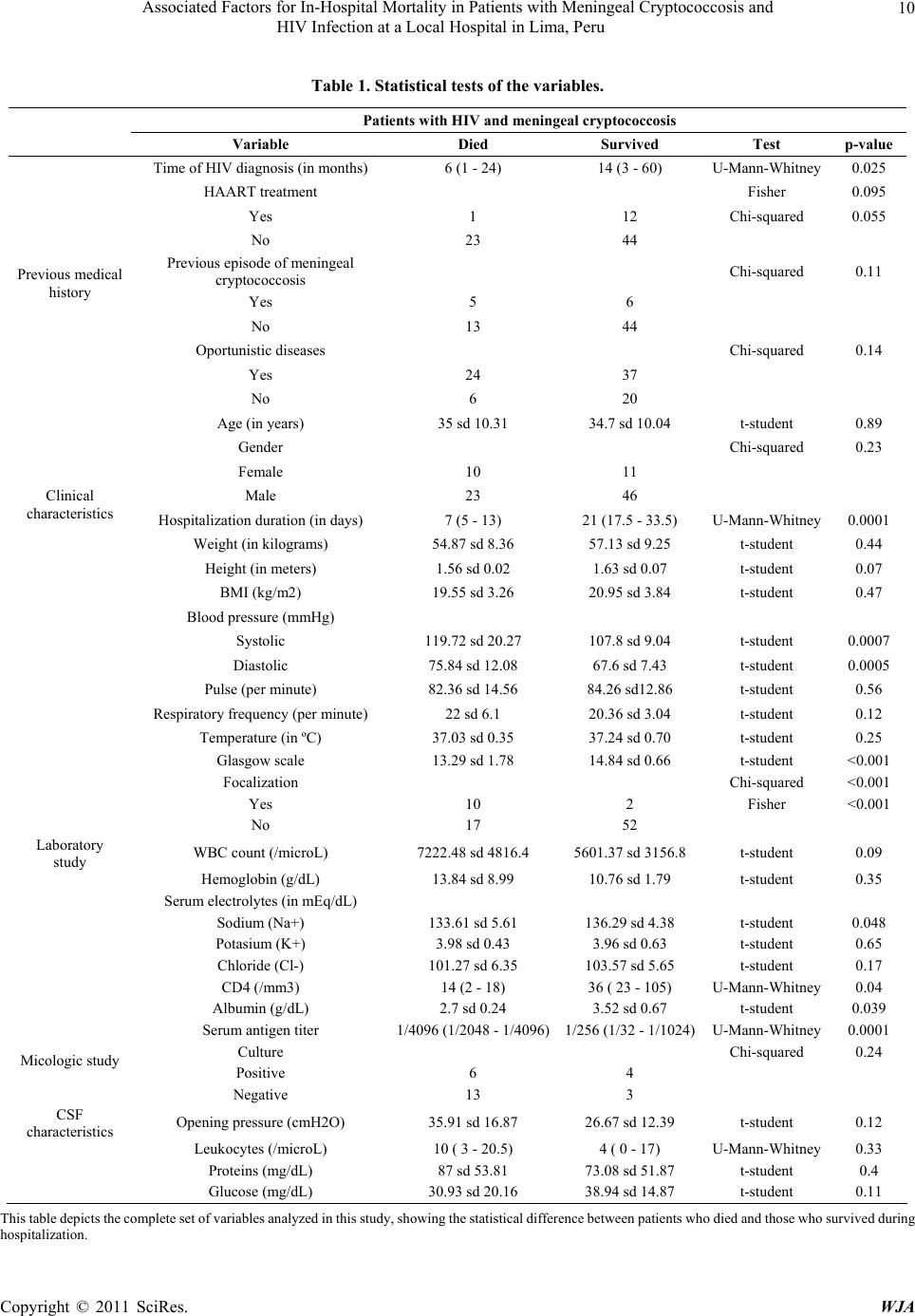

World Journal of AIDS, 2011, 1, 8-14 doi: 10.4236/wja.2011.11002 Published Online March 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/wja) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA 1 Associated Factors for In-Hospital Mortality in Patients with Meningeal Cryptococcosis and HIV Infection at a Local Hospital in Lima, Peru Canessa J.C.1, Cabrera D.1, Eskenazi J.1, Samalvides F1 1Cayetano He re dia University, Lima, Peru. Email: juan.canessa@upch.pe Received March 8th, 2011; revised March 17th, 2011; accepted March 18th, 2011. ABSTRACT Objective: To determine the associated factors for in-hospital mortality in patients with meningeal cryptococcosis and HIV infection at a local hospital in Lima, Peru Materials and me thods: We carried out a case-control study by reviewing the medical histories available at a local hospital in Lima, Peru. We determined the factors associated with mortality using a logistic regression model. Results: The information of 90 patients was analyzed, 37 dead and 53 alive. In the multivariate analysis we found two variables associated with mortality: Glasgow at a dmission (OR = 4. 55 (1.61 – 12.20), p = 0.01) and serum antigen titer greater than 1024 (OR = 20.48 (1.6 – 261.04, p = 0.02). The protective factor found was a longer hospita lization sta y (OR = 0.80 (0.69 – 0.93, p = 0.005).Conclusions: A low Glasgow sco r e and serum antig en titer greater than 1024 are associated factors with mortality, whereas hospitalization length is a protective factor. Keywords: Meningeal Cryptococcosis, Cryptococcus, HIV, Mortality, Death, Cryptococcal Meningitis 1. Introduction Cryptococcosis is an opportunistic disease [1] which is potentially mortal [2,3], caused by the encapsulated cos- mopolitan fungus Cryptococcus neoformans [4,5], of which three variants exist: neoformans, grubii (most prevalent worldwide) [4,6,7] and gatti [8,9]. Its pato- genicity is related to patients with altered T-cell immunity [8,10], particularly those affected with the Human Im- munodeficiency Virus (HIV) and with CD4 blood counts below 100/m m3 [5,8]. Cryptococcosis defines AIDS in up to 25% of cases [11,12]. This patho gen is foun d in pigeon droppings [4,5] and i n the heartwood of eucalyptus trees in tropical and sub- tropical areas[5,7,13]. It most often enters the host through inhalation [7,8], forming a primary infection in immunocompetent patients [8]. In those immunocom- promised, it travels hematogenously with a predilection for the central nervous system [8], causing an acute or subacute meningoencephalitis [14]. The probability of acquiring cryptococc osis in HIV-infected patients wh o are not under HAART (Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Ther- apy) is around 10-30 % [12,15], with an annual incid ence in Latin- American series of 1.1-3.7 per m illion inha bitants per year [12]. The most common signs and symptoms are: headache, fever [7,10,16], vomiting [15,16], cranial nerve palsy [7,8], altered consciousness [10], convulsions [8], visual alterations [7,15,17], dermatological lesions [10], but only one third of patients will present classic meningeal signs [16]. The natural history of the di sease shows a 3 5% survival at day 14 and 0% survival at day 42 [3] . Factors that have been associated to mortality at ad- mission are: cryptococcemia [1,18], absence of treatment with HAART [19], abnormal mental status [8,11,19], CD4 values below 5 0/mm3 [20], intrac ranial hype rtension [10,11], malnutrition [19], hyponatremia [21], lumbar puncture’s opening pressure greater than 25cmH2O [7,22,23], high antigen titer [7,10,23], low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) inflammatory response [7,21,23], and an abnormal cerebral image (magnetic resonance or com- puted tomography) [10]. Mortality since the extended use of HAART has de- creased [25-29], although the mortality in the acute phase is still around 10-20% [30,31]. In countries in South America, Africa and Asia, the use of HAART is still low [12,25,32,33]. On the other hand, prognosis is still poor in patients receiving antifungal m onotherapy, with a 60-65%  Associated Factors for In-Hospital Mortality in Patients with Meningeal Cryptococcosis and 9HIV Infection at a Local Hospital in Lima, Peru failure at week ten [10,34]. Besides, because of its high toxicity the treatment itself has been related to death, especially in the absence of an adequate c oncom itant flui d therapy [19]. It is important to mention that in some Af- rican countries , meningeal cryptococcosis mortality is even higher than that caused by tuberculosis [28]. The aim of this study is to determine the associated factors for in-hospital mortality in patients with meningeal cryptococcosis and HIV-infection at a hospital in Li- ma-Peru because of the nonexistence of previous studies of this sort in our country. 2. Materials and Methods 2.1. Study Design We carried out an observational, longitudinal case-control study, in patients with meningeal cryptococcosis and HIV-infection treated at a local hospital in Lima, Peru between January 1st 2000 and December 31st 2009. We included as cases, patients who died during hospitaliza- tion, with a confirmed diagnosis of HIV-infection [8,26], and of meningeal cryptococcosis by either CSF cultures, positive serum an tigen titers or a positive CSF In dian Ink, and symptoms compatible with meningoencephalitis [8,13]. In the controls, we included patients who survived the hospitalization, and who had an equally confirmed diagnosis of both HIV-infection and meningeal crypto- coccosis. We excluded from both branches of the study patients without a confirmed diagnosis of meningeal cryptococcosis, those immunocompromised by others causes rather than HIV, those who received antifungal treatment within one week previous to admission, or those with contraindications to a lumbar puncture. In recurrent patients, only the first hospitalizatio n was taken into account. 2.2. Gathering of Information We revised both medical records and epicrisis, to obtain the following information: past medical history [24,35], clinical, laboratory and mycological findings [26] and CSF characteristics (initial opening pressure, cellularity, cytochemical analysis, Indian Ink and fungal culture [2,26]. Finally, we registered total hospitalization dura- tion and the outcome. 2.3. Statistical Analysis Sample size was calculated using EpiInfo v6.1, with a 1:2 ratio (cases:controls), a statistic significance of 95% and a statistical power of 80% [18]. Considering expo- sure percentages among an opening pressure greater than 25cmH2O, we obtained a required sample size of 10:20 (OR = 20.4) [23], while in the case of serum antigen titer greater than 1/1024, we obtained a sample size of 27:54 (OR = 3.17) [36]. Qualitative variables were analyzed using chi-squared and Fisher, while quantitative variables used t-student distribution and U-Mann-Whitney, all of them with a significance level of 0.05. Afterwards, we carried out a multiple logistic regression. We obtained the consent of the ethical department of both Cayetano Heredia University and Cayetano Heredia Hospital. 3. Results A total of 90 patients were included i n t he study (3 3 ca ses and 57 controls). The range of age varied between 20 and 74 years, with a m ean value of 35 (sd 10.31) years in those who died and 34.7 (sd 10.04) in those who survived. 76.67% of patients were male. As past medical history, 16.25% received HAART before admission (12 of which survived, while only 1 who died). We found a mean time between HIV diagnosis and hospital admission of 6 months in the cases versus 14 months in the controls (p = 0.025). Hospitalization stay was of 7 days on average in pa- tients wh o die d, com pared to 21 days i n thos e who di d not die (p = 0.0001). Mean arterial pressure was of 111.77/70.34 mmHg, with differences between cases and controls of 119.72/75.84 and 107.8/67.6 respectively (p = 0.0007 in the systolic and p = 0.0005 in the diastolic). Furthermore, the body mass index (BMI) was on average 20.62 kg/m2. In the neurological examination, the mean Glasgow score was 14.4, with values of 13.29 in those who died, contrasted with 14.84 in t hose who did not (p < 0.001). The presence of focalization in the cases was 37% (n = 10) while in the controls it was 3.7% (n = 2). In laboratory studies, we observe that the mean value for CD4 in patients who died was 14/mm3, compared to a value of 36/mm3 in those who survived (p = 0.04), while in the case of albumin, the mean in this study was of 3.14 g/dL (2.7 g/dL in the former group and 3.52 g/dL in the latter, p = 0.039). Finally, median serum antigen titer was 1/4096 in the cases, while in the controls it was 1/256 (p = 0.0001). Referring to CSF characteristics, we found a mean ini- tial opening pressure of 30.94 cmH2O (35.91 in the dead versus 26. 67 in those who s urvived, p = 0.1 2), white blood cell count was on average 38.62, while glucose and pro- teins scored 36.63 and 76.9 mg/dL, respectively. The remaining results can be consulted in Table 1. In the logistic regression, the protective factor was hospitalization duration, with an odds ratio of 0.80 (p = 0.005) in the multiv ariate an alysis. On the other h and, th e associated factors to in-hospital mortality in the univariate analysis were: blood pressure (OR = 1.07, p = 0.004 and OR = 1.10, p = 0.003) in the case of systo lic and diasto lic Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA  Associated Factors for In-Hospital Mortality in Patients with Meningeal Cryptococcosis and HIV Infection at a Local Hospital in Lima, Peru Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA 10 Table 1. Statistical tests of the variables. Patients with HIV and meningeal cryptococcosis Variable Died Survived Test p-value Time of HIV di agnosis (in months) 6 (1 - 24) 14 (3 - 60) U-Mann-Whitney 0.025 HAART treatment Fisher 0.095 Yes 1 12 Chi-squared 0.055 No 23 44 Previous episode of meningeal cryptococcosis Chi-squared 0.11 Yes 5 6 No 13 44 Oportunistic diseases Chi-squared 0.14 Yes 24 37 Previous medical history No 6 20 Age (in years) 35 sd 10.31 34.7 sd 10.04 t-student 0.89 Gender Chi-squared 0.23 Female 10 11 Male 23 46 Hospitalization duration (in days) 7 (5 - 13) 21 (17.5 - 33.5) U-Mann-Whitney 0.0001 Weight (in kilograms) 54.87 sd 8.36 57.13 sd 9.25 t-student 0.44 Clinical characteristics Height (in meters) 1.56 sd 0.02 1.63 sd 0.07 t-student 0.07 BMI (kg/m2) 19.55 sd 3.26 20.95 sd 3.84 t-student 0.47 Blood pressure (mmHg) Systolic 119.72 sd 20.27 107.8 sd 9.04 t-student 0.0007 Diastolic 75.84 sd 12.08 67.6 sd 7.43 t-student 0.0005 Pulse (per minute) 82.36 sd 14.56 84.26 sd12.86 t-student 0.56 Respiratory frequency (per minute) 22 sd 6.1 20.36 sd 3.04 t-student 0.12 Temperature (in ºC) 37.03 sd 0.35 37.24 sd 0.70 t-student 0.25 Glasgow scale 13.29 sd 1.78 14.84 sd 0.66 t-student <0.001 Focalization Chi-squared <0.001 Yes 10 2 Fisher <0.001 No 17 52 Laboratory stud WBC count (/microL) 7222.48 sd 4816.4 5601.37 sd 3156.8 t-student 0.09 Hemoglobin (g/dL) 13.84 sd 8.99 10.76 sd 1.79 t-student 0.35 Serum electrolytes (in mEq/dL) Sodium (Na+) 133.61 sd 5.61 136.29 sd 4.38 t-student 0.048 Potasium (K+) 3.98 sd 0.43 3.96 sd 0.63 t-student 0.65 Chloride (Cl-) 101.27 sd 6.35 103.57 sd 5.65 t-student 0.17 CD4 (/mm3) 14 (2 - 18) 36 ( 23 - 105) U-Mann-Whitney 0.04 Albumin (g/dL) 2.7 sd 0.24 3.52 sd 0.67 t-student 0.039 Serum antigen titer 1/4096 (1/2048 - 1/4096)1/256 (1/32 - 1/1024) U-Mann-Whitney 0.0001 Culture Chi-squared 0.24 Micologic study Positive 6 4 Negative 13 3 CSF characteristics Opening pressure (cmH2O) 35.91 sd 16.87 26.67 sd 12.39 t-student 0.12 Leukocytes (/microL) 10 ( 3 - 20.5) 4 ( 0 - 17) U-Mann-Whitney 0.33 Proteins (mg/ d L ) 87 sd 53.81 73.08 sd 51.87 t-student 0.4 Glucose (mg/dL) 30.93 sd 20.16 38.94 sd 14.87 t-student 0.11 This table de picts t he c omplet e set of variable s ana lyze d in this s tudy, showing t he sta tistica l diffe rence betwee n patie nts who died a nd thos e who sur vived du ring ospitalization. h  Associated Factors for In-Hospital Mortality in Patients with Meningeal Cryptococcosis and 11 HIV Infection at a Local Hospital in Lima, Peru respectively, Glasgow score (OR = 3.13, p < 0.001), se- rum antigen titer (OR = 23.13, p = 0.003) and focalization (OR = 15.29, p = 0.001). In the multivariate analysis, the factors that remained associated to a negative outcome were serum antigen titers (OR = 4.55, p = 0.01) and Glas- gow score (OR = 20.48, p = 0.02). The complete da ta for the logistic regression model can be reviewed in Table 2. 4. Discussion This is the first investigation carried out in Peru aiming to find the mortality-associated factors in patients with meningeal cryptococcosis and HIV infection, despite the high mortality among them. The significant clinical pat- terns were: blood pressure, serum albumin level and de- prived mental status. Blood pressure was higher in those patients who died, probably reflecting intracranial hy- pertension [29], concurring with previous studies in New Guinea [36] and Thailand [37]. Similarly, it was found that patients presented with lower serum albumin levels in the case group, as an indirect indication of malnutrition and impl ying that these patient s had a worse previous state at admission. Referring to the neurological findings, the scores in the Glasgow scale were lower in t hose who died, and that same patients group had focalization more often, matching the findings of other studies [8,11,19,22] and possibly si gnaling that t hese patient s at a dmission were i n a poorer mental state, either because of a longer disease evolution or because of factors inherent to the subject. In the laboratory study, patients who died presented hy- ponatremia more often, exhibiting an internal imbalance and a greater systemic compromise. Subramian et al. in 2005 reported similar findings [21 ], but it is still not po s- sible to propose a cut point below which it can be con- sidered hazardous. In what concerns CD4 levels, those in the cases were substantially lower than those in the con- trols. In other studies it has been reported a global mean CD4 value of 45/mm3 in meningeal cryptococcosis pa- tients [12,15,24], without differentiating between those Table 2. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression. Category Variable OR 95% (IC) a p-value OR 95% (IC) b p-value Time of HIV di agnosis (in months) 0.98 (0.95 - 1.004) 0.11 HAART treatment 0.087 Yes 0.15 (0.019 -1.3) Previous medical history No 1 Oportunistic diseases 0.14 Yes 2.16 (0.75 - 6.16) No 1 Hospitalization duration (in days) 0.87 (0.81 - 0.93) >0.001 0.80 (0.69 - 0.93) 0.005 Blood pressure ( in mmHg) Systolic 1.07 (1.02 - 1.12) 0.004 Diastolic 1.10 (1.03 - 1.17) 0.003 Glasgow scale 3.13 (1.67 - 5.88) >0.001 4.55 (1.61 - 12.20) 0.01 Focalization 0.001 Yes 15.29 (3.04 - 76.81) Clinical characteristics No 1 WBC count (/microL) 1.00 (0.99 - 1.00) 0.09 Serum sodium (mEq/dL) 1.14 (1.00 - 1.30) 0.055 CD4 count 1.12 (0.97 - 1.32) 0.14 Laboratory study Serum albumin 125 (0.37 - 10000) 0.1 Micologic study Serum antigen titer 23.13 (2.87-186.1) 0.003 20.48 (1.6 - 261.04) 0.02 This table presents the univariate (ICa) and multivariate (ICb) analysis for those variables that resulted significant in the statistical test shown in table 1. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA  Associated Factors for In-Hospital Mortality in Patients with Meningeal Cryptococcosis and 12 HIV Infection at a Local Hospital in Lima, Peru who die and those who survive. In this study, we obtained a much lower mean in patients who died. Some publications state that up to 60% of patients with meningeal cryptococcosis present with a serum antigen titer of 1/1024 [35 ] or 1/2048 (CSF) [6,19,23], with a 90% sensibility [8,20,38]. In our study, the cut point in the case of the initial serum antigen was also located at 1/1024, because above that dilution the proportion of deaths in- creased importantly. However, the follow-up dilutions of antigen titer do not predict th e final outcome [39,40]. In what concerns the CSF, a previous study in our country showed that 57.9% of the initial opening pres- sures in the lumbar puncture were abnormally high [15]. In our c ase, the m ean opening pre ssure was hi gher in th ose who died, but without finding significant differences between bot h groups. Opening pressures a bove 25 cmH2O have been associated to higher short-term mortality [7,23,35] and with a requirement for daily decompression [19,29,41]. The fact that we did not find this associati on is probably due to the fact that some of the records did not contain data for this specific variable, even though the procedure was executed. Having said that, it is described that as many as 25% of patients with cryptococcosis can have a normal CSF study [16,24]. In the multivariate analysis, we found as a protective factor the duration of hospitalization, resulting that each additional day reduced in 29% the probability of dying. In studies in other countries, it has been reported that the mean time of death is around 10 to 14 days [7,11,19], while in our case it was much shorter (7 days) [23]. This could be explained because patients in our country take longer to seek for professional help, presenting at the emergency department in a more debilitated neurologic and systemic state, and dying sooner because of compli- cations such as intracranial hypertension. Mortality-associated factors included a low score in the Glasgow scale and elevated serum antigen titers. In the former, it was found that the decrease in one point in the scale meant 4.55 times more probability of dying. In the case of the serum antigen titers, the variable was di- chotomized with a cut point at 1/1024. This concurs to Dromer et al. prospective study where a 1/512 cut point was proposed as a predictor of therapeutic failure at day 14 [10]. On another level, neurologic focalization is as- sociated to death in the univariate regression model, but was diluted in the multivariate study, proba bly because of a lack of power of the study. This contrasts to publications by Cachay et al. who were able to link focalization with complications including death [22]. REFERENCES [1] S. Jean, C. Fang and W. Shau, et al, “Cryptococcaemia: clinical features and prognostic factors,” Q J Med, Vol. 95, No. 8, 2002; pp. 511- 518. [2] V. Lakshmi, T. Sudha and V. Teja, et al, “Prevalence of central nervous system cryptococcosis in human immudeficiency virus reactive hospitalized patients,” Indian Journal of Medical Science, Vol. 25, No. 2, 2007; pp. 146-149. [3] P. Mwaba, J. Mwansa and C. Chintu, et al, “Clinical presentation, natural history, and cumulative death rates of 230 adults with primary cryptococcal meningitis in Zambian AIDS patients treated under local conditions,” Postgraduate Medical Journal, Vol. 77, No. 941, 2001; pp. 769-773. doi:10.1136/pmj.77.914.769 [4] B. Bustamante and D. Swinne, “Aislamiento de Cryptococcus neoformans variedad gattii en dos pacientes peruanos,” Revista Iberoamericana de Micologia, Vol. 15, 1998, pp. 22-24. [5] C. Klock, M. Cerski and L. Goldani, “Histopathological aspects of neurocryptococcosis in HIV-infected patients: autopsy reports of 45 patients,” International Journal of Surgical Pathology, Vol. 17, No. 6, 2009; pp. 444-448. [6] C. Charlier, F. Dromer and C. Lévêque, et al, “Cryptococcal neuroradiological lesions correlate with severity during cryptococcal meningoencephalities in HIV-positive patients in the HAART era,” PLoS Med, Vol. 3, No. 4, 2008; pp. 1-7. [7] J. Jarvis and T. Harrison, “HIV-associated cryptococcal me- ningitis,” AIDS, Vol. 21, No. 16, 2007; pp. 2119-2129. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282a4a64d [8] D. Cangelosi, L. De Carolis and L. Trombetta, et al, “Cr ipt oco cosis mení ngea asociada al SIDA. Aná lisis de los pacientes varones HIV(+) con criptococosis meníngea internados en la Sala 11 del Hospital Francisco J Muñiz,” Revista de la Asociación Médica Argentina, Vol. 120, No. 3, 2007; pp. 25-30. [9] T. Moreira, M. Ferreira and R. Marques Ribas, et al, “Criptococose: estudio clínico-e pidemiológico, laboratorial e das variedades do fungo em 96 pacientes,” Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical, Vol. 39, No. 3, 2006, pp. 255-258. doi:10.1590/S0037-86822006000300005 [10] F. Dromer, S. Mathoulin-Pélissier and O. Launay, et al, “Determinants of disease presentation and outcome during cryptococcosis: the crypto A/D study,” PLoS Med, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2007; pp. 0297-0308. [11] A. Brouwer, A. Rajanuwong and C. Wirongrong, et al, “Combination antifungal therapies for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: a randomised trial,” Lancet, Vol. 363, No.5, 2004, pp. 1764-1767. [12] J. Lizarazo, M. Linares and C. de Bedout, et al, “Estudio clínico y epidemiológico de la criptococosis en Colombia: resultados de nueve años de la encuesta nacional,” Biomédica, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2007; pp. 94-109. [13] A. Chakrabarti, “Epidemiology of central nervous system mycoses,” Neurology India, Vol. 55, No. 3, 2007, pp. 191-197.doi:10.4103/0028-3886.35679 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA  Associated Factors for In-Hospital Mortality in Patients with Meningeal Cryptococcosis and 13 HIV Infection at a Local Hospital in Lima, Peru [14] L. Trombetta, G. Poustis and A. Bocassi, et al, “Líquido cefalorraquídeo en pacientes con criptococosis asociada al SIDA,” Acta Bioquímica Clínica Latinoamericana, Vol. 42, No. 1, 2008; pp. 61-64. [15] R. Andrade, “Características epidemiológico-clínicas de un grupo de pacientes con SIDA y meningoencefalitis criptococócica en el HNCH,” Tesis para optar por el grado de Médico Cirujano, UPCH: Lima - Perú,2001. [16] H. Manji and R. Miller, “The neurology of HIV infection,” Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, Vol. 75, Suppl. 1, 2004; pp. i29-i35. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.034348 [17] R. Thakur, S. Sarma and S. Kushwaha, “Prevalence of HIV- associated cryptococcal meningitis and utility of microbiological determinants for its diagnosis in a tertiary care center,” Indian Journal of Pathology and Microbiology, Vol. 51, No. 2, 2008; pp. 212-214. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.41689 [18] A. Comarú, C. Bittencourt and F. de Mattos, et al, “Cryptococcemia. An analysis of 28 cases with emphasis on the clinical outcome and its etiologic agent,” Revista Iberoamericana de Micologia, Vol. 21, 2004, pp. 143-146. [19] A. Kambugu, D. Meya and J. Rhein, et al, “Outcomes of Crypto- coccal Meningitis in Uganda before and after the availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2008; Vol. 46, No. 6, pp. 1694-1701. [20] B. Ojikutu, H. Zheng and R. Walensky, et al, “Predictors of mortality in patients initiating antiretroviral therapy in Durban, South Africa,” South African Medical Journal, Vol. 98, No. 3, 2008, pp. 204-208. [21] S. Subramanian and D. Mathai, “Clinical manifestations and management of cryptococcal infection,” Postgraduate Medical Journal, Vol. 51, Suppl. 1, 2005; pp. S21-S26. [22] E. Cachay, J. Caperna and A. Sitapati, et al, “Utility of clinical assessment, imaging, and cryptococcal antigen titer to predict AIDS-related complicated forms of cryptococcal meningitis,” AIDS Research and Therapy, Vol. 7, No. 29, 2010; pp. 1-6. [23] J. Graybill, J. Sobel, M. Saag, et al, “Diagnosis and management of increased intracranial pressure in patients with AIDS and cryptococcal meningitis,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 30, No. 1, 2000; pp. 47-54. doi:10.1086/313603 [24] C. Darras-Joly, S. Chevret, M. Wolff, et al, “Cryptococcus neoformans infection in France: epidemiologic features of and early prognostic parameters for 76 patients who were infected with Human Immunodeficiency Viru s,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 23, No. 8, 1996; pp. 369-376. doi:10.1093/clinids/23.2.369 [25] S. Antinori, A. Ridolfo, M. Fasan, et al, “AIDS-associated cryptococcosis: a comparison of epidemiology, clinical features, and outcome in the pre- and post-HAART eras. Experience of a single centre in Italy,” HIV Medicine, Vol. 10, 2009; pp. 6-11. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00645.x [26] S. Chottanapund, P. Singhasivanon and J. Kaewkungwal, et al, “Survival time of HIV-infected patients with cryptococcal meningitis,” Journal of The Medical Association of Thailand, Vol. 90, No. 10, 2007, pp. 2104-2111. [27] T. Lu, H. Chang and L. Chen, et al, “Changes in causes of death and associated conditions among persons with HIV/AIDS after the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy in Taiwan,” Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, Vol. 105, No. 7, 2006; pp. 604-609. doi:10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60158-3 [28] B. Park, K. Wannemuehler and B. Marston, et al, “Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS,” AIDS, Vol. 23, No. 4, 2009; pp. 525-530. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e328322ffac [29] J. Perfect, W. Dismukes and F. Dromer, et al, “Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal di seas e: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 50, No. 1, 2010, pp. 291- 322. [30] O. Lortholary, G. Poizat and V. Zeller, et al, “Long-term outcome of AIDS-associated cryptococcosis in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy,” AIDS, Vol. 20, No. 17, 2006, pp. 2183-2191. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000252060.80704.68 [31] J. Perfect, “Cryptococcus neoformans,” Principles and practice of infectious diseases, Philadelphia, 2005, pp. 2997-3012. [32] R. Sobhani, A. Basavaraj and A. Gupta, et al, “Mortality & clinical characteristics of hospitalized adult patients with HIV in Pune, India,” Indian Journal of Medical Research, Vol.126, No. 8, 2007; pp. 116-121. [33] T. Warkentien and N. Crum-Cianflone, “An update on Cry ptococcus among HIV-infect ed patients,” International Journal of STD & AIDS, Vol. 21, No. 10, 2010, pp. 679-684. doi:10.1258/ijsa.2010.010182 [34] P. Robinson, M. Bauer and M. Leal, et al, “Early mycological treatment failure in AIDS-associated cryptococcal meningitis,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 28, No. 1, 1999, pp. 82-92. doi:10.1086/515074 [35] U. Jongwutiwes, S. Sungkanupar ph and S. Kiertibu ranakal, “Comparison of clinical features and survival between cryptococcosis in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-positive and HIV-negative patients,” Japanese Journal of Infectious Disease, Vol. 61, 2008, pp. 111-115. [36] R. Seaton, S. Naraqi and J. Wembri, et al, “Predictors of outcome in Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii meningitis,” Q J Med, Vol. 89, 1996, pp. 423-428. [37] J. Fan-Harvard, P. Yamaguchi and E. Smith, et al, “Diastolic hypertension in AIDS patients with cryptococcal meningitis,” American Journal of Medicine, Vol. 93, 1992, pp. 347-348. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(92)90245-7 [38] P. Imwidthaya, “N P. Cryptococcosis in AIDS,” Postgraduate Medical Journal, Vol. 76, 2000, pp. 85-88. doi:10.1136/pmj.76.892.85 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA  Associated Factors for In-Hospital Mortality in Patients with Meningeal Cryptococcosis and HIV Infection at a Local Hospital in Lima, Peru Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA 14 [39] W. Powderly, G. Cloud and W. Dismukes, “Measurment of cryptococcal antigen in serum and cerebrospinal fluid: value in the management of AIDS-associated cryptococcal meningitis,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 18, No. 5, 1992, pp. 789-792. [40] A. Spinello, A. Radice and L. Galimberti, “The role of cryptococcal antigen assay in diagnosis and monitoring of cryptococc al menin gitis ,” Journal of Clinical Microbiology, Vol. 43, No. 11, 2005, pp. 5828-5829. [41] P. Pappas, “Managing cryptococcal meningitis is about handling the pressure,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 40, No. 1, 2005, pp. 480-482.

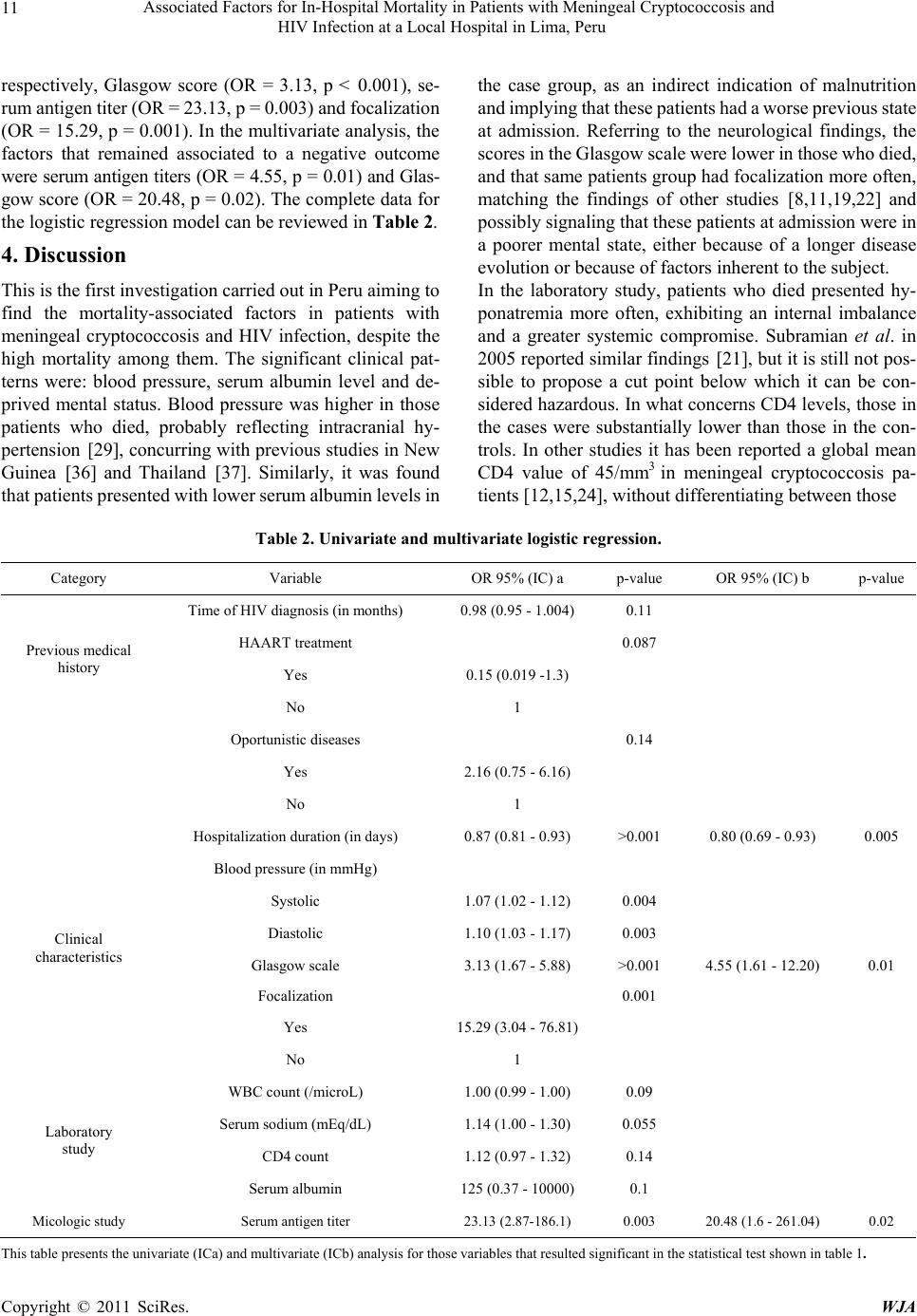

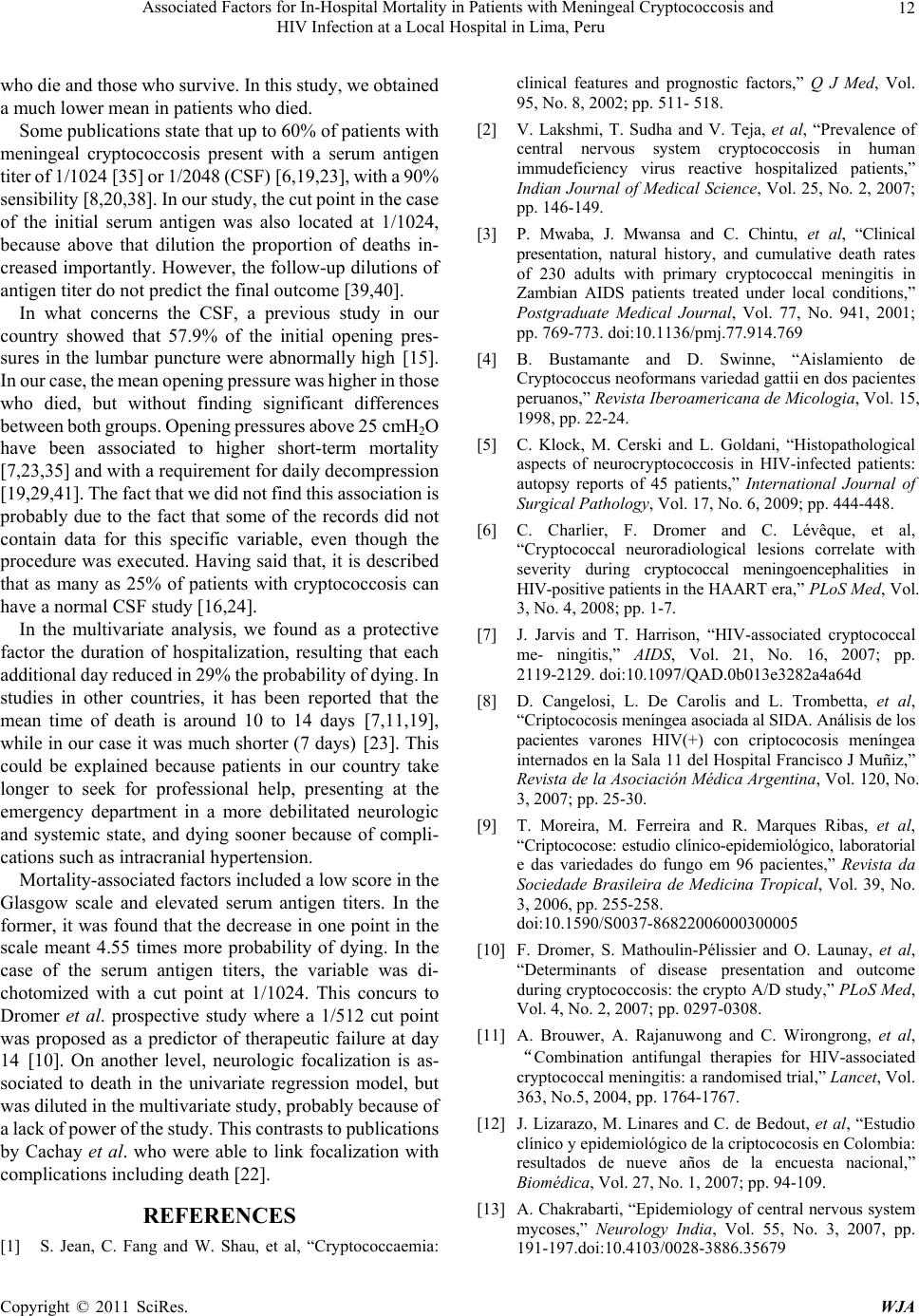

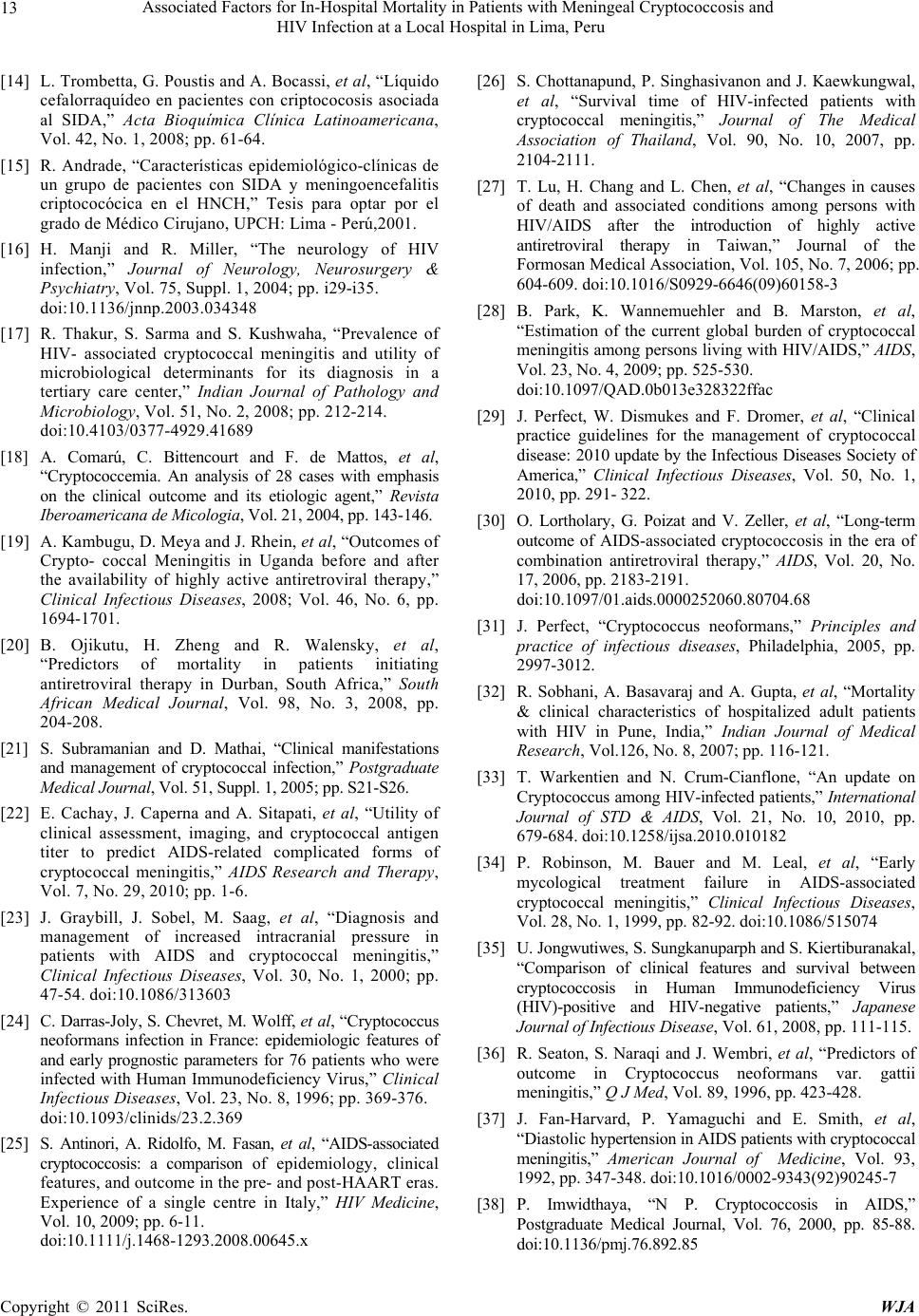

|