Creative Education 2014. Vol.5, No.1, 36-45 Published Online January 2014 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2014.51008 OPEN ACCESS Health Quality Improvement Using Instructional Communication and Teamwork Videos: An Outcome Study Neil Cowie1, Angela Bowen2, Susan Kuling3, Kalyani Premkumar1, Mark Burbridge1, Jo celyne Martel1 1College of Mediicne, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada 2College of Nursing, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada 3Saskatoon Health Region, Saskatoon, Canada Email: 5string.neil@gmail.com Received December 15th, 2013; revised January 15th, 2014; accepted January 22nd, 2014 Copyright © 2014 Neil Cowie et al . This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons At- tribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual p roperty Neil Cowie et al. All Copyright © 2014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. Many factors contribute to errors that occur during emergency Cesarean birth under general anesthesia. The Joint Commission of Accreditation of Health Care Organizations (JACO) reports that 70% of sentinel events in obstetric practice are attributable to errors in communication and teamwork. Our objective was to develop a video training module to address these deficiencies, and measure its effectiveness. A web- based learning resource was created using professionally made videos that depicted effective and non-ef- fective communication/teamwork techniques in an obstetrical event. This resource could be accessed by a facilitator of small group sessions or by self directed learners. Obstetrical nurses watched this learning resource and were then debriefed by a facilitator to highlight examples of how human factors contribute to the evolution of adverse events. The knowledge and skills, as well as, perceptions of their own beha- viors and of other health professionals in the team, were evaluated pre- and post intervention. The per- formance of a subgroup of participants in a high-fidelity simulation of an emergency Cesarean birth was assessed to measure the outcome of intervention. Ninety-five obstetrical nurses were given the pre-inter- vention questionnaires, and 52 completed the post-intervention questionnaires one year later. Participants had significantly higher scores post-intervention (M = 0.78, SD = 0.09) as compared to pre-intervention (M = 0.73, SD = 0.12; t(53) = −3.07, p <0.003, d = .47). Following intervention, participants were more conscious of the behaviors of those they worked with (t(51) = −4.99, p < 0.001, d = −0.66). Ten months after intervention, nurses indicated that they were able to identify challenges in teamwork and communi- cation in their practice, and were more willing to speak up and be more assertive, and use strategies of conflict resolution and communication that they had learned. There was an improvement in performance of a sub-group of participant when assessed using a simulation scenario. The video web-based learning resource used in small group sessions effectively improved performance of obstetrical nurses as evaluated using questionnaires and high fidelity simulation. Future work will determine if the web-based version will be as effective in orienting new staff to the challenges of working in acute care obstetrical practice. Keywords: Simulation; Video Training; Nursing Education; Anesthesiologists; Obstetrics; Emergency Cesarean Birth; Communication; Teamwork; Human Factors; Health Quality Improvement; Web-Based Training; Acute Care Introduction Effective teamwork is a crucial defense against the evolution of adverse events in rapidly evolving critical clinical situations; this is never truer than in the labour and birth unit (Mann et al. 2006); when lack of communication or cooperation, it can have devastating effects on both mother and baby. Regional anesthesia (spinal and epidural) is recommended over general anesthesia for elective and all but the most urgent Cesarean birth as it reduces the likelihood of failed endotra- cheal intubation with resulting life-threatening complications (Practice Guidelines for Obstetric Anesthesia, 2007; Cyna, 2007; Bloom et al., 2005). Emergency Caesarean birth under primary gener al anesthesia is therefore a rare occurrence, (Tsen, 1998) and is often preceded by a life-threatening obstetrical event. Because of the paucity of exposure to such critical events, and because obstetrical teams seldom have the opportunity to practice and develop confidence together, patient safety is in peril every time a pregnant woman comes to the operating room for an emergency Cesarean birth. Undoubtedly, healthcare professionals are well trained in technical aspects of their profession. Unfortunately, creation of a team of experts does not ensure that the team will work coo- peratively towards a common goal of avoiding errors and main- taining health of the patient (Burke, 2004). To use an airline N. COWIE ET AL. OPEN ACCESS analogy, the modern jet aircraft “is too much airplane for one man to fly” (Stout, 1999). Interdisciplinary team failures that result in medical errors occurring because of the complexities of managing a sick patient, whic h require attention by more than one team member, are not appreciated by a leader who is operating solo (Burk, 2004). A well-functioning team effec- tively communicates, anticipates, shares their mental model, identifies and corrects errors in patient care that may lead to adverse events (Burke, 2004). In an effort to train practitioners to work more effectively in obstetrical teams, medical educa- tors have adapted the lessons learned in aviation’s cockpit re- source management (Helmreich, 1999) into high-fidelity medi- cal simulations (Draycott, 2006; Morgan, 2007; Blum 2005). Medical simulation is structured so that the performance of an interdisciplinary team in an artificial, but realistic scenario, can be observed and recorded (Gaba, 1993). Debriefing following the event serves as a powerful learning strategy that teams can use to improve future performance (Gaba, 1993). Background Health care has created tremendous improvements in quality of life, productivity, and longevity with a significant reduction in perinatal morbidity and mortality (McGlynn, 2003; Shaw, 1990; Saugstad, 2011). To Err is Human, a landmark publica- tion in 1999, by the Institute of Medicine in the United States describes two studies that measured adverse events during hos- pital admissions in New York, Colorado, and Utah. Adverse events were attributed to medical errors, 58% of the time in New York (2.9% of hospitalizations) and 53% in Colorado and Utah (3.7% of hospitalizations). When extrapolated across the United States, medical errors would account for 33.6 million hospital admissions in 1997, and 44,000 to 98,000 preventable deaths annually (Kohn, 1999). A similar scope of adverse events was reported in a review of hospital admissions in Can- ada. Of 2.5 million admissions in 2000, about 185,000 (7.5%) are associated with an unexpected adverse event, and 1.8% resulted in death (Baker, 2004). Of all adverse events, close to 70,000 (2.8%) of these were potentially preventable (Baker, 2004). In the United Kingdom the Confidential Enquiries into Ma- ternal and Child Health drew attention to substandard care that resulted in maternal and neonatal deaths: 36% to 67% of ma- ternal deaths resulted from substandard care from 2000-2002). The Joint Commission (Bloom, 2005), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (Joint Commission sentinel event alert #30, 2004), and the Institute of Medicine (Kohn, 1999) acknowledged that teamwork and communication were necessary components of a safe patient environment. The Joint Commission reported that failures in teamwork and communi- cation were among the leading causes of adverse obstetric events, and account for over 70% of sentinel events (Bloom, 2005). An example of how training obstetrical personnel in commu- nication and teamwork led to safer patient care was demon- strated by Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston (Mann, 2006). They initiated team training as a quality im- provement project. Using an adverse outcome index, patient safety improved by 47% in high-risk premature births. Mal- practice claims decreased by 50%, which prompted the insurer to reduce malpractice premiums by 10% for physicians who participated in teamwork training (Mann, 2006). Factors Contributing to Adverse Patient Outcomes Events leadi ng to fetal dist ress an d emerge nt Cesare an birth a re usually unexpected, but always lead to rapid assembly of a team usually including physicians, nurses, allied health care providers and trainee s, in what ofte n appea rs to be a cha otic frenzy of acti v- ity with team members unfamiliar with each other and their spe- cific roles. Staff who work in critical care environments may be technically competent, but individual performance is not enough to guarantee patient safety (Burke, 2004). A number of factors might provi de the “perfect s torm” for an adve rse obstetri cal event to occur include, local obstetrical anesthesia best-practice guide- lines favouring regional anesthesia, the rarity of emergent Cesa- rean births under general anesthesia, lack of team rehearsal, no role clarity or team expectations, as well as the time-pressure to deliver a heal thy baby before hy poxia results in irreversible b rain injury. For obstetrical nur ses, lack of practice and experience assisting with those ra re instances req uiring general a nesthesia in the preg- nant patient, can be anxiety-provokin g. Additionally, the practice of rotating non-obstetrical anesthesiologists through obstetrical call, as they would on any other surgical service, leads to a lack of familiarity with the skills of the nur ses, and a lack of familiarity of the nurses with anesthesiologist’s expectations at a time when team member s must wor k together in a time press ured, acute care situation. Apart from the se, a number of ot her factors contr ibuting to ad- verse patient outcomes have been identified in literature. These include situational awareness, communication, leadership, shared mental model, hierarchy, mutual support, conflict resolution and distraction, published as the evidence-based team training pro- gram “Team STEPPS™” (King, 2008). Situational Awareness Situational awareness is a perception of what is happening now, what the actual events mean and being aware of the direc- tion to which the situation could evolve (Endsley, 1995). Situa- tional awareness often depends on the previous experience of the health care provider (pattern recognition), and, as such, can vary considerably amongst team members with dire conse- quences for the patient (King, 2008; Klein, 2006; Kozlowski, 1998). Communication Team communication can be enhanced by use of concise, structured techniques such as SBAR-R (Situation, Background, Assessme nt, Recom mendati on and Response) (King, 2008; The Joint Commission, 2012; Institute for Healthcare Improve- ment.Web and action: using SBAR to improve communication, 2006; St Pierre, 2008). When using SBAR-R, the listener is first alerted to the importance of the conversation, which directs the listener to the critical nature of the problem. The sender then specifies the situation, background, and a suggested course of action, followed by a request for clarification of when the receiver will able to attend in person. Team members close the loop in communication, to ensure that the meaning of the mes- sage is understood, and demand feedback when a task is com- pleted. Leadership The leader takes charge of assignment of tasks, prioritization, re-evaluation, problem solving, and wise use of resources. Lis- N. COWIE ET AL. OPEN ACCESS tening, communicating back to the team, and maintaining an open environment where team members can report their con- cerns are the key attributes demonstrated by an effective leader (St Pierre, 2008). Shared Mental Model A common reason for misunderstanding occurs when team members fail to accurately share the mental model of what they perceive the situation to be. Misunderstanding can occur when one team member’s mental model and related plans for man- agement differ from those of the leader and other team mem- bers. Contributing factor s such as a lack of a ssertiveness in com- munication and the hierarchical nature of medical teams inter- fere with sharing one’s mental model (King, 2008; St Pierre, 2008). Hierarchy An effective team needs some hierarchy-where the leader di- rects the actions of the team. Junior members of the team may interpret the hierarchy as a barrier to speak up with important information, perhaps assuming the leader already knows what they know or fear of being criticized if their information con- tradicts what other team members perceive as correct (King, 2008; St Pierre, 2008). Mutual Support Mutual support protects team members from becoming overwhelmed or overloaded with tasks. Prioritization might already have been implemented by the leader, but there may also be physical limitations (e.g., chest compressions during a cardiac arrest) where a team member becomes fatigued or overloaded with tasks. Subsequently, another team member should step forward, acknowledge the situation, and offer their support or assign another team member to assist. In a similar way, cross-monitoring by each team member of each other’s performance will pick up and correct unsafe management be- fore a critical incident occurs (King, 2008; St Pierre, 2008). Conflict Resolution Lack of information or ineffective communication is a com- mon reason for conflict which can lead to divisiveness within a team. Tools such as DESC (Describing the problem concretely, describing the Emotional impact the problem has on the Sender, suggesting solutions and describing Consequences (King, 2008) and CUS (describing Concern, stating the event makes the sender feel Uncomfortable, or describing the patient Safety issue) are powerful methods to resolve conflict without con- frontation (King, 2008). The two-challenge rule (taught in avia- tion’s crew resource management) enables two team members to challenge a potentially unsafe act by a third member of the team (King, 2008). If acknowledged, but still unsuccessful, such a confrontation empowers the flight crew to take over the controls of the aircraft, or in the example of health care provid- ers to directly intervene or recruit a more senior colleague to take control. Distraction Distraction (too much focus on something else resulting in neglect of the current situation), and errors of fixation: this and only this (new information contrary to the present diagnosis is disregarded or not sought), everything but this, (continuing to order more tests without ever making a diagnosis) everything is OK (this event cannot be happening) have often been impli- cated in adverse events in both aviation and medicine (Hel- mreich, 1999). This is of equal importance to all team members, who, must not only be vigilant for breaches of care, but must assert their mental model (King, 2008). Existing Team Training Prog rams The World Health Organization (WHO) launched its “Safe Surgery Saves Lives” program in 2009 (Haynes, 2009). Intrin- sic to this program are paradigms of communication and team- work. In 2008, the Canadian Patient Safety Institute (Frank, 2008) developed six competencies that act as a framework for education in undergraduate, postgraduate and continuing pro- fessional development i.e., contribute to a culture of patient safety, work in teams for patient safety, communicate effec- tively for patient safety, manage safety risks, optimize human and environmental factors, recognize, respond to and disclose adverse events (Frank, 2008). In an attempt to address shortfalls in training of inter-professional teams, the American Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ) and the American Department of Defense developed and published Team STEPPS™ (King, 2008), that has been adopted by high risk organizations such as aviation, the military, healthcare, and the nuclear industry. This program consolidated teaching of human factors important to leadership, communication and teamwork into a portable, mul- timedia module. Medical simulation is another effective strategy used for team training. Medical Simulation grew out of an innovative, quality improvement program in aviation known as Crew Re- source Management (Helmreich, 1999) that has been utilized for decades to train airline pilots, in technical skills to avert dangerous events, and in non technical skills to improve lea- dership, communication and teamwork (Gaba, 1993). In medi- cal simulation, a medical case is recreated in a laboratory using a mannequin, with vital signs, and actors using appropriate dialogue (Gaba, 1993). Such simulations make it easier for students to suspend disbelief, and for the scenario to “come to life”. Following the experiential session, students participate in a debriefing where sense is made of the clinical events. The increased level of activation experienced in the lab translates to improved receptivity to alternative coping skills presented dur- ing the debriefing (circumplex model of emotion) (Feldman, 1999). Students are better able to change behavior if they first understand why they performed in a certain way. Local Experience In our institution, 10 - 12 of the 4000 births each year require primary general anesthesia to facilitate emergency surgery. Because of the rarity of emergency Cesarean birth under gener- al anesthesia (GA), nursing staff found it difficult to maintain skills and confidence in assisting anesthesiologists with emer- gency induction. Since high fidelity simulation has been effect- tive in other centres to facilitate team training in obstetrical care, it would have been logical for our centre to adopt this pathway. However, using such simulation to train all members of the obstetrical team in our hospital is not feasible because of li- mited physical resources, personnel, and financial support. In order to reach the greatest number of staff and trainees, we undertook to create a high quality video re-enactment of an  N. COWIE ET AL. OPEN ACCESS obstetrical event, and debrief participants as if they had partici- pated in an actual simulated event. Purpose The purpose of this study was to: a. Develop a web-based educational resource describing nurs- ing technical skills, teamwork and communication in a situ- ation requiring Cesarean birth under GA, and b. Evaluate the outcome of training obstetrical nurses using the developed resource. Methods Resource Development A professional film company was hired to create videos to de- pict two scenarios that portrayed the evolution of fetal distress and antepartum bleeding followed by an emergent Cesarean birth under general anesthesia. The first scenario used ineffective communica- tion and teamwork techniques, and the other demonstrated more effective ones. Each of the two videos was 13 minutes long. A summary of c ompetencies highlighted in t he videos are shown in Table 1. Videos were housed in a web-based interface along with links to library articles, other videos and pertinent web-based refer ence materials, that could be used for self-direc ted or facil itate d small group learning, described in web page (Premkumar, 2013). Intervention The nursing staff were trained during the designated educa- tional days allocated by hospital administration. During a 2-hour interactive workshop, participants watched the less-effective communication video. The first author (NC) ran video clips of the events that best demonstrated the skills and engaged the participants in discussion about human factors that adversely affect teamwork and communication. The second video about effective communication was run, and discussion highlighted reasons why the outcome was different using more effective techniques of communication and teamwork in the same scena- rio. All nurses were given the opportunity to review the self directed portion of the web-based resource after completion of this session. Evaluation Six months prior to the intervention, all obstetrical nursing staff (n = 95) were administered a questionnaire, which con- sisted of 14 items that reflected knowledge of the various re- sponsibilities of nurses (e.g., circulating, scrub, and anesthesia Table 1. Competencies demonstrated in video clips. Competency Definition Example Demonstrated in Vide o Clip Situational Awareness Conscious o bs ervation of one’s own environment and recognition of changing condition of the patient In the face of no neonatal t eam, failed intubation, ongoing hemorrhage, in the C/S un der GA, the anesthesiologist replies to the circulating nurse he doesn’t need any help SBAR-R Structured communication about a critical situation hat involves clear specification of Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation-Response S: The patient has abdominal pain, ble eding and fetal decelerations B: The pat i ent is a VBAC, had a functioning e pidural A: The pati ent might be rupturing her uterus R: We need the obstetrician to assess for a stat C/S R: When can I expect you? Closed Loop Communication Communication to a specific person that is acknowledged by the receiver and then affirmed by the sender The anest hesiologist s ays “make sure she’s tilted” , “give her some Oxygen”, without indi cating anyone in partic ul ar to perform the task. The tasks never get done. Leadership Assignment of tasks, prioritization, problem sol ving, acknowledge and listen to concerns of the team The obstetrician repeatedly asks when she can cut, because the anesthesiologist never gave specific ins tructions like “don’t make the incision until I say the word cut” Shared Mental Model Teams ability to articulate a common understanding of the problem and plan The birthing room nurse uses “call out” to alert the team that her patient has fetal decelerations, is bleeding and needs the obstetrici an to come now. Overcom e Hierarchy Every te am member, no matter how junior, should be assertive enough to bring forward new information that may challenge the team’s situational awareness The junior birthing room nurse does n ot persist in c onvincing the resident about seriousness of her patient’s situation, because she assumed the experienced resident already knew the situation, wasn’t conc erned, so why should she be concerned. Mutual Support Support to each team member should be f reely offered and freely sought when overload is recog ni zed throug h s ituational awareness The circulating nurse recognizes that there are more tasks to be done than team members available, s o when she phones for drugs and blood, s he asks the receiver to come to the OR because she ”needs another pair of hands” Conflict Resolution What is said is heard is understood. Use of SBARR, CUS and DESC, a nd t wo challenge rule The birthing room nurse and the charge nurse both try to convince t he resident unsuccessfully about the ser i ousness of the problem. The two- challenge rule would have empowe red them to seek help directly from the obstetrician. Avoid Distr action Fixation: this and only this, any t hing but this, everythin g i s ok Fixate on one thing, fail to receive new information Birthing room nurse fail s t o l isten to the f ather’s histor y about his wife’s sore throat following previous GA for C/S, because it happens at the same time as the fetal heart rate drops  N. COWIE ET AL. OPEN ACCESS assist nurse) and responsibilities of anesthesiologist in emer- gency Cesare an de liveries. They were also asked about knowledge of specific tasks, which health care professionals are responsible for performing (application of ECG leads and BP cuff, pre-oxygenation, appli- cation of cricoid pressure, application of BURP (Backward, Upward, Right sided Pressure on the larynx to bring the glottis into view during intubation). Eleven items questioned knowledge about the steps in diffi- cult airway management and the location of the difficult int u ba- tion cart, and understanding of the difficult airway algorithm. A further 15 items reflected interactions with the anesthesiologist such as: anesthesiologist knows who is assisting with induction, who determines prioritization, feelings of reluctance to speak up, ability to deliver information, role clarity, resource management, and recruitment of help. We also asked participants the length of time they practiced as a registered nurse, an obstetrical nurse, whether they worked in the Obstetrical operating room, and whether they had expe- rience with Cesarean birth under general anesthesia. An identical post-intervention questionnaire was administered immediately following the training sessi ons . Long term outcome of training was measured by written survey about lessons learned distributed to all participants approximately 10 months after training. Questions asked are listed in Table 2. Of 95 original participants, 52 co mpleted both the pre and post intervention questionnaires (see Figure 1). Volunteers who participated in simulated cases in the sim lab came from the 52 who had completed both questionnaires. Sampling adjustments due to attrition of participants who began the study, but did not complete the training or the post questionnaire is described in Figure 2. Simulation In order to study more in-depth the changes in communication and teamwork immediately after the intervention, eight partici- pants were recruited and divided into two teams of four nurses Table 2. Pre and post comparisons of items reflecting personal behavior. Item Pre M SD Post M SD Statistical Information I always tell the Anesthesiologist “I am the anesthesia assist” if I am 3.35 2.02 3.17 2.16 t(47) = 0.56, p = 0.575, d = 0.09 I always know how to organize and relay i nf ormation effectively during a stat Cesarean birth 3.78 1.74 3.68 1.45 t(49) = 0.32, p = 0.748, d = 0.06 When I am speaking to a doctor or another nurse, I am not always sure if they understood what I have said (Reverse Coded) 3.71 1.98 4.37 2.09 t(51) = −10.99, p = 0.053, d = −0.32 I understand my role as an anesthesia assist nurse during induction of general anesthesia 3.12 2.11 2.94 2.08 t(49) = 0.52, p = 0.608, d = 0.09 I do not speak up during a crisis situation because I do not think others in the room would listen to what I have to say (Reverse Coded) 3.38 1.97 3.64 2.15 t(49) = −0.78, p = 0.439, d = −0.13 I do not feel comfortable enough to speak up during a crisis situation because I am afraid of wha t the doctor wo ul d say back to me (Reverse Coded) 3.14 1.95 3.75 2.24 t(50) = −10.49, p = 0.142, d = −0.29 I know how to recruit other st aff to assist during an emergency 2.67 1.75 2.62 1.62 t(51) = 0.22, p = 0.824, d = 0.03 I understand my role w hen the anesthesiologist asks me to assist after inducti on is completed during emergency surgery 3.52 1.85 3.44 2.12 t(49) = 0.26, p = 0.800, d = 0.04 I always know who the nursing t eam leader i s during an emergency Cesarean birth after 1700 hours 3.53 1.87 3.65 2.25 t(48) = −0.34, p = 0.737, d = −0.06 Total 3.34 1.15 3.49 1.20 t(51) = −0.87, p = 0.387, d = −0.13 Figure 1. Study design. Figure 2. Sampling. N. COWIE ET AL. OPEN ACCESS each to participate in high fidelity simulation of events leading up to Cesarean birth under general anesthesia. Two additional scenarios were developed. The first depicted the onset of an eclamptic seizure during insertion spinal anesthetic for Cesa- rean birth for non-reassuring fetal heart tracing, necessitating emergency cesarean birth under GA. The anesthesiologist was inattentive. The second was a twin birth, where what was thought to be twin A’s tight nuchal cord, is clamped and cut, but following delivery of twin A it was determined that twin B’s cord had been cut leading to an urgent Cesarean birth to deliver twin B. The anesthesiologist in this scenario was also inattentive. Nurses were oriented to the simulation centre. They were told that they would be part of a nursing team that would man- age an obstetrical patient who required an urgent Cesarean birth. Team 1 enacted the first simulation Scenario over 15 minutes, and was immediately given the training session. Following intervention, team 1 then enacted the second Scenario over 15 minutes. Team 2 enacted the same two scenarios and training on a different day. Both scenarios were debriefed for each team by faculty from the simulation centre. Teams 1 and 2 watched their own performance in a video replay, created by B-Line Medical Simcapture (B-line Medical Sim capture). The record- ings were coded and delivered to four raters who scored the sessions using a Global Assessment of Obstetrical Team Per- formance (Tregunno, 2009, Morgan, 2011) (GAOTP). The raters reviewed a video of each simulation and independently rated it on whether various items pertaining to communication, teamwork, and situational awareness were met. In those situa- tions where there was marked variation between the raters, the videos were replayed, and the raters came to a consensus on scores. Ethics approval was obtained from the University Re- search Ethics Board and the local Health Region Ethics Board. All participants signed a written consent for the study. Statistical Analysis Descriptives were performed. Items about knowledge were coded as 1 for correct response and an incorrect response re- ceived a score of 0. Then, the means for all items pertaining to roles and other knowledge were calculated so that a mean score of 1.00 would indicate 100% accuracy in answering questions and .00 would indicate all questions were answered incorrectly. Items about the perceptions of behaviour were answered on a Likert scale of 1 (Strongly agree) to 9 (Strongly disagree), where lower scores reflected more positive behaviours. Of these items, nine questions reflected personal behaviours and six questions reflected the behavior of others. All analyses were done using SPSS (Becker, 2000). Paired-samples t-tests were conducted to compare the res- ponses given by nurses before and after the training session. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated, where 0.2 is consi- dered small, 0.5 is medium, and 0.8 is large. Descriptive statis- tics were calculated for the nurse follow-up survey. Descriptive statistics and t-tests were conducted using the SPSS Statistics 19 program. Effect sizes were calculated using an online calcu- lator (Becker, 2000). Results Participants Of the 52 nurses who completed both surveys, the majority (64.8%) had been a nurse for more than 15 years. Thirty-five percent of nurses had been an obstetrical nurse for greater than 15 years while 31.5% had been an obstetrical nurse for less than five years. The majority (83.3%) currently worked in the obste- trical OR. As well, most participants (77.8%) had assisted with a Cesarean birth under general anesthesia. During the six month period between administration of the pre-questionnaire and the intervention, 52 remained out of the original 95 nurses to undergo intervention and complete the post-questionnaire. Discrepancies in numbers were due to high staff turnover and leaves. In view of the ongoing turnover of nursing staff and in an effort to promote ongoing personal de- velopment, the participants were all given access to the web- based resources as self-directed learners after the study. Knowledge of Roles Nurses who attended the intervention answered significantly more questions correctly on the post intervention questionnaire (M = 0.95, SD = 0.05) than before (M = 0.85, SD = 0.09; t(53) = −8.19, p < 0.01, d = 1.38). This difference yielded a large effect size. Other Knowledge (Airway Related) Nurses attending the intervention session correctly answered signifi ca nt ly more items a fte r the se ssi on (M = 0.78, SD = 0.09) than before (M = 0.73, SD = 0.12; t(53) = -3.07, p < 0.003, d = 0.47). This difference yielded a medium effect size. Perceptions of Behaviour With regard to the nine questions that reflected personal be- haviours Cronbach’s α = 0.75 for pre, α = 0.73 for post and for the six questions that reflected the behaviour of others Cron- bach’s α = 0.65 for pre, α = 0.71 after the intervenion. No sta- tistically significant differences were found when comparing the responses on items pertaining only to personal behaviours and perceptions. However, there were significantly higher res- ponses after completing the training session (M = 4.53, SD = 1.17) than before (M = 3.73, SD = 1.27) about the behaviour of others, indicating that they were more critical of the behaviours of those they worked with (t(51) = −4.99, p < 0.001, d = −0.66). In pre intervention responses there was reluctance to speak up (M 3.85 sd 2.05), nursing input was not heeded (M 3.30 sd 1.99), evidence of a good working environment between nurs- ing, anesthesia and obstetrics (M 3.76, sd 1.51). See Table 3. Follow-Up Questi onnaire Ten months after the intervention, the nurses were asked to complete a follow-up questionnaire to determine if they were still able to apply the lessons learned to their practice. Four- teen nurses completed the questionnaire, 54% indicated that they now better understood how breakdown in communication and teamwork might lead to compromised patient safety. See Table 4. Simulation Raters used the GAOTP score for each of the videos of si- mulation. To test for reliability of raters, an intracl ass correlation coefficient was calculated. A high inter-rater reliability was  N. COWIE ET AL. OPEN ACCESS Table 3. Pre and post comparisons of items reflecting the behavior of the team. Item Pre M SD Post M SD Statistical Information The nursing team always receives clear direction from the anesthes iologist 3.43 1.69 4.31 1.68 t(50) = −3.35, p < 0.002, d = −0.52 The nursing team leader understands the role of each team member in the room during the Cesarean birth 3.04 1.61 3.61 1.69 t(48) = −2.22, p = 0.031, d = −0.35 After a stressful critical event, debriefing occurs with all involved staff 4.78 2.44 6.49 2.34 t(50) = −5.12, p < 0.001, d = −0.71 The health care provider who speaks to the anesthesiologist to alert them of an impeding stat Cesarean Birth is always familiar with the patient and the reason for the emergency 4.06 2.09 5.04 1.97 t(50) = −2.99, p = 0.004, d = −0.48 A good working environment exists between nurses, obstetricians, and anesthesiologists during stat Cesarean births under general anesthesia 3.82 1.59 4.14 1.50 t(49) = −1.16, p = 0.252, d = −0.21 The nursing team leader understands her role during a stat Cesarean birth under general anesthesia 3.08 1.57 3.51 1.50 t(48) = −1.62, p = 0.111, d = −0.28 Total 3.73 1.26 4.53 1.17 t(51) = −4.99, p < 0.001, d = −0.66 Table 4. Knowledge and team competencies in practice after 10 months. Competencies % Implemented It is OK for me to be more assertive if it means safer patient care 100 It is OK for me to speak up if I am aware of any threat to patient safety 100 Situational awareness and anticipation can improve patient safety 91 Using names and making eye contact i s a good way to ensure that a task is actually done 91 It is OK for m e to call for help on behalf of physicians if I think there is a threat to patient safety 82 Conflict can be resolved by emphasi zing how the situation is affecting you (I am concerned, I am uncomfortable, This is a patient safety issue) 82 Closing the loop bette r i nforms the leader that a t ask is completed or an order is understood 73 Knowing ahead of time what the steps the anesthesiologist mi ght us e during a fa i l ed intubation i mproves pat i ent safety 73 SBARR is a technique use ful in delivering organized information 64 Effectively sharing your mental model can improve patient safety 55 Knowing how best to apply cricoid pressure improves patient safety 55 Knowing how best to apply BURP improves patient safety 45 confirmed by a calculated Intraclass Correlation Coefficient of 0.97. Pre- and post scores for both teams reviewed in video from simulations were low which suggested the teams did not perform very well. Although not statistically significant, the trend showed that there was improved performance following the training. This was the first simulation experience the teams had encountered, and the teams found it difficult to react as they might have during a real clinical encounter. Teams found it unbelievable that an anesthesiologist would behave in such an inattentive fashion that would make it necessary for nurses to intervene on behalf of the anesthesiologist. Participants indi- cated that they enjoyed the experience, and requested that more opportunities be offered for simulation. They expressed that they gained a great deal of insight into their performance during the debriefing by watching videos of themselves. Personal communication from participants suggest that the video depicting ineffective communication evoked unpleasant emotions similar to those they had experienced when a similar event had happened to them in the past. We feel that even though they had not engaged in a simulated clinical event, that the emotional activation achieved by viewing this video placed them in a receptive learning state such that they were ready to listen to, and adopt, communication and teamwork strategies presented during the debriefing. Discussion Analysis of the questionnaires showed, that knowledge and skills significantly improved post intervention. Nurses’ know- N. COWIE ET AL. OPEN ACCESS ledge of the roles of the members of the team also improved following training. Nurses were more critical of the behaviour of both of themselves and of other team members, following the training. This might indicate that the training video intro- duced concepts that challenged pre-existing attitudes. Nurses had no prior training in human factors, team training, or com- munication skills on the labour and birth unit pertaining to ob- stetrical situations. The videos enabled participants to discover concrete consequences of ineffective communication and team- work styles. The follow-up survey of lessons learned, done 10 months af- ter the training, showed that respondents were able to: identify that challenges in teamwork and communication did exist in their practice, that they were more willing to speak up and be more assertive, use strategies of conflict resolution, and com- munication (closing the loop). Narrative responses reinforced data collected in the questionnaire. We were encouraged, that there was sufficient retention of the concepts given during the training session for the respondents to be positive in their res- ponses as late as 10 months post-intervention. Under powering the section of the study pertaining to simu- lation meant that any results comparing pre and post training would not have statistical significance. Still, low global scores did indicate reluctance to participate for various reasons. Per- formance in a simulation environment improves with practice. Since this was the first encounter, participants may not have understood our expectations. Interestingly, their disbelief that an anesthesiologist could behave in such an inattentive fashion may have prevented them from intervening on behalf of the anesthesiologist. That nurses enjoyed the experience, gained insight into their own performance during crisis management, and requested more educational experiences of this kind, motivates us to seek funding for ongoing educational initiatives. The behavioural portion of the questionnaire demonstrated reluctance of nursing staff to speak up or feel that their input was heeded. These concerns have been reported by investiga- tors using the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire te amwork climate scale (Sexton, 2006; Miller, 2008) in obstetrical practice. To our knowledge, this study is the first to test the principle of using professionally made, full-length video re-enactments of an obstetrical event in place of hands on simulation expe- rience to improve team performance. Our experience in doing this study demonstrated the magnitude of nursing turnover over one year, and the substantial difficulty nurse educators would have to keep their staff current on any topic has impact on de- veloping team skills. Further, limited time for educational events further curtails the opportunity for nurses to acquire team skills. Having a web-based educational module on com- munication and teamwork available, gives nurse educators an opportunity to present consistent training to new employees. The training module was found to make nurses more critical of the performance of anesthesiologists during emergency Ce- sarean birth under GA. Reluctance of obstetrical nursing staff to speak up or feel that their input was heeded by physicians is paralleled by reports from other tertiary care obstetrical centres (Sexton, 2006). Although we now have results from small group workshops using the teaching resource, we still do not have results on how effective self directed learning might be, using the web-based resource. Our expectation that is that the live performance of the group facilitator and the recorded, on-line debriefer com- menting on the video clips, is comparable. This will be eluci- dated in a future study. Limitations in This Study Small numbers of respondents who were trained and who submitted pre and post surveys, made interpretation of the re- sults difficult, even though the results were statistically signifi- cant. Since only 55% (n = 52) participants completed both pre and post intervention questionnaires, the remainder represented staff who left the unit permanently or who had gone on leave before the intervention. Work by Morgan et al. (Morgan, 2011), using the GAOTP determined that a minimum of eight evaluators were required to achieve a significantly reliable score. Because of our small simulation centre, we had limited faculty who could be evalua- tors. Our decision to use consensus on scoring increased in- ter-rater reliability above what it would have been had we not used consensus scoring. Pre and post scores for both teams were low which suggested the teams did not perform very well. This was the first simulation experience the teams had encountered, and the teams found it difficult to react as th ey might have during a real clinical encounter. Underpowering of the section of the study pertaining to simulation was primarily because of insuffi- cient funding to bring nurses in after hours to do simulation. Applications of the Learning Resource We have successfully used the training resource to deliver local, national and international workshops that improve under- standing of the importance of human factors in acute care teams. We are working towards making the web-based learning re- source available to other tertiary care obstetrical centres. It has already been implemented locally in the undergraduate nursing education program, and we hope soon to incorporate it into the undergraduate medical education program. For students who have had no simulation experience, these videos are valuable as “trigger” videos to encourage discussion of human factors prior to attending their first simulation experience. A disk containing the training module is published at MedEdPortal of the Ameri- can Association of Medical Colleges so that other training in- stitutions will have an opportunity to use it and make sugges- tions on how to improve it (Cowie et al., 2012). Conclusion The video-based learning resource appears to be valuable in improving knowledge and skills as well as heightening aware- ness of human factors that can hinder optimal team perfor- mance. Because of constant turnover of members of the obste- trical nursing staff over time, orientation of new members and continuing personal development of existing members, and us- ing the web-based learning resource, may provide an opportu- nity to keep the topics current, and impress upon members, the importance human factors that play in influencing optimal team- work and communication. REFERENCES American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Patient Safety and Quality Improvement. (2009). ACOG Committee Opinion No. 447: Patient Safety in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Ob- stetrics & Gynecology, 114, 1424.  N. COWIE ET AL. OPEN ACCESS http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c6f90e McGlynn, E. A., Asch, S. M., A dams , J., Keesey, J., Hicks, J., DeCris- tofaro, A., & Kerr, E. A. (2003). The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine, 348, 2635-2645. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa022615 B-line Medical Sim capture. (2009). http://www.blinemedical.com/solution/simcapture.aspx Baker, G. R., Norton, P. G., Flintoft, V., Blais, R., Bro wn, A., Cox, J., Etchells, E., Chali, W. A., Hebert, P., Majumdar, S. R., O’Beirne, M., Palacios-Derflingher, L., Reid, R. J., Sheps, S., & Ta mbl yn , R. (2004). The canadi an adverse events study: The incidence of adverse events among hospital patients in Canada, Canadian Medical Asso- ciation Journal, 170, 1678-1686. http://dx.doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1040498 Beaubien, J. M., & Baker, D. P. (2004). The use of simulation for train- ing teamwork skills in health care: How low can you go? Quality and Safety in Health Care, 13, I51-I56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2004.009845 Becker, L. A. (2000). Effect size calculators. http://www.uccs.edu/~faculty/lbecker/ Bloom, S. L., Spong, C. Y., Weiner, S. J., Landon, M. B., Rouse, D. J., Varner, M. W., Moawad, A. H., Caritis, S. N., Harper, M., Wapner, R. J., Sorokin, Y., Miodovnik, M., O’Sullivan, M. J., S ibai, B., Lan- ger, O., & Gabbe, S. G. (2005). Complications of anesthesia for ce- sarean delivery. Obstetr ics & Gynecolog y, 106, 281-287. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2004.009845 Blum, R. H., Raemer, D. B., Carroll, J. S., Duf resn e, R. L., & Cooper, J. B. (2005). A method for measuring the effectiveness of simulation- based team training for improving. BMJ Quality and Safety, 21, 78- 82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000296 Burke, C. S., Salas, E., Wilson-Donnelly, K., & Priest, H. (2004). How to turn a tea m of exp erts into an ex pe rt medical tea m: Guidance from the aviation and military communities, Quality and Safety in Health Care, 13, I96-I104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2004.009829 Gallagher, C. J., & Tan, M. (2010). The current status of simulation in the maintenance of certification in Anesthesia, International Anes- thesiology Clinics, 48, 83-99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AIA.0b013e3181eace5e Blum, R . H., Raemer, D. B., Car roll , J . S., Dufresne, R. L., & Cooper, J. B. (2005). A method for measuring the effectiveness of simulation- based team training for improving communication skills. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 100, 1375-1380. http://dx.doi.org/10.1213/01.ANE.0000148058.64834.80 Cowie, N., Premkumar, K., Bowen, A., Kuling, S., Kawchuk, J., Roo- ney, M., Morris, G., Burbridge, M., Martel, J., Sivertson, J., Camp- bell, D., Coupal, C., & Boechler, K. (2012). Teamwork and commu- nication in acute care: A teaching resource for health pratitioners. MedEdPortal. www.Mededportal.org/publications/9109 Cyna, A. M., & Dodd, J. (2007). Clin ical update: Obstetric anaesthesia. Lancet, 370, 640-642. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61320-8 Draycott, T., Sibanda, T. Ow en L, et al . (2006). Does training in obste- tric e mergencies improve neo natal outcome? BJOG: An Internation- al Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 113, 177-182. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00800.x Endsley, M. (1995). Toward a theory of situation awaren ess in d ynamic systems. Human Factors, 37, 32-64 http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA17244832&v=2.1& u=usaskmain&it=r&p=EAIM&sw=w&asid=9421978117a9483dbb4 c919d803b68c7 http://dx.doi.org/10.1518/001872095779049543 Barrett, L. F., & R ussell, J. A. (1999). Structure o f current affect. Cur- rent Directions in Psychological Science, 8, 11. Frank, J. R., & Brien, S. (2008) The safety competencies: Enhancing patient safety across the health professions. on behalf of The Safety Competencies Steering Co mmittee. Ottawa: Canadian Patient Safety Institute. Gaba, D., Fish, K. J., & Howard, S. K. (1993) Crisis management in anesthesiology, London: Churchill Livingston. Haynes, A. B., Weiser, T. G., Berry, W. R., Lipsitz, S. R., Breizat, A. H., Dellinger, E. P., Herbosa, T., Joseph, S., Kib atala, P. L., Lapitan, M. C., Merry, A. F., Moort hy, K., Reznick, R. K., Taylor, B., & Ga- wande, A. A. (200 9). A surgical safety checklist to red uce morbidity and mortality in a global population. The New England Journal of Medicine, 360, 491-499. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa0810119 Helmreich, R. L., Merritt, A. C., & Wilhelm, J. A. (1999). The evolu- tion of crew resource management training in commercial aviation. International j ournal of aviation psychology, 9, 19-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327108ijap0901_2 WHO. (2009). Human factors in patent safety review of topics and tools report for methods and measures working group of WHO pa- tent safety. www.who.int/entity/patientsafety/research/methods_measures/huma n_factors/human_factors_review.pdf Institute for Healthcare Improvement, SBAR Toolkit, (2011). http://www.ihi.org/knowledge/Pages/Tools/SBARToolkit.aspx Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. (2004). JCAHO sentinel event alert #30. King, H. B., Battle s, J., Baker, D. P., Alonso , A., Salas, E., Webster, J., Too me y, L., & Salisbury, M. (2008). Team STEPPS. Team strategies and tools to enhance performance and patient safety. In: K. Henrik- sen, J. B. Battles, M. A. Keyes, & M. L. Grady, (Eds.), Advances in patient safety: New directions and alternative approaches (Vol 3: performance and tools). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Re- search and Quality (US): Advances in Patient Safety. Klein, G., Moon , B., & Hoffman, R. R. (2006). Making sense of sense- making 1: Alternative persp ectives. IEEE In telligent S ystems, 2 1, 70- 73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/MIS.2006.75 Kohn, L.T., Corrigan, J. M., & Donaldson, M. S. (1999). To err is hu- man: Building a safer health system. Committee on Quality of Healt h Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Washington DC: National Academy Press. Kozlowski, S. W. J. (1998). Training and developing adaptive teams: Theory, principles, and research. In J . A. Cannon-Bowers, & E. Salas (Eds.), Making decisions under stress: Implications for individual and team training (pp. 115-153). Washington, DC: American Psy- chological Association. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10278-005 Miller, K. K., Riley, W., Davis, S., & Hansen, H. (20 08). In situ simu - lation. A method of experiential learning to pro mote safety and tea m behavior. Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing, 22, 105-113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.JPN.0000319096.97790.f7 Mann, S., Marcus, R., & Sachs, B. (2006). Lessons from the cockpit: GrandRounds: How team training can reduce errors on L&D. Con- temporary OB/GYN, 51, 34-36, 39-42. McGlynn, E. A., Asch, S. M., Ada ms, J., Keesey, J., Hicks, J., De cris- tofaro, A., & Kerr, E. (200 3). The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 348, 2635-2645. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa022615 Merien, A. E., v an de V en, J., Mol, B. W., Houterman, S., & Oei, S. G. (2010). Multidisciplinary team training in a simula tion set ting for acute obstetric emergencies: A systematic review. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 115, 1021-1031. Morgan, P. J., Pittini, R., Regehr, G., Marrs, C., & Haley, M. (2007). Evaluating teamwork in a simulated obstetric environment. Anesthe- siology, 106, 907-915. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.anes.0000265149.94190.04 Morgan, P. J., Tregunno, D., Pittini, R., Tarshi s, J., Regehr, G., Desou- sa, S., Kurrek, M., & Milne, K. (2012). Determination of the psy- chometric properties of a behavioral marking system for obstetrical team training using high-fidelity simulation. BMJ Quality & Safety, 21, 78-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000296 Practice guidelines for obstetric anesthesia: An updated report by the American society of anesthesiologists task force on obstetric anes- thesia. (2007). Anesthesiology, 106, 843-863. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.anes.0000264744.63275.10 Pre mku ma r, K., Cowie, N., Coupal, C. M., & Boechler, K. (2013). Software for annotating videos-A resource to facilitate active learn- ing in the digital age. Creative Education, 4, 465-469. Reason, J. (2000). Human error: Models and management. British Me- dical Journal, 320, 768-767.  N. COWIE ET AL. OPEN ACCESS http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768 Haynes, A. B., Weiser, T. G., et al. (2009). A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. New Eng- land Journal of Medicine, 360, 491-499. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa0810119 Salas, E., Si ms, D. E., Klein, C., & Burke, C. S. (2003). C an teamwork enhance patient safety? Forum Risk Management Foundation Har- vard Medical Institutions. www.rmf.harvard.edu/files/documents/Forum_V23N3_a3.pdf Saugstad, O. D. (2011). Reducing global neon atal mortalityis possible. Neonatology, 99, 250-257. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000320332 Sexton, J. B., Holzmueller, C. G., Pronovost, P. J., Thomas, E. J., McFerran, S., Nun es, J., Thompson, D. A., Knight, A. P., Penning, D. H., & Fox, H. E. (2 006). Variation in caregiver perceptions o f team- work climate in labor and delivery units. Journal of Perinatology, 26, 463-470. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211556 Shaw, C. D. (1990). Perioperative and perinatal death as measures for quality assurance. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 2, 235-241. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/2.3-4.235 St. Pierre, M., Hofinger, G., & Buerschaper, C. (2008). Crisis man- agement in acute care settings. Berlin: Springer. Stout, R. J., Cannon-Bowers, J. A., Salas, E., & Milanovich, D. M. (1999). Planning, shared mental models, and coordinated perfor- mance: An empirical link. Human Factors, 41, 61-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1518/001872099779577273 The confidential enquiry into maternal and child health, 7th annual report. (2000). Lo ndon: Maternal and ChildHealth Research Conso r- tium. http://adc.bmj.com/content/88/12/1034.full The Joint Commission center for transforming healthcare releases tar- geted solutions tool for hand-off communications. (2012). Joint Com- mission perspectives, 32, 1. Tregunno, D., Pittini, R., Haley, M., & Morgan, P. J. (2009). The de- velopment and usability of a behavioral marking system for perfor- mance assessment of obstetrical teams. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 18, 393-396. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2007.026146 Tsen, L. C., Pitner, R., & Cama n n, W. R. (1998). General anesthesia for cesarean section at a tertiary care hospital 1990-1995: Indications and implications. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia, 7, 147-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0959-289X(98)80001-0 Wass, V., Van d er Vleuten, C., Shatzer, J., & Jones, R. (2001). Assess- ment of clinical competence. Lancet, 357, 945-949. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04221-5

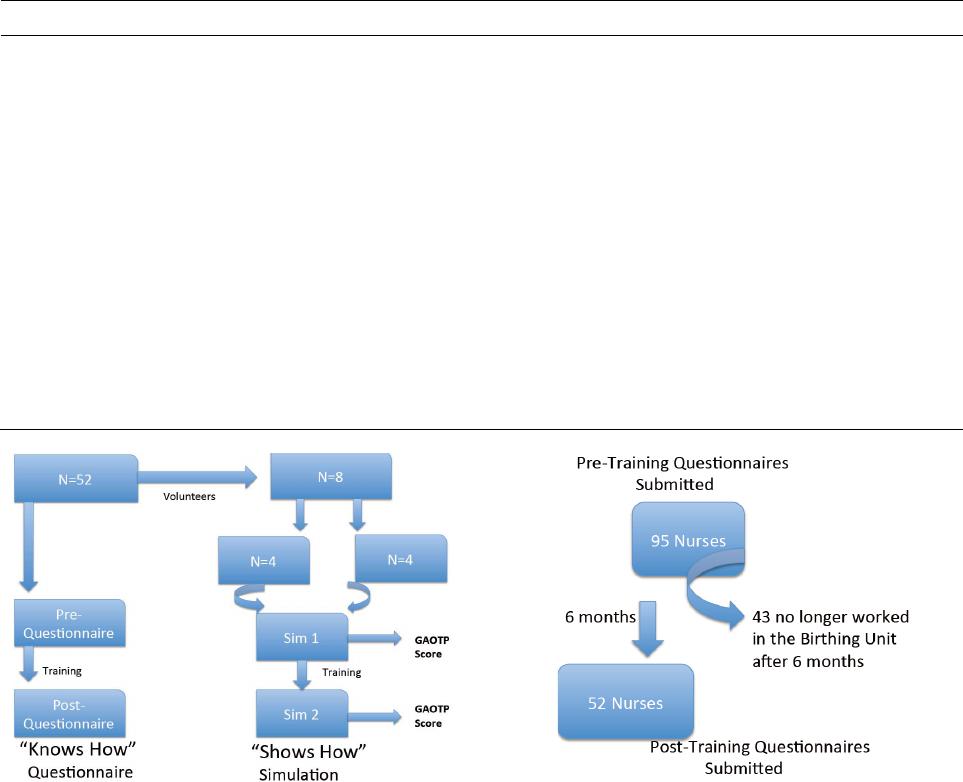

|