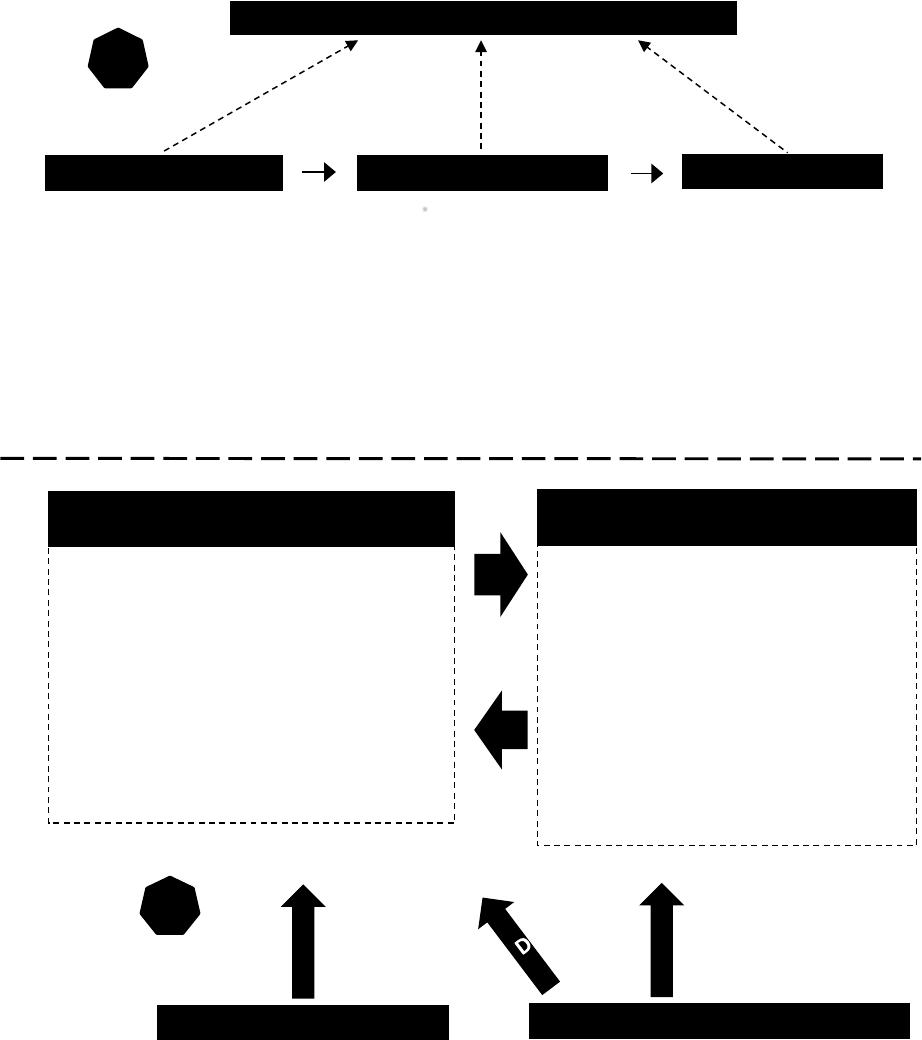

Psychology 2014. Vol.5, No.2, 151-159 Published Online February 2014 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2014.52024 OPEN ACCESS Conceptualization of Hypersexual Disorder with the Behavioral-Cognitive Inhibition Theory Nenad Paunović, Jonas Hallberg Center for Andrology and Sexual Medicine, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden Email: nenad.paunovic@karolinska.se, jonas.hallberg@karolinska.se Received December 20th, 2013; revised January 17th, 2014; accepted February 16th, 2014 Copyright © 2014 Nenad Paunović, Jonas Hallberg. This is an open access article dis tributed un der the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Nenad Paunović, Jonas Hallberg. All Copyright © 2014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. Hypersexual disorder is conceptualized with the behavioral-cognitive inhibition (BCI) theory. The current article focuses on the following aspects: (a) triggers of dysfunctional sexual behaviors and fantasies, (b) dysfunctional beliefs of excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies, (c) negative interpretations of triggers of sexual behaviors and fantasies, (d) excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies as avoidance behaviors, (e) consequences of excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies vs. healthy coping strategies, (f) sexual behav- iors as inhibitors of distressing memories associated with negative beliefs, (g) sexual fantasies and other valued memories as inhibitors of dysfunctional memories associated with negative beliefs, and (h) behav- ioral activation of valued activities as inhibitors of sexual behaviors and distressing memories. Some im- portant issues are discussed. Keywords: Behavioral-Cognitive Inhibition Theory; Hypersexual Disorder; Negative Beli ef s ; Avoidance Behaviors; Inhibition; Valued Memories; Dysfunctional Memories Introduction The aim of this article is to conceptualize hypersexual dis- order, in accordance with the proposed criteria for the DSM-V, with the behavioral-cognitive inhibition theory. An initial at- tempt to such a conceptualization has been made (Paunovic, 2010a). The behavioral-cognitive inhibition theory was first introduced in order to conceptualize posttraumatic stress dis- order (PTSD) and other psychopathology disorders (Paunovic, 2010b). The current conceptualization has been developed by taking into consideration (a) important factors in current con- ceptualizations and treatments of hypersexual-related disorders (Adams & Robinson, 2001; Gilliland, South, Carpenter, & Hardy, 2011; Giugliano, 2006; Hardy, Ruchty, Hull, & Hyde, 2010; Howard, 2007; Kingston & Firestone, 2008; Klontz, Garos, & Klontz, 2005; Putnam, 2000; Robinson, 1999; Same- nov, 2011; Yoder, Virden, & Amin, 2011), and (b) the authors clinical experience with hypersexual disorders in the context of a current research project. The aim of this project is to develop an effective cognitive-behavioral treatment for hypersexual dis- order. The current article focuses on the development of a theoretical model whose aim is to pinpoint proposed maintain- ing factors in hypersexual disorder (see Figure 1). These fac- tors include: (a) Negative beliefs and interpretations of hypersexual beha- viors, fantasies, urges, triggers and consequences; (b) Avoidance and escape functions of sexual behaviors and fantasies; (c) Dysfunctional inhibition of valued memories by negative memories associated with dysfunctional beliefs or by current contingencies, and; (d) Correction of dysfunctional respondent-functional-beliefs memories that maintain dysfunctional sexual behaviors and fan- tasies. Triggers of Excessive Sexual Beha viors, Fantasies and Urges Four different categories of triggers that may set of hyper- sexual behaviors, fantasies and urges. Triggers include sexual and non-sexual related stimuli, and they can be external vs. internal (i.e., env ironm ental vs. cognitions and memory). External Sexual-Related Triggers to Hypersexual Behaviors, Fantasies and Urges External sexual-related stimuli that trigger sexual behaviours, fantasies and/or urges include, but may not be limited to (a) individuals that are perceived in one’s everyday life, (b) be- haviours of others, (c) non-personal stimuli such as pictures (e.g. commercials), magazines or movies of sexually attractive individuals or behaviours. External Non-Sexual-Related Triggers to Hypersexual Behaviors, Fantasies and Urges External non-sexual-related triggers include (a) individuals, situations or events that elicit negative emotions, (b) current distress, stress or crisis, or (c) stimuli that elicit positive emo- tions and sexual feelings or interest.  N. PAUNOVIĆ, J. HALLB ERG OPEN ACCESS Figure 1. Behavioral-cognitive inhib itio n th eo ry for hypersexual disorder: (1) A. Sexual and non-sexual stimuli function as triggers to starting to en g age in excessive sexual behav iors and fantasies; B. Different t ypes of sexual behaviors and fantasies can be utilized as dysf unctional coping strategies; C. Consequences of sexual behaviors and fantasies; and D. Negative or dysfunctional interpretations and beliefs about triggers, sexual beha- viors/fantasies and their consequences; (2) A. Behavior-memory inhibition: excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies may shut-down (i.e., pre- vents new learning) distressing memories associated with negative beliefs (sexual and/or non-sexual) or therapeutically inhibit such memories (i.e., leads to n ew learning); B. Dysfunction al memories associated with negative beliefs may inhibit v alued and meaningful memories; C. Va- lued and meaningful memories may therapeutically inhibit distressing memories associated with negative beliefs; D. Current valued activities and functional coping may inhibit distressing memories associated with negative beliefs, and E. Reinforce plus expand valued memories. Negative emotions, that constitute emotional responses to current environmental stimuli, such as loneliness, boredom, sadness, anxiety or anger, can start to function as triggers to excessive sexual activities. Sex with others (e.g., infidelity) Pleasurable sexual emotions-positively reinforcing activity-dysfunctional or negative beliefs Negatively reinforcing sexual behaviors (e,g, cybersex) Sexual arousal-negative reinforcement-dysfunctional or negative beliefs Negative sexual and personal experiences with partner Distressing emotional responses-positively punishing experiences-negative beliefs of self/partner Negative event (e.g., trauma, abandonment, social, loss) Negative distressing emotions-e.g. negative re inforcement-negative beliefs of self and others Relationship and sexual experiences with partner Pleasurable emotions-positively reinforcing activities- positive beliefs of self/partner Valued relationships Valued positive emotions-positively reinforcing activities-positively valued people and relationships Other valued life areas (job, sexual, achievements, activities) Valued positive emotions-positively reinforcing activities-meaningful beliefs of life area, self, others Current meaningful sexual fantasies Pleasurable sexual emotions-positively reinforcing sexual activity-positive personal meaning MEMORY-MEMORY INHIBITION A BEHAVIOR- MEMORY INHIBITION Current excessive sexual behaviors 2 B C E Current valued activities and functional coping BEHAVIORS Sexual-related stimuli •Attractive persons or other sexual stimuli •Distressing reminders of painful sexual experiences •Reminders of positive sexual experiences •Sexual interest, desire, urges Non-sexual-related stimuli •Negative and distressing emotions •Memories of negative events and beliefs •Stressful/distressing stimuli and emotions •Mast urbat ion •Pornography •Adult consenting sex •Cybersex •Telephone Sex •Strip Clubs Topography •Frequency, intensity, duration D. Currentnegative or dysfunctional beliefs and interpretations BELIEFS •Negative reinforcement •Negative consequences in valued life areas (relationships, job, monetary etc.) •Shut-down or retrieval prevention of negative emotions, beliefs, memori es •Sexual positive reinforcement •Sexual satiation •De-inhibition of valued emotions, beliefs, memories (functional) •Inhibition of negative emotions, beliefs, memories (functional) 1 A. Sexual behavior triggersB. Sexual behaviors/fantasiesC. Consequences Distressing/dysfunctional memories (respondent- funct iona l-beliefs memory elements) Valued memories (responde nt -func t ional - beliefs memory elements) N. PAUNOVIĆ, J. HALLB ERG OPEN ACCESS Sexual-Related Memories as Triggers to Hypersexual Behaviors, Fantasies and Urges Memories of negative sexual experiences may function as triggers to start engaging in current sexual behaviours and fan- tasies. Negative sexual experiences may include sexual assault or other types of negative sexual experiences. Negative sexual experiences, distressing emotional and physiological responses, and negative meanings and behaviours become encoded (per- ceived) and stored in memory. The activated negative sexual memories include memories of the event, distressing emotions and physiological responses, negative meanings, and behav- iours. Such distressing memories may become further nega- tively elaborated by post-event sexual and non-sexual distress- ing experiences. Activated negative sexual-related memories may start to function as a trigger to hypersexual behaviours, fan- tasies and urges. Pleasurable sexual experiences with consenting adults or other types of pleasurable sexual activities become encoded and stored in memory. Such memories consist of the sexual-arous- ing stimuli, the sexual activities and behaviours, the sexual emotional and physiological responses and the meanings at- tached to the activity. The activation of pleasurable sexual memories may act as a trigger to start to engage in positively reinforcing sexual activities or behaviours in the current situa- tion. Additional pleasurable sexual activities reinforce the sex- ual memory triggers. The pleasurable sexual memories may expand in terms of additional stimuli and responses that be- come associated with sexual pleasure. Some individuals feel so compelled by the urge to satisfy one’s sexual pleasure in the short-term, that the potential negative consequences are not cur- rently considered. Non-Sexual-Related Memories That Act as Triggers to Hypersexual Behaviors, Fantasies and Urges Various types of negative life experiences are associated with distressing emotions, physiological responses, dysfunctional coping behaviors and negative meanings that become encoded and stored in memory. The activation of unprocessed negative memories , or memories with excessively negative meanings (e.g., trauma, distressing interpersonal events e.g. bullying or conflicts, distressing medical conditions of self or others, loss of significant others etc.), leads to psychological distress. The activation of negative memories that lead to emotional distress may act as a trigger to start engaging in hypersexual behaviors, fantasies and/or urges. Negative or Dysf unctional Beliefs about Excessive Sexu al Behaviors It is proposed that negative interpretations of hypersexual behaviors, fantasies and urges contribute to the maintenance of the disorder. Hypersexual behaviors and fantasies, that lead to distress and negative consequences in ones functioning in important life areas (job, interpersonal, leisure etc.), may be interpreted as uncontrollable and as indications of that one is an incompetent individual. Entrenched beliefs that one cannot control one’s hypersexual behaviors, fantasies or urges contribute to the maintenance of hypersexual disorder. In addition, beliefs that one cannot cope adequately with negative emotions and dis- tress associated with daily endeavors, contribute indirectly to the maintenance of hypersexual disorder. This is because hy- persexual behaviors and fantasies are utilized as dysfunctional alternatives to adequate coping. An entrenched belief that an exposure to triggers of sexual fantasies or urges will inevitably lead to sexual behaviors, in- creases the risk to engage in the latter. If sexual behaviors lead to an increased risk to negative consequences (e.g. relationship, job, economic), and if such beliefs are correct, it may be im- portant to avoid such triggers for the time being, while devel- oping adequate coping strategies. The belief that excessive sexual behaviors, fantasies and urges are addictions is dysfunctional. Healthy sexual needs and behaviors are not disorders that people need to control and ab- stain from. Sexuality is a biological necessity (survival of the species) and a pleasurable activity at its best. The view that troubled couples must abstain from sexual activities with each other may lead to negative consequences for the relationship. The view that a couple must abstain from sex in a shaky rela- tionship because such an activity is viewed as an addiction may lead to a deterioration in the relationship, especially if it is the most pleasurable activity for the couple. Also, if a dysfunc tion- al sexual activity that is a bad habit is conceptualized as an addiction, the problematic sexual behavior may be attributed to a “disorder”, and not to the individuals own responsibility. Different types of negative interpretations of excessive sex- ual behaviors, urges and fantasies are usually associated with different types of concomitant emotional responses. Here are a couple of examples. The belief that hypersexual behaviours are dangerous (e.g., that they may lead to feared negative cones- quences) leads to anxiety and fear. The belief that sexual be- haviours, fantasies or urges are indications of that oneself is a bad person leads to shame. The belief that sexual behaviours, fantasies and urges are actions that harm others emotionally may lead to feelings of guilt. The belief that one’s sexual be- haviours has led to interpersonal loss (e.g., abandonment by partner) may lead to emot ions of sadness and grief. Sometimes such beliefs may be functional (if one abstains from engaging in sexual activities with negative consequences), and sometimes they are non-functional (only adding to a person’s emotional distress). Some individuals hold the belief that they must engage in sexual behaviors, fantasies or urges in order to feel good about themselves. Sexual behaviors are viewed as a means of coping (e.g. soothing oneself). Distressing situations or activated me- mories may trigger the belief that “I must engage in sexual activities in order to feel better”. That is, some individuals hold the belief that sexual behaviors and fantasies have an important soothing function when negative emotions are experienced. For example, boredom and loneliness may trigger such a belief. Boredom may trigger specific thoughts that sexual behaviors and fantasies are the only means to become stimulated in one’s otherwise dull and boring everyday life. Feelings of loneliness may trig ger specifi c thoughts that the only means to escape the loneliness in the present moment is to engage in sexual beha- viors, fantasies and urges. Some people hold the belief that sexual behaviors and fanta- sies is the most effective way to reduce stress (e.g., engage in cybersex during job time) or to reduce the negative emotional consequences of stress (e.g., go to a striptease club after work). The maintenance of such beliefs increases the risk that sexual behaviors and fantasies will continue to be used as effective stress-reducing coping strategies in the short-run. However, N. PAUNOVIĆ, J. HALLB ERG OPEN ACCESS such sexual behaviors and fantasies may also lead to harsh neg- ative consequences (e.g., job loss or relationship strains). Non-sexual related shame may trigger a belief that sexual behaviors or fantasies may effectively shut down the feelings of shame. Also, sexual behaviors and fantasies may be believed to be an indication of that oneself is a bad person, which leads to further shame. The urges to engage in sexual behaviors and fantasies may be stronger than shame-related beliefs and emo- tions. Shame-related beliefs about sexual behaviors and fanta- sies may express themselves in shame-attacks directed to one- self. It usually may consist of an internal repeating self-punish- ing dialogue with the content that oneself is a very bad person. The engagement in sexual behaviors and fantasies may trigger beliefs such as “I am filthy and despicable” and elicit feelings of shame. Shame may lead to a concealing response so that the individual hides his/her sexual behaviors and fantasies to others. There is a fear that being exposed to an engagement in sexual behaviors and fantasies will lead to verbal condemnation in line with the shame-related attacks on oneself. An individual may feel guilty for engaging in sexual beha- viors and fantasies (Gilliland, South, Carpenter, & Hardy, 2011). The guilt may be about the consequences of the sexual behaviors and fantasies, or about the sexual behaviors and fan- tasies themselves. To what extent does sexual-related guilt make sense? And to what extent does it constitute cognitive distortions? The answers to these questions are probably con- text-related. On the one hand, some sexual behaviors and fanta- sies may hurt other people emotionally (e.g., guilt is a logical response). On the other hand, engaging in some sexual beha- viors and fantasies may sometimes only be about one’s values. For example, watching porn may to one person be a normal activity. However, when one’s partner doesn’t approve or views such behaviors as infidelity, then there is a clash in values re- garding the specific sexual activity. Another negative belief is to deem such sexual activities as morally wrong. Such beliefs may cause distress in individuals for sexual behaviors that may be considered acceptable, or within the limits of normal sexual behavior for most people. Excessive sexual behaviors, fantasies and urges may be in- terpreted as indications of a psychological disturbance, i. e., that there is something seriously defective about oneself. Sexual behaviors and fantasies are behaviors that can be enacted on a continuum in terms of frequency, intensity and duration. Nega- tive beliefs about sexual behaviors and fantasies that are within the limits of acceptable sexual behavior for most people can lead to psychological distress and other negative consequences in important life areas. The belief that sexual behaviors, fanta - sies and urges are symptoms of a psychological disturbance, behaviors and reactions acceptable in society, may be dysfunc- tional. If an elevated frequency, intensity and duration of ac- ceptable sexual behaviors leads to psychological distress and decreased functioning in important life areas, then such beha- viors may be viewed as elevated normal sexual behaviors that need to be better controlled or decreased. The belief that pleasurable sexual behaviors and fantasies are positive, despite negative consequences to oneself and others (relationship, job, emotional, economic etc.), should be consi- dered dysfunctional. Infidelity may constitute excessively pleas- urable activities that are viewed very positively. However, if it hurts one’s partner and leads to disruptions in a significant rela- tionship, then positive beliefs about infidel sexual activities are dysfunctional. Also, pleasurable sexual behaviors and fantasies that take up too much time (e.g., cyberporn) may compromise other important engagements. If other important engagements become seriously compromised because time is wasted on sex- ual activities, then the positive beliefs about such activities should be considered dysfunctional in relation to the compro- mised engagements. Negative Interpretations of Stimuli That Function as Triggers to Excessive Sexual Behaviors Negative Beliefs and Interpretations of Negative Emotions Related to Current Situations as Triggers Unwanted negative emotional experiences may function as triggers to hypersexual behaviours. The content of negative beliefs and interpretations of current situations or stimuli are logically tied to specific emotional responses. Specific beliefs and interpretations and their emotional consequences may start to function as triggers to excessive sexual behaviors and fanta- sies. Situations that are interpreted as indications of that one has been violated in personal ways, or that one has been seriously hampered in achieving a personally important goal, often lead to emotions of anger. Situations that are interpreted as that one has no stimulating or meaningful activities to engage in may lead to emotions of boredom. Beliefs that oneself as inadequate, that other people are non-helpful or untrustworthy, and that the future is full of unattainable obstacles often lead to low mood, depressive-like emotions and sadness. The belief that specific situations or stimuli are dangerous leads to emotions of anxiety and fear. Stressful situations that are interpreted as too de- manding may lead to emotional stress responses. Negative un- wanted emotions such as anger, boredom, anxiety , fear, sadness and low mood may start to function as triggers to excessive sexual fantasies and behaviors. Negative Beliefs and Interpretations of Relationship-Related Situations and Problems as Triggers A partner that is believed to be too demanding may result in emotional distress. Such distress may act as a trigger to exces- sive sexual behaviors and fantasies. The belief that a partner is too demanding may relate to non-sexual or sexual issues. Be- liefs and interpretations of the partner as excessively demand- ing are subjective. They may reflect behaviors that may be viewed as more or less “objectively demanding” by outside observers. Subjective experiences of demanding partners may differ extensively with regard to what is deemed to be demand- ing, and the subjective threshold of what needs to happen for this subjective experience to be felt. Other contributing factors should be taken into consideration. Does the client have deficits in coping capabilities with regard to handling demanding situa- tions? Is the frequency, intensity and/or duration of a partners demands extensive (i.e., is a client’s experience realistic?)? Does the client give in to a partner’s demands due to a fear of being negatively evaluated? Do sexual behaviors and fantasies temporarily alleviate short-term sexual or non-sexual perceived demands from a partner? If a partner has less sexual interest or need than a client who wants to engage in sexual activities more often, this may result in a belief that one cannot meet one’s sexual needs with the partner. The client may start to engage in sexual behaviors and N. PAUNOVIĆ, J. HALLB ERG OPEN ACCESS fantasies without the partner (e.g., internet porn or sexual ac- tivities with other people). The partner may hold the belief that the client is a sex addict, or is inadequate in other ways (e.g., doesn’t care, isn’t interested in oneself, doesn’t listen etc.). Thus, negative responses from the partner with regard to sexual activities may trigger a belief that the partner is sexually in- adequate and lead to the exacerbation of sexual behaviors and fantasies without the partner. Entrenched beliefs that oneself is lonely and the emotional experience of loneliness may trigger an excessive engagement in sexual behaviors and fantasies. Entrenched beliefs of loneli- ness may be triggered by unprocessed memories of earlier neg- ative interpersonal experiences (e.g., abandonment or separa- tion experiences). Intimacy with others may be viewed as threatening because it may trigger beliefs of repeated aban- donment. A current partner may be viewed as non-trustworthy due to a fear that he/she is going to abandon oneself. In order to suppress such beliefs and fears, a client may start to engage in excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies. Consequently, the belief is maintained due to a lack of adequate cognitive and emotional processing. Since such sexual behaviors and fanta- sies suppress one’s fear of intimacy and abandonment tempora- rily, the dysfunctional beliefs of abandonment are maintained. However, a partner’s responses to dysfunctional sexual beha- viors and fantasies may lead to real abandonment in the long run if the partner finds such behaviors excessively distressing. Negative Interpretations of One’s Sexual Func tioning as Triggers The theme “porn impotence” has to do with the belief that oneself is sexually impotent with one’s partner. If a client is able to react sexually by other means (e.g., cybersex, sexual activities with others), then “I am porn impotent” is a faulty assumption. “Inability” to sexually react towards one’s partner may be due to alternative explanations. A couple of possible alternative explanations are presented next. First, a lack of sex- ual responses towards one’s partner may be due to sexual satia- tion as a result of other sexual behaviors and fantasies, sexual stimulation (e.g., masturbation), and resulting ejaculation or orgasm. Second, a lack of sexual responses towards one’s part- ner may be due to the fear that one’s partner sees oneself as sexually unattractive or inadequate. Third, a lack of sexual res- ponses towards one’s partner may be due to the client per- ceiving the partner’s physical appearance as unattractive or behaviors as sexually non-appealing. Fourth, relationship con- flicts and intimacy problems with the partner may lead to a diminished sexual interest towards the partner. Negative Beliefs and Interpretations of Sexual- and Non-Sexual Related Memories as Triggers Sexual pleasurable memories may be viewed as desirable and function as triggers to plan and engage in excessive sexual be- haviours and fantasies. By dysfunctional is meant any behav- iors and fantasies that lead to negative consequences to oneself and/or others (e.g., emotionally, legally, health-related, mone- tary etc.). Distressing sexual memories (negative sexual ex- periences, sexual assault etc.) may be interpreted neg atively and motivate an engagement in excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies. The function is to shut down the negative meaning and emotions associated with non-processed distressing sexual- relate d memories. Distressing non-sexual memories associated with excessively negative beliefs and interpretations may, when triggered, gen- erate psychopathology symptoms. Psychopathology symptoms may be negatively interpreted and lead to negative or dysfunc- tional beliefs about oneself, other people and the world. Nega- tive beliefs that are associated with negative or distressing non- sexual memories, contribute to the maintenance of psychopa- thology symptoms. The strategies that are used in order to get rid of these symptoms, in the form of sexual behaviors and fantasies, contribute in the maintenance of negative beliefs and interpretations. If excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies are continuously utilized in order to shut down psychopathology symptoms, then the individual doesn’t learn new alternative beliefs associated with one’s personal negative memories, and the role of sexual behaviors and fantasies in one’s psychopa- thology symptoms. Negative Interpretations of Inhibited Valued Memories as Triggers Distressing memories associated with negative beliefs and current distressing circumstances may inhibit valued memories associated with significant relationships, sexual experiences, job careers, leisure activities etc. Valued memories may be- come inhibited and more or less non-accessible. Such an inhibi- tion may lead to depressive symptoms such as an increased sense of meaninglessness, diminished interest in previously appreciated activities, decreased ability to feel positive emo- tions and diminished motivation to relate to other people. Such reactions may be negatively interpreted and lead to the devel- opment of dysfunctional beliefs such as (a) that one is unable to experience positive activities and emotions, or (b) negative beliefs about oneself, other people or the world. Such negative beliefs may become triggers of excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies. Minimization of Consequences of Excessive Sexual Behaviors and Fantasies as a Tr ig ger One kind of negative belief that can function as a trigger to excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies is the faulty thought pattern minimization. Minimization is defined as some people’s tendency to downplay the role of negative consequences of engaging in dysfunctional sexual behaviors and fantasies. The more distress or harm that is a consequence of sexual beha- viors and fantasies, the more dysfunctional minimization of these sexual behaviors and fantasies becomes. For example, if an individual ignores the risk of engaging in cybersex during work-time, and one’s employer finds out about such activities, job loss may follow. Or, if a spouse harbors excessively nega- tive beliefs about cybersex, relationship strains may follow when such activities are discovered. Precautionary measures may be initiated in order to minimize the risk of becoming dis- covered. However, if such negatively valued sexual behaviors and fantasies become discovered, negative consequences may follow. A client needs to learn in advance how it would feel to be faced with interpersonal, job or other significant negative consequences in one’s life as a direct result of one’s engage- ment in dysfunctional sexual behaviors. Excessive Sexu al Behaviors and Fantasies as Avoidance Behaviors Sexual behaviors and fantasies can have the following psy- N. PAUNOVIĆ, J. HALLB ERG OPEN ACCESS chological functions: (a) to inhibit distressing sexual and non- sexual memories and associated beliefs and interpretations, (b) to avoid current distressing sexual and non-sexual stimuli and associated beliefs and interpretations, and (c) to provide sexual pleasure and intimacy. Sexual behaviors and fantasies with such psychological functions may lead to the following: (a) prevent new corrective experiences during the retrieval of dis- tressing sexual and non-sexual-related memories and associated beliefs and interpretations, (b) prevent new corrective expe- riences related to coping with current distressing situations and associated beliefs and interpretations, and (c) lead to negative long-term consequences (e.g., relationships, monetary, health- related, job loss etc .). Avoiding Negative Memories Associated with Negative Beliefs and Interpretations by Engaging in Sexual Behaviors and Fanta si e s Grief due to the loss of a significant other may be avoided by an engagement in sexual behaviors and fantasies. This leads to a temporary relief from the grief. However, when the sexual behaviors and fantasies are halted the un-processed grief will re-emerge. This motivates the individual to continually re-en- gage in sexual behaviors and fantasies in order to shut down the grief. The long-term consequence may be a maintenance of non-processed grief. This may have a negative impact on cur- rent relationships and one’s sexual functioning due to depres- sive-related mood. Sexual behaviors and fantasies may have the function of avoiding or escaping from traumatic memories as part of PTSD symptoms (Howard, 2007; Robinson, 1999). The function of sexual behaviors and fantasies may be to prevent the activation of traumatic memories (i.e., avoidance responses), or to shut down activated traumatic memories (i.e., escape responses). Current trauma memory triggers function as signals to start to engage in sexual behaviors and fantasies in order to prevent the activation of traumatic memories or to shut down activated trauma memories. People who have been severely bullied earlier in life may suffer severe psychological consequences (e.g., depression, negative self-view etc. ). The activation of unprocessed bullying memories that are related to excessively negative beliefs may be avoided by an engagement in sexual behaviors and fantasies. If distressing bullying memories are activated they may be shut down by an excessive engagement in sexual behaviors and fantasies. Avoiding Negative Emotions Triggered by Current Circumstances with Sexual Beha viours and Fantasies Current circumstances may be such that an individual l ives a lonely life. Sometimes this may be due to a job loss, relation- ship break-up or other reasons. Feelings of loneliness may be avoided by engaging in hypersexual behaviors and fantasies. In order to hold feelings of loneliness at bay in the short-term one has to constantly engage in hypersexual behaviors and fantasies. If the circumstances don’t change, the function of the sexual behaviors and fantasies may be maintained. Sexual behaviors and fantasies may be utilized as relaxation strategies in response to stress behaviors. This means that sex- ual behaviors and fantasies may indirectly maintain stress be- haviors by reducing the short-term negative stress-related con- sequences. Furthermore, sexual behaviors and fantasies may be an avoidance strategy to perceived or real demands, contribut- ing to the procrastination of important activities (e.g., job, in- terpersonal, other endeavours). Sexual behaviors and fantasies may constitute functional responses to relationship-related dissatisfaction. Dissatisfac- tions may stem from an impoverished sexual life with the part- ner, verbal conflicts, distressing demands from the partner, loss of sexual interest from the partner or other types of relationship problems. Sexual behaviors and fantasies as coping strategies don’t learn the individual to cope with the real problems in the relationship. It only leads to a temporary relief from the emo- tional consequences of the relationship issues. Some individuals harbor an irrational fear of intimacy with other people (e.g., one’s partner). An engagement in certain sexual behaviors and fantasies may keep such fear at bay. Sexual behaviors or fantasies may have the function of soothing physical pain caused by physical injuries. People who have irrational fears of being abandoned may handle this fear by temporarily engaging in certain sexual be- haviors and fantasies. This temporarily soothes or decreases the fear of abandonment. Emotions of sadness and depressive-like sy mptoms m ay be a response to current circumstances or due to the activation of unprocessed distressing memories associated with negative beliefs. Such emotions may be undesirable and coped with by an engagement in sexual behaviors and fantasies that tempora- rily inhibit feelings of sadness and depressive-like symptoms. Loss of significant others due to e.g. terminal medical condi- tions or traffic accidents leads ordinarily to acute grief reactions, and sometimes to posttraumatic stress symptoms. The natural grief process may be halted if the individual starts to engage excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies in order to avoid ex- periencing the grief. In order to keep acute grief out of one’s immediate consciousness and experience, one must constantly engage in sexual behaviors and fantasies. Anger may constitute a response to a perceived threat (e.g., phys i c a l, social, psyc hological etc.), a means to cope with neg- ative events or emotions, or a consequence of negative inter- pretations of other people’s or one’s own behavior as unfair etc. Anger may be an undesirable emotion that can be temporarily suppressed by an engagement in sexual behaviors and fantasies. Guilt involves interpretations of one’s own behaviors or lack of actions that is thought to have led to the occurrence of nega- tive events. Shame consists of beliefs about one’s character as completely bad (i.e., an excessively negatively characterologi- cal view of oneself). Guilt and shame may be so distressing and undesirable that an individual starts to engage in excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies. This is done in order to shut down emotions and cognitions associated with guilt or shame. However, this is a temporary solution since the guilt and shame is not adequately processed. Consequently, it will re-emerge back when the sexual behaviors and fantasies are halted. In addition, sexual behaviors and fantasies may generate addition- al guilt and shame if these actions are deemed to be a wrong- doing. Such beliefs further exacerbate the guilt and shame. Pleasurable Sexual A ctivities That Lead to Negative Consequences Sometimes the dysfunctionality of sexual behaviors and fan- tasies are solely determined by the negative consequences asso- N. PAUNOVIĆ, J. HALLB ERG OPEN ACCESS ciated with such behaviors. Negative consequences may be related to one’s own beliefs about the specific sexual behaviors and fantasies (e.g., guilt or shame). Or negative consequences may be related to negative responses from significant others, monetary loss or negative job consequences. The short-term pleasurable sexual engagements may hinder an individual from reflecting upon the possible real-life damaging consequences as a result of such behaviors. Consequences of E xcessive Sexual B ehaviors vs. Developing Healthy Coping Strategies The Shut-Down of Distressing Memories Associated with Negative Beliefs Excessive sexual behaviours and fantasies may maintain dis- tressing memories associated with negative beliefs if the former are functionally related to the latter. This may be due to the following reasons. First, there is a lack of adequate cognitive and emotional processing of issues that the distressing memo- ries and associated beliefs represent. Second, there is no focus on to solving real life problems, i.e. functional coping behaviors have not been developed or are not applied to primary trouble- some situations. When excessive sexual behaviours and fanta- sies are halted the avoided psychological or real life problems have the opportunity to become available in one’s conscious- ness. Alternative healthy coping strategies must be utilized in relation to one’s non-processed distressing memories. If this is not done, the individual may re-engage in the only coping be- havior that has seemed to work in shutting down distressing memories associated with negative beliefs: sexual behaviours and fantasies. Hence, the underlying psychological problems and life issues will be maintained as well as the dysfunctional sexual behaviors and fantasies. Coping with Stress Excessive sexual behaviours and fantasies may have two primary functions with regard to coping with stress: (a) to pro- crastinate from important engagements, activities or duties, or (b) to handle the consequences of primary stress behaviors (i.e., a soothing function). Unless the individual develops healthy strategies on how to deal with primary stress situations it their consequences, there is a risk that the excessive sexual behav- iors and fantasies will be maintained. Coping with Negative Emotions in Gen eral When excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies fulfil an avoi- dance function in relation to negative emotions, the individual must develop alternative coping strategies in order to handle negative emotions and the associated beliefs and life problems. If alternative coping strategies are developed, or existing cop- ing abilities are applied, the function of excessive sexual be- haviors and fantasies cease to hold their sole grip on the indi- vidual. This is so because other more healthier coping alterna- tives become possible. Coping with the Aftermath of Interpersonal Distress When excessive sexual behaviours and fantasies fulfil a soothing function that decreases interpersonal-related emotional distress (e.g., conflicts with a partner), it is important to develop more functional coping strategies in order to handle the specific interpersonal problems. If this is not accomplished, the client will continue to engage in excessive sexual behaviours and fantasies in order to sooth the aftermath of interpersonal prob- lems. Experiencing Dysfunctional Sexual Pleasure When sexual pleasurable activities lead to negative cones- quences (e.g., interpersonal strain with a partner, job or finan- cial difficulties etc.), the sexual activities are considered to be dysfunctional due to their negative consequences. Here it is crucial to develop consequential thinking that can inhibit im- pulses related to engagements in dysfunctional sexual behaviors and fantasies. Learning to reflect upon realistic negative con- sequences as a result of an engagement in dysfunctional sexual behaviours and fantasies is essential in order to be motivated to abstain from such destructive behaviours. Behavior-Memory Inhibition: Sexual Behaviors as Inhibitors o f ( A) Distressing Memor ies Associated with Negative Beliefs, and (B) Current Distressing Stimuli It is argued that sexual behaviors, associated with positive or functional beliefs that are in opposite to dysfunctional or nega- tive beliefs, may be able to inhibit the latter. Inhibition of Distressing Sexual-Related Memories Distressing or dysfunctional sexual-related memories may constitute emotionally non-processed memories. In the last section the view was put forward that sexual behaviors may function as avoidance behaviours. That is, those sexual behav- iors may hinder adequate emotional and cognitive processing of distressing sexual-related memories associated with negative beliefs. On the other hand, sexual behaviors may in some cir- cumstances fulfil the opposite function. That is, sexual behav- iors may in some circumstances therapeutically inhibit emo- tions associated with distressing sexual-related memories and lead to an increased psychological and sexual well-being. The Inhibition of Distressing Relationship-Related Memories Associated with Negative Beliefs Sexual behaviors may in some circumstances function as in- hibitors to distressing relationship memories associated with negative beliefs. In the previous section the view was presented that sexual behaviors may constitute dysfunctional avoidance behaviors to problematic relationship issues that need to be resolved. However, sometimes sexual behaviors may have a positive function in some relationships, and may inhibit some strains associated with some types of relationship difficulties. Inhibition of Distressing Non-Sexual Memories Associated with Negative Beliefs Sexual behaviors can likewise function as inhibitors to dis- tressing non-sexual related memories associated with negative beliefs. Once again, in this context sexual behaviours may have a positive function insofar as they may therapeutically inhibit distressing memories associated with negative beliefs. N. PAUNOVIĆ, J. HALLB ERG OPEN ACCESS Inhibition of Emotional Responses to Current Distressing Stimuli Sexual behaviors may in some circumstances be viewed as positive coping strategies. If such behaviors have a soothing or relaxing function, and if they don’t lead to negative cones- quences in important life areas, then it is up to the individual who engages in such behaviors to decide whether to engage in them or not. Memory-Memory Inhibition: Sexual Fantasies and Other Valued Memories as Inhibitors of Dysfunctional Memories Associated with Negative Beliefs Pleasurable sexual fantasies and other valued memories may function as inhibitors to distressing dysfunctional memories associated with negative beliefs. The distressing memories as- sociated with negative beliefs may constitute distressing sex- ual memories, negative relationship-related memories or other distressing non-sexual related memories associated with nega- tive beliefs. If the pleasurable sexual or other valued memories are associated with positive or functional beliefs, and if the latter constitute strong evidence against dysfunctional or nega- tive beliefs generated by activated negative or distressing memories , then a healthy psychological functioning will de- velop. Behavioral Activ ation of Valued Activities as Inhibitors of Sexual Behaviors and Distressing Memories An increased engagement in valued behavioral activities that are related to meaningful relationships, jobs, leisure activities can acquire inhibiting functions. That is, valued behavioral activities may inhibit dysfunctional sexual behaviors, fantasies and urges. Such activities may also function as inhibitors to distressing sexual and non-sexual memories associated with negative beliefs. For this to occur, it is important that the ex- periences of valued behavioral activities constitute strong evi- dence that support positive or functional beliefs about oneself, other people and the world. It is also important that the positive or functional beliefs are relevant and strong enough so that they can inhibit the negative or dysfunctional sexual- and non-sexual related beliefs. Discussion In the present article hypersexual disorder is conceptualized with the behavioral-cognitive inhibition theory. It is argued that excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies may become asso- ciated with dysfunctional negative or positive beliefs. Next, it is argued that excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies have dys- functional psychological functions. First, their function is to help the individual to cope with distressing situations or memo- ries that are associated with negative or dysfunctional beliefs. Second, sexual behaviors may sometimes only be dysfunctional due to their negative consequences for oneself or other people. Next, it is also argued that sexual behaviors and fantasies in some circumstances may constitute functional behaviors that may inhibit distressing memories associated with negative be- liefs, and also current distressing situations. The article has not focused on biologically related contribut- ing factors such as sexual deprivation and satiation. Excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies are more effective in suppressing or inhibiting negative or distressing emotions and memories when an individual is in a state of sexual deprivation. That is, if an individual has not engaged in sexual activities for a long enough time, one’s natural biological sexual urges become stronger. Hence, when an individual uses sexual activities in a sexually deprived state, he or she will respond emotionally stronger to the sexual activity. Consequently, the stronger the sexual emotional response, the more effectively it will be able to inhibit distressing emotional responses. Conversely, if the individual has engaged excessively in sexual activities and fantasies, and ejaculated or had multiple orgasms for a short period of time, one’s natural sexual biological satiation will lead to decreasingly pleasurable sexual emotional responses. In the latter case, an engagement in sexual behaviors and fantasies when an individual is in a state of sexual satiation, will result in a diminished capacity to suppress negative emotional responses associated with distressing sexual and non-sexual problematic life issues. A cognitive-behavioral treatment for hypersexual disorder, based on the behavioral-cognitive inhibition theory, should in- clude the following components: • The identification of triggers that set of excessive sexual behaviours and fantasies (whether sexual or non-sexual current stimuli or distressing memories associated with ne- gative beliefs); • The topography of specific excessive sexual behaviours and fantasies; their frequencies, duration and intensity; • The context in which excessive sexual behaviors and fanta- sies occur: where, with whom, other important aspects of the situation; • The psychological function of excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies: to handle distress (negative reinforcement) and/or to get pleasure (positive reinforcement); • The consequences (both short- and long-term) that follow due to the engagement in excessive sexual behaviours and fantasies; • The idiosyncratic interpretations and beliefs of triggers, hypersexual behaviours and fantasies, and consequences; • The inhibition of valued memories and how to through be- havioral and cognitive techniques de-inhibit the valued memories ; • The maintenance of dysfunctional respondent-functional- beliefs memories. The behavioral-cognitive inhibition theory provides a broad and focused conceptualization that can target relevant main- taining factors in hypersexual disorder. The behavioral-cogni- tive inhibition theory is able to tie together all these problem areas into a coherent framework. Cognitive therapy that has been developed for the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders (Beck, Emery, & Green- berg, 1985; Beck , Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) may be adapt- ed and utilized in the treatment of excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies. Interpretations and negative beliefs about exces- sive sexual behaviours and fantasies, and sexual and non-sexual triggers, may be crucial to target in treatment when they con- tribute to the maintenance of the hypersexual disorder. The focus on beliefs associated with triggers of excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies is important in order to defuse the im- pact that triggers have on the urge to engage in excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies. The focus on beliefs about excessive  N. PAUNOVIĆ, J. HALLB ERG OPEN ACCESS sexual behaviors and fantasies themselves may include both thoughts about the function they serve as well as negative be- liefs that may contribute to the maintenance of hypersexual behaviors and fantasies. Behavioral techniques should focus on two important aspects. First, on the function of the excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies. Second, on behavioral activation and developing com- petencies that will defuse the impact of triggers that set of ex- cessive sexual behaviors and fantasies. Imagery techniques can be utilized in order to strengthen memories that are incompatible to negative or dysfunctional memories (Holmes, 2007; Paunovic, 2011). Imagery techniques may be more effective in changing negative cognitions that maintain excessive sexual behaviors and fantasies than cogni- tive techniques. Imagery may be more effective in eliciting emotions that provide corrective experiences than verbal tech- niques. REFERENCES Adams, K. M., & Robinson, D. W. (2001). Shame redu ction, affect re- gulation, and sexual boundary development: Essential building blocks of sexu al addiction treatment. Sexual Addiction & Treatment , 8, 23-44. Beck, A. T., Emery, G., & Greenberg, R. L. (1985). Anxiety disorders and phobias: A cognitive perspective. New York: Basic Books. Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depress ion. New York: Guilford Press. Gilliland, R., South, M., Carpenter, B. N., & Hardy, S. A. (2011). The roles of shame and guilt in hypersexual behavior. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 18, 12-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2011.551182 Giugliano, J. (2006). Out of control sexual behavior: A qualitative investigation. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 13, 361-375. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10720160601011273 Hardy, S. A., Ruchty, J. , Hull, T. D., & Hyde, R. (201 0). A preliminary study of an online psychoeducational program for hypersexuality. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 17, 247-269. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2010.533999 Holmes, E. A., Arntz, A., & S mucker, M. R. (2007 ). Imagery rescript- ing in cognitive behavior therapy: Images, treatment techniques and outcomes. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychia- try, 38, 297-305. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.10.007 Howard, M. D. (2007). Escaping the pain: examining the use of sex- ually compulsive behavior to avoid the traumatic memories of com- bat. Sexual addiction and compulsivity, 14, 77-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10720160701310443 Kingston, D. A., & Firestone, P . (2008). Problematic hypersexuality: A review of conceptualization and diagnosis. Sexual Addiction & Com- pulsivity, 15, 284-310. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10720160802289249 Klontz, B. T., Garos, S., & Klontz, P. T. (2005). The effectiveness of brief multimodal experiential therapy in the treatment of sexual ad- diction. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 12, 275-294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10720160500362488 Leahy, R. L., & Tirch, D. D. (2008). Cognitive behavioral therapy for jealousy. International Jour nal of Cognitiv e Therapy, 1, 18-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2008.1.1.18 Paunović, N. (2010a). Behavioral-cognitive inhibition theory. Lecture Presented at the 11th International Conference of the International Association for the Treatment of Sexual Offenders. Oslo, Norway. Paunović, N. (2010b). Behavioral-cognitive inhibition theory: Concep- tualization of post-traumatic stress disorder and other psychopathol- ogy disorders . Psychology, 1, 349-366. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2010.15044 Putnam, D. A. (2000). Initiation and maintenance of online sexual compulsivity: Implications for assessment and treatment. Cyber Psychology & Behavior, 3, 553-563. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/109493100420160 Robinson, D. W. (1999). Sexual addiction as an adaptive response to post-traumatic stress disorder in the African American community. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 6, 11-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10720169908400175 Samenov, C. P. (2011). What you should know about hypersexual dis- order. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 18, 107-113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2011.596762 Yoder, V. C., Virden, T. B., & Amin, K. (2005). Internet pornography and loneliness: An association? Sexual Addictio n & Compulsivity, 12, 19-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10720160590933653 Paunovic, N. (2011). Exposure inhibition therapy as a treatment for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: A controlled pilot study. Psy- chology, 2, 605-614. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2011.26093

|