Creative Education 2011. Vol. 2, No. 1, 1-9 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/ce.2011.21001 Investigating Science Concepts in the Museum Like Treasure Hunting Nihal Doğan1, Seda Çavuş1, Savaş Güngören2 1 Faculty of Education, Abant İzzet Baysal University, Bolu, Turkey; 2Faculty of Education, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey. Email: nihaldogan17@gmail.com Received July 23rd, 2010; revised January 19th, 2011; accepted January 29th, 2011. In this research, the impacts of school trips on learning science subjects are studied with colorful science cards and a writing activity. These trips are aimed to be made in the informal learning environments such as Science and Technology Museums. In total, 34 pre-service teachers (21 female and 13 male) participated in this research. The trip was made to the Rahmi Koç Museum in Istanbul and before this trip, the participants were given some concepts and questions which were written on colourful cards in order to search in the museum regarding Science and Technology. After the field trip, they were asked to write and present an explanatory essay including the knowledge that they found about the questions and concepts written on the colorful science cards. At the end of this study, Activity Evaluation Scale, of which Cronbach’s α coefficient is 0.78, is applied in order to evaluate the participants’ efficiency in colorful science cards and the writing activity. According to the results, nearly all the participants stated that colorful science card activity was like treasure hunting and they found it quite enjoyable and didactic. In addition to this, the majority of the participants also stated that with the help of the essay writing which is performed after the trip, they learned how to summarize the knowledge they got dur- ing the trip, how to put their thoughts in order and associate the key thoughts which are defined in each subject, that is they learned how to organize the knowledge and how to arrange them. Keywords: Informal Learning, Writing to Learn, Science Teaching, Museum Education Introduction Human acquires various knowledge, skills and attitudes by himself through education, experience and trainings, which can be used in order to adapt to the rapid changes of the scientific and technological world. Education plays a very important role in the construction of the modern societies and to develop con- sciousness about the interactions between science and technol- ogy, as in the most developing countries. Education represents two main forms: formal and non-formal education, the latter includes the informal education (Demirel ve Kaya, 2003; Fidan ve Erden, 1993; Gelen, 2005; Gültekin, 2005; Şişman, 2006). Formal education; is described as teacher-centered, pre- arranged education in the frame of a definite goal and program and it is affiliated to an institution. These are graded learning environments in which students are concerned about their marks and evaluation is done at the end of it (Bozdoğan, 2007; Demirel ve Kaya, 2003; Fidan ve Erden, 1993; Gelen, 2005; Gültekin, 2005; Marsick ve Watkins, 2001; Şişman, 2006; Wellington, 1990). On the other hand, informal education does not include any plan or program; so, random learning occurs and individuals learn unconsciously through the interactions they have in a group and the situations they expose to (Alsop &Watts, 1997; Bozdoğan, 2007; Eshach, 2007; Fidan & Erden, 1993; Marsick & Watkins, 2001; Wellington, 1990). The informal education, which is also defined as natural education, occurs when new knowledge is added to the present knowledge. The new knowledge is discovered by the interaction of the individual with the environment or it is acquired spontaneously (Tezcan, 1992). Learning with formal education has considerably structured characteristics. As for informal education; the learn- ings during the informal education has less structured charac- teristics except planned informal education activities than for- mal education and learning shifts its direction from the teacher to the student (Gerber et al., 2001). In spite of the fact that formal and informal education are put forward as different facts, these two concepts should not be perceived as opposite and independent from each other. In traditional education system, from the time we were born to the formal education age in cognitive meaning, the knowledge and skills we acquire by informal ways both in family and in social environments prepare us to formal education. Formal and informal educations are complementary structures like the pieces of a puzzle (Demirel & Kaya, 2003). In different studies, it is stated that the field trips which are performed within the formal education, such as museums, aquariums, parks and sci- ence centres make the learning more effective (Bozdoğan, 2007; Rennie and Johnston, 2004). Also in many other studies, it is defined that the lessons which are made outdoor of the school, improve the students’ cognitive, social and emotional character- istics (Gerber, Cavallo & Marek, 2001). Informal environmen ts such as museums and science centres contribute to the learning quite a lot. Informal education deals with new topics and subject matters in Turkey. Science education and curriculum developers should give special attention to the use of informal environments to improve our students’ and teachers’ knowledge and attitude towards science.For this reason, informal environments as in many countries, should be cared much more as an education policy in Turkey and in newly changing science and technology  N. DOĞAN ET AL. 2 teaching programs. The revisions should be done by taking informal environments and their contributions into considerat- ion. Museum and Education In many developed countries, “museums” and “science centres” are considered as the most efficient environments for formal education. When their historical development is examined, the basic goal for their establisment is “education”. Museums provide lifelong efficient and active learning opportu- nities. International Council of Museums (ICOM) has published an issue named as “Ethics for Museums” in 2006; and in this issue, the social aspect of museums is defined as: “A non-profitmaking, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, and open to the public, which ac- quires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits, for purposes of study, education and enjoyment, material evidence of people and their environment.” Besides their responsibilities as archiving, collecting, safe- guarding and displaying various objects and cultural inheri- tance, museums take their place in society as educational and research institutions bearing the responsibilities of research and education (Bozdoğan, 2007). Today, it is moved away from traditional education, thus in addition to archiving and display- ing many kinds of objects, museums are seen as the identity of informal education institutions, as well (Çildir, 2007). When we look through history: the concept of “museum” began with making the present collections available for public viewing through exhibits. Then, after the social and cultural alterations in the Middle Age, museums again showed up themselves with Renaissance in which everyhing was collected about the nature and earth by discovering new continents (Tezcan Akahmet & Ödekan, 2006). “The Age of Enlightenm- ent” which began in France and the social mission of French Revolution became the initial point of public-oriented educational goals of museums. In England, where school education newly developed in 19th century, adult and child education was inadequate, so museums were seen as the places where people could get self-education (Hein, 2006). Educa- tional theorists (e.g. Comenius and J. Dewey) emphasized the importance of learners’ active participation and their interaction with the objects on learning; so, this would rise the substantial importance of education that occured in museums (Tezcan Akahmet & Ödekan, 2006). The increasing scientific and technological knowledge from the 20th century until today has affected the understanding of museums, as well. After 1950s, the rapid technical advance- ments in “Industrial Society” provided the development of interactive science museums, and after 1960s, these positive innovations in science museums have gained progress. “The Exploratorium” in San Francisco and “The Ontario Science Centre” in Toronto which took place in 1969, included exhibitions where learning occured with experiments. Besides teaching the knowledge and scientific principles which took place in school curriculum, these science centres enabled the learning of technological knowledge as biology, medicine, astronomy and space with interactive moduls. In recent years, museum education has gained importance in Turkey. Until 1990s, the role of museum in education took place only in governmental programs. It was mentioned in various meetings and seminars. According to these, various proposals and decisions were introduced; but, these are not applied (Tezcan Akahmet & Ödekan, 2006). In the following years, master programs were founded in universities to make an academic ground for this field and “museum education” context was constituted by researches. Also, several studies were started by some associations in order to establish science and technol- ogy museums. The Ministry of Education prepared a connec- tive study in 2008 which include “museum and education” frame into the associated subjects of the school programs and this frame is now applied in primary schools with related school subjects. According to this study, adequate explanations were introduced according to the acquisitions of the lessons as Turkish, Mathematics, Social Studies, Knowledge of Life (Life Sciences) and Science and Technology lessons. The aim of this study was to associate formally presented traditional education with activities that took place in museums and other informal environments. The major science and technology centres in Turkey are; Rahmi M. Koç Industrial Museum, Şişli Science Centre, Deneme Science Centre in İstanbul; Feza Gürsey Science Centre, Energy Park, METU Science and Technology Museum in Ankara. As it is seen above, although Turkey has 81 cities, the number of Science and Technology Museums are limited. We have accomplished our study in Rahmi M. Koç Industrial Museum in Istanbul. This museum first opened its doors to visitors in 1994 and took its current condition with the addings to the building in 2001 and 2007. It is devoted to transportation, industry and communication history and it is different from the classic exhibition museums; it has a different museum understanding that people can touch the objects in there. The collection contains 8.000 objects. The museum has 9 depart- ments including motorway transportation, railway transporta- tion, aviation, naval, engineering, communication, scientific tools, try and learn models, and toys (Figure 1). The objects in these departments came from all over the world and they are grouped systematically and displayed chronologically. These exhibitions not only provide people the opportunity to observe and examine the historical development of scientific and tech- nological advancements tangibly, but also enable them to learn by strengthening their knowledge in the exhibition activities which take place in try and learn moduls and enjoy all these. Many researches stated that the number of trips to history museums or science and technology museums were quite low in Turkey (Bozdoğan, 2007; Bozdoğan & Yalcin, 2006). It is thought that physical impossibilities prevent these kinds of activities (Çıldır, 2007; Güleç & Alkış, 2003). The visitors generally visit these places with school trips. The number of “Science and Technology Museums” and “Science Centres” are so few and the available ones are in big cities, so these are two reasons of the low visit numbers to these places. The teaching programs changed in Turkey in 2004; however, the traditional formal education is still going on in school buildings and, museum education is not being done with essential importance. The impact of different activities on science teaching and participants’ attitudes in informal environments are studied in this research. Also, it is aimed in this study to introduce the museums to the pre-service teachers and show this study as a sample model to get the most efficient benefit from informal environments. It is thought that this study will provide the re-  N. DOĞAN ET AL. 3 Figure 1. Some examples of objects on display in the Rahmi M. Koç Industrial Museum in Istanbul. Attitude Scale Analysis of Attitude Scale Writing activity Science and technology museum trip Figure 2. Context of the current study. quired attention for science teaching in museums in Turkey. Methodology How the data was collected? (Figure 2) The sample for this study consisted of 34 preservice teachers from Turkey. The 21 of them were females and 13 of them were males , and they were sophomores in Elementary Science Education Department of the University. Data Collecting Tools Attitude Scale: The participants completed this scale two times; before and after the trip to Rahmi Koç Museum to determine the changes in their attitudes towards Science lesson. Attitude Scale is comprised of likert type scale, which has acceptable Cronbach's alpha (α = 73) coefficient (Geban et al., 1994; Bozdoğan, 2007). The items in the scale are five-point scale (0-5), with the total possible score being 5 points. Attitude scale includes 25 de- clarative statements and 5 options as “Strongly disagree”, “Agree somewhat”, “Agree”, “Quite agree” and “Strongly agree”, and it is assigned numbers from 1 to 5. The individuals’ proportions to agree with the items are; “In scoring the students’ answers, the scores for positive items are considered as: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and for the negative items as: 5, 4, 3, 2, 1”. With this procedure, scores may range from 25 to 125; the higher score indicates a more positive attitude about science and the role of field trip. The Questionnaire of Views about Museums: The participants’ opinions about Science and Technology Museums were examined two times; before and after the trip to Rahmi Koç Museum with “The Questionnaire of Views about Museums” which included 11 open-ended questions. Scientific Concept Cards: The small colorful cards were given to participants before the Views of science and technology museum questionary (MHGA) Colorful Science Cards MHGA Analysis Interview analysis Interview  N. DOĞAN ET AL. 4 trip to the Rahmi Koç Museum in Istanbul. Some scientific concepts and questions were written on these cards, and the participants were asked to search them in the museum. Some of the concepts that were written on the cards are below: Steam Turbine Zoetrope Telescope Periscope Thermostat Why was the front wheel bigger in the first made bicycles? How is the atmospheric pressure adjusted in the planes? It was expected from participants to collect information about these concepts and write an explanatory essay about them. The participants were divided into groups including 3 or 4 students and they are asked to search these concepts in the museum. The groups found the related departments in the museum according to their concepts and questions in their cards and they got the detailed information from the person who was responsible for that department. It was expected from the participants to discuss the concepts or the questions in their cards within their groups and write an informative essay about them and then, the groups presented their essays to the class. Semi-Structured Interview: The opinions of the participants on the writing activity and science cards were tried to be put forward with semistruc- tured interview. Data Analysis The data was collected in different steps. The contribution of museums on teacher education is examined in this study. Beside this, the impact of the science cards and writing activity on learning science and technology concepts which were applied in this kind of field trips were also evaluated. In this study, none of the participants had ever been in Rahmi Koç Museum in Istanbul. Step 1: In order to study whether or not the trip affects the pre-service teachers’ attitudes and opinions, the “Attitude Scale” and “The Questionnaire of Views about Museums” are applied twice, before and after the trip. Step 2: After the trip, “Semi-Structured Interview” is done to put forward the pre-service teachers’ detailed opinions about the trip. Step 3: ‘Activity Assessment Scale’ is applied to receive the participants’ opinions on science cards, which help them to learn different concepts that they come across in the museum, and to implement the writing activity afterwards. Results Step 1: Attitude Scale: In data analysis, Paired samples t-test analysis is used to define whether there is any difference in terms of attitudes before and after the pre-service teachers’ trip to Rahmi Koç Museum. According to the paired samples t-test results, the trip affects the pre-service teachers’ (p < 0.05) attitudes considerably in statistical meaning (Table 1). These differences between pre-test and post-test attitude scales are in the positive direction. The Questionnaire of Views about Museums: According to the results of ‘The Questionnaire of Views about Museums’, the participants gave almost the same answers for the questions about museums, science and technology before and after the museum trip; so, it is concluded that area trip does not affect pre-service teachers’ opinions about museums. In the following, some of the questions at “The Questionnaire of Views about Museums and the answers of participants” that are given. The question is “What is museum?” and 90% of the particip- ants replied as: - Museums are interesting places and they provide learning. They are also the places where cultural heritage is preserved and the objects about science and technology are exhibited. - They are the places where culture and knowledge are transfered with experience and joy. The exhibition area of different and diverse cultures. The places where people have a chance to socialize. - A central body which unites theoretical knowledge with visuals. The question is “When did you do your last museum visit?” According to the answers, 70.59% of participants replied this question as they have never been to a museum. The 29.41% of them replied as they have been to a museum; however, 8.82% of them attended with their family and 20.59% of them attended with school trips in secondary school or in high school. The mesums that they have visited are public museums as Ha- gia Sophia, Topkapı Palace and Museum of Anatolian Civilizations and also the War Museum in the Atatürk’s (the founder of Turkish Republic) Mausoleum. The majority of the participants (85%) stated that they like the department where old and modern technologies are displayed, because this place enables the comparison of old and modern technologies. As it can be seen from the results, museum visiting with family is quite low. The question is “What is science?”. 85% of the participants stated that it is an instrument which eases people’s lives. Three students replied this question different from their friends. One of them defined it as the sub-branch of philosophy, the other defined it as the unit of methodologies. However, the third stu- dent defined it as an explanation of human activity in nature with the relations among disciplines. It is a gladsome result that this student has a post-positivist approach. Another question is “What was the most conceptual thing or what was the most thought provoking thing for you In Rahmi Koç Museum?” and “Why is this so?” As an answer to this Table 1. The Paired samples t-test results of Participants’ Pre-test and Post-test Attitude Scales. N X S sd T p Attitude Pre-test 34 101.9231 10.01 33 2.43 0.02 Attitude Post-test 34 106.4615 9,79  N. DOĞAN ET AL. 5 question, the participants stated that the rapid development of technology is very impressive. It becomes very significant that all the participants see the changeability of scientific knowledge in there. Next question is “What is technology?” 100% of the participants stated that they are the studies which make people’s life easy. Another question is “Do you follow the news about science and technology and museums?” If your answer is “Yes” then “What is your news source?” The majority of pre-service teachers (89%) replied this question as they followed the news about science and technology via internet, TV and newspapers, but they did not have any information about museums and they stated that this trip was their first scientific museum trip. Pre-service teachers stated the reasons of low visiting rates in museums as in the following: Inadequate information about museums, Ignorance towards museums among the society, Difficulties in arrival to museums and economic impossi- bilities, Inadequate publicity of museums, Museum education is not included in the curriculum of primary and secondary schools, Science centres are only situated in 3 big cities of 81 cit- ies, Teachers are unconscious and irrelevant in this subject, The role of museums in science education is not clearly explained to the teachers or pre-service teachers. People, especially teachers, are scared of taking respons- ibility for this kind of museum trips. The last question is “Has this trip affected your relations with your friends positively or negatively?” Three of the participants stay neutral, however 88.23% of the participants express posi- tive statements. The participants’ answers are given in the fol- lowing: It has affected positively. Socializing has increased in the class. We had a chance to know our friends closely. We had fun. It enabled us to listen and understand each other. Step 2: Semi-structured Interview: In this study, semistructured interviews are analyzed in order to learn the participants’ opinions about science card activity which they had during the museum trip, and the writing activity afterwards with the group or individually. The participants’ answers were read several times and various themes were con- structed from them. Especially it was emphasized that how participants perceived colorful cards and writing activity and what were their opinions on the usage of them in the museum; after these, the themes were constructed accordingly. The themes which are formed as a result of the semi-structured inter- view and the codes under these themes are turned to a table. Some of the questions and the code tables can be seen below as examples: QUESTION 1: Can you evaluate the science-card activity during the museum trip positively or negatively? The majority of the participants stated that card activity has positive effects on the informal learning environments. (Table 2). These positive effects are; learning with realizing and focusing on even the unattractive things and increasing the curiosity. Beside these, they emphasized that, in order to find the science card concepts, they had a chance to examine everything in details in the museum and science centre. QUESTION 2: Can you evaluate the didactic writing activity with your group or individually before and after the trip? It is stated by all the participants that the writing activity after the trip regarding the questions or the concepts that are searched by them during the trip, is “informative”. Besides this, it is emphasized that the writing activity is an important Table 2. The Frequencies of the codings regarding science card activity. Codings Frequency (N:5) 1 Enables calculated research. 1 2 Conscious learning takes place. 4 3 Increases curiosity. 1 4 Turns even the most unattractive things into a focal point. 2 5 Enables detailed research. 3 6 I perceived it as a homework. 1 Table 3. Frequency codings regarding writing activity. Coding Frequency (N:5) 1 Enables learning 5 2 Entertaining 2 3 Enables inter-discipline among concepts 1 4 Improves imagination 1 5 Improves creativity 3 6 Makes use of the most basic principles (foreknowledge) 2 7 Improves writing skills 1 8 Improves self- expression 1 9 Enables permanency 2 10 Makes use of verbal–linguistic intelligence 1 11 Enables to write down the observations 2  N. DOĞAN ET AL. 6 education strategy because it is quite creative, improves imagina- tion and full of fun (Table 3). It is indicated that the writing activity enables permanency in education, helps participants to put forth their writing style and develop their written expression skills by writing their thoughts, knowledge and observations. In this research, writing activity is applied both as a group and individually. It is aimed by asking the question “Which writing activity is the most effective? (Table 4) The group activity or the individual one?” to examine which activity is found more effective and why? According to the results, two of the participants considered the individual activity more effective, and the other two thought the group activity more effective. However, one of the participants stated that both of them are units of a whole. Individual and group writing activity codings and frequencies are given in the following. (Table 5). “Are you going to use writing activity when you become a teacher?” The participants reply this question as they may use it in different subjects. Activity Evaluation Scale: The views of the students about science card, discussion and writing activity in the Rahmi Koç Museum is examined with the “Activity Evaluation Scale”. According to the pre-service teach- ers’ answers to the questionnaire, the participants stated that writing activity contributes to learning new information (91.4%), enables to revise old knowledge (62.9%) and enjoyable (54.3 %). Besides these, they stated that it is necessary to spend more time and labor for the writing activity. Conclusion and Dıscussion In recent years, field trips to science centres and science and technology museums have gained importance in Turkey; because, those places enable students enjoyable and effective science education. When we compared many developed countries with Turkey, the interest in museums is still unsatisfactory in Turkey. In those developed countries, the museum education has a great importance in their educational programs and educational policies. There are a lot of science centres and museums in developed countries as discussed above; however, the number of museums and science centres in Turkey are quite low and the available ones are in big cities. These reasons hinder them to become focal point and also they prevent a formation of museum culture. Eshach (2007) came to “Çanakkale 18 Mart University” for a workshop about inquiry events and he surprised that there is no science centre in Çanakkale and nearby. In their studies, Pisci- telli and Anderson (2001) determined that the majority of students (75%) have visited different museums more than several times; however, only the 12% of them have never been in a museum before. According to this study, the 75% of students visited museum with their parents, 69% of them visited with their elder brothers or sisters, 11% of them visited with their grandparents, uncles or aunts, 14% of them visited with their schoolmates, and only the 9% of a student group stated that they visited museums with their teachers (quoted from Bozdoğan, 2007). According to the results of this study, there is a big surprise for researchers that all the pre-service science teacher participants have never been in a science and technology museum and 70.59% have never been in any kind of museums before they attended to university. The 29.41% of the participants stated that they have visited a museum and, 8.82% of them visited with their parents and the 20.59% of them visited with their teachers in secondary or high school via school trip. One of the most important findings in this study is museum visiting with parents in Turkey is quite low when it is compared to developing countries. These findings show that museum culture in Turkey is newborn. The pre-service teachers had a chance to see a science and technology museum for the first time thanks to this field trip which are quite important for science lessons; so, this study is very important in this aspect as well. There are many studies which emphasized the importance of environments outside the class, such as science centres, aquariums, and zoos to teach especially the discrete concepts which are very difficult to learn in class environments; so, the informal environments affect the attitudes towards science and success in science (Falk, 1983; Lucas, 2000; Pedretti, 2002; Tabel 4. Frequency codings of the effects of individual writing activity. Coding Frequency (N:5) 1 Acquiring information 1 2 Expressing feelings and opinions 2 3 Time wasting 1 4 Transfering experiences 1 5 Monolog writing 1 6 Transfering scientific and intellectual ideas 1 Tabel 5. Frequency codings of the effects of group working in writing activity Coding Frequency (N:5) 1 Learning more than one concept occurs 2 2 Teaches how to study with a group 2 3 Completes the missing information 3 4 Enables sharing information 2 5 Enables communication and interaction among people 2 6 Decreasing performance 1 7 Brainstorming 1  N. DOĞAN ET AL. 7 Kisiel, 2005). In this study, all the participants stated that they were impressed positively by the trip and learned science concepts while enjoying the trip. After a 6 hours entertainment-oriented museum trip by Champagne (1975), he stated that some displayed objects in science museums are described as “sloopy science” and their actual meanings are uncertain, and science and technology can be introduced ethics-free easily and without any problem. On the contrary to the Champagne’s results; it is revealed in this study that pre-service teachers expressed that they enjoyed the time in the science and technology museum, and they stated that they were surprised at the rapid progress of science and technology by observing the changes of many objects (telescope, bicycle, car, ship etc.) throughout the time. The participants even stated their disturbance about the situation which shows that Turkey falls behind the west in terms of many developments in science and technology. According to this scientific field trip, it is determined from semi-structured interviews that pre-service teachers grasp the characteristics of the nature of science such as; scientific knowledge is changeable and it can be affected by the socio-cultural environment. In their studies, Shortland (1987) and Wymer (1991) stated that entertainment and science can not coexist. On the contrary to Shortland and Wymer, the participants in this study stated that they enjoyed during the trip and acquired knowledge regarding the questions and science concepts (Table 6). Beside these, they emphasized that their creativity and imagination improve their social relations with their friends. It is considered that science cards and writing activity have impacts on the participants’ positive opinions. However, in order to make generalizations, this research should be implemented with a bigger sampling frame and in a different informal environment. It is reported in many studies that informal learning environments increase the attitudes, interest and motivation towards science positively and also provide unconscious/ random learning (Marsick and Watkins, 1990; Ayres and Melear, 1998; Rennie, 1994; Wolins, Jensen & Ulzheimer, 1992). The results of this study also similar with those researches’ results. As recommended in many studies, in order to get more contribution from the museums, it is necessary to motivate and prepare students well before the museum trips. In order to provide this, the colorful science cards and the questions were given to the participants and they were asked to find the relevant concepts and answers in the museum. The participants resembled the colorful science cards and question searching activity with the “treasure hunting” and the title of this article was inspired from this. The scientific concept cards help to look around the museum very consciously, and as the participants stated, these cards also made the trip more enjoyable. Besides these, the participants indicated that these kinds of activities enable opportunity to get more contribution from the informal learning environments. These results are supported by the findings in the literature, as well. According to many researches, it was found that the appropriate manipulations before and during the trip to museums and science centres increased the learning and motivation (Rennie et al., 2003; Crane, 1994). The colorful science cards and writing activity in a field trip have positive effects on learning science subjects, and this is an important result of this study. The participants stated that they learn unconsciously and writing activity improve their creativity and imagination, and also scientific area trip increases their curiosity towards scientific concepts. It is stated in different studies that using writing activity in sicence classes as a learning strategy enables self-learning/metacognition for the students (Vygotsky, 1962; Hayes, 1987; Langer and Applebee, 1987; Rivard, 1994). Halliday and Martin (1993) emphasized that writing activity affects students’ point of view and provide different paradigms. This study also carries the characteristic of being a “sample model” to show the necessary preparations before the field trips and the different activities that can be applied in different environments for pre-service science teachers. It is not a suprising result for us that the pre-service science teachers who have never been in a science and technology museum, stated that they evaluated the applied activities quite different and they also gained a different experience. According to the results of this study, it is concluded that doing the science lessons in the museums and science centres will enable meaningful learning, makes science lessons more enjoyable and can take the students away from the class for a while and so this enables to grow up scientific literate of individuals who understand how science, technology and society affect each other and who can use their knowledge in daily decision-making mechanisms in Turkey. Outdoor classroom or field trip is dealing with new topics and subject matter in Turkey. It is especially required to raise awareness among science teachers about informal learning environments. It is a quite important step putting the “informal learning” course as an elective course in faculties of education. Accord- ing to evidences that we obtained from this study, further rec- ommendations are needed for the following stages: It is necessary to make the required arrangemets in science and technology education program which was changed in Turkey in 2004 and the responsibility for being a part of science education should be given to the museums. The number of science and technology museums and science centres should be increased immediately in all cities. If it is not possible to constitute museums and science centres in all cities, then mobile museums and science centres should be generated so, they can be transported to the schools. There should be established a bridge between schools and Table 6. Percentage of the results relating to the different categories of all the participating impacts. Science learning 100% Enjoyment 97,05 % Changed attitudes to science 88,23 % Improving Imagination and Creativity 80 % Improving Social Interaction 40%  N. DOĞAN ET AL. 8 the museums. An awareness should be raised among all teachers and pre-service teachers about informal learning/teaching. Learning science subjects can be made more enjoyable with the scientific field trips by doing different activities such as making colorful cards and writing activities. Besides formal education, new strategies and educational policies should be developed, implemented and generalized about informal education in every stage of education, and an awareness should be raised in public about museum education. References Alsop, S., & Watts, M. (1997). Sources from a somerset village: A model for informal learning about radiation and radioactivity. Science Education, 89, 33-50. Anderson, D., Lucas, K. B., Ginns, I. S., & Dierking, L. D. (2000). Development of knowledge about electricity and magnetism during a visit to a science museum and related post-visit activities. Science Education, 84, 658-679. doi:10.1002/1098-237X(200009)84:5<658::AID-SCE6>3.0.CO;2-A Anderson, D., Kisiel, J., & Storksdieck, M. (2006). Understanding teachers perspectives on field trips: Discovering common ground in three countries. Curator, 49, 365-386. doi:10.1111/j.2151-6952.2006.tb00229.x Ayres, R., & Melear, C. T. (1998, April). Increased learning of physical science concepts via multimedia exhibit compared to hands-on exhibit in a science museum. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, San Diego, CA. Bozdoğan, A. E. (2008). İnformal eğitim çevrelerine yapılan Gezilerin planlanması ve değerlendirme çalışmaları: Enerji parkı örneği. Eğitimde Kuram ve Uygulama, 4, 282-290. Bozdoğan, A. E., & Yalçin, N. (2006). Bilim merkezlerinin ilköğretim öğrencilerinin fene karşı ilgi düzeylerinin değişmesine ve akademik başarılarına etkisi: Enerji parkı. Ege Eğitim Dergisi, 2, 95-114. Bozdoğan, A. E. (2007). Bilim ve teknoloji müzelerinin fen öğ- retimindeki yeri ve önemi. Yayınlanmış Doktora Tezi, Gazi Üni- versitesi Eğitim Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Ankara. Champagne, D. W. (1975). The Ontario science center in Toronto: Some impressions and some questions. Educational Technology, 15, 36-39. Demirel, Ö., & Kaya, Z. (2003). Öğretmenlik mesleğine giriş (3.baskı). Ankara: Pegem Akademi Yayıncılık. Dierking, L. D., Falk, J. H., Rennie, L., Anderson, D., & Ellenbogen, K. (2003). Policy Statement of the “informal science education” ad hoc committee. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 40, 108-111. doi:10.1002/tea.10066 Eshach, H. (2007). Bridging in-school and out of school learning: Formal, non-formal, and informal education. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 16, 171-190. doi:10.1007/s10956-006-9027-1 Falk, J. H. (1983). Field trips: A look at environmental effects on learning. Journal of Biological Education, 17, 137-141. doi:10.1080/00219266.1983.9654522 Falk, J. H., Ed. (2001). Free-choice science education. New York and London, Teachers College, Columbia University. Fidan, N., & Erden, M. (1993). Eğitime giriş (3. Baskı). Ankara: Meteksan Matbacılık. Geban, Ö., Ertepınar, H., Yılmaz, G., Altın, A. & Şahbaz, F., (1994). Bilgisayar destekli eğitimin öğrencilerin fen bilgisi başarılarına ve fen bilgisi ilgilerine etkisi. I. Ulusal Fen Bilimleri Eğitimi Sempozyumu: Bildiri Özetleri Kitabı, 9, 1-2, Eylül Üniversitesi,. İzmir. Gelen, İ. (2005). T. K. M. ÖZTÜRK, (Ed.), Öğretimde planlama ve değerlendirme. İstanbul: Lisans Yayinlari. Gerber, B. L., Cavallo, A. M. L. & Marek, E. A. (2001). Relationships among informal learning environments, teaching procedures and scientific reasoning ability. International Journal of Science Edu- cation, 23, 535- 549. Gültekin, M. (2005). Öğretimde planlama ve değerlendirme, Eskişehir, T. C. Anadolu Üniversitesi Yayını, 1317, http://books.google. com/ books?id=3d_jUUWrzr8C&hl=tr. Halliday, M. A. K. & J. R. Martin. (1993) Writing science: Literacy and discursive power. London: The Falmer Press. Hayes, D. A. (1987). The potential for directing study in combined reading and writing activity. Journal of Reading Behavior, 19, 333-352. Hein G. E. (2006). Museum education. In: S. Macdonald, (Ed.), A companion to museum studies (pp. 340-352). Blackwell Publishing Ltd. doi:10.1002/9780470996836.ch20 International Courcil of Museum (ICOM) (2006). ICOM code of ethics for museums. France. Kisiel, J. (2005). Understanding elementary teacher motivations for science fieldtrips. Science Education, 89, 936-955. doi:10.1002/sce.20085 Köseoğlu, F., Atasoy, B., Kavak, N., Akkuş, H., Budak, E., Tümay, H., Kadayifçi, H., & Taşdelen, U. (2003). Yapılandırıcı öğrenme ortamı için: Bir fen ders kitabı nasıl olmalı. Ankara: Asil Yayın Dağıtım. Langer, J. A., Learning through writing: Study skills in the content area. Journal of Reading, 29, 400-406. Lucas, K. B. (2000). One teacher’s agenda for a class visit to an interactive science center. Science Education, 84, 524-544. doi:10.1002/1098-237X(200007)84:4<524::AID-SCE6>3.0.CO;2-X Marsick, V. J., & Watkins, K. E. (2001). Informal and incidental learning. New Directions For Adult And Continuning Education, 89, 1-102. Pedretti, E. (2002). T. Kuhn meets T. Rex: Critical conversations and new directions in science centres and science museums. Studies in Science Education, 37, 1-42. doi:10.1080/03057260208560176 Piscitelli, B. & Anderson, D. (2001). Young children’s perspectives of museum settings and experiences. Museum Management and Cura- torship, 19, 269-282. doi:10.1080/09647770100401903 Rapp, W. (2005). Inquiry-based environments for the inclusion of students with exceptional learning needs. Remedial And Special Education, 26, 297-310. doi:10.1177/07419325050260050401 Rennie, L. J. (1994). Measuring affective outcomes from a visit to a science education centre. Research in Science Education, 24, 261-269. doi:10.1007/BF02356352 Rennie L. J., & Johnston, D. J. (2004). The nature of learning and its implications for research on learning from museums. Science Education, 88, 4-16. doi:10.1002/sce.20017 Rennie, L. J., Feher, E., Dierking, L. D., & Falk, J. H. (2003). Toward an agenda for advancing research on science learning in out-of-school settings. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 40, 112-120. doi:10.1002/tea.10067 Rivard, L. P. (1994). A review of writing to learn in science: Implications for practice and research. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 31, 969-983. doi:10.1002/tea.3660310910 Shortland, M. (1987). No businiess like show business. Nature, 328, 213-214. doi:10.1038/328213a0 Şahan M. (2005). Gazi Üniversitesi ve Türk Eğitim Bilimleri Dergisi, 4, Ankara: Pegem A yayincilik. Şişman, M. (2006). Eğitim bilimine giriş, Ankara: Pegem A yayincilik. Tezcan Akahmet, K., Ödekan, A. (2006). Müze eğitimin tarihsel gelişimi. İTÜ Dergisi/b, 3, 47-58. Tezcan, M. (1992). Eğitim sosyolojisi, Ankara: Zirve Ofset. Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. doi:10.1037/11193-000  N. DOĞAN ET AL. 9 Weber, L. (1971). The English infant school and informal education. U Prentice-Hall. Wolins, I. S ., Jensen, N., & Ulzheimer, R. (1992). Children’s memories of museum field trips: A qualitative study. Journal of Museum Education, 17, 17-27. Wymer, P. (1991). Never mind the science, feel the experience. New Scientist, 49.

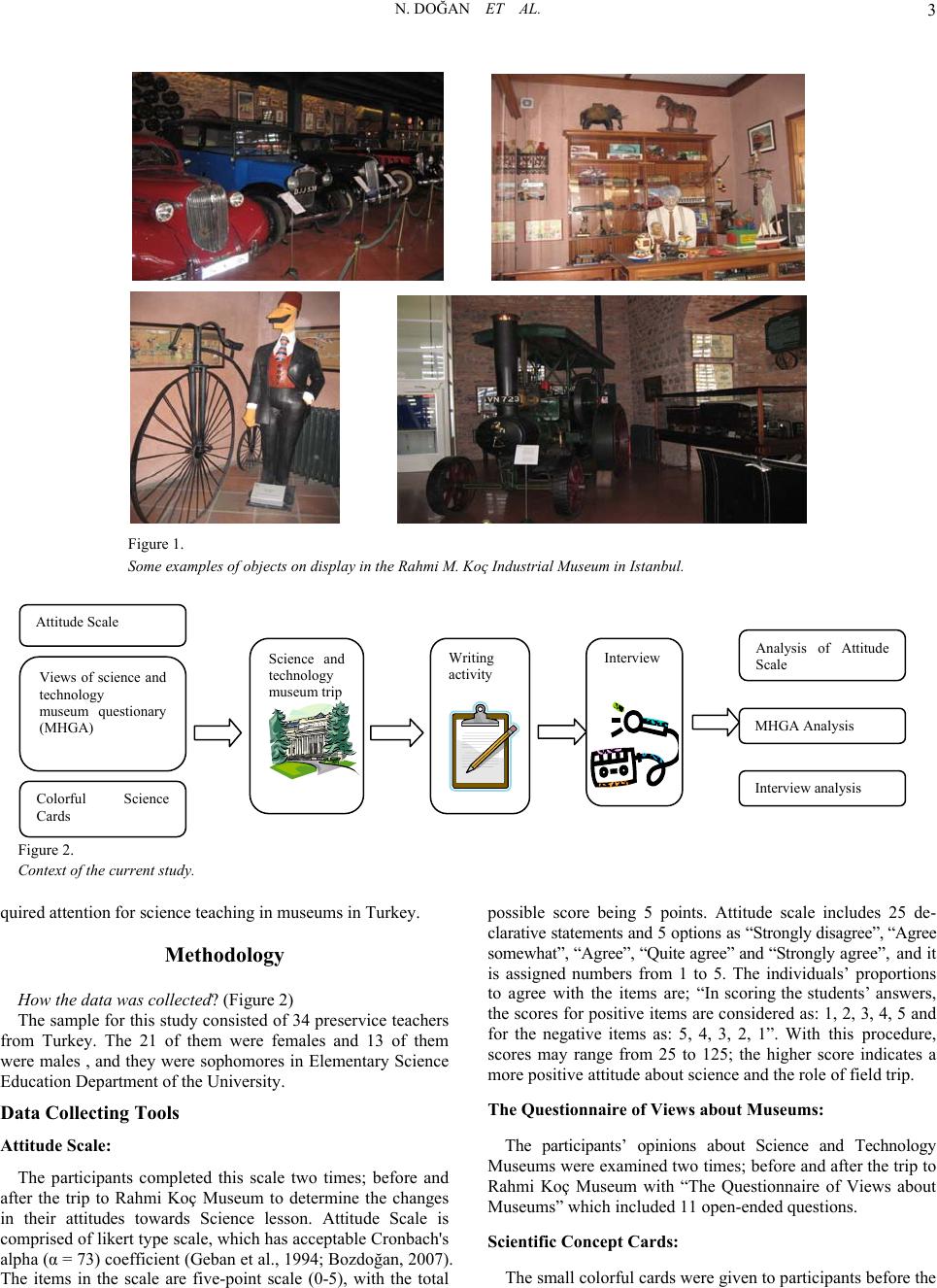

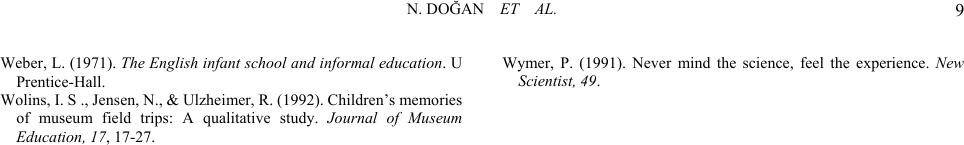

|