Psychology 2011. Vol.2, No.2, 78-84 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.22013 The Influence of Social and Individual Variables on Ethnic Attitudes in Guatemala Brien K. Ashdown1, Judith L. Gibbons2, Jana Hackathorn2, Richard D. Harvey2 1Department of Psychology, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, Alaska, USA; 2Saint Louis University, St. Louis, Missouri, USA. Email: bashdown@alaska.edu, {gibbonsjl, jhackath, harveyr}@slu.edu Received November 20th, 2010; revised January 12th, 2011; accepted January 27th, 2011. Ethnic attitudes may be a consequence of both group membership, as posited by Social Identity Theory (SIT), and of individual difference characteristics, as posited by Social Dominance Theory. University students in Guatemala (N = 196) reported their ethnic identity and completed a battery of surveys including Social Domi- nance Orientation (SDO), social distance, gender role attitudes, and social desirability scales. Results indicated that similar ethnicity, low SDO, close social distance and egalitarian gender role attitudes accurately predicted positive attitudes toward the Indigenous group. Similar ethnicity, close social distance, and high social desirabil- ity predicted positive attitudes toward the super-ordinate (Ladino) group. These results imply that many factors affect attitudes toward ethnic groups, such as SDO, gender role attitudes and social desirability. These results have implications for theories of inter-group relations and also for potential interventions to improve ethnic rela- tions in Guatemala. Keywords: Social Identity Theory, Social Dominance Orientation, Ethnic Attitudes, Guatemala Introduction Social Identity Theory (SIT) is among the many social cog- nition paradigms that provide explanations for prejudice and group bias (Tajfel, 1981; Turner & Reynolds, 2001). Specifi- cally, it posits that individuals form opinions of others based upon their group membership. That is, people have a more fa- vorable view toward members of their own group (called the in-group) and a less favorable view toward members of other groups (out-groups). This is true even for arbitrarily formed groups that serve no functional purpose, such as those created in a laboratory (Tajfel, 1981; Bigler, Brown, & Markell, 2001). Other research has implicated individual differences, or per- sonality variables, in prejudice and group bias, such as a Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994). Ekehammar and Akrami have suggested that, in reality, neither sociological factors, like SIT, nor individual factors, like SDO, alone can account for all of the variance in prejudiced beliefs. Instead, they suggest that a combination of sociological and individual factors lead to biased attitudes (Ak- rami & Ekehammar, 2003). This issue is particularly interesting in societies such as Gua- temala. In Guatemala, distinction is made between the indige- nous Mayan people and Ladinos, or those with European heri- tage. This distinction continues to cause discrimination against the Indigenous people. This situation in Guatemala is particu- larly relevant to the current research for two main reasons: first, the relative fluidity of ethnic identification in Guatemala (Little, 2004); and second, the distinction between the dominant La- dinos and minority Indigenous people is based on power (e.g., financial, governmental, educational) and not population num- bers (Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo Hu- mano, 2005). Because of these two reasons, Guatemala is an ideal place to begin exploring the impact of individual factors and social factors on ethnic prejudice and discrimination. Social Identity Theory Social Identity Theory posits that individuals identify them- selves as members of a group and then, in order to enhance their self-identity, evaluate and treat their group favorably and other groups (and their members) less favorably (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). This is true not only of ethnic groups, but also arbitrarily formed groups, such as school children assigned to groups differentiated and identified solely by shirt color (Bigler, Brown, & Markell, 2001). If one follows the logic of Social Identity Theory that in-group sympathies will often lead to out-group derogation, then preju- dice, racism, and discrimination can be explained in terms of simple group dynamics. However, the link between in-group identification and out-group derogation is not universal or in- evitable, in that merely identifying with a group does not nec- essarily lead to prejudiced attitudes (Aboud, 1988). Allport stated that individuals could prefer their in-group without feel- ing hostility toward out-groups (Allport, 1958). While there are situations where high levels of in-group favoritism could be directly related to out-group derogation, this type of direct rela- tionship is not automatic or universal. For example, Gibson interviewed more than three thousand South African participants about groups with which they did and did not identify and the strength of those identifications. Participants were then asked questions regarding interracial and political tolerance. Gibson found that individuals could main- tain strong in-group identities without political or racial intol- erance. In other words, strong group identification (with racial groups, language groups, etc.) did not impede strong identifica- tion with the national group, even though the national group  B. K. ASHDOWN ET AL. 79 contained members of various out-groups. The greatest predic- tor of political intolerance was group threat, and the greatest predictor of racial intolerance was a lack of inter-group contact, not simply group identification (Gibson, 2006). This indicates that while group membership is an important ingredient for discriminatory behavior, it alone is not sufficient. Other aspects of inter-group behavior, such as personality and individual differences, may also be crucial components. Social Dominance Orientation Social Dominance Theory contends that societies - through such factors as prejudiced attitudes, social roles, culturally spe- cific beliefs, and discriminatory behavior - create ideologies that support and maintain group hierarchies (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994). Dominant groups hold a dispropor- tionate amount of power and trappings associated with their status, such as money and housing. Conversely, minority groups are laden with a disproportionate amount of undesir- ables such as lower economic status, poorer health, and higher instances of criminal prosecution and punishment (Pratto, et al., 2000). Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) - a significant factor in Social Dominance Theory - is an individual difference variable that describes an attitude relevant to intergroup relations (Pratto et al., 1994). SDO is most commonly defined as support or preference for hierarchical group structures and the belief that social groups do and should differ in value. Simply stated, it is the extent to which an individual desires and accepts that one group is superior to another (Ekehammar & Akrami, 2003). People who endorse hierarchical relations between groups (high SDO) are more likely to support ideologies that legitimize group inequality and one group’s justified superiority while people low in SDO tend to strongly support ideologies that attenuate group inequality (Pratto et al., 2000). SDO is a sig- nificant factor in biased and prejudiced attitudes (Pratto et al., 2000), generalized prejudice (Ekehammar et al., 2004) and cultural elitism (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994). Furthermore, men have higher SDO than women (Pratto, Si- danius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994) and people from Latin America tend to have higher SDO than people born in other parts of the world (Sidanius, Pratto, & Bobo, 1994). As SDO is not based on any specific foundation for inequal- ity (such as biblical or racial inferiority theories), any cultural belief or ideology that suggests there is a hierarchical difference between groups should theoretically correlate with scores on a SDO measuree, Existing cross-cultural research has shown that SDT is applicable across cultures because group-enhancing with-attenuating ideologies, while culturally specific, can be found in almost all societies (Pratto et al., 1994; Pratto et al., 2000). It is unlikely that SDO (or other individual difference vari- ables) alone causes group prejudice (Pratto et al., 1994). It is likely the combination of individual difference variables such as SDO and sociological variables such as group identification as explained by Social Identity Theory that best explains preju- diced group relations (Ekehammar & Akrami, 2003). The cur- rent study attempts to explore the combined effect of SDO and ethnic group identification, as well as other social attitudes and demographic variables, in Guatemala. Guatemalan Cultural S tructure and Hierarchies Inequality and discrimination have been a part of life in Gua- temala since the Spanish conquistadores first arrived in the 1500s. Distinctions were made between the native Mayan peo- ple and those with Spanish blood. This ethnic distinction, which led to the discrimination and oppression of Indigenous persons, continues (Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo Humano, 2005). In Guatemala today, there are two major ethnic groups: those who claim Mayan heritage and are known as Indigenous people and the Ladinos, who are usually defined as people with mixed heritage and seen as non-Indigenous. This distinction has led to the continuing discrimination of the In- digenous people of Guatemala (Gibbons & Ashdown, 2010). Great disparities exist for the Indigenous people in education, health, and capital (Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo Humano, 2005). In the 1996 peace accord that ended 36 years of civil war defined by much violence towards the Mayan Indigenous people, provisions were included that called for equality for Indigenous people (Comas-Díaz, Lykes, & Alarcón, 1998). However, the government has been slow to implement those changes, as Indigenous persons in Guatemala still lag behind Ladinos in health, capital, and education (Pro- grama de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo Humano, 2005). Bias and discrimination are also apparent in social attitudes. Children of the Quiché (an Indigenous group of the Guatemalan highlands) viewed being Indigenous as undesirable. When asked what it meant to be Quiché, 57% answered negatively and 18% claimed that they did not like being Indigenous. When asked the question “Why would someone not like being a Quiché?” a typical answer was “When they go to the [Ladino] town and return, they are ashamed to be Indígenas [Indige- nous]” (Quintana & Segura-Herrera, 2003). In Antigua, Guatemala (a major tourist venue/city), hundreds of Mayans make a living by hawking their weavings and handi- crafts to tourists. However, even though the Mayans play an important role in supporting tourism in the city, one female vendor said in an interview, “Some people are afraid to speak [a Mayan dialect] because the Ladinos don’t like it. They only want Spanish. The girls, they don’t want to weave because they want to be modern. They want to dress like Americans” (Little, 2004). Clearly, ethnic identification and group membership play important and sometimes unfortunate roles in the everyday lives of Guatemalans, both Indigenous persons and Ladinos, as well as strongly influence biased ethnic attitudes and discrimi- nation (Ashdown & Gibbons, 2010). Guatemala lends itself as a unique society in which to ex- plore prejudice and biased attitudes for two reasons. First, eth- nic identification is relatively fluid in Guatemala (Little, 2004). Individuals are able to successfully transition from one group to another (usually from an Indigenous identification to a Ladino identification) simply by doing such things as speaking a dif- ferent language (Spanish), wearing Western or non-Indigenous clothing, and associating with the “correct” groups of people. This is relevant in the context of societal influences of group bias, such as Social Identity Theory. If people are able to move from one ethnic group to another, their group identification could be less important to them because of a sense of imper- manence. Alternatively, it might make their group identification even more important to them, as they could view it as some-  B. K. ASHDOWN ET AL. 80 thing fluid and fleeting that they have to work toward main- taining. Second, the difference between the majority group (Ladinos) and the minority group (Indigenous) is one of power and not one of numbers. Ladinos comprise about 58% of the population, and Indigenous Maya persons comprise approximately 40%. The remainder is accounted for by groups such as the Xinca, which do not readily fit into either category (Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo Humano, 2005). Because of these demographics, one might hypothesize that SDO would be high among Ladinos as they might see a society with unequal group hierarchies based on ideology as the only way they can maintain power and control over such a large “minority.” Con- versely, SDO could be low among Indigenous people because they might belief that the unequal group hierarchies holding them back are not based on numerical superiority but on ideol- ogy. Current Research The current study explored the predictive influences of indi- vidual and social variables on ethnic group bias. We hypothe- sized that SDO is related to positive ethnic attitudes toward Ladinos (the dominant group in Guatemala) and negative atti- tudes toward Indigenous persons (the minority group in Gua- temala). We also hypothesized that ethnic group identification and SDO would predict ethnic attitudes, both independently and in conjunction with one another. Finally, we explored how ethnic group identification and SDO influence group bias in the presence of other variables that have been previously linked to group bias (i.e., gender (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994), social desirability (Katz & Hass, 1988), and social dis- tance (Byrnes & Kiger, 1988)) in order to determine the unique impact of these variables. Method Participants Participants (N = 196; 61.2% female) in Guatemala were re- cruited from both private Catholic (n = 136) and public (n = 60) universities in order to increase diversity and representativeness. In order to further ensure representativeness, the sample from the private university was recruited from a meeting of students who had gathered from satellite campuses scattered across Guatemala, and the public university sample was recruited from a region with a high Indigenous population. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 52 (M = 25.77, SD = 6.41). The mean amount of post-secondary education was 4.1 years (SD = 3.2). Measures Ethnic Identification Participants marked a point on a 15 cm line to indicate their ethnicity. The end points of the line were anchored with “pure Indigenous” and “pure Ladino/a.” The participants’ marks were then measured from the left, meaning that higher numbers (or marks farther from the left) indicate a claim to more Ladino (or less Indigenous) heritage. Social Dominance Orientation SDO was measured using the Social Dominance Orientation Scale (Pratto et al., 1994). Participants used a 7-point Likert scale (very negative to very positive) to demonstrate their feel- ings toward statements such as “It’s probably a good thing that certain groups are at the top and other groups are at the bot- tom.” Higher scores indicated a higher espousal of social dominance. Ethnic Attitudes Ethnic attitudes were measured using the 23-item Attitudes toward Indigenous Persons of Guatemala scale (AIG) and the 14-item Attitudes toward Ladino Persons of Guatemala scale (ALG) developed by Gibbons and Ashdown (2010). Both scales have shown acceptable initial reliability, with the AIG having a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84, and the ALG an alpha of 0.79 (Gibbons & Ashdown, 2010). All participants responded to both scales, regardless of ethnicity. Participants used a 4-point Likert scale (1 being strongly agree to 4 being strongly disagree) to respond to items such as, “Indigenous children should not wear their traditional clothing to school” on the AIG and, “In general, Ladinos are well-mannered” on the ALG. Positively worded items were reverse-scored so that higher values represented more positive attitudes toward each group. Attitudes toward Gender Roles Because gender differences in levels of SDO have been re- ported (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994), egalitarian attitudes toward gender roles were measured using a combina- tion of the twelve-item Attitudes toward Women Scale for Adolescents (AWSA; (Galambos, Petersen, Richards, & Gitel- son, 1985)) and the eight-item Attitudes toward Male Roles Scale (MRAS; (Pleck, Sonenstein, & Ku, 1994)). Participants used a 4-point Likert scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) to respond to statements such as “Swearing is worse for a girl than a boy” on the AWSA and “A guy will lose respect if he talks about his problems” on the MRAS. Higher scores on the combined scale indicated more egalitarian views toward gender roles. Social Distance Social distance, or the degree of comfort that people feel in the presence of out-group members, has been related to group bias in previous research (Byrnes & Kiger, 1988). In this study, social distance was measured using a modified version of Byrnes and Kiger’s (1988) scale. Each participant completed two versions of the social distance scale. One measured social distance from Indigenous persons, and one measured social distance from Ladino persons. Other than the target group, the scales were identical. Participants used a 7-point Likert scale (very uncomfortable to very comfortable) to respond to eight statements such as “I believe I would be happy to have an In- digenous (Ladino) person as my personal physician.” Lower scores indicated a desire for more social distance from the tar- get group. Social Desirability Social desirability is the phenomenon of people responding to research tools in ways that they believe are socially accept- able, which may not always indicate their true beliefs or atti- tudes. In past research, higher levels of social desirability have been related to more positive attitudes toward out-groups (Katz & Hass, 1988). In this study, social desirability was measured using the impression management subscale of the Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding (BIDR; (Paulhus, 1984))  B. K. ASHDOWN ET AL. 81 Participants used a 7-point Likert scale (not true to very true) to respond to 20 statements such as “When I hear people talking privately, I avoid listening.” Higher scores indicated more so- cially desirable responding. Demographics Participants were asked to provide demographic material, such as age, gender, level of education, and ethnicity. Procedure Potential participants were informed of the voluntary and anonymous nature of participation via a recruitment letter. The battery of surveys took approximately 45 minutes to complete. To be sensitive to the time constraints of the institutions, pro- fessors or meeting organizers were allowed to use their discre- tion as to whether the questionnaire packets were administered in classrooms, during university meetings, or sent home with students to be returned during the following class session. Results In order to measure the reliability of the measures, we com- puted Cronbach’s alphas for each scale. The Cronbach’s alphas for the AIG (0.84), the ALG (0.70), the SDO scale (0.77), the attitudes toward gender roles scale (0.68), and the BIDR (0.71) were acceptable, demonstrating that the measures performed reliably in Guatemala. In addition, we computed correlations among the variables, which can be found in Table 1. To test the hypothesis that Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) would be related to ethnic attitudes, respective Pearson’s correla- tions were computed between the participants’ SDO and their scores on the AIG and ALG. SDO was significantly and nega- tively correlated with scores on the AIG (r = – .391, p < .001), meaning that the greater the individuals’ SDO, the less positive attitudes they had toward Indigenous persons. The correlation between SDO and the ALG was not significant (r = –0.144, p = 0.073). This pattern of a significant and negative relationship between SDO and the AIG was also found when we computed the correlations separately for each ethnic group. To test the hypothesis that ethnic identification and SDO would both independently and conjointly influence ethnic atti- tudes, as well as to explore these variables’ influences on ethnic attitudes in the presence of other variables previously linked to group attitudes, we computed two hierarchical regression mod- els with the AIG and ALG as dependent variables, respectively. In each model, variables were added in blocks. Each block was tested to determine if it significantly predicted the dependent variable and if it increased the model’s predictive ability in conjunction with the previously added blocks. First, we computed a four-block hierarchical regression model for predicting scores on the AIG (see Table 2). In block one, the demographic variables of age, gender (male = 1, fe- male = 2), years of post-secondary education and the type of sample (1 = public university, 2 = private university) were added to the model. In block two, attitudes toward gender roles, social distance from indigenous persons, and social desirability were added. Ethnicity as a continuous variable (higher numbers indicating a claim to more Ladino heritage) was added as block three, and SDO as block four. Each block in the model signifi- cantly predicted scores on the AIG. In addition, each block increased the model’s predicting power and adjusted R2. The final model (i.e., with all four blocks) was significant (F(9,120) = 14.175, p < .001). Within the final model, attending a private university (ß = .301, p < .001), more years of higher education (ß = .143, p = .038), less social distance from Indigenous per- sons (ß = .241, p < .01), more egalitarian attitudes toward gen- der roles (ß = .161, p = .02), higher indigenous ethnicity (ß = – .325, p < .001), and low SDO (ß = – .291, p < .001) all uniquely predicted more positive attitudes toward Indigenous persons and accounted for 47.9% of the variance in those Table 1. Zero-order correlat ions. Age Gender Education EthnicityGender RolesBIDR SDI SDL AIG ALG SDO Age –0.132 0.131 –0.125 –0.001 0.018 –0.158* –0.117 –0.025 –0.129 0.142 Gender − 0.024 0.039 0.146* 0.048 –0.035 0.032 –0.100 0.067 –0.096 Education − − –0.010 0.007 0.160*–0.100 –0.056 0.045 –0.060 –0.050 Ethnicity − − − –0.016 0.226**–0.207**0.519***–0.326*** 0.383***0.008 Gender Roles − − − − 0.093 0.061 0.024 0.334*** 0.072 –0.299*** BIDR − − − − − 0.076 0.029 0.116 0.194* –0.123 SDI − − − − − − 0.053 0.401*** –0.045 –0.142 SDL − − − − − − − –0.241** 0.357***0.152 AIG − − − − − − − − –0.131 –0.391*** ALG − − − − − − − − − –0.144 SDO − − − − − − − − − − Note. Male = 1, Female = 2; Education = number of years of higher education; Ethnicity (higher numbers indicate a claim to more Ladino and less Indigenous heritage); Gender Roles = attitudes toward gender roles (higher scores indicate more egalitarian views); BIDR = Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responses (higher scores indicate more desirable responding); SDI = Social distance desired from Indigenous people (higher scores indicate less social distance); SDL = Social distance desired from Ladino people (higher scores indicate less social distance); AIG = Attitudes toward Indigenous persons (higher scores indicate more positive attitudes); ALG = Attitudes toward Ladino persons (higher scores indicate more positive attitudes); SDO = Social Dominance Orientation (higher scores indicated higher social dominance orientation). p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. *  B. K. ASHDOWN ET AL. 82 Table 2. Attitudes toward indigenou s people. Variables Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 4 Demographics Age 0.068 0.106 0.064 0.086 Gender –0.136 –0.144 –0.095 –0.124 Education 0.160 0.183* 0.163* 0.143* Sample 0.301*** 0.282*** 0.338*** 0.313*** Social Attitudes Gender roles 0.260** 0.248*** 0.161* Social Distance 0.367*** 0.276*** 0.241*** BIDR 0.076 0.132 0.115 Ethnicity –0.332*** –0.325*** Social Dominance –0.291*** F 4.535** 9.430*** 12.049*** 14.175*** Adjusted R2 0.099 0.314 0.407 0.479 ∆R2 0.127 0.224 0.092 0.072 ∆F 4.535** 14.061*** 20.067** 17.799*** Note. Standardized scores are reported. Male = 1, Female = 2; Sample - Public University = 1, Private University = 2; Gender Roles = attitudes toward gender roles (higher scores indicate more egalitarian views); Social Distance = distance desired from Indigenous persons (higher scores indicate less social distance); BIDR = Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responses (higher scores indicate more desirable responding); Ethnicity (higher numbers indicate a claim to more Ladino and less Indigenous heritage); Social Dominance (higher scores indicated higher social dominance orientation). *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. attitudes. In addition to this significant model, a fifth block was attempted where the interaction between SDO and ethnicity was added to explore the relationship between these to vari- ables. However, this fifth step was not significant, and did not add to the final model’s predictive ability. Next we computed a 4-block hierarchical regression model for predicting scores on the ALG (see Table 3). Variables were added in blocks in the same order as the model for the AIG. While the final model (i.e., with all four blocks) was significant (F(9,136) = 4.34, p < .001), blocks one and four were not. In other words, adding SDO to the previous three blocks did not in- crease the final model’s predictive power or adjusted R2. In the final significant model, less social distance from Ladinos (ß = .196, p = .038), endorsing more socially desirable behaviors (ß = .16, p = .051) and higher Ladino ethnicity (ß = .253, p = .007) all uniquely predicted positive attitudes toward Ladino persons and accounted for 18.1% of the variance in those attitudes. As in the model for the AIG, a fifth block was attempted where the interaction between SDO and ethnicity was added to explore the relationship between these to variables. As before, this fifth block was not significant, and did not add to the overall model. Discussion Ethnic identification significantly predicted ethnic attitudes, as suggested by Social Identity Theory (Tajfel, 1981). Ladinos and people claiming a mixed heritage had less positive views toward Indigenous persons, and Indigenous individuals had less positive attitudes toward Ladinos. Table 3. Attitudes toward ladino peopl e. Variables Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 4 Demographics Age –0.091 –0.071 –0.072 –0.04 Gender 0.074 0.002 0.008 0.003 Education –0.047 –0.061 –0.058 –0.066 Sample –0.001 0.002 –0.009 –0.025 Social Attitudes Gender roles 0.069 0.093 0.055 Social Distance 0.291** 0.163 0.196* BIDR 0.230** 0.178* 0.161* Ethnicity 0.259** 0.253** Social Dominance –0.151 F 0.607 3.726*** 4.414*** 4.340*** Adjusted R2 –0.012 0.123 0.167 0.181 ∆R2 0.018 0.150 0.048 0.019 ∆F 0.607 7.761*** 7.843** 3.153 Note. Standardized scores are reported. Male = 1, Female = 2; Sample - Public University = 1, Private University = 2; Gender Roles = attitudes toward gender roles (higher scores indicate more egalitarian views); Social Distance = distance desired from Indigenous persons (higher scores indicate less social distance); BIDR = Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responses (higher scores indicate more desirable responding); Ethnicity (higher numbers indicate a claim to more Ladino and less Indigenous heritage); Social Dominance (higher scores indicated higher social dominance orientation). *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) was negatively associ- ated with attitudes toward Indigenous people. Individuals with higher SDO - those who support unequal group hierarchies - held more negative attitudes toward the subordinate Indigenous group. This is in agreement with previous findings (Pratto, et al., 2000), where higher levels of SDO were related to negative attitudes toward culturally specific minority groups. However, the results did not support the previous finding (Pratto, et al., 2000) that higher SDO is related to positive attitudes toward the majority group. Instead, the relationship between SDO and attitudes toward the super-ordinate group was not statistically significant. This could be due to the similar size of the super-ordinate and subordinate groups in Guatemala. Ladinos may have higher levels of SDO and less positive views of Indigenous people because they realize that the unequal group hierarchies they espouse - what allows them to maintain their power and control - are dependent upon ideology and numerical superiority. In- digenous people, on the other hand, are low in SDO because they recognize that those ideologies, and not a numerically larger super-ordinate group, are responsible for their subordi- nate position in Guatemalan society. For Indigenous people in Guatemala, high SDO might mean an acceptance of the status quo and the dominance of Ladinos. The hierarchical regression models revealed that multiple variables predict ethnic attitudes. In the model predicting atti- tudes toward Indigenous people, type of university attended, more higher education, social distance from Indigenous people, attitudes toward gender roles, and ethnic identification were all significant independent predictors of attitudes toward Indige-  B. K. ASHDOWN ET AL. 83 nous people. Together, these five variables accounted for nearly 50% of the variance in attitudes toward Indigenous people in Guatemala. A diverse variety of constructs appear to influence ethnic attitudes, making the relationship more complex than one explained by group identification or SDO. For example, individuals with more egalitarian views about gender roles also had more positive attitudes toward Indigenous people. It is not surprising that people who espouse more equality between the genders would also espouse more equality between ethnic groups and have a more favorable view of the minority group. People who desired less social distance from Indigenous individuals (in other words, those claiming to be more comfortable in the company of Indigenous people) had more positive attitudes towards them. Again this is not surpris- ing, though it is interesting to ponder the relationship between those variables. The question of whether holding positive atti- tudes toward Indigenous people make the participants more comfortable in their presence, or if being comfortable in the presence of Indigenous people leads to more positive attitudes toward them is left unanswered by this data. Participants who attended a private university had more posi- tive attitudes toward Indigenous people (but not toward Ladino people). This is probably explained by the demographics of the sample from the private university. The majority of the private university sample was recruited at a university-sponsored re- gional event specifically designed for Indigenous students - thus a large number of these students were of Indigenous heri- tage. And as indicated by previous research (Turner & Rey- nolds, 2001) and the current research, individuals tend to have more positive attitudes toward their in-group. It is interesting to note, however, that the type of university participants attended predicted attitudes toward Indigenous people even when ethnic- ity was controlled in the regression, indicating that there is something about attending a private university that contributes to the model above and beyond simple ethnic identification (the inverse is also true). This could be due to a variety of reasons (for example, socioeconomic status) that future research could explore. Ethnic identification and SDO independently contributed to individuals’ attitudes toward Indigenous persons. People claim- ing more Indigenous heritage had more positive attitudes to- ward Indigenous people, as one would expect based on Social Identity Theory. Those with higher SDO had more negative attitudes toward Indigenous persons (the culturally-specific subordinate ethnic group). However, the interaction between ethnic identification and SDO did not account for any addi- tional variance in attitudes toward Indigenous people. This suggests that ethnic identification and social dominance may be working in separate capacities as they influence group attitudes and not in conjunction with one another. In the model predicting attitudes toward Ladinos, only social distance, ethnicity, and socially desirable responding signifi- cantly predicted attitudes toward Ladinos, and together ac- counted for only 19% of the variance in those attitudes. Not surprisingly, those who claim to be more comfortable in the presence of Ladinos and those claiming more Ladino heritage have more positive attitudes toward Ladino people. Social desirability functioned in a fashion different from what is usually seen in prejudice research in North American studies (Katz & Hass, 1988). It is interesting that people who responded in a more socially desirable manner on the BIDR held more positive attitudes toward Ladinos. In the United States, overt negativity, prejudice, and discrimination toward a minority group is seen as undesirable or unacceptable. Conse- quently, ethnic majority group members usually respond in a socially desirable manner when asked about members of ethnic minority groups (Katz & Hass, 1988). In Guatemala, people responded in a more socially desirable manner when asked their feelings about the majority group. Perhaps because Ladinos hold so much power and wealth in Guatemala, people are more careful about what they say about Ladinos for fear of possible consequences and retribution. There are various limitations to this study. For example, in Guatemala, college students are an elite section of the popula- tion. Guatemala is still striving toward providing universal primary and secondary education. Since Indigenous persons in Guatemala generally receive less formal education than La- dinos, only the especially talented or moderately wealthy In- digenous students are able to pursue a college education (Pro- grama de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo Humano, 2005). Additionally, while we were able to account for a large and statistically significant portion of the variance in ethnic atti- tudes (especially toward Indigenous people), the majority of that variance remains unexplained. Future research should fo- cus on additional individual difference or group personality variables, such as collective self-esteem. As suggested earlier, it is likely that it is a combination of societal and individual vari- ables that leads to group bias (Ekehammar & Akrami, 2003). Finally, ethnic identification, or self-labeling, is only a small part of the overarching construct of ethnicity. Further examin- ing the intricacies and complexities of ethnic identity will im- prove predictive models of ethnic attitudes. Oversimplifying prejudiced attitudes not only inhibits our understanding and knowledge about those attitudes, but it also inhibits our ability to develop meaningful and successful plans for eliminating them. The current study is one more step in exploring the relationship among ethnic group identification, individual difference variables, intergroup contact, and ethnic attitudes. It provides more information regarding the nature of ethnic group bias and prejudice while demonstrating the com- plexity of ethnic attitudes. Further investigations of prejudice and discrimination, using creative and complex measures, will help expose and clarify the complicated relationships among the constructs that influence ethnic attitudes. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Guillermina Herrera, Lisette Rodríquez, Carlos Rafael Yllescas Mijangos, María Mercedes Valdés, Claire T. Van den Broeck, Ana Gabriela González, María del Pilar Grazioso, and Walter E. Little for help during various stages of this study. References Aboud, F. E. (1988). Children and prejudice. Oxford: Basil Blackwell Inc. Allport, G. W. (1958). The nature of prejudice. New York: Doubleday Anchor Books.  B. K. ASHDOWN ET AL. 84 Bigler, R. S., Brown, C. S., and Markell, M. (2001, July-August). When Groups are not created equal: Effects of group status on the format of intergroup attitudes on children. Child Development, 72, 1151-1162. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00339 Byrnes, D. A., & Kiger, G. (1988, Spring). Contemporary measures of attitudes toward blacks. Education and Psychological Measurement, 48, 107-118. doi:10.1177/001316448804800113 Comas-Díaz, L., Lykes, M. B., and Alarcón, R. D. (1998, July). Ethnic conflict and the psychology of liberation in Guatemala, Peru, and Puerto Rico. American Psycho lo g is t, 53, 778-792. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.53.7.778 Ekehammar, B., & Akrami, N. (2003, October). The relation between personality and prejudice: A variable- and a person-centered ap- proach. European Journal of Personality, 17, 449-464. doi:10.1002/per.494 Ekehammar, B., Akrami, N., Gylje, M., & Zakrisson, I. (2004, Sep- tember/October). What matters most to prejudice: Big five personal- ity, social dominance orientation or right-wing authoritarianism? European Journal o f P e r s o n al i t y , 1 8, 463-482. doi:10.1002/per.526 Galambos, N. L., Petersen, A. C., Richards, M., & Gitelson, I. B. (1985, September). The attitudes toward women scale for adolescents (AWSA): A study of reliability and validity. Sex Roles, 13, 343-356. Gibbons, J. L., & Ashdown, B. K. (2010, June). Ethnic identification, attitudes, and group relations in Guatemala. Psychology, 1, 116-127. doi:10.4236/psych.2010.12016 Gibson, J. L. (2006, October). Do strong group identities fuel intoler- ance? Evidence from the South African case. Political Psychology, 27, 665-705. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2006.00528.x Katz, I., & Hass, R. G. (1988, December). Racial ambivalence and american value conflict: Correlational and priming studies of dual cognitive structures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 893-905. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.55.6.893 Little, W. (2004, February) Outside of social movements: Dilemmas of indigenous handicrafts vendors in Guatemala. American Ethnologist, 31, 43-59. doi:10.1525/ae.2004.31.1.43 Paulhus, D. L. (1984, March). Two-component models of socially desirable responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 598-609. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.46.3.598 Pleck, J. H., Sonenstein, F. L., and Ku, L. C. (1994, April). Attitudes toward male roles among adolescent males: A discriminant validity analysis. Sex Roles, 30, 481-501. doi:10.1007/BF01420798 Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994, Octo- ber). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psy- chology, 67, 741-763. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.741 Pratto, F., Liu, J. H., Levin, S., Sidanius, J., Shih, M., Bachrach, H., & Hegarty, P. (2000, May). Social dominance orientation and the le- gitimization of inequality across cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31, 369-409. doi:10.1177/0022022100031003005 Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo Humano (2005). Diversidad Etnico-Cultural: La Ciudadanía en un Estado. Informe Nacional de Desarrollo Humano, United Nations System. Quintana, S. M., & Segura-Herrera, T. A. (2003, October) Develop- ment transformations of self and identity in the context of oppression. Self and Identity, 2, 269-285. doi:10.1080/714050248 Sidanius, J., Pratto, F., & Bobo, L. (1994, December). Social domi- nance orientation and the political psychology of gender: A case of invariance? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 998- 1011. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.998 Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of inter- group behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7-24). Chicago: Nelson Hall. Turner, J. C., & Reynolds, K. J. (2001). The social identity perspective in intergroup relations: Theories, themes, and controversies. In R. Brown & S. L. Gaertner (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psy- chology (pp. 133-152). Blackwell: Intergroup Processes.

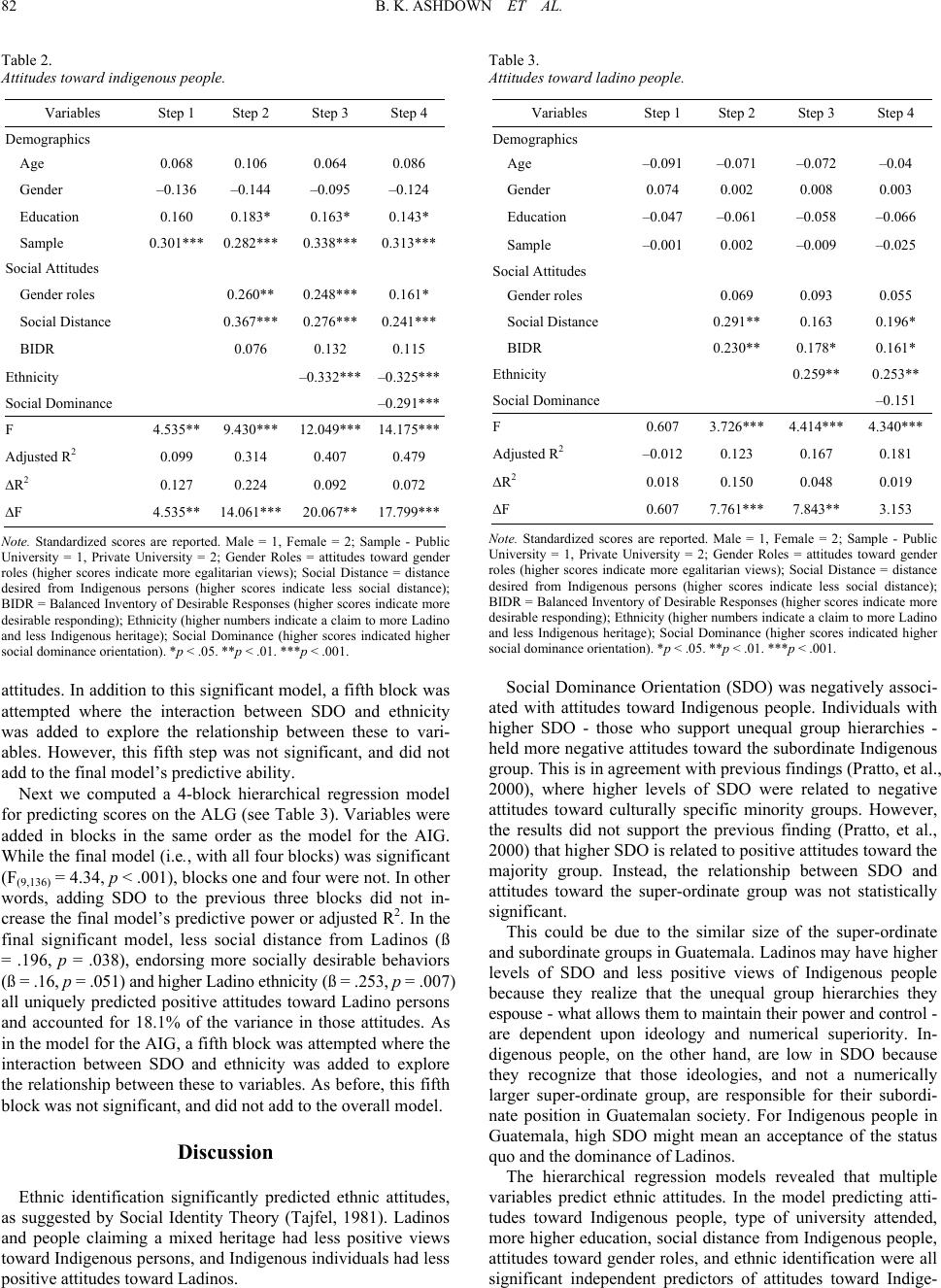

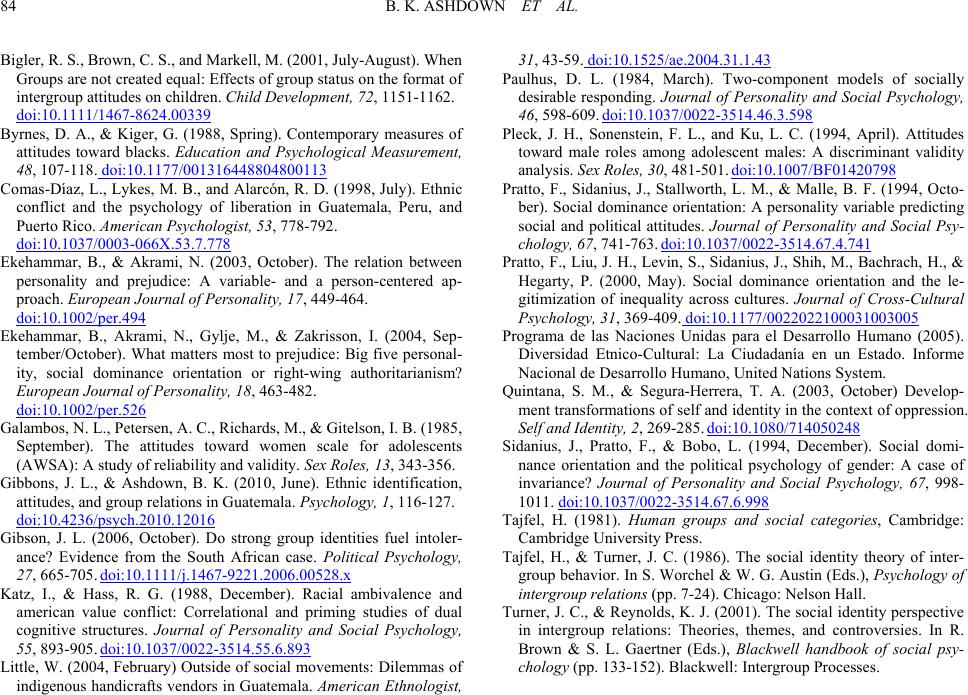

|