Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

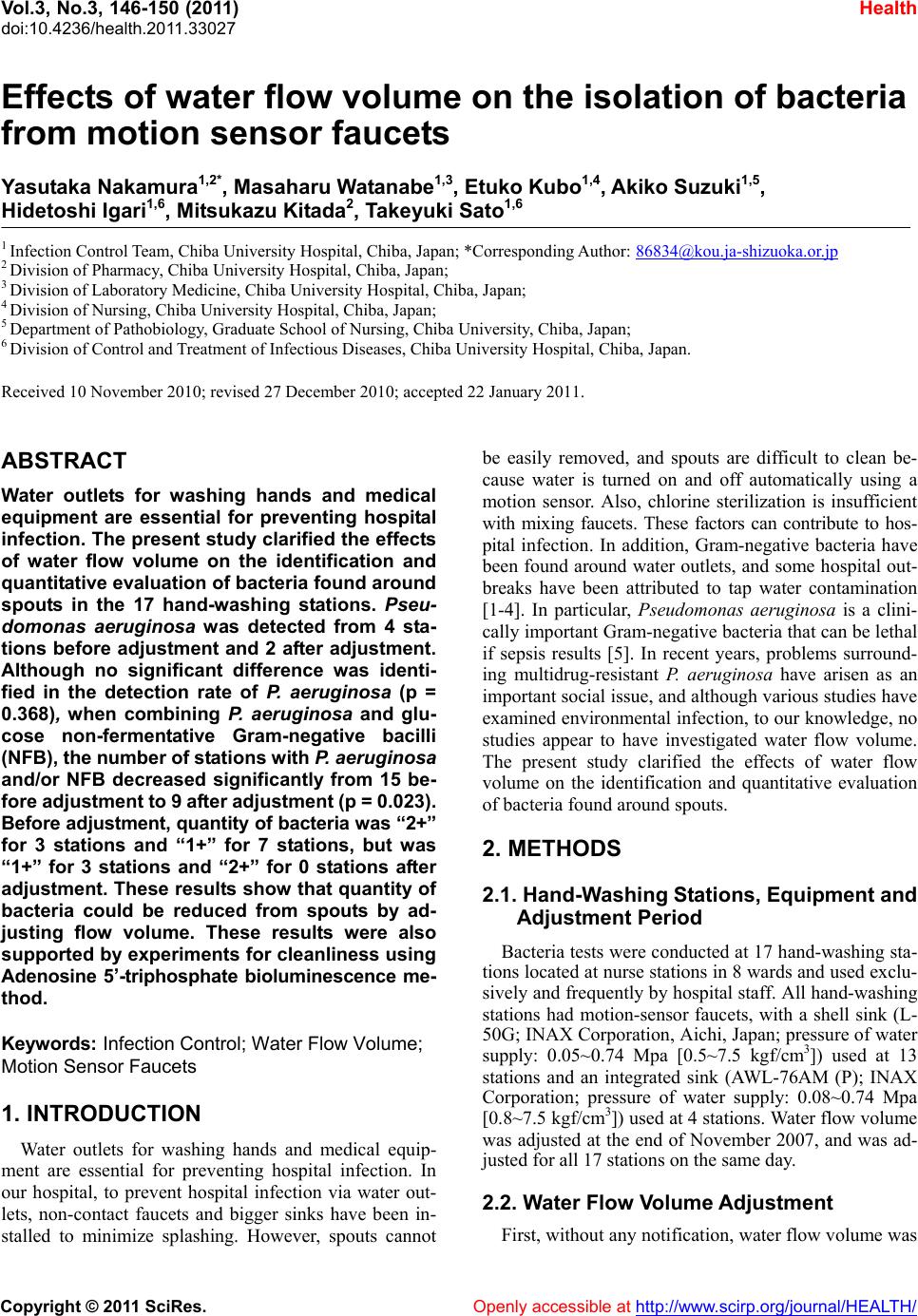

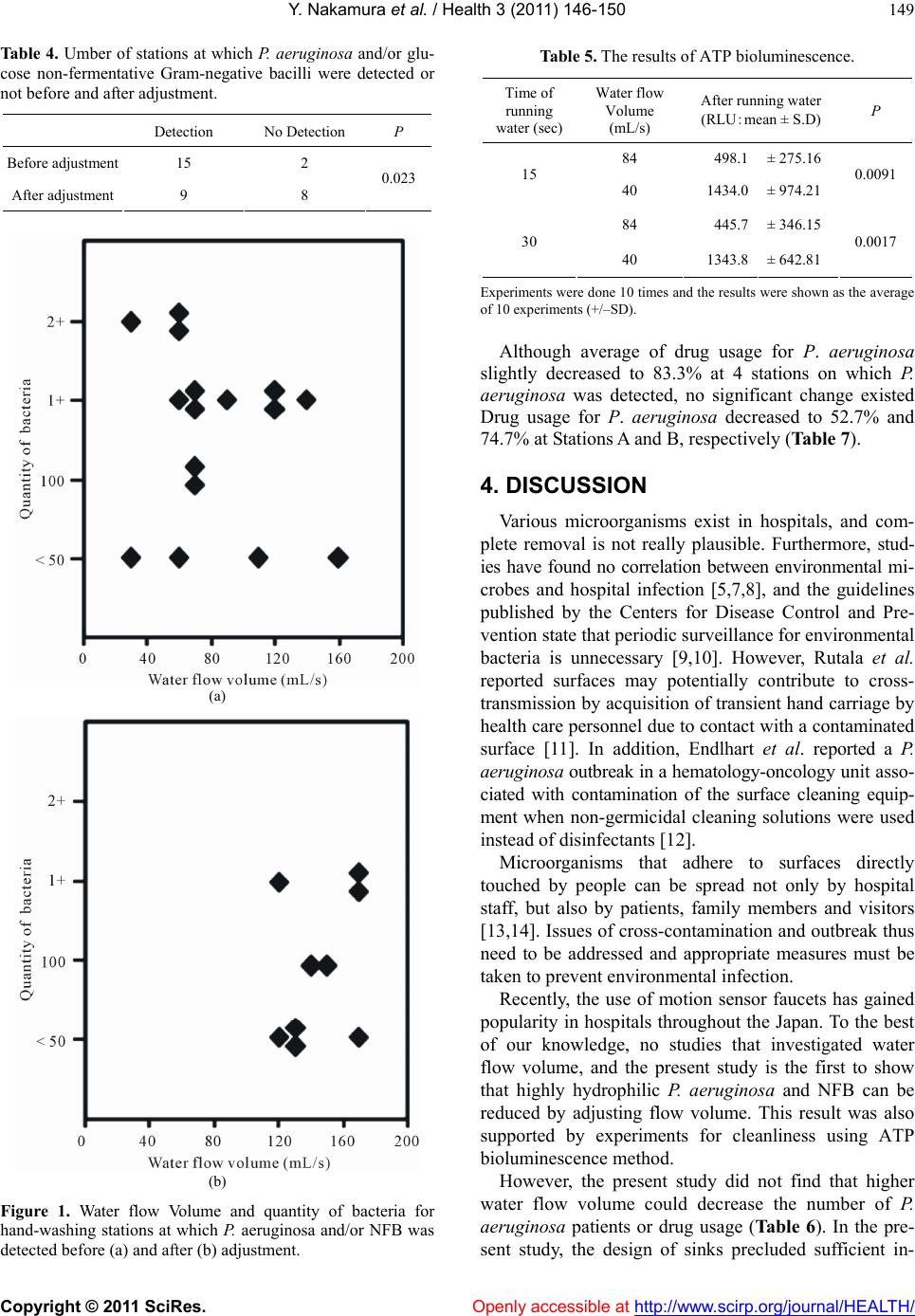

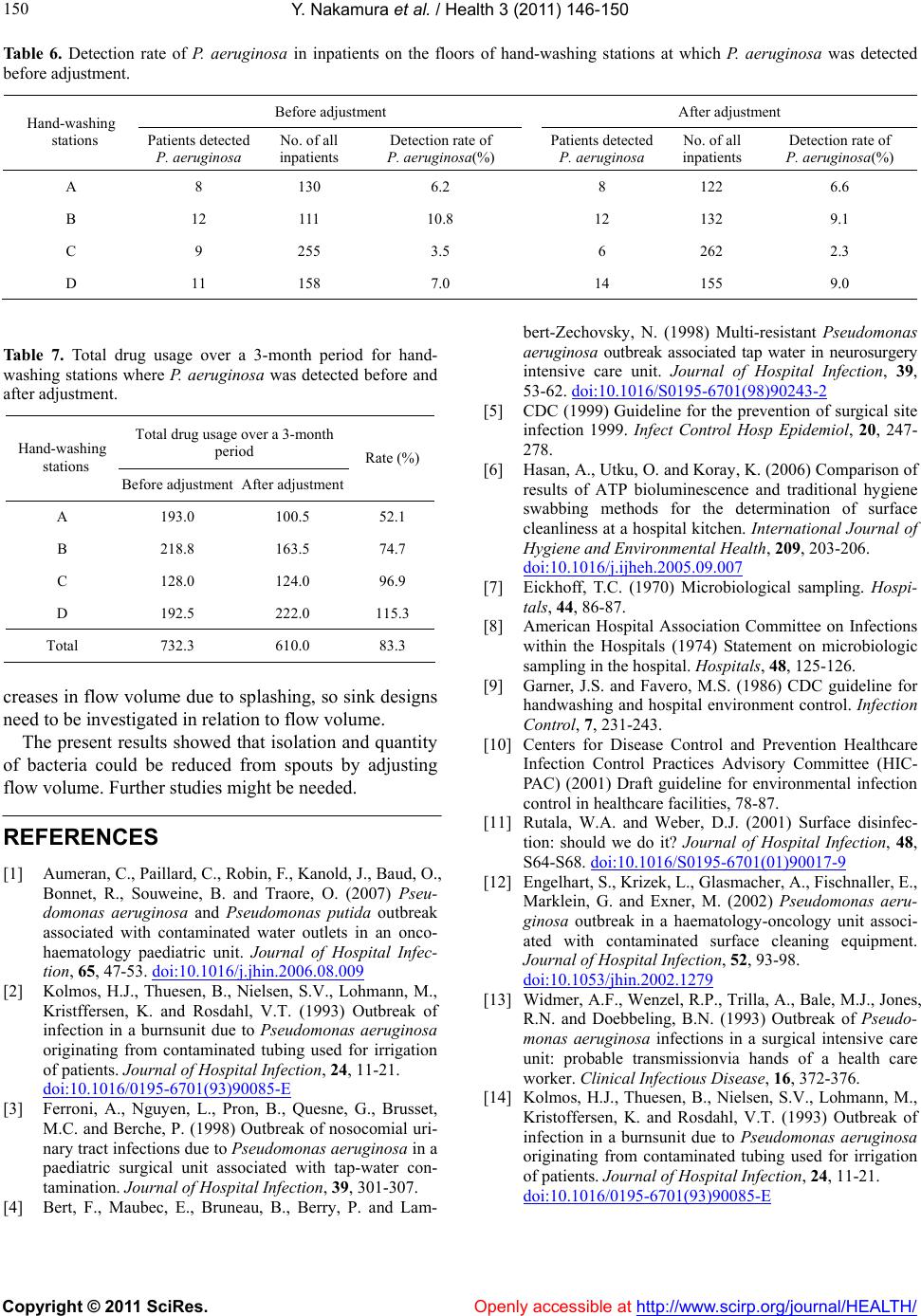

Vol.3, No.3, 146-150 (2011) Health doi:10.4236/health.2011.33027 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Effects of water flow volume on the isolation of bacteria from motion sensor faucets Yasutaka Nakamura1,2*, Masaharu Watanabe1,3, Etuko Kubo1,4, Akiko Suzuki1,5, Hidetoshi Igari1,6, Mitsukazu Kitada2, Takeyuki Sato1,6 1 Infection Control Team, Chiba University Hospital, Chiba, Japan; *Corresponding Author: 86834@kou.ja-shizuoka.or.jp 2 Division of Pharmacy, Chiba University Hospital, Chiba, Japan; 3 Division of Laboratory Medicine, Chiba University Hospital, Chiba, Japan; 4 Division of Nursing, Chiba University Hospital, Chiba, Japan; 5 Department of Pathobiology, Graduate School of Nursing, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan; 6 Division of Control and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, Chiba University Hospital, Chiba, Japan. Received 10 November 2010; revised 27 December 2010; accepted 22 January 2011. ABSTRACT Water outlets for washing hands and medical equipment are essential for preventing hospital infection. The present study clarified the effects of water flow volume on the identification and quantitative evaluation of bacteria found around spouts in the 17 hand-washing stations. Pseu- domonas aeruginosa was detected from 4 sta- tions before adjustment and 2 after adjustment. Although no significant difference was identi- fied in the detection rate of P. aeruginosa (p = 0.368), when combining P. aeruginosa and glu- cose non-fermentative Gram-negative bacilli (NFB), the number of stations with P. aeruginosa and/or NFB decreased significantly from 15 be- fore adjustment to 9 af ter adjustment (p = 0.023). Before adjustment, quantit y of bacteria w as “2+” for 3 stations and “1+” for 7 stations, but was “1+” for 3 stations and “2+” for 0 stations after adjustment. These results show that quantity of bacteria could be reduced from spouts by ad- justing flow volume. These results were also supported by experiments for cleanliness using Adenosine 5’-triphosphate bioluminescence me- thod. Keywords: Infection Control; Water Flow Volume; Motion Sensor Faucets 1. INTRODUCTION Water outlets for washing hands and medical equip- ment are essential for preventing hospital infection. In our hospital, to prevent hospital infection via water out- lets, non-contact faucets and bigger sinks have been in- stalled to minimize splashing. However, spouts cannot be easily removed, and spouts are difficult to clean be- cause water is turned on and off automatically using a motion sensor. Also, chlorine sterilization is insufficient with mixing faucets. These factors can contribute to hos- pital infection. In addition, Gram-negative bacteria have been found around water outlets, and some hospital out- breaks have been attributed to tap water contamination [1-4]. In particular, Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a clini- cally important Gram-negative bacteria that can be lethal if sepsis results [5]. In recent years, problems surround- ing multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa have arisen as an important social issue, and although various studies have examined environmental infection, to our knowledge, no studies appear to have investigated water flow volume. The present study clarified the effects of water flow volume on the identification and quantitative evaluation of bacteria found around spouts. 2. METHODS 2.1. Hand-Washing St ati ons, Equipment and Adjustment Period Bacteria tests were conducted at 17 hand-washing sta- tions located at nurse stations in 8 wards and used exclu- sively and frequently by hospital staff. All hand-washing stations had motion-sensor faucets, with a shell sink (L- 50G; INAX Corporation, Aichi, Japan; pressure of water supply: 0.05~0.74 Mpa [0.5~7.5 kgf/cm3]) used at 13 stations and an integrated sink (AWL-76AM (P); INAX Corporation; pressure of water supply: 0.08~0.74 Mpa [0.8~7.5 kgf/cm3]) used at 4 stations. Water flow volume was adjusted at the end of November 2007, and was ad- justed for all 17 stations on the same day. 2.2. Water Flow Volume Adjustment First, without any notification, water flow volume was  Y. Nakamura et al. / Health 3 (2011) 146-150 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 147 measured at each hand-washing station (pre-adjustment flow volume). Next, based on sink size, flow volume was adjusted at 120-200 mL/s (post-adjustment flow volume). Flow volume per second was calculated by measuring flow volume over a 10-s period twice. Also, when adjusting flow volume, each floor was notified that water flow volume would be adjusted as part of activi- ties of Infection Control Team (ICT) and was instructed to refrain from performing any action that could have impacted the surveillance, such as changing flow volume or contacting a cleaning service. 2.3. Sample Collection, Identification and Quantity of Bacteria Samples were collected by wiping the entire spout using a cotton swab soaked in physiological saline be- fore and after adjustment at intervals of 1 month. One person collected all samples from all hand-washing sta- tions before and after volume adjustment. Each sample was inoculated using Drigalski improved medium (Eiken Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) and tryptic soy agar II sup- plemented with 5% sheep blood (Becton Dickinson, To- kyo, Japan) and cultured at 35˚C for 72 h. Gram-positive bacilli (GPB) were identified by Gram staining alone, and Gram-positive cocci were biochemically divided into Streptococcus, Staphylococcus aureus and coagu- lase-negative staphylococci (CNS). Gram-negative ba- cilli were biochemically divided into Enterobacteriaceae, P. aeruginosa and glucose non-fermentative Gram-nega- tive bacilli (NFB). Growth was semiquantitated as follows: <50 colonies, <50 colonies in the first inoculation zone; 100 colonies, 50-100 colonies in the first zone; 1+, >100 colonies in the first zone; 2+, >10 colonies in the second zone. 2.4. Adenosine 5’-Triphosphate ( ATP ) Bioluminescence Method ATP was purchased from Oriental Yeast Co., LTD. Japan. The ATP solution at the concentration of 2.0 × 10-6 M with 1% of the starch was prepared for the ex- periments. The entire spout was cleaned by brushing with soap and water. One mL of ATP solution was poured to the faucet from the side of up-stream after removal of the faucet. After reset of forcet, water was running at various water volume for 15 and 30 seconds, respec- tively. Water flow Volume performed 40, 80 mL/ss. Then, samples were collected by wiping the entire surface of spout with the attached tape for the experiments. The experiments were done 10 times and the results were shown as the average (+/–SD). Samples were measured in relative light units (RLU) by using a luminometer (ATP Luminometer PD-20 Kikkoman Co., Japan) 2.5. Statistical Assessment When statistically analyzing bacteria detection rates in relation to flow volume adjustment, a χ2 independence test was used with the level of significance set at p < 0.05. 2.6. Detection Rate of P. Aeruginosa in Inpatients and Drug Usage for P. Aeruginosa Detection rate of P. aeruginosa in inpatients was cal- culated before and after adjustment for the entire hospi- tal and each floor at which P. aeruginosa was detected a 3-month period before and after adjustment. Drug usages for P. aeruginosa were also studied for the entire hospital and each floor at which P. aeruginosa was detected a 3-month period before and after adjust- ment. Usage of the following antibiotics injected for treatment was determined: Ceftazidime, cefepime dihy- drochloride hydrate, cefozopran hydrochloride, imipenem hydrate, meropenem hydrate, panipenem, doripenem hydrate, biapenem, pazufloxacin mesilate, and cipro- floxacin. When comparing usage among drugs, defined daily dose (DDD) as recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) was used to correct for non-uni- formity in specifications and dose (Ta b le 1) (www.wh- occ.no/atcddd/). DDD for drugs not listed by WHO was defined by modifying with the recommendation of WHO. The study period before adjustment was from August to October 2007 and after adjustment from January to March 2008. 3. Results 3.1. Water Flow Volume Before and After Adjustment Average flow volume before and after adjustment was 87.6 mL/s and 149.4 mL/s, respectively (Table 2). Before Table 1. Drug list and defined daily dose (DDD). Drugs DDD (g) Ceftazidime 4 Cefepime Dihydrochloride Hydrate 2 Cefozopran Hydrochloride 2 * Imipenem Hydrate 2 Meropenem Hydrate 2 Panipenem 2 * Doripenem Hydrate 1 * Biapenem 1.2 * Pazufloxacin mesilate 1 Ciprofloxacin 0.5 *DDD for drugs not listed by WHO was defined by modifying with the definition of WHO.  Y. Nakamura et al. / Health 3 (2011) 146-150 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 148 Table 2. Water flow Volume before and after adjustment. Water flow Volume (mL/s) 30 50 60 70 90110120130140150160170200 mean ± S.D Before adjustment 1 1 4 4 1 2 2 1 1 85.3 ± 35.4 After adjustment 4 3 2 1 1 4 2 149.4 ± 27.0 adjustment, minimum flow volume was 30 mL/s, and flow volume at 11 hand-washing stations was <120 mL/s. Maximum flow volume after adjustment was 200 mL/s. 3.2. Detection of P. Aeruginosa and NFB from Hand-Washing Stations P. aeruginosa was detected from 4 hand-washing sta- tions (A-D) before adjustment and 1 station (A) after adjustment. Quantity of bacteria was “1+” for Station A, “100 colonies” for Station D, and “<50 colonies” for Stations B and C before adjustment. After adjustment, P. aeruginosa was not detected from Stations B, C and D. P. aeruginosa was detected from Station A, but quantity of bacteria decreased from “1+” before adjustment to “<50 colonies” after adjustment. Also, at 1 station (E), P. aeruginosa was not detected before adjustment, but was detected after adjustment, although quantity of bacteria was low at “<50 colonies” (Table 3). Although no significant change was identified in the detection rate of P. aeruginosa including newly isolated 1 station (p = 0.368), when combining P. aeruginosa and NFB, the number of stations with P. aeruginosa and/or NFB decreased significantly from 15 before adjustment to 9 after adjustment (p = 0.023) (Ta b l e 4 ). Before ad- justment, quantity of bacteria was “2+” for 3 stations and “1+” for 7 stations, but was “1+” for 3 stations and “2+” for no stations after adjustment (Figure 1). As for the other bacterial species, GPB was detected before and after adjustment at 12 and 8 stations, respectively, and CNS was detected before and after adjustment at 1 sta- tion each. Streptococcus species, S. aureus and Entero- bacteriaceae were not detected. 3.3. ATP Bioluminescence ATP method is recommended due to ATP being widely found in microorganisms and there are good correlations between ATP bioluminescence method and microbi- ological swabbing method [6]. So cleanliness was ex- amined using ATP bioluminescence method for the con- firmation of microbiological swabbing method. Increase of flow volume resulted the increase of cleanliness at both 15 and 30 seconds of running water (Table 5). 3.4. Comparison of P. Aeruginosa Detection and Drug Usage among Inpatients Detection rate of P. aeruginosa in all inpatients was compared before and after adjustment. Detection rate of P. aeruginosa for all floors before adjustment was 4.5% (patients with P. aeruginosa/total patient count = 159/ 3,500) and that 3 months after adjustment was 3.6% (128/3,523). On the floors with Stations A through D where P. aeruginosa was detected before adjustment, detection rate before adjustment ranged from 3.5% to 10.8% and that after adjustment ranged from 2.3% to 9.1%, revealing no significant differences (Table 6). Total drug usage over the 3-month period for all floors before adjustment was 3,917 units and that after adjust- ment was mostly comparable at 4,083 units (102.8%). Table 3. Water flow Volume and quantity of bacteria of hand-washing stations at which P. aeruginosa were detected. Before adjustment After adjustment Hand-washing stations Type of sink Quantity of bacteria Water flow Volume (mL/s) Quantity of bacteria Water flow Volume (mL/s) A Shell 1+ 90 <50 colonies 120 B Shell <50 colonies 110 No Detection 140 C Integrated <50 colonies 30 No Detection 200 D Shell 100 colonies 70 No Detection 130 E Shell No Detection 120 <50 colonies 170  Y. Nakamura et al. / Health 3 (2011) 146-150 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 149 Table 4. Umber of stations at which P. aeruginosa and/or glu- cose non-fermentative Gram-negative bacilli were detected or not before and after adjustment. Detection No Detection P Before adjustment 15 2 After adjustment 9 8 0.023 (a) (b) Figure 1. Water flow Volume and quantity of bacteria for hand-washing stations at which P. aeruginosa and/or NFB was detected before (a) and after (b) adjustment. Table 5. The results of ATP bioluminescence. Time of running water (sec) Water flow Volume (mL/s) After running water (RLU:mean ± S.D) P 84 498.1 ± 275.16 15 40 1434.0 ± 974.21 0.0091 84 445.7 ± 346.15 30 40 1343.8 ± 642.81 0.0017 Experiments were done 10 times and the results were shown as the average of 10 experiments (+/–SD). Although average of drug usage for P. aeruginosa slightly decreased to 83.3% at 4 stations on which P. aeruginosa was detected, no significant change existed Drug usage for P. aeruginosa decreased to 52.7% and 74.7% at Stations A and B, respectively (Table 7). 4. DISCUSSION Various microorganisms exist in hospitals, and com- plete removal is not really plausible. Furthermore, stud- ies have found no correlation between environmental mi- crobes and hospital infection [5,7,8], and the guidelines published by the Centers for Disease Control and Pre- vention state that periodic surveillance for environmental bacteria is unnecessary [9,10]. However, Rutala et al. reported surfaces may potentially contribute to cross- transmission by acquisition of transient hand carriage by health care personnel due to contact with a contaminated surface [11]. In addition, Endlhart et al. reported a P. aeruginosa outbreak in a hematology-oncology unit asso- ciated with contamination of the surface cleaning equip- ment when non-germicidal cleaning solutions were used instead of disinfectants [12]. Microorganisms that adhere to surfaces directly touched by people can be spread not only by hospital staff, but also by patients, family members and visitors [13,14]. Issues of cross-contamination and outbreak thus need to be addressed and appropriate measures must be taken to prevent environmental infection. Recently, the use of motion sensor faucets has gained popularity in hospitals throughout the Japan. To the best of our knowledge, no studies that investigated water flow volume, and the present study is the first to show that highly hydrophilic P. aeruginosa and NFB can be reduced by adjusting flow volume. This result was also supported by experiments for cleanliness using ATP bioluminescence method. However, the present study did not find that higher water flow volume could decrease the number of P. aeruginosa patients or drug usage (Ta ble 6 ). In the pre- sent study, the design of sinks precluded sufficient in-  Y. Nakamura et al. / Health 3 (2011) 146-150 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 150 Table 6. Detection rate of P. aeruginosa in inpatients on the floors of hand-washing stations at which P. aeruginosa was detected before adjustment. Before adjustment After adjustment Hand-washing stations Patients detected P. aeruginosa No. of all inpatients Detection rate of P. aeruginosa(%) Patients detected P. aeruginosa No. of all inpatients Detection rate of P. aeruginosa(%) A 8 130 6.2 8 122 6.6 B 12 111 10.8 12 132 9.1 C 9 255 3.5 6 262 2.3 D 11 158 7.0 14 155 9.0 Table 7. Total drug usage over a 3-month period for hand- washing stations where P. aeruginosa was detected before and after adjustment. Total drug usage over a 3-month period Hand-washing stations Before adjustmentAfter adjustment Rate (%) A 193.0 100.5 52.1 B 218.8 163.5 74.7 C 128.0 124.0 96.9 D 192.5 222.0 115.3 Total 732.3 610.0 83.3 creases in flow volume due to splashing, so sink designs need to be investigated in relation to flow volume. The present results showed that isolation and quantity of bacteria could be reduced from spouts by adjusting flow volume. Further studies might be needed. REFERENCES [1] Aumeran, C., Paillard, C., Robin, F., Kanold, J., Baud, O., Bonnet, R., Souweine, B. and Traore, O. (2007) Pseu- domonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas putida outbreak associated with contaminated water outlets in an onco- haematology paediatric unit. Journal of Hospital Infec- tion, 65, 47-53. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2006.08.009 [2] Kolmos, H.J., Thuesen, B., Nielsen, S.V., Lohmann, M., Kristffersen, K. and Rosdahl, V.T. (1993) Outbreak of infection in a burnsunit due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa originating from contaminated tubing used for irrigation of patients. Journal of Hospital Infection, 24, 11-21. doi:10.1016/0195-6701(93)90085-E [3] Ferroni, A., Nguyen, L., Pron, B., Quesne, G., Brusset, M.C. and Berche, P. (1998) Outbreak of nosocomial uri- nary tract infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a paediatric surgical unit associated with tap-water con- tamination. Journal of Hospital Infection, 39, 301-307. [4] Bert, F., Maubec, E., Bruneau, B., Berry, P. and Lam- bert-Zechovsky, N. (1998) Multi-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa outbreak associated tap water in neurosurgery intensive care unit. Journal of Hospital Infection, 39, 53-62. doi:10.1016/S0195-6701(98)90243-2 [5] CDC (1999) Guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection 1999. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 20, 247- 278. [6] Hasan, A., Utku, O. and Koray, K. (2006) Comparison of results of ATP bioluminescence and traditional hygiene swabbing methods for the determination of surface cleanliness at a hospital kitchen. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 209, 203-206. doi:10.1016/j.ijheh.2005.09.007 [7] Eickhoff, T.C. (1970) Microbiological sampling. Hospi- tals, 44, 86-87. [8] American Hospital Association Committee on Infections within the Hospitals (1974) Statement on microbiologic sampling in the hospital. Hospitals, 48, 125-126. [9] Garner, J.S. and Favero, M.S. (1986) CDC guideline for handwashing and hospital environment control. Infection Control, 7, 231-243. [10] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HIC- PAC) (2001) Draft guideline for environmental infection control in healthcare facilities, 78-87. [11] Rutala, W.A. and Weber, D.J. (2001) Surface disinfec- tion: should we do it? Journal of Hospital Infection, 48, S64-S68. doi:10.1016/S0195-6701(01)90017-9 [12] Engelhart, S., Krizek, L., Glasmacher, A., Fischnaller, E., Marklein, G. and Exner, M. (2002) Pseudomonas aeru- ginosa outbreak in a haematology-oncology unit associ- ated with contaminated surface cleaning equipment. Journal of Hospital Infection, 52, 93-98. doi:10.1053/jhin.2002.1279 [13] Widmer, A.F., Wenzel, R.P., Trilla, A., Bale, M.J., Jones, R.N. and Doebbeling, B.N. (1993) Outbreak of Pseudo- monas aeruginosa infections in a surgical intensive care unit: probable transmissionvia hands of a health care worker. Clinical Infectious Disease, 16, 372-376. [14] Kolmos, H.J., Thuesen, B., Nielsen, S.V., Lohmann, M., Kristoffersen, K. and Rosdahl, V.T. (1993) Outbreak of infection in a burnsunit due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa originating from contaminated tubing used for irrigation of patients. Journal of Hospital Infection, 24, 11-21. doi:10.1016/0195-6701(93)90085-E |