Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

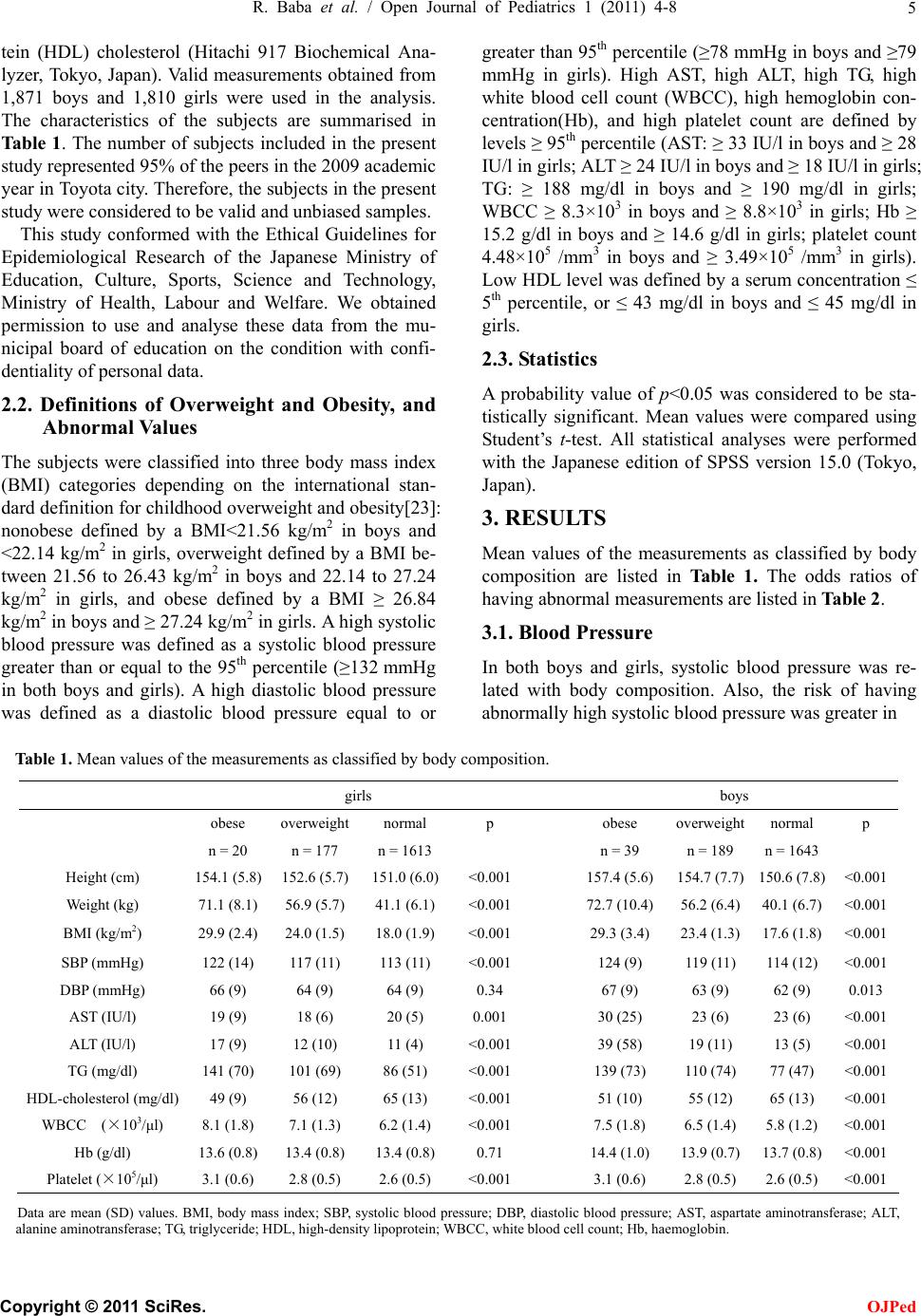

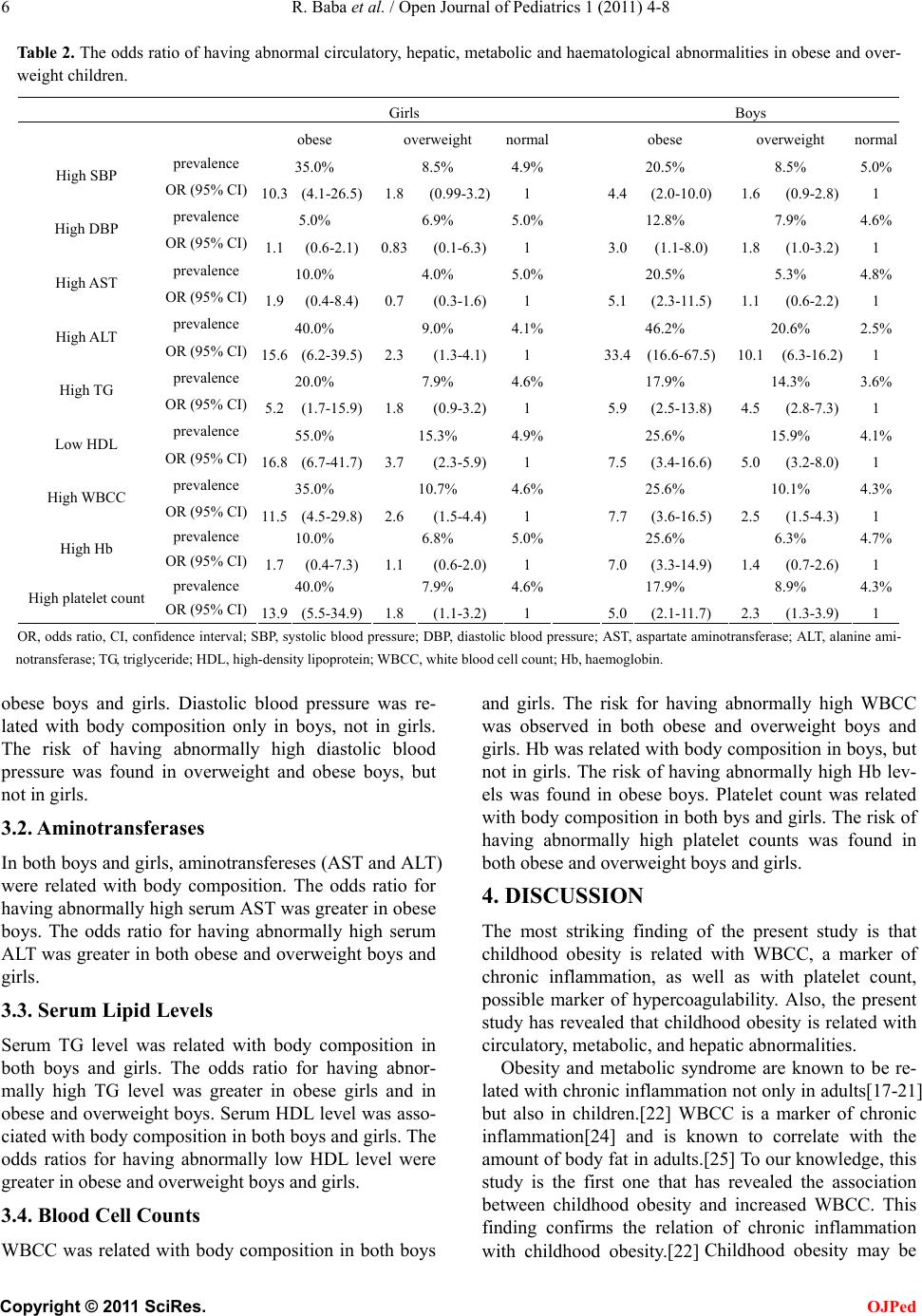

Open Journal of Pediatrics, 2011, 1, 4-8 doi:10.4236/ojped.2011.11002 Published Online March 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/OJPed/ OJPed ). Published Online March 2011 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPed Chronic Low-grade Inflammation and Haematological, Circulatory, Metabolic, and Hepatic Abnormalities in Childhood Obesity Reizo Baba, M.D., Osaaki Ando, M.D. Reizo Baba, M.D., Ph.D.1,2, Kyoko Shinohara, M.D.,3 Osaaki Ando, M.D., Ph.D.1, Jun Tanaka, M.D., Ph.D.1 1Committee for Health Promotion, Board of Education, Toyota City. 2Department of Neonatal and Perinatal Medicine, Aichi Medical University 3Department of Paediatrics, Ikeda Municipal Hospital. E-mail : babar@aichi-med-u.ac.jp ABSTRACT Background: Little is known as to the associations between childhood obesity and chronic low-grade inflammation, circulatory, hepatic, metabolic and haematological abnormalities. Methods and Results: A total of 1,871 boys and 1,810 girls were measured anthropometric data, white blood cell (WBCC), platelet count, blood pressure, plasma concentrations of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine ami- notransferase (ALT), triglyceride (TG), and high- density (HDL) lipoprotein cholesterol,. The subjects were classified into three body mass index categories depending on the international standard definition for child overweight and obesity. WBCC, platelet counts, systolic blood pressure, serum levels of ami- notransferases,TG and HDL-cholesterol were related with body composition in both boys and girls. Obese girls had high risks of having abnormal levels of WBCC, platelet count, systolic blood pressure (SBP), ALT, TG, HDL-cholesterol. Obese boys had high risks of having abnormal levels of WBCC, haemobo- bin concentration, platelet count, SBP, diastolic blood pressure, AST, ALT, TG, and HDL-cholesterol. Con- clusions: Childhood obesity is related with chronic inflammation, hypercoagulability, as well as circula- tory, metabolic, and hepatic abnormalities. Keywords: Obesity; Metabolic Syndrome; Inflammation; Platelet; Children 1. INTRODUCTION The prevalence of childhood obesity and metabolic syn- drome are increasing in the western countries[1-5] as well as in Asia.[6-8] These conditions are known to be associated with hypertension,[10-12] abnormal lipid and glucose metabolism,[10] liver dysfunction,[13-16] chronic low-grade inflammation[17,18] and hyperco- agulability[19-21] in the adult populations. However, little is known as to the association of obesity and these abnormalities in the paediatric populations.[22] There- fore, we aimed to investigate whether childhood obesity is related with these circulatory, metabolic and hepatic abnormalities, as well as with chronic low-grade in- flammation. 2. METHODS 2.1. Study Subjects and Measurements The subjects in the present study were all first-year jun- ior high school students who had been admitted to Toy- ota municipal public junior high schools in the 2009 academic year. Their mean age is 12.5(SD = 0.3) years old in both boys and girls. We utilized the database of the results of the medical checkups performed by us and possessed by Toyota Municipal Board of Education. Information that could be used to identify individual subjects had been deleted before the Board of Education had provided us with the data. At the medical check-up, experienced nurses meas- ured the subject’s body weight to the nearest 0.1 kg and height to the nearest 0.1 cm. Blood pressure was meas- ured with an automatic oscillometric sphygmomanome- ter (BP-103iII, Colin, Nagoya, Japan) after the student had been resting on a chair for more than 5 minutes. A second measurement was performed 2 minutes later, and the lower of the two measurements was used in the analysis. After an overnight fast, blood samples (6ml) were drawn from the peripheral veins for the measure- ments of complete blood cell counts, plasma concentra- tions of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine ami- notransferase (ALT), triglyceride, high-density lipopro-  R. Baba et al. / Open Journal of Pediatrics 1 (2011) 4-8 5 tein (HDL) cholesterol (Hitachi 917 Biochemical Ana- lyzer, Tokyo, Japan). Valid measurements obtained from 1,871 boys and 1,810 girls were used in the analysis. The characteristics of the subjects are summarised in Table 1. The number of subjects included in the present study represented 95% of the peers in the 2009 academic year in Toyota city. Therefore, the subjects in the present study were considered to be valid and unbiased samples. This study conformed with the Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Research of the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. We obtained permission to use and analyse these data from the mu- nicipal board of education on the condition with confi- dentiality of personal data. 2.2. Definitions of Overweight and Obesity, and Abnormal Values The subjects were classified into three body mass index (BMI) categories depending on the international stan- dard definition for childhood overweight and obesity[23]: nonobese defined by a BMI<21.56 kg/m2 in boys and <22.14 kg/m2 in girls, overweight defined by a BMI be- tween 21.56 to 26.43 kg/m2 in boys and 22.14 to 27.24 kg/m2 in girls, and obese defined by a BMI ≥ 26.84 kg/m2 in boys and ≥ 27.24 kg/m2 in girls. A high systolic blood pressure was defined as a systolic blood pressure greater than or equal to the 95th percentile (≥132 mmHg in both boys and girls). A high diastolic blood pressure was defined as a diastolic blood pressure equal to or greater than 95th percentile (≥78 mmHg in boys and ≥79 mmHg in girls). High AST, high ALT, high TG, high white blood cell count (WBCC), high hemoglobin con- centration(Hb), and high platelet count are defined by levels ≥ 95th percentile (AST: ≥ 33 IU/l in boys and ≥ 28 IU/l in girls; ALT ≥ 24 IU/l in boys and ≥ 18 IU/l in girls; TG: ≥ 188 mg/dl in boys and ≥ 190 mg/dl in girls; WBCC ≥ 8.3×103 in boys and ≥ 8.8×103 in girls; Hb ≥ 15.2 g/dl in boys and ≥ 14.6 g/dl in girls; platelet count 4.48×105 /mm3 in boys and ≥ 3.49×105 /mm3 in girls). Low HDL level was defined by a serum concentration ≤ 5th percentile, or ≤ 43 mg/dl in boys and ≤ 45 mg/dl in girls. 2.3. Statistics A probability value of p<0.05 was considered to be sta- tistically significant. Mean values were compared using Student’s t-test. All statistical analyses were performed with the Japanese edition of SPSS version 15.0 (Tokyo, Japan). 3. RESULTS Mean values of the measurements as classified by body composition are listed in Table 1. The odds ratios of having abnormal measurements are listed in Table 2. 3.1. Blood Pressure In both boys and girls, systolic blood pressure was re- lated with body composition. Also, the risk of having abnormally high systolic blood pressure was greater in Table 1. Mean values of the measurements as classified by body composition. girls boys obese overweight normal p obese overweight normal p n = 20 n = 177 n = 1613 n = 39 n = 189 n = 1643 Height (cm) 154.1 (5.8) 152.6 (5.7) 151.0 (6.0)<0.001 157.4 (5.6) 154.7 (7.7) 150.6 (7.8) <0.001 Weight (kg) 71.1 (8.1) 56.9 (5.7) 41.1 (6.1) <0.001 72.7 (10.4) 56.2 (6.4) 40.1 (6.7) <0.001 BMI (kg/m2) 29.9 (2.4) 24.0 (1.5) 18.0 (1.9) <0.001 29.3 (3.4) 23.4 (1.3) 17.6 (1.8) <0.001 SBP (mmHg) 122 (14) 117 (11) 113 (11) <0.001 124 (9) 119 (11) 114 (12) <0.001 DBP (mmHg) 66 (9) 64 (9) 64 (9) 0.34 67 (9) 63 (9) 62 (9) 0.013 AST (IU/l) 19 (9) 18 (6) 20 (5) 0.001 30 (25) 23 (6) 23 (6) <0.001 ALT (IU/l) 17 (9) 12 (10) 11 (4) <0.001 39 (58) 19 (11) 13 (5) <0.001 TG (mg/dl) 141 (70) 101 (69) 86 (51) <0.001 139 (73) 110 (74) 77 (47) <0.001 HDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) 49 (9) 56 (12) 65 (13) <0.001 51 (10) 55 (12) 65 (13) <0.001 WBCC (×103/μl) 8.1 (1.8) 7.1 (1.3) 6.2 (1.4) <0.001 7.5 (1.8) 6.5 (1.4) 5.8 (1.2) <0.001 Hb (g/dl) 13.6 (0.8) 13.4 (0.8) 13.4 (0.8) 0.71 14.4 (1.0) 13.9 (0.7) 13.7 (0.8) <0.001 Platelet (×105/μl) 3.1 (0.6) 2.8 (0.5) 2.6 (0.5) <0.001 3.1 (0.6) 2.8 (0.5) 2.6 (0.5) <0.001 Data are mean (SD) values. BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; TG, triglyceride; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; WBCC, white blood cell count; Hb, haemoglobin. C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPed  6 R. Baba et al. / Open Journal of Pediatrics 1 (2011) 4-8 Table 2. The odds ratio of having abnormal circulatory, hepatic, metabolic and haematological abnormalities in obese and over- weight children. Girls Boys obese overweight normal obese overweight normal prevalence 35.0% 8.5% 4.9% 20.5% 8.5% 5.0% High SBP OR (95% CI) 10.3 (4.1-26.5)1.8 (0.99-3.2)1 4.4 (2.0-10.0) 1.6 (0.9-2.8)1 prevalence 5.0% 6.9% 5.0% 12.8% 7.9% 4.6% High DBP OR (95% CI) 1.1 (0.6-2.1) 0.83(0.1-6.3) 1 3.0 (1.1-8.0) 1.8 (1.0-3.2)1 prevalence 10.0% 4.0% 5.0% 20.5% 5.3% 4.8% High AST OR (95% CI) 1.9 (0.4-8.4) 0.7(0.3-1.6) 1 5.1(2.3-11.5) 1.1 (0.6-2.2)1 prevalence 40.0% 9.0% 4.1% 46.2% 20.6% 2.5% High ALT OR (95% CI) 15.6 (6.2-39.5)2.3(1.3-4.1) 1 33.4(16.6-67.5) 10.1 (6.3-16.2)1 prevalence 20.0% 7.9% 4.6% 17.9% 14.3% 3.6% High TG OR (95% CI) 5.2 (1.7-15.9)1.8(0.9-3.2) 1 5.9(2.5-13.8) 4.5 (2.8-7.3)1 prevalence 55.0% 15.3% 4.9% 25.6% 15.9% 4.1% Low HDL OR (95% CI) 16.8 (6.7-41.7)3.7(2.3-5.9) 1 7.5(3.4-16.6) 5.0 (3.2-8.0)1 prevalence 35.0% 10.7% 4.6% 25.6% 10.1% 4.3% High WBCC OR (95% CI) 11.5 (4.5-29.8)2.6(1.5-4.4) 1 7.7(3.6-16.5) 2.5 (1.5-4.3)1 prevalence 10.0% 6.8% 5.0% 25.6% 6.3% 4.7% High Hb OR (95% CI) 1.7 (0.4-7.3) 1.1(0.6-2.0) 1 7.0 (3.3-14.9) 1.4 (0.7-2.6)1 prevalence 40.0% 7.9% 4.6% 17.9% 8.9% 4.3% High platelet count OR (95% CI) 13.9 (5.5-34.9)1.8(1.1-3.2) 1 5.0 (2.1-11.7) 2.3 (1.3-3.9)1 OR, odds ratio, CI, confidence interval; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine ami- notransferase; TG, triglyceride; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; WBCC, white blood cell count; Hb, haemoglobin. obese boys and girls. Diastolic blood pressure was re- lated with body composition only in boys, not in girls. The risk of having abnormally high diastolic blood pressure was found in overweight and obese boys, but not in girls. 3.2. Aminotransferases In both boys and girls, aminotransfereses (AST and ALT) were related with body composition. The odds ratio for having abnormally high serum AST was greater in obese boys. The odds ratio for having abnormally high serum ALT was greater in both obese and overweight boys and girls. 3.3. Serum Lipid Levels Serum TG level was related with body composition in both boys and girls. The odds ratio for having abnor- mally high TG level was greater in obese girls and in obese and overweight boys. Serum HDL level was asso- ciated with body composition in both boys and girls. The odds ratios for having abnormally low HDL level were greater in obese and overweight boys and girls. 3.4. Blood Cell Counts WBCC was related with body composition in both boys and girls. The risk for having abnormally high WBCC was observed in both obese and overweight boys and girls. Hb was related with body composition in boys, but not in girls. The risk of having abnormally high Hb lev- els was found in obese boys. Platelet count was related with body composition in both bys and girls. The risk of having abnormally high platelet counts was found in both obese and overweight boys and girls. 4. DISCUSSION The most striking finding of the present study is that childhood obesity is related with WBCC, a marker of chronic inflammation, as well as with platelet count, possible marker of hypercoagulability. Also, the present study has revealed that childhood obesity is related with circulatory, metabolic, and hepatic abnormalities. Obesity and metabolic syndrome are known to be re- lated with chronic inflammation not only in adults[17-21] but also in children.[22] WBCC is a marker of chronic inflammation[24] and is known to correlate with the amount of body fat in adults.[25] To our knowledge, this study is the first one that has revealed the association between childhood obesity and increased WBCC. This finding confirms the relation of chronic inflammation with childhood obesity.[22] Childhood obesity may be C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPed  R. Baba et al. / Open Journal of Pediatrics 1 (2011) 4-8 7 more dangerous than adult obesity, as the patients with childhood obesity have longer history of having chronic inflammation than adulthood obesity patients, which can cause early development of cardiovascular diseases. The present study is also the first one that has shown the relation of childhood obesity with increased platelet counts, a well-known risk factor for fatal coronary heart disease in adult population.[26] Taniguchi et al. showed a relationship between platelet count and insulin resis- tance in non-obese adult Japanese type 2 diabetic pa- tients.[27] Thus, increased platelet count may be related with impaired insulin sensitivity in obese children. The mechanisms for the increase in platelet counts are un- known. But, it seems interesting that insulin is thought to reduce platelet sensitivity to aggregating agents such as adenosine diphosphate.[28] The present study shows that body composition is closely related with systolic blood pressure and that obese boys and girls have high risks of having abnor- mally high systolic blood pressure. These findings con- firm the findings of previous studies that childhood and adolescent obesity is related with hyperkinetic circula- tion.[7,29] The close and early association of systolic hypertension with adiposity suggests the role of im- paired autonomic function in the pathogenesis of adipos- ity-associated hypertension. The present study has some limitations. We did not measure blood glucose or insulin activity. Also, the data of waist circumference is lacking. These measurements are essential for the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome. Therefore, addition of these data may provide us further knowledge as to the understanding of childhood obesity or metabolic syndrome and their associations with hae- matological, hepatic and circulatory disorders, which awaits further investigations. REFERENCES [1] Hayman LL, Meininger JC, Daniels SR, McCrindle BW, Helden L, Ross J, et al. Primary prevention of cardio- vascular disease in nursing practice: Focus on children and youth: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Committee on Atherosclerosis, Hyper- tension, and Obesity in Youth of the Council on Cardio- vascular Disease in the Young, Council on Cardiovascu- lar Nursing, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabo- lism. Circulation 2007; 116: 344-57. [2] Weiss R, Dziura J, Burgert TS. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2362-74. [3] Rocchini AP. Childhood obesity and a diabetes epidemic. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 854-5. [4] Strauss RS, Pollack HA. Epidemic increase in childhood overweight. 1986–1998. JAMA 2001; 286: 2845-48. [5] Reilly JJ, Dorosty AR. Epidemic of obesity in UK chil- dren. Lancet 1999; 354: 1874-5. [6] Baba R, Nagashima M, Asai T, Kato Y. Effect of physical activity and readiness for exercise on the development of obesity in adolescents (in Japanese). Jpn J Clin Sports Med 2004; 12: 346-51. [7] Baba R, Koketsu M, Nagashima M, Inasaka H, Yoshi- naga M, Yokota M. Adolescent obesity adversely affects blood pressure and resting heart rate. Circ J 2007; 71: 722-6. [8] Baba R, Iwao N, Iwao S, Koketsu M, Nagashima M, Inasaka H. Risk of obesity enhanced by poor physical ac- tivity in high school students. Pediatr Int 2006; 48: 268-73. [9] DeFronzo RA, Ferrannini E. Insulin resistance. A multi- faceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hy- pertension, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerotic cardiovas- cular disease. Diabetes Care 1991; 14: 173-94. [10] Nguyen NT, Magno CP, Lane KT, Hinojosa MW, Lane JS. Association of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome with obesity: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 to 2004. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87: 3023-8. [11] Rahmouni K, Correia MLG, Haynes WG, Mark AL. Obe- sity-associated hypertension: new insights into mecha- nisms. Hypertension 2005; 45: 9-14. [12] Hall JE, Hildebrandta DA, Kuo J. Obesity hypertension: role of leptin and sympathetic nervous system. Am J Hy- pertens 2001; 14 (suppl 1): S103-15. [13] Wanless IR, Lentz JS. Fatty liver hepatitis (steatohepati- tis) and obesity: An autopsy study with analysis of risk factors. Hepatology 2005; 12: 1106-10. [14] Marceau P, Biron S, Hould FS, Marceau S, Simard S, Thung SN, et al. Liver pathology and the metabolic syn- drome X in severe obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999; 84:1513-7. [15] Marchesini G, Brizi M, Bianchi G, Tomassetti S, Bugianesi E, Lenzi M, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver dis- ease: a feature of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes 2001; 50: 1844-50. [16] Pagano G, Pacini G, Musso G, Gambino R, Mecca F, Depetris N, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome: further evidence for an etiologic association. Hepatology 2002; 35: 367-72. [17] Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS.Obesity-induced inflamma- tory changes in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 2003; 112: 1785-8. [18] Lee YH, Pratley RE, The evolving role of inflammation in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Curr Diab Rep 2005; 5: 70-5. [19] Falcon C, Pfliegler G, Deckmyn H, Vermylen J. The platelet insulin receptor: Detection, partial characteriza- tion, and search for a function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1988; 157: 1190-6. [20] Trovati M, Anfossi G, Cavalot F, Massucco P, Mularoni E, Emanuelli G. Insulin directly reduces platelet sensitivity to aggregating agents: Studies in vitro and in vivo. Dia- betes 1988; 37: 780-6. [21] Westerbacka J, Yki-Järvinen H, Turpeinen A, Rissanen A, Vehkavaara S, Syrjälä M, et al. Inhibition of plate- let-collagen interaction: An in vivo action of insulin abol- ished by insulin resistance in obesity. Arterioscler Thr omb Vasc Biol 2002; 22: 167-72. C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPed  8 R. Baba et al. / Open Journal of Pediatrics 1 (2011) 4-8 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPed [22] Herder C, Schneitler S, Rathmann W, Haastert B, Schneitler H, Winkler H, et al. Low-grade inflammation, obesity, and insulin resistance in adolescents. Clin Endo- crinol Metab 2007; 92: 4569-74. [23] Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establish- ing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000; 320:1240-3. [24] Festa A, D'Agostino R Jr, Howard G, Mykkänen L, Tracy RP, Haffner SM. Chronic subclinical inflammation as part of the insulin resistance syndrome: the Insulin Re- sistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS). Circulation 2000; 102: 42-7. [25] Wilson CA, Bekele G, Nicolson M, Ravussin E, Prat- leyRE. Relationship of the white blood cell count to body fat: role of leptin. Br J Haematol 2003; 99: 447-51. [26] Thaulow E, Erikssen J, Sandvik L, Stormorken H, Cohn PF. Blood platelet count and function are related to total and cardiovascular death in apparently healthy men. Cir- culation 1991; 84: 613-7. [27] Taniguchi A, Fukushima M, Seino Y, Sakai M, Yoshii S, Nagasaka S, et al. Platelet count is independently associ- ated with insulin resistance in non-obese Japanese type 2 diabetic patients. Metabolism 2003; 52: 1246-9. [28] Falcon CR, Cattaneo M, Ghidoni A, Mannucci PM. The in vitro production of thromboxane B2 by platelets of diabetic patients is normal at physiological concentra- tions of ionized calcium. Thromb Haemost 1993; 70: 389-92. [29] Sorof JM, Poffenbarger T, Franco K, Bernard L, Portman RJ. Isolated systolic hypertension, obesity, and hyperkinetic hemodynamic states in children. J Pediatr 2002; 140: 660-6. |