Psychology 2014. Vol.5, No.2, 134-141 Published Online February 2014 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2014.52021 OPEN ACCESS Comparison of Partner Choice between Lesbians and Heterosexual Women Vivianni Veloso, Regina Brito, Cibele Nazaré da Silva Câmara Post-Graduation Program in Theory and Behavior Research, Federal University of Para, Belém, Brazil Email: hellenvivianni@bol.com.br Received November 20th, 2013; revised December 18th, 2013; accepted January 14th, 2014 Copyright © 2014 Vivianni Veloso et al. This is an open access articl e distributed und er the Creative Commons Attribution License, which pe rmits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved f or SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Vivianni Veloso et al. All Copyrigh t © 2014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. Studies comparing preferred partner selection between homosexual and heterosexual women have shown that homosexual women exhibit patterns of choice that resemble both the heterosexual men and hetero- sexual women. This intersection between groups indicates that some characteristics valued by women may be intermediate between homosexual men and heterosexual women. This selection appears to be in- fluenced by the type of relationship of the individual. Heterosexual women emphasize preference for characteristics related to physical health in short-term relationships. In long-term relationships, the em- phasis is on the characteristics of good provision of resources and emotional investment. This study aimed to compare the preferences of the two groups of women in partner choice in the types of relationships mentioned. The participants were 100 homosexual and 55 heterosexual women in reproductive period. A questionnaire was used to collect information. The participants were contacted by indication, in LGBT bars or associations. There were similarities between groups with regard to the choices they made. The Macro-category attachment formation was requested more in the long-term and good genes was more ap- preciated in the short term. However, in both short and long term relationships homosexuals appreciated good genes more than heterosexuals. Heterosexual women valued good provision of resources more in long-term relationships. The reasons for these differences could be several, starting from social aspects all the way up to biological ones. Keywords: Partner Selection; Homosexuality; Women Introduction Researchers in the field of Evolutionary Psychology have been conjecturing for a long time now about the existence of psychological mechanisms at work in the selection of partners (Buss, 1989, 1995, 2006; Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Buss & Sha- kelford, 2008). Due to the difference in parental investment between genders, men and women display significant differ- ences, like the high valuation of good provision of resources and attachment formation among women, and the high apprais- al of physical attributes among men (Altafim, Lauandos, & Caramaschi, 2009; Buss, 1989, 1995, 2006; Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Buss & Shakelford, 2008; Campos, 2005; Carneiro, 1997; Castro, 2009; Covolan, 2005; Cruz, 2009; Fiore, 2010; Furn- ham, 2009; Greengross & Miller, 2008, Hattori, 2009; Lippa, 2007; Sadala, 2005; Stewart, Stinnett, & Rosenfelt, 2000). However, the idea of a rigid neural structure or of a behavior triggered by a specific stimulus, does not find any support in the realm of psychological mechanisms, for the flexibility of the human mind seems to be cru cial in order to b e able to adapt to different environments (Gangestad, Haselton, & Buss, 2006; Oliva, Otta , Bussab, Lopes, Yamamo to, & Moura, 2006). It is thus generally agreed upon that the psychological mechanisms at work in the choice of partners are constantly influenced by conditions of various kinds, such as, ecological (incidence of pathogens), social (socio-economic characteristics of a region) and individual (physical properties, age, childhood experiences, menstrual cycle) that, as a result, end up determining the kind of sexual strategy an individual will adopt more often (Buss, 2006; Buss & Shakelford, 2008; Fisher, 1995; Gangestad & Simpson, 2000; Pawlowski, 2000; Schmitt, 2006; Stone, Shack- elford, & Buss, 2008). The present study will give emphasis to the sexual strategies in the short and long-term. These also influence the preference of attributes among women (Campos, 2005; Castro, 2009; De- Waal & Maner; 2008; Lucas, Koff, Gro ssmit h , & Migliorini, 2011). Generally speaking, heterosexual women appear to be more attracted to attributes that relate to good genetic quality in short-term relationships (Campos, 2005; De Waal & Maner; 2008; Lucas et al., 2011). Evolutionary Psychology explains this penchant on the premises of the low probability that the offspring of this casual sexual intercourse will be able to count on care from the father, what would imply in a high cost of female investment in that child (Schmitt, 2005). So, our ancestors that distinguished signs of good genetic qualities in the casual partner and handed down to their child the good genetic characteristics of the father, increased its probability of survival in the event of the desertion of the father. V. VELOSO ET AL. OPEN ACCESS Successful choices in short-term sexual encounters probably selected the female psychological choice mechanisms focused upon genetic quality, in circumstances of scarcity of resources and partners (Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Buss & Shakelford, 2008; Schmitt, 2005). In long-term relationships, heterosexual women have a ten- dency to prioritize attributes related to good provision of re- sources and emotional investment (Buss & Shakelford, 2008; Schmitt, 2005; Stewart et al., 2000), and this importance is seemingly due to the high probability of the presence of father- ly care during the development of the offspring (Borrione & Lordelo, 2005; Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Schmitt, 2006). Other conditions, like acc e ss, or the lack thereof, to resources by the female, may define the degree of appreciation of poten- tial partners that signal attributes related to these conditions. In other words, when there is a shortage of resources, there may be an increased preference for partners with attributes that in- dicate greater likelihood of meeting this shortage (Gangestad & Simpson, 2000; Lippa, 2007; Wood & Eagle, 2007). According to Lippa (2007) women in countries where they have no need for their partners for subsistence showed that they prioritize attributes related to the strengthening of the relationship. As stated, many factors may be related to differences in how women select partners: the kind of sexual strategy, access to resources, and—why not—sexual orientation. Most data on women’s partner selection come from studies with heterosexual women. There are few studies that compare the criteria for choosing partners among homosexual and hete- rosexual women in literature. The studies that take on to this kind of comparison, report likeness and disparity between the preferences of these women (Bailey, Gaulin, Agyei, & Gladue, 1994; Corrêa, 2011; Ha, van den Berg, Engels, & Lichtwarck- Aschoff, 2012; Lippa, 2007; Lucas et al., 2011; Kenrick, Keef, Brya n, Barr, & Brown, 1995; Russock, 2011; Smith, Konik, & Tuve, 2011). The reasons for the differences in the choice of partners seem not to have been well understood, as yet. Even fewer studies have been conducted about the prefe- rences of homosexual women in short and long term relation- ships. Up to now, only Lucas et al. (2011) did research with lesbians in short and long-term relationships. Smith, Konik and Tuve (2011) stated that their study was geared towards long- term relationships. In the remaining researches, the results of which are listed below, there’s no mention about the kind of relationship. In all the studies the sexual orientation was indi- cated through self-classification and in none of these the eco- nomic level was stated (except on the whole, mixing men and women), or financial independence of the partakers, with the exception of the research conducted by Ha et al. (2012), which reports that most of the participants were employed, 68% of the homosexual women and 71% of the heterosexual women. Lip- pa (2007) generally describes his sample (including men) as “well educated”, for 57% held a master’s degree or had a col- lege education. Lucas et al. (2011) worked with college stu- dents. The rest does not mention the education level of their participants. A summary of the researches that will be de s cribe d below, can be observed in Table 1. Generally speaking, the similarities between homosexual and heterosexual women identified by the authors were in line with evolutionary forecasts. They resemble in the following aspects: little interest in sex with no commitment, high concern with emotional infidelity, low importance to the partner’s physical attractiveness—in researches where the type of relation is un- defined (Bailey et al., 1994). The low importance given to phy- sical attractiveness has a different outcome in another research, as we will see below (Ha et al., 2012). Other similarities between the two groups of women are: preference for older partners (Bailey et al., 1994; Kenrick et al., 1995) and general alikeness for character traits (like honesty and values) (Lippa, 2007). There is also greater appreciation of physical attributes when the relationship is in the short-term (Corrêa, 2011; Lucas et al., 2011), as specified in research with only heterosexual women (Campos, 2005; Castro, 2009; De- Waal & Maner, 2008). The results of studies like Bailey et al. (1994) and Russock (2011) show that there is no difference in the valuation of the term “physical attractiveness” between the two groups of wo- men in the search for a partner. Only the results of Ha et al. (2012) pointed out, through a questionnaire, that the term “at- tractive look” was more valued by heterosexual women than by homosexual ones. Within the comparison between the two groups of women, these and other researches revealed that ho- mosexual women appear to be less demanding of partners with resources (Bailey et al., 1994; Russock, 2011; Smith, Konik, & Tuve, 2011) and more attracted by visual sexual stimuli (por- nographic products, for example) (Bailey et al., 1994). Accord- ing to Bailey et al. (1994) the relatively high responsiveness to sexual stimuli in men is related to the increased probability of reproduction, given that, for men, being always ready for sexual and reproductive activities does not cost as much as it does for women. For a woman it wouldn’t be very beneficial if she were extremely sensitive to these stimuli, since she’s more selective due to her big investment in her offspring (Bailey et al., 1994). It’s important to highlight that in the study conducted by Russock (2011), homosexual women are more attracted by resources than heterosexual men, and in the research by Bailey et al. (1994) they have measures of valuation that are equivalent to those of men of both kinds of sexual orientation. These wo- men may have preferences that take on levels that are halfway between heterosexual women and men. Kenrick et al. (1995) account that, w hen asked a bout the mi - nimally acceptable age of a partner, homosexual women tend to be more lenient towards this minimum as they grow older, which differs from what’s happening in the heterosexual camp. This is not to say that homosexual women do not value older partners as heterosexual women do, or at a level closer to theirs. Nor does it mean that homosexual women value youth as much as men do. According to Russock (2011), this differential as- pect is also present on an intermediary level of preference for age between men and heterosexual women, as does the valua- tion/devaluation of resources and responsiveness to sexual sti- muli (Ba iley et al., 1994; Russock, 2011). Russock (2011) explains that the differences found in his re- search are due to the differences in need between women of the two sexual orientations. For heterosexual women, the choice of a partner with resources and more advanced age could be an element that maximizes reproductive success. This conclusion seems to prove the part played by ecological components in the modulation of phylogenetic selection mechanisms of partners as such. Lippa (2007) reports that homosexual women attach more value to the intelligence of the partner than do heterosexual women, and these latter value more aspects like ambition, trust and resources—or proof of the potential to get resources. The demand for honesty was higher among homosexuals (Smith,  V. VELOSO ET AL. OPEN ACCESS Table 1. Similarities and differences between homosexual and heterosexual women in different studies. Authors Similariti es between homosexual and heterosexual women Differenc es between homosexual and heterosexual women Bailey et al. (1994) Little interest for sex without comm itme nt/More concerned with emotional infidelity/Less importanc e to the physical attractiveness of the partner/Preference for older partners. Homosexuals showed less interest for partners with resources and responded more positively to vis ual sexual stimuli. Kenrick et al. (1995) Acceptance of older partners on the same level. The older the homosexual woman, the more she’s lenient about the minimum age a partner should have. Lippa (200 7) General appreciation for character traits/Low importance to Homosexuals consider ed the partne r ’s intelligence to be more import ant than did the heterosexuals/Heterosexuals attached much more value to ambition, trust and money. Lucas et al. (2011) Higher preference for physical attractiveness in short-term relationships, compared to lon g-term. Russock (2 011) prefer older partners and with more resources. Smith et al. (2011) Heterosexuals attach more importance to financial status and security/Homosexuals of both types demanded more sincerity. Ha et al. (2012) In the questionnaire, heterose xual wome n attache d more value to attractiveness , completed education, high salary and ambition than did Note: Dashes within cells indicate that these data were not mentioned. In all studies the women were aged between 18 and 40 years, with the exception of the studies by Kenrick et al. (1995) and H a et al. (2012) in which ages were up to 50 and 71 years, respectively. Konik, & Tuve, 2011). According to Bailey et al. (1994) certain differences between homosexual and heterosexual women are not purely social. If the form of early socialization among women is the same (re- gardless as to whether they’ve defined their sexual orientation), it would not be consistent to explain that the reason why ho- mosexual women have certain preferences that lie between the standard preferences of heterosexual men and women is only a consequence of social influence. The authors hypothesize that exposure to prenatal androgens in homosexual women can be one of the variables responsible for the enhancement of visual stimuli and less appreciation of partner’s social status. According to this hypothesis a higher/lesser exposure or sen- sitivity to prenatal androgens (for example, the greater/smaller amount of receptors for these hormones) may be one of the variables that contribute to homosexuality (Balthazart, 2012; Brown et al., 2002; Kangassalo et al., 2011; Rice, Friberg, & Gavrilets, 2012). The exposure of the female fetus to high doses of testosterone, or their great sensitivity regarding this hormone, would influence a differential development of physical traits, especially in regions of the brain (like the suprachiasmatic nuc- leus, larger in homosexual men, when compared to heterosex- ual ones), that can also be brought back to differences in sexual behavior (Balthazart, 2012; Brown et al., 2002; Kangassalo et al., 2011; Rice, Friberg, & Gavril ets , 2012). This influence pos- sibly occurs after the forming of the sexual organs and therefor does not affect the fetus’ development (Balthazart, 2012; Brown et al., 2002; Kangassalo et al., 2011). These differences end up being irreversible (Balthazart, 2012; Brown et al., 2002; Kangassalo et al., 2011). The discrepancies in concentrations of testosterone in the uterus cannot be detected in the adult, tha t ’s why we infer their prenatal influence through measurable signs in adulthood, like the difference of the proportion of the annular and index fingers (2D:4D proportion), since the growth of these bones seem to suffer influence of prenatal steroid hormones (Balthazart, 2012; Brown et al., 2002; Kangassalo et al., 2011). Heterosexual men and women show differences in the 2D:4D proportion, bei ng that men are disproportionate in this measure, compared to women (Balthazart, 2012; Brown et al., 2002; Kangassa lo et al., 2011). Homosexual women, compared to he- terosexual women, present greater disproportionality, resem- bling men in this aspect (Hall & Love, 2003). Kenrick et al. (1995) point to the possibility that sexual pre- ference mechanisms are different between homosexuals and heterosexuals, the same way that they are different between heterosexual men and women. Despite this hypothesis, t hey did not specifically discuss the differential pattern of age preference between homosexual and heterosexual women in their research. To the authors it seems plausible that the same process that causes the modification of the sexual orientation is also respon- sible for changes in mechanisms of partner choice. The re- maining authors reviewed do not offer very clear accounts about the collected data. Our goal here is to contribute to the discussion about the si- milarities and/or differences in choosing partners for short and long term by comparing two groups: lesbians and heterosexual women. Our main hypotheses are: 1) Both homosexual and heterosexual women value more physical attractiveness in short-term relat ionships and attributes related to the formation of good bonding and providing re- sources in long-term relationships. 2) Homosexual women may have greater preference for attributes that are generally more valued by heterosexual men. Method This research has been approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee registered under the number 045/09. Parti cipa nts The data collection was accomplished with the participation of 100 Brazilian women, from the age of 18 to 40, of reproduc- tive age (meaning they were still having their periods), having at least completed secondary education and which considered their sexual orientation to be homosexual or homosexual with intermittences of heterosexuality, after the adapted Kinsey Scale (Menezes, 2005). The data of the present research was compared to the data collected in the research by Cruz (2009), using the Partner Se- lection Instrument (PSI) and applying changes relative to the gender of the chosen partner. The participants in this study V. VELOSO ET AL. OPEN ACCESS were 55 Brazilian women, heterosexuals of reproductive age, between the age of 20 and 50 and had at least completed sec- ondary education. The data from the research of Cruz (2009) was reanalyzed statistically in the present study. Instruments Sample Sel ec t ion Instrument (SSI) Based on Garc i a (2005) The instrument was composed by a brief presentation of the research project, followed by four questions, the last being of the multiple-choice type: 1) Place of Birth; 2) Age; 3) Educa- tion level; 4) Table relating fantasy and desire for person (of the same or opposite sex), sexual activity, self-classification in terms of hetero/homosexual orientation and their variations. Partner Selection Instrument (PSI), Adapted from Cruz (2009) This instrument has been tested with 600 heterosexual wo- men since 2005 and got concordance rates of over 85%. The applied adaptations were restricted to only the necessary ones for the data collection with gay women. e.g. Changing the word “partners” in the Portuguese language from the masculine form (parceiros) to the feminine form (parceiras). It came with a term of free and informed consent and was di- vided in five sections, being that in the study at hand only the following sections were used: Section 1—Demographic data about the participant. Section 2—General information about the relationship and the current/last partner. In this section questions were asked about the period of the relationship, if the participant lives or lived with their partner, their partner’s age , their income, etc. Section 3—Information about the characteristics of a poten- tial mate (not differentiating between short and long term rela- tionships). The following request was made to the participant: “Indicate with an ‘X’ how important you consider these cha- racteristics in a man/woman to get involved with this person.” The characteristics were pre-set and the participant had to give a weight (unimportant, a little important, more or less important, very important and extremely important) to the following at- tributes of the potential partner: sincere, responsible, beautiful, companion, expansive, stable, attractive, uncommitted (some- one who does not accept serious commitments), understanding, voluptuous (good sexual performance), affectionate, funny, edu- cated, independent (financially), inconstant, enamored, deter- mined, considerate. Section 4—Criteria for choosing a long-term and short-term partner. The following request was made to the participant: “Put an ‘X’ on the frequency with which you use the following criteria when selecting a fixed partner” (the same request was made for a casual partner). Under each question there was a listing of some attributes (described in section 3) in which the participant had to indicate how frequently she employed those criteria when choosing a partner (never, almost never, some- times, almost always, always). Procedure The research was conducted in the city of Belém, Pará— Brazil. The invitation to participate was done by approaching potential partakers in bars and associations where homosexual women gather. The procedure to contact the participants was: Bars and Associations Where People of Various Sexual Orientations Come Together The contact was made in two steps: a) Invitation: In bars and associations, the researchers would inform the potential participants that they were conducting a study about partner choice, and ask those interested to take part later on, to fill out the SSI and leave their contact info at the end of the form. Bar owners and those in charge of the associations, were contacted days before the collection of data. Their permission was collected in the form of a term of authorization. In the bars, the data collection would start when business is slow. The clients were approached within the first fifteen mi- nutes since they arrived at the establishment. b) Submitting the PSI: After classifying and selecting the participants that met the requirements to take part in the research, these were contacted by telephone, and during the call it was explained to them that the research consisted in submitting a questionnaire, on which they had to point out how much importance they attached to certain traits in a potential partner. Collection of Data through Approachability and Referral In this case, the contact was made by telephone with the po- tential partaker, and during the call it was explained that the research consisted in submitting a questionnaire, on which she had to point out how much importance she attached to certain traits in a potential partner. The PSI was handed over together with the SSI, with the aim to confirm that the person met the conditions required for taking part in the study. Under these circumstances the participant would not leave her contact info on the SSI. In both methods for recruiting participants, these were able to choose where they wanted to respond to the questionnaire (home, work or public places) and whether they wanted to do that in the presence of the researcher or not. Results The data will be presented using the macro-categories ob- tained by Cruz (2009) in part of his research. The characteris- tics put forward by the participants of this study gave birth to four macro-categories. The major part of the attributes corre- sponded to the macro-category Attachment Formation (com- panion, sincere, expansive, affectionate, understanding, f unny , considerate and enamored), followed by Good Provider (stable, responsible, educated, independent and determined), Good Genes (handsome, attractive and voluptuous) and Transient (uncommitted and inconstant). General Description of the Res ults a) Homosexual participants: 84% were attending college, had already graduated or held a post-graduation, 74% were em- ployed and 69.4% were absolutely or quite independent of the partner, financially speaking. Their partner’s age ranged be- tween 18 and 44 years, 71.5% were attending college, had al- ready graduated or held a post-graduation, 11.1% did not have an income. In regard to the affectionate relationship, 76% of the participants claimed to be involved in a serious relationship, 46.9% were in a relationship of 1 to 5 years, only 8% had chil-  V. VELOSO ET AL. OPEN ACCESS dren. b) Heterosexual participants: Data of 55 women of Cruz’s data collection (2009) was re-analyzed. All were properly em- ploy ed , were between 20 and 50 years old and of reproductive age. 66.7% were attending college, had already graduated or held a post-graduation, 100% were employed and were abso- lutely or largely independent of the partner, in financial terms. Their partner’s age ranged between 21 and 59 years, 61.8% were attending college, had already graduated or held a post- graduation, 6.3% did not have an income. Regarding the affec- tionate relationship, 51% said to be involved in a serious rela- tionship, 27.3% were in a relationship of 1 to 5 years, 23.6% were in a relationship of 6 months to1 year, 21.8% were in a relationship of 5 to 10 years, 56% had children. Differences between Homosexual and Heterosexual Parti cipa nts By means of descriptive statistics, using the median, a com- parison was made between the attributes in long- and short- term partnerships within both groups. The results are shown in Table 2. With the statistical test Mann-Whitney, a comparison was made between the attributes in long-term partnership within both groups, and the same in short-term. This revealed signifi- cant statistical differences: a) Long-term: among the statistically significant attributes, handsome was more important to homosexual women; respon- sible, independent, single and inconstant were more relevant to heterosexuals. Handsome was seen as “almost always” important for ho- mosexuals. Responsible and single were rated as “always” important; independent and in constant as, respectively, “al- most always” and “almost never” important among hetero- sexual women. Table 3 shows the results of the Mann-Whit - ney test . b) Short-term: Of the statistically significant attributes, at- tractive and handsome were given more importance among homosexual women, while determined, single, independent, re- sponsible and enamored were found to be more relevant among heterosexuals. In short-term, even though the attribute handsome was more relevant to homosexual women, it was classified as “almost always” important for both groups. Determined was likewise “almost always” important for both groups, despite having more relevance for heterosexuals. Table 4 describes the results of the Mann-Whitney test. Comparison between Homosexuals and Heterosexuals without Children Using the Mann-Whitney test to compare all homosexual participants with childless heterosexual participants (24 women) it was noted that in long - and short-term relationships t he attribute handsome had more weight for homosexuals (Medianhomosexuals = 40,000 and heterosexuals Medianheterosexuals = 30,000, U = 785,000, p = .00 5, r = −.61) and that in the long-term deter- mined had more weight for the heterosexuals (Medianheterosexual s = 50,000 and homosexuals Medianhomosexuals = 5,0000, U = 1,095,000, p = .001, r = −.16). Discussion In the present study, the macro-categories Attachment For- mation, Good Provider and Good Genes were , to some extent, valued by homo and heterosexual women. This given is in line with the literature (Altafim et al., 2009; Buss, 1989, 2006; Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Buss & Shakelford, 2008; Castro, 2009; Cruz, 2009; Carneiro, 1997; Greengross & Miller, 2008; Lippa, 2007; Stewart et al., 2000), as is the case of the great importance at- tached to the first two macro-categories in long-term relation- ships, and t o the las t in short -term relationships, as predicted in the first hypothesis (Buss & Shakelford, 2008; Campos, 2005; Castro, 2009; DeWaal & Maner; 2008; Lucas et al., 2011; Schmitt, 2005; Stewart et al., 2000). On the whole, characteristics related to “Good Genes” (long- term: handsome and short-term: attractive and handsome) had more weight among homosexual women, in both types of rela- tionships. It would be possible to conjecture that the inclination of homosexual women towards characteristics related to “Good Genes” is some kind of “luxury” as a result of the lack of social demand or the lesser chance at having children, compared to heterosexual women, leaving their priorities open in other di- rections, as pointed out by other researchers, like Lippa (2007). The author puts forward the hypothesis, that the high preference of women for emotional investment, at the expense of invest- ment in resources, occurs when the gender equality index is higher in their countries. It is important to stress that the studies of Kenrick et al. (1995), Russock (2011) and Bailey et al. (1994), the differences between homosexual and heterosexual women do not make direct mentioning of differences in preference for physical at- tractiveness. In search of Bailey et al. (1994), the ter m physical attractiveness is used and no difference was detected. However, there is a difference in preference for visual sexual stimuli (e.g. Table 2. Percentage of preferences between the groups in the macro-categories between short- and long-term. Macro-categories Attributes “always” and “almost always” important Long-term Short-term Homosexuals Heterosexuals Homosexuals Heterosexuals Attachment formation 53.33% 50% 50% 46.7% Good provider 26.7% 31.25% 20% 26.7% Good genes 20% 12.25% 30% 20% Transient - 6.25% - 6.7% Note: Dashes within cells indicate that these data d oesn’t exi st.  V. VELOSO ET AL. OPEN ACCESS Table 3. Statistically significant attributes in long-term relationships. Attributes U P R N Responsible 2,251,000 .038 −.46 154 Handsome 1,986,000 .007 −.6 153 Single 777,000 <.001 −1.7 151 Independent 1,948,000 .002 −.68 154 Inconstant 2,109,000 .018 −.53 153 Table 4. Statistically significant attributes in short-term relationships . Attributes U P R N Responsible 1,929,000 .002 −.68 153 Handsome 1,520,500 <.001 −1.03 152 Attractive 2,103,000 .037 −.46 150 Single 1,533,500 <.001 −.93 150 Independent 2,145,000 .030 −.48 153 Inconstant 2,142,000 .036 −.47 152 Enamored 2,144,500 .029 −.48 153 Determined 2,036,500 .007 −.6 154 pornography). The characteristics of these stimuli are not clearly defined in the study, which does not make it safe to assume that this term refers to the attractiveness. Furthermore, in Kenrick et al. (1995) and Russock (2011), the preference for younger women among homosexual women, both in general and in the course of aging, could be an indication of greater preference for attractiveness. It’s not possible to maintain that the results of the present study confirm the differences of preference for younger part- ners and for visual sexual stimuli between homosexual and heterosexual women, given that the terms employed for evalu- ating attractiveness in this study are attractive and handsome. It’s possible that these two terms are very general for evaluating this kind of attribute, and that the results would be different in case these attribute options were subdivided in subcategories, like age, for example. Furthermore, it may be that the thing which the homosexual participants evaluated as attractiveness is closely related to age. It is therefore essential that the notion of attractiveness be subdivided into more specific subcategories in subsequent studies. In any case, a priori, this research disagrees with the disclo- sures of Bailey et al. (1994) which conclude that there is no difference between women of both sexual orientations regard- ing the preference they have for the attractiveness of their part- ner, since the two groups of participants in this research pre- sented significant differences in this aspect. Moreover, this study also dissents from the research by Ha et al. (2012) which displayed different valuing of physical attractiveness of the partner, with heterosexual women giving more importance to this attribute. In the results of the studies by Bailey et al. (1994), Kenrick et al. (1995), Russock (2011) and the present study, homosexual women tend towards characteristics which were widely ob- served in researches conducted with heterosexual men (charac- teristics which have greater preference among men when com- pared to heterosexual women), as predicted in the second hy- pothesis, even though these women present less interest for these preferences, when compared to those men. Other researchers, like Balthazart (2012) and Bailey et al. (1994), have been stressing the fact that feminine preference for physical attributes may not be of a purely ecological or social nature. Bailey et al. (1994) point out the importance of the influence exerted by intrauterine testosterone on the behaviour of the individual in adult life. If some women were exposed to this influence, as is common among male fetuses, it’s possible to assume that some of their physical structures (like brain differ- ences) predispose them to behaviours that are more commonly masculine, and probably a lso determine their predisposition for certain preferences in relationships. It has been disclosed that there are differences in the 2D:4D proportionality between homo and heterosexual women (the former being more dispro- portionate), what would indicate, in last instance, that the for- mer suffered more influence of testosterone than the latter (Balthazart, 2012). Investigations are necessary at this level, aiming to throw out, reassert or round out other theoretical proposals. Confirming the studies of Bailey et al. (1994), Lippa (2007), Russock (2011) and Smith et al. (2011) the data of the present study shows that heterosexual women value traits related to good providing of resources, much more than do homosexual women. In this case, regardless of the type of relationship and income, given that the women from both groups were rather financially independent from their partners. In the studies by Bailey et al. (1994), Lippa (2007), Russock (2011) and Smith, Konik and Tuve (2011) these women valued social status and resources, and in the present study they attached more impor- tance to the attributes responsible and independent. We could justify the higher appreciation of attributes related to the macro-category Good Provider (responsible and inde- pendent) among heterosexual women, in both types of rela- tionship, by the need of providing a living for their children, since only 8% of the homosexual women have children, against 56.36% in the heterosexual participants’ camp. The fact that a big part of the heterosexual women have children, could have contributed to this valuation, for in the comparison between homosexual and heterosexual women without children this divergence did not occur. The data seems to reveal the impor- tance of the influences from the outside of the organism in the process of partner choice, as well as the malleability of its me- chanisms, as underlined by Gangestad, Haselton and Buss (2006). Meanwhile, in the same comparison above, between homo- sexual and heterosexual women without children, it was noted that the difference remained the same for the attribute hand- some, in both types of relationship (similar to the male hetero- sexual characteristic). In other words, this result may possibly not be justified by the exi stence of a child and it’s al so possible that it cannot be justified by the perspective of having a child either. The why of this difference not being very clear at the moment, it’s possible that one of the main factors contributing to it is being epigenetically influenced (Rice, Friberg, & Gavri - lets, 2012), especially through physical alterations brought about by prenatal androgenic hormones or more/less sensitivity to these, as pointed out by Bal thazart (201 2), Bail ey et al. (1994) and Rice, Friberg and Gavrilets (2012). However, researches on  V. VELOSO ET AL. OPEN ACCESS partner selection associated to these comparisons have yet to be accomplished. The authors of the present study will proceed to comparisons, associating these variables in ulterior studies. Acknowledgemen ts We thank Marilu Cruz for giving us part of her data. We thank Mauro Dias Silva Junior for his help in the general for- matting aspects of this manuscript and Giovanni Taytelbaum for his care with translating this material. We thank our friends who helped us make contact with many of participants, spe- cially Elaine Nunes, Keila Rebelo, Aline Menezes and Mauro Silva Junior. We are grateful for the support of Coordenação de Aper- feiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), through the award of PhD scholarship for the first author. We thank to the Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação from Federal University of Para (PROPESP/UFPA) and to the Fundação de Amparo e Desenvolvimento da Pesquisa (FADESP) by the fi- nancial support to the translation of this manuscript. REFERENCES Altafim, E. R. P., Lauandos, J. M., & Caramaschi, S. (2009). Seleção de parceiros: Diferenças entre gêneros em diferentes contextos. Psi- cologia e argumento, 27, 117-129. Bailey, J. M., Gaulin, S., Ag yei, Y., & Gl adue, B. A. (1 994). Effects of gender and sexual orientation on evolutionarily relevant aspects of human mating psychology. Journal of Personality and Social Psy- chology, 6, 1081-1093. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.6.1081 Balthazart, J. (2012). Sex differences suggest homosexuality is an en- docrine phenomenon. The biology of homo sexuality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Borrione, R. T. M. , & Lordel o, E. R. (200 5). Escolha de p arceiros e in - vestimento parental: Uma perspectiva desenvolvimental. Interação em Psicologia, 9, 35-43. Brown, W. M., Finn, C. J., Cooke, B. M., & Breedlove, S. M. (2002). Differences in finger length ratios between self-identified “butch” and “femme” lesbians. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31, 117-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1014091420590 Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex d iff erences in hu man mate pref erences: Ev olu- tionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sci- ences, 12, 1-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00023992 Buss, D. M. (1995 ). Psychological sex differe nces: Origins through sexual selection. American Psychologist, 50, 164-168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.50.3.164 Buss, D. M. (2006). Strategies of human mating. Psychological Topics, 15, 239-260. Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100, 204-232. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.2.204 Buss, D. M., & Shakelford , T. K. (2008). Attractive women want it all: Good genes, economic investment, parenting proclivities, and emo- tional commitment. Evolutionary Psychology, 6, 134-146. Campos, L. S. (2005). Relacionamentos amorosos de curta e longa duração: Uma análise a partir de anúncios classificados (Doctoral dissertation). http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/47/47132/tde-16082013-14 3506/pt-br.php Carneiro, T. F. (199 7). Escolh a a moros a e inte ração conjugal relação na heterossexualidade e na homossexualidade. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 10, 351-368. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79721997000200012 Castro, F. N. (2009). Preferências e escolhas românticas entre uni- versitários (Marters’s thesis). http://www.dominiopublico.gov.br/pesquisa/DetalheObraForm.do?se lect_action=&co_obra=139117 Corrêa, H. V. V. (2011). Critérios utilizados na seleção de parceiras amorosas em relaciona mentos de curto e lon go prazo entre mulheres de orientação homossexual em idade reprodutiva (Marters’s thesis). http://www.ufpa.br/ppgtpc/dmdocuments/MESTRADO/DissertHelle nCorrea2011.pdf Covolan, N. T. (2005). Corpo vivido e gênero: A menopausa no ho- moerotismo feminino (Doctoral dissertation). https://periodicos.ufsc.br/index.php/cadernosdepesquisa/thesis/view/272 Cruz, M. M. S. (2009). Relações de fertilidade feminina com a escolha de parceiros. Masther’s Thesis, Pará: Universidade Federal do Pará. DeWaal, C. N., & Maner, J . K. (2008). High status men (but n ot wom- en) capture the eye of the beholder. Evolutionary Psychology, 6, 328-341. Fiore, T. A., Taylor, L. S., Zhong, X., Mend elsohn, G. A., & Cheshire, C. (2010). Who’s right and who writes: People, profiles, contacts, and replies in online dating (pp. 1-10). IEEE Xexplore-Digital Li- brary. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2010.444 http://www.computer.org/csdl/proceedings/hicss/2010/3869/00/03-0 6-05-abs.html Fisher, H. (1995). Anatomia do amor: A históri a natural da monogamia, do adultério e do divórcio. Rio de Janeiro: Eureka. Furnham, A. (2009). Sex differences in mate selection preferences. Per- sonality and Individual Differences, 47, 262-267. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.03.013 Gangestad, S . W., Haselton, M. G., & Buss, D. M. (2006) . Evolutionary foundations of cultural variation: Evoked culture and mate prefer- ences. Psychological Inquiry, 17, 75-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1702_1 Gangestad, S. W., & Simpson, J. A. (2000). The evolution of human mate: Trades-off and strategic pluralism. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23, 573-644. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0000337X Gárcia, A. P. (2005). Relatos de homo e heterossexuais femininos acerca do comportamento de cuidar de parentes. Unpublished Mas- ter’s Thesis, Pará: Universidade Federal do Pará. Greengross, G., & Miller, G. F. (2008). Dissing oneself versus dissing rivals: Effects of s tatus, personality, and s ex on short-term and long- term attractiveness of self-deprecating and other-deprecating humor. Evolutionary Psychology, 6, 393-408. Ha, T., van den Berg, J. E. M., Engels, R. C. M., & Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A. (2012). Eff ects of attractiveness and status in dating desire in ho- mosexual and heterosexual men and women. Archives of Sexual Be- havior, 41, 673-682. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10508-011-9855-9 Hall, L. S., & Lo ve, C. T. (20 03). Finger-len gth ratios in female mono- zygotic twins discordant for sexual orientation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 23-28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1021837211630 Hattori, W. T. (2009). Projeto EPA: Escolha de parceiros na adoles- cência (Doctoral dissertation). http://ftp.ufrn.br/pub/biblioteca/ext/bdtd/WallisenTH.pdf Kangassalo, K., Pölkki, M., & Rantala, M. J. (2011). Prenatal Influ- ences on sexual or ientation: Digit ratio (2D:4D) and number of older siblings. Evolutionary Psychology, 9, 496-508. Kenrick, D. T., Keef e, R. C., Bryan, A., Barr, A., & B rown, S. (1995 ). Age preferences and mate choice among homosexuals and hetero- sexuals: A case for modular psychological mechanisms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 1166-1172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.6.1166 Lippa, R. A. (2007). The preferred traits of mates in a cross-national study of heteorsexual and homosexual men and women. An exami- nation of biological and cultural influences. Archives of Sexual Be- havior, 36, 193-208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9151-2 Lucas, M., Koff, E., Grossmith, S., & Migliorini, R. (2011). Sexual orientation and shifts in p references for a partner’s bod y attributes in short-term versus long-term mating con texts. Psychological Reports, 108, 699-710. Oliva, A. D ., Ot ta, E., Buss ab , V. S. R., Lo p es , F. A., Yama moto, M. E., & Moura, M. L . S. (2006). Razão, e moção e ação em cena: A mente humana sob um olhar evolucionista. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa,  V. VELOSO ET AL. OPEN ACCESS 22, 53-65. Pawlowski, B. (2000). The biological meaning of preferences on the human mate market. Przegląd antropologiczny. Anthropological Re- view, 63, 39-72. Rice, W. R., Friberg, U., & Gavrilets, S. (2012). Homosexuality as a consequence of epigenetically canalized sexual development. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 87, 343-368. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/668167 Russock, H. I. (2011). An evolutionary interpretation of the effect of gender and sexual orientation on human mate selection preferences, as indicated by an analysis of personal advertisements. Behaviour, 148, 307-323. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/000579511X556600 Sadala, K. Y. (2005). Estudo dos critérios de eleição de parceria amorosa em mulheres de 40 a 60 anos de idade. Unpublished Mas- ter’s Thesis, Pará: Universidade Federal do Pará. Schmitt, D. P. (200 6). Fundamentals of human mating s trategies. In D. Buss (Ed.), Handbook of evolutionary psychology (pp. 258-291). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Smith, C., Konik, J. A., & Tuve, M. V. (2011). In search of looks, status, or something else? Partner preferences among butch and femme lesbians and heterosexual men and women. Sex Roles, 64, 658-668. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9861-8 Stewart, S., Stinnett, H., & Rosenfelt, L. B. (2000). Sex differences in desired characteristics of short-term and long-term relationship part- ners. Journal of Social and Personal Re lat ionshi ps, 17, 843-853. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0265407500176008 Stone, E. A., Shakelford, T. K., & B uss, D. M. (2008). So cioeconomic development and shifts in mate preferences. Evolutionary Psycholo- gy, 6, 447-455. Wood, W., & Eagly, A. H. (2007). Social structural o rigins of sex dif- ferences in human mating. In S. W. Gangestad, & J. A. Simpson (Eds.), The evolution of mind: Fundamental questions and contro- versies (pp. 383-390). New York, London: The Guilford Press.

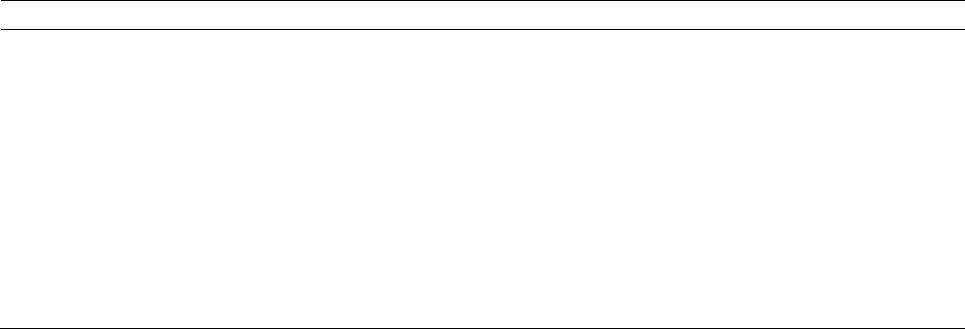

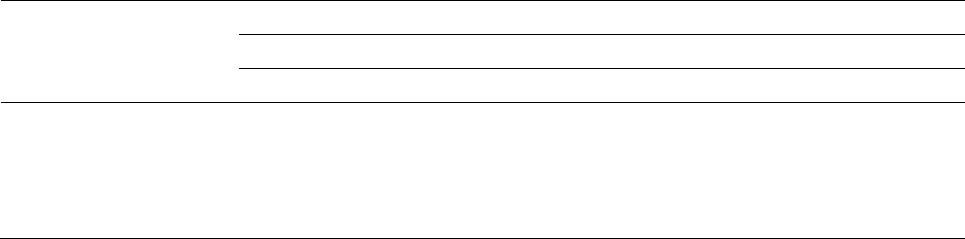

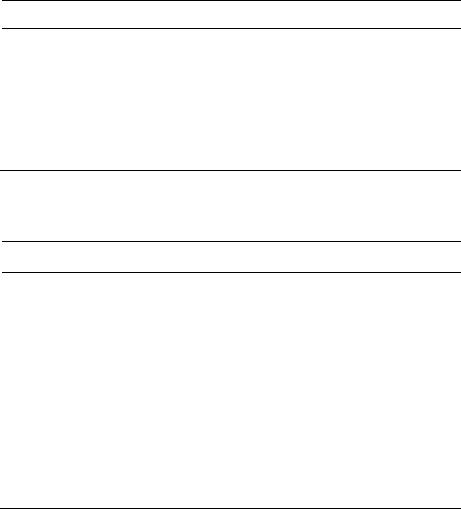

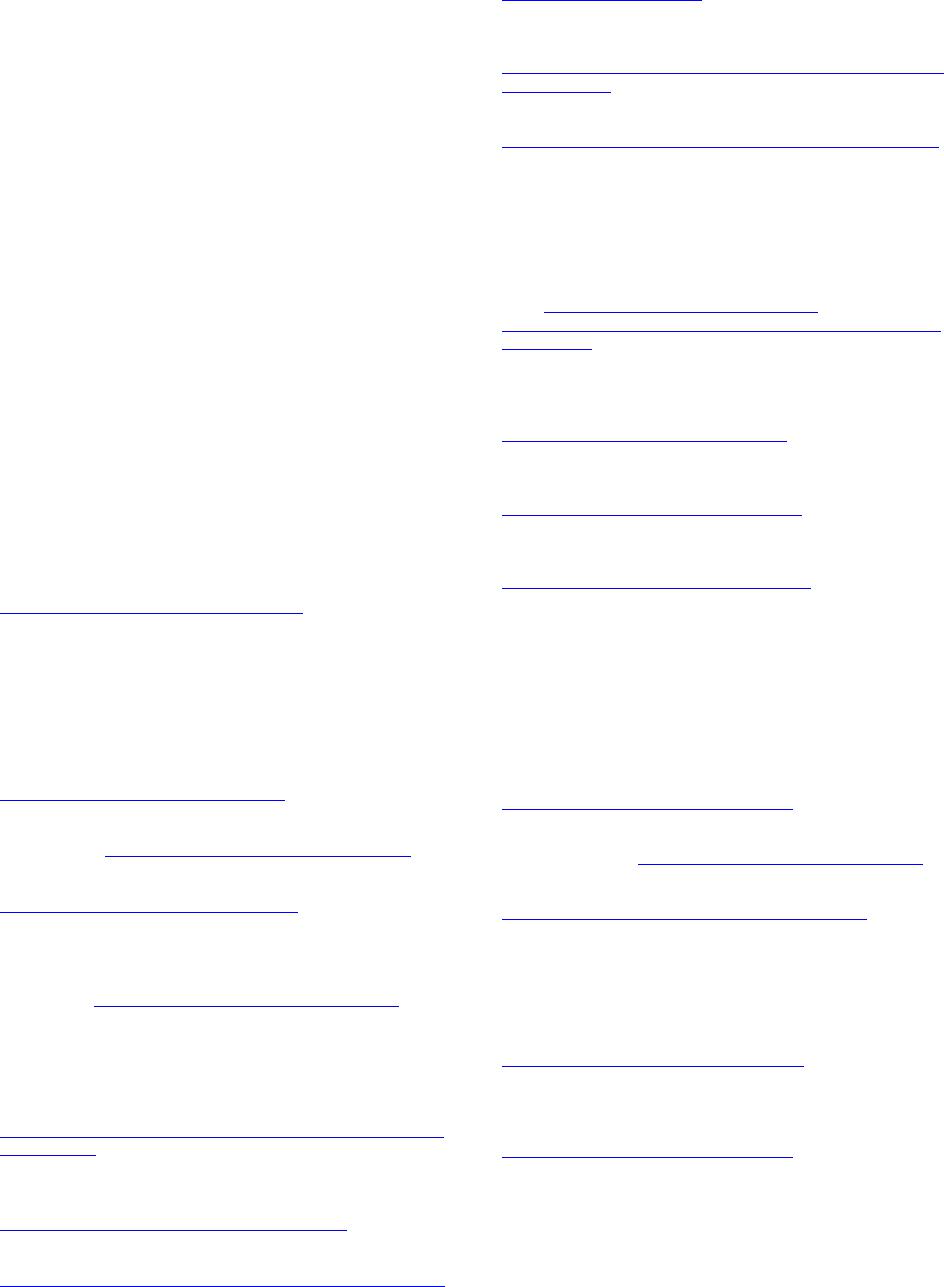

|