Advances in Applied Sociology 2014. Vol.4, No.1, 5-14 Published Online January 201 4 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/aasoci) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2014.41002 The Evaluation of Domestic Violence: The Case of Zonguldak Tülin G. İçli1, Mehmet Pekkaya2, Hanifi Sever3 1Hacettepe University, Sociology Department, Ankara, Turkey 2Bülent Ecevit Universtiy, Business Administration Department, Zonguldak, Turkey 3Bülent Ecevit University, Phd C., Inspector, Turkish National Police, Zonguldak, Turkey Email: ticli@hacettepe.edu.tr, mehpekkaya@gmail.com, hanifisever@yahoo.com Received November 26th, 2013; revised December 26th, 2013; accepted January 5th, 2014 Copyright © 2014 Tülin G. İçli et a l. This is an open access article distrib uted under the C reative Commons At- tribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved f or SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Tülin G. İçli et al. All Copyright © 2 014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. Domestic violence in general terms, refers to incidents in which one of the family members violently acts against to another member. It may occur between spouses, between parents and children, between child- ren or between children and grandparents. However, the most frequent type of domestic violence is be- tween male and female partners. Since “family” is the fundamental element of society, the reasons of do- mestic violence must be well-understood in order to implement correct precautions against it. The aim of this study is to provide an evaluation of domestic violence in the city of Zonguldak. In this respect, some important previous studies, and some remarkable statistics on Zonguldak are reviewed firstly. Upon that, domestic violence cases in Zonguldak city between 2009 and 2011 are investigated retrospectively. Keywords: Domestic Violence; Emotional Violence; Sexual Violence; Physical Violence Introduction Based on the societal structure, the structure of families may vary. However, it is common that disputes within family mem- bers are solved again within the family. One of the most signifi- cant problems experienced in contemporary “family” is domes- tic violence. Today, the news on domestic violence has become more frequent in media. Although most incidents of domestic violence remain secret in a family (İçli, 1994: p.7), some of them yet lead to courts. Domestic violence refers to incidents in which one of the family members violently acts against to another member. Do- mestic violence may occur between spouses, between parents and children, between children or between children and grand- parents. However, the most frequent type of domestic violence is between male and female partners. Domestic violence mostly occurs as one of the four types, namely physical, psychological, economic and sexual type. The person who experiences domestic violence is mostly pushed, punched, kicked and attacked with several devices, leading to physical pain (Kyriacou, et al., 1999: p.1892). In addition, the person may experience threats, assaults, insults and humiliation. Spouses may use the sexual intercourse as a way of punish- ment. In addition to these well-established types of domestic violence, there are other kinds. For instance, married women who want to work may not be given permission to do so by their husbands. Such instances are called economic violence. Based on the data reported by the Turkish Statistics Institu- tion (TUIK) (2011b), it can be stated that 42.9% of the women living in the Western Black Sea region including the provinces of Bartın, Karabük and Zonguldak have experienced domestic violence. This region is in the fourth rank in Turkey by means of domestic violence against women. For this reason, the statistics and the inferences of this study are very important for further researches on domestic violence that may focus on similar demographic properties as of Zon- guldak’s. The aim of this study is to provide an evaluation of domestic violence in the city of Zonguldak. The following parts of the study contain data from some important previous studies, and some remarkable statistics on Zonguldak and then, domestic violence cases in Zonguldak city between 2009 and 2011 are investigated retrospectively. Studies on Domestic Violence Violence occurs in different forms in the family context. It may occur between spouse, between siblings or between par- ents and offsprings. Such cases may lead to deaths. Parents mostly kick, push, sock, or abuse their children. With regard to domestic violence between siblings, it is found that 80% of the children at the age group of 3 - 17 expe- rience at least one violence incident perpetrated by their sibl- ings (Ritzer, 1990: p. 188). There are studies that emphasize the fact that violence is a learned act (Ayan, 2007; Bilican Gökkaya, 2011). It is further argued that children learn violence and it becomes a lasting behavior in the adulthood (İçli, 1994; İçli, 2007). Domestic violence between parents and children is very common. Such violence incidents mostly occur between ado- lescents and their parents in the form of verbal insults or even physical attacks. In a study, it is found that 43% of the male children and 41% of the female children had an experience of attacks against older family members (Mahoney & Donelly, OPEN ACCESS 5 T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. 2000). In another study, it is found that 14% of fathers and 20.2% of mothers experienced violence perpetrated by their children. It can be stated that women experience the most frequent cases of domestic violence. There are various accounts of this fact, including socio-psychological and sociological approaches. İçli (1994) states that women are subjects of domestic violence because they try to maintain marriage after the first incidence of violence. The fact that desperate women contribute to the continuation of domestic violence has been related with gender-role based socialization (İçli, 2007; Ritzer, 1990: pp. 190-192). After so- cializing based on gender-roles, women think that they can not avoid domestic violence or that they have limited chance to avoid it when they face with violence (İçli, 1994: p. 10). The other reason for frequent experience of women the do- mestic violence is about economical disadvantages of women. Since they have no or little economic sources to continue their life independently, they feel themselves helpless in the face of domestic violence. It is certain that such factors are much more dominant in patriarch societies (Ann Hoff, 1990: p. 32). The rate of women who are seriously wounded due to do- mestic violence is 9%, while it is 22% in less serious wounding cases (Wi lt & Olson, 1996). Furthermore, women are murdered by their spouses in one-third of homicide cases in the US (Kel- lermann & Mercy, 1992). Smith et al. (1998) reports that of 4.739 homicide incidents including women in the US in 1994, 28.4% of them were perpetrated by male spouses. Moreover; 17.337 homicide cases in the US were perpetrated by female spouses (Maguire & Pastore, 1996). It is estimated that only 15% of domestic violence in the United Kingdom are reported to police. 27% of women are estimated to have domestic vi- olence experience in their life (Mooney, 1993). 97 women were killed by their spouses in the UK and Wales in 1996 and it forms 45% of all homicide cases involving women (Mayhew, 1996). In Pakistan, a total of 370 homicide cases involving women were reported during the first six-month of 1992, and 50% of them were related to domestic violence (Bhatti et al., 2011). Catalano (2007) states that 95.7% of women are subject to domestic violence perpetrated by their sposes. In another study in UK, it is found that 28% of women among 1007 married couples experince physical violence (Painter, 1991: p. 44). In a similar vein, Mooney (1993) found that 30% of 430 women in northern London had the experience of physical violence, in- cluding pushing, shaking or stabbing. In Turkey, a total of 1.070 married women were interviewed in Ankara, İstanbul and İzmir. It was found that 21.2% of the participants experienced physical violence perpetrated by their spouses. The most fre- quently stated reason for violence is “economical problems”. 78% of the participants reported that they prefer to keep quiet and endure the violence (İçli, 1994). Domestic violence mostly affects those women with limited economical resources (Davis, 1999; Gelles, 1997; Hetling & Zhang, 2010; Lloyd & Taluc, 1999; Logan et al., 2007; Renzet- ti, 2009; Tolman & Raphael, 2000; Williams & Mickelson, 2004). Particularly, limitations on accessing the sources are serious disadvantages for the women without any income or with lower-levels of income (Williams & Mickelson, 2004). It is estimated that nearly 4.4 million women are abused by their spouses in the US every year (Plichta, 1996; Tjaden & Thoennes, 1998). Although the women from all socio-eco- nomic levels are subject to domestic violence (Wiehe, 1998), domestic violence is much more frequent among those women with lower levels of income (Hotaling & Sugarman, 1990). A study concerning the economic status of women experienced domestic violence from 2001 to 2005 states that 12.7% of these women have less than the annual income of $7,500 and that only 2% of them have more than the annual income of $50,000 (Catalano, 2007). Another study suggests that 44% of the women who are subject to domestic violence do not have any job or any (Erbek at al., 2004). As stated earlier, domestic violence against women may happen in the form of sexual violence. In a study involving 613 Japanese women experienced domestic violence, it is found that 57% of the participants are subject to physical, psychological and sexual violence (Yoshihama & Sorenson, 1994). Another study carried out in Mexico found that 52% of the women ex- perienced physical violence also experience sexual violence (Granados-Shiroma, 1996). In a Nicaraguan study, it is found that only five out of 100 battled women did not come across sexual violence (Ellsberg at al., 2000). Another study in Turkey dealt with the reports of married couples applied for Marriage Counselling Center in İstanbul. The rates of women who reported domestic violence and sexual violence are as follows: 29.3% of them reported that they occa- sionally experience sexual violence; 2% of them reported that they frequently experience sexual violence and 4% of them reported that their spouses force them to make love (Erbek et al., 2004: p.200). The findings of a study carried out in Çanakkale show that the sexual needs of 10.9% of the women with domes- tic violence history are neglected. 9.8% of them reported forced sexual intercourse. 7.9% of them reported that sexual perfor- mance is underestimated. 4.9% of them states that sexual inter- course is avoided and it is used as a punishment. 2.7% of them reported rape by their spouse (Tanrıverdi & Şıpkın, 2008). In another study in Aydın, it is found that 9.2% of women re- ported sexual abuse (Karaçam et al., 2006). Kyriacou et al. (1999) found that those women with domestic violence experience who applied for hospitals in the US form the first category. Their socio-economic and behavioral charac- teristics of women from the age group of 18-64 were analyzed. The most frequently stated reasons for domestic violence are found to be the perpetrators’ use of alcohol, drug use, long- period unemployment and the women’s meeting with ex- spouses. The mean age of the women is found to be 32. The educational background of the women with domestic violence history is as follows: 35.2% university education; 29.7% high school education; 33.2% less than high school education. The distribution of their annual incomes is as follows: 83.2% less than annual income of $30,000. The rate of women who are alcohol addicted is found to be 22.7%. The mean age of perpe- trators is found to be 34. The educational level of perpetrators is found to be as follows; 21.1% university education; 30.5% high school education and 39.5% less than high school education. Their employment status is as follows: 49.2% full-employment, 9% part-time jobs and 9% unemployment. 63.7% of the perpe- trators are addicted to alcohol, while 36.7% are addicted to drugs. In a Slovenian study involving 829 subjects (506 women and 323 men), it is found that 20.5% of men and 79.5% of women are subject to domestic violence. Psychological violence was experienced by 19.2% of men and 80.8% of women. Physical violence was experienced 22.4% of men and 77.6% of women. OPEN ACCESS 6 T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. Violence is found to be experienced mostly by the age group of 18 - 35 (29.1%). 22% of those who experienced domestic vi- olence have no child. 26% of them have one, 36.2% two and 15.7% three or more children. Interestingly, it is also found that perpetrators are other family members than husbands in 15.4% of the incidents. The use of alcohol and unemployment are found to be important factors in domestic violence (Selic et al., 2011). In another study carried out in the US, it is found that 753 women with domestic violence history are of the age group 18 - 54. More specifically, 28% of them were younger than 25, 46% of them between 25 and 34, and 26% of them older than 35. 66% women have one child. Of those who reported psycholog- ical violence, 55% were threatened to be battled. 55.4% of those who experienced physical violence were stabbed and pushed. 34% of them were slapped and kicked. 19.3 of them reported forced sexual intercourse (Tolman & Rosen, 2001). In the study carried out in Çanakkale involving 366 women, it is found that 51.6% of women with domestic violence history are graduates of primary school. It is also found that 36.9% of perpetrators are also graduates of primary education. The rate of women with children is found to be 89.1%. The incidents of physical violence were pushing (29.2%), throwing objects (28.4%) and slapping (25.7%) (Tanrıverdi & Şıpkın, 2008). Another study was carried out in Ankara with a sample of 370 women who are older than 15 and have domestic violence history. It is found that 51.4% of women are of the age group 30 - 49, 23.8% are illiterate, 62.7% are graduates of primary school and 95% are housewives without any income. It is fur- ther found that 72.9% perpetrator spouses are graduates of pri- mary school and 89.7% of them are employed (Efe & Ayaz, 2010). In another study, it is found that 34.2% of 202 women with domestic violence history have university education, 30.8% of them have the annual income of $50,000 and 55% of them are younger than 40 (Gielen et al., 2000). Ellsberg et al. (2000) found that 60% of the women in the sample experienced more than one incident of domestic vi- olence in the last twelve months. On the other hand, the rate of those who experienced more than six domestic incidents in the same period is 20%. Separation and divorce are two significant factors in domes- tic violence (Morley & Mullender, 1994). In a study carried out in the Northern Ireland, it is found that 56% of the married couples with single child divorce due to domestic violence (Evason, 1982: p. 17). Browne (1987) argues that one-third of the divorced women had experience of domestic violence. Some studies deal with the characteristics of children who either witness domestic violence or experience it. Such children are in risk groups (Herrera & McCloskey, 2001; Finkelhor et al., 2005; Kitzmann et al., 2003). They are reported to have aggres- sion and anti-social personality disorder (Widom, 2000). They more frequently exhibit the externalizing behavior of aggres- siveness towards peers in contrast to those who did not witness domestic violence (Raviv et al., 2001). Those female children who witnessed domestic violence are reported to exhibit with- drawn behavior such as depression and anxiety disorder (O’Keefe, 1994, 1995). On the other hand, in a study in Sivas, 54% of the children reported domestic violence perpetrated by their father and 46% by their mother. The educational level of their mother is mostly primary education (56%) and 89% are house wife. In regard to perpetrator fathers, it is found that half of them have high school or university education (50%). They are mostly worker or civil servant (46%) (Ayan, 2007). It is argued that those parents who perpetrate domestic violence against their children have childhood domestic violence history (Kaymak Özmen, 2004; Vahip, 2002). Patriarch systems are regarded as one of the most significant factors leading to domestic violence. Such systems allow men to control and punish their spouses (Dobash & Dobash, 1984; Ptacek, 1997; Hearn, 1998). On the other hand, it is argued that women perpetrate domestic violence in order to avoid potential physical and psychological violence perpetrated by their male partners (Cascardi & Vivian, 1995; Dobash & Dobash, 1994). Data on Demography of the City of Zonguldak Table 1 presents the demographic data of Turkey and Zon- guldak. As seen in Table 1, each year the population of Turkey increases by nearly 1 million and the rate of the population increase is 1.43% between 2007 and 2011. However, the popu- lation of Zonguldak decreases and it becomes more apparent in 2011. Furthermore, the number of women in Zonguldak is higher than that of men. Table 2 provides the demographical characteristics of people living in Zonguldak in 2011. As seen in the Table 2, the rela- tion between age groups and gender is statistically significant (chi square = 1742.56, p valu e = 0.000). As it can be noted, the number of men over the age of 34 is higher than women, but the number of women below the age of 34 is higher. On the other hand, overall number of women is higher than that of men and the mean age of women is also higher. Table 3 presents the data on marriage and divorce in Zon- guldak from 2005 to 2010. As can be seen, there is relation between marige/divorce and year (chi square = 3042.39, p val- ue = 0.000). The number of marriages with respect to divorces made a peak in 2006 and made a decrease especially in 2010. As a mean for six years, marage is 5.46 times higher than that of divorce. Table 4 presents the data on the reasons for divorces and duration of marriages in Zonguldak in 2010. In regard to the reasons for divorce in Zonguldak in 2010 (Table 4), incompa- tibility is the most frequent reason stated by nearly all subjects. It is interesting that the reasons for divorce do not include adul- tery, attempt against life, cruelty or serious insult. The mean marriage duration for those couple divorced is ten years. Table 5 provides the data on the age of marriage for men and women in Zonguldak from 2005 to 2010. In this five-year pe- riod, the mean age of marriage for women increased from 22.5 to 23, and that for men also increased from 25 to 26. Table 6 shows the data on educational levels of women in Zonguldak in 2009. It is seen that 78.7% of women have less than high school education. Table 7 presents the percentages of domestic violence expe- rienced by women in Zonguldak based on their age and educa- tional level. It is seen that older the women, higher the rate of domestic violence. Therefore, the age group that mostly expe- riences domestic violence is interestingly that of 45 - 59 with the rate of 45.4%. In terms of educational background, it is seen that 52.2% of the illiterate women experience domestic violence. This rate among those with basic education is 39.9%. 25% of the women with high school or higher education experience domestic vi- olence. These findings may get inferences that higher the edu- OPEN ACCESS 7  T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. Table 1. Comparison of Turkey and Zonguldak in terms of population from 2007 to 2011. Turkey Zonguldak Men Wo men Men Wo men 2007 35,376,533 35,209,723 302,827 313,063 2008 35,901,154 35,615,946 304,997 314,154 2009 36,462,470 36,098,842 306,075 313,737 2010 37,043,182 36,679,806 307,550 312,153 2011 37,532,954 37,191,315 302,370 310,036 Annual mean difference 539,105 495,398 −114 −757 (%) 1.49 1.38 −0.03 −0.24 Source: TUIK, 2011. Table 2. Population of Z onguldak in 2011 in terms of gende r and age groups. Age groups Male (M) Female (F) Total Differences based on gender (=K − E) 0 - 4 20,904 19,850 40,754 −1054 5 - 9 20,783 19,636 40,419 −1147 10 - 14 23,111 21,856 44,967 −1255 15 - 19 22,419 22,243 44,662 −176 20 - 24 22,549 23,132 45,681 583 25 - 29 25,408 24,505 49,913 −903 30 - 34 26,431 25,950 52,381 −481 35 - 39 23,438 23,656 47,094 218 40 - 44 20,664 21,714 42,378 1050 45 - 49 20,846 22,744 43,590 1898 50 - 54 20,454 21,251 41,705 797 55 - 59 18,977 18,892 37,869 −85 60 - 64 13,354 13,802 27,156 448 65 - 69 8349 9544 17,893 1195 70 - 74 6202 8057 14,259 1855 75 - 79 5098 6770 11,868 1672 80 - 84 2614 4445 7059 1831 85 - 89 661 1590 2251 929 +90 108 399 507 291 Mean age: 33.87 35.46 34.67 Mean difference: 403.47 Source: TUIK, 2011. Table 3. Data on marriage and divorce in Z onguldak from 2005 to 2010. Years 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Mean Marriages (M) 6,103 6,494 6,094 5,960 6,192 5,033 5,979 Divorce (D) 1,101 1,007 1,106 1,176 1,173 1,023 1,097 Ratio of M/D 5.54 6.45 5.51 5.07 5.28 4.92 5.46 Source: TUIK, 2011. Table 4. Data on the reasons for divorces and duration of marriages in Zongul- dak in 2010. Reasons for divor ce Numb er Duration of marriage Numb e r Adultery 1 Less than a year 52 Attempt against life, cruelty or serious insult 1 One year 81 Two years 71 Infamous crime or dishonorable conduct - Three years 78 Willful desertion 3 Four years 74 Insanity - Five years 62 Incompatibility 997 Six to ten years 233 Other 7 Eleven to fifteen years 153 Unknown 14 More than 16 years 219 Total 1023 Total 1023 Source: TUIK, 2011. Table 5. Age of marriage for men (M) and women (F) in Zonguldak from 2005 to 2010. Age/gender 2005 2006 2007 F M F M F M Mean age 23.3 26.6 25.7 28.8 24.5 27.7 Age of marriage 22.5 25.0 22.7 25.3 22.8 25.4 Age/gender 2008 2009 2010 F M F M F M Mean age 24.3 27.5 29.3 32.4 26.2 29.6 Age of marriage 23.0 25.6 23.2 25.9 23.4 26.1 Source: TUIK, 2011. cational levels of women, lower the rate of domestic violence. Methodology Based on the data reported by the Turkish Statistics Institu- tion (TUIK) (2011b), it can be stated that 42.9% of the women living in the western Black Sea region including the provinces of Bartın, Karabük and Zonguldak have the experience of do- mestic violence. This region is at the fourth rank in terms of domestic violence experience of women. Erbek et al. (2004, p.199) argue that the rate of women from Western Black Sea Region (the cities of Zonguldak, Bartın and Karabük) who applied EDAM (The Center of Marriage Advi- sory) as a result of their experience of domestic violence is the highest rate (28%) when compared with the rest of Turkey. The data of the study are collected from the domestic vi- olence cases occurred in the districts of Bağlık, Tepebaşı, Mithatpaşa, Meşrutiyet, Yayla, Çınartepe, İnağzı, Asma, Yeni- mahalle, Yeşil, Dilaver, and Baştarla in Zonguldak from 1 Jan- uary 2009 to 31 December 2011. The number of cases investi- gated is 326. The data are given in tables and cross tables that are calculated for statistical tests by using SPSS 18.0 version program. OPEN ACCESS 8  T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. Table 6. Data on educational levels of women in Zonguldak in 2009. Educational level Primary education and l ess High school Undergraduate education Post-graduate Doctorate Total Percentage (%) 78.7 15.5 5.5 0.2 0.1 100 Source: TUIK, 2011b. Table 7. Percentage of domestic violence experienced by women in Zonguldak based on their age and educational level. Age group Domestic violence rate (%) Educational level Domestic violence rate (%) 15 - 24 31.9 Illiterate 52.2 25 - 34 36.6 Basic education 39.9 35 - 44 45 - 59 39.7 45.4 High school education and hig her 25 Source: TUIK, 2011b. Results Findings According to Victims The years of the cases are as follows: 34% of cases occurred in 2011, 37.1% in 2010 and 28.8% in 2009. All these cases were reported to the official authorities. The half of the married participants (50.5%) has been married for ten years or less. The rate of participants who experienced domestic violence in the first three years of the marriage is 25.8%. Of the married couples, 13.2% have no child. 27.6% have one child and 45.4% two children. As seen in Table 8, 43.3% the participants are from the age group of 30 - 39 and 30.1% of them of 19 - 29. The youngest of the victims is 16 years-old, whereas the eldest one is 82 years old. 81.3% of the participants have a history of domestic violence, whereas, 18.7% have no history of violence. Table 9 shows that mostly women are the target of the do- mestic violence (90.2%). Only 6.7% of them are men. The term “children” in the table refers to those younger than 18 years old. 67.8% of the victims have primary education or less. Only 4% of them have university education. Majority of the victims are house wife (76.7%). There are also civil servants (3.1%) and workers (15.3%). Majority of the victims (79.4%) have no income. Victims are mostly subject to physical violence (68.1%). They also expe- rience emotional violence (24.2%) and sexual violence (7.7%). The victims reported several reasons for domestic violence, including the use of alcohol by the spouse (20.6%), divorce suit (14.4%) and adultery (13.5%). Additionally, 35% of them re- ported that ordinary discussions lead to domestic violence. Findings According to Perpetrators As seen in Table 10, majority of the perpetrators are from the age group of 30 - 39 (52.5%); 19.3% of them from the age group of 40 - 49. The youngest perpetrator is 15 years old, while the eldest one is 82 years-old. The majority of the perpetrators have secondary education (75.2%). Nearly half of the perpetrators are coal mining work- ers (45.7%). However, the major income source can be stated as mining for the people living in Zonguldak, known as the most popular coalfield of Turkey. So, this finding is not sur- Table 8. Age groups of victims and Percentage of the previous domestic vi- olence history. Age group n % Violence History n % 11 - 18 7 2.1 Experienced violence 265 81.3 19 - 29 98 30.1 30 - 39 141 43.3 No violence experience 61 18.7 40 - 49 52 16 Older than 50 28 8.6 Total 326 100 Total 326 100 prising. The rate of the perpetrators who are unemployed is 12.6%. The rate of the perpetrators who have no income is 12.6%. Adultery is given as the highest frequent reason for domestic violence by perpetrators (23.9%). Another frequently reported reason for domestic violence is divorce suit (22.7%). Therefore, nearly half of the cases occurred due to adultery and divorce suit (46.6%). Domestic violence occurred mostly in the form of slapping and punching (53.7%). Additionally, attacks with knives and ax also occurred with the rat e of 4.3% . As a result of domestic violence, 20% of the victims were wounded, requiring more serious medical intervention. The rate of those experienced psychological trauma as a result of do- mestic violence is 23.6% (Table 11). At the significance level of 0.05, it is statisctically significant that types of domestic violence experienced related with the victims with income and without income. Namely, as the rea- sons of “the use of alcohol and psychological problems” and “economics problems” are more common for victims without income than victims with income, but the reasons of “adultery” and “divorce suit” are more common for victims with income than victims without income. The victims without income re- ported that the frequent reason for domestic violence is either the use of alcohol or economic problems. The frequent reasons for domestic violence by the victims with income are adultery and divorce suit (Table 12). Of 326 victims experienced domestic violence in the period of 2009-2011, one-fifth (65 persons) were treated in intensive care or medically observed in clinics. Of those who treated in OPEN ACCESS 9  T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. Table 9. Victims. Vi ct i ms n % Women 294 90.2 Children 1 0.3 Spouses 22 6.7 Sons/daughters 9 2.8 Total 326 100 Reasons for Domestic Violence n % The use of al cohol by t he spouse 67 20.6 Economic problems 41 12.6 Incompatibility 114 35 Adultery of the spouse 44 13.5 Mental illness of the spouse 13 4 Divorce suit 47 14.4 Total 326 100 Violence type n % Physical violence 222 68.1 Emotional violence 79 24.2 Sexual violence 25 7.7 Total 326 100 Income n % Yes 67 20.6 No 259 79.4 Total 326 100 Job n % House wife 250 76.7 Civil servant 10 3.1 Worker 50 15.3 Self-employed 13 4 Retired 3 0.9 Total 326 100 Education n % Illiterate 15 4.6 Basic education 206 63.2 High school 92 28.2 University 13 4 Total 326 100 intensive care unit, 38 had experienced physical violence, while 25 had sexual violence. Nearly one-fourth of the 326 cases (77 persons) reported psychological trauma and their wish to have psychiatric treatment as a result of domestic violence. It is seen that domestic violence has negative effects on the individuals’ health and psychological well-being. Furthermore, 43.55 of the victims (142 persons) needed for a long-time treatment or intensive care due to traumas they expe- rienced (Table 13). The relation between types of violence and the reaction of Table 10. Age of perpetrators. Age group n % 11 - 18 5 1.5 19 - 29 47 14.4 30 - 39 171 52.5 40 - 49 63 19.3 Older than 50 40 12.3 Total 326 100 Income n % Yes 285 87.4 No 41 12.6 Total 326 100 Job n % Unemployed 41 12.6 Civil servant 16 4.9 Worker 149 45.7 Retired 36 11.0 Self-employed 84 25.8 Total 326 100 Education al l evel n % Illiterate 5 1.5 Secondary school education 245 75.2 High school education 62 19.0 University education 13 4.0 Post-graduate education 1 0.3 Total 326 100 Reasons for Domestic Violence n % The use of al cohol 51 15.6 Economic problems 45 13.8 Incompatibility 68 20.9 Adultery 78 23.9 Mental illness 10 3.1 Divorce suit 74 22.7 Total 326 100 perpetrators is statistically significant at a level of 0.01. It is seen in Table 14 that it is much more likely for perpetrators of physical violence to escape after the incident. The possibility of arrest of perpetrators o psychological or sexual violence is much higher. Since the results of physical violence are much more subject to legal punishment, they tend to escape. However, for the perpetrators of psychological and sexual violence such cases are much less. The relationship between duration of marriage and the reac- tion of perpetrators is found to be statistically significant. Those who relatively married for a short time are arrested. However, those who married long time ago tend to escape after the inci- dent (Table 15). It is found that the relationship between duration of marriage OPEN ACCESS 10  T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. Table 11. Types of violence. group n % n % Slapping and punching 175 53.7 Simple medical Intervention 184 56.4 Kicking 37 11.3 Attacks with knife 10 3.1 Requires more serious medical intervention 65 20.0 Attacks with ax 4 1.2 Profanity and insults 76 23.3 Rape and forced sexual intercourse 24 7.4 Psychological trau ma 77 23.6 Total 326 100 Total 326 100 Table 12. Reasons for domestic violence based on income status of victims. Victims with income Victims without income n % n % P-value The use of alcohol and psychological problems 12 17.9 68 26.2 11.47 0.43 Economic problems 4 6 37 14.3 Routine family disputes 24 35.8 90 34.7 Adultery 14 20.9 30 11.6 Divorce suit 13 19.4 34 13.1 Table 13. Medical intervention for the victims based on the types of domestic violence. Physical violence Psychological violence Sexual violence Total n % n % n % n % Simple medical intervention 183 82.43 1 1.27 - - 184 56.44 Clinical observation and intensive care 38 17.12 2 2.53 25 100 65 19.94 Psychological trau ma 1 0.45 76 96.2 - - 77 23.62 Total 222 100 79 100 25 100 326 100 Table 14. The relationship between types of violence and perpetrators reaction. Perpetrator escaped Perpetrators arrested n % n % P value Physical violence 47 85.45 175 64.58 9.177 0.010 Psychological violence 6 10.91 73 26.94 Sexual violence 2 3.64 23 8.49 Total 55 100 271 100 and the types of domestic violence is statistically significant (Table 16). Longer the duration of marriage, lower the rate of physical and sexual violence, but higher the rate of psychologi- cal violence. Therefore, in the early years of marriage, disputes Table 15. Relation between duration of marriage and perpetrators reaction. Duration of marriage Perpetrator escaped Perpetrator arrested n % n % P value 1 - 7 years 16 29.1 112 41.3 6.625 0.036 8 - 16 years 17 30.9 95 35.1 +17 years 22 40.0 64 23.6 Total 55 100 271 100 Table 16. Relationship between duration of marriage and the types of domestic violence. Duration of marriage Physical violence violence Sexual violence n % n % n % P value 1 - 7 years 100 45.0 22 27.9 6 39.3 11.98 0.018 8 - 16 years 65 29.3 34 43.0 13 34.4 +17 years 57 25.7 23 29.1 6 26.4 Total 222 100 79 100 25 100 are solved through physical power. During the first seven years of the marriage and during the advanced mature period (seven- teen years and longer) the rate of psychological violence is lower. However, it is very high (nearly 50%) during the mature period of marriage (8 - 16 years). The reason for the use of physical power to solve disputes during the early years of marriage seems to be related with the inexperience of spouses. Later in the marriage, psychological violence is much more frequently used to solve disputes. It may be a result of the fact that spouses recognizes that they could not solve problems through physical power. The children may be also influential in this regard. The rate of violence decreases significantly during the advanced mature period of marriage. Because spouses become mature, children become older and spouses need themselves much as a result of their ages. The duration of marriage leads to the changes in the reasons for domestic violence (Table 17). The relationship between duration of marriage and the types of domestic violence is found to be statistically significant at a level of 0.01. For the couples who are married for 17 or more years, the reasons for domestic violence are the use of alcohol and related psycholog- ical problems (42.5%). Economic problems are found to be primary reason for do- mestic violence among the couples married for the period of 1 - 7 years (41.5%). The longer the duration of marriage, lower the effects of economic problems on domestic violence. These couples also experience domestic violence due to daily family disputes (49.1%). Such disputes may arise since they get mar- ried before well knowing each other. Adultery is much more common reason for domestic vi- olence for the couples married for the period of 1 - 7 years (40.9%). The effects of adultery on domestic violence decrease when they are based on the duration of marriage. The rate of divorce increases in the eighth and sixteenth years of the marriage (36.2%). The subjects are found to have wanted to divorce and prosecuted for divorce. As stated earlier, OPEN ACCESS 11  T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. Table 17. Relationship between du ration o f marriage and the reasons f o r domestic violence. marriage The use of alcohol and problems Economic problems Routine family disputes Adultery n % n % n % n % n % 1 - 7 years 22 27.5 17 41.5 56 49.1 18 40.9 15 31.9 8 - 16 years 24 30.0 13 31.7 42 36.8 16 36.4 17 36.2 +17 years 34 42.5 11 26.8 16 14.0 10 22.7 15 31.9 Total 80 100 41 100 114 100 44 100 47 100 (P value) 22.43 (0.004) divorce suit is one of the reasons for domestic violence. Discussion Studies show that when the victims are getting older, the possibility of experiencing domestic violence increases. The mean age of women in the study by Kyriacou et al. (1999) is 32, while that in the study by Vahip & Doğanavşargil (2006) is 38. Selic et al. (2011) argued that the rate of violence decreases when the couples become older. The age group which most frequently comes across domestic violence is found to be that of 18 - 35 with the rate of 29.1. In a study carried out in the US, the age group of victims is found to be as follows: 28% young- er than, 46% is from the age group of 25 - 34 and 26% older than 35 (Tolman & Rosen, 2001). In another study carried out in Ankara, it is found that 51.4% of the victims belong to the age group of 30 - 49 (Efe & Ayaz, 2010). Gielen et al. (2000) found that 55% of the victims are younger than 40. In the cur- rent study, 43.3% the participants are from the age group of 30 - 39 and 30.1% of 19 - 29. This finding is consistent with the data of TUIK. In regard to educational background of women who are vic- tims of domestic violence there are different findings. For in- stance, Kyriacou et al. (1999) found the followings; 35.2 of university education, 29.7% high school and 33.2% less than high school. Gielen et al. (2000)’s findings in this regard are as follows: 34.2% university education. In another study, it is found that 35.2% of the victims are university graduates, 29.7% high school graduates and 33.2 of them have less than high school education (Selic et al., 2011). Tanrıverdi & Şıpkın (2008) found that 51.6% of the victims are primary school graduates. Efe & Ayaz (2010) found that 23.8% of the victims are illiterate, while 62.7% are primary school graduates. In the current study, majority of the victims are primary school graduates (63.2%) and 28.4% of them are high school graduates. The findings on the educational background of the victims show similarities with those of the studies carried out in Turkey, but inconsistent with those of the international studies. Catalano (2007) states that 95.7% of the women experience domestic violence perpetrated by their spouse. The rate of such women is found to be 28% in the study by Painter (1991, p.44), 30% in the study by Mooney (1993) and 21.2% in the study by İçli (1994). Selic et al. (2011) found that physical violence tar- gets 22.4% of men and 77.6 of women and that psychological violence targets mostly women (19.2% of men, 80.8% of women). In the current study, it is found that 68.1% of victims experience physical violence perpetrated by their spouse, while 24.2% of them experience psychological violence. The rate of women who experienced sexual violence and abuse has been reported as follows; 57% in the study in Japan by Yoshihama and Sorenson (1994), 52% in the study in Me x- ico by Granados-Shiroma (1996), 19.3% in the study in the US (Tolman & Rosen, 2001); 95% in Nicaragua study (Ellsberg et al., 2000); 35.3% in the study in Istanbul (Erbek et al., 2004, p.200); 36.2% in the study in Çanakkale (Tanrıverdi & Şıpkın, 2008) and 9.2% in the study in Aydın (Karaçam et al., 2006). In the current study, the rate of women experienced sexual vi- olence is 7.7% that is much lower. Unlike other reports (Bhatti et al., 2011; Kellermann & Mercy, 1992; Maguire & Pastore, 1996; Mayhew, 1996; Mooney, 1993; Smith et al., 1998), there was no killing of the victim in the period analyzed in the study. Research suggests that employment and income are two sig- nificant factors in the incidents of domestic violence in which one of the spouses are killed (Dugan et al., 1999). There are also other findings, stating that domestic violence has much more hazardous effects for the women with no or little income and economic sources (Catalano, 2007; Davis, 1999; Erbek et al., 2004; Gelles, 1997; Hetling & Zhang, 2010; Lloyd & Taluc, 1999; Logan et al., 2007; Renzetti, 2009; Tolman & Raphael, 2000; Williams & Mickelson, 2004). The current finding that majority of the victims have no income (79.4%) is consistent with those of the previous studies. Kyriacou et al. (1999) argue that primary reasons for domes- tic violence are the use of alcohol, drug use, continuous or re- cent unemployment and meeting with ex-spouses. Selic et al. (2011) state that the use of alcohol and unemployment are two crucial factors leading to domestic violence. Similar to previous studies, the women experiencing domestic violence stated the use of alcohol (20.6%), divorce suit (14.4%), adultery (13.5%) and economic problems (12.6%) as the factors resulting in do- mestic violence. Kyriacou et al. (1999) found that 63.7% of the perpetrators are alcohol-addicted, while 36.7% drug-addicted. In the current study, 15.6% of the perpetrators reported that they implement violence due to their addiction to alcohol. The other reason reported by the perpetrators is the suspicion of adultery (23.9%). Divorce suit was also reported as a reason for domestic vi- olence by the perpetrators (22.7%). On the other hand, in the current study, the use of alcohol is found to be a significant factor in domestic violence during the later stages of the mar- riage. The age range of the women is mostly that of 19 - 39 (30.1% (19 - 29 age group) and 43.3% (30 - 39 age group)). The age range of perpetrators is mostly that of 30 - 49 (52.5% (30 - 39 age group) and 19.3% (40 - 49 age group)). The educational background of the perpetrators is similar to that of the victims. One-fourth of the perpetrators are found to have lower levels of education (75.2%). Kyriac ou et al. (1999) found in relation to e mployment status of the perpetrators that 49.2% have full-time employment, 9% part-time employment, 9% are continuously unemployed, 16.8% are unemployed for a long time and 13.3% are recently unemployed. In the current study, only 12.6% of the perpetra- tors are unemployed and that nearly half of them are workers (45.7%). However, given that the major income source for the people living in Zonguldak is coal mines, this finding is not surprising. OPEN ACCESS 12  T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. Tolman & Rosen (2001) argued that 55% were threatened to be battled. 55.4% of those who experienced physical violence were stabbed and pushed. 34% of them were slapped and kicked. 19.3% of them reported forced sexual intercourse. In another study, the most frequent cases of physical violence occurred in the form of pushing forcefully (29.2%), throwing an object (28.4%) and slapping (25.7%) (Tanrıverdi & Şıpkın, 2008). Vahip & Doğanavşargil (2006) found that 88.7% of women experienced physical violence in the form of pushing, kicking and slapping and that 22.6% of them cannot do daily activities due to their wounds. In the current study, it is also found that one of two women experienced physical violence in the form of slapping or punching (53.7%). The rate of those who experienced psychological violence in the form of insults and profanity is 23.3%. The rate of women experiencing sexual violence is found to be 7.4%. There are also attacks with vari- ous objects such as axe, knife and other cutting devices with the rate of 4.3%. The rate of the victims that required more than a simple medical intervention is found to be 19.9%. The rate of those victims who experienced psychological trauma and wanted to have psychiatric treatment is found to be 23.6%. Conclusion Domestic violence is the most important problem for society which must be understood completely. Moreover, governments should take a serious sanction to protect victims. Although motives, types and frequency of domestic violence vary from country to country, it is a common social problem. Domestic violence has four common types such as physical, psychological, sexual and economic type. The most frequent incidents of domestic violence target women and children. The vast majority of women experience domestic violence perpetrated by their spouses. As it is known to be the most common type of domestic violence, physical violence is the main problem for spouses. However, the rates of sexual and emotional violence should not be ignored. Use of alcohol and unemployment are two crucial factors leading to domestic violence. Unfortunately, we found impor- tant evidence about these problems in this study. The age of victims is mostly 20 or older. The peak point of the victims is the age group of 30 - 39. It suggests that victims keep quiet when they face violence, leading to continuous form of the violence. The reason for the women’s such reactions is mostly related with their economical status. Since mostly they have n o income, they are dependent upon their spouses for economic sources. Women also believe that their spouse will stop domes- tic violence at some point in the future. The educational background and age of the perpetrators are similar to that of the victims. The perpetrators are found to have lower levels of education, that is, lower educated spouses are potential danger for victims. Domestic violence may result in serious wounding cases as well as serious psychological trauma. In most cases, perpetra- tors attack the victims with knives or other cutting devices. REFERENCES Ann Hoff, L. (1990). Battered woman as survivors. New York: Rout- ledge Pub. Ayan, S. (2007). Aile içinde şiddete uğrayan çocuklarin saldırganlık eğilimleri. Anadolu Psikiyatri Dergisi, 8, 206-214. Bhatti, N., Jamali, M. B., & Phu lpoto, N. N. (2011). Domestic violence against women: A case study of district Jacobabad, Sindh Pakistan. Asian Social Science, 7, 146-162. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v7n12p146 Bilican Gökkaya, V. (2011). Türkiye’de kadına yönelik ekonomik şiddet. Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi, 12, 101-112. Browne, A. (1987). When battered women kill. New York: The Free Press. Cascardi, M., & Vivian, D. (1995). Context for specific episodes of marital violence: Gender and severity of violence differences. Jour- nal of Family Violence, 10, 265-293. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02110993 Catalano, S. (2007). Intimate partner violence in the United States. Washington DC: US Department of Justice. http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=1000 Davis, M. (1999). The economics of abuse: How violence perpetuates women’s poverty. In R. Brandwein (Eds.), Battered women, children, and welfare reform: The ties that bind (pp. 17-30). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. Dobash, R. E., & Dobash, R. P. (1984). The nature and antecedents of violent events. British Journal of Cri minology, 24, 269-288. Dugan, L., Daniel N., & Richard R. (1999). Explaining the decline in intimate partner homicide: The effects of changing domesticity, women’s status, and domestic violence resources. Ho micide Studies, 3, 187-214. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1088767999003003001 Efe, Ş. Y., & Ayaz, S. (2010). Kadına yönelik aile İçi şiddet ve kadınların aile İçi şiddete bakışı. Anadolu Psikiya tri Dergisi, 11, 23- 39. Ellsberg, M. C., Pena, R., Herrera, A., Liljestrand, J., & Winkvist, A. (2000). Candies in hell: women’s experience of violence in Nicara- gua. Social Science and Medicine, 51, 1595-1610. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00056-3 Erbek, E., Eradamlar, N., Beştepe, E., Akar, H., & Alpkan, L. (2004). Kadına yönelik fiziksel ve cinsel şiddet: Üç grup evli çiftte kar- şılaştırmalı bir çalışma. Düşünen Adam, 17, 196-204. Evason, E. (1982). Hidden violence: Battered women in northern Irel- and. Belfast: Farset Co-operative Press. Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R. K., Turner H. A., & Hamby, S. L. (2005). Measuring poly-victimization usin g t he Juv enile Victimization Ques- tionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29, 1297-1312. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.06.005 Gelles, R. J. (1997). Intimate violence in families (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Gielen, A. C., O’Campo, P. J., Campbell, J. C., Schollenberger, J., Woods, A. B., Jones, A. S., Dienemann , J. A., Kub, J., & Wynne, E. C. (2000), Women’s opinions about do mestic violence screening and mandatory reporting. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 19, 279-285. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00234-8 Granados-Shiroma, M. (1996). Salud reproductive violence contra la mujer: Reproductive hea lth a nd vio lence aga ins t women: An ana lysis from a gender perceptive. Asociación Mexicana de Población, Con- sejo Estatal de Población, Nuevo León, El Colegio de México. Hearn, J. (1998). The violence of men. London: Sage. Herrera, V. M., & McCloskey, L. A. (2001). Gender dif ferences in the risk for delinquency among youth exposed to family violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25, 1037-1051. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00255-1 Hetling, A., & Zhang, H. (2010 ). Domestic violence, p ov erty and social services: Does location matter? Social Science Quarterly, 91, 1144- 1163. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00725.x Hotalling, G. T., & Sugarman, D. B. (19 90). A risk marker analysis of assaulted wives. Journal of Family Violence, 5, 1-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00979135 İçli, T. G. (1994). Aile içi şiddet: Ankara İstanbul ve İzmir örneği. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Dergisi, 11, 7-20. İçli, T. G. (2007 ). Kriminoloji. Ankara: Seçkin Yayınları. Karaçam, Z., Çalışır, H., Dündar, E., Altuntaş, F., & Avcı, H. C. (2006). Evli kadınların aile içi şiddet görmelerini etkileyen faktörler ve kadınların şiddete ilişkin bazı özellikleri. Ege Üniversitesi Hem- şirelik Yüksek Okulu Dergisi, 22, 71-88. Kaymak Özmen, S. (2004). Aile içinde öfke ve saldırganlığın yansı- OPEN ACCESS 13  T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. maları, Ankara Üniversitesi Eğitim Bilimleri Fakültesi Dergisi, 37, 27-39. Kellermann, A. L., & Mercy, J. A. (1992). Men, women, and murder: Gender-specific differences in rates of fatal violence and victimiza- tion. Journal of Trauma, 33, 1-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005373-199207000-00001 Kitzmann, K. M., Gaylord, N. K., Holt A. R., & Kenny, E. D. (2003). Child witnesses to d omestic violence: A Meta-Analy tic review. Jour- nal of Consulting and Clinical P s ychology, 71, 339-352. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.2.339 Kyriacou, D. N., Anglin , D., Taliaf erro, E. , Stone, S ., Tubb , T., Linden , J. A., Muelleman, R., Barton, E., & Kraus, J. F. (1999), Risk factors for injury to women from domestic violence. The New England Journal of Medicine, 341, 1892-1898. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199912163412505 Lloyd, S., & Taluc , N. (199 9). The imp act of recen t partn er violence on women’s capacity to maintain work. Violence Against Women, 5, 370-392. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/10778019922181275 Logan, T. K., Shannon, L., Cole, J., & Swanberg, J. (2007). Partner stalking and implications for women’s employment. Journal of In- terpersonal Violence, 22, 268-291. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260506295380 Mahoney, A., & D on n elly, W. O. (2000). Adolescent-to-parent physical aggression in clinic-referred families: Prevalence and cooccurrence with parent-to-adolescent physical aggression. Victimization of Children and Youth: An Interna tional Research Conferen ce. Durham, NH: Family Research Laboratory, University of New Hampshire. Mayhew, P. (1996). Crime statistics for England and Wales. HMSO: London. Maguire, K., & Pastore, A. L. (1996). Sourcebook of criminal justice statistics 1995. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. Mooney, J. (1993). The hidden figure of domestic violence in North London. London: Islington Council: Morley, R., & Mullender, A. (1994). Preventing domestic violence to woman, police research group crime prevention unit series. Paper No: 48, London: Home Office Police Department. O’Keefe, M. (1994). Linking marital violence, mother-child/father- child aggression, and child behavior problems. Journal of Family Vi- olence, 9, 63-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01531969 O’Keefe, M. (1995). Predictors of child ab use in maritally violen t fa mi- lies. Journal of Inter personal Violence, 10, 3-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/088626095010001001 Painter, K. (1991). Wife rape, Marriage and the Law. Survey Report: Key Findings and Recommendations. Faculty of Economic and So- cial Studies University of Manchester, Department of Social Policy and Social Work. Plichta, S. B. (1996). Violence and abuse: Implications for women’s health. In M. M. Falik, & K. S. Collin s (Eds.), Women’s health: The Commonwealth Fund survey (pp. 237-272). Baltimore: Johns Hop- kins University Press. Ptacek, J. (1997). The tactics and strategies o f men who batter. In A. P. Cardarelli (Ed.), Violence between intimate partners (pp. 104-123). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Raviv, A., Erel , O., Fox, N. A., Leavitt, L. A., Raviv, A., Dar, I., Sha- hinfar, A., & Greenbaum, C. W. (2001). Individual measurement of exposure to everyday violence among elementary schoolchildren across various settings. Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 117- 140. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(200103)29:2<117::AID-JCOP1 009>3.0.CO;2-2 Renzetti, C. M. (2009). Economic stress and domestic violence. Ap- plied Research Foru m, National Online Resource Center on violence against women. http:// www.vawnet.org/category/Main_Doc.php?docid=2187 Ritzer, G. (1990 ). Social Problems. Random House. NewYork. Selic, P., Pesjak, K., & Kersn ik, J. (2011). The prevalence of exposure to domestic violence and th e f actors as so ciated with co -occu rrence of psychological and physical violence exposure: A sample from pri- mary care patients. BMC Public Health, 11, 621-631. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-621 Smith, P. H., Moracco, K. E., & Butts, J. D. (1998). Partner homicide in context: A population-based perspective. Homicide Studies, 2, 400- 421. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1088767998002004004 Tanrıverdi, G., & Şıpkın, S. (2008). Çanakkale'de sağlık ocaklarına başvuran kadınların eğitim durumunun şiddet görme düzeyine etkisi. Fırat Tıp Dergisi, 13, 183-187. Tjaden, P., & Thoennes, N. (1998). Prevalence, incidence, and conse- quences of violence against women: Findings from the national vi- olence against women su rvey. Washington, DC: Natio nal Institute of Justice and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tolman, R., & Raphael, R. (200 0). A review of research on welf are and domestic violence. Journal of Social Issues, 56, 655-682. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00190 Tolman, R., & Rosen, D. (2001). Domestic violence in the lives of woman receiving walfare. Violence against Woman, 7, 141-158. Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu (TUIK). (2011). Marriage and Divorce Sta- Tistics 2010. Ankara: Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu Matbaası. Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu (TUIK). (2011b). Woman in Statistics 2010. Ankara: Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu Matbaası. Widom, C. S. (2000). Childhood victimization: Early adversity, later psychopathology. National Institute of Justice Journal, 1, 2-9. Wiehe, V. R. (1998). Understanding family violence: Treating and preventing partner, child, sibling, and elder abuse. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. Williams, S. L., & Mickelson, K. D. (2004). The nexus of domestic violence and poverty: Resilience in women’s anxiety. Violence against Women, 10, 283-293. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077801203262519 Wilt S., & Olson S. (1996). Prevalence of domestic violence in the United States. Journal of American Medical Women’s Association, 51, 77-82. Yoshihama, M., & Sorenson S. B. (1994). Physical, sexual, and emo- tional abuse by male intimate: Experiences of women in Japan. Vi- olence and Victims, 9, 63-77. Vahip, I. (2002). Evdeki şiddet ve gelişimsel boyutu: Farklı bir açıdan bakış. Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi, 13, 312-319. Vahip, I., & Doğanavşargil, Ö. (2006). Aile içi fiziksel şiddet ve kadın hastalarımız. Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi, 17, 107-114. OPEN ACCESS 14

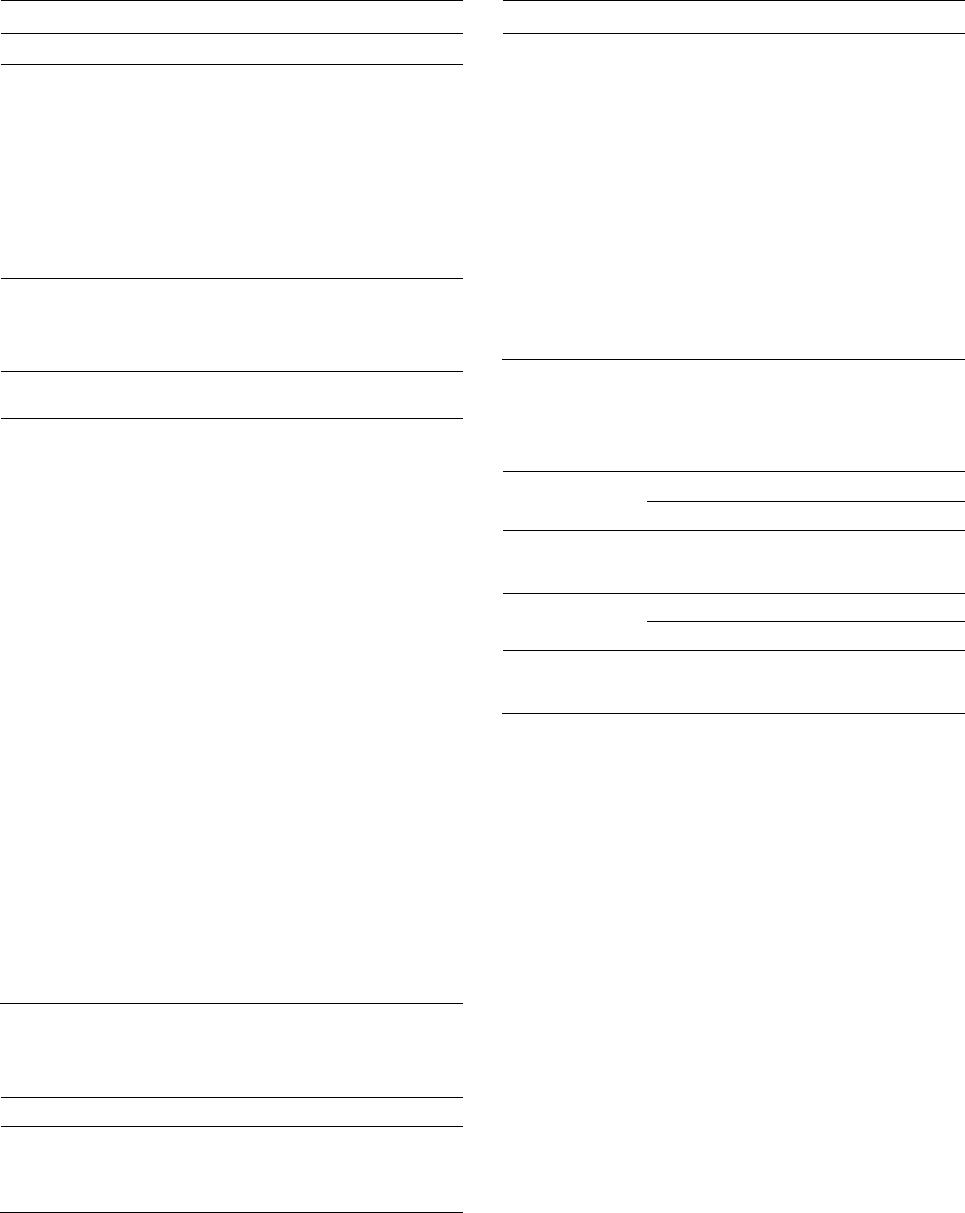

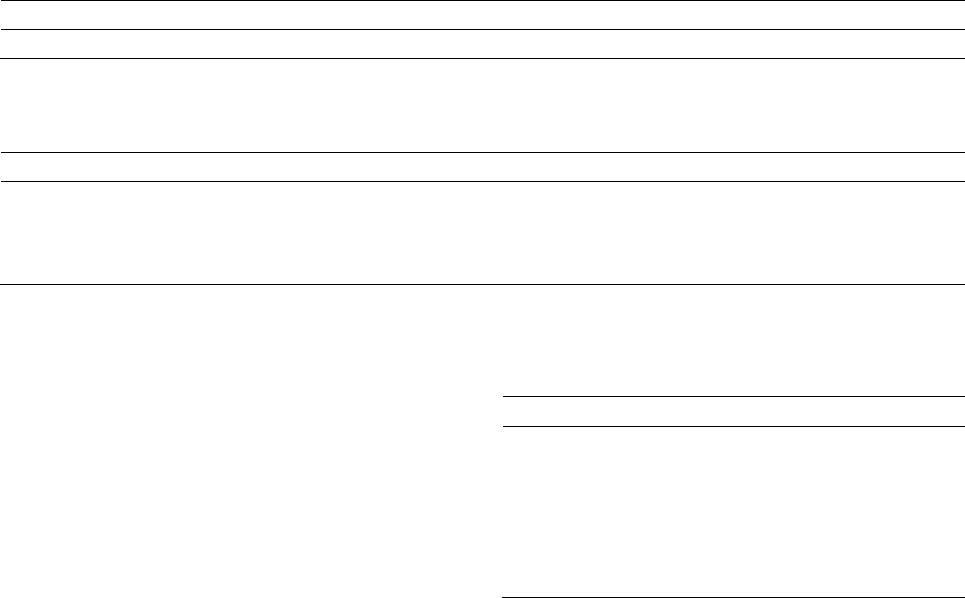

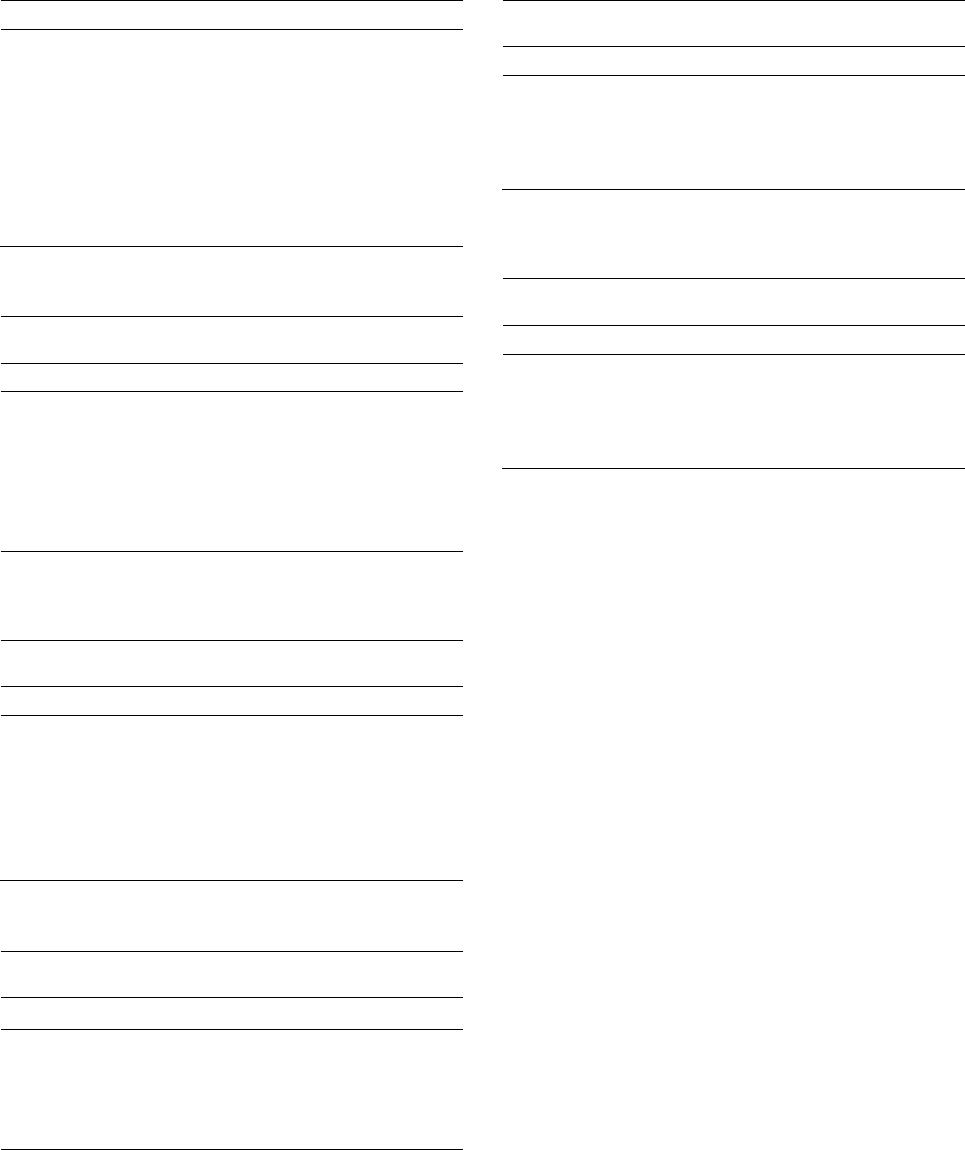

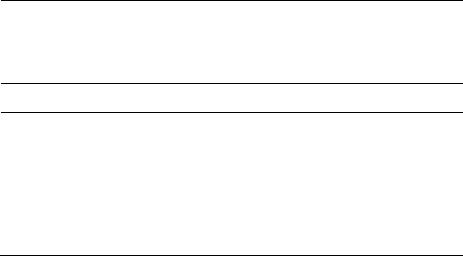

|