Paper Menu >>

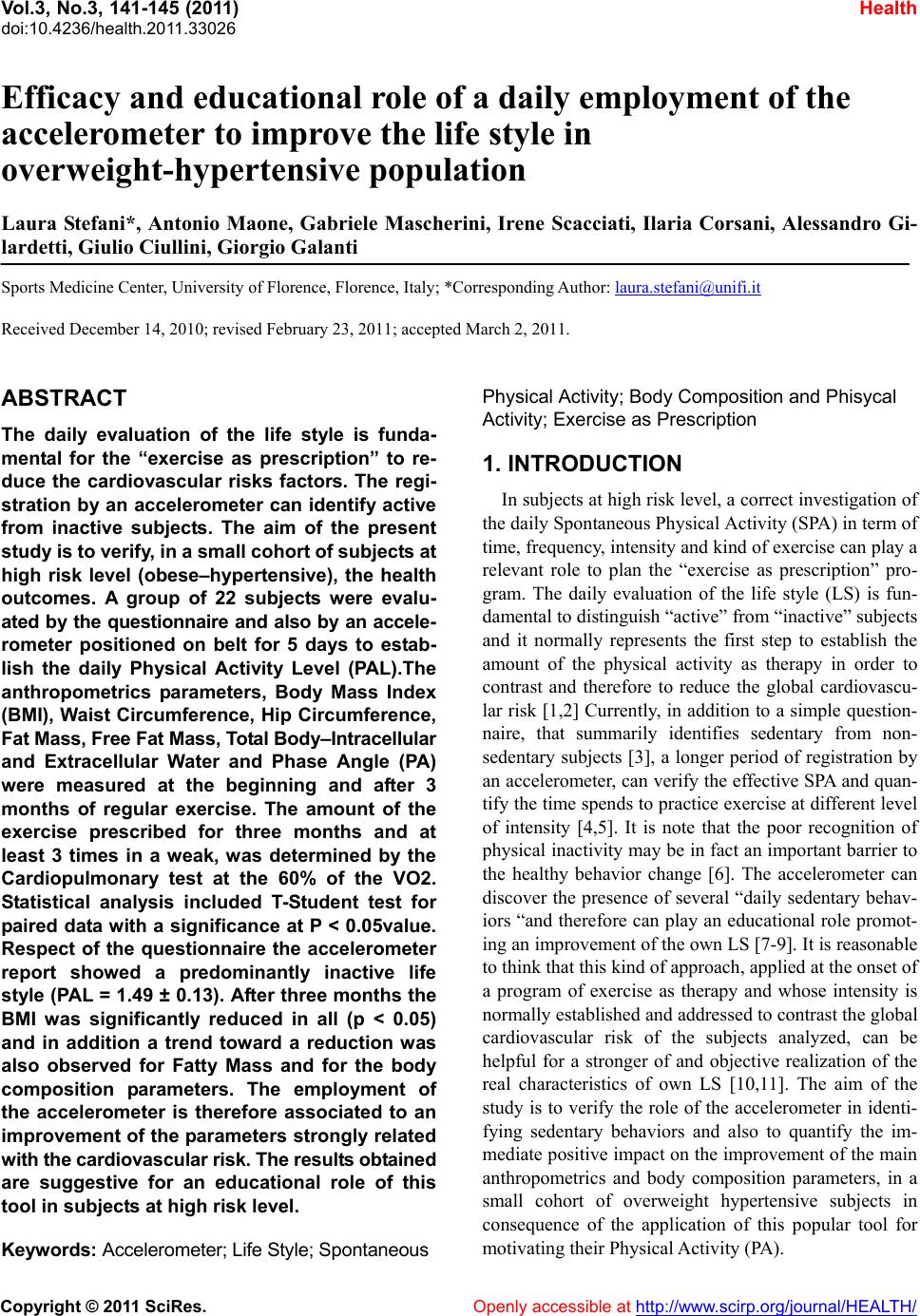

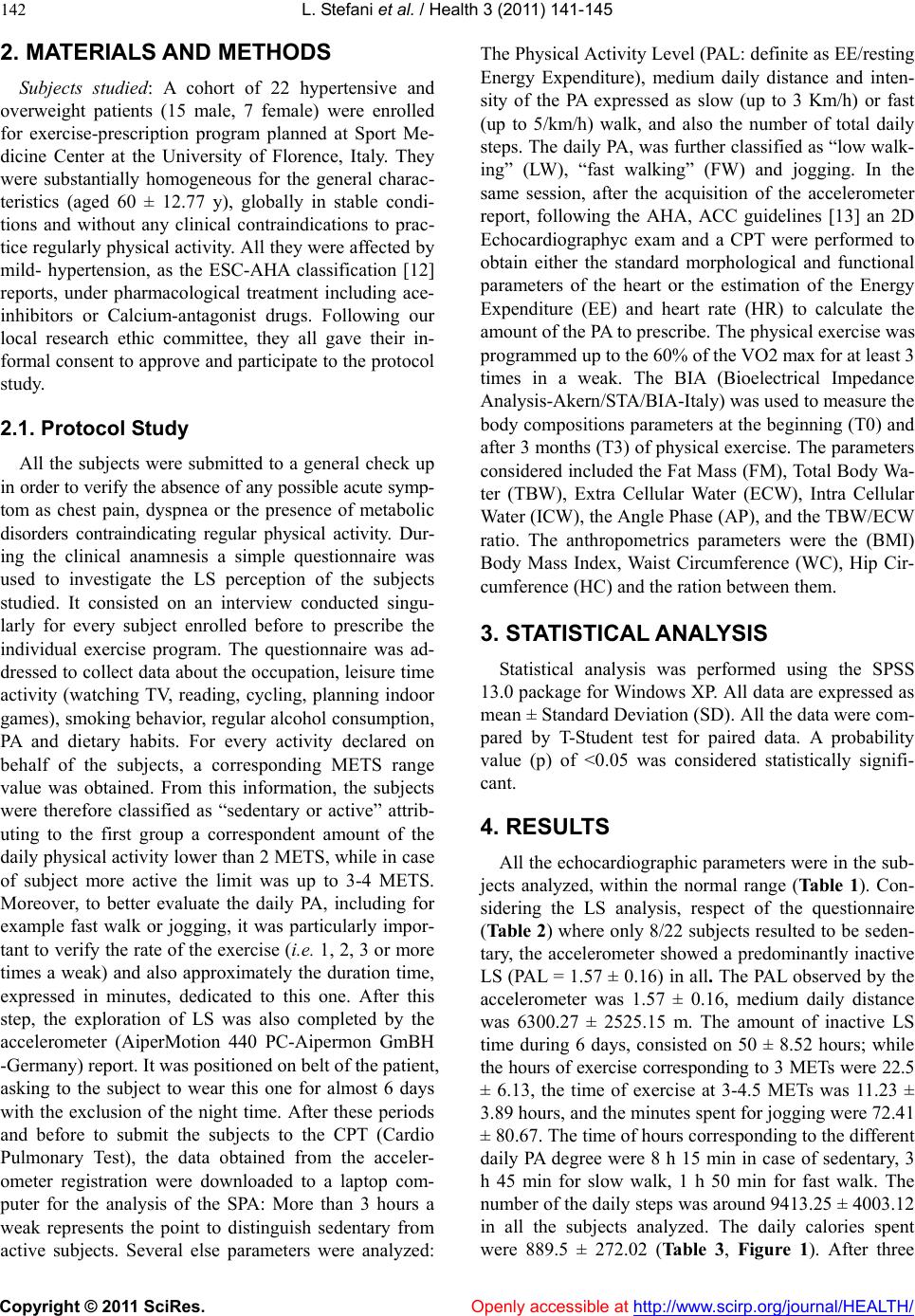

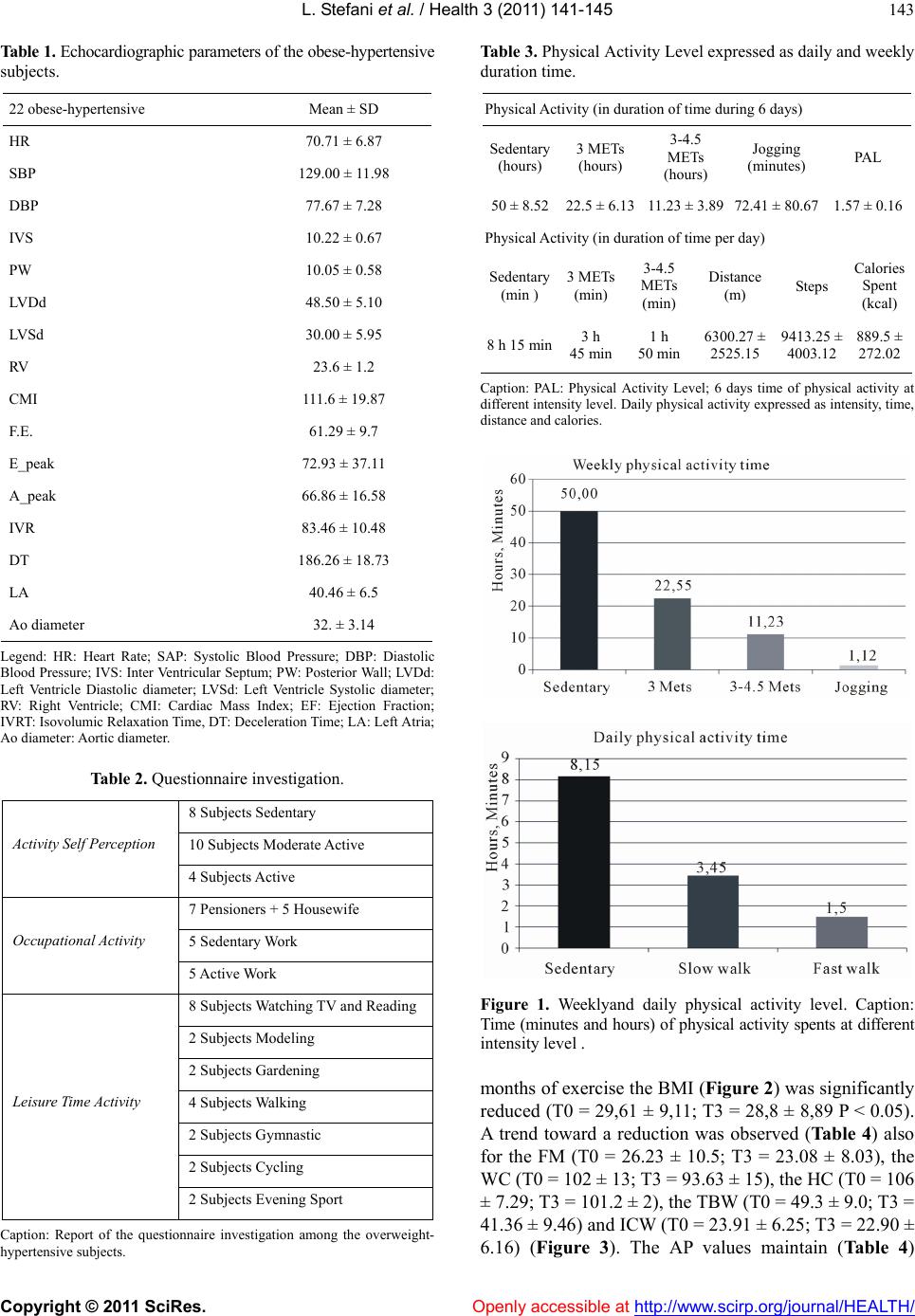

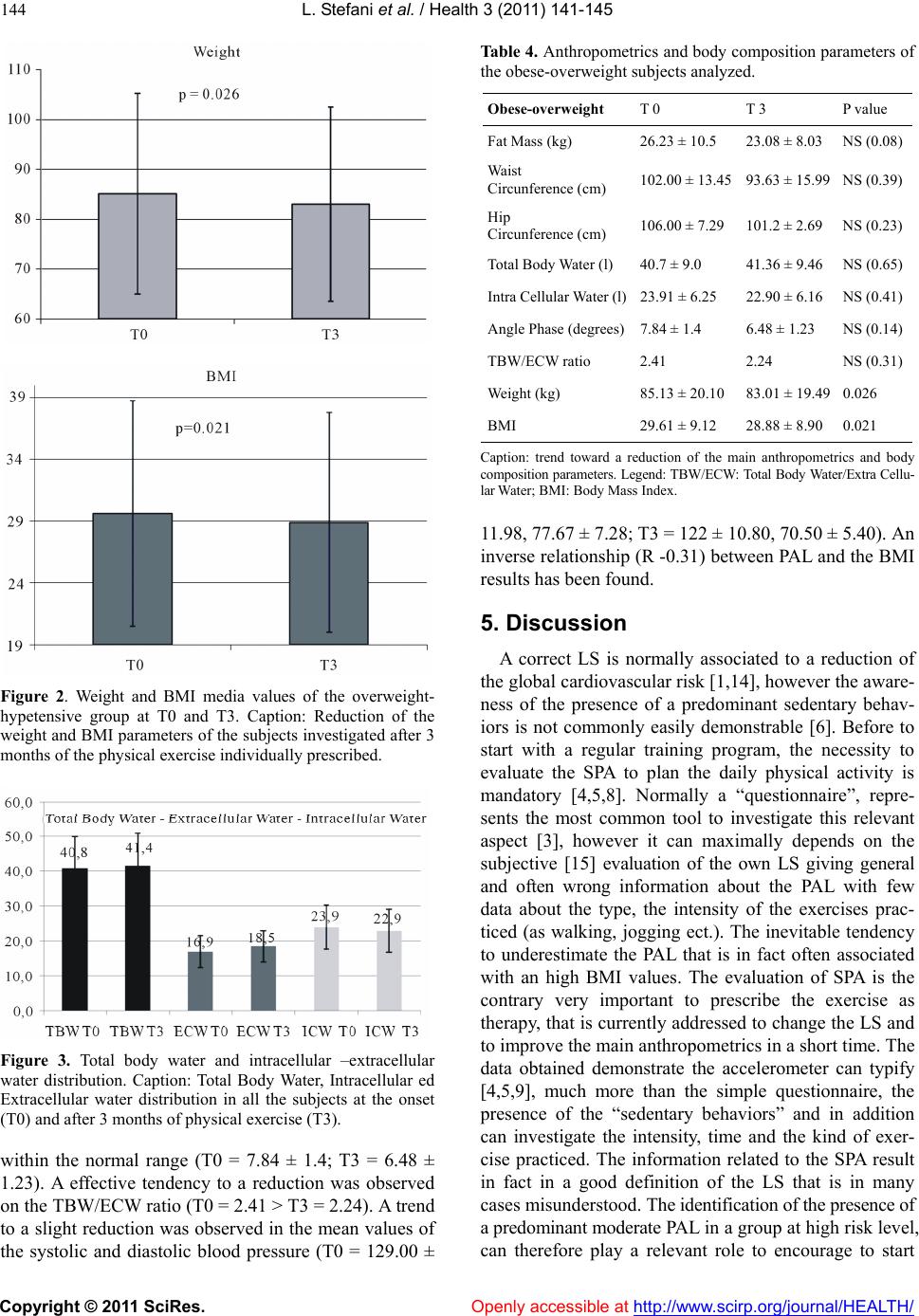

Journal Menu >>

Vol.3, No.3, 141-145 (2011) Health doi:10.4236/health.2011.33026 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Efficacy and educational role of a daily employment of the accelerometer to improve the life style in overweight-hypertensive population Laura Stefani*, Antonio Maone, Gabriele Mascherini, Irene Scacciati, Ilaria Corsani, Alessandro Gi- lardetti, Giulio Ciullini, Giorgio Galanti Sports Medicine Center, University of Florence, Florence, Italy; *Corresponding Author: laura.stefani@unifi.it Received December 14, 2010; revised February 23, 2011; accepted March 2, 2011. ABSTRACT The daily evaluation of the life style is funda- mental for the “exercise as prescription” to re- duce the cardiovascular risks factors. The regi- stration by an accelerometer can identify active from inactive subjects. The aim of the present study is to verify, in a small cohort of subject s a t high risk level (obese–hypertensive), the health outcomes. A group of 22 subjects were evalu- ated by the questionnaire and also by an accele- rometer positioned on belt for 5 days to estab- lish the daily Physical Activity Level (PAL).The anthropometrics parameters, Body Mass Index (BMI), Waist Circumference, Hip Circumference, Fat Mass, Free Fat Mass, Total Body–Intracellular and Extracellular Water and Phase Angle (PA) were measured at the beginning and after 3 months of regular exercise. The amount of the exercise prescribed for three months and at least 3 times in a weak, was determined by the Cardiopulmonary test at the 60% of the VO2. Statistical analysis included T-Student test for paired data with a significance at P < 0.05value. Respect of the questionnaire the accelerometer report showed a predominantly inactive life style (PAL = 1.49 ± 0.13). After three months the BMI was significantly reduced in all (p < 0.05) and in addition a trend toward a reduction was also observed for Fatty Mass and for the body composition parameters. The employment of the accelerometer is therefore associated to an improvement of the parameters strongly related with the cardiovascular risk. The results obt ained are suggestive for an educational role of this tool in subjects at high risk level. Keywords: Accelerometer; Life Style; Spontaneous Physical Activity; Body Composition and Phisycal Activity; Exercise as Prescription 1. INTRODUCTION In subjects at high risk level, a correct investigation of the daily Spontaneous Physical Activity (SPA) in term of time, frequency, intensity and kind of exercise can play a relevant role to plan the “exercise as prescription” pro- gram. The daily evaluation of the life style (LS) is fun- damental to distinguish “active” from “inactive” subjects and it normally represents the first step to establish the amount of the physical activity as therapy in order to contrast and therefore to reduce the global cardiovascu- lar risk [1,2] Currently, in addition to a simple question- naire, that summarily identifies sedentary from non- sedentary subjects [3], a longer period of registration by an accelerometer, can verify the effective SPA and quan- tify the time spends to practice exercise at different level of intensity [4,5]. It is note that the poor recognition of physical inactivity may be in fact an important barrier to the healthy behavior change [6]. The accelerometer can discover the presence of several “daily sedentary behav- iors “and therefore can play an educational role promot- ing an improvemen t of the own LS [7- 9]. I t is reasonable to think that this kind of approach, applied at the onset of a program of exercise as therapy and whose intensity is normally established and addressed to contrast the global cardiovascular risk of the subjects analyzed, can be helpful for a stronger of and objective realization of the real characteristics of own LS [10,11]. The aim of the study is to verify the role of the accelerometer in identi- fying sedentary behaviors and also to quantify the im- mediate positive impact on the improvement of th e main anthropometrics and body composition parameters, in a small cohort of overweight hypertensive subjects in consequence of the application of this popular tool for motivating their Physical Activity (PA).  L. Stefani et al. / Health 3 (2011) 141-145 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 142 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS Subjects studied: A cohort of 22 hypertensive and overweight patients (15 male, 7 female) were enrolled for exercise-prescription program planned at Sport Me- dicine Center at the University of Florence, Italy. They were substantially homogeneous for the general charac- teristics (aged 60 ± 12.77 y), globally in stable condi- tions and without any clinical contraindications to prac- tice regularly physical activity. All they were affected by mild- hypertension, as the ESC-AHA classification [12] reports, under pharmacological treatment including ace- inhibitors or Calcium-antagonist drugs. Following our local research ethic committee, they all gave their in- formal consent to approve and participate to th e protocol study. 2.1. Protocol Study All the subjects were submitted to a general check up in order to verify the absence of any possible acute symp- tom as chest pain, dyspnea or the presence of metabolic disorders contraindicating regular physical activity. Dur- ing the clinical anamnesis a simple questionnaire was used to investigate the LS perception of the subjects studied. It consisted on an interview conducted singu- larly for every subject enrolled before to prescribe the individual exercise program. The questionnaire was ad- dressed to co llect data about the occupation, leisu re time activity (watching TV, reading, cycling, planning indoor games), smoking behavior, regular alcohol consumption, PA and dietary habits. For every activity declared on behalf of the subjects, a corresponding METS range value was obtained. From this information, the subjects were therefore classified as “sedentary or active” attrib- uting to the first group a correspondent amount of the daily physical activity lower than 2 METS, while in case of subject more active the limit was up to 3-4 METS. Moreover, to better evaluate the daily PA, including for example fast walk or jogging, it was particularly impor- tant to verify the rate of the exercise (i.e. 1, 2, 3 or more times a weak) and also approximately the duration time, expressed in minutes, dedicated to this one. After this step, the exploration of LS was also completed by the accelerometer (AiperMotion 440 PC-Aipermon GmBH -Germany) report. It was positioned on belt of the patient, asking to the subject to wear this one for almost 6 days with the exclusion of the night time. After these periods and before to submit the subjects to the CPT (Cardio Pulmonary Test), the data obtained from the acceler- ometer registration were downloaded to a laptop com- puter for the analysis of the SPA: More than 3 hours a weak represents the point to distinguish sedentary from active subjects. Several else parameters were analyzed: The Physical Activity Level (PAL: definite as EE/resting Energy Expenditure), medium daily distance and inten- sity of the PA expressed as slow (up to 3 Km/h) or fast (up to 5/km/h) walk, and also the number of total daily steps. The daily PA, was further classified as “low walk- ing” (LW), “fast walking” (FW) and jogging. In the same session, after the acquisition of the accelerometer report, following the AHA, ACC guidelines [13] an 2D Echocardiographyc exam and a CPT were performed to obtain either the standard morphological and functional parameters of the heart or the estimation of the Energy Expenditure (EE) and heart rate (HR) to calculate the amount of the PA to prescribe. The physical exercise was programmed up to the 60% of the VO2 max for at least 3 times in a weak. The BIA (Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis-Akern/STA/BIA-Italy) was used to measure the body compositions parameters at the beginning (T0) and after 3 months (T3) of physical exercise. The parameters considered included the Fat Mass (FM), Total Body Wa- ter (TBW), Extra Cellular Water (ECW), Intra Cellular Water (ICW), the Angle Phase (AP), and the TBW/ECW ratio. The anthropometrics parameters were the (BMI) Body Mass Index, Waist Circumference (WC), Hip Cir- cumference (HC) and the ration between them. 3. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 13.0 package for Windows XP. All data are expressed as mean ± Standard Deviation (SD). All the data were com- pared by T-Student test for paired data. A probability value (p) of <0.05 was considered statistically signifi- cant. 4. RESULTS All the echocardiographic parameters were in the sub- jects analyzed, within the normal range (Ta bl e 1). Con- sidering the LS analysis, respect of the questionnaire (Tab le 2 ) where only 8/22 subjects resulted to be seden- tary, the accelerometer showed a predominantly inactive LS (PAL = 1.57 ± 0.16) in all. The PAL observed by the accelerometer was 1.57 ± 0.16, medium daily distance was 6300.27 ± 2525.15 m. The amount of inactive LS time during 6 days, consisted on 50 ± 8.52 hours; while the hours of exercise corresponding to 3 METs were 22.5 ± 6.13, the time of exercise at 3-4.5 METs was 11.23 ± 3.89 hours, and the minutes spent for jogging were 72.41 ± 80.67. The time of hours corresponding to the different daily PA degree were 8 h 15 min in case of sedentary, 3 h 45 min for slow walk, 1 h 50 min for fast walk. The number of the daily steps was around 9413 .25 ± 40 03.12 in all the subjects analyzed. The daily calories spent were 889.5 ± 272.02 (Table 3, Figure 1). After three  L. Stefani et al. / Health 3 (2011) 141-145 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 143 Table 1. Echocardiographic pa ra meter s of the o bese -hy pertensi ve subjects. 22 obese-hypertensive Mean ± SD HR 70.71 ± 6.87 SBP 129.00 ± 11.98 DBP 77.67 ± 7.28 IVS 10.22 ± 0.67 PW 10.05 ± 0.58 LVDd 48.50 ± 5.10 LVSd 30.00 ± 5.95 RV 23.6 ± 1.2 CMI 111.6 ± 19.87 F.E. 61.29 ± 9.7 E_peak 72.93 ± 37.11 A_peak 66.86 ± 16.58 IVR 83.46 ± 10.48 DT 186.26 ± 18.73 LA 40.46 ± 6.5 Ao diameter 32. ± 3.14 Legend: HR: Heart Rate; SAP: Systolic Blood Pressure; DBP: Diastolic Blood Pressure; IVS: Inter Ventricular Septum; PW: Posterior Wall; LVDd: Left Ventricle Diastolic diameter; LVSd: Left Ventricle Systolic diameter; RV: Right Ventricle; CMI: Cardiac Mass Index; EF: Ejection Fraction; IVRT: Isovolumic Relaxat ion Time, DT: Deceleration Time; LA: Left Atria; Ao diameter: Aortic diameter. Table 2. Questionnaire investigation. 8 Subjects Sedentary 10 Subjects Moderate Active Activity Self Perception 4 Subjects Active 7 Pensioners + 5 Housewife 5 Sedentary Work Occupational Activity 5 Active W ork 8 Subjects Watching TV and Reading 2 Subjects Modeling 2 Subjects Gardening 4 Subjects Walking 2 Subjects Gymnastic 2 Subjects Cycling Leisur e Time Activity 2 Subjects Evening Sport Caption: Report of the questionnaire investigation among the overweight- hypertensive subjects. Table 3. Physical Activity Level expressed as daily and weekly duration time. Physical Activity (in duration of time during 6 days ) Sedentary (hours) 3 METs (hours) 3-4.5 METs (hours) Jogging (minutes) PAL 50 ± 8.5222.5 ± 6.1311.23 ± 3.89 72.41 ± 80.67 1.57 ± 0.16 Physical Activity (in duration of time per day) Sedentary (min ) 3 METs (min) 3-4.5 METs (min) Distance (m) Steps Calories Spent (kcal) 8 h 15 min3 h 45 min1 h 50 min6300.27 ± 2525.15 9413.25 ± 4003.12 889.5 ± 272.02 Caption: PAL: Physical Activity Level; 6 days time of physical activity at different intensity level. Daily physical activity expressed as intensity, time, distance and calories. Figure 1. Weeklyand daily physical activity level. Caption: Time (minutes and hours) of phy sical activity spents at different intensity level . months of exercise the BMI (Figure 2) was significantly reduced (T0 = 29,61 ± 9,11; T3 = 28,8 ± 8,89 P < 0.05). A trend toward a reduction was observed (Ta ble 4) also for the FM (T0 = 26.23 ± 10.5; T3 = 23.08 ± 8.03), the WC (T0 = 102 ± 13; T3 = 93.63 ± 15), the HC (T0 = 106 ± 7.29; T3 = 10 1.2 ± 2) , th e TBW (T0 = 49.3 ± 9.0; T3 = 41.36 ± 9.46) and ICW (T0 = 23.91 ± 6.25; T3 = 22.90 ± 6.16) (Figure 3). The AP values maintain (Table 4)  L. Stefani et al. / Health 3 (2011) 141-145 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 144 Figure 2. Weight and BMI media values of the overweight- hypetensive group at T0 and T3. Caption: Reduction of the weight and BMI parameters of the subjects investigated after 3 months of the physical exercise individually prescribed. Figure 3. Total body water and intracellular –extracellular water distribution. Caption: Total Body Water, Intracellular ed Extracellular water distribution in all the subjects at the onset (T0) and after 3 months of physical exercise (T3). within the normal range (T0 = 7.84 ± 1.4; T3 = 6.48 ± 1.23). A effective tendency to a reduction was observed on the TBW/ECW ratio (T0 = 2.41 > T3 = 2.24). A trend to a slight reduction was observed in th e mean values of the systolic and diastolic blood pressure (T0 = 129.00 ± Table 4. Anthropometrics and body composition parameters of the obese-overweight subjects analyzed. Obese-overweight T 0 T 3 P value Fat Mass (kg) 26.23 ± 10.5 23.08 ± 8.03 NS (0.08) Waist Circunference (cm) 102.00 ± 13.45 93.63 ± 15.99NS (0.39) Hip Circunference (cm) 106.00 ± 7.29 101.2 ± 2.69 NS (0.23) Total Body Water (l) 40.7 ± 9.0 41.36 ± 9.46 NS (0.65) Intra Cellular Water (l)23.91 ± 6.25 22.90 ± 6.16 NS (0.41) Angle Phase (degrees)7.84 ± 1.4 6.48 ± 1.23 NS (0. 14) TBW/ECW ratio 2.41 2.24 NS (0.31) Weight (kg) 85.13 ± 20.10 83.01 ± 19.490.026 BMI 29.61 ± 9.12 28.88 ± 8.90 0.021 Caption: trend toward a reduction of the main anthropometrics and body composition parameters. Legend: TBW/ECW: Total Body Water/Extra Cellu- lar Water; BMI: Body Mass Index. 11.98, 77.67 ± 7.28; T3 = 122 ± 10.80, 70.50 ± 5.40). An inverse relationship (R -0.31) between PAL and the BMI results has been found. 5. Discussion A correct LS is normally associated to a reduction of the global cardiovascular risk [1,14], however the aware- ness of the presence of a predominant sedentary behav- iors is not commonly easily demonstrable [6]. Before to start with a regular training program, the necessity to evaluate the SPA to plan the daily physical activity is mandatory [4,5,8]. Normally a “questionnaire”, repre- sents the most common tool to investigate this relevant aspect [3], however it can maximally depends on the subjective [15] evaluation of the own LS giving general and often wrong information about the PAL with few data about the type, the intensity of the exercises prac- ticed (as walking, jogging ect.). The inevitable tendency to underestimate the PAL that is in fact often associated with an high BMI values. The evaluation of SPA is the contrary very important to prescribe the exercise as therapy, that is currently addressed to change the LS and to improve the main anthropometrics in a sho rt time. The data obtained demonstrate the accelerometer can typify [4,5,9], much more than the simple questionnaire, the presence of the “sedentary behaviors” and in addition can investigate the intensity, time and the kind of exer- cise practiced. The information related to the SPA result in fact in a good definition of the LS that is in many cases misunderstood. Th e i d ent ifi c a t i o n o f t h e p r ese n ce of a predominant moderate PA L in a group at high risk level, can therefore play a relevant role to encourage to start  L. Stefani et al. / Health 3 (2011) 141-145 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 145 with a “more adequate” PA program in subjects were the balancing of the moderate versus intense exercise is in agreement with the recent ACSM Guidelines [16]. All the values obtained h ave an inverse relationship with the intensity of the PA that cannot be evaluated by a simple questionnaire. According to the recent literatu re [17], the results demonstrate also the role of the accelerometer, to determine direct improvement in a short time of the pa- rameters strongly related with the cardiovascular risk. In conclusion the data support the glob al educational role in this context of the employment of the accelerometer that could be considered as an additional tool for the peri- odical assessment of the LS changes in order to enhance the empowerment on the exercise program. REFERENCES [1] Lee, I.-M. (2010) Physical activity and cardiac Protection. Exercise is Medicine, 9, 214-219. [2] Brown, A. and Siahpush, M. (2007) Risk factors for overweight and obesity: Results from the 2001 National Health Survey. Public Health, 121, 603-613. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2007.01.008 [3] HLAQ (1997) Historical leisure activity questionnaire. MSSE, 29, 43-45. [4] Bravata, D.M., Smith-Spangler, C. and Sundaram, V. (2007) Using pedometers to increase physical activity and improve health: A systematic review. JAMA, 298, 2296-2304. doi:10.1001/jama.298.19.2296 [5] Bassett, D.R., Wyatt, H., Thompson, H. and Peters, J. (2010) Pedometer-measured physical activity and health behaviors in US adults. MSSE, 42, 1819-1825. [6] Ronda, G., Van Asserrna, P. and Brug, J. (2001) Stages of change, psychological factors and awareness of physical activity levels in the Netherlands. Health Promotion In- ternational, 16, 305-314. doi:10.1093/heapro/16.4.305 [7] Klem, M.L., Wing, R.R., Mc Guire, M.T., Seagle, H.M. and Hill, J.O. (1997) A descriptive study of individuals successful at long-term maintenances of substantial weight loss. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 66, 239-246. [8] Melanson, E.L., Knoll, J.R. and Bell, M.L. (2004) Com- mercially available pedometers: Consideration for accu- rate step counting. Preventive Medicine, 39, 361-368. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.032 [9] Tudor-Locke, C.E., Ainsworth, B.E., Whitt, M.C., Thompson, R.W., Addy, C.L. and Jones, D. (2001) The relationship between pedometer-determined ambulatory activity and body composition variables. International Journal of Obesity, 25, 1571-1578. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0801783 [10] Bravata, D.M., Spangler, C.S., Sundaram, V., Gienger, A.L., Lin, N., Lewis, R., Stave, D.C ., Olk in, I. and Sira rd, J. (2007) Using pedometers to increase physical activity and improve health. JAMA, 19, 2296-2304. doi:10.1001/jama.298.19.2296 [11] Tudor-Locke, C. and Basset, D.R. (2004) How many steps/day are enough? Preliminary pedometers indices, for public health. Sports Medicine, 34, 1-8. [12] Mancia, G. and De Backer, G. (2007) The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of theEu- ropean Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the Euro- pean Society of Cardiology (ESC). European Heart Journal, 28, 1462-1536. [13] Cheitilin, M.D., Armstrong, W.F. and Aurigemma, G.R. (2003) ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 Guideline Update for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography: A Report of the American College of Cardiology, American Heart As- sociation Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, 16, 1091- 1110. doi:10.1016/S0894-7317(03)00685-0 [14] Lee, I.M. (2010) Physical Activity and cardiac protection. Current Sport Medicine, 9, 214-219. [15] Johnson, F., Cooke, L., Croker, H. and Wardle, J (2008) Changing perceptions of weightn Great Britain: Com- parison of two population surveys. BMJ, 337, 494. doi:10.1136/bmj.a494 [16] Donnelly, J.E., Blair, S.N., Jakicic, J.M. and Manore, M.M. (2009) Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. MSSE, 41, 459-471. [17] Tudor-Locke, C. and Lutes, L. (2009) Why Do Pedome- ters Work? A Reflection upon the factors related to suc- cessfully increasing physical activity. Sports Medicine, 39, 981-993. doi:10.2165/11319600-000000000-00000 |