Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

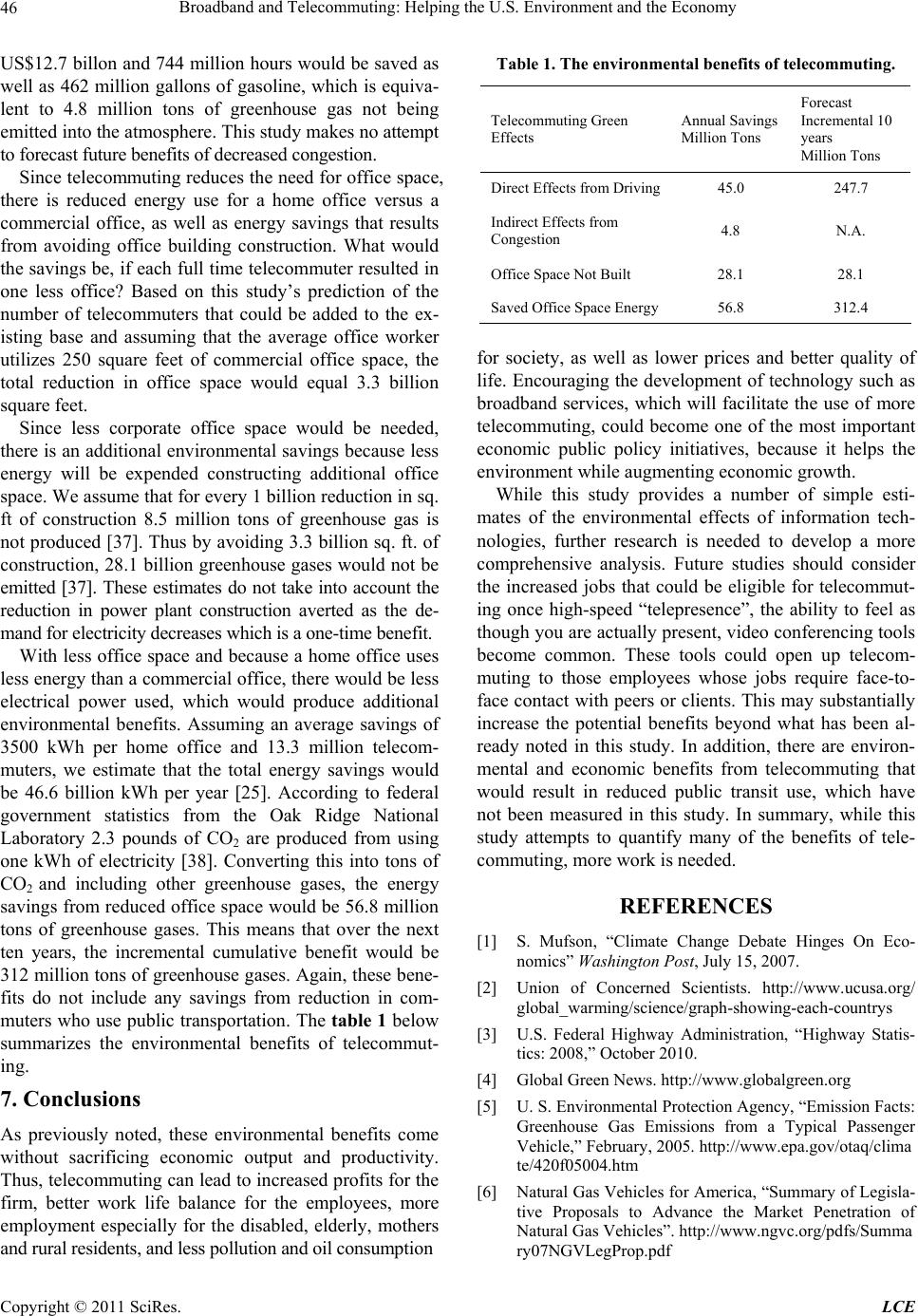

Low Carbon Economy, 2011, 2, 41-47 doi:10.4236/lce.2011.21007 Published Online March 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/lce) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. LCE 41 Broadband and Telecommuting: Helping the U.S. Environment and the Economy Joseph P. Fuhr1,2, Stephen Pociask2 1Economics Widener University Chester, PA, USA; 2The American Consumer Institute, Washington, D.C., USA. Email: jpfuhr@widener.edu Received December 3rd, 2010; revised December 20th, 2010; accepted December 29th, 2010. ABSTRACT This study examines how to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. through the widesp read delivery of broad band services and the expansion of telecommuting. Telecommuting can reduce greenhouse gas emissions over the next 10 years by approximately 588.2 tons of which 247.7 million tons is due to less driving, 28.1 million tons is due to redu ced office construction, and 312.4 million tons because of less energy usage by businesses. This paper explores these broadband services and their effects on the environment, specifically as a means to achieve better and cleaner energy use, while enhancing economic output, worker productivity and the standard of living of American consumers. Keywords: Broadband, Economy, Environment, Telecommuting 1. Introduction The world is becoming more and more aware of and concerned about changes in the atmosphere due to ex- treme weather events, melting glaciers, and changing ecosystems. As the Washington Post noted in a special report about global warming and climate change, “broad scientific evidence suggests that carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions have already triggered changes in the Earth’s climate and that more disruptive changes lie ahead” [1]. The story discussed a range of costly and daunting measures to address the problem by reducing emissions. This paper adds to the discussion of how to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by documenting the reductions that can be realized by the widespread delivery of broadband services in the U.S. Current carbon dioxide emissions in the U.S. hover around 5.8 billion tons and are growing [2]. In this study we examine only one as- pect of broadband’s ability to d ecrease carbon emissions, that of telecommuting. Broadband can not only decrease pollution but also contribute to economic growth and job creation. 2. Present Situation In 2008, there wer e 256 million motor veh icles register ed in the U.S., with automobiles and trucks accounting for 54% and 39% of these vehicles, respectively [3]. By one source, the use of personal vehicles accounts for 30% to 50% of greenhouse gas emissions, as well as similar ef- fects on toxic water and air pollutants [4]. The typical personal vehicle produces 5.0 tons of carbon dioxide annually [5], as well as methane, nitrous oxide and vari- ous man-made gases. The roads needed to move vehicles are also a threat to the environment, as they replace for- ests and affect animal habitats. These roads are usually constructed with petroleum components, their mainte- nance expends energy and resources, and they produce hazardous runoff into nearby streams. A number of legislative proposals have called for re- quiring more energy efficient automobiles and encour- aging the productio n of alternative fu els [6 ,7]. While pro- viding benefits, however, these proposals are likely to produce more expensive automobiles and significantly higher fuel costs. The most popular alternative fuel, ethanol, is typically produced from corn and is more ex- pensive than gasoline. Since corn prices have increased faster than other goods and services, the outlook for etha- nol as an alternative source of energy will mean that co rn prices are likely to continue to increase faster than the price of other goods and services. Since corn is used as feedstock, as well as for cereals and other foods, higher prices will mean higher food prices for consumers, in addition to higher energ y prices [8]. Moreover, the use of many of these alternative fuels, like ethanol and other bio-based energies, still result in carbon emissions. One  Broadband and Telec o m mu t i n g : Help i ng the U.S. Environment and the Economy 42 advantage is that domestically-produced ethanol re- lieves some pressure on oil-imports. Alternate fuels still leave policymakers with difficult choices that pose high costs for consumers, at least in the short run, but the cost of oil is likely to rise as reserves are depleted. 3. Telecommuting and Telework Broadband services help provide seamless data, video and voice communications, permitting workers to use their home in the same manner as a businesses’ office in what is described as telecommuting and telework. Tele- commuting is the use of telecommunications technology to allow employees to work from their homes and avoid the use of transportation to commute to and from work [9]. Telework is the use of telecommunications to work anywhere other than the home office, such as telework sites satellite offices, and remote locations [10]. Another group not covered by eith er term is home-based workers, who consist of self -e mployed w orker s who w ork at home instead of renting office space. Of the 25.4 million firms in the U.S., nearly 20 million (77%) are non-employer firms [11]. Of these, nearly 85% are in service industries, many of which are very conducive to home-based work- ing arrangements [11]. However, the amount of tele- commuting in the U.S. is constrained by the fact that only about one-half of U.S. households have a high- speed connection to the Internet [12]. These statistics suggest that there is potential for growth in telecommut- ing. Based on data thro ugh early 2006, only 2% of wor kers telecommute full time and 8% operate businesses from home, suggesting that 10% regularly work at home [13]. However, 25% had the potential to regularly work from home [13]. Similarly, a survey by Dieringer Research found 14.7 million individuals working almost every day from home during 2006 [14]. Given that there are 146 million persons employed in the U.S [15], the percent of full time home workers is (again) about 10%. However, 28.7% of workers work at least one day per month from home, and 44.8% report having done some work from home [14]. Therefore, the potential for expanding tele- commuting could be significant, providing that workers and employers see the benefits of working remotely from the office. In addition, the potential for increased telecommuting for government workers is high. According to the Office of Personal Management 41% of federal workers are eligible for telecommuting but only 19% do [16], which constitutes 7.7% of total federal workforce [16 ]. Senators Landrieu (D-La.) and Stevens (R-Ak.) have introduced a bill that will make more federal government employees eligible for telecommutin g [16]. 4. Potential Benefi ts of Telecommuting Balaker adeptly describes telecommuting as “the most cost-effective way to reduce rush-hour traffic and it can improve how a weary nation copes with disasters, from hurricanes to terrorist attacks” [17]. He states: It helps improve air quality, highway safety, and even health care as new technologies allow top-notch physi- cians to be (virtually) anywhere. Telecommuting expands opportunities for th e handicap ped, conserves energy, and – when used as a substitute for offshore outsourcing – it can help allay globalization fears and save American jobs. It can even make companies more profitable, which is good news for our nation’s managers, many of whom have long been suspicious of telecommuting [17]. The major gain to the environment from telecommut- ing is the decrease in the number of automobile trips. A recent survey found that 91% of workers commute by car, 4% by ride sharing, 3% by public transit and 3% by other means [13]. Telecommuting is zero emission transporta- tion. Studies show that telecommuters reduce daily trips on days that they telecommute by up to 51% and auto- mobile travel by up to 77% [17]. Since people are staying home instead of driving to work, telecommuting reduces fuel consumption and im- proves air quality. There is less traffic congestion, oil consumption, and noise and air pollution as a result of telecommuting. Since fewer cars are needed, telecom- muting will also save emissions and pollution associated with automobile production. With fewer cars needed for commuting, car production can be reduced. Another benefit is that less infrastructure will be needed, avoiding construction and road maintenance costs, as well as re- ducing hazardou s runoff into nearby streams. On the other hand, those who telecommute may not save the entire trip-miles to and from work. They may still use their car to drop off a child at daycare or pick up groceries, as they formerly did on route to and from an office. They may move further from an urban area to take advantage of a rural setting, increasing the commute dis- tance when they actually go to an office. These offsets have been referred to as the “rebound effect” and more study is needed to determine how they impact the overall savings which telecommuting can potentially deliver. 5. Stakeholders that Benefit from Telecommuting Who benefits from telecommuting? In general, telecom- muting can benefit various stakeholders such as consum- ers, employees, employers and society especially the elderly and disabled. 5.1. Benefits to Employees Employees can benefit in various ways from telecom- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. LCE  Broadband and Telec o m mu t i n g : Help i ng the U.S. Environment and the Economy43 muting. Telecommuting can provide job flexibility, which can improve the balance between work and personal time. Telecommuters have increased job satisfaction, a distrac- tion free environment, better time management, are less involved in office politics and generally have less stress. Pitney Bowes offers telecommuting “to enhance employee effectiveness and positively impact the quality of life of workers by minimizing the stress, fatigue, time and cost associated with commuting to and from work” [18]. Also, by eliminating the commute to work people have more time for work or leisure. According to US Depart- ment of Census data, the average commute is 26.4 min- utes each way or 53 minutes daily [19]. Telecommuting allows workers to find more time savings by reorganiz- ing their lives to take advantage of many different kinds of low congestion periods. Those who shop during off- peak find parking easier and they also spend less time at the checkout line [17]. Quality of life increases as they workout in a less crowded health club which saves time. During break s from work, they can do household cho res. They can take their children to and from school, and be home when the children leave or arrive. There is also gas savings as well as lower mainten ance costs as usage of the vehicle decreases. By one estimate, the typical worker pays US$688 annually for work-re- lated gasoline, and represents a direct savings for tele- commuters [13,19]. This decrease in usage from tele- commuting means that fewer cars are needed. Telecom- muters save money by eating out less, decreasing daycare needs, and spending less on work-wardrobes and dry cleaning. There is also the potential for a tax deduction for a home office. 5.2. Benefits to Employers Employers have also gained from telecommuting. There are various estimates of the gain in productivity as a re- sult of telecommuting. Allenby reports that Siemens, Compaq, Cisco, Merrill Lynch, Nortel and American Express have reported increases in productivity as a re- sult of telework programs of between 10% and 50%, and a five-year Smart Valley study found an average of 25% increase in productivity for participating companies [20]. Another advantage is that performance is measured by results rather than hours in the office. While absenteeism increases when employees are sick or have a sick child, telecommuting may allow the worker to be somewhat productive. Also if an employee has a contagious illn ess, telecommuting will reduce the spread of illnesses to other workers, thereby increasing productivity. Thus both absenteeism and presenteeism decreases. It is estimated that presenteeism costs US companies about US$150 billion a year [17] and that the increased flexibility in scheduling as a result of telework saves companies around US$2 000 per teleworker annually in reduced absenteeism [20]. Bad weather and emergencies, like terrorism, fires or natural disasters, are less likely to affect employees’ abil- ity to get to work. For example, JetBlue uses at-home agents for its reservation center which greatly increases the flexibility of the firm, as well as reducing the cost of booking a flight by 20% [20]. A company spokesperson stated: When things get busy, like during a weather event, we can send an e-mail to all agents asking them to log in to help. The response is immediate – we don’t have to wait for them to come in [21]. Studies have shown that telecommuting decreases the turnover rate which can significantly de crease the cost of training and recruiting. Best Buy has instituted a program for telecommuters called ROWE. This program has a 3.2% lower voluntary turnover rate than non-ROWE teams. Best Buy has estimated the per-employee cost of turnover is US$102 000 and productivity is 35% higher for ROWE team members [22]. Also employees are more loyal, focused and energized. Telecommuting allows employees who otherwise would not be able to commute such as mothers, the elderly and the disabled the oppor- tunity to be gainfully employed. Since telecommuting increases the pool of applicants and thus the quality of employees it can give a firm a competitive advantage by being the employer of choice. A senior Director at Sun Microsystems states “We found that our remote employ- ees were among our most excellent performers” [23]. As a result of telecommuting, firms will need less equipment, office space, parking spaces, office equip- ment, supplies and other amenities. IBM claims it saves almost US$1 billion a year in avoided real estate costs, thanks to telecommuting [20]. Sun Microsystems esti- mated that it saved US$69 million in real estate cost in 2005, as a result of its telecommuting program [23], and it was able to decrease office space use by 30% after im- plementing its “iWork” program [24]. Nortel and AT&T estimate telecommuting saves US$20 million and US$25 million in real-estate costs, respectively, while Unisys cut office space 90% [17]. In one study, AT&T found that employee productivity improved by US$65 million, in- creased labor retention saved US$15 million [20], and teleworkers avoided commuting 100 million miles, which reduced carbon dioxide emissions by 45 000 tons less of CO2 emissions, or around 1.8 tons per teleworker [20 ]. In that study, broadband access to the Internet was found to be a critical success factor [20]. Studies also found en- ergy savings because construction was avoided and be- cause the energy required in a home office was substan- tially less than in a commercial office. For instance, one study found a reduction in energy use and a savings in Copyright © 2011 SciRes. LCE  Broadband and Telec o m mu t i n g : Help i ng the U.S. Environment and the Economy 44 real estate costs of US$25 million [20]. Another estimate found that home offices use less energy than a commer- cial office – a difference between 3 000 to 4 400 kWh per year [25]. Romm estimated that 3.5 billion square feet of saved commercial space would result in the avoidance of 35 million metric tons of greenhouse gases [25]. Also, the avoidance of construction of these build- ings would save another 36.4 million metric tons of greenhouse pol lut i on [ 25]. 5.3. Other Benefits to Society Besides the environmental benefits of telecommuting, there are various other benefits to society. With less commuting, the number of automobile accidents and deaths will decrease as well as maintenance and infra- structure cost for roads, there will be less of a strain on public transit. There are also ben efits to rural economies, since people can live where they work. Workers can also supplement their earnings by using technology to earn money by working at home as a second job. Decreasing the amount of pollution will also decrease health-related problems especially respiratory ailments which are exac- erbated by particulate pollution. Two groups that find it particularly difficult to commute to work and could par- ticularly benefit from the ability to work from home are the disabled and elderly. The ability to telecommute could result in increased opportunities for gainful em- ployment. Also, telecommuting can lead to homeshoring which “is the transfer of service industry employment from offices to home-based employees with appropriate telephone and Internet facilities” [26 ]. This will decrease the flight of jobs overseas. 5.3.1. Benefits to Elderly and Disabled Broadband can greatly increase the quality of life and potential job opportunities for the elderly and disabled. Litan found that broadband deployment and use lowered medical costs and institutionalized living, while increas- ing labor force participation for seniors and individuals with disabilities [27]. All told, Litan estimated the cumu- lative benefit to be at least US$927 billion over a 25-year period (with future benefits discounted in 2005 US$s) [27]. Litan states that “the broader use of the Internet, and specifically ‘broadband’ technologies, to deliver health care services and information to senior citizens and indi- viduals with disabilities, and to make it easier for mem- bers of both populations to work, if they are willing to do so” [27]. Given that many elderly and disabled are un- able to travel to work, telecommuting offers expanded work opportunities. The potential for increased employ- ment is especially important to disabled Americans whose unemployment rate is 75% [17]. 5.3.2. Homeshoring Reports suggest that millions of jobs have been out- sourced to overseas companies, a phenomena referred to as offshoring. One report cites that half of the Fortune 500 companies have offshored jobs [28], and Forester Research predicts 3 million jobs will be moved overseas by 2015 [29,30]. Concerns over these lost domestic jobs have led to lawmakers crafting over 200 bills designed to impede offshoring [17]. The alternative, homeshoring, can be the domestic answer to this exodus, and broad- band technology can play an importan t role in this rever- sal. Homeshoring is the use of home-based agents to field various types of customer care inquirers. “Virtual” call centers employ home based agents which takes away the need for the brick-and-mortar. Early adopters of homeshoring include JetBlue Airways, Alpine Access, PHH Arval and LiveOps [21]. Homeshoring encourages a diverse workforce that could include mothers, retirees, students, and people with disabilities and people who want maximum flexibility [21]. Technology has the po- tential to change the landscape of customer care services. Growth in broadband services to the home, including voice-over-Internet telecommunications and softswitch technologies, has decreased labor and facility costs. One study estimated that in a traditional call center in the United States costs are around US$31 per employee hour, including overhead and training, whereas home based agents can decrease cost by up to US$10 an hour. Home- based retention rates are around 85%, whereas conven- tional call centers have a retention rate of between 10% and 20% [31]. The higher productivity and lower cost have made homeshoring a competitive alternative to off- shore outsourcing, which has had a negative impact on domestic employment opportunities. The presence of broadband infrastructure in rural communities can serve to develop a pool of online workers, which may attract information-based businesses, such as IT development, software and IT service businesses, as well as back-office telecommunications centers. By increasing broadband development and use, as well as encouraging telework participation, a pool of flexible workers can be drawn upon that can stem, and possibly reverse, the loss of do- mestic jobs. As worker productivity and morale increases, a firm’s per unit costs decrease. Given competitive markets, de- creases in per unit costs result in lower prices and in- creased quality for consumers. In addition, the quality of the customer service experience will improve, since do- mestic-based telecommuters can more easily and quickly be called upon to deal with peak periods of demand, thereby reducing long hold times in customer service call centers and help hotlines. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. LCE  Broadband and Telec o m mu t i n g : Help i ng the U.S. Environment and the Economy45 6. Estimation of Environmental Benefits of Telecommuting 6.1. Direct Benefits On an average work day, millions of Americans com- mute between home and work by way of their personal vehicle. According the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are 146 million persons employed in the U.S [15], and transportation statistics show that 91% of workers (or 132.9 million workers) use personal cars to commute to work [32]. Assuming that that the average number of people in a carpool is 3, approximately 127.5 million personal vehicles are regularly used to commute 132.9 million workers. This activity expends time, creates con- gestion, costs lives in car accidents, and it wastes motor vehicles, maintenance, fuel and public resources. The average U.S. worker commutes 15 miles and 26.4 minutes one-way to th eir job [19], which means that 918 billion miles are traveled and 1.7 trillio n minutes are lost in the course of a 240 day commuting year. To put this into context, the travel time wasted is equivalent to the annual paid hours of 17.2 million production workers. The lost wages and cost of the vehicle (including gas, depreciation, insurance and maintenance) would be nearly US$1 trillion or, incredibly, 7.2% of the total gross do- mestic product of the U.S. In other words, for every US$14 produced in the economy; US$1 is wasted just getting employees to work using their personal vehicle. The effect on the environment is equally stunning. Assuming fuel efficiency of 21 miles per gallon, com- muting to work using personal vehicles consumes 44 billion gallons of gasoline per year. In terms of green- house gasses, private vehicles used during commuting release 424 million tons of carbon dioxide into the at- mosphere each year [33]. In addition, other emissions include 23 million tons of carbon monoxide, 1.8 million tons of volatile organic carbons and 1.5 million tons of oxides of nitrogen each year [34]. All of these statistics ignore the fuel expended for public transportation, gov- ernment vehicles and other vehicles, most notably those used for construction, material transportation, shipping and commercial sales fleets. As the literature presented in this study shows, tele- commuting can redu ce pollutants withou t sacrificing, and likely augmenting, economic productivity. As previously noted, around 10% of workers telecommute full time, approximately one-tenth of these economic and envi- ronmental costs are already being saved, which approxi- mates an annual reduction of 45 million tons of green- house gases. According to a survey conducted by Rockbridge the potential for telecommuting could reach 25% participa- tion. One holdback on telecommutin g is th e fact that only half of U.S. households have broadband services, which suggests (again) that telecommuting could well double in the U.S [12]. Using the economic and environmental costs discussed earlier in this paper, a doubling of the current level of telecommuting, to say 20%, would mean that one-fifth of the environmental cost of commuting could be elim inat ed. To highlight the future (potential) benefit of telecom- muting, this study estimates the effect of an increase in telecommuting equal to an additional 10% of the work- force over the next ten years. Based on this incremental increase and using the same calculations as before, the total economic savings direct time and expense would be US$96.5 billion, including the cost of 4.4 billion gallons of gasoline each year. In terms of the environmental benefits, if 10% more of the workforce could telecom- mute fulltime, emissions of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere would be reduced by an additional 42.4 mil- lion tons of carbon dioxide, as well as 2.6 million tons of other pollutants, which results in 45.0 million fewer tons of greenhouse gases each year. Over the next ten years, the cumulative incremental savings would be equal to 247.7 million tons of greenhouse gases. Keep in mind that these benefits include only those associated with the use of a personal car, and not wi t h pu bl i c tra nsp o rt at i on. 6.2. Indirect Benefits While these are potential direct benefits, there are many indirect benefits, some of which can be approximated, such as the benefits from reduced traffic. While there are benefits to drivers who telecommute, the reduction in traffic bestows a benefit on all other drivers. In other words, as road congestion is reduced, there are benefits for those who continue to use the roads, and these bene- fits could be significant. In 2003, according to the Texas Transportation Institute, US$63.1 billion worth of time and fuel was wasted due to traffic congestion during rush hour in 85 metropolitan areas. This resulted in 3.7 billion hours per year, which is an average of 47 hours per commuter and 2.3 billion gallons of gas [35]. As previ- ously estimated there are 127.5 million work commuter vehicles. According to 2000 U.S. Census of those com- muters, 66.9 million or 52.5 percent leave for work be- tween 6:30 and 8:29 in the morning which will be con- sidered peak time. John Edwards, chairman and founder of the Telework Coalition notes that “for every 1% re- duction in the number of cars on the road there is a 3% reduction in traffic cong estion” [36]. If the average num- ber of vehicles on the road during rush is 100 million, a 10% increase in telecommuting would result in 6.7 (6.7%) million less private vehicles commuting to work during rush hour, or 20.1% decrease in congestion. In this sce- nario, the savings in wasted time and fuel would be Copyright © 2011 SciRes. LCE  Broadband and Telec o m mu t i n g : Help i ng the U.S. Environment and the Economy 46 US$12.7 billon and 744 million hours would be sav ed as well as 462 million gallons of gasoline, which is equiva- lent to 4.8 million tons of greenhouse gas not being emitted into the atmosphere. This study makes no attempt to forecast future benefits of decreased congestion. Since telecommuting reduces the need for office space, there is reduced energy use for a home office versus a commercial office, as well as energy savings that results from avoiding office building construction. What would the savings be, if each fu ll time telecommuter resulted in one less office? Based on this study’s prediction of the number of telecommuters that could be added to the ex- isting base and assuming that the average office worker utilizes 250 square feet of commercial office space, the total reduction in office space would equal 3.3 billion square feet. Since less corporate office space would be needed, there is an additional env ironmental savings because less energy will be expended constructing additional office space. We assume that for every 1 billion reduction in sq. ft of construction 8.5 million tons of greenhouse gas is not produced [37]. Thus by avoiding 3 .3 billion sq. ft. of construction, 28.1 b illion greenhouse gases would not be emitted [37]. These estimates do not take into account the reduction in power plant construction averted as the de- mand for electricity decreases which i s a one-time benefit . With less office space and because a home office uses less energy than a commercial office, there would be less electrical power used, which would produce additional environmental benefits. Assuming an average savings of 3500 kWh per home office and 13.3 million telecom- muters, we estimate that the total energy savings would be 46.6 billion kWh per year [25]. According to federal government statistics from the Oak Ridge National Laboratory 2.3 pounds of CO2 are produced from using one kWh of electricity [38]. Converting this into tons of CO2 and including other greenhouse gases, the energy savings from reduced office space would be 56.8 million tons of greenhouse gases. This means that over the next ten years, the incremental cumulative benefit would be 312 million tons of greenhouse gases. Ag ain, these bene- fits do not include any savings from reduction in com- muters who use public transportation . The table 1 below summarizes the environmental benefits of telecommut- ing. 7. Conclusions As previously noted, these environmental benefits come without sacrificing economic output and productivity. Thus, telecommuting can lead to increased profits for the firm, better work life balance for the employees, more employment especially for the disabled, elderly, mothers and rural residents, and less poll ution and oil consum ption Table 1. The environmental benefits of telecommuting. Telecommuting Green Effects Annual Savings Million Tons Forecast Incremental 10 years Million Tons Direct Effects from Driving45.0 247.7 Indirect Effects from Congestion 4.8 N.A. Office Space Not Built 28.1 28.1 Saved Office Space Energy56.8 312.4 for society, as well as lower prices and better quality of life. Encouragin g the development of technology su ch as broadband services, which will facilitate the use of more telecommuting, could become one of the most important economic public policy initiatives, because it helps the environment while augmenting economic growth. While this study provides a number of simple esti- mates of the environmental effects of information tech- nologies, further research is needed to develop a more comprehensive analysis. Future studies should consider the increased jobs that could be eligible for telecommut- ing once high-speed “telepresence”, the ability to feel as though you are actu ally present, video con ferencing tools become common. These tools could open up telecom- muting to those employees whose jobs require face-to- face contact with peers or clients. This may substantially increase the potential benefits beyond what has been al- ready noted in this study. In addition, there are environ- mental and economic benefits from telecommuting that would result in reduced public transit use, which have not been measured in this study. In summary, while this study attempts to quantify many of the benefits of tele- commuting, more work is needed. REFERENCES [1] S. Mufson, “Climate Change Debate Hinges On Eco- nomics” Washington Post, July 15, 2007. [2] Union of Concerned Scientists. http://www.ucusa.org/ global_warming/science/graph-showing-each-countrys [3] U.S. Federal Highway Administration, “Highway Statis- tics: 2008,” October 2010. [4] Global Green News. http://www.globalgreen.org [5] U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Emission Facts: Greenhouse Gas Emissions from a Typical Passenger Vehicle,” February, 2005. http://www.epa.gov/otaq/clima te/420f05004.htm [6] Natural Gas Vehicles for America, “Summary of Legisla- tive Proposals to Advance the Market Penetration of Natural Gas Vehicles”. http://www.ngvc.org/pdfs/Summa ry07NGVLegProp.pdf Copyright © 2011 SciRes. LCE  Broadband and Telec o m mu t i n g : Help i ng the U.S. Environment and the Economy Copyright © 2011 SciRes. LCE 47 [7] B. Yacobuuci, “Alternative Fuels and Advanced Tech- nology Vehicles: Issues in Congress,” Congressional Re- search Service, September 22, 2010. http://www.fas.org/ sgp/crs/misc/R40168.pdf [8] R. R. Cooke, “What is the real Cost of Corn Ethanol?” Financial Sense Editorials, February 2, 2007. http:// www.financialsensearchive.com/editorials/cooke/2007/02 02.html [9] W. Leonhard, “The Underground Guide to Telecommut- ing,” Addison-Wesley, 1995. [10] J. M. Nilles, “Managing Telework: Options for Managing the Virtual Workforce,” John Wiley & Sons, 1998. [11] U.S. Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy, data provided by the U.S. Census Bureau, “Nonemployer Statistics”. www.sba.gov [12] Park Associates, “U.S. Residential Broadband Penetration to Exceed 50% in 2007,” 2007. http://www.parksassociat es.com/press/press_releases/2007/dig_lifestyles1.htmlat [13] Rockbridge Associates, “U.S. Workers Waste $3.9 Bil- lion Annually by Not Telecommuting,” July 2006. www. rockresearch.com/news_071206.php [14] Dieringer Research Group, “Telework Trendlines for 2006,” commissioned by WorldatWork, February 2009. [15] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, http://www.bls.gov/ news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf [16] S. Barr, “Senators Push for More Telecommuting,” Wa- shington Post, March 30, 2007. [17] T. Balaker, “T he Quiet Success: Telecommut ing’s Impact on Transportation and Beyond,” Reason Foundation, Los Angeles, November 2005. [18] Pitney Bowes, “Commute Options Programs,” http:// www.bestworkplaces.org/pdf/awlp/commute_opts.pdf [19] U. S. Department of Transportation, Bureau of Transpor- tation Statistics, “From Home to Work, the Average Commute is 26.4 Minutes,” Vol. 3/4, October 2004. http://www.bts.gov/publications/omnistats/volume_03_is sue_04/html/entire.html [20] B. Allenby and J. Roitz, “Implementing the Knowledge Economy: The Theory and Practice of Telework,” Batten Institute Working Paper, 2003. [21] M. Frase-Blunt, “Call Centers Come Home,” HR Maga- zine, January 2007. [22] P. J. Kriger, “Flexibility to the Fullest,” Workforce Man- agement, September 25, 2006. [23] J. T. Arnold, “Making the Leap,” HR Magazine, May 2006. [24] R. D. Atkinson and A. S. McKay, “Digital Propensity: Understanding the Economic Benefits of the Information Technology Revolution,” The Information & Technology Foundation, Washington D.C., March 2007. [25] J. Romm, “The Internet and the New Energy Economy,” Center for Energy and Climate Solutions, Global Envi- ronment and Technology Foundation, 2002. [26] Macmillan English Dictionary. http://www.macmillandict ionary.com/new-words/050530-homeshoring.htm [27] R. E. Litan, “Great Expectations: Potential Economic Benefits to the Nation from Accelerated Broadband De- ployment to Older Americans and Americans with Dis- abilities,” New Millennium Research Council, December 2005. [28] B. Moyers, “The Outsourcing Debate,” Various Reports, Public Broadcasting Service. www.pbs.org/now/politics/o utsourcedebate.html and www.pbs.org/now/politics/ out- source.html [29] C. Ansberry, “Outsourcing Abroad Draws Debate at Home,” Wall Street Journal, July 14, 2003. [30] J. C. McCarthy, “3 Million US Services Jobs to Go Off- shore,” Forester Research Brief, November 11, 2002. www.forrester.com/ER/Research/Brief/Excerpt/0,1317,15 900,00.html [31] S. Loynd, “VIPdesk Helps Chart the Future: Homeshor ing Brand Ambassadors and the Shifting of the Customer Management Landsca p e , ” IDC, 2006. [32] U. S. Department of Transportation, Bureau of Transpor- tation Statistics, “National Household Travel Survey: Daily Travel Quick Facts”. www.bts.gov/programs/na- tional_household_travel_survey/daily_travel.html [33] U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Green Power Equivalency Calculator Methodologies”. http://www. epa.gov/greenpower/pubs/calcmeth.htm#vehicles [34] Telework Coalition’s Teletrips Emissions Calculator. http://www.telcoa.org/id134.htm [35] T. Lomax and D.Schrank, “2005 Annual Urban Mobility Report,” Texas Tr an sp ortation Instit ut e, 2006. [36] U. S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, “It all adds up to cleaner air,” Quarterly Newsletter, Winter 2006. http://www.italladdsup.gov/ newsletter/winter06/experts.html [37] Boston Consulting Group, “Paper and the Electronic Me- dia,” September 1999. [38] Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, “Frequently Asked Global Changes Questions”. http:// cdiac.ornl.gov/pns/faq.html |