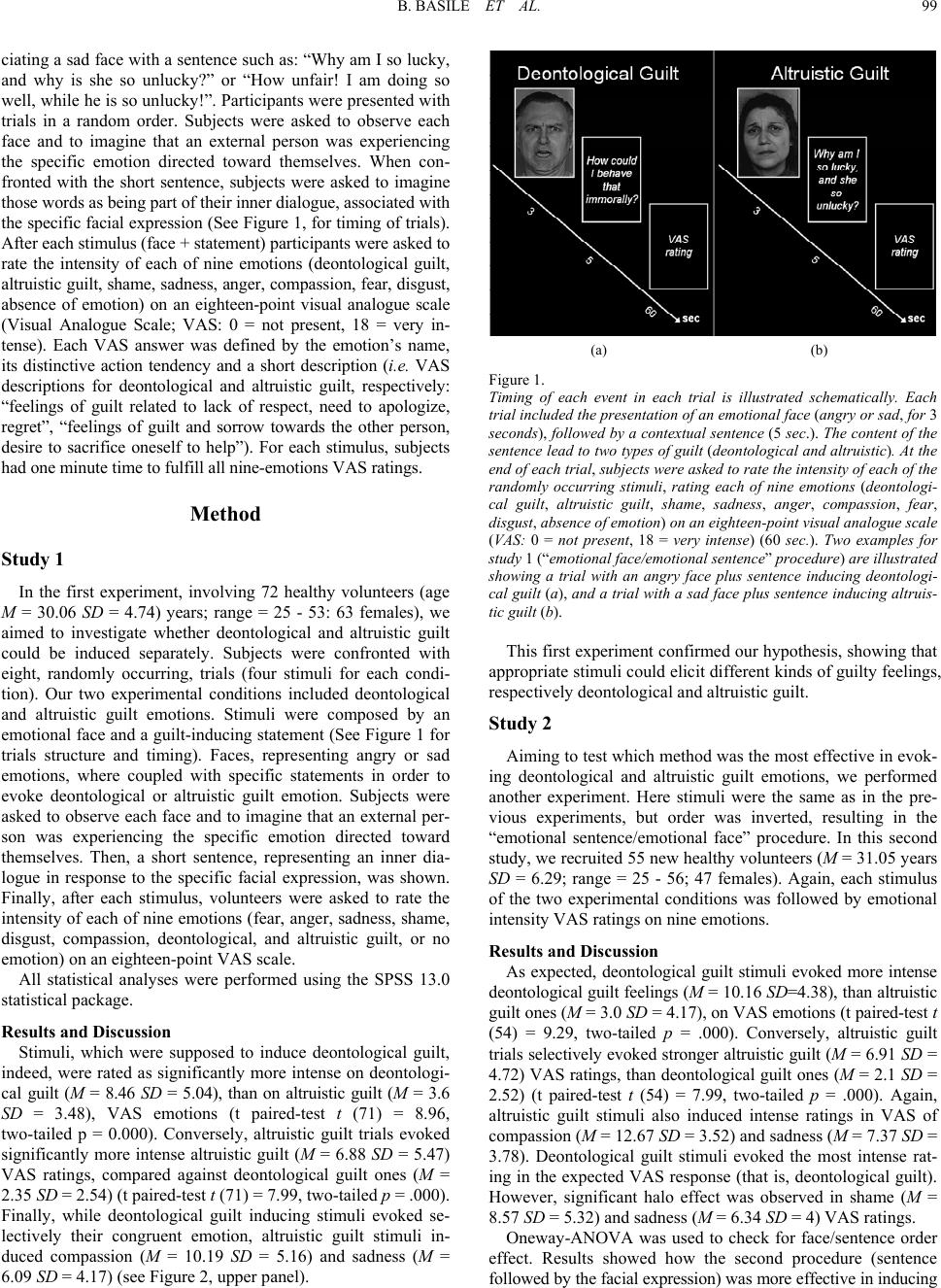

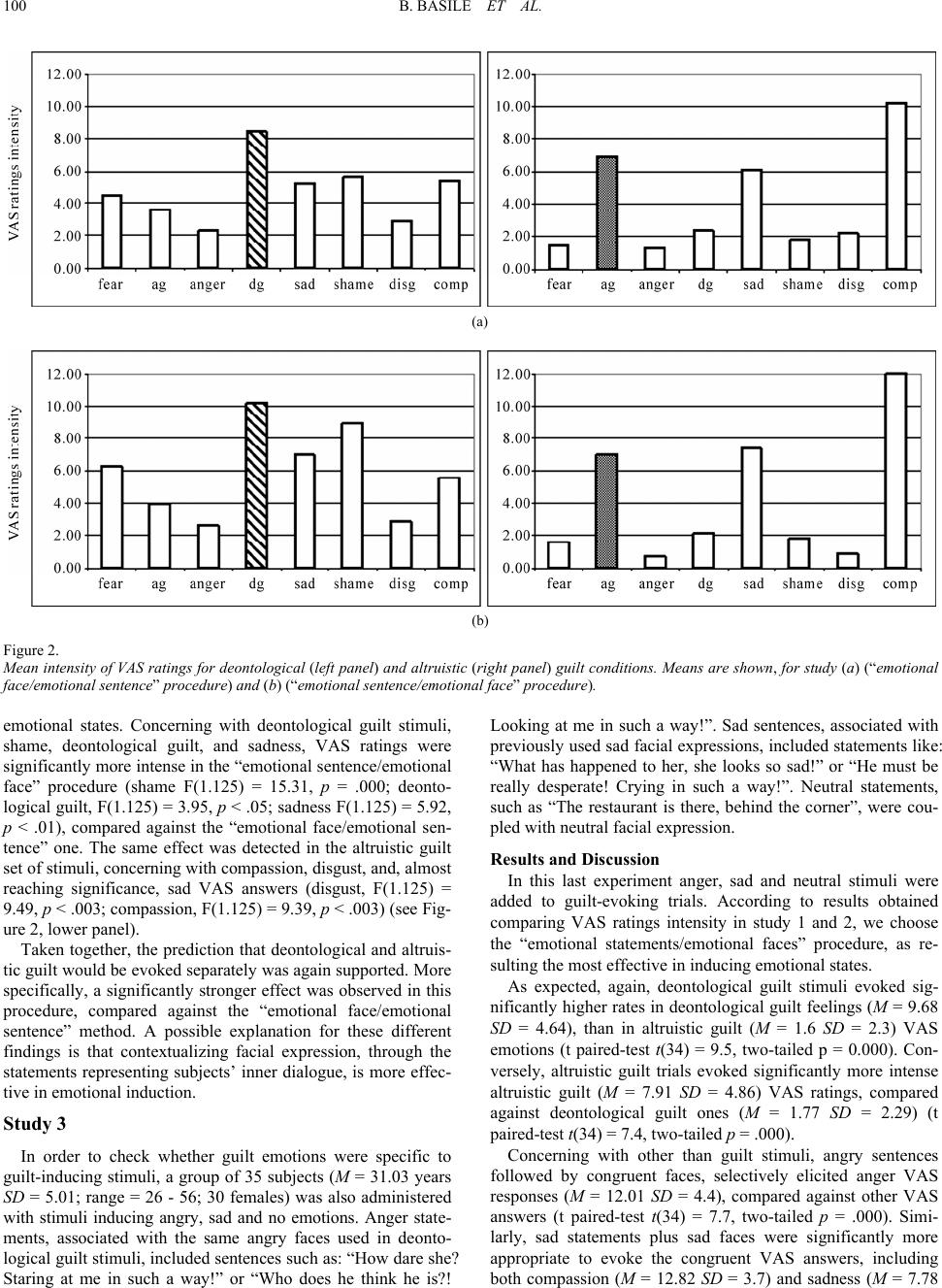

Psychology 2011. Vol.2, No.2, 98-102 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.22016 Eliciting Guilty Feelings: A Preliminary Study Differentiating Deontological and Altruistic Guilt Barbara Basile1,2, Francesco Mancini1 1School of Cognitive Psychotherapy, Italy; 2Neuroimaging Laboratory, Santa Lucia Foundation, IRCCS, Italy. Email: basile_barbara@yahoo.it Received October 26th, 2010; revised January 5th, 2011; accepted January 20th, 2011. Guilt has been identified as both an intrapsychic and an interpersonal emotion. The current study presents evi- dence of the existence of two senses of guilt, deontological and altruistic guilt, induced through different ex- perimental paradigms. Deontological guilt evolves from having slighted moral authority or norms, while altruis- tic guilt arises from selfish behavior and the distress of others. We hypothesize that specific stimuli would evoke, separately, deontological guilt and altruistic/interpersonal guilt feelings. Two different procedures were used to test our hypothesis, adding two emotions as control conditions (i.e. anger and sadness). Results clearly indicate that two different guilt emotions can be evoked separately, by appropriate stimulation. Findings and possible clinical implications are discussed. Keywords: Guilt, Deontological Guilt, Altruistic Guilt, Emotions Introduction We usually experience a feeling of guilt when we recognize ourselves as the cause of another person’s misfortune. However, beyond this main meaning, guilty feelings might arise in dif- ferent situations. Within psychological literature on guilt emo- tions, two main hypotheses have been identified: the intrapsy- chic (Izard, 1977; Lewis, 1971; Monteith, 1993; Mosher, 1965; Mosher, 1966; Piers & Singer, 1971; Wertheim & Schwartz, 1983) and the interpersonal perspective (Baumeister, Stillwell & Heatherton, 1994; Hoffman, 1981; Hoffman, 1987; Nieden- thal, Tangney & Gavanski, 1994; Tangney, 1999; Tangney & Dearing, 2002). The intrapsychic theory states the inner moral rules and val- ues we have learned and introjected since early stages of our lives, resulting in Freud so called “Super-Io”, one of the most fundamental structures of our psyche. According to this ap- proach, guilt represents the emotional result of a conflict be- tween our introjected moral authority rules and values, and our behaviours, or their omissions. Its evolutionary function is the respect of others’ rights and of authority. In this view, guilt concerns with the feeling of having disobeyed to one’s own inner moral values, even without really acting or sharing with others. This might cause an expectation of punishment, expia- tion or apologize. The person feeling guilty has the feeling of being a “bad person” (Lewis, 1971). The interpersonal theory posits that guilt results from the awareness of having caused unjustified harm to another or, in a more general sense, of not having behaved altruistically, thus resulting in selfish behavior. This feeling is based on empathy and compassion (Weiss, 1986). Within the interpersonal under- standing, guilt might arise simply by observing someone who has been unjustly penalized. More generally, interpersonal, or altruistic guilt, might derive from not having behaved altruisti- cally toward another person. Here, the trigger is the presence of a suffering person, being unjustly penalized by chance, we did not help, or not even tried to share his or her pain with others. The evolutionary function of altruistic guilt is to establish non-aggressive relationships and its aim is altruism (Baumeister, Stillwell, & Heatherton, 1994). According to this, the first aim of this article was to clear out this difference. A couple of experiments were also used to validate an appropriate set of stimuli for a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) paradigm (Ba sile, Mancini, Macaluso, Caltagirone, Frackowiak, & Bozzali, 2010). An additional goal achieves a methodological issue. Specifically, we aimed to test which, between two distinct emotional procedure s, was the most appropriate to evoke a complex emotion, such as guilt. Finally, we ran a third experiment in order to check whether guilt, and not other emotional stimuli, selectively evoked guilty feelings. Ac- cording to this purpose, in our third study, guilt stimuli were contrasted against other control emotions (that is, anger and sadness). We also expected both deontological and altruistic guilt being characterized by a specific emotional halo, further strengthening and characterizing their difference. We predict deontological guilt to be associated with emotions of shame and disgust, and altruistic guilt with compassion and sadness feel- ings. We will present three experiments, involving a total of 128 healthy volunteers. In all studies we used Ekman’s ‘Pictures of Facial Affect’ (Ekman & Friesen, 1976) depicting different emotional facial expressions (50% males and 50% females) coupled with specific sentences. Statements were matched by length and complexity, in order to control for eventual con- founding effects. Appropriate associations between faces and statements aimed to evoke deontological and altruistic guilt emotions. Typical target trials evoking deontological guilt were elicited by coupling an angry face with sentences like: “Oh my God! How could I do such a thing!?” or “How could I behave that immorally!”. Conversely, altruistic guilt was evoked asso-  B. BASILE ET AL. 99 ciating a sad face with a sentence such as: “Why am I so lucky, and why is she so unlucky?” or “How unfair! I am doing so well, while he is so unlucky!”. Participants were presented with trials in a random order. Subjects were asked to observe each face and to imagine that an external person was experiencing the specific emotion directed toward themselves. When con- fronted with the short sentence, subjects were asked to imagine those words as being part of their inner dialogue, associated with the specific facial expression (See Figure 1, for timing of trials). After each stimulus (face + statement) participants were asked to rate the intensity of each of nine emotions (deontological guilt, altruistic guilt, shame, sadness, anger, compassion, fear, disgust, absence of emotion) on an eighteen-point visual analogue scale (Visual Analogue Scale; VAS: 0 = not present, 18 = very in- tense). Each VAS answer was defined by the emotion’s name, its distinctive action tendency and a short description (i.e. VAS descriptions for deontological and altruistic guilt, respectively: “feelings of guilt related to lack of respect, need to apologize, regret”, “feelings of guilt and sorrow towards the other person, desire to sacrifice oneself to help”). For each stimulus, subjects had one minute time to fulfill all nine-em otions VAS ratings. Method Study 1 In the first experiment, involving 72 healthy volunteers (age M = 30.06 SD = 4.74) years; range = 25 - 53: 63 females), we aimed to investigate whether deontological and altruistic guilt could be induced separately. Subjects were confronted with eight, randomly occurring, trials (four stimuli for each condi- tion). Our two experimental conditions included deontological and altruistic guilt emotions. Stimuli were composed by an emotional face and a guilt-inducing statement (See Figure 1 for trials structure and timing). Faces, representing angry or sad emotions, where coupled with specific statements in order to evoke deontological or altruistic guilt emotion. Subjects were asked to observe each face and to imagine that an external per- son was experiencing the specific emotion directed toward themselves. Then, a short sentence, representing an inner dia- logue in response to the specific facial expression, was shown. Finally, after each stimulus, volunteers were asked to rate the intensity of each of nine emotions (fear, anger, sadness, shame, disgust, compassion, deontological, and altruistic guilt, or no emotion) on an eighteen-point VAS scale. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 13.0 statistical package. Results and Discussion Stimuli, which were supposed to induce deontological guilt, indeed, were rated as significantly more intense on deontologi- cal guilt (M = 8.46 SD = 5.04), than on altruistic guilt (M = 3.6 SD = 3.48), VAS emotions (t paired-test t (71) = 8.96, two-tailed p = 0.000). Conversely, altruistic guilt trials evoked significantly more intense altruistic guilt (M = 6.88 SD = 5.47) VAS ratings, compared against deontological guilt ones (M = 2.35 SD = 2.54) (t pai red-test t (71) = 7.99, two-tailed p = .000). Finally, while deontological guilt inducing stimuli evoked se- lectively their congruent emotion, altruistic guilt stimuli in- duced compassion (M = 10.19 SD = 5.16) and sadness (M = 6.09 SD = 4.17) (see Figure 2, upper panel). (a) (b) Figure 1. Timing of each event in each trial is illustrated schematically. Each trial included the presentation of an emotional face (angry or sad, for 3 seconds), followed by a contextual sentence (5 sec.). The content of the sentence lead to two types of guilt (deontological and altruistic). At the end of each trial, subjects were asked to rate the intensity of each of the randomly occurring stimuli, rating each of nine emotions (deontologi- cal guilt, altruistic guilt, shame, sadness, anger, compassion, fear, disgust, absence of emotion) on an eighteen-point visual analogue scale (VAS: 0 = not present, 18 = very intense) (60 sec.). Two examples for study 1 (“emotional face /emotional sentence” procedure) are illustrated showing a trial with an angry face plus sentence inducing deontologi- cal guilt (a), and a trial with a sad face plus sentence inducing altruis- tic guilt (b). This first experime nt confirme d our hypothesis, showing that appropriate stimuli could elicit different kinds of guilty feelings, respectively deontological and altruistic guilt. Study 2 Aiming to test which method was the most effective in evok- ing deontological and altruistic guilt emotions, we performed another experiment. Here stimuli were the same as in the pre- vious experiments, but order was inverted, resulting in the “emotional sentence/emotional face” procedure. In this second study, we recruited 55 new healthy volunteers (M = 31.05 years SD = 6.29; range = 25 - 56; 47 females). Again, each stimulus of the two experimental conditions was followed by emotional intensity VAS ratin g s on nine emotions. Results and Discussion As expected, deontological guilt stimuli evoked more intense deontological guilt feelings (M = 10.16 SD=4.38), than altruistic guilt ones (M = 3.0 SD = 4.17), on VAS emotions (t paired-test t (54) = 9.29, two-tailed p = .000). Conversely, altruistic guilt trials selectively evoked stronger altruistic guilt (M = 6.91 SD = 4.72) VAS ratings, than deontological guilt ones (M = 2.1 SD = 2.52) (t paired-test t (54) = 7.99, two-tailed p = .000). Again, altruistic guilt stimuli also induced intense ratings in VAS of compassion (M = 12.67 SD = 3.52) and sadness (M = 7.37 SD = 3.78). Deontological guilt stimuli evoked the most intense rat- ing in the expected VAS response (that is, deontological guilt). However, significant halo effect was observed in shame (M = 8.57 SD = 5.32) and sadness (M = 6.34 SD = 4) VAS ratings . Oneway-ANOVA was used to check for face/sentence order effect. Results showed how the second procedure (sentence followed by the facial expression)was more effective in inducing  B. BASILE ET AL. 100 (a) (b) Figure 2. Mean intensity of VAS ratings for deontological (left panel) and altruistic (right panel) guilt conditions. Means are shown, for study (a) (“emotional face/emotional sentence” procedure) and (b) (“emotional sentence/emotional face” procedure). emotional states. Concerning with deontological guilt stimuli, shame, deontological guilt, and sadness, VAS ratings were significantly more intense in the “emotional sentence/emotional face” procedure (shame F(1.125) = 15.31, p = .000; deonto- logical guilt, F(1.125) = 3.95, p < .05; sadness F(1.125) = 5.92, p < .01), compared against the “emotional face/emotional sen- tence” one. The same effect was detected in the altruistic guilt set of stimuli, concerning with compassion, disgust, and, almost reaching significance, sad VAS answers (disgust, F(1.125) = 9.49, p < .003; compassion, F(1.125) = 9.39, p < .003) (see Fig- ure 2, lower panel). Taken together, the prediction that deontological and altruis- tic guilt would be evoked separately was again supported. More specifically, a significantly stronger effect was observed in this procedure, compared against the “emotional face/emotional sentence” method. A possible explanation for these different findings is that contextualizing facial expression, through the statements representing subjects’ inner dialogue, is more effec- tive in emotional induction. Study 3 In order to check whether guilt emotions were specific to guilt-inducing stimuli, a group of 35 subjects (M = 31.03 years SD = 5.01; range = 26 - 56; 30 females) was also administered with stimuli inducing angry, sad and no emotions. Anger state- ments, associated with the same angry faces used in deonto- logical guilt stimuli, included sentences such as: “How dare she? Staring at me in such a way!” or “Who does he think he is?! Looking at me in such a way!”. Sad sentences, associated with previously used sad facial expressions, included statements like: “What has happened to her, she looks so sad!” or “He must be really desperate! Crying in such a way!”. Neutral statements, such as “The restaurant is there, behind the corner”, were cou- pled with neutral facial expression. Results and Discussion In this last experiment anger, sad and neutral stimuli were added to guilt-evoking trials. According to results obtained comparing VAS ratings intensity in study 1 and 2, we choose the “emotional statements/emotional faces” procedure, as re- sulting the most effective in inducing emotional states. As expected, again, deontological guilt stimuli evoked sig- nificantly higher rates in deontological guilt feelings (M = 9.68 SD = 4.64), than in altruistic guilt (M = 1.6 SD = 2.3) VAS emotions (t paired-test t(34) = 9.5, two-tailed p = 0.000). Con- versely, altruistic guilt trials evoked significantly more intense altruistic guilt (M = 7.91 SD = 4.86) VAS ratings, compared against deontological guilt ones (M = 1.77 SD = 2.29) (t paired-test t( 34) = 7.4, two-tailed p = .000). Concerning with other than guilt stimuli, angry sentences followed by congruent faces, selectively elicited anger VAS responses (M = 12.01 SD = 4.4), compared against other VAS answers (t paired-test t(34) = 7.7, two-tailed p = .000). Simi- larly, sad statements plus sad faces were significantly more appropriate to evoke the congruent VAS answers, including both compassion (M = 12.82 SD = 3.7) and sadness (M = 7.78  B. BASILE ET AL. 101 SD = 4.11). Sad stimuli elicited significantly more intense compassion, than sadness VAS ratings (t paired-test t(34) = 8.35, two-tailed p = .000). Neutral stimuli did not evoke any significant emotion in VAS ratings, all reaching approximately zero. The last study confirmed that specific guilt-inducing stimuli, and not other emotional stimuli, selectively evoked the hy- pothized guilty feelings. Finally, across all experiments, spe- cifically in the second one, a halo effect was observed. Intense shame VAS ratings (M = 8.5 SD = 5.3) were reported when subjects were confronted with deontological guilt stimuli, while compassion (M = 12.6 SD = 3.4) and sadness (M = 7.31 SD = 3.7) were associated with altruistic guilt stimuli. General Discussion The purpose of the present study was to investigate whether deontological and altruistic guilt could be induced separately, through appropriate stimuli (facial expressions and content- specific statements). We aimed to investigate whether guilt emotions could be differentiated on the basis of an intrapsychic (deontological guilt) and an interpersonal (altruistic guilt) per- spective. Indeed, our three experiments showed evidence of different guilt expressions, which might be evoked separately. We showed how the appropriate association between specific statements and congruent facial expressions selectively elicited different types of guilt. In the first two studies different emo- tional induction procedures were used. In the first one, facial expressions were followed by deontological or altruistic state- ments, while in the second, and most effective, procedure sen- tences were shown first, followed by facial expressions. Finally, in the last study, two other set of emotional stimuli (represent- ing angry and sad emotions), and an additional neutral one, were introduced in order to confirm the specific selective effect of guilt and other-than-guilt emotional responses. Moreover, each type of guilt seemed to be characterized by a specific emotional halo. More specifically, feelings of deonto- logical guilt seemed to be associated with shame, but not dis- gust, as expected (Miller, 1997) and, to a lesser extent, sadness. On the other hand, altruistic guilt, as enclosing more interper- sonal emotions, was associated with intense feelings of com- passion and sadness. These results emphasize the negative va- lence of guilt related emotions, and represent clear evidence of a common underlying substrate involving suffering toward one-self and toward others, the latter being more intense when experiencing altruistic guilt feelings (Tilghman-Osborne, Cole, & Felton, 2010). Commonly, guilt has been considered as a pro-social emo- tion, promoting constructive and proactive pursuits, leading to reparative and more emphatic behavior ( Lewis, 1971; Monteith, 1993; Tangney, Stuewig, & Mashek, 2007). This main goal is evident in altruistic guilt and, to less extend, in deontological guilt, which has shown to be associated with feelings of shame. Although shame has been defined as a moral emotion (Frank, 1988; Ketelaar, 2004; Smith, 1759) very closely related to guilt, there is growing evidence that they are clearly distinguishable (Tangney, 1991; Tangney, 1995; Tangney, 1995; Tangney, 1996; De Hooge, Zeelenberg, & Breugelmans, 2007). Guilt and shame share some common characteristics, but might be dis- tinguished on the basis of their public-private dimension, their action tendencies (hiding and escaping in shame, and confess- ing, apologizing or undoing the consequences of the behavior in guilt) and on their intensity (shame being described as more painful and intense) (Lewis, 1971; Tangney& Dearing, 2002; Tangney, Stuewig, & Mashek, 2007). Our results support previous literature suggesting a distinc- tion between an intrapsychic and an interpersonal guilty feeling. While deontological guilt is a self-directed and inner feeling, which does not require an external agent, altruistic guilt needs an external cause (i.e. another person) to be elicited. In conclu- sion, our study supports the view of different kinds of guilty feelings, each characterized by specific goals, thoughts, and action tendencies (Roseman, Wiest, & Swartz, 1994). Our findings could have also interesting clinical implications. Previous studies have demonstrated that both depressed and obsessive patients are sensitive specifically to interpersonal guilt (Esherick, M., O’Connor, L. E., Berry, J. W., & Weiss, 1999; O’Connor, Berry, Weiss, & Gilbert, 2002), which would correspond to our altruistic guilt. By contrast, Mancini (2008) has recently suggested that obsessive- compulsi ve pati ents c ould be selectively sensitive to deontological guilt, and not to altru- istic, or interpersonal, guilt. In fact, Lopatcka, Rachman (Lo- patka & Rachman, 1995) and Shafran (Shafran, 1997) have demonstrated that obsessives’ concern over a harmful event, for instance, a gas explosion, was drastically reduced if responsibility for the event was transferred to someone else (i.e. the psycho- therapist). According to this data, obsessive patients’ concern is not for the victims, but for self-reproach or another’s reproach for having violated a moral norm, like prudence. Moreover, as clinical observations suggest, obsessive patients are frequently concerned about sins. For instance, a religious or sexual nature, even though no harm is caused to anyone, and obsessions and compulsions are aimed to control or prevent them. Our study has several limitations. In the three samples, fe- males were over-represented, and participants were quite young and also influenced by Catholic culture. It is, thus, possible that our results may not be generalized to a broader population. Similar studies should be replicated including males and older populations. Additionally, a similar procedure might be used on clinical populations including patients with obsessive- compul- sive or depressed patients. References Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. S., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin, 1 1 5 , 243-267. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.243 Basile B., Mancini F., Macaluso E., Caltagirone C., Frackowiak R. S., & Bozzali M. (2011). Deontological and altruistic guilt: Evidence for distinct neurobiological substrates. Human Brain Mapping, 32, 229- 239. De Hooge, I. E., Zeelenberg, M. & Breugelmans, S. M. (2007). Moral sentiments and cooperation: Differential influences of shame and guilt. Cognition & Emotion, 21, 1025 -1042. doi:10.1080/02699930600980874 Ekman, P. & Friesen, W. V. (1976). Pictures of Facial Affect. Palo Alto: Consulting. Esherick, M., O’Connor, L. E., Berry, J. W., & Weiss, J. (1999, Un- published). The role of guilt in obsessions and compulsions. Frank, R.H. (1988). Passions within reason: The strategic role of the emotions. New York: Norton. Hoffman, M. L. (1981). Is altruism part of human nature? Journal of  B. BASILE ET AL. 102 Personality and Social Psychology, 40, 121-137. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.40.1.121 Hoffman, M. L. (1987). The contribution of empathy to justice and moral judgment. In N. Eisenberg and J. Strayer (Eds.), Empathy and its development (pp. 47-80). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Izard, C. E. (1977). Hum an Emotions. New York: Plenum Press. Ketelaar, T. (2004). Ancestral emotions, current decisions: Using evo- lutionary game theory to explore the role of emotions in deci- sion-making. In C. Crawford & C. Salmon (Eds.), Evolutionary psy- chology, public policy and personal decisions (pp. 145-163). Mah- wah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc. Lewis, H. B. (1971). Shame and guilt in neurosis. New York: Interna- tional Universities Press. Lopatka, C. & Rachman, S. (1995). Perceived responsibility and com- pulsive checking: an experimental analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 673-684. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(94)00089-3 Mosher, D. L. (1965). Interaction of fear and guilt in inhibiting unac- ceptable behavior. Journal of Co n sulting Psychology, 29, 161-167. doi:10.1037/h0021748 Mosher, D. L. (1966). The development and multitrait-multimethod analysis of three measures of three aspects of guilt. Journal of Con- sulting Psychology, 30, 25-29. doi:10.1037/h0022905 Monteith, M. J. (1993). Self-regulation of stereotypical responses: Im- plications for progress in prejudice reduction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 469-485. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.3.469 Miller, W. I. (1997). The anatomy of disgust. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Mancini, F. (2008). I sensi di colpa altruistico e deontologico. Cogni- tivismo Clinico, 5, 123-144. Niedenthal, P. M., Tangney, J. P., & Gavanski, I. (1994). “If only I weren’t” versus “If only I hadn’t”: Distinguishing shame and guilt in conterfactual thinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 585-595. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.585 O’Connor, L. E., Berry, J. W., Weiss, J., & Gilbert, P. (2002). Guilt, fear, submission, and empathy in depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 71, 19-27. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00408-6 Piers, G. & Singer, M. (1971). Shame and Guilt: A Psychoanalytic and Cultural Study. New York: Norton. Roseman, I. J., Wiest, C. & Swartz, T. S. (1994). Phenomenology, Behaviors, and Goals Differentiate Discrete Emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 206-221. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.206 Smith, A. (1759). The theor y of moral sentiments. London: A. Miller. Shafran, R. (1997). The manipulation of responsibility in obsessive- compulsive di sorde r. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36, 397- 407. Tangney, J. P. (1999). The self-conscious emotions: Shame, guilt, em- barrassment and pride. In T. Dalgleish and M. J. Power (Eds.), Hand- book of cognition and emotion (pp. 541-568). New York: John Wiley & Sons. Tangney, J. P. & Dearing, R. L. (2002). Shame and guilt. New York: Guilford Press. Tilghman-Osborne C., Cole, D. A., & Felton, J. W. (2010). Definition and measurement of guilt: Implications for clinical research and practice. Clinical and Psychological Review, 30, 536-546. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.007 Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review o f Psychology, 58, 345-72. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070145 Tangney, J. P. (1991). Moral affect: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Journal of Personality a nd Social Psychology, 61, 598-607. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.598 Tangney, J. P. (1995). Recent empirical advances in the study of shame and guilt. American Behavioural S c i ence, 38, 1132- 45. doi:10.1177/0002764295038008008 Tangney, J. P. (1995). Shame and guilt in interpersonal relationships. In J. P. Tangney and K. W. Fischer (Eds.), Self-Conscious Emotions: The Psychology of Shame, Guilt, Embarrassment, and Pride (pp. 114-390). New York: Guilford. Tangney, J. P. (1996). Conceptual and methodological issues in the assessment of shame and guilt. Behavioural Research and Therapy, 34, 741-54. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(96)00034-4 Wertheim, E. H. & Schwartz, J. C. (1983). Depression, guilt, and self-management of pleasant and unpleasant events. Journal of Per- sonality and Social Psychology, 45, 884-889. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.45.4.884 Weiss, J. (1986). Unconscious guilt. In J. Weiss and H. Sampson (Eds.), The psychoanalytic process: Theory, clinical observation and em- pirical research (pp. 43-67). New York: Guilford Press.

|