Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

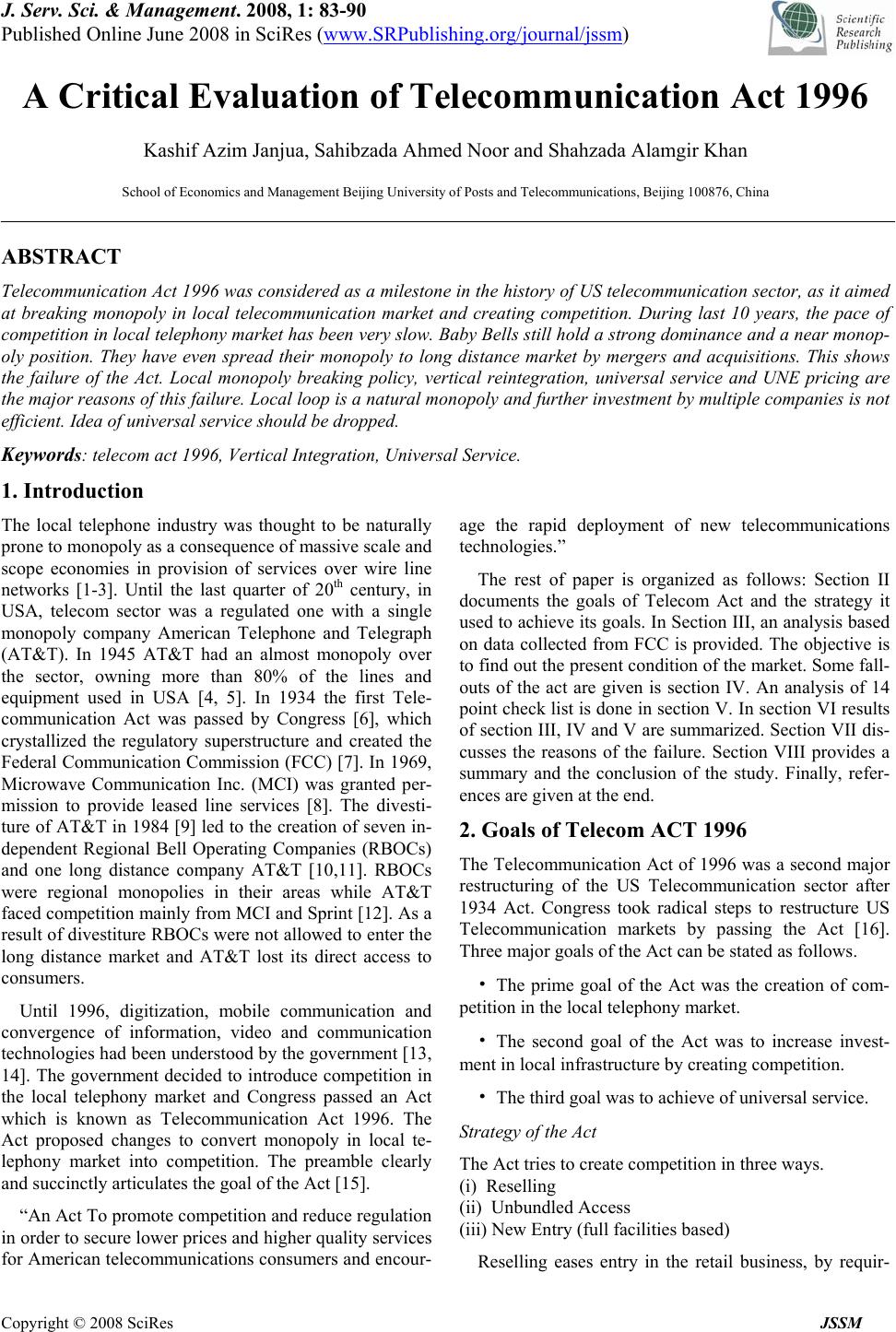

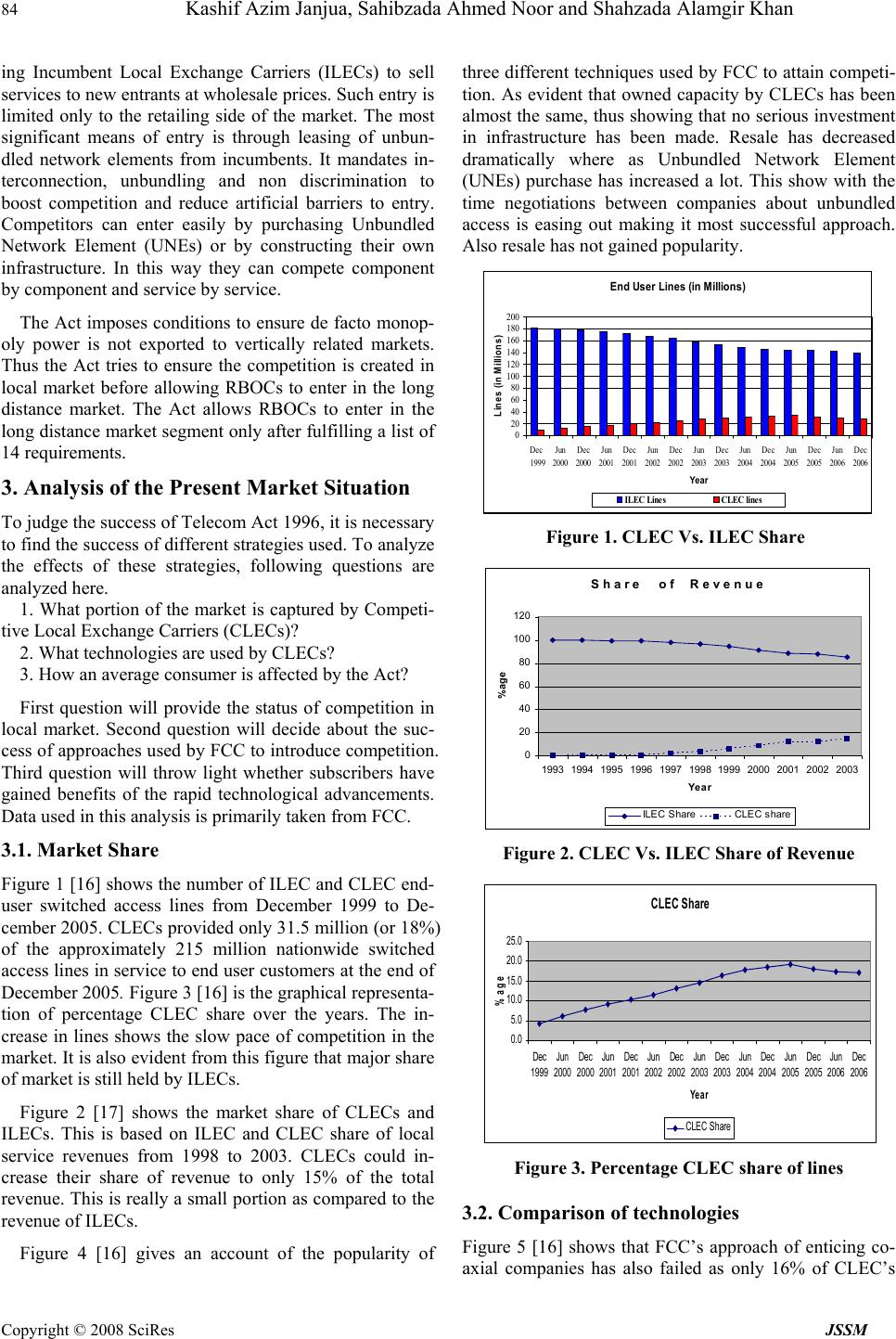

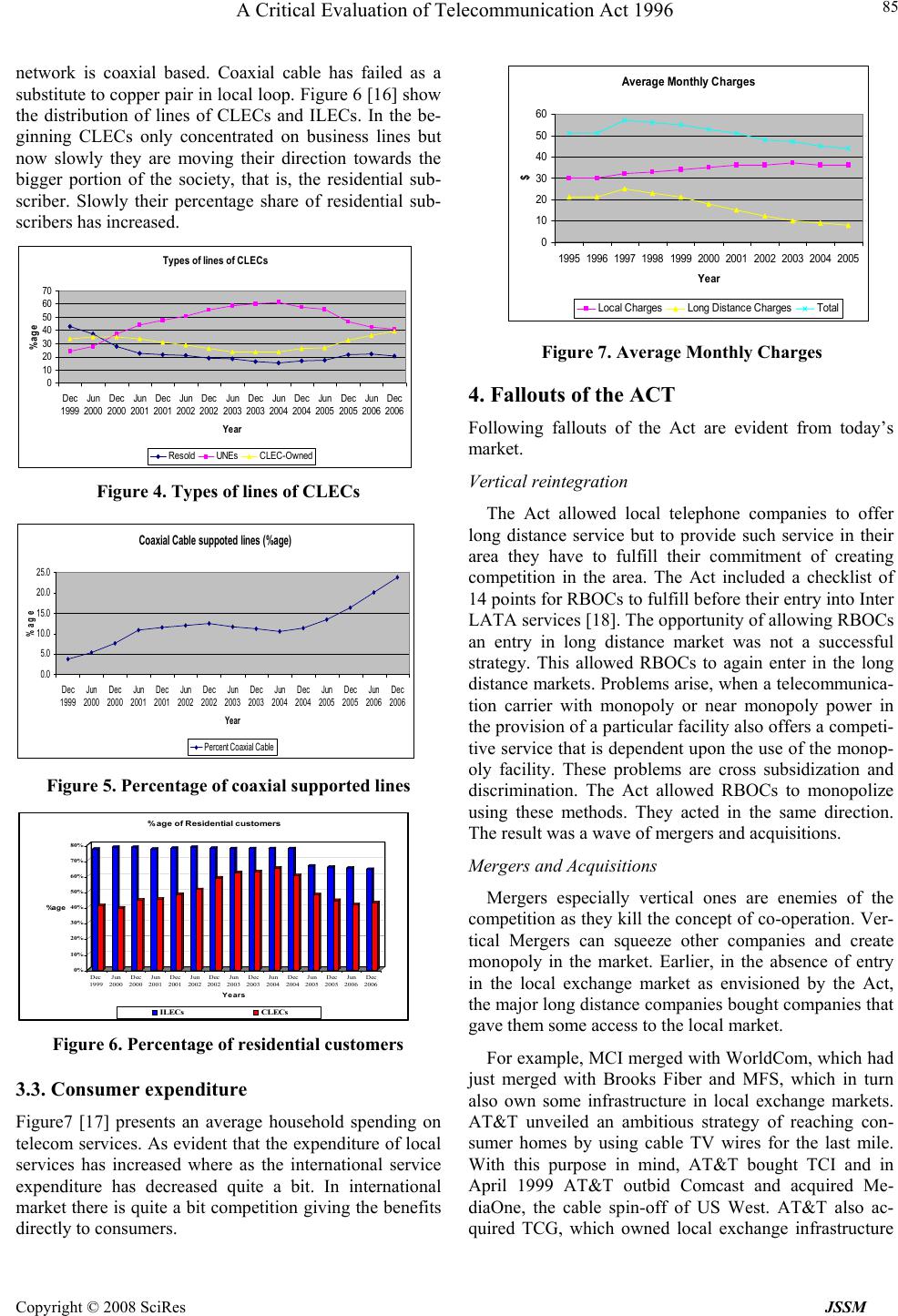

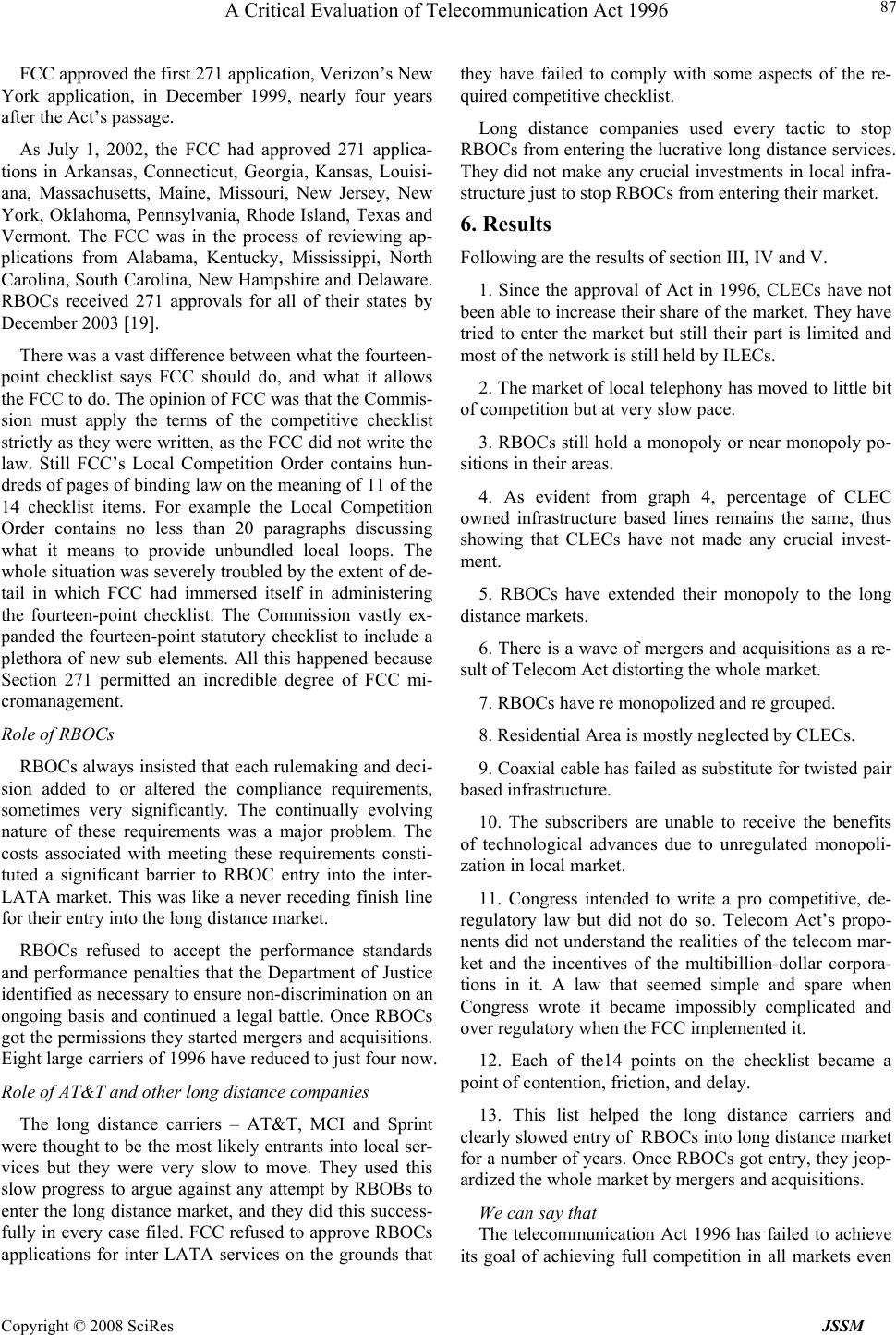

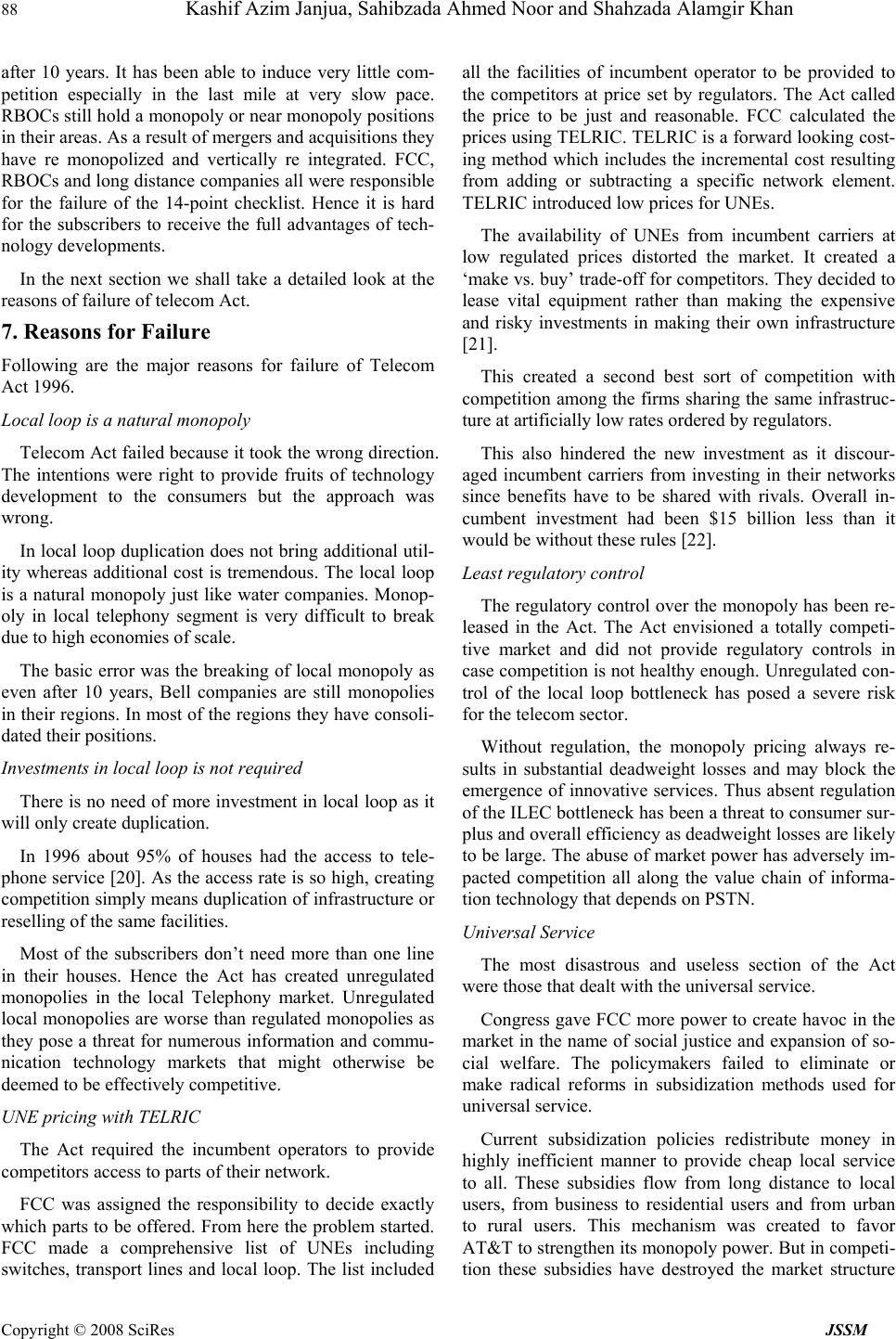

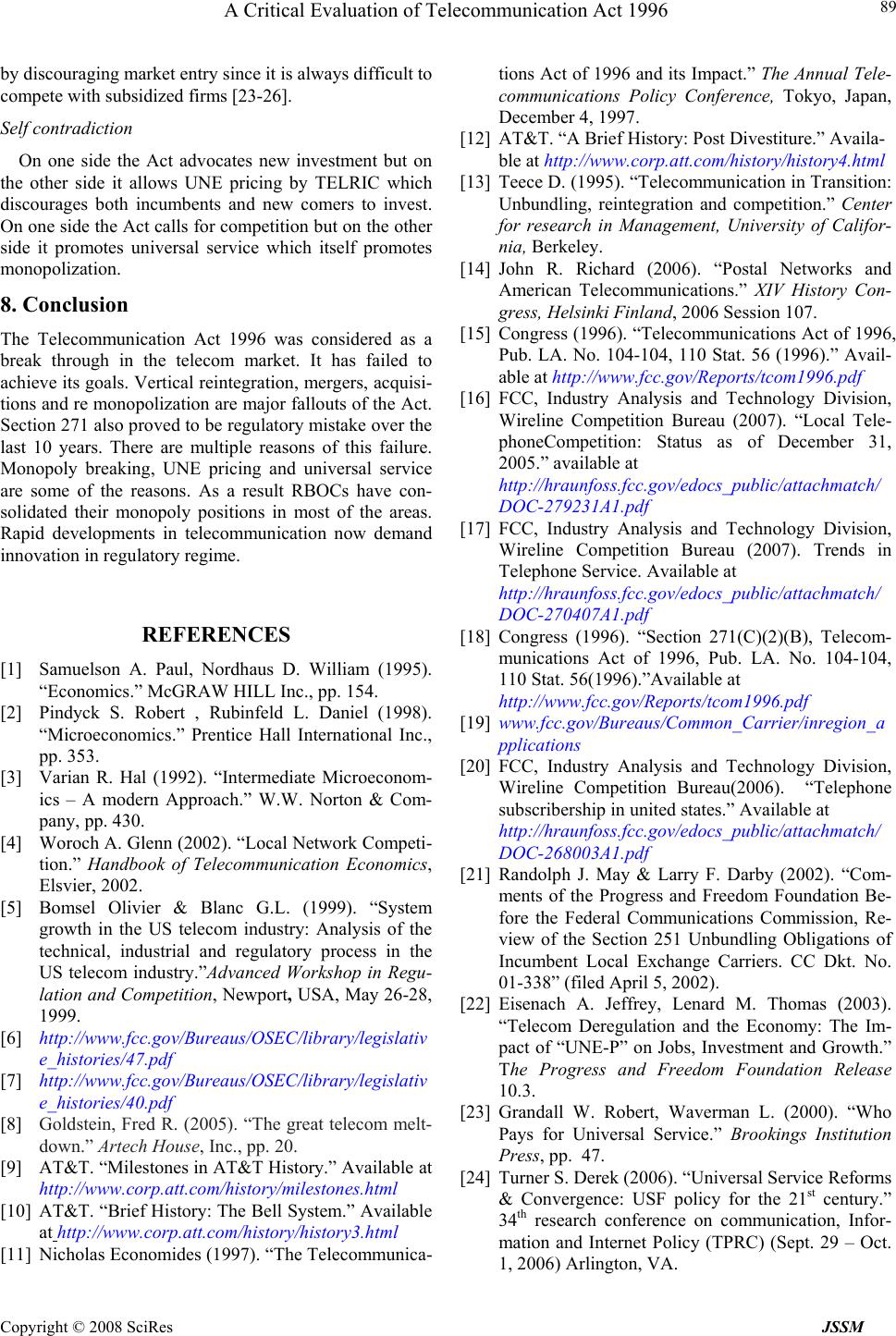

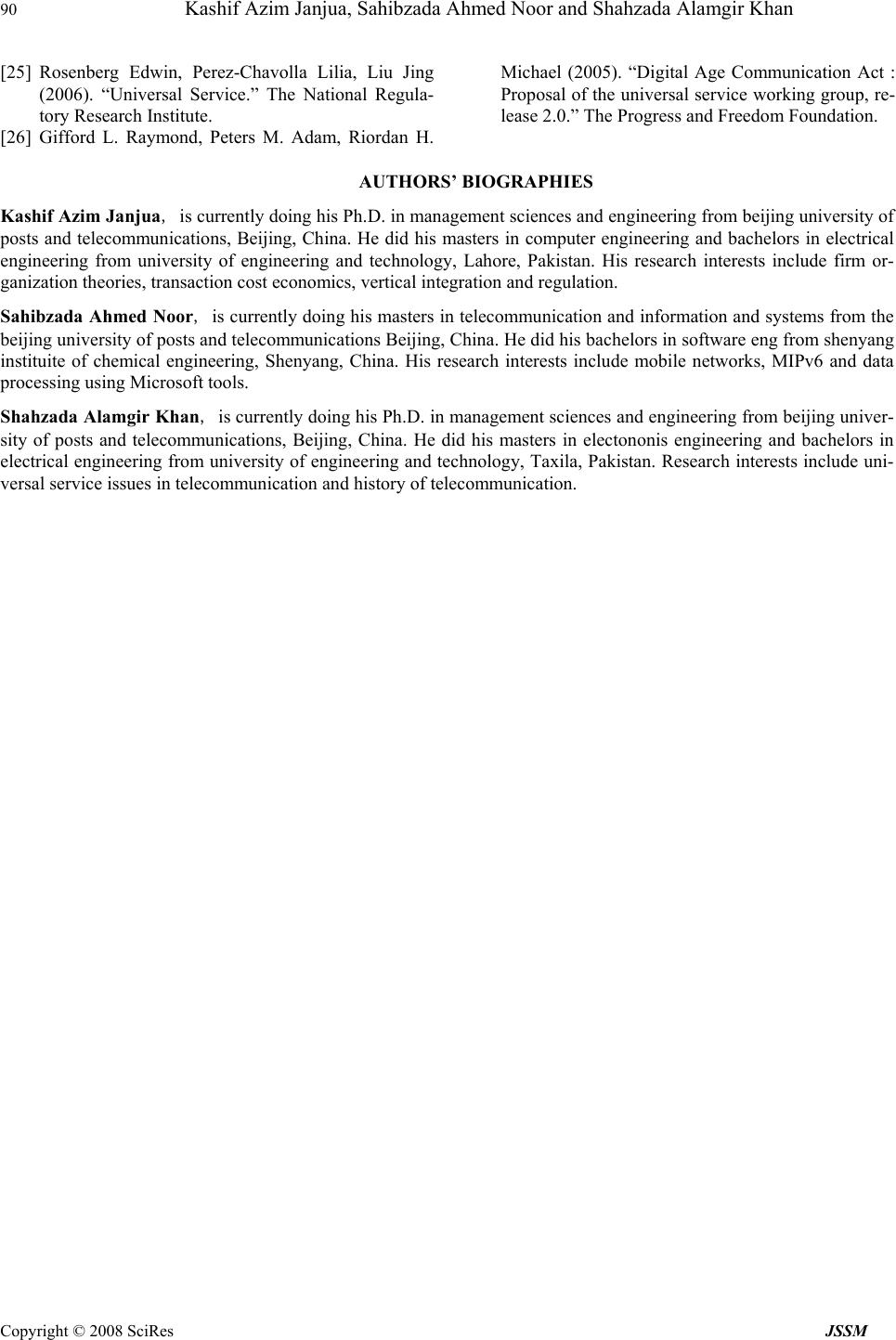

J. Serv. Sci. & Management. 2008, 1: 83-90 Published Online June 2008 in SciRes (www.SRPublishing.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM A Critical Evaluation of Telecommunication Act 1996 Kashif Azim Janjua, Sahibzada Ahmed Noor and Shahzada Alamgir Khan School of Economics and Manage ment Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, B eijing 100876, China ABSTRACT Telecommunication Act 1996 was considered as a milestone in the history of US telecommunication sector, as it aimed at breaking monopoly in local telecommunication market and creating competition. During last 10 years, the pace of competition in local telephony market has been very slow. Baby Bells still hold a strong dominance and a near monop- oly position. They have even spread their monopoly to long distance market by mergers and acquisitions. This shows the failure of the Act. Local monopoly breaking policy, vertical reintegration, universal service and UNE pricing are the major reasons of this failure. Local loop is a natural monopoly and further investment by multiple companies is not efficient. Idea of universal service should be dropped. Keywords: telecom act 1996, Vertical Integration, Universal Service. 1. Introduction The local telephone industry was thought to be naturally prone to monopoly as a consequence of massive scale and scope economies in provision of services over wire line networks [1-3]. Until the last quarter of 20th century, in USA, telecom sector was a regulated one with a single monopoly company American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T). In 1945 AT&T had an almost monopoly over the sector, owning more than 80% of the lines and equipment used in USA [4, 5]. In 1934 the first Tele- communication Act was passed by Congress [6], which crystallized the regulatory superstructure and created the Federal Communication Commission (FCC) [7]. In 1969, Microwave Communication Inc. (MCI) was granted per- mission to provide leased line services [8]. The divesti- ture of AT&T in 1984 [9] led to the creation of seven in- dependent Regional Bell Operating Companies (RBOCs) and one long distance company AT&T [10,11]. RBOCs were regional monopolies in their areas while AT&T faced competition mainly from MCI and Sprint [12]. As a result of divestiture RBOCs were not allowed to enter the long distance market and AT&T lost its direct access to consumers. Until 1996, digitization, mobile communication and convergence of information, video and communication technologies had been understood by the government [13, 14]. The government decided to introduce competition in the local telephony market and Congress passed an Act which is known as Telecommunication Act 1996. The Act proposed changes to convert monopoly in local te- lephony market into competition. The preamble clearly and succinctly articulates the goal of the Act [15]. “An Act To promote competition and redu ce regu lation in order to secure lower p rices and hig her qu ality services for American telecommunications consumers and encour- age the rapid deployment of new telecommunications technologies.” The rest of paper is organized as follows: Section II documents the goals of Telecom Act and the strategy it used to achieve its goals. In Section III, an analysis based on data collected from FCC is provided. The objective is to find out the present condition of the market. Some fall- outs of the act are given is section IV. An analysis of 14 point check list is done in section V. In section VI results of section III, IV and V are summarized. Section VII dis- cusses the reasons of the failure. Section VIII provides a summary and the conclusion of the study. Finally, refer- ences are given at the end. 2. Goals of Telecom ACT 1996 The Telecommunication Act of 1996 was a second major restructuring of the US Telecommunication sector after 1934 Act. Congress took radical steps to restructure US Telecommunication markets by passing the Act [16]. Three major goals of the Act can be stated as follows. •The prime goal of the Act was the creation of com- petition in the local telephony market. •The second goal of the Act was to increase invest- ment in local infrastructure by creating co mpetition. •The third goal was to achieve of universal service. Strategy of the Act The Act tries to create competition in three ways. (i) Reselling (ii) Unbundled Access (iii) New Entry (full facilities based) Reselling eases entry in the retail business, by requir-  84 Kashif Azim Janjua, Sahibzada Ahmed Noor and Shahzada Alamgir Khan Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM ing Incumbent Local Exchange Carriers (ILECs) to sell services to new entrants at wholesale prices. Such entry is limited only to the retailing side of the market. The most significant means of entry is through leasing of unbun- dled network elements from incumbents. It mandates in- terconnection, unbundling and non discrimination to boost competition and reduce artificial barriers to entry. Competitors can enter easily by purchasing Unbundled Network Element (UNEs) or by constructing their own infrastructure. In this way they can compete component by component and service by service. The Act imposes conditions to ensure de facto monop- oly power is not exported to vertically related markets. Thus the Act tries to ensure the competition is created in local market before allowing RBOCs to enter in the long distance market. The Act allows RBOCs to enter in the long distance market segment only after fulfilling a list of 14 requirements. 3. Analysis of the Present Market Situation To judge the success of Telecom Act 1996, it is necessary to find the success of different strategies used. To analyze the effects of these strategies, following questions are analyzed here. 1. What portion of the market is captured by Competi- tive Local Exchange Carriers (CLECs)? 2. What technologies are used by CLECs? 3. How an average consumer is affected by the Act? First question will provide the status of competition in local market. Second question will decide about the suc- cess of approaches used b y FCC to introduce competition. Third question will throw light whether subscribers have gained benefits of the rapid technological advancements. Data used in this analysis is primarily taken from FCC. 3.1. Market Share Figure 1 [16] shows the number of ILEC and CLEC end- user switched access lines from December 1999 to De- cember 2005. CLECs provided only 31.5 million (or 18%) of the approximately 215 million nationwide switched access lines in service to end user customers at the end of December 2005. Figure 3 [16] is the graphical representa- tion of percentage CLEC share over the years. The in- crease in lines shows the slow pace of competition in the market. It is also evident from this figure that major share of market is still held by ILECs. Figure 2 [17] shows the market share of CLECs and ILECs. This is based on ILEC and CLEC share of local service revenues from 1998 to 2003. CLECs could in- crease their share of revenue to only 15% of the total revenue. This is really a small portio n as compared to the revenue of ILECs. Figure 4 [16] gives an account of the popularity of three different techniques used by FCC to attain competi- tion. As evident that owned capacity by CLECs has been almost the same, thus showing that no serious investment in infrastructure has been made. Resale has decreased dramatically where as Unbundled Network Element (UNEs) purchase has increased a lot. This show with the time negotiations between companies about unbundled access is easing out making it most successful approach. Also resale has not gained popularity. End User Lines (in Millions) 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 200 Dec 1999 Jun 2000 Dec 2000 Jun 2001 Dec 2001 Jun 2002 Dec 2002 Jun 2003 Dec 2003 Jun 2004 Dec 2004 Jun 2005 Dec 2005 Jun 2006 Dec 2006 Year Lines (in Millions) ILEC Li nesCLEC lines Figure 1. CLEC Vs. ILEC Share S h a r e o f R e v e n u e 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 19981999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Year %age ILEC ShareCLEC share Figure 2. CLEC Vs. ILEC Share of Revenue CLEC Sh are 0. 0 5. 0 10. 0 15. 0 20. 0 25. 0 Dec 1999 Jun 2000 Dec 2000 Ju n 2001 Dec 2001 Jun 2002 Dec 2002 Ju n 2003 Dec 2003 Jun 2004 Dec 2004 Ju n 2005 Dec 2005 Jun 2006 Dec 2006 Year %a g e CLEC Share Figure 3. Percentage CLEC share of lines 3.2. Comparison of technologies Figure 5 [16] shows that FCC’s approach of enticing co- axial companies has also failed as only 16% of CLEC’s  A Critical Evaluation of Telecommunication Act 1996 Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM 85 network is coaxial based. Coaxial cable has failed as a substitute to copper pair in local loop. Figure 6 [16] show the distribution of lines of CLECs and ILECs. In the be- ginning CLECs only concentrated on business lines but now slowly they are moving their direction towards the bigger portion of the society, that is, the residential sub- scriber. Slowly their percentage share of residential sub- scribers has increased. Types of li nes of CLECs 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 Dec 1999 Jun 2000 Dec 2000 Jun 2001 Dec 2001 Jun 2002 Dec 2002 Jun 2003 Dec 2003 Jun 2004 Dec 2004 Jun 2005 Dec 2005 Ju n 2006 Dec 2006 Year %age Resold UNEs CLEC-Owned Figure 4. Types of lines of CLECs Figure 5. Percentage of coaxial supported lines 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% %a g e Dec 1999 Jun 2000 Dec 2000 Jun 2001 Dec 2001 Jun 2002 Dec 2002 Jun 2003 Dec 2003 Jun 2004 Dec 2004 Jun 2005 Dec 2005 Jun 2006 Dec 2006 Years %age of Residential customers ILECs CLECs Figure 6. Percentage of residential customers 3.3. Consumer expenditure Figure7 [17] presents an average household spending on telecom services. As evident that the expenditure of local services has increased where as the international service expenditure has decreased quite a bit. In international market there is quite a bit competition g iving the benefits directly to consumers. Av er age M ont hl y Charges 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 1995 199619971998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 Year $ Local ChargesLong Distance ChargesTotal Figure 7. Average Monthly Charges 4. Fallouts of the ACT Following fallouts of the Act are evident from today’s market. Vertical reintegration The Act allowed local telephone companies to offer long distance service but to provide such service in their area they have to fulfill their commitment of creating competition in the area. The Act included a checklist of 14 points for RBOCs to fulfill before their entry into In ter LATA services [18]. The opportunity of allowing RBOCs an entry in long distance market was not a successful strategy. This allowed RBOCs to again enter in the long distance markets. Problems arise, when a telecommunica- tion carrier with monopoly or near monopoly power in the provision of a particular facility also offers a competi- tive service that is dependent upon the use of the monop- oly facility. These problems are cross subsidization and discrimination. The Act allowed RBOCs to monopolize using these methods. They acted in the same direction. The result was a wave of mergers and acquisitions. Mergers and Acquisitions Mergers especially vertical ones are enemies of the competition as they kill the concept of co-o peration. Ver- tical Mergers can squeeze other companies and create monopoly in the market. Earlier, in the absence of entry in the local exchange market as envisioned by the Act, the major long distance companies bought companies that gave them some access to the local market. For example, MCI merged with WorldCom, which had just merged with Brooks Fiber and MFS, which in turn also own some infrastructure in local exchange markets. AT&T unveiled an ambitious strategy of reaching con- sumer homes by using cable TV wires for the last mile. With this purpose in mind, AT&T bought TCI and in April 1999 AT&T outbid Comcast and acquired Me- diaOne, the cable spin-off of US West. AT&T also ac- quired TCG, which owned local exchange infrastructure Coaxial Cable suppoted lines (%age) 0.0 5.0 10.0 15.0 20.0 25.0 Dec 1999 Jun 2000 Dec 2000 Jun 2001Dec 2001 Jun 2002 Dec 2002 Jun 2003Dec 2003 Jun 2004 Dec 2004 Jun 2005Dec 2005 Jun 2006Dec 2006 Year %a g e Perc ent Coaxial Cabl e  86 Kashif Azim Janjua, Sahibzada Ahmed Noor and Shahzada Alamgir Khan Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM that reached business customers. All such mergers and acquisitions tarnished the image of a fully competitive telecom market. Re-monopolization by RBOCs Attempts by the RBOCs to maximize their foothold in- clude SBC’s acquisition of Pacific Bell and Ameritech, and Bell Atlantic’s merger with NYNEX. SBC also bought Southern New England Telephone (SNET). Bell Atlantic has merged with GTE, creating Verizon. Thus, the 8 large local exchange carriers of 1996 (7 RBOCs and GTE) are reduced to only 4: Verizon, Bell South, SBC, and US West. US West recently merged with Qwest. SBC first bought AT&T in 2005 and then recently it has merged with Bell South leaving just three major companies in local telephony. Twenty years after the government broke up the long- standing MA Bell monopoly, the re-monopolization of telecommunication is almost done. This is the worst con- sequence of the Act. Telecom market is facing the same position as it faced twenty years back. The companies have regained their vertical structure and are edging the whole market towards a monopolistic state. 5. Section 271 Checklist In return for opening their markets to competition, the Telecom Act allowed RBOCs to enter interstate long- distance markets, which had been prohibited since the 1984 breakup of AT&T. The Telecom Act’s Section 271 provided a 14-point checklist incumbent RBOCs must satisfy before they are allowed into interstate markets. The checklist consisted of specific market-opening ac- tions, such as providing non-discriminatory access to UNEs. The approval process requires that RBOCs apply for 271 approval on a state-by-state basis, and begins by receiving state-regulator certification that section 271’s checklist has been satisfied. Following are the major points of the checklist. 1. The BOC must allow requesting carriers to physi- cally link their communications networks to its network for the mutual exchange of traffic. To do so, the BOC must permit carriers to use any available method of inter- connection at any available point in the BOC’s network. Interconnection between networks must be equal in qual- ity whether the interconnection is between the BOC and an affiliate, or the BOC and competing local carrier. 2. The BOC must provide a connection to network ele- ments at any technically feasible point under rates, terms, and conditions that are just, reasonable and nondiscrimi- natory. Non-discriminatory access to OSS (systems, data- bases, and personnel) is required to facilitate nondis- criminatory access to network elements. 3. The BOC must show that competitors can obtain ac- cess to poles, ducts, conduits, and rights-of-way within reasonable time frames and on reasonable terms and con- ditions, with a minimum of administrative costs, and con- sistent with fair and efficient practices. 4. The BOC must demonstrate that it has a concrete and specific legal obligation to furnish loops on an un- bundled basis and that it is currently doing so in the quan- tities that competitors reasonably demand and at an ac- ceptable level of quality. 5. The BOC must provide competitors with the trans- mission links on an unbundled basis that are dedicated to the use of that competitor as well as links that are shared with other carriers, including the BOC. 6. The BOC must provide Unbundled Local Switching to the competitors. 7. The BOC must provide competing carriers with ac- curate and nondiscriminatory access to 911 and E911 so that competitors’ customers are able to reach emergency assistance, directory assistance and operator services. 8. White pages listings for customers of different carri- ers are comparable, in terms of accuracy and reliability, notwithstanding the identity of the customer’s telephone service provider. 9. The BOC must provide other carriers with the same access to new NXX codes within an area code that the BOC enjoys. 10. The BOC must demonstrate that it provides com- petitors with the same access to the call-related databases and associated signaling that it provides itself. 11. The BOC must demonstrate that it provides number portability to competing carriers in a reasonable time frame. 12. The BOC must establish that customers of another carrier are able to dial the same number of digits to make a local telephone call. In addition, the dialing delay ex- perienced by the customers of another carrier should not be greater than that experienced by customers of the BOC. 13. The BOC must compensate other local carriers for the cost of transporting and terminating a local call from the BOC. Alternatively, the BOC and competing carrier may enter into an arrangement whereby neither of the two carriers charges the other for terminating local traffic that originates on the other carrier’s network. 14. The BOC must offer other carriers all of its retail services at wholesale rates without unreasonable or dis- criminatory condition or limitations such that other carri- ers may resell those services to an end user. Role of FCC  A Critical Evaluation of Telecommunication Act 1996 Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM 87 FCC approved the first 271 application, Verizon’s New York application, in December 1999, nearly four years after the Act’s passage. As July 1, 2002, the FCC had approved 271 applica- tions in Arkansas, Connecticut, Georgia, Kansas, Louisi- ana, Massachusetts, Maine, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Texas and Vermont. The FCC was in the process of reviewing ap- plications from Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, New Hampshire and Delaware. RBOCs received 271 approvals for all of their states by December 2003 [19]. There was a vast difference between what the fourteen- point checklist says FCC should do, and what it allows the FCC to do. The opinion of FCC was that the Commis- sion must apply the terms of the competitive checklist strictly as they were written, as the FCC did not write the law. Still FCC’s Local Competition Order contains hun- dreds of pages of binding law on the meaning of 11 of the 14 checklist items. For example the Local Competition Order contains no less than 20 paragraphs discussing what it means to provide unbundled local loops. The whole situation was severely troubled by the extent of de- tail in which FCC had immersed itself in administering the fourteen-point checklist. The Commission vastly ex- panded the fourteen-point statutory checklist to include a plethora of new sub elements. All this happened because Section 271 permitted an incredible degree of FCC mi- cromanagement. Role of RBOCs RBOCs always insisted that each rulemaking and deci- sion added to or altered the compliance requirements, sometimes very significantly. The continually evolving nature of these requirements was a major problem. The costs associated with meeting these requirements consti- tuted a significant barrier to RBOC entry into the inter- LATA market. This was like a never receding finish line for their entry into the long distance market. RBOCs refused to accept the performance standards and performance penalties that the Department of Justice identified as necessary to ensure non-discrimination on an ongoing basis and continued a legal battle. Once RBOCs got the permissions they started mergers and acquisitions. Eight large carriers of 1996 have reduced to just four now. Role of AT&T and other long distance companies The long distance carriers – AT&T, MCI and Sprint were thought to be the most likely entrants into local ser- vices but they were very slow to move. They used this slow progress to argue against any attempt by RBOBs to enter the long distance market, and they did this success- fully in every case filed. FCC refused to approve RBOCs applications for inter LATA services on the grounds that they have failed to comply with some aspects of the re- quired competitive checklist. Long distance companies used every tactic to stop RBOCs from entering the lucrative long distance services. They did not make any crucial investments in local infra- structure just to stop RBOCs from entering their market. 6. Results Following are the results of section III, IV and V. 1. Since the approval of Act in 1996, CLECs have not been able to increase their share of the market. They have tried to enter the market but still their part is limited and most of the network is still held by ILECs. 2. The market of local telephony has moved to little bit of competition but at very slow pace. 3. RBOCs still hold a monopoly or near monopoly po- sitions in their areas. 4. As evident from graph 4, percentage of CLEC owned infrastructure based lines remains the same, thus showing that CLECs have not made any crucial invest- ment. 5. RBOCs have extended their monopoly to the long distance markets. 6. There is a wave of mergers and acquisitions as a re- sult of Telecom Act distorting the whole market. 7. RBOCs have re monopolized and re grouped. 8. Residential Area is mostly neglected by CLECs. 9. Coaxial cable has failed as substitute fo r twisted p air based infrastructure. 10. The subscribers are unable to receive the benefits of technological advances due to unregulated monopoli- zation in local market. 11. Congress intended to write a pro competitive, de- regulatory law but did not do so. Telecom Act’s propo- nents did not understand the realities of the telecom mar- ket and the incentives of the multibillion-dollar corpora- tions in it. A law that seemed simple and spare when Congress wrote it became impossibly complicated and over regulatory when the FCC implemented it. 12. Each of the14 points on the checklist became a point of contention, friction, and delay. 13. This list helped the long distance carriers and clearly slowed entry of RBOCs into long distance market for a number of years. Once RBOCs got entry, they jeop- ardized the whole market by mergers and acquisitions. We can say that The telecommunication Act 1996 has failed to achieve its goal of achieving full competition in all markets even  88 Kashif Azim Janjua, Sahibzada Ahmed Noor and Shahzada Alamgir Khan Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM after 10 years. It has been able to induce very little com- petition especially in the last mile at very slow pace. RBOCs still hold a monopoly or near monopoly positions in their areas. As a result of mergers and acquisitions they have re monopolized and vertically re integrated. FCC, RBOCs and long distance companies all were responsible for the failure of the 14-point checklist. Hence it is hard for the subscribers to receive the full advantages of tech- nology developments. In the next section we shall take a detailed look at the reasons of failure of telecom Act. 7. Reasons for Failure Following are the major reasons for failure of Telecom Act 1996. Local loop is a natural monopoly Telecom Act failed because it took the wrong direction. The intentions were right to provide fruits of technology development to the consumers but the approach was wrong. In local loop duplication does not bring additional util- ity whereas additional cost is tremendous. The local loop is a natural monopoly just like water companies. Monop- oly in local telephony segment is very difficult to break due to high economies of scale. The basic error was the breaking of local monopoly as even after 10 years, Bell companies are still monopolies in their regions. In most of the regions they have consoli- dated their positions. Investments in local loop is not required There is no need of more investment in local loop as it will only create duplication. In 1996 about 95% of houses had the access to tele- phone service [20]. As the access rate is so high, creating competition simply means duplication of infrastructure or reselling of the same facilities. Most of the subscribers don’t need more than one line in their houses. Hence the Act has created unregulated monopolies in the local Telephony market. Unregulated local monopolies are worse than regulated monopolies as they pose a threat for numerous information and commu- nication technology markets that might otherwise be deemed to be effectively competitive. UNE pricing with TELRIC The Act required the incumbent operators to provide competitors access to parts of their network. FCC was assigned the responsibility to decide exactly which parts to be offered. From here the problem started. FCC made a comprehensive list of UNEs including switches, transport lines and local loop. The list included all the facilities of incumbent operator to be provided to the competitors at price set by regulators. The Act called the price to be just and reasonable. FCC calculated the prices using TELRIC. TELRIC is a forward looking cost- ing method which includes the incremental cost resulting from adding or subtracting a specific network element. TELRIC introduced low prices for UNEs. The availability of UNEs from incumbent carriers at low regulated prices distorted the market. It created a ‘make vs. buy’ trade-off for competitors. They decided to lease vital equipment rather than making the expensive and risky investments in making their own infrastructure [21]. This created a second best sort of competition with competition among the firms sharing the same infrastruc- ture at artificially low rates ordered by regulators. This also hindered the new investment as it discour- aged incumbent carriers from investing in their networks since benefits have to be shared with rivals. Overall in- cumbent investment had been $15 billion less than it would be without these rules [22]. Least regulatory control The regulatory control over the monopoly has been re- leased in the Act. The Act envisioned a totally competi- tive market and did not provide regulatory controls in case competition is not healthy enough. Unregulated con- trol of the local loop bottleneck has posed a severe risk for the telecom sector. Without regulation, the monopoly pricing always re- sults in substantial deadweight losses and may block the emergence of innovative services. Thus absent regulation of the ILEC bottleneck has been a th reat to consumer sur- plus and overall efficiency as deadweight losses are likely to be large. The abuse of market power has adversely im- pacted competition all along the value chain of informa- tion technology that depends on PSTN. Universal Service The most disastrous and useless section of the Act were those that dealt with the universal service. Congress gave FCC more power to create havoc in the market in the name of social justice and expansion of so- cial welfare. The policymakers failed to eliminate or make radical reforms in subsidization methods used for universal service. Current subsidization policies redistribute money in highly inefficient manner to provide cheap local service to all. These subsidies flow from long distance to local users, from business to residential users and from urban to rural users. This mechanism was created to favor AT&T to strengthen its monopoly power. But in competi- tion these subsidies have destroyed the market structure  A Critical Evaluation of Telecommunication Act 1996 Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM 89 by discouraging market entry since it is always difficult to compete with subsidized firms [23-26]. Self contradiction On one side the Act advocates new investment but on the other side it allows UNE pricing by TELRIC which discourages both incumbents and new comers to invest. On one side the Act calls for competition but on th e other side it promotes universal service which itself promotes monopolization. 8. Conclusion The Telecommunication Act 1996 was considered as a break through in the telecom market. It has failed to achieve its goals. Vertical reintegratio n, mergers, acquisi- tions and re monopolization are major fallouts of the Act. Section 271 also proved to be regulatory mistake over the last 10 years. There are multiple reasons of this failure. Monopoly breaking, UNE pricing and universal service are some of the reasons. As a result RBOCs have con- solidated their monopoly positions in most of the areas. Rapid developments in telecommunication now demand innovation in regulatory regime. REFERENCES [1] Samuelson A. Paul, Nordhaus D. William (1995). “Economics.” McGRAW HILL Inc., pp. 154. [2] Pindyck S. Robert , Rubinfeld L. Daniel (1998). “Microeconomics.” Prentice Hall International Inc., pp. 353. [3] Varian R. Hal (1992). “Intermediate Microeconom- ics – A modern Approach.” W.W. Norton & Com- pany, pp. 430. [4] Woroch A. Glenn (2002). “Local Network Competi- tion.” Handbook of Telecommunication Economics, Elsvier, 2002. [5] Bomsel Olivier & Blanc G.L. (1999). “System growth in the US telecom industry: Analysis of the technical, industrial and regulatory process in the US telecom industry.”Advanced Workshop in Regu- lation and Competition, Newport, USA, May 26-28, 1999. [6] http://www.fcc.gov/Bureau s/OSEC/library/legislativ e_histories/47.pdf [7] http://www.fcc.gov/Bureau s/OSEC/library/legislativ e_histories/40.pdf [8] Goldstein, Fred R. (2005). “The great telecom melt- down.” Artech House, Inc., pp. 20. [9] AT&T. “Milestones in AT&T History.” Available at http://www.corp.att.com/h istory/milestones.html [10] AT&T. “Brief History: The Bell System.” Available at http://www.corp.att.com/history/history3.html [11] Nicholas Economides (1997). “The Telecommunica- tions Act of 1996 and its Impact.” The Annual Tele- communications Policy Conference, Tokyo, Japan, December 4, 1997. [12] AT&T. “A Brief History: Post Divestiture.” Availa- ble at http://www.corp.att.com/history/history4.html [13] Teece D. (1995). “Telecommunication in Transition: Unbundling, reintegration and competition.” Center for research in Management, University of Califor- nia, Berkeley. [14] John R. Richard (2006). “Postal Networks and American Telecommunications.” XIV History Con- gress, Helsinki Finland, 2006 Session 107. [15] Congress (1996). “Telecommunications Act of 1996, Pub. LA. No. 104-104, 110 Stat. 56 (1996).” Avail- able at http://www.fcc.gov/Reports/tcom1996.pdf [16] FCC, Industry Analysis and Technology Division, Wireline Competition Bureau (2007). “Local Tele- phoneCompetition: Status as of December 31, 2005.” available at http://hraunfoss.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/ DOC-279231A1.pdf [17] FCC, Industry Analysis and Technology Division, Wireline Competition Bureau (2007). Trends in Telephone Service. Available at http://hraunfoss.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/ DOC-270407A1.pdf [18] Congress (1996). “Section 271(C)(2)(B), Telecom- munications Act of 1996, Pub. LA. No. 104-104, 110 Stat. 56(1996).”Available at http://www.fcc.gov/Reports/tcom1996.pdf [19] www.fcc.gov/Bureaus/Common_Carrier/inregion_a pplications [20] FCC, Industry Analysis and Technology Division, Wireline Competition Bureau(2006). “Telephone subscribership in united states.” Available at http://hraunfoss.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/ DOC-268003A1.pdf [21] Randolph J. May & Larry F. Darby (2002). “Com- ments of the Progress and Freedom Foundation Be- fore the Federal Communications Commission, Re- view of the Section 251 Unbundling Obligations of Incumbent Local Exchange Carriers. CC Dkt. No. 01-338” (filed April 5, 2002). [22] Eisenach A. Jeffrey, Lenard M. Thomas (2003). “Telecom Deregulation and the Economy: The Im- pact of “UNE-P” on Jobs, Investment and Growth.” The Progress and Freedom Foundation Release 10.3. [23] Grandall W. Robert, Waverman L. (2000). “Who Pays for Universal Service.” Brookings Institution Press, pp. 47. [24] Turner S. Derek (2006). “Universal Service Reforms & Convergence: USF policy for the 21st century.” 34th research conference on communication, Infor- mation and Internet Policy (TPRC) (Sept. 29 – Oct. 1, 2006) Arlington, VA.  90 Kashif Azim Janjua, Sahibzada Ahmed Noor and Shahzada Alamgir Khan Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM [25] Rosenberg Edwin, Perez-Chavolla Lilia, Liu Jing (2006). “Universal Service.” The National Regula- tory Research Institute. [26] Gifford L. Raymond, Peters M. Adam, Riordan H. Michael (2005). “Digital Age Communication Act : Proposal of the universal service working group, re- lease 2.0.” The Progress and Freedom Foundation. AUTHORS’ BIOGRAPHIES Kashif Azim Janjua, is currently doing his Ph.D. in management sciences and engineering from beijing university of posts and telecommunications, Beijing, China. He did his masters in computer engineering and bachelors in electrical engineering from university of engineering and technology, Lahore, Pakistan. His research interests include firm or- ganization theories, transaction cost economics, vertical integration and regulation. Sahibzada Ahmed Noor, is currently doing his masters in telecommunication and information and systems from the beijing university of posts and telecommunications Beijing, China. He did his bachelors in software eng from shenyang instituite of chemical engineering, Shenyang, China. His research interests include mobile networks, MIPv6 and data processing using Microsoft tools. Shahzada Alamgir Khan, is currently doing his Ph.D. in management sciences and engineering from beijing univer- sity of posts and telecommunications, Beijing, China. He did his masters in electononis engineering and bachelors in electrical engineering from university of engineering and technology, Taxila, Pakistan. Research interests include uni- versal service issues in telecommunication and history of telecommunication. |