Open Access Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2014, 2, 22-28 Published Online February 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jss http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jss.2014.22004 How to cite this paper Cheng, G. and Wong, T.-L. (2014) A Study on Learning Styles and Acceptance of Using Second Life for Learning in a Visual Arts Course. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2, 22-28. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jss.2014.22004 A Study on Learning Styles and Acceptance of Using Second Life for Learning in a Visual Arts Course Gary Cheng1, Tak-Lam Wong2 1Department of Mathematics and Information Technology, The Hong Kong Institute of Education, Hong Kong, China 2Department of Computer Science, Caritas Institute of Higher Education, Hong Kong, China Email: chengks@ied.edu.hk, tlwong@cihe.edu.hk Received October 2013 Abstract This paper reports and discusses on the initial stage of a study aiming to explore the relationship between students’ learning styles and their acceptance of using Second Life (SL) for learning. Par- ticipants in this study involved a small group of undergraduate students (N = 17) taking a Visual Arts course called ‘Digital Imaging’ at a university in Hong Kong. They were asked to create and showcase their own digital artwork in SL. Furthermore, they were also required to present their work and critique peers’ work in SL. Their learning styles were measured by the Index of Learning Styles (ILS), whereas their acceptance of Second Life for learning was evaluated by a questionnaire designed by the author. Preliminary findings of this study reveal that most participants were identified as visual learners (i.e. the ones who prefer to see in graphical/video representation). However, active learners (i.e. the ones who prefer to try something out to see how it works) were found more likely to accept the educational use of SL. Keywords Second Life; Virtual World; Learning Styles; Learner Acceptance 1. Introduction A virtual world is regarded as an online 3-D environment supporting multiple users to communicate and interact with each other in real time [1]. With the advance in 3-D technologies and internetworking capabilities, it is feasible for us to interact with virtual objects, to express ourselves using photo-realistic avatars, and to maintain social connections with other people across different geographical boundaries in the virtual world [2]. There is little doubt that the virtual world has exerted increasing influence over our lives, particularly in digital enter- tainment. The enthusiasm of people who are engaged in the virtual world for fun has prompted educational re- searchers to consider using this technology to enhance student learning and engagement [3].  G. Cheng, T.-L. Wong In recent years, there has been a growing body of literature examining the effectiveness of the virtual world in adding value to student learning across different learning contexts [4-7]. Findings of these studies have illumi- nated the importance of the virtual world in supporting new pedagogical approaches for students to achieve an engaging learning experience. The findings also led us to the present study, in which we focused on addressing a more fundamental question concerning the relationship between students’ learning styles and their acceptance of the virtual world for educational use. 2. Teaching and Learning with Second Life Launched by Linden Lab in 2003, Second Life (SL) is an online, 3-D virtual world that enables users to create their own avatars and interact with others. Despite the existence of other virtual worlds (e.g., Active Worlds, There and Twinity), SL has remained popular with a huge user base over the years [8]. In this study, therefore, SL was selected as the virtual world for use and analysis. SL can potentially support rich interaction, visualisation and contextualisation, authentic content and culture, identity play, immersion, simulation, community presence and content production [3]. Its benefits can be seen in a range of learning contexts, such as promoting argumentative knowledge construction by means of role-playing [6], offering a simulated environment to equip students with professional knowledge and skills [7], using an immersive and interactive approach to deliver online courses to students across different locations [4], and faci- litating experiential learning through interactions and observations in virtual field trips [5]. However, research has reported mixed results regarding students’ acceptance of SL for educational purposes. For example, Vogel and his colleagues [9] have shown that most students perceived SL as an online gaming en- vironment for fun rather than a tool to support serious learning. In contrast, another study [10] has found that students generally expressed positive feelings about using SL as a learning platform. Since learning style is a good predictor of learning preference and attitude towards e-learning [11], the mixed results of previous re- search can likely be accounted for by differences in students’ learning styles, highlighting the need for this study to take learning style into consideration. Specifically, this study sought to answer the following two research questions: 1) what is the relationship be- tween students’ learning styles and their acceptance of using SL for learning? and 2) from teacher’s perspective, what are the benefits and drawbacks of SL that may influence the acceptance of using SL for educational use? Results of this study will provide insights into more effective practice of using SL to promote student learning. 3. Method 3.1. Participants This study took place in a Visual Arts course called ‘Digital Imaging’ offered in 2011/12 at a university in Hong Kong. In the initial stage of this study, seventeen students voluntarily accepted an invitation to participate in this study. Their demographic information was collected by means of a questionnaire and the information is shown in Table 1. 3.2. Learning Styles The Index of Learning Styles (ILS) was employed to identify participants’ learning styles in this study [12]. The ILS is a 44-item, self-report questionnaire that evaluates students’ learning preferences on four dimensions (ac- tive/reflective, sensing/intuitive, visual/verbal and sequential/global). The first dimension (with 11 items) em- phasises on the difference between an active and a reflective way of processing information. Active learners prefer to try something out to see how it works while reflective learners prefer to think about and reflect on it first. The second dimension (with 11 items) distinguishes between a sensing and an intuitive way of perceiving information. Sensing learners prefer to learn facts and concrete data. They tend to be patient with details and good at doing practical work. In contrast, intuitive learners prefer to learn abstract concepts as well as to discov- er possibilities and relationships, so they tend to be more innovative. In the third dimension (with 11 items), learners are characterised according to their preference of receiving information. Visual learners remember best what they see in graphical/video representation (e.g. pictures, diagrams and demonstrations) whereas verbal learners get more out of written or spoken words. The last dimension (with 11 items) concerns two different  G. Cheng, T.-L. Wong Table 1. Demographic information of participants. Demographic Dimension N Percentage Gender Male 6 35.5% Female 11 64.7% Age 18 - 20 3 17.6% 21 - 23 12 70.6% 24 - 26 2 11.8% Enjoyment of Using Computer An Extreme Amount 7 41.2% Very Much 8 47.1% Moderately 2 11.8% A Little 0 0.0% Not At All 0 0.0% ways of progressing towards understanding. Sequential learners prefer to learn in linear and logical steps while global learners tend to learn randomly and in large leaps. Participants were asked to choose the most appropriate option on each item in ILS. Their choices were con- ver t ed into scores for analysis [13]. A score of 1 to 3 on a dimension indicates a fairly well balanced on both sides of that dimension, while a score of 5 to 7 indicates a moderate preference for one side of a dimension and a score of 9 to 11 indicates a very strong preference. 3.3. Students’ Acceptance of SL Twelve items were designed to collect and evaluate students’ acceptance of using SL for learning. Most items were modified from an empirically validated questionnaire for measuring learner satisfaction with e-learning systems [14]. The items focus on four aspects of SL: resources, communication, identity play, and learning sa- tisfaction. They were asked using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly agree” (5) to “strongly disagree” (1). Table 2 lists the items. 3.4. Procedure The ‘Digital Imaging’ course was designed primarily to equip students with: 1) awareness on the physicality of printed materials, 2) proficiency in digital imaging techniques, and 3) the ability to reflect on digital images. It provided students with hands-on opportunities to learn about how to use digital imaging software and SL. To fulfill one of the course requirements, students were asked to create and showcase their own digital artwork in SL. Furthermore, they also needed to present their work and critique peers’ work in SL. Participants were administered the demographic questionnaire and the ILS at the outset of the study. Once they finished their project presentation in SL, they were asked to complete the acceptance questionnaire. Mean- while, a semi-structured interview was conducted with the course instructor in order to identify the benefits and drawbacks of using SL to support learning from teacher’s perspective. 4. Results and Discussion This section presents and analyses the results of students’ learning styles and their acceptance of SL. A correla- tional analysis between the two constructs will also be reported. Subsequent to the quantitative analysis, the qua- litative feedback from course instructor regarding the use of SL for learning will be discussed. 4.1. Learning Styles Table 3 provides a summary of the ILS results. In this study, the most preferred learning style was visual learn- ing (82.4%), followed by sensing learning (76.5%), active learning (58.8%) and sequential learning (58.8%). Although the results may not generalise widely because of the small sample size, they are consistent with those obtained by [15].  G. Cheng, T.-L. Wong Table 2. Items for evaluation of learner acceptance. SL Aspect Item Resources 1. SL offers resources that enrich my knowledge. 2. SL offers resources that attract my attention. 3. SL presents materials in ways that make the course content more understandable. Communication 4. It is advantageous to meet someone in SL compared to meeting them through instant messengers online. 5. It is advantageous to meet someone in SL compared to meeting them using a webcam chat (such as Skype). 6. It is advantageous to meet someone in SL compared to meeting them face to face in the real world. Identity Play 7. SL provides me the opportunity to engage in self-expression through avatar creation and manipulation. 8. Trying out different avatar “looks” in SL can help me explore different possible identities in the real world. 9. SL uses avatar role play to help me overcome social anxiety and shyness. Learning Satisfaction 10. I feel comfortable to use SL. 11. I enjoy the experience of using SL. 12. I am willing to continue using SL for learning in other courses. Table 3. Results of the ILS. ILS Dimension Learning Style N Percentage Processing Active 10 58.8% Reflective 7 41.2% Perception Sensing 13 76.5% Intuitive 4 23.5% Input Visual 14 82.4% Verbal 3 17.6% Understanding Sequential 10 58.8% Global 7 41.2% Table 4. Results of the acceptance questionnaire. Item No. Agree or Strongly Agree Neutral Disagree or Strongly Disagree 1 58.8% 17.6% 23.5% 2 70.6% 23.5% 5.9% 3 64.7% 23.5% 11.8% 4 70.6% 29.4% 0.0% 5 58.8% 29.4% 11.8% 6 41.2% 29.4% 29.4% 7 58.8% 41.2% 0.0% 8 52.9% 47.1% 0.0% 9 58.8% 41.2% 0.0% 10 64.7% 29.4% 5.9% 11 64.7% 29.4% 5.9% 12 47.1% 41.2% 11.8%  G. Cheng, T.-L. Wong 4.2. Students’ Acceptance of SL Results of students’ acceptance of SL are illustrated in Table 4. When asked about resources, a clear majority agreed that the resources in SL attract their attention (70.6%) and help them to understand course content (64.7%). With regard to communication, most participants agreed that it is advantageous to meet someone in SL compared to meeting them using instant messengers (70.6%) and webcam chat (58.8%). With respect to identity play, over half responded that SL can provide opportunity for them to engage in self-expression (58.8%) and help them overcome social anxiety and shyness (58.8%). Finally, as far as learning satisfaction is concerned, a majority (64.7%) felt comfortable to use SL and enjoyed the experience of using it. In considering the four aspects of SL, the results suggest that students generally accepted the use of SL as an educational tool in the ‘Digital Imaging’ course. However, two concerns should be noted. First, SL should not be used to replace face-to-face class interactions, as evidenced by the relatively low percentage of agreement with item 6. Second, SL may work as a good educational tool for some courses, but may not for some others. That is why most participants reported that they enjoy the experience of using SL in the “Digital Imaging” course, but less than half indicated that they are willing to continue using SL for learning in other courses. 4.3. Correlation Analysis Table 5 presents the Pearson correlation coefficients between dimensions of learning style and acceptance of SL. Results show that among the four dimensions of learning style, processing was significantly positively corre- lated with acceptance of identity play in SL (item 7: r = 0.598, p < 0.01; item 8: r = 0.521, p < 0.05; item 9: r = 0.598, p < 0.01) and willingness to use SL for learning in other courses (item 12: r = 0.439, p < 0.05), while un- derstanding was significantly positively correlated with acceptance of resources in SL (item 3: r = 0.418, p < 0.05). The results of correlation analysis suggest that active learners, who prefer to actively experiment with their learning through hands-on activities, are more likely to try out different avatars in order to express themselves, to explore different possible identities in the real world, and to overcome social anxiety and shyness. The feature of avatar creation in the virtual world is considered an important factor to support exploration of identities, and also a great opportunity to enhance learning motivation [16]. In SL, users are allowed to custo- mise and personalise the appearance and behavior of their avatars. They can also create, explore and interact with virtual objects in a 3D environment. Obviously, these functionalities offered by SL can satisfy the learning preference of active learners. Table 5. Results of correlation analysis. Item No. Processing Perception Input Understanding 1 0.053 −0.116 −0.059 −0.031 2 0.124 −0.285 −0.283 −0.180 3 −0.050 0.276 0.159 0.418* 4 0.175 0.232 0.092 0.275 5 0.341 0.305 0.021 0.359 6 0.119 −0.077 −0.264 0.106 7 0.598** −0.175 −0.380 0.105 8 0.521* −0.197 −0.392 0.070 9 0.598** −0.175 −0.380 0.105 10 0.256 0.186 −0.095 0.307 11 0.256 0.186 −0.095 0.307 12 0.439* 0.213 −0.053 0.295 **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (1-tailed), *Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (1-tailed).  G. Cheng, T.-L. Wong 4.4. Instructor Feedback This section discusses the qualitative results about the benefits and drawbacks of using SL for teaching and learning in higher education. Data was drawn from a semi-structured interview conducted with the course in- structor. The interview protocol comprised of three guiding questions: 1) could you describe your views on us- ing SL in your course? 2) could you name any aspects of SL you find most useful in your course? and 3) what were the major challenges of using SL in you course? After analysing interview transcripts, four key themes were identified: 1) motivation, 2) usefulness, 3) identity exploration, and 4) resources issues (e.g. time and equipment). They are described below. The course instructor noted that many students were very enthusiastic and motivated to participate in SL- based learning activities because SL could provide them with fresh knowledge and hands-on experience of the virtual world. Moreover, the instructor also found that students generally welcomed the novelty from traditional classroom activities and they were fascinated by the 3-D environment. The observation is consistent with the percentage of agreement with item 2 in Table 4. One of the course objectives was to increase students’ awareness on the physicality of printed materials in different environments. The course instructor pointed out that SL is useful because there is a direct link between this course objective and the SL-based learning activities. Students were provided with an opportunity to identi- fy the differences in printed materials between the physical and virtual worlds by viewing and interacting with real-world objects in SL. In this regard, SL can serve as an educational tool to facilitate students in developing the knowledge and skills that they were expected to acquire in the course. This view was shared by a majority of students, as derived from the percentage of agreement with item 3 in Table 4. Furthermore, the course instructor also expressed the view that a virtual object can be made at almost no cost when compared to its real counterpart in the physical world. Some students preferred to produce their artwork in digital format rather than a hard copy, partly because of economic factors, which gave rise to the use of SL in the course. Additionally, the course instructor found that most students enjoyed taking part in role-play activities by creating their own avatars to represent a professional artist. It was also observed that students were more confi- dent and less anxious to do the role-play activities and to express themselves in SL than in real classroom set- tings. The course instructor indicated that avatar creation is a valuable feature of SL that can encourage students to explore different possible identities through role play. Two issues that emerged from the interview data relate to the implementation challenges. First, the course in- structor raised a concern about the additional time required to provide students with assistance in using different functions offered by SL. Such concern points to the need to allocate more time for teaching and learning when SL is pedagogically applied to a learning context. Second, the course instructor reported that students’ occasio- nally encountered technical problems like motion lags, object blurs or even system crashes when using SL. The problem was mainly due to a lack of computing hardware and networking facilities meeting the system require- ments of SL in class. 5. Concluding Remarks To recapitulate, this study contributes to address the following two research questions: 1) what is the relation- ship between students’ learning styles and their acceptance of using SL for learning? and 2) from teacher’s perspective, what are the benefits and drawbacks of SL that may influence the acceptance of using SL for edu- cational use? First, the study used the Index of Learning Styles (ILS) to measure learning styles of a group of 17 undergra- duate students taking a Visual Arts course called “Digital Imaging”. Results of the ILS show that the most pre- ferred learning style was visual learning (82.4%), indicating that a clear majority of participants prefer to study materials using graphical and visual representation. Next, the study used a questionnaire to evaluate students’ acceptance of SL in terms of four aspects: 1) re- sources, 2) communication, 3) identity play, and 4) learning satisfaction. Results of the acceptance questionnaire suggest that over half of participants generally accepted the use of SL as an educational tool in the “Digital Im- aging” co u rse. A further step was also taken to explore the relationship between learning styles and acceptance of SL. Re- sults of correlation analysis mainly suggest that the processing dimension of learning style is significantly posi-  G. Cheng, T.-L. Wong tively correlated with the identity play aspect of SL. Specifically, active learners are more likely to try out dif- ferent avatars in order to express themselves, to explore different possible identities in the real world, and to overcome social anxiety and shyness. Besides, it was also found that active learners are more likely to continue using SL for learning in other courses. Finally, a semi-structured interview was conducted with the course instructor to collect further information about the benefits and drawbacks of using SL for teaching and learning in class. An analysis of interview tran- scripts validated the quantitative results. On the other hand, the analysis also called for the need to allocate addi- tional time and powerful computing equipment for effective implementation of SL. Notwithstanding the small sample size, this study will advance further work in designing effective practice and pedagogy with the use of SL. References [1] Bell, M.W. (2008) Toward a definition of “virtual worlds”. Journal of Virtual Worlds Research, 1, 1-5. https://journals.tdl.org/jvwr/article/view/283/237 [2] Fetscherin, M. and Lattemann, C. (2008) User acceptance of virtual worlds. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 9, 231-242. [3] Warburton, S. (2009) Second life in higher education: Assessing the potential for and the barriers to deploying virtual worlds in learning and teaching. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40, 414-426. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.00952.x [4] Halvorson, W., Ewing, M. and Windisch, L. (2011) Using second life to teach about marketing in second life. Journal of Marketing Education, 33, 217-228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0273475311410854 [5] Houser, R., Thoma, S., Coppock, A., Mazer, M. and Midkiff, L. (2011) Learning ethics through virtual fieldtrips: Teaching ethical theories through virtual experiences. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Edu- cation, 23, 260-268. [6] Jamaludin, A., Chee, Y.S. and Ho, C.M.L. (2009) Fostering argumentative knowledge construction through enactive role play in second life. Computers & Education, 53, 317-329. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.02.009 [7] Rogers, L. (2011) Developing simulations in multi-user environments to enhance healthcare education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42, 608-615. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01057.x [8] Wang, Y. and Braman, J. (2009) Extending the classroom through second life. J ournal of Information Systems Educa- tion, 20, 235-247. [9] Vogel, D., Guo, M., Zhou, P., Tian, S. and Zhang, J. (2008) In search of second life nirvana. Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology, 5, 11-28. [10] Wang, C., Song, H., Xia, F. and Yan, Q. (2009) Integrating second life into an EFL program: Students’ perspectives. Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange, 2, 1-16. [11] Manochehr, N.-N. (2006) The influence of learning styles on learners in e-learning environments: An empirical study. Computers in Higher Education Economics Review, 18, 10-14. [12] Felder, R.M. and Spurlin, J.E. (2005) A validation study of the index of learning styles. Applications, reliability, and validity of the index of learning styles. International Journal of Engineering Education, 21, 103-112. [13] Felder, R.M. and Soloman, B.A. (1994) Index of learning styles. http://www4.ncsu.edu/unity/lockers/users/f/felder/public/ILSdir/ILS.pdf [14] Wang, Y.S. (2003) Assessment of learner satisfaction with asynchronous electronic learning systems. Information and Management, 41, 75-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7206(03)00028-4 [15] Willems, J. (2011) Using learning styles data to inform e-learning design: A study comparing undergraduates, post- graduates and e-educators. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27, 863-880. [16] Lee, J.J. and Hoadley, C.M. (2007) Leveraging identity to make learning fun: Possible selves and experiential learning in massively multiplayer online games (MMOGs). Innovate: Journal of Online Education, 3. http://www.innovateonline.info/index.php?view=article&id=348

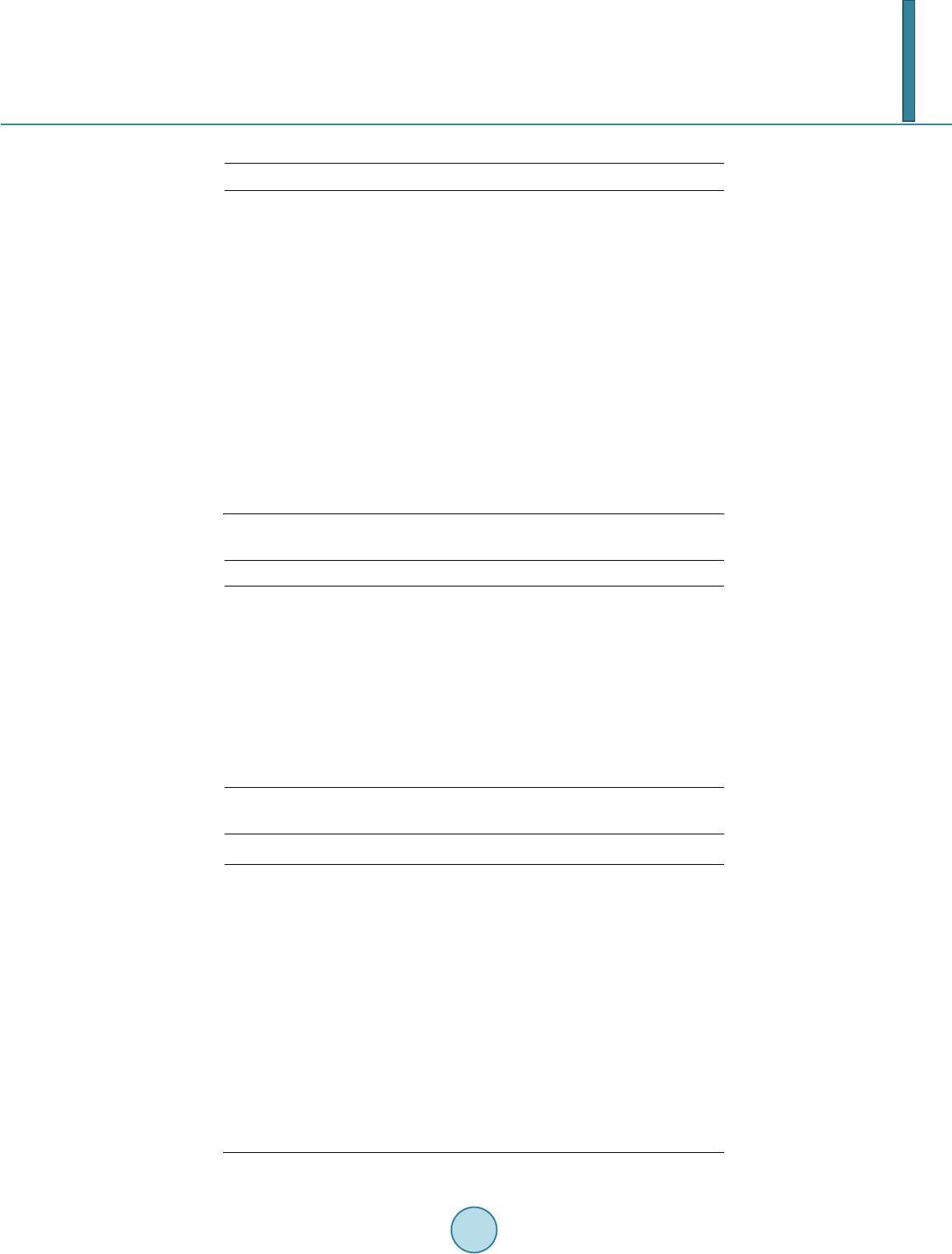

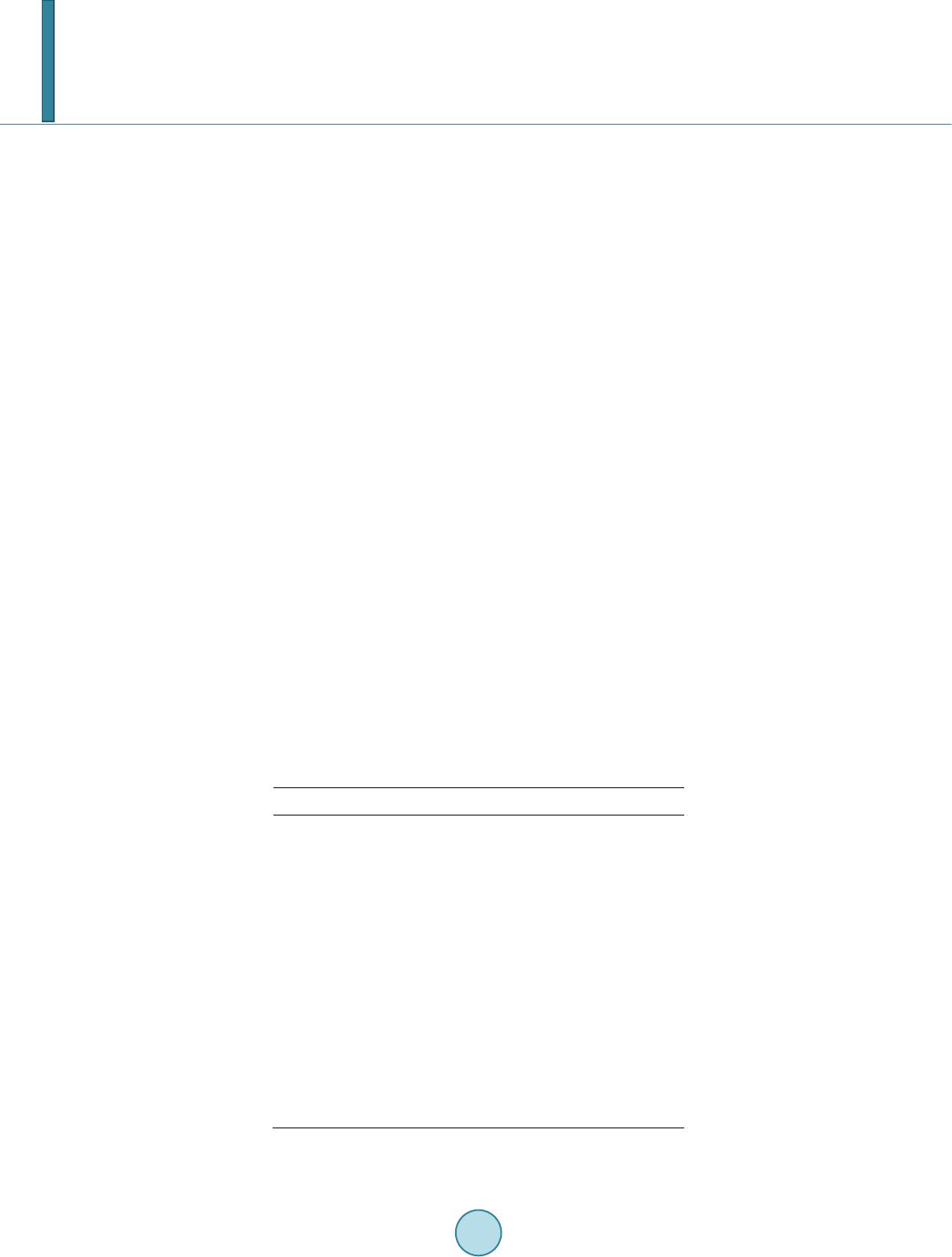

|