Sociology Mind 2014. Vo l.4, No.1, 45-50 Published Online January 2014 in SciRes (h ttp://www.scirp.org/journal/sm) http://d x.doi.org/10.4236/sm.201 4.41006 Economic and Cultural Peripheralization in the Eurozone Antonio Luigi Paolilli University of Salento, Lecce, Italy Email: apaolilli@alice.it Received S eptember 5th, 2013; revised October 11th, 2013; accepted November 22nd, 2013 Copyright © 2014 Antonio Luigi Paolilli. Th is i s an open access arti c le distri bu ted und er the C reati ve Comm ons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 a re reserved for SC IRP and the owner of the int ellect ual p ropert y Antonio Luigi Paolilli. All Copyri ght © 2014 are guarded b y law and by SCIRP as a guardian. In this paper, we will discus s the reasona bleness of the decision b y It aly and other southern an d western EU sta t es t o bec ome me mber s of t he euroz one. We wi l l a l so di s cuss whether thi s economic choice can be socially and culturally sustainable in a Europe characterized by cultures which, despite their shared sub- stratum, are in competi tion with each other. Key words: Peripheralization; Social Cohesion; Economic History Introduction In 1992 when Italy left the EMS with a great devaluation, above all compared to the Deutsche mark1, it was not alone, because the pound sterling also withdrew from the EMS. The United Kingdom, however, did not join the eurozone, unlike Italy and other outlying states of the EU. In this paper, we will discuss the reasonableness of the decision by Italy and other southern and western EU members, in the light of the com- ments made in some recent papers. We will also examine the issue of whether this economic choice can be socially and cul- turally sustainable in a Europe characterized by cultu res which, despite their shared substratum, are in competition with each other. Restrictive Policies, Finance and Peripheralization Processes The years following the outbreak of the Global Financial Crisis have been characterized in most eurozone states, and above all in the so called PIIGS, by a great accel eration o f aus- terity policies consisting, besides further deregulation of the labor market, essentially of a reduction of public spending and in an increase in taxes, in order to achieve a balanced public budget. In the view of supporters of austerity, even though these fiscal policies were brought in during a crisis, and there- fore even though they cause a worsenin g of the recession, they should in the long term lead to a lasting economic recovery. This app roach has aroused radical criticism. It has been argued in fact that austerity policies not only herald recession, but they are also ineffective and even produce the opposite effect to the purpose of reducing the public debt/GDP ratio (Forges Davan- zati, 2 013 ; Cesaratto & Pivetti, 2012), due to the consequent re- cessive spiral which reduces the tax base. These criticisms, however, seem feeble to the advocates of austerity who, above all in the German area, believe that the differences among th e perfor mances o f the variou s EU me mber states are essentially caused by the different approaches taken by governments and even by the populations, which can be divided, in their opinion, into “cicadas” (spenders) and “ants” (savers). It has been shown, however (Paolilli, 2011a; Paolilli & Pol- lice, 2 011b ) that the p eripheralizatio n processes are mostl y due to geographical factors, stressing moreover the role that mone- tary and financial institutions have in territorial dynamics. Ac- cording to this viewpoint, the financialization of the economy, into the broader scenario of globalization, can reinforce cumu- lative processes which widen the pre-existing territorial gaps. Specifically, it has been shown, by means of a mathematical model, th at di sadvan taged regio ns can en d up financi ng, at least indirectly, the economic activities of those areas from which they have received direct investments. In fact, when a growth process begins in a region, it tends to extend to other areas, but the outcome of the investments in those areas is essentially dependent on some of their geographical and cultural characte- ristics. There are in fact various types of peripheral countries, which can be grouped essentially into two categories. The real peripheries (which we can call peripheries of type A), are usu- ally near the central areas (but not close enough to be progres- sively absorbed by them). They experience the economic and cultural influence of central areas, also due to workers’ emula- tive tendencies, but they could never reach the same levels of productivity and welfare (the comparison South-North of Italy is a good example of this scenario). In fact we can assu me that productivity is also a function of the worker’s effort. It must be consi dered that th e s maller the gap between the act ual wage and the target wage, the greater the effort, and that in the mind of workers of type A peripheries the target wage can be the same as that perceived by workers in central areas. Therefore, given the lower productivity of the peripheral regio ns (due to the fact that these areas are less interested by cumulative processes of economic growth), we can deduce that in type A peripheries 1Amato’s Government took the decision to get of EMS and to devalue the lira only after a strong, enduring and by then unsustainable attach of the market. OPEN ACCE SS 45 A. L. PAOLILLI there is a vicious circle: low productivity, low wages; little ef- fort, low productivity. In contrast, the peripher ies which are se- parated fro m the cen tral ar eas b y means o f p h ysical, po li tical or cultural barriers, and which we will call peripheries of type B, even though they may experience economic dependence, can easily overcome it if they have adequate physical and human resour ces. Besides showing the existence of a natural conflict between financers an d producers, in which finance seems to have a nat- ural aptitude to absorb industrial profits, the model in the work cited above also shows that interest rates in peripheral areas tend to be higher than in central areas. This phenomenon hind- ers the local enterprises which, at least in the initial phase of their growth, are small and therefore not able to easily obtain direct financing. The model, then, explains the prevalence of in- direct financial flows (i.e. carried out through banks) from pe- ripheral regions to central areas, flows which tend to counter- balance the diffusive effects of direct investments from central areas towards peripheral ones. The counterbalancing effect of indirect flows, moreover, is particularly deleterious for type A peripheries. These areas are often bypassed by direct funding, because the geographic and cultural proximity to central areas tends to raise t he target wages, re du cing effort and t herefore la- bor productivity, if real wages are significantly lower than tar- get wages. The vicious circle we have seen above is then rein- forced by th e finan cial d ynamics: t he differenc e b etween th e in - terest rate applied in central and peripheral areas, particularly type A (bu t also in type B, at least whil e they remain on th e pe- riphery), consolidate the processes of cumulative causation which increase t he difference i n produ ctivity between th e two types of regions. The theoretical considerations we have explained above are corroborated by what happens in the real world. As noted by Spratt (2009: p. 67), the liberalization started under Reagan’s presidency caused a much higher interest rate rise than ex- pected, above all in poor countries. Spratt also points out that, unexpectedly, i.e. contrary to the provisions of orthodox eco- nomic theory, many studies have shown that growth of real in- terest rates has often led to a fall in accumulation rates. Ex- amining the financial flows in the Nineties and early years of this millennium, first, the author observes that, again contrary to the forecasts by advocates of liberalization, they have not fol- lowed a linear trend, but cyclical behavior, with an alternation of growths and declines. Moreover, with the exclusion of direct financing, financial flows between developed countries and emerging areas have not only fluctuated, but have periodically changed direction too, resulting in a balance showing a net flow from developing regions to developed areas. Furthermore, we must stress that the financial flows studied by Spratt are those between developed regions and emerging areas, which can be classified as type B p eripheries. As we will al so see below, the dynamics are presumably even more pernicious for type A pe- riph er i es. Europe before the Integration: A Singular Case of Cooperation and Competition From the discussion above we can deduce that many prob- lems may derive by the increasing connectivity of the world, if not adequately regulated. As far as Europe is concerned, these problems are exacer- bated by the adoption of a single currency, which is not coun- terbalanced by the existence of a single state. National curren- cies, in fact, were a sort of barrier amongst the various econo- mies of the Union, without, however, greatly reducing their trade with each other. Trade was int ense but it was adjusted b y the rising and falling of national currencies. The resulting situa- tion, therefore, can be called an optimal combination of coop- eration and competition. The v iew that productivity can be higher if there is a balanc- ed combination of competition and cooperation is underlined by Diamond (2006, 1997: pp. 357, 360-361). It has been noted, for example, that technological progress, in modern industrial companies, is favored by a balanced mix of competition and circulation of information (which may be regarded as a form of cooperation). Big compani es which are hierarchically organized seem less efficient than others, equally large but composed of relativel y indepen dent units competing with each other, but not so much as to prevent information circulating among them. With regard to economic and political systems, it has been observed (Paolilli & Pol lice, 2011a), b y means of a mathemati - cal model, that the greater the competition and/or the less the cooperation and emulation, the lower the number of EPS (eco- nomic-pol iti cal systems) in a geograp h ical ar ea. The mod el als o shows th at technolo gical progress all ows an EPS to incr ease its area of influence, reducing the economic role of the EPS that are unab le to rapidly renew th eir tech nological level or to adop t strategies to diversify their production, specializing in the use of other resources. Since the Middle Ages Europe has been characterized by a singular combination of cooperation and competition. Coopera- tion was based on a common (Christian) culture, also favored by the use o f Latin by the ed ucated and the clergy, while co m- petition arose from the fact that it was difficult for societies whose economy was not based on sea trade as in Ancient Times (due to Islamic and other invasions in the Mediterranean basin), to unify in a single EPS. According to recent studies (Paolilli & Pollice, 2011a), this combination has probably been the main factor which allowed Europe, rather than other EP S, like China or the Roman empire, to undertake the development towards Modernity (see also Scheidel, 2007; Paolilli, 2008). It is inter- esting the make a comparison with China which, apart some short periods, was always more cohesive than Europe. It was precisely for this reason that, although 15th-century China was equipped with technologies which would allow it to undertake the development towards Modernity (its enormous fleet sailed and explored the Indian ocean), it only took a polit ical upheaval led by a few individuals at the top of the institutions to cause the total abandonment of expansionist policy and the isolation of that great nation (Diamond, 2006, 1997: p. 318). The mix of cooperation and competition, then, enabled Eu- rope to evolve towards Modernity because of the application of innovations was favored by the ease of disseminating ideas and at the same time it was necessitated by the fact that the conti- nental EPS were competing with each other. This, of course, does not necessarily mean that the optimal dimension for the European countries in the current global competition is still that of the single nation. We must consider, in fact, that increasing globalization, fa- vored by the speed of communications and the lowering of their costs, has changed the scale of competition from a regional or sub-continental context to a global one. In the present time, EPS the size of China do not risk being isolated. Their eco- nomic systems are in fact increasingly interconnected with the OPEN ACCE SS 46  A. L. PAOLILLI others and are therefore stimulated to a competition and coop- eration that are almost irreversible. With regard to Europe, the process of integration and coop- eration was increased by the establishment after the Second World War of an area of free trade, eliminating the possibility of wars, without however reducing that degree of competition which, t ogether with coop eration, as we have s een abo ve, is th e main factor of progress. The single stat es of the Euro pean Com- mon Market, in other words, cooperated more than in any other previous periods, but their single economic systems were mu- tuall y protected again st excessive co mpetiti on which cou ld lead to cent ralization and therefore perip heralization du e to monet a- ry barriers. The establ ishment of the E MS (March 13, 1979) had already reduced the amplitude of such barriers, further facilitating trade thanks to a careful control of exchange rates between EU cur- rencies. This control, however, ended up replacing a series of fluctuations in currency exchange rates, which could have re- gulated the trade relations between the countries, with one great final currency crisis which broke up the EMS2. The introduction of the Euro was not accompanied by the creation of a central government to implement a significant re- distribution of income. There continue to exist many states re- sponsible for administering public affairs without however be- ing able to issue currency while the monetary barriers between the EU Economic-Political Systems that adopted the euro have been demol ished , creating a kin d of “monopol y game” between the same economies. This has produced a concentration of fi- nancial resources, and therefore also of real resources, in the hands of a few and of the central areas of the Union. The phenomenon of concentration has not been stressed by the mainstr eam eco n omists, but it has been widely discussed by econo mic geograph ers, from the “cu mulat iv e causat io n” of My- rdal (1957) to the “New Economic Geography” of Krugman (1991, 1998). The tendency to concentration, moreover, has also bee n obs e r v e d in ot he r scientific cont ext s. Almost every branch of science i n fact recognizes the relev- ance of so-called “power law”, according to which it can be ob- served that in nature the most diverse phenomena, like the im- portance of rivers and stars, have a negative exponential rela- tionship with their size3. This phenomenon has been observed also in the concentration of wealth (in all the social and politi- cal contexts), where it takes the name of P areto distribut io n (see Mandelbrot, 1963), contradicting the opinions of those who think that market forces will naturally generate an optimal and eve n equi ta bl e dis t ri b ut ion of resources. Peripheries: The Cases of East Germany and South of Italy With regard to the differen ces b etween th e econo mic systems of Northern Europe and the Mediterranean European states, it has often been stressed that the latter need to comply with the former, in the belief that their failures deri ve above all from bad economic policies and bad habits, disinclined to austerity. We have been given, as an example to follow, the case of the unifi- cation of Germany, which would experience a rapid conver- gence between its East and West parts, following the reunifica- tion process which started in 1989. In actu al fact it is a rath er inter esting case b ecause, u nlike th e cases of P ortugal, Greece, I reland and Spain, it i s not related to a whole state, but to a part of it, and it is therefore more com- parabl e to the Italian situat ion, historically charact erized by the North-So uth gap. If we con sider, moreover, t hat East German y was annexed to West Germany and that it has suffered the po- litical and economic hegemony of the latter, the similarity with the case of Southern Italy is even stronger: East Germany, like Southern Italy, can be defined a type A periphery. The recent economic history of East Germany, however, is rather different from that of Southern Italy4. Unlike the latter, in fact, before the Second World War East Germany had one of the most advanced industrial systems in the world and its per capita GDP was higher than that of th e western part of Germa- ny. Moreover, besides being the seat of the political capital, East German y was l arger t han it i s n ow and was at th e cent re of important trade with the S lav countries. After the war, however, membership of the CMEA deteriorated the product competi- tiveness o f East Ger many and on re-ent ry into a market system, this caused such serious difficulties of adaptation that the sur- vival of man y businesses was threatened. To carr y out the rea- lignment process in East Germany, as in the Italian case, an “extraord in ary inter vent io n” was mad e. Ho wever, while i n I taly this intervention interested large-scale industry, in Germany it covered mainly small and medium-size enterprises. East Ger- many suffered a dramatic initial depression caused, in the opi- nion of many observers, by the decision to achieve economic union as quickly as possible and above all to impose an equal exchange rate between the Western and Eastern mark. The lat- ter, even though it was difficult to determine its actual value, given the great differences between the two economic and so- cial syste ms, was mu ch weak er than the former (Burker, 2009). Nevertheless the eastern regions have made great progress to- wards economic integration with West Germany. It should be noted, however, that since 2004, due to the ac- cession of several Eastern European states, East Germany, un- like southern Italy, is no longer a periph er al area, at least from a strictly geographic point of view (moreover, unlike Southern Italy, it is the seat of the country’s political center). In fact in recent years, perhaps as a result of the increased centrality of the area, a further convergence of per capita incomes of the “two Germanies” seems t o be underway. However, unlike most regions of southern Italy, almost all the regio ns of East Germany have exp erienced a signi ficant re- duction of population, both in relative terms (i f co mpared to th e rest of German y), and in absolute terms (see F i gures 1 and 2). East Ger many, in oth er words, h as not in creased its wealth sig- nificantly, but has rather divided it among fewer people. This phenomenon is illustrated, with regard to the demographic trends and for the period 1989-2004, by Figure 1. For the pe- riod 2004-2008 the thematic map of Figure 2 shows the rela- tive variations of population at level NUTS 2 (regional level). The graph in Figure 3 shows instead the changes in productiv- 2It has b een argued that in th e years following th e collapse of t he EMS, in spite of the devaluation of the Italian lira, there was a decrease in Italian sha r e of Europe an GDP and of European and world exports. This is not t rue if we consider per capita revenue and exports, i.e. if we take into account the reduction of the relative weight of the Italian population. Per capita ex- ports, for example, between 1992 and 2001 increased by 42% in Ita ly, while in France, Germany and the USA they increased, respectively, only by 34% 40% a n d 37% (Fa i ni , 2 00 3). It was the application of power law (Buchanan, 2008, pp. 183- 184) that allowed researchers to verify that t he furrows excavated on Mars are a c- tually relics of ancient basins and therefore on that planet there were once considerable quantities of watery liquid. 4About this topic see also C. Vita (2006-2007), pp. 87-92. OPEN ACCE SS 47  A. L. PAOLILLI ity in German y’s eastern regi on s, exp ressed in per cent age terms compared t o that of th e western regions. We can easily not e that productivity, after a fall following the unification, quickly reco- vered and progressively but more and more slowly approached the productivity of the western regions, without reaching it. Fi- gure 4 compares per capita income rate of the eastern regions with that of the western parts of Germany. It is interesting to examine, las tl y, the gr aph in Figure 5, which shows the relat ive performance (compared to the western part of Germany) of East Germany’s GDP. In this case too the initial fall and the later reco very are clearl y visible. We can see, however, that t he recover y of th e global GDP, un like the per capita GDP , almost completely stops after the mid-1990s, remaining on signifi- cantly lower values th an tho se b efore unification. Clearly this is due to the population reduction of Eastern Germany: the East Germany resulting after the integration process is a demo- graphi cally a relati vel y smaller o ne, al thou gh, at th e same time, characterized by greater per capit a income. Southern Italy, instead, has continued to be a real periphery. Moreo ver, it h as been experien cing this st ate for a con siderab ly longer time than East Germany and has therefore already suf- fered large scale migration in the past. However, it should be noted that migration, this time concerning skilled workers above all, seems to be again affecting not only southern Italy but also the whole of Italy, which will perhaps start to assume a peripheral status in its entirety. UE, Nationalities and Social Cohesion From the discussion above we can deduce that if on the one hand it seems unrealistic that the single national Eu ro pean states can continue to play a decisive role i n the global scenario, on the other hand it is clear that the adoption of a single cur- ren cy, without appropriate redistributive measures and indeed in combination with restrictive policies, is generating a reces- sion so marked that it is pushing many European states toward stagnation and economic, social and in so me cases e ven cultural decline. In fact we must not forget that the states which are members of EU are essentially nations, with thousands of years of history, albeit with a common cultural substratum. The eco- nomic differences among the EU member states cannot be bri- dged, if instead of the competitive evaluations and public in- terventions (welfare) of the past, the only strategy used is defla- tionary policies which definitely generate migration causing po- pulation depletion and the reduction of the political weight of entire nationalities. Inter-European migrations cannot be com- pared to those concerning single-nation states. What makes a cohesive societ y is in fact a p articular hu man apt itude: Ben tha- mian altruism. In humankind, in fact, both groups and individ- uals are vehicles of selection, the former due to Benthamian Figure 1. Evolut ion of the relat ive weight of the eastern region s on the Ger- many population in the period 1989-2006 (% values). Source: Mar tinez Oliva, 200 9. In the work of Oliva the percentages of the Eastern Germany population erroneously refer to the Western Ger- many popula t i o n a l o n e . Figure 2. Relative variations of the population in the regions (Nuts2) of Germany in the period 2004-2008. Source: Eurostat. OPEN ACCE SS 48  A. L. PAOLILLI Figure 3. Evolution of the productivity level in East Germany and West Germany in the period 1989-2006 (% values). Source: Martinez Oliva, 2009. Figure 4. Evolution of the per capita GDP of East Germany and West Germany in the period 1989-2006 (% values). Source: Martinez Oliva, 2009. Figure 5. Evolution of the weight of the eastern regions in the German GDP in the period 1989-2006 (% values). Source: Martinez Oliva, 2009. altruism, which is directed toward the group5, therefore favor- ing its cohesion (Paolilli, 2011b), while the individual is related to a combination of selfishness and “binary altruism”, which is directed towards single humans (Paolilli, 2011b; see also Bia- vati, Sandri, & Zarri, 2002; Forges Davanzati, & Paolilli, 2004). Benthamian altruism requires, as a priority, an identification in the group and this identification, of course, is much easier the more the individuals share cultural, economic, social and also territorial elements. A E uro pean Union characterized by many nationalities can- not work if it is based on a structure which, to sustain itself, requires continual sacrifices which, moreover, do not seem to serve the collective well-being but instead, in deference to du- bious economic th eories, feed finan cial in terests whose p roduc- tivity for the whole community is unproven (on this, see Forges Davanzati, 2013). Euro zone countries must manage the appa- ratus of their public administration without monetary sovere- ignty. Ther efore esp ecially tho se who are economicall y and/ or politically weaker, end up either being subject to financial au- thorities like th ose, not democratically elected ( and whose goals may differ from those of the majority of the population), or strongly influenced by the stronger political (and national) enti- ties. All this, in the long run, could cause a decline in identifica- tion with the EU, with political and social consequences. In fact social inequality tends to encourage behaviors which under- mine the institutions both in those who profit from this inequa- lity and, of course, in those who lack power and wealth (Glaes- er & Shleifer, 2002; Glaeser, Scheinkman, & Shleifer, 2003; see also Buchanan, 2008: pp. 200-203). Moreover, when there is a moral distance between benefactors and beneficiaries (in the sense that the latter are not seen by the former as members of their group), the benefactors’ willingness to act unselfishly depends more on considerations of effectiveness (Anen, 2007). In other words, individuals no longer continue to act unselfishly towards st rangers if the y think that th eir actions are ineffecti ve, unlike the case in where emotional proximity is more intense and there is therefore less rationality (pushing behaviors which are apparently less rational but that generate a social cohesion which is at the basis of human societies). Conclusion In the light of the considerations that we have done above, we can conclude that it seems difficult to build a truly unified and d emocratic Europe starting from a monetary union. The n it would be more appropriate to build a Europe that is unified in some respects (e.g. with centralization of government spending for some strategic branches of the Public Administration), but consist of EPS that are more autonomous from the economic point of view, and therefore be able to implement fiscal policies. In other words, to make an analogy with the banking system, Europe should be set up not on the German model of universal bank, which operates in any monetary and financial field, but on that of the multi-purpose group, in which a central manage- ment with strategic functions co-exists with many peripherals which are almost independent from each other and that operate in the specific field s in which th ey are s pecialized . As we have s een above, i n fact, a care ful combinati on of co- operation and competition is what has allowed not only Euro- pean EPS, but also successful companies to grow and prosper. Acknowledgements I thank Guglielmo Forges Davanzati (University of Salento) for some useful suggestions. REFERENCES Anen, C. (2007). Neural correlates of economic and mor al deci sion-ma- king. http://thesis.libr ary.caltech.edu/1561/ Biavati, M., Sandri, M., & Zarri, L. (2002). Preferenze endogene e di- na mich e relazion ali: Un modello coevolu tivo (Endogenou s preferen- ces and relational dynamics: A coevolutionary model). In P. L. Sacco, & S. Zamagni (Eds.), Complessità relazionale e comportamento eco- nomico (Relational complexity and economic behavior) (pp. 431- 5The group, nat ura lly, inc ludes the agent, who sees himse lf as an elem ent of the group. OPEN ACCE SS 49  A. L. PAOLILLI 485). B ologna, IL: Mulino. Buchanan, M. (2008). L’atomo sociale. Il comportamento umano e le leggi della fisica, Milan, Mondadori, Italian edition of The Social Atom (2008 ) . Burker, M. (2009). The Economic unification of Germany, L’Arengo del viaggiatore (The arengo of the traveler), Section Economia e Mercati (Economics and m ar kets), 64. Cesaratto, S., & Pivetti, M. (2012). Oltre l’austerità (beyond austerity), E-boo k pu blished in Micromeg a on-line. Diamond, J. (2006). Guns, germs, and steel. The fates of human socie- ties. New York: W. W. Norton & Comp any. Forges Davanzati, G. (2013). Le pol iti ch e di au s ter it à: Un’Analisi criti- ca (Austerity policies: A cr i tical anal ysis). MarxXXI. www.marx21.it Forges Davanzati, G., & Paolilli , A. L. (200 4 ). Alt ru i sm o, s cam bi e svi - luppo economico (Altruism, trade and economic development). In L. Tundo Ferente (Ed.), La responsabilità del pensare (The responsi- bility of thought) (pp. 289-307 ). Naples: Liguori Editore. Glaeser, E. L., & Shleifer, A. (2002) . The Injustice of Inequality, NBER Working Papers 9150. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. Glaeser, E. L., Scheinkman, J., & Shleifer, A. (2003). The injustice of in- equality, Journal of Monetary Economics, 50, 19 9-222. http://dx.d oi.org/10.1016/S0304-3932(02)00204 -0 Krugman, P. R. (1991). Increasing returns and economic geography. The Journal of Political Economy, 99 , 483-499. http://dx.d oi.org/10.1086/261763 Krugman, P. R. (1998). What’s new about the “New Economic Geogra- phy”. Journal of Political Economy, 14, 7-17. Mandelbrot, B. (1963). The variation of certain speculative prices. Journal of Business, 36, 394-419. htt p://dx.doi.org/10.1086/ 294632 Martinez Oliva, J. C. (2009). Riun i f icazi on e i nt er t ed esc a e p oli t ich e p er la convergenza (Inter-German reunification and convergence polici- es), Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occas ional pape rs) (Issues of economics and finance (Occasional papers)), Banca d’Italia, 51. Myrdal, K. G. (1957). Economic theory and under-developed regions. London : Gerald Duckworth. Paolilli, A. L. (2008). Development and crisis in ancient Rome: The role of Medit erranean trade. Histo rical Soci al Resea rch. An Intern a- tional Journal for the Application of Formal Methods to History, 33 , 274-289. Paolilli, A. L. (2011). Div ari econ omici t errito riali e proces si di fin an- ziarizzazione dell’economia. Il caso del Mezzogiorno nello scenario europeo del dopo Maastricht (Territorial economic disparity and pro- cesses of financing of the economy. The Mezzogiorno in the post- Maastricht European scenario). PhD Thesis, Lecce: Salento Univer- sity. Paolilli, A. L. (2011). Altruism, selfishness and social cohesion. Socio- logy M ind, 1, 145-150 . Paolilli, A. L., & Pollice, F. (2011). Trajectories of state formation in Eurasia: A di scu ssion. Historical Social Research. An International Journal for the Application of Formal Methods to History, 36, 343- 371. Paolilli, A. L., & Pollic e, F. (2 011 ). Finance and centre-periphery dyna- mics: A model. iBusiness, 3, 248-261. http://dx.d oi.org/10.4236/s m .2011.14018 Scheidel, W. (2007). The “First Great Divergence”: Trajectories of post- ancient forma tion in eas tern an d western E uras ia. P r inceton/ Stanford: Working Papers in Classics. Spratt, S. (2009). Development finance, debates, dogmas and new direc- tions. London and New York: Routle dge. Vita, C. (2006-2007). Economie dualistiche e processi cumulativi di divergenza. Il dibattito sui Mezzogiorni d’Euro pa (Dualistic econo- mies and cumulative processes of divergence. The debate on Eu- rope’s South). PhD Thes is, B enev ento: Sannio University. OPEN ACCE SS 50

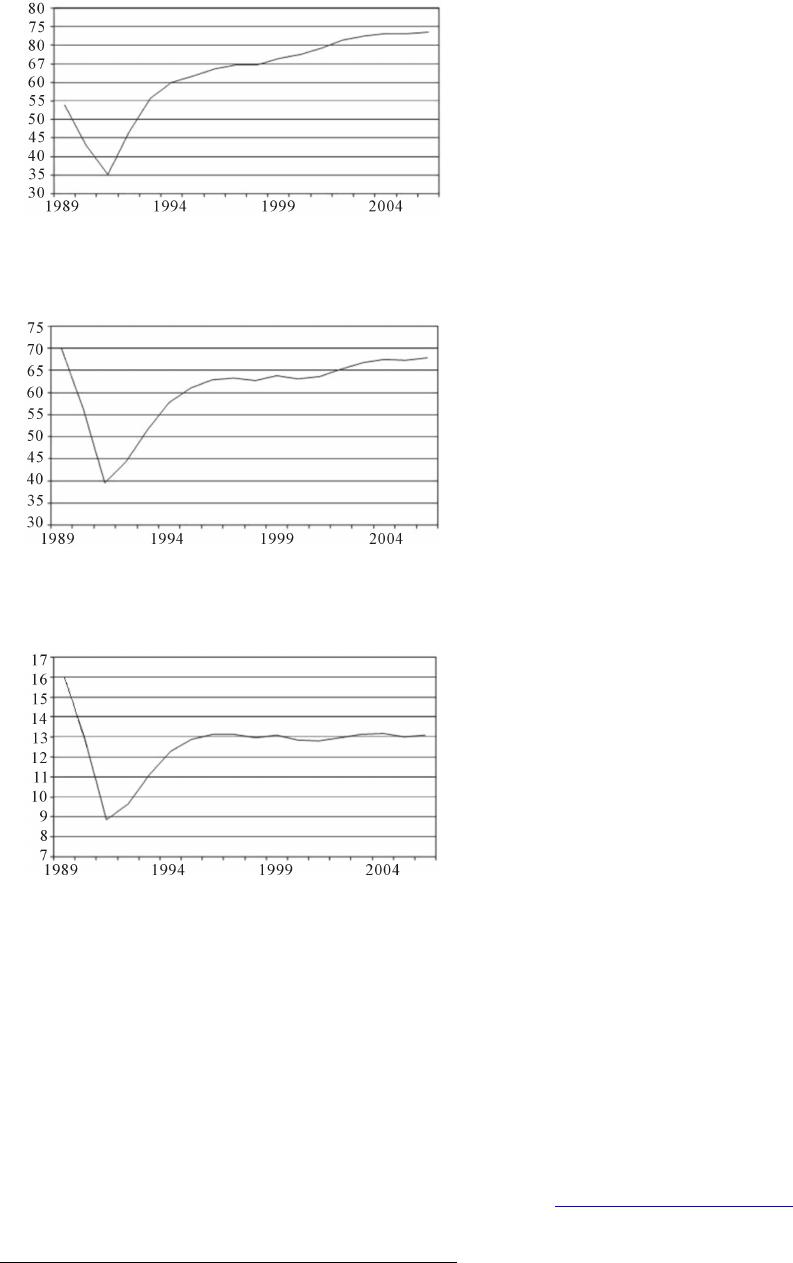

|