Sociology Mind 2014. Vol.4, No.1, 24-30 Published Online January 2014 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/sm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/sm.2014.41003 OPEN ACCESS Civilisations and Capitalism: On Economic Growth and Institutions Jan-Erik Lane* University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany Email: janeklane@googlemail.com Received November 22nd, 2013; revised December 24th, 2013; accepted January 9th, 2014 Copyright © 2014 Jan-Erik Lane. This is an open access article distributed u nder the Creative Commons Attri- bution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved f or SCIRP and the own er of the in tell ectu al p ropert y Jan-Erik Lane. All C o p yright © 2 0 14 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. Theories of political culture have typically refrained from a reinterpretation of the idea of civilisations, as a few well-known traditional approaches to this concept have been severely criticized. Yet, one may probe into the relevance of the concept of a set of civilisations for mankind in the period of globalisation. However, it is not the Weber thesis linking religion with modern capitalism or economic growth that ap- pears most promising today when enquiring into cultural effects. Instead, it is the spread of respect for the rule of law regime, which has a much longer history than the democratic polity. Keywords: Global Capitalism; Institutional Economics; Political Culture; Civilisations; Economic Growth; Rule of Law; Weber’s Thesis; Marxist Approach; Low and High Polit i cs; Principal-Agent Problematic; Due Process of Law; Economic Sociology Introduction The study of political culture ranges from micro level attitu- dinal data about individuals over country macro characteristics to the largest aggregation of civilisations. The categories of ci- vilisations are immense aggregations in the world population, collecting groups of the somewhat 200 countries of the world into a parsimonious set of super groups. Several attempts have been made, but they have all been criticised for either too much simplification or some inherent bias. The emergence of globalisation theory looking upon Planet Earth as a whole in terms of politics, economics and culture makes civilisation analysis relevant again, although this field of study could use more other methods and starting-points than those of for instance Spengler (1918) and Toynbee (1934-1954) focussing upon the life cycle of civilisations or van Sloan with his notion of civilisation leadership as well as Huntington with his somewhat narrow focus upon conflict or clashes (1996). Although the historical study of civilisations received new stimuli from the evolutionary perspective of Diamond (1999), the concepts of birth, life span and death as well as leadership or conflict must be used with extreme care in relation to such macro aggregates as civilisation. A civilisation is a mere statis- tical concept, aggregating first and foremost country similarities or differences. The Debate on Modern Capitalism Typical of the civilisations of the world today is that they are connected through the global market economy, i.e. both aspects of it, namely the real economy on the one hand and the finan- cial economy on the other hand. This ONE market economy is often called “capitalism”, by both people on the Right (with ap- proval) and people on the Left (with critique). Faced with sev- eral civilisations and capitalism, one may enquire into whether the various civilisations on Earth display different relationships to capitalism. But how to approach this notoriously value-loa- ded concept? This is not the place to comment upon the longish discussion surrounding the phenomenon (a) of what we label “capitalism”, from Karl Marx to M. Friedman (1962) over Sombart (1927) and Schumpeter (1989) to Acemoglu and Robinson (2013). It is enough to make a few key distinctions. First, one may separate between capitalism as dynamic eco- nomic process, characterized by swing between expansion and depression, as measured in rates of economic growth—an out- come definition. In this sense, China is a capitalist country, or perhaps the most capitalist in the world. Capitalism is this ap- proach is driven by the search for profits, short-term or long- run, and it could include both capitalisme sauvage and organis- ed capitalism. Second, one could link up modern capitalism with a set of institutions, outlined in the school of Law and Economics (Co- ter and Ulen, 2011), which makes it different from Ancient or Feudal Capitalism. Crucial here is not only the limited liability organisation—Aktiengesellschaft—or the Bourses, but a high degree of economic freedom for both capital and labour, inclu- ding full private property. Organised capitalism involves seve- ral of the rights and duties that enter the concept of rule of law, in the World Bank framework for analysing good governance (WB 2009). According to this meaning, China is not yet a fully capitalist country, especially when taking its high level of cor- Author’s note: Jan- Erik Lane is an independent scholar. He has been full professor at three universities, and visiting professor at many more. J.-E. LANE OPEN ACCESS ruption into account also. Third, it is necessary to reflect upon the value-loaded notion of a civilisation. Alternative lists of civilisations have been sug- gested (Toynbee, 1934-1954), but here we concentrate upon the present vibrant civilisations with important economic activities in both the real and the financial economies. The Weber Thesis In the early 20th century, Max Weber’s painstaking enquiries into the economic ethics of world religions broke the estab- lished racist perspective upon civilisations, typical of late 19th century thinking (Weber, 1915-1920). It re jected any biological basis for the classification of civilisations, very similar in tone to his disbelief in primordialist ethnicity (Weber, 1978). What separate men and women is their belief, and not races, he ar- gued with emphasis against his famous competitor in the enqui- ry into the sources of modern capitalism, namely Werner Som- bart (1992) underling the role of Jewish merchants in furnishing capital (Langer, 2012). And here religion constitutes a most powerful source of belief-systems in the form of articulated dogmas of faith. Weber focussed upon the economic effects of the world re- ligions, searching for the origins of modern capitalism, which he equated with the requirements of rationality or modernisa- tion. Of the link he suggested in 1904-05: inner-worldly asce- tism—Protestantism and market economy, there remains noth- ing today, as other civilisations or economic centres display pre- sently as much if not more economic dynamism that the West- ern one. Let us instead search for civilisation effects outside of the global economic system, within politics. In Marxist thought, one encounters another framework for analysing capitalism (Wolf, 1982 ). Whereas Weber spoke of An- cient or slave capitalism, feudal or agrarian capitalism and state capitalism (tax farming), Marxists restrict “capitalism” for the pe- riod of machine ca pital linked large scale social la bour in the in- dustrial and urbanize d setting wit h global link s to two older ty pe s of economic systems, the kin ordered (tributary) mode of produc- tion and the mercantile economy with merchants’ capital. I will argue that the countries of the world today display dif- ference in the respect for rule of law as well as that this varia- tion has a civilisation background. The crucial importance of the rule of law institutions become intelligible when put into the principal-agent framework for analysing politics and political regimes, derived from the new economics of information. How to Identify a Civilisation: What Cultural Item to Use? Culture is employed to single out a set of civilisations, but culture covers a huge variety of items, such as behaviour, be- liefs and artefacts. One may consider a number of criteria with which to classify countries into a set of civilisations, inter alia: 1) Language families; 2) Religion; 3) Values; 4) Legacies; 5) Economic mode of production; 6) Geography. Since civilisations are constructed by the scholar, the choice between 1) - 5) depends upon what one intends to illuminate or show. Given the sharply increasing relevance of religion in the period of globalisation, I will employ the criterion 2) above. Again, one may debate what a fruitful classification of the religions in the world today would amount to. A number of criteria have been used: 1) Monotheistic—polytheistic; 2) Animism; 3) Magic; 4) Salvation: Inner-worldly—outer-wordly; 5) Ascetics: World-rejecting against world mastering asce- tism; 6) Ethical—prophetical; 7) Western—Eastern. If we accept the Weber’s idea that religion has had a perva- sive impact upon social organisation and politics, then it seems most convenient to focus upon the world religions, i.e. the largest of them: Catholicism, Protestantism, Orthodox, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism as well as Shintoism. However, the growing number of atheists or agnostics should be taken into account, as these groups are of considerable size in both Western Europe and Eastern Europe, in Russia as well as China. Thus, strong Communism is to be found in Far East Asia, where religion is barely tolerated. One could, of course, have included several other religions or sects, but they are seldom predominant in a country. Using countries as the basis for an enquiry into religion, one may sug- gest a parsimonious list of eight civilisations: 1) Western: Mainly Protestantism + some Catholicism; 2) Latin America: Catholicism with some Protestantism; 3) Orthodox: Greek and Russian Orthodox; 4) Arab Islam; 5) Non-Arab Islam; 6) Sub-Saharan Africa: animism, Ch r istiani ty, Islam; 7) Hindu; 8) Buddhism, Confucian/Taoist, Shintoism; 9) Communist; 10) Pacifi c: animism, Christia nity. One may point out that these gro ups of countries are not com- pact in terms of culture, not even when the criterion is world re- ligion or atheism. Thus, religious minorities are to be found in most countries. Yet, the theory that the world religions have had strong so- cial implications implies that they have formed parts of legacies, or historical traditions that linger one even, if the religious fer- ment may have subsided. In the case of Communism, it is the atheist legacy that counts, leading often to the suppression of religion, as in China at times. Historical Traditions Neo-institutionalism and economic sociology has empha- sized the importance of long lasting practices, or customs for social, economic and political outcomes. Such legacies may comprise patterns of behaviour, clusters of attitudes as well as long lasting institutions. Civilisations are historical traditions, but historical traditions could be smaller in scope and range than entire civilisations. Historical traditions could be based upon other kinds of culture than religion, such as ethnicity and political history. One may argue that the civilisation categories above harbour such a number of historical traditions, like for instance the following tentative but not exhaustive listing: 1) Lat in America: Spanish and Portugal legaci es, Catholicism; Indian legacies, the l atifundia mode of production, caudil los, etc.;  J.-E. LANE OPEN ACCESS 2) Sub-Saharan Africa: colonialism, tribal society, kinship, ethnic heterogeneity; 3) Orthodox legacy: Hierarchy in state, society and church; tsarism and caesaro-papism; the patriarch legacy, serfdom; 4) Islam: Submission to religion, religious jurisprudence, gen- der inequality, oriental despotism; the madhi; 5) Hindu legacies: Incarnation and magic, oriental despotism, castes and gurus; indentured labour, share cropping; 6) East and Far East Asian traditions: the sangha organisa- tion or monasteries, oriental despotism, tantrism, spiritism. 7) Pacific countries: clans, tribes, ratu, colonialism, animism; 8) Western traditions: secularisation; individualism; institu- tionalisation of the sciences; 9) Communist legacy: planned economy, atheism, state con- trol over society; One may wish to add numerous other traditions to the list above, as it would be difficult to be exhaustive here. Historical developments tend to be complex, meaning that various tradi- tions may coexist with each other under more or less tensions. When different traditions occur, it may be almost impossible to tell which is most important. Important for what? One could examine present day outcomes. Capitalism Today Weber saw modern capitalism, or the institutions of the mar- ket economy, as the giant difference maker among the civilisa- tions of the world, resulting in economic rationality meaning affluence and power. If capitalism is merely a motivation force, then it has always existed as the incessant search for economic advantages, profits and success. However, if “capitalism” stands for a set of institutions, or rules, then one may wish to enumer- ate a number of different types of capitalisms: ancient, state, fe- udal, modern, etc. Weber summed up his position as follows: “It is only in the modern Western world that rational capi- talistic enterprises with fixed capital, free labor, the rational specialization and combination of functions, and the allocation of productive functions on the basis of capitalistic enterprises, bound together in a market economy, are to be found.” (Weber, 1978: 165). But the institutions of modern capitalism can be exported and adopted by other civilisations, learned and refined, which is exactly what occurred in the 20th century. Thus, even if Protes- tantism, or Protestant ethics had something to do with the ori- gins of modern capitalism in the West, which is an essentially contested matter, it could never guarantee any persisting ad- vantage. Today, modern capitalism, at least when measured in terms of output, is perhaps stronger in East and South East Asia, with a few strongholds also within Islam. Modern capitalism is not a difference maker in the world to- day. All civilisations practice it. If Weber perhaps led us in the wrong direction by focussing upon the amorphous phenomena labelled “capitalism”, then we must as ask: Why did he not enquire into the civilisation sources of his famous ideal-types of political power, or legitimate authority? I will show below that the civilisation variation remains as large today as it was in 1900, when it comes legal-rational authority, interpreted as the rule of law. Capitalism as Economic Dynamism One may raise the question whether we are witnessing the definitive eclipse of what Weber theorized as the dominance of modern Western capitalism, as we do not find European or American countries among top most dynamic countries in the world today. Table 1 shows economic growth among the G20 countries, for 2000-2006 (a) and 2007-2011 (b), where the eco- nomic success of the BRIC is obvious. Research in the 20th century had to ask: Did Weber get it right when he argued in several painstaking enquiries into the world religions that other civilisations than the Western could not bring forward the market economy, or modern capitalism (Weber, 1988). The debate concerning his portraits of some of the chief world religions has not ended today, as scholars ask: Did Weber harbour an occidental bias, i.e. orientalism? Here I will underline not his omission of Catholicism and Orthodoxy, or his brief as well as rather negative remarks upon Islam due to its social effects. But instead I will emphasize that he concen- trated exclusively upon economic outcomes in his civilisation enquiry. Institutional Capitalism Weber identified four types of political regimes: naked power, traditional, charismatic and legal-rational authority. However, he was not clear about the nature of the last type, Table 1. Economic growth in G20 countries. (a) (b) Argentina ARG 0.17978 0.24650 Australia AUS 0.19123 0.09261 Brazil BRA 0.17613 0.14672 Canada CAN 0.15345 0.03472 China CHN 0.58498 0.36754 France FRA 0.10399 0.00055 Germany DEU 0.0 6607 0.02390 India IND 0.41598 0.27488 Indonesia IDN 0.28449 0.22633 Italy ITA 0.07067 −0.04596 Japan JPN 0.07621 −0.03096 Republic of Korea KOR 0.27012 0.12290 Mexico MEX 0.14159 0.03974 Russia RUS 0.37593 0.05379 Saudi Arabia SAU 0.21701 0.15330 South Africa ZAF 0.24256 0.07929 Turkey TUR 0.28930 0.12620 United Kin gdom GBR 0.16739 −0.02858 United States USA 0.14494 0.00712 The European Union EUU 0.13451 −0.00314 Euro Area EMU 0.11019 −0.00788 Note: ( )() ( ) { } Economic growth =natural logarithmGDP year 1natural logarithmGDP year 100%nn−∗ . Sources: USDA-ERS: http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/international-macroeconomic-data-set.asp x; World ban k : http://databank.worldbank.org/data/home.aspx. J.-E. LANE OPEN ACCESS linking wrongly—I wish to argue—legal-rational authority with his ideal-type model of bureaucracy. Typical of legal-rational authority is, I would wish to emphasize, government based upon rule of law. Let us first state the definition of “legal au- thority” from Weber: “The validity of the claims to legitimacy may be based on: 1. Rational grounds—resting on a belief in the legitimacy of en- acted rules and the rights of those elevated to authority under such rules to issue commands (legal authority).” (Weber, 1978: 215) The key terms in this general definition is rules or institu- tions. Yet, he moves on to equate legal-rational authority with bureaucracy: “The purest type of exercise of legal authority is that which employs a bureaucratic administrative staff.” (Weber, 1978: 220). Yet, bureaucracy as a mechanism for carrying out the poli- cies of rulers has, historically speaking, never operated accord- ing to the Weberian ideal-type. Bureaucracies have been inva- ded by affective ties, tribal loyalties and opportunistic selfish- ness. 20th century research into the bureaucratic phenomenon has resulted in numerous findings that question the applicability of Weber’s bureaucracy model. As a matter of fact, bureaucra- cies can support traditional domination, as within Chinese Em- pires or the Ottoman rule. It may also figure prominently in charismatic rulership, as with The Third Reich or the Soviet State. Legal-rational authority emerges in a state that honours rule of law. This involves the employment of LAW, both in high politics and in low politics. It differs from all other forms for the exercise of political power by complying with norms and by offering ways to correct abuses of these norms. Thus, this re- gime is not only legal but also rational in the meaning of the introduction and observation of a set of norms that are secular in nature, protecting the common best of the political commu- nity. This legal-rational dispensation, ranging from constitutional norms at the top to legality and reasonable principles for day- to-day interaction at the bottom, does not have to harbour the democratic polity. What legal-rational authority entails is the following (Raz, 2009): 1) Legality: regulations are sanctioned by laws that are sanc- tioned by a constitution, or lex superior; 2) Predictability of law enforcement: laws and regulations meet with effective enforcement and wide-spread respect; 3) Equality under the law; 4) Autonomy of the judiciary; 5) Natural reason: no torture, no arbitrary seizure or arrests, no prison sentence without court procedures, property rights. The occurrence of legal-rational aut hority, i.e. rule of law may be mapped using the governance indicators from the World Bank Governance project. Rule of Law Indica t ors Rule of law—in Germa n Rechsstaat—include both low poli- tics—the predictable institutionalisation of transparent norms in everyday life—and high politics—the weight of constitutional law in government and administrative law in public services. In the World Bank Governance project, one encounters the following definition of “rule of law”: Rule of Law (RL) = capturing perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of soci- ety, and in particular the quality of contract enforcement, pro- perty rights, the police, and the court, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence (Kaufmann, Kraay, & Mastruzzi, 2010: 4). RL is explicitly separated from “voice and accountability”, which is defined as follows in the WB project: Voice and Accountability (VA) = capturing perceptions of the extent to which a country’s citizens are able to participate in selecting their government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and a free media (Kaufmann, Kraay, & Mastruzzi, 2010: 4). The WB Governance project suggests four additional dimen- sions of good governance (political stability, government effec- tiveness, regulatory quality and the control of corruption), but we will only enquire into RL here. The WB Governance project employs a host of indicators in order to measure the occurrence of RL around the globe, which results in a scale from −2 to +2. Rule of law with the WB is a complex index, composed of the addition of many often used indicators, such as: 1) Fairness of judicial process 2) Occurrence of political violence 3) Confidence in courts and police forces 4) Security of persons and goods 5) Independence of judiciary 6) Property rights. It is true that many countries are so-called constitutional de- mocracies, meaning that they score high on both these two composite indices in the WB Governance Project, rule of law on the one hand and voice and accountability on the other hand. However, the two concepts are distinguishable. From an his- torical point of view, it must be emphasized that rule of law developed much earlier than the democratic polity. One may wish to go beyond this conventional classification of political regimes, based upon the Western concept of de- mocracy, and enquire into the relevance of rule of law for any country, whether liberal, illiberal or anarchic. In whatever po- litical regime a human being may live, he/she would value in- stitutions that promote: Transparency of norms in low politics or daily life, constitutionality of high politics, court independ- ence from politics and religion, immunities: a list of rights like e.g. habeas corpus. Thus, one may advocate rule of law reforms in all kinds of political regimes without the accusation that one wants to force countries to adopt Western type democracy. Several countries score low on democracy, according to the WB Governance in- dices, but they achieve a moderate level of rule of law. Let us look at the global variation in rule of law, as measured by the WB. Here, we will employ the notion of a civilisation, as it of- fers a high level set of aggregates, suitable for globalisation analysis. Cultural Outcomes: Civilisations Matter Approaching political culture as a set of legacies, the ques- tion that this interpretation of civilisations raises is what the more specific social and political impact has been for the pre- sent. Broadly speaking, one may search for cultural effects in either the economy—affluence—or in politics—democracy. The former approach is distinctly Weberian, whereas the latter per- spective figures prominently in the theory of civic culture. Here, I will target the rule of law, which is not identical to  J.-E. LANE OPEN ACCESS either the standard economic outcomes or the occurrence of the democratic regime. Concerning affluence and culture—the We - ber thesis, it has little relevance for the world today, as other civilisations than the Western have adopted the institutions of capitalism with considerable success. With regard to the de- mocratic political system, it can be argued that it is too much of a dichotomy. One cannot expect that the ideal-type of competi- tive democracy with party governance could be introduced in each and every country, at least not in the short run. Let me focus upon a variable that allows for a large variation and that is related to both the market economy and democracy, namely the rule of law. The rules inherent in the notion of rule of law date far back into political history and Ancient philoso- phy. The Governance Project of the World Bank has made a tre- mendous effort at quantifying the occurrence of rule of law, employing all the indices in the literature. The findings are presented in a scale ranging from +2 to −2 that is an interval scale. Ta ble 2 present s the aggregated score s for the civilisations introduced above. The eta squared statistic from ANOVA—.54—suggests that civilisation is indeed highly relevant for understanding the country variation in the respect for rule of law. Some of the civilisations display negative overall scoring, although the high standard deviation should be taken into account. Thus, the Communist, Muslim NON-Arab and African civ ilisations score negative, which is also true of the Orthodox civilisation. We also find negative scores for the Hindu civilisation, but it only comprises two countries: India and Nepal. One may perhaps have expected a more negative score for the Arab civilisation, but the scores for several of the countries in this group is slightly positive: the UAE, Kuwait, Qatar for example. Both Hong Kong and Singapore score strongly positive, like Japan and South Korea. It should perhaps be pointed out that poverty accounts to some extent for the disrespect for due process of law (see Fi- gure 1). However, culture also matters in the form of civilisations. The Latin American civilisation has still some way to go before the overall ranking is positive. But compared with the 1980s, major improvements have been accomplished. Importance of Rule of La w One may discuss the relevance of rule of law from two dif- Table 2. Civilisations and rule of law 2009. Civilization Mean Std. Dev. Freq. Communist −0.755 0.383 6 Hindu −0.533 0.643 2 Moslem NON Arab −0.724 0.656 21 Africa −0.801 0.622 38 Arab −0.304 0.715 18 Asia 0.475 0.963 9 Latin America −0.185 0.788 34 Orthodox −0.507 0.355 8 Pacific −0.187 0.630 16 Western 1.200 0.668 38 Total −0.107 0.984 190 Sources: WB Governance Project (2009) Governance matters: Aggregate and in- dividual governance indicators 1996-2008. Figure 1. Rule of law and affluence (GDP per capita). 0.582 1000 0 -1000 -2000 6.00 8.00 10.00 12.00 2000 J.-E. LANE OPEN ACCESS ferent angles, the micro on the one hand and the macro on the other hand. Thus, rule of law may matter for single individuals, or ordinary men and women. Or it has a clear impact upon the political system and the structuring of political institutions. Micro or Low Politics For the individual person, the implementation of some form of rule of law regime, or set of institutions would affect daily considerably. Thus, the single individual would cherish: Predictability: Public law when properly implemented makes it possible for people to increase the rationality of behaviour. They know what rules apply, how they read as well as how they are applied consistently. This is very important for the making of strategies over a set of alternatives of action. Transparency: Societies operate on the basis of norms pro- hibiting, obligating or permitting certain actions in specific si- tuations. Rule of law entails that these norms are common knowledge as well as that they are not sidestepped by other im- plicit or tacit norms, known only to certain actors. Due Process of Law: When confli c t s occur either between in- dividuals or between persons and the state, then certain proce- dures are to be followed concerning the prosecution, litigation and sentencing/incarceration. Thus, the police forces and the army are strictly regulated under the supervision of courts with rules about investigations, seizure, detainment and prison sen- tencing. No one person or agency can take the law into their own hands. Fairness: Rule of law establishes a number of mechanisms that promote not only the legal order, or the law, but also justice, or the right. For ordinary citizens, the principle of complaint and redress is vital, providing them with an avenue to test each and every decision by government, in both high and low poli- tics. Here one may emphasize the existence of the Ombudsman, as the access to fairness for simple people. People have certain minimum rights against the state, meaning that government faces definitive duties concerning the protection of life and per- sonal integrity. Thus, when there is due process of law—proce- dural or substantive—one finds e.g. the habeas corpus rights. One could dare suggest that a majority of individuals in al- most each and every country would wish to live under these principles. Macro or High Politics Rule of law at the macro le vel is conducive to constitutional- ism in high politics. Constitutionalism was identified already in Roman political thought as the best regime, with Cicero and his painstaking analysis of republicanism (Everett, 2003). It com- prises: Lex superior: If the making of single decisions by the au- thorities is regulated by agency rules, and agency rules by ad- ministrative law, and administrative law by ordinary legislation, then what regulates legislation? Ultimately, one arrives at Kel- sen’s Basic Norm that both legitimates and restrains the rule of law regime, in the form of a constitution. Thus, we have today: Secularism: In terms of religion, it adheres to a secular state based upon religious tolerance. When a state is identified with some religion or religious sect, then it cannot maintain neutral- ity and anonymity in relation to all groups in society. The idea of multiculturalism is as relevant for ethnically divided socie- ties as for countries with high religious heterogeneity. Separation of Powers: In order to have respect for the law as the key instrument for governing society and regulating the state, legislation, policy-making and implementation as well as law adjudication must somehow be separated. Under rule of law, this separation of powers targets the political elite active in the state, with the claim that it has to be divided into three dif- ferent elites: legislators, governors or governments and courts. Counter-weighing Powers: Under the rule of law regime there could be no single source of political power, or a hierar- chical order of command. Instead, it favours multiple centres of power, or pluralism. Separation of powers enhances checks and balances in the state. Court Independence and Judicial Integrity: Government un- der the laws is not feasible unless the judicial branch of gov- ernment rests upon the interpretation of law as impartiality, with regard to both government and civil society. Constitutionalism, harbouring the rule of law regime, is to- day combined with the democratic polity in almost 50 per cent of the states of the world. However, it is also relevant for non- democratic polities. Conclusion: Solving the Principal-Agent Problematic in Politics The significance of the rule of law regime derives from the omnipresent principal-agent problematic in the state, both with regard to policy-making and policy implementation. Political elites—whether they are politi cians, royal family , religious lea- ders, bureaucrats or professionals—must be seen as the agents of the population. How are they to be selected, monitored, re- munerated and evaluated as well as held accountable, given the omnipresence of asymmetric information (Rasmusen, 2006)? The rule of law regime solves this problem by two mechani- sms: 1) Government under the laws restraining political agents; 2) Checks and balances within the state among the agency elites with counter-weighing powers. The respect for rule of law today occurs unevenly in the ma- jor civilisations of the world. Where the enforcement of its principles is weak, like in several countries in the Muslim civi- lisations, in many states in Sub-Saharan Africa as well as in parts of the Orthodox civilisation, people suffer from politics. The so-called West still enjoys a comfortable advantage in terms of due process of law, both procedural and substantive, which should be emphasized when scholars speak of the de- cline of the West (Ferguson, 2012). Acemoglu and Robinson (2013) show that the key rules in the society, its institutions, have a large impact upon cou ntry af- fluence and wealth. To vindicate their theory that the central norms in society explain how the key elements in the neo-clas- sical growth model above develop over time, they construct two ideal-type models of institutions in a country: extractive rules and inclusive norms. The former set of institutions destroys economic growth whereas the latter set of rules promotes it, when properly enforced. “Extraction” covers all kinds of phenomena where whatever affluence exists are captured and dissipated: wars, looting, ex- ploitation, monopoly and oligopoly, corruption, embezzlement, patronage, and so forth. Inclusive norms institutionalize the op- posite phenomena: surplus sharing, free entry, innovation, pro- perty rights, honesty in contracting, an open society with peace based upon a flourishing competitive market economy. J.-E. LANE OPEN ACCESS To put it somewhat differently, inclusive economic and po- litical institutions solve the principal-agent problems in so-called capitalist democracies, favouring organised capitalism. REFERENCES Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2013). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperit y and poverty. London: Profile Press. Coter, R. B., & Ulen, T. (2011). Law and economics. New York: Pear- son. Diamond, J. (1999 ). Guns, germs, and steel: The fates of human societi- es. New York: Norton. Everett, A. (2003). Cicero. New York: Random House. Ferguson, N. (2012). The great degeneration. London: Penguin. Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Huntington, S. (1996). The clash of civilisations. New York: Simon and Schuster. Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & M as tru zzi, M . (20 10 ). Gover na n ce matter s VIII: Aggregate and individual governance indicators 1996-2008. Washington DC: World Bank Development Research Group, Macro- economics and Growth Team. Langer, F. (2012). Werner sombart, 1863-1941 (3rd ed.). Mu nich: C .H. Beck. Morris, I. (2011 ). Why the west rules—For now: The patterns of histo- ry, and what they reveal about the future. New York: Picador. Rasmusen, E. (2006). Games and information. Oxford: Blackwell. Raz, J. (2009). The authority of law. Oxford: Oxford U.P. Schumpeter, J. (1989). Essays: On entrepreneurs, innovations, business cycles, and the evolution of capitalism. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers. Sombart, W. (1927, 1992). Der moderne kapitalismus I-III. Munich: DVT Taschenbuch. Spengler, O. (1918). Der untergang des abendlandes. Wien: Braumül- ler. Toynbee, A. (1934-1954). A study of history, Bd. I-X, London. Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society. Berkeley: University of Cali- fornia Press. Weber, M. (2001). The protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. London: Routledge. Weber, M. (1988). Gesammelte aufsätze zur religionssoziologie I-III. Tübingen: J C B. Mohr. Wolf, E. R. (1982). Europe and the people without history. Berkeley: University of California Press. World Bank (2009). Governance matters 2009: Worldwide governance indicators 1996-2008. Was hi ngton DC: World Bank.

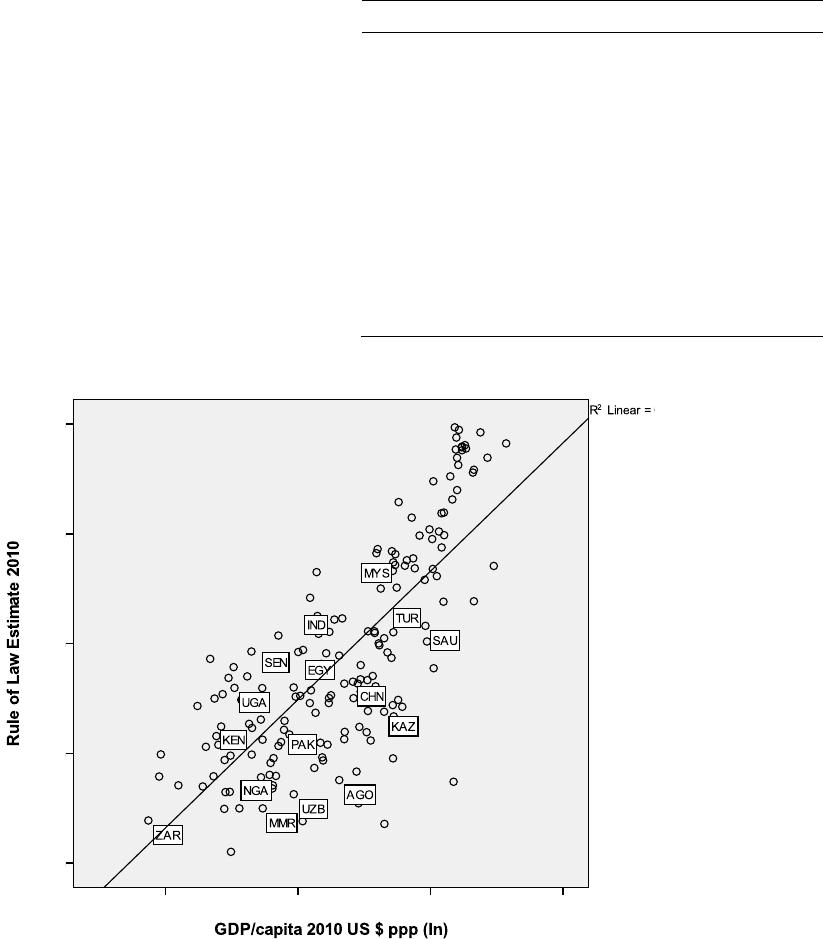

|