S. M. U. P. MAWALAGEDERA ET AL.

OPEN ACCESS

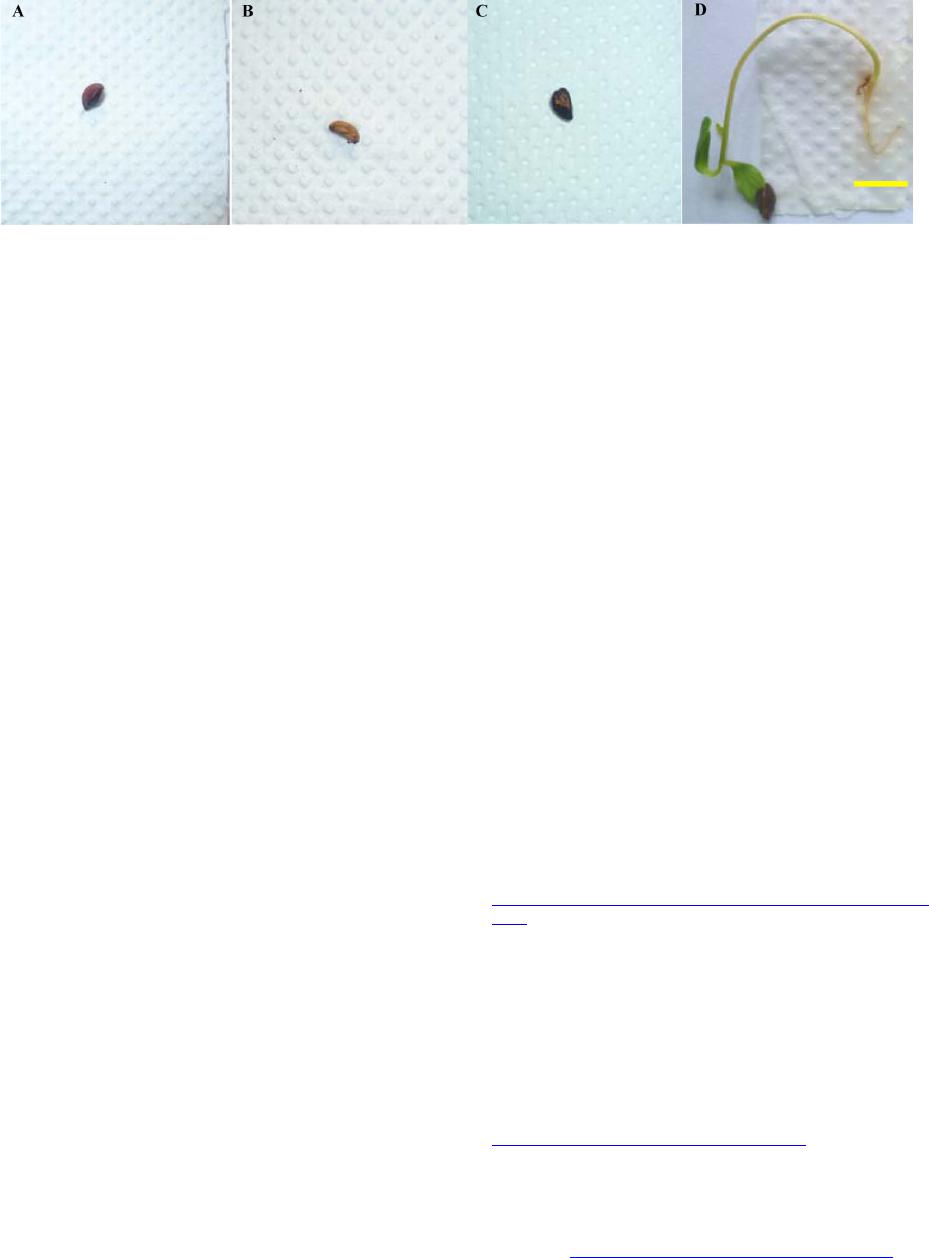

Figure 2.

Germination among pre sowin g treatments of P. emblic a seeds; (A) Ungerminated seed none treated; (B) Ungerminated seed pre treated wit h

1% gibberellin and removal of seed coat; (C) Ungerminated seed pre treated with seed scarification and (D) Seedling developed from seed pre

treated with 1% gibberellin and seed scarification. Scale bar represent 1 cm. The photos were taken after 92 days of the pre treatment and

placement on the moist paper towels for germination.

a successful micro propagation protocol for P. emblica in order

to expand its commercial market.

According to the observations made P. emblica seeds seem

to have seed coat imposed dormancy as in peach (Mehanna &

Martin, 1985). Research conducted with Arabidopsis gibberel-

lin deficient mutant strains indicated that, seed coat imposed

dormancy can be overridden by application of gibberellin at the

stage of germination (Foley, 2001). It has been found that

gibbrrelin can induce the expressions and repression RGL2

(gibbrrelin-response height-regulating factors) which acts as an

integrator of environmental and endogenous cues for germina-

tion (Peng & Harberd, 2002). Therefore by manipulating the

concentration of gibberellin during seed pre treatment it would

be possible to change the germination percentage and reduce

the time taken for germination. In species such as Penstemon

digitalis the germination percentage and rate increases up to a

threshold concentration of gibberellins (Mello et al., 2009).

However it is inconclusive to comment that gibberellin concen-

tration has a directly proportionate variation with germination

percentage in P. emblica.

The seeds of P. emblica are enclosed within a hardened en-

docarp of approximately 1 cm in diameter (Dassanayake and

Fosberg, 1986). To break the seed coat imposed physical dor-

mancy scarification of seed coat was used. It has resulted in

increasing the germination potential of many species as African

Locust Bean (Aliero, 2004) and Pedicularis (Li et al., 2007). In

Indian dry forests P. emblica seeds are dispersed by ruminants

(Prasad et al., 2004). But seeds regurgitated by ruminants have

a lower germination potential (22%) than seeds which are un-

consumed (72%; Prasad et al., 2004). Other than ruminants no

other species have shown frugivore in relation to P. emblica

(Prasad et al., 2004). This could be due to the high astringency

of the drupe. Therefore it is possible that the seeds of P. embli-

ca undergo passive dispersal. Passive dispersal requires long

term viabi lity of the seed unti l the seed come in to c ontact with

a suitable substratum. It is possible that this seed coat imposed

dormancy of P. emblica is a safety measure to maintain the

viability of seeds until landing on to an appropriate microenvi-

ronment. Thus the seeds of P. emblica are classified as semi

orthodox (Pushpakumara et al., 2007).

In summary these observations and results shows that P. em-

blica has a high seed coat imposed dormancy which can be

overridden by gibberellin pre treatment. Yet further studies are

needed to assess the effect of plant growth regulators control-

ling the P. emblica seed dormancy in order to provide quality

planting material for growers which will help to promote P.

emblica from its underutilized fruit crop status.

Conclusion

The seed dormancy of P. emblica can be overridden by the

pre treatment where the seed coat was scarified and treated with

1% gibberellin. This method can be used to germinate seeds of

P. emblica in breeding programs and in any other studies which

require seedlings.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by University of Peradeniya, Sri

Lanka Research Grant (RG/2013/15/S).

REFERENCES

Aliero, B. L. (2004). Effects of sulphuric acid, mechanical scarification

and wet heat treatments on germination of seeds of African locust

bean tree. Parkia biglobosa. African Journal of Biotechnology, 3,

179-181.

Dassanayake, M. D., & Fosberg, F. R. (1988). A revised hand book of

the Flora of Ceylon (pp. 219-220). New Delhi: Model Press Pvt. Ltd.

Foley, M. E. (2001). Seed dormancy: An update on terminology, phy-

siological genetics, and q uantitative trait loci regulating ger minabili-

ty. Weed Science, 49, 305-317.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1614/0043-1745(2001)049[0305:SDAUOT]2.0.

CO;2

Goyal, D., & Bhadauria, S. (2008). In vitro shoot proliferation in Em-

blica officinalis var. Balwant fro m nodal explants . Indian Journal of

Biotechnology, 7, 394-397.

Krishnaveni, M., & Mirunalini, S. (2010). Therapeutic potential of

Phyllanthus emblica (amla): The ayurvedic wo nder. Journal of Basic

and Clinical Phy isiology and Pharmacology, 21, 93-105.

Li, A. R., Guan, K. Y., & Probert, R. J. (2007). Ef fects of light, scarifi-

cation, and gibberellic acid on seed germination of eigh t Pedicularis

species from Yunnan, China. Hort Science, 42, 1259-1262.

Mehanna, H. T., & Martin, G. C. (1985). Effect of seed coat on peach

seed germination. Scientia Horticulturae, 25, 247-254.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-4238(85)90122-0

Mello, M. A., Streck, N. A., Blankenship, E. E., & Paparozzi, E. T.

(2009). Gibberellic acid promotes seed germination in Penstemon

digitalis cv. Husker Red. HortSceince, 44, 870-873.

Peng, J., & Ha rberd, N. P. (2002). The role of GA-mediated signalling

in the control of se ed g ermination . C urrent Opinion in Plant Biology,

5, 376-381. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00279-0

Prasad, S., Chellam, R., Krishnaswamy, J., & Goyal, S. P. (2004).

Frugivory of Phyllanthus emblica at Rajaji Natinal Park, northwest