to the end of a

game and then calculated the heart rate response to spe-

cific events. The heart rate response was defined as the

mean deviation of heart rate variability from a linear

regression line from 5 sec before to 25 sec after an event

during a game. The heart rate responses to Fighters’ and

opponents’ scoring and to four fan service events (two

types of dancing exhibitions, the Fighters’ cheering song

and a show by the Fighters’ mascot) were calculated.

The correlation coefficients of the heart rate responses to

the specific events and z-scored psychological state

scores were calculated. The grand mean value of heart

rate response to scoring events in July of 2008 was then

compared with those in August and September of 2008.

We also analyzed how fan career, measured by the total

number of past visits to Sapporo Dome to watch Fight-

ers’ games affected the subject’s heart rate responses to

scoring events.

3. RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the correlation coefficients be-

tween heart rate responses to scoring and fan service

events and z-scored subjective psychological state inten-

sities. Figure 2 shows the scatter plots from comparing

heart rate response to scoring and fan service events with

the corresponding subjectively evaluated normalized

intensity of happiness. Heart rate responses indicated

significant positive correlations with the subjective

evaluation of happiness (r = 0.56, p < 0.0001) (Figure 2).

Moreover, it indicated significant positive correlations

with vigor (r = 0.55, p < 0.0001) and excitement (r =

0.49, p < 0.0001).

The grand mean heart rate response to Fighters’ scor-

ing in July of 2008 (12.95 bpm) was twice as high as