iBusiness, 2011, 3, 16-22 doi:10.4236/ib.2011.31003 Published Online March 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ib) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. iB The Effect of Knowledge Management on Product Innovation - Evidence from the Chinese Software Outsourcing Vendors* Dong Yang Department of Industrial Engineering, School of Economics and Management, XiDian University, Xi’an, China. Email: xjtuyd@163.com Received November 26th, 2010; revised December 16th, 2010; accepted December 20th, 2010. ABSTRACT The knowledge acquisition and exploitation are becoming more and more for local vendors in offshore outsourcing cooperation. In the process of product innovation, internal knowledge sharing (IKS), external knowledge acquisition (EKA) and their interactive relationship is discussed. Through the using of the method of 3SLS, the results of STATA indicate that IKS and EKA positively complement for product innovation. Furthermore, the result of SPSS reveals that knowledge exploitation mediates the (IKS) EKA and product innovation. Keywords: Knowledge Management, Innovation, Outsourcing Cooperation 1. Introduction Offshore outsourcing cooperation is becoming very popular among local vendors not only as an effective tool for market access but also as an effective means to learn from foreign buyers. Cooperation often entails a transfer of certain value-chain activities from foreign firms from the developed economies to local firms in the emerging economies such as China and India. In order to improve their innovation, the local vendors hope to improve their innovation through cooperation. In this case, knowledge acquisition is an integral part of local vendors’ motive to engage in internatio nal cooperation. Despite of the growing importance of offshore out- sourcing cooperation, there are some major limitations in the extant literature. The prior research emphasizes the importance of external knowledge acquisition, thereby ignoring the increasing importance of effect of the inter- nal relative knowledge on extern al knowledge in innova- tion process, which leads to the inefficient innovation. The impact of internal knowledge sharing and external knowledge acquisition on product innovation has not been studied in an integrated model [1]. Furthermore, knowledge creation does not necessarily lead to per- formance improvement or value creation, and the effi- ciency of knowledge exploitation should impact the in- novation and firms’ competitive advantages. Thus, it should be very important for firms to understand the ef- fect of relationship between the IKS (EKA) and exploita- tion on the innovation so that they can improve the effect of knowledge management on the product innovation efficiently. To fill these gaps, drawing on the perspectives of knowledge management and absorptive capabilities, we construct a theoretical framework to examine relation- ships among IKS (EKA), exploitation and product inno- vation from the view of Chinese vendors in outsourcing cooperation. Empirically, using 172 samples collected through face-to-face interviews of senior executives in Chinese firms, we examine the interactive relationship between IKS (EKA) and production, and test the medi- ating effect of kno wl e d ge exp l oi ta t i on. The paper proceeds as follows. First, by reviewing current literatures on knowledge management and ab- sorptive capacity, we present a conceptual model we used to examine the knowledge assimilation and exploi- tation processes. Next, we discuss the relationships be- tween IKS (EKA) and exploitation processes and product innovation, and present the hypotheses correspondingly. Third, we describe the study method and the empirical results, and finally we discuss our findings and offer concluding comments. * Supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Uni- versities(72105557).  The Effect of Knowledge Management on Product Innovation - Evidence from the Chinese Software Outsourcing Vendors17 2. Theoretic Background and Hypothesis Development Knowledge management has been defined as the process of identifying/creating, assimilating, and applying or- ganizational knowledge to exploit new opportunities and enhance organizational performance. To survive and keep competitive advantage in turbulent environment, local vendors must create know ledge or acq uire the know ledge about the outsourcing business and the customer’s needs. We define IKS as the process in which based on the rou- tines, different employees and units share, process, inter- pret and understand the knowledge. EKA refers to the process in which local vendors process, interpret and understand the knowledge from partners. IKS and EKA are two important knowledge sources that can be impor- tant source of innovation [2], and they play a key role in overcoming resistance to innovations and in the reduc- tion of uncertainty. Absorptive capacity is a firm’s ability to utilize exter- nally held knowledge thro ugh three sequential processes: 1) recognizing and understanding potentially valuable new knowledge from the partners through exploratory learning, 2) assimilating valuable new knowledge through transformative learning, and 3) using the acquired knowl- edge to create new knowledge and commercial outputs through exploitative learning [3]. The incentive mecha- nism, R&D intensity and customer’s knowledge within the firms influence the efficiency and the effectiveness of the firm’s absorptive capacity [4]. External environment factors, such as outsourcing environment, knowledge produced by partners, also influence on absorptive ca- pacity. Absorptive capacity will influence on external knowledge acquisition and exploitation. Absorptive ca- pacity influence commercial outputs (products, services, and patents) and knowledge outputs [5]. The success of the commercial outputs and the new knowledge created can influence the future investment in absorptive capac- ity. IKS increases member interaction and facilitates the free flow of knowledge. The process involves social in- teractions among individuals using internal communica- tion channels for knowledge transfer to arrive at a com- mon understanding. Where organizational units hold specialized knowledge, inter-unit linkages are the pri- mary means of transferring the customer’s knowledge [6]. The higher level of internal knowledge is helpful for firms to understand and acquire the customer’s knowl- edge. External knowledge sources enable the firms to develop need ed capabilities quick ly, leading to flexibility and reducing costs. EKA also can help firms accumulate relevant experiences and routines for knowledge sharing and interpretation, thus which can promote the local firm’s absorptive capabilities [7]. 2.1. IKS and EKA as Complements IKS emphasizes to build routines and norms, communi- cate and share knowledge from different units, while EKA pertains to availability of channels for securing knowledge and to the possibility of understanding and exploiting external knowledge. Furthermore, they inter- act with each other as complements. First, to create more value from IKS, firms should in- tegrate the knowledge resources in which effectively combine the knowledge [8]. IKS can be regarded as one of integrative capabilities [9 ], and it helps firms build the reputation in the outsourcing market, as the customers (buyers) are more willing to collaborate with the firms having a higher level of internal capabilities [8]. Thus, the higher level of IKS is helpful for firms have more access to the customer’s knowledge about technology and marketing. Additionally, a higher leve l of IKS stands for higher level of absorptive capacity, which helps firms learn more from their partners and create more value from the opportunities provided by their partners [3]. Thus, if an employee or unit cooperates closely with other employees or units, norms of cooperation will be established. These norms are reflected in the process of EKA as well. Therefore, in the process of IKS, firms can build good norms of knowledge transferring and sharing, which also leads to easily acquire the knowledge from partners. Second, in the process of EKA from the customers, firms can recognize and find opportunities, and learn the routines about knowledge sharing and transferring from the customer, which can enhance the capabilities of knowledge management [6]. The capabilities enhance- ment of the firm mitigates the obstacle to knowledge sharing between different units inside the firm. Therefore, through EKA, firms can reduce the costs of knowledge coordination, and then IKS becomes more effective. In order to be effective in external cooperation, organiza- tions need well-functioning internal interfaces. The rou- tines of external cooperation also directly influence the efficiency and efficacy of the internal sharing vice versa. Thus, in the process of EKA, firms can also promote the IKS. Furthermore, in the context of dynamic environment, IKS are not enough for firms to implement innovation, since they are very likely to be deficient of complemen- tary knowledge. In order for firms to fully extract value from their IKS, firms should have outsourcing coopera- tion through which they can mobilize complementary external knowledge and identify more rewarding oppor- tunities. IKS can help the firms to use the complementary external knowledge that can be obtained on the basis of EKA. Lacking IKS, firms may have difficulty in gener- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. iB  The Effect of Knowledge Management on Product Innovation - Evidence from the Chinese Software Outsourcing Vendors 18 ating value from their EKA. Therefore, we suggest: H1a: increases in IKS will enhance the level of EKA. H1b: increases in EKA will enhance the level of IKS. H1c: IKS and EKA will complement for product inno- vation. 2.2. The Mediating Effect of Knowledge Exploitation The abundance o f knowledge resources do es not guaran- tee that the firms will excel in, or practice, effective in- novation, and efficient exploitation of knowledge is key work of obtaining good performance. Especially, if lack- ing the capabilities of knowledge exploitation, firms will have obstacle in product innovation [10]. Only interpret- ing and exploiting the knowledge, firms can promote innovation. Through efficiently exploiting knowledge, firms can leverage and recombine the knowledge to pursue product line extension or new product development. In the proc- ess of the knowledge exploitation, firms can enhance innovation capabilities, which through the process of bi- sociation, help firms to develop new schema or chan ges to existing process. Furthermore, firms can convert these changes into innovation product [11]. After integrating the knowledge, firms can fully and systematically apply the knowledge of different units. Therefore, quickly in- tegrating the knowledge from different units inside firm, firm can reduce the cost of process. Comparing with the other vendors, the firm can have the higher level of in- novation. In the process of knowledge exploitation, firms can also develop the new technological and market capa- bilities. The development of functional capabilities can promote R&D and understand the customer’s needs, which is helpful for product innovation. Finally, through effective knowledge exploitation, firms can improve their flexibility in grasping the opportunities, which makes firms have advantage in product innovation [12]. H2: The knowledge exploitation has a mediating effect on knowledge assimilation and product innovation. 3. Methodology 3.1. Sample and Data Collection To test the hypotheses, a questionnaire survey research method was used to search responses from some soft- ware firms with offshore outsourcing cooperation in the Shaanxi and Shandong provinces of China. A total of 300 local firms involved in offshore outsourcing coop- eration were selected from the list provided by the local government agencies. We had three sampling criteria: the firms had to be 1) at least engaging in offshore outsourc- ing cooperation with 3 years; 2) at least 30 employees. A total of 211 questionnaires were collected, and other 89 firms could not provide their information due to such reasons as their mergers and acquisitions, business changes, and turnover of top management team, among others. Out of 211 returns, a total of 172 firms provided complete data. The data was collected in the summer of 2009. Therefore, 172 enterprises had all the necessary data. The effective rate was 57.73 percent (172 out of 300). Two commonly raised issues concerning survey methodology are non-response bias and common method variance. Using t-tests, we compared the responding firms with 89 non-responding firms as well as 39 firms whose data could not be used with respect to the firm attributes of firm size, ownership status, and sales based on the public data from the Statistical Yearbook and the Directory of Enterprises at the provincial level. None of the t-statistics was significant. To further verify if our sample was representative of the whole population, we compared the sample’s firm size, ownership status and sales to those of the national population using the infor- mation from the China Statistical Yearbook at the na- tional level. Again, none of the t-statistics was significant. Also due to the relatively high responding rate, we did expect any non-response bias in the data of this study. 3.2. Measurement We consulted the extant literature to compile measure- ment items. As noted some items were modified to re- flect the specific context of the study. New questions were developed based on a review of the inter-firm co- operation literature. All constructs were measured by the average of the responses, on a 7-point Likert scale. IKS: Following the work of Chen and Huang (2007) [13], we measure the IKS with five items. The items in- clude: 1) corporate managers share the information about customers with employees; 2) employees will transfer the information of customers to managers; 3) different units have stronger aspiration to learning each other; 4) em- ployees can easily share the knowledge; and 5) firms encourage employees from different units and hierarchy to share knowledge; 6) encourage employees to partici- pate in decision making; 7) encourage employees to learn through teaching, guidance, and training. EKA: Based primarily on a measurement instrument created and validated by Lyles and Salk (1996) [14], we adjusted their measures to fit our research better. Four indicators used here are: through cooperation, we have acquired much knowledge from partners, they are: 1) new technological expertise; 2) new marketing expertise; 3) manufacturing process; and 4) experience in the en- trance of new market. Knowledge exploitation: following the work of Song et al. (2005) [15] and Chen and Huang (2007) [13], we Copyright © 2011 SciRes. iB  The Effect of Knowledge Management on Product Innovation - Evidence from the Chinese Software Outsourcing Vendors Copyright © 2011 SciRes. iB 19 measure the knowledge exploitation with five items. They are 1) a strong emphasis to put know-how, patents, and new product designs into practice; 2) a strong ten- dency to use the advanced technologies introduced into firm; 3) a strong tendency to adopt the advanced man- agement techniques introduced into firm; and 4) a strong tendency to employ various experts introduced into firm; 5) a strong tendency to employ various experts intro- duced into firm. Product innovation: following the work of Danneels and Kleinschmidt (2001) [16], we measure the product innovation with fo ur ite ms. Four ind icator s u sed h ere are: 1) develop a large number of types of new product; 2) improve the quality of the products; 3) expedite the in- troduction of these new products to the market; 4) intro- duce a large number of process technologies. 3.3. Reliability Analysis Initially, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with the SPSS was used to purify the original measures (total of 20 items), and the measures showed evidence of validity and reliability once items with low loadings and high cross loadings were eliminated. This process resulted in the retention of 16 of the original 20 items. A confirma- tory factor analysis (CFA) by means of LISREL 8.54 was also conducted to further validate the measures. All items from the EFA remain in the final measurement model, which demon st rates good fit. Composite reliability assesses the inter-item consis- tency, which was operationalized using the internal con- sistency method that is estimated using Cronbach’s alpha. Typically, reliability coefficients of 0.70 or higher are considered adequate [17]. Therefore, an alpha value of 0.70 was considered as the cut-off value. In Table 1, Cronbach’s alpha values of all factors were above 0.70. These results suggest that the theoretical constructs ex- hibit good psychometric properties. 3.4. Method of Analysis Since the hypotheses involve mutual relationship be- tween IKA and EKA, the relationship between inde- pendent variables and dependent variables is blurred. Thereby, we need to test two equations simultaneously. First, we must test whether EKA is influenced by IKA. Second, and simultaneously, we must test whether IKA is influenced by EKA. Specifying and testing these two equations independently would, of course, introduce sig- nificantly biased estimates du e to the endogeneity of key independent variables (IKA and EKA) in all equations and due to common disturbances across equations. In order to eliminate the effects on regression estima- tion by endogenous variables, our econometric approach is a simultaneous equation estimation using a three-stage least squares method. This method uses generalized least squares (GLS) on the basis of two stages least squares (2SLS) to test equations simultaneously, then resolves Table 1. Construct factors. Factors Variables Loading alpha Corporate manage rs share the inform ation about customers wi t h employees 0.710 Employees will transfer the information of customers to man- agers 0.709 Different units have stronger aspiration to learning from each other 0.761 Employees can easily sh are the knowledge 0.807 Internal Knowledge Sharing Firms encourage employees from different units and hierarchy to share knowledge 0.732 0.762 new technological expertise 0.804 new marketing expertise 0.886 manufacturing process 0.892 External Knowledge Acquisition experience in the entrance of new market 0.805 0.882 a strong emphasis to put know-how, patents, and new pr o d u c t designs into practice; 0.711 a strong tendency to u s e t h e advanced technologies introduced into firm; 0.807 a strong tendency to adopt t h e advanced management tech- niques introduced into firm; 0.781 Knowledge Exploitation a strong tendency to em ploy various expert s in t roduced into firm; 0.771 0.829 develop a large number ty pes of new produ ct 0.829 improve the quality of the products 0.824 Product Innovation expedite the introduction of th e se n ew products to the market 0.821 0.809  The Effect of Knowledge Management on Product Innovation - Evidence from the Chinese Software Outsourcing Vendors 20 the problem of relativity between endogenous variables random disturbances (Stata, 1999). Stage 1 of this pro- cedure can be thought of as producing instrumented val- ues of all endogenous variables. These instrumented val ues are essentially predicted values generated by the re- gression of each endogenous variable on all exogenous variables in the system. Stage 2 produces a consistent estimate of the covariance matrix of the equation distur- bances. Estimates are obtained from the residuals pro- duced from a two-stage least squares estimation of each structural equation. Finally, Stage 3 performs a GLS-type estimation using the covariance matrix from Stage 2 and with the instrumental values replacing all endogenous right-hand side variables. By correctly specifying this system of equations, we can test for a pattern of complementarity between IKA and EKA. If IKA positively affects EKA and EKA posi- tively affects IKA, their complementarity is supported. We adopt the software of STATA to demonstrate this proposition. In order to test the mediate relationship of knowledge exploitation between IKS and EKA and product innova- tion, we establish regression equation in which firms’ product innovation is dependent variable and IKS, EKA and knowledge expl oi t at i on are depen dent variables. Then we use SPSS to estimate the coefficients of equation. 3.5. Analysis and Results The descriptive statistics in Table 2 show basic informa- tion on each factor and correlations among these factors. Table 3 and Table 4 present the results. In Table 3, the critical test of the relationship, as complements be- tween IKS and EKA, hinges on the sign and significance of coefficients for IKS and EKA in the two equations. Positive coefficients suggest a complementary relation- ship in which IKS predicts greater EKA and greater EKA predicts greater IKS. Consistent with our hypothesis of a complementary relationship, we find that increases in the level of IKS are associated with greater levels of EKA (Hypothesis 1a, see Equation (1)) and that increases in the level of EKA are associated with greater levels of IKS (Hypothesis1b, see Equation (2)). In Table 4, Model 1 and Model 4 are the base models that include only the control variables. Adopting the procedure r ecommend ed by Bar on and K enny (19 86) , we tested the mediating effect of knowledge exploitation on IKS,EKA and product innovation relationship. In the first step, the dependent variable, product innovation, was regressed on the independent variable of IKS and EKA. As shown in Model 2, IKS and EKA have signifi- Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Pearson Correlation Matrix (N = 172). Variables Mean S.D. 1 2 3 4 5 6 1.Firm size 3.3451.459 1 2 In industry the rate of new products is high 4.0831.532 0.148 1 3.Internal knowledge a ssimilation (I KS) 4. 59 80.828 0.082 0.301** 1 4.External knowledge a ssimilation (EKA) 3.5351.709 0.063 0.085* 0.171** 1 5.Knowledge exploitation 3.7521.123 0.092** 0.163** 0.308** 0.188** 1 6.Product innovation 4.4471.079 0.081 0.182** 0.277** 0.131** 0.564** 1 Table 3. Assessing the determinants and complementar ity of IKS and EKA. Determinants of EKA Determinants of IKS Variables Equation 1 Equation 2 Internal knowledge assimilation (IKS) 0.657* External knowledge assimilation(EKA) 0.213*** Firm size 0.092 0.037 In industry the rate of new products is high 0.019 0.093** Constant 1.251 1.301 N 172 172 Chi-square 124.341 183.626 F-value P-value 0.000 0.000 R-square 0.133 0.158 +p<0.10; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. iB  The Effect of Knowledge Management on Product Innovation - Evidence from the Chinese Software Outsourcing Vendors21 Table 4. Results of OLS Regression (N = 172). Product Innovation Knowledge exploitation Dependent variable Model 1 Model 2 Mo de l 3 Model 4 Model 5 Size 0.082** 0.077** 0.039 0.103** 0.097** In industry the rate of new products is high 0.110*** 0.103* 0.062* 0.091*** 0.047 Internal knowledge assimilation (IKS) 0.285*** 0.006 0.347*** External knowledge assimilation (E KA) 0.201*** 0.003 0.336*** Knowledge exploitation 0.471*** R Square 0.061 0.115 0.347 0.103 0.155 F Value 13.235*** 15.846*** 49.123*** 14.003*** 20.133*** +p<0.10; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 cant positive effect on product innovation. Therefore, it supports the Hypothesis1c. In the second step, the me- diator of knowledge exploitation was regressed on the independent variable of IKS and EKA. The result shown in Model 5 indicates that IKS and EKA have a signifi- cant positive impact on knowledge exploitation (β = 0.347, p < 0.001, β = 0.336, p < 0.001). The third step was to examine the relationship between the mediator and the dependent variable. The result shown in Model 3 indicates that knowledge exploitation has a significant positive effect on product innovation (β = 0.471, p < 0.001). At the same time, the impact of IKS on product innovation becomes not significant anymore (β = 0.006), which indicates a full mediation effect. Similarly, knowl- edge exploitation also has a full mediation effect on the relationship between EKA and product innovation. Taken in whole, hypothesis 2 is suppo rted. 4. Discussion Based on knowledge management perspective, this paper studies the relationship between IKS and EKA, knowl- edge exploitation and product innovation. The comple- ment relationship between IKS and EKA is discussed. Furthermore, we also test the mediating effect of knowl- edge exploitation on the relationship between IKS (EKA) and product innovation. Under turbulent environment and intern ational compe- tition, to implement indigenous innovation strategy, Chinese firms should search for technology and market knowledge in time. However, the abundance of manu- facturing resources does not guarantee that the firm will excel in, or practice, effective manufacturing integration (Hitt, Hoskisson, and Nixon, 1993). Chinese firms should understand that knowledge creation and assimilation is necessary for innovation, but not sufficient. In the proc- ess of product innovation, firms should emphasize the knowledge exploitation. Second, IKS and EKA are important knowledge source mode. Firms should encourage every employee and unit to share the knowledge through necessary award. Communication in different units can enhance the effi- ciency of assimilation of the external knowledge. The good relationship with suppliers, customers and universi- ties will lead firms to have access to many skill and ex- periences. Hence, EKA can enhance the firms’ absorp- tive capacity. 5. Future Research Like all empirical research, this study has some limita- tions that should be addressed in future research. One caution is that the results of the current study are the context of software offshore outsourcing cooperation. Although we believe that it is theoretically feasible to extend this study to other contexts, the specific differ- ences between China an d other transition economy coun- tries restrict the adaptive capacity of our findings. Therefore, the other useful extension would be to con- duct this study in other transitional environments. More- over, the cross-sectional data used in the study do not allow for causal interpretation among the factors, al- though we requested that the sample firms supply data during the previous five-year period. Then, longitudinal approach will be needed in future studies. REFERENCES [1] Y. Caloghirou, I. Kastelli and A. Tsakanikss, “Internal Capabilities and External Knowledge Sources: Comple- ments or Substitutes for Innovative Performance,” Tech- novation, Vol. 24, No. 1, January 2004, pp. 29-39. doi:10.1016/S0166-4972(02)00051-2 [2] B. Hillebrand and W. G. Biemans, “The Relationship between Internal and External Cooperation: Literature Review and Propositions,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 17, No. 4, April 2003, pp. 735-743. doi:10.1016/S0148-2963(01)00258-2 [3] W. M. Cohen and D. A. Levinthal, “Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation,” Admin- istrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 35, No. 1, January1990, pp. 128-152. doi:10.2307/2393553 [4] P. J. Lane, J. E. Slak and M. A. Lyles, “Absorptive Ca- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. iB  The Effect of Knowledge Management on Product Innovation - Evidence from the Chinese Software Outsourcing Vendors 22 pacity, Learning, and Performance in International Joint Ventures,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 22, No. 12, December 2001, pp. 1139-1161. doi:10.1002/smj.206 [5] S. A. Zahra and G. George, “Absorptive Capacity: A Review, Reconceptualization, and Extension,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 27, No. 2, February 2002, pp. 185-203. doi:10.2307/4134351 [6] P. J. Lane and B. R. Koka, “The Reification of Absorp- tive Capacity: A Critical Review and Rejuvenation of the Construct,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 31, No. 4, April 2006, pp. 833-863. [7] K. M. Eisenhardt and J. Martin, “Dynamic Capabilities: What Are They,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 21, No. 10-11, October 2000, pp. 1105-1121. doi:10.1002/1097-0266(200010/11)21:10/11<1105::AID- SMJ133>3.0.CO;2-E [8] C. Lee, K. Lee and J. M. Pennings, “Internal Capabilities, External Networks, and Performance: A Study on Tech- nology-Based Ventures,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 22, No. 6-7, June 2001, pp. 615-640. doi:10.1002/smj.181 [9] R. M. Grant, “Prospering in Dynamically Competitive Environments: Organizational Capability as Knowledge Integration,” Organization Science, Vol. 7, No. 4, April 1996, pp. 375-387. doi:10.1287/orsc.7.4.375 [10] K. L. Turner and M. V. Makhija, “The Role of Organiza- tional Controls in Management Knowledge,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 31, No. 1, January 2006, pp. 198-217. [11] Nonaka, “A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowl- edge Creation,” Organization Science, Vol. 5, No. 1, January 1994, pp. 14-37. doi:10.1287/orsc.5.1.14 [12] D. J. Teece, G. Pisano and A. Shuen, “Dynamic Capabili- ties and Strategic Management,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 18, No. 7, July 1997, pp. 509-533. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7<509::AID-S MJ882>3.0.CO;2-Z [13] C. J. Chen and J. W. Huang, “How Organizational Cli- mate and Structure Affect Knowledge Management - the Social Interaction Perspective,” International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 27, No. 2, February 2007, pp. 104-118. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2006.11.001 [14] M. A. Lyles and J. E. Salk, “Knowledge Acquisition from Foreign Parents in International Joint Ventures,” Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 27, No. 5, May 1996, pp. 877-903. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490155 [15] M. Song, V. B. Hans and M. Weggeman, “Determinants of the Level of Knowledge Application: A Knowl- edge-Based and Information-Processing Perspective,” Journal of Product Innovation Management, Vol. 22, No. 5, May 2005, pp. 430-444. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5885.2005.00139.x [16] E. Danneels and E. J. Kleinschmidt, “Product Innova- tiveness from the Firm’s Perspective: Its Dimensions and Their Relation with Project Selection and Performance,” Journal of Product Innovation Management, Vol. 18, No. 6, June 2001, pp. 357-373. doi:10.1016/S0737-6782(01)00109-6 [17] L. J. Cronbach, “Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Struc- ture of Tests,” Psychometrika, Vol. 16, No. 3, March 1951, pp. 297-334. doi:10.1007/BF02310555 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. iB

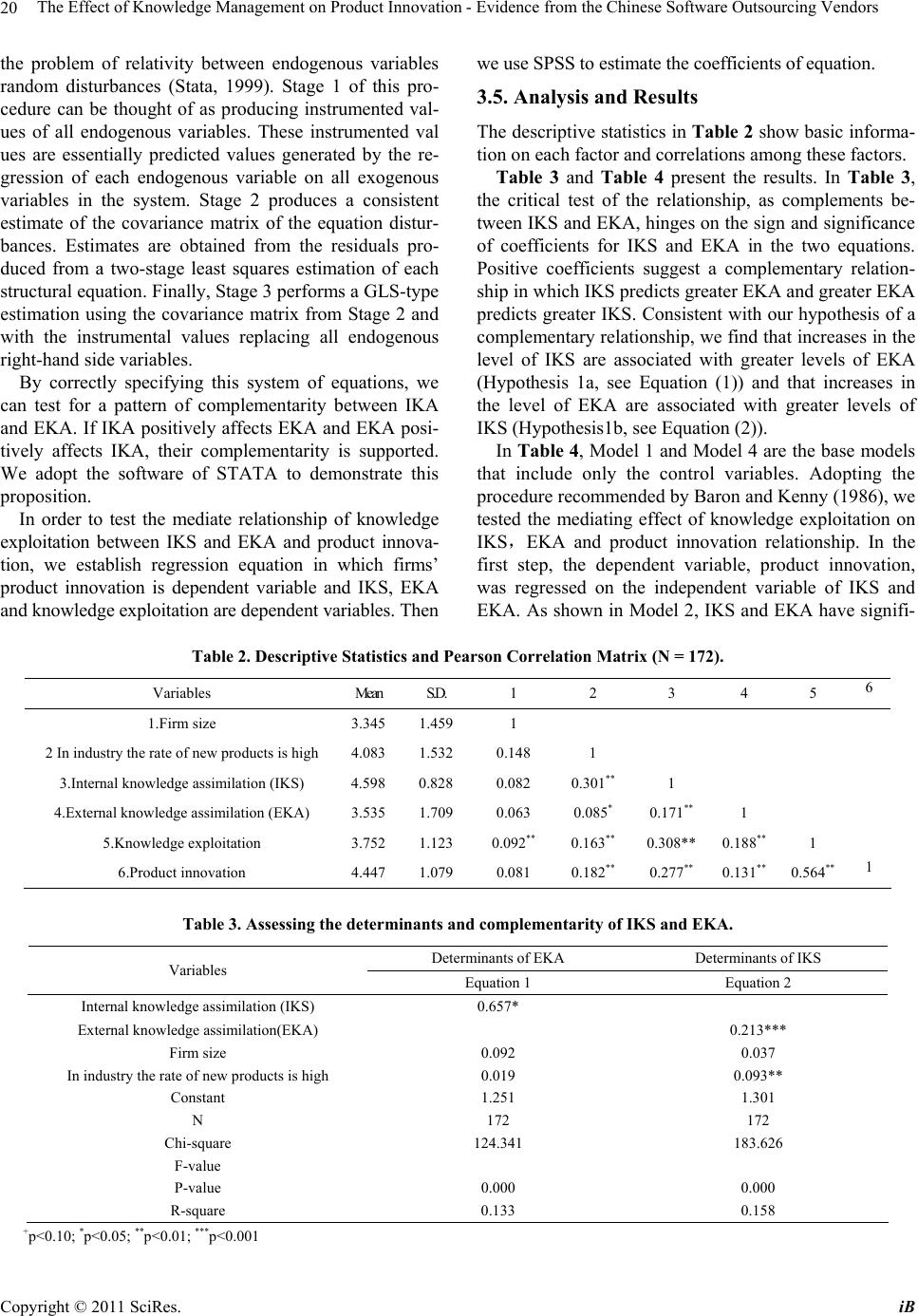

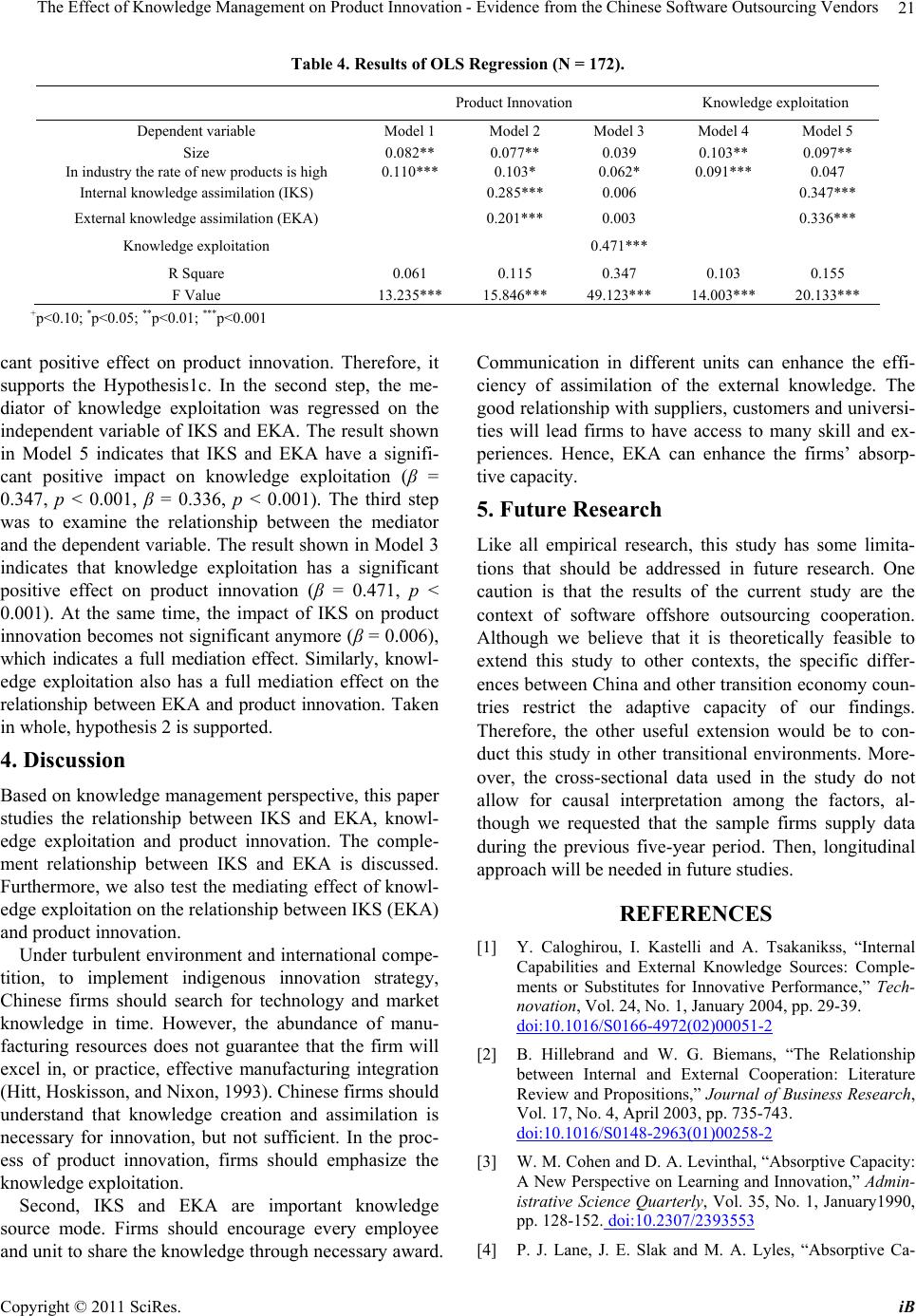

|