78 M. SIGAROUDINIA ET AL.

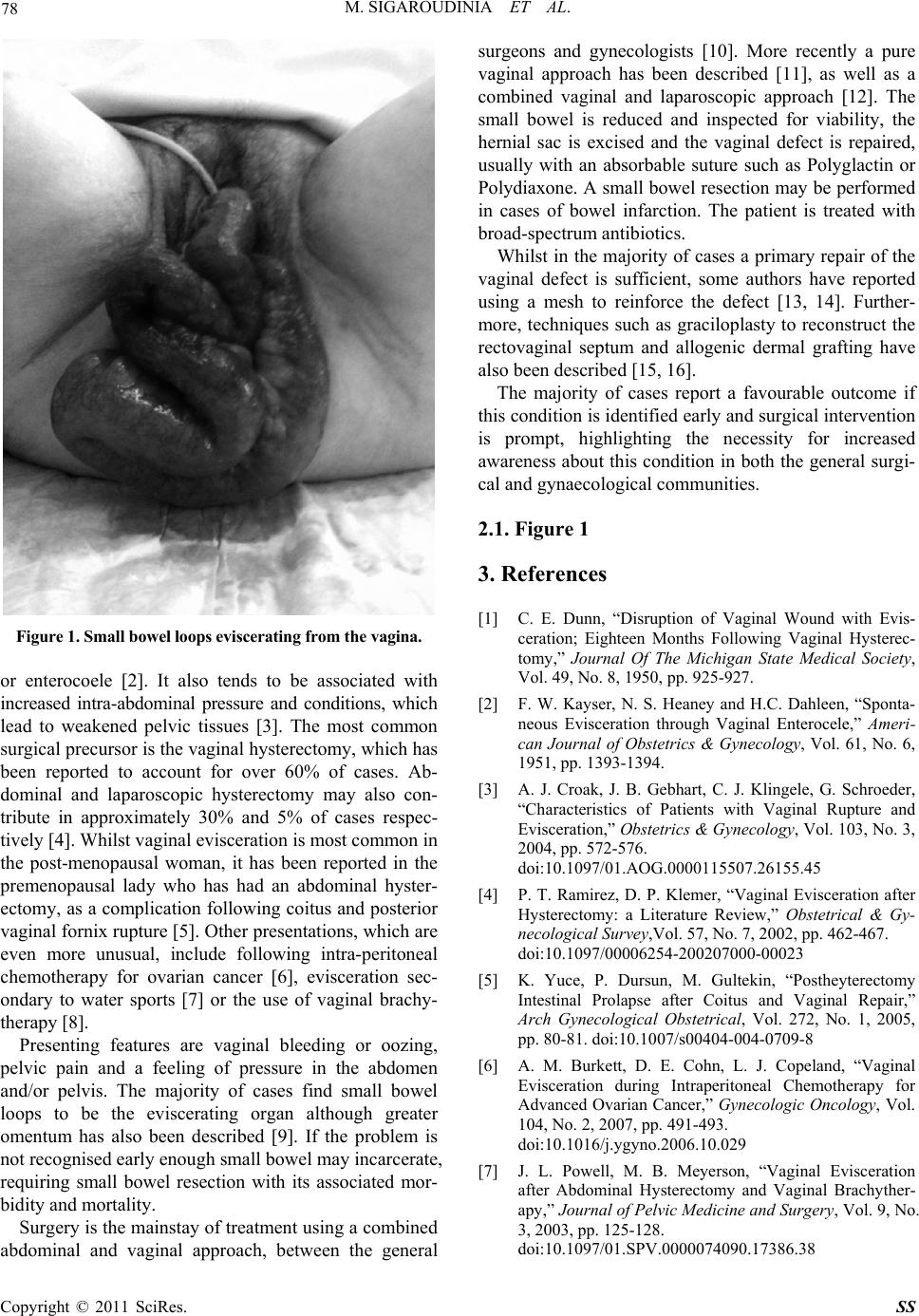

Figure 1. Small bowel loops eviscerating from the vagina.

or enterocoele [2]. It also tends to be associated with

increased intra-abdominal pressure and conditions, which

lead to weakened pelvic tissues [3]. The most common

surgical precursor is the vaginal hysterectomy, which has

been reported to account for over 60% of cases. Ab-

dominal and laparoscopic hysterectomy may also con-

tribute in approximately 30% and 5% of cases respec-

tively [4]. Whilst vaginal evisceration is most common in

the post-menopausal woman, it has been reported in the

premenopausal lady who has had an abdominal hyster-

ectomy, as a complication following coitus and posterior

vaginal fornix rupture [5]. Other presentations, which are

even more unusual, include following intra-peritoneal

chemotherapy for ovarian cancer [6], evisceration sec-

ondary to water sports [7] or the use of vaginal brachy-

therapy [8].

Presenting features are vaginal bleeding or oozing,

pelvic pain and a feeling of pressure in the abdomen

and/or pelvis. The majority of cases find small bowel

loops to be the eviscerating organ although greater

omentum has also been described [9]. If the problem is

not recognised early enough small bowel may incarcerate,

requiring small bowel resection with its associated mor-

bidity and mortality.

Surgery is the mainstay of treat ment using a combined

abdominal and vaginal approach, between the general

surgeons and gynecologists [10]. More recently a pure

vaginal approach has been described [11], as well as a

combined vaginal and laparoscopic approach [12]. The

small bowel is reduced and inspected for viability, the

hernial sac is excised and the vaginal defect is repaired,

usually with an absorbable suture such as Polyglactin or

Polydiaxone. A small bowel resection may be performed

in cases of bowel infarction. The patient is treated with

broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Whilst in the majority of cases a primary repair of the

vaginal defect is sufficient, some authors have reported

using a mesh to reinforce the defect [13, 14]. Further-

more, techniques such as graciloplasty to reconstruct the

rectovaginal septum and allogenic dermal grafting have

also been descr i b ed [15, 16].

The majority of cases report a favourable outcome if

this condition is iden tified early and surgical interv ention

is prompt, highlighting the necessity for increased

awareness about this condition in both the general surgi-

cal and gynaecological communities.

2.1. Figure 1

3. References

[1] C. E. Dunn, “Disruption of Vaginal Wound with Evis-

ceration; Eighteen Months Following Vaginal Hysterec-

tomy,” Journal Of The Michigan State Medical Society,

Vol. 49, No. 8, 1950, pp. 925-927.

[2] F. W. Kayser, N. S. Heaney and H.C. Dahleen, “Sponta-

neous Evisceration through Vaginal Enterocele,” Ameri-

can Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Vol. 61, No. 6,

1951, pp. 1393-1394.

[3] A. J. Croak, J. B. Gebhart, C. J. Klingele, G. Schroeder,

“Characteristics of Patients with Vaginal Rupture and

Evisceration,” Obstetrics & Gynecology, Vol. 103, No. 3,

2004, pp. 572-576.

doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000115507.26155.45

[4] P. T. Ramirez, D. P. Klemer, “Vaginal Evisceration after

Hysterectomy: a Literature Review,” Obstetrical & Gy-

necological Survey,Vol. 57, No. 7, 2002, pp. 462-467.

doi:10.1097/00006254-200207000-00023

[5] K. Yuce, P. Dursun, M. Gultekin, “Postheyterectomy

Intestinal Prolapse after Coitus and Vaginal Repair,”

Arch Gynecological Obstetrical, Vol. 272, No. 1, 2005,

pp. 80-81. doi:10.1007/s00404-004-0709-8

[6] A. M. Burkett, D. E. Cohn, L. J. Copeland, “Vaginal

Evisceration during Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for

Advanced Ovarian Cancer,” Gynecologic Oncology, Vol.

104, No. 2, 2007, pp. 491-493.

doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.10.029

[7] J. L. Powell, M. B. Meyerson, “Vaginal Evisceration

after Abdominal Hysterectomy and Vaginal Brachyther-

apy,” Journal of Pelvic Medicine and Surgery, Vol. 9, No.

3, 2003, pp. 125-128.

doi:10.1097/01.SPV.0000074090.17386.38

Copyright © 2011 SciRes. SS