Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

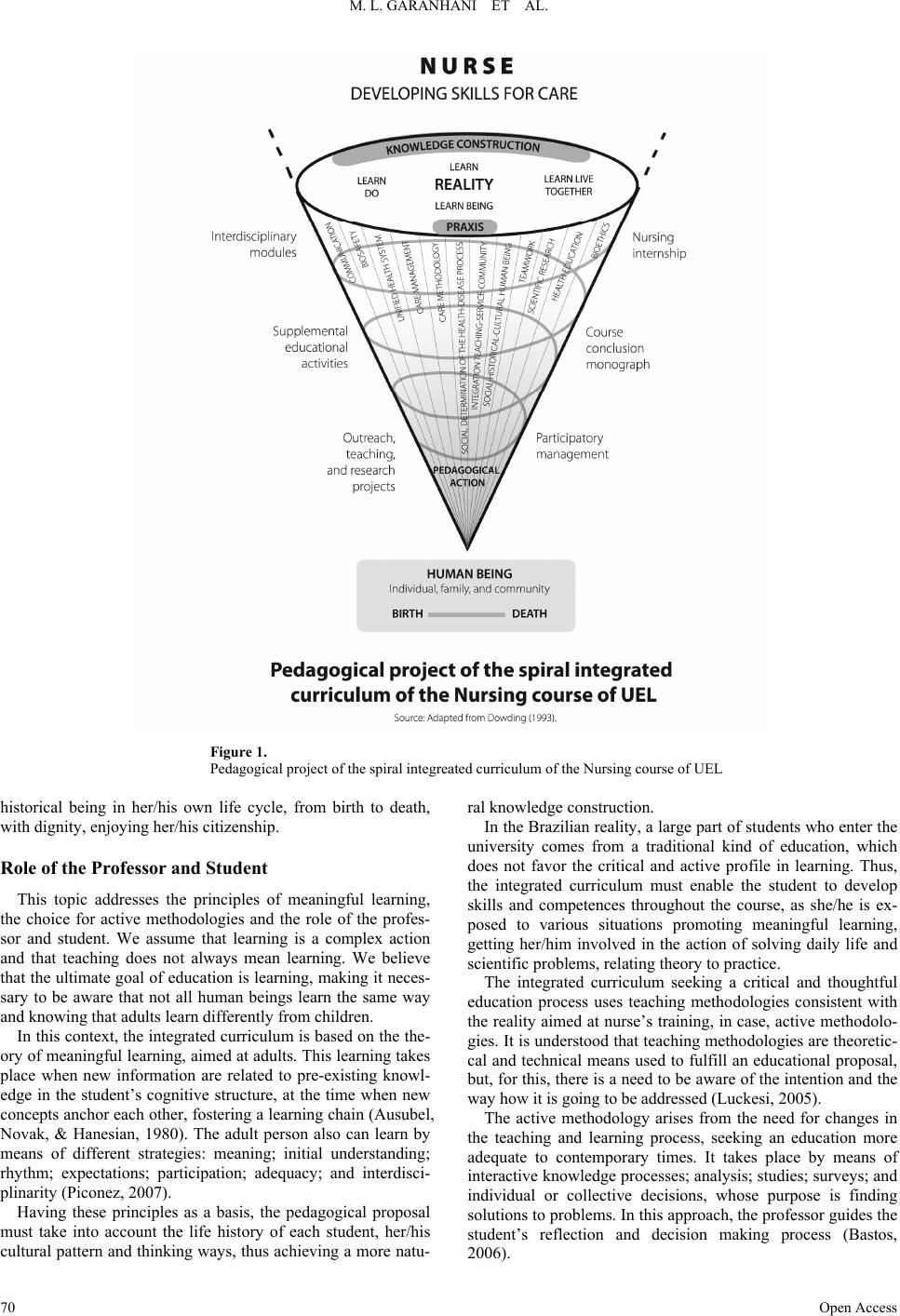

Creative Education 2013. Vol.4, No.12B, 66-74 Published Online December 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2013.412A2010 Open Access 66 Integrated Nursing Curriculum in Brazil: A 13-Year Experience Mara Lúcia Garanhani1, Marli Terezinha Oliveira Vannuchi1, Anaísa Cristina Pinto2*, Thayane Roberto Simões2, Maria Helena Dantas de Menezes Guariente1 1Department of Nursing of the State University of Londrina, Paraná, Brazil 2The State University of Londrina, Paraná, Brazil Email: *anaisacristina@gmail.com Received October 28th, 2013; revised November 28th, 2013; accepted December 5th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Mara Lúcia Garanhani et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2013 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Mara Lúcia Garanhani et al. All Copyright © 2013 are g ua rded by law and by SCIRP as a gua rdian. This article aims to describe the guiding principles and the operationalization of the integrated curriculum of the undergraduate course in Nursing of a public university in southern Brazil. This is an experience re- port by 3 curriculum managing professors and 2 graduate students in Nursing, who experience the peda- gogical proposal. The analysis comprised official documents and 2 books on this integrated Nursing cur- riculum, which has been developed for 13 years; it is presented in 4 topics: guiding principles; curricular structure; role of the professor and student; and collegiate management. We present reflections on the curriculum, expressing the framework supporting the proposal and the developmental strategies adopted. This experience points out the dialogical movement of participants in this education action, i.e. professors and students, from a critical and innovative perspective of nurse’s training. We conclude that the pathway reported highlights key themes of the pedagogical proposal, such as inseparability of theory and practice; the diversification of teaching strategies; the successive close approaches between contents in interdisci- plinary modules; learning evaluation from a two-dimensional perspective; early introduction of the stu- dent to different settings of professional practice; and the democratic and participatory management proc- ess in a collective construction. We hope to contribute to other institutions trying to develop an innovative methodology for nurse’s training. Keywords: Nursing Education; Curriculum; Teaching-Learning Process Introduction Changes in the political, economic, and social scenarios of education and health care in Brazil and in the world have re- quired transformations in nurse’s profile. There is a need for integration between the health care field and education, in order to rethink nurse’s training, aimed at developing a citizen who is more critical, flexible, versatile, thoughtful, and capable of facing challenges of modernity with regard to health promotion (Martinelli et al., 2011). Thus, teaching in universities has favored curricula which involve more active learning processes, encouraging exchange of information between professors, students, health care profes- sionals, and users of health care services, in order to develop student’s ability to properly act when faced by situations posed by professional practice, stimulating creativity (de Almeida, 2003). The construction of the integrated curriculum of the under- graduate course in Nursing of the State University of Londrina (UEL), Paraná, Brazil, implemented in 2000, involves the commitment of professors to pursue a professional training which considers the comprehensiveness of care for the individ- ual, family, and community; the determining factors of the health-illness process; the social and economic factors related to the syllabus; continued multiprofessional and interdiscipli- nary activities, instead of occasional ones; integration between the services and the community; and, also, the idea that the student is a citizen who construes her/his knowledge and is in charge of developing her/his technical, political, and ethical competences in an active, critical, and thoughtful way. The process for constructing the integrated curriculum was permeated with many doubts, but, also, some convictions. One of them, theoretically supported by Sacristán (1998), is the premise that a curriculum is something constructed by means of an intense participatory action, in an open deliberation process involving the participating actors, with no imposed decisions. Even when these actors used their own resources, values, and beliefs in debates and discussions, the aim was establishing partnership and consensus. Another conviction was that the more legitimate and negoti- ated the agreement between actors involved in the daily prac- tice, the greater the possibility of joining forces to make it come true and turn this practice into the curricular organization. Throughout the curriculum construction process, we wished for change and were afraid of an uncertain future. However, the *Corresponding author.  M. L. GARANHANI ET AL. group went on, defining its pathway, daring to think and start a new stage in its pedagogical practice, always guided by the Nursing Collegiate, the legitimate body representing the whole course, responsible for driving the process of curriculum trans- formation, observing the collective construction process. In this context, the Pedagogical Political Project of the inte- grated curriculum of the nursing course of UEL was con- structed and approved, on December 10, 1999, and its deploy- ment was scheduled to take place in the first half of 2000—at the dawn of the XXI century. New century, new curriculum! Thirteen years after the deployment of this curriculum, revis- iting its history allows us to report the routes taken and contrib- ute to other education institutions which are undergoing a cur- riculum change process. It also enables us to have a collective reflection by actors involved in this construction, providing other people with the possibility of taking a critical look at the need for facing together the challenge of achieving the quality required in nurse’s education. Thus, this article aims to describe the guiding principles and the operationalization of an integrated curriculum of an under- graduate course in Nursing of a public university in southern Brazil. Methodological Pathway This is an experience report of the process experienced in the Nursing course of UEL since the construction of the integrated curriculum. Londrina is a town with around 500,000 inhabitants, in the state of Paraná, southern Brazil. UEL is located at this town; it has 53 courses, among them the undergraduate course in Nurs- ing, created in 1971, and its first group of students joined in 1972. Most professors of the Nursing course are allocated in the Departments of Nursing and the Department of Collective Health of the Center for Health Sciences of UEL, and there are other professors working in departments of the centers for Bio- logical Sciences and Humanities. The faculty is characterized as a group constantly involved in discussions, struggles, and proposals for curricular changes in nurse’s training, committed to improving the quality of teaching and the provision of health services to the population. In the quest for quality of teaching and professional training, the course underwent seven curricular reforms until 2012; among them, stand out the creation of the nursing internship, in the curriculum for 1992, and the deployment of the integrated curriculum since 2000. In 2012, the Nursing course of UEL celebrated 40 years of activities and 13 years since the imple- mentation of the integrated curriculum. It enrolls 60 students per year, who undergo the so-called “vestibular”, lasting four years in full-time, totaling 4152 hours of free education to the student. The preparation of this report was based on the perception of 3 curriculum managing professors and 2 graduate students in Nursing, who experienced the pedagogical proposal. We also used some official documents and 2 books produced within this 13-year period (Dellaroza & Vannuchi, 2005; Kikuchi; Guari- ente, 2012). Access to the documents was sought after approval and authorization by the course collegiate. The authors agreed to use the confidential information accessed only for scientific purposes, ensuring confidentiality and secrecy. This report is part of the research project “Integrated curriculum of a Nursing course: pedagogical management and professional training”, approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the institution, under the Protocol 0323.0.268.000-11. Development The development of the integrated curriculum is presented in 4 topics: guiding principles; curricular structure; role of the professor and student; and collegiate management. Reflections on the theme are expressed, allowing us to think through the perspective of those who teach and those who learn in a prob- lem-solving and meaningful way, aimed at professional training in Nursing and Health Care. Guiding Principles of the Integrated Curriculum The pedagogical principles guiding the integrated Nursing curriculum are based on the paradigmatic crisis of science and education, where the discussion on the agenda involves the need to go beyond a practice which reaffirms the fragmentation of knowledge, breaking down the boundaries between special- ties of each discipline, in search of a comprehensive integra- tion. In this context, in the pedagogical proposal of the integrated curriculum, the human being is defined as being able to trans- form the conditions of her/his existence by means of her/his worldview, which permeates her/his social relations. These, in turn, determine the organizational structure and the production in society. The insertion of the human being in the productive process may determine the health-illness process. In this proposal, nursing is understood as a socially, politi- cally, and historically determined practice, which aims to care for the human being in all life cycles, contributing to health promotion, prevention, recovery, and rehabilitation. So, the nurse’s profile aimed by this curriculum consists in an ethical and humanistic professional, politically responsible and able to perform an intentional work, becoming a social transformation agent. In the integrated Nursing curriculum, education is understood as a social practice and it must contribute to the development of the human being as a whole, enabling transformative actions in the construction of citizenship and society. The integrated curriculum is defined as that which organizes knowledge, integrating the contents that keep a relation to each other. For this, there is a subordination of the kinds of knowl- edge previously isolated to a central idea. There are four prince- ples guiding an integrated curriculum: comprehensiveness, interdisciplinarity, relationship between theory and practice, and curriculum as a process (Romano, 2000). The principle of comprehensiveness means that the whole and the parts are analyzed at a single moment and together, interconnecting concepts and inter-relating contents which come from various knowledge areas, addressed in the curricular disciplines. Edgar Morin, an educator of contemporary times, reinforces this principle of comprehensiveness by claiming that the whole is included into the parts, and the parts are included into the whole (Morin, 2001). Thus, in the integrated curricu- lum this principle means that the whole is simultaneously con- structed by the parts, assuming the principles of interdiscipli- narity and the relationship between theory and practice. The principle of interdisciplinary approaches the inter-rela- tionship and dialogue between the various disciplines, preserve- Open Access 67  M. L. GARANHANI ET AL. Open Access 68 ing autonomy and depth of specific kinds of knowledge, aiming at a multidimensional understanding of phenomena. Brazilian theorists advocate for the interdisciplinary integration aimed at the problems of health care, considering that the contents of disciplines which help understanding this reality interact in dynamic way, establishing connections and mediations between themselves (Merhy, 2002; Morin, 2007; Romano, 2000). The principle of relationship between theory and practice claims that these poles must be simultaneously worked on, constituting an indissoluble unity, where the practice is not simply the application of theory and the theory is not designed without practice. The fourth principle highlights the curriculum as a process. This must remain open to discussion, criticism, and transforma- tion, since it is continuously constructed and reconstructed with a succession of changes. Edgar Morin (2010) argues that the reductionism that traditional knowledge has undergone led us to lose the notions of multiplicity and diversity. So, it is cautious and useful to have openness and flexibility in the curricular structures designed. There is a need to be receptive to emergen- cies, bifurcations, and changes taking place in learning envi- ronments, because non-linearity and indeterminism may require a route change, causing an initially unplanned and insignificant action to turn into something important and meaningful at an- other moment of the process (Moraes, 2010). In addition to the 4 principles mentioned above, the profes- sors of the course have elected a fifth one: integration between teaching, service, and community. This choice was based on the appreciation of space shared by professors, students, health care professionals, and users. Article 14 of the Brazilian Health Organic Law provides for the creation of Permanent Commis- sions for integration between health care services and High School and Higher Education institutions. Article 27 of this Law states that the public services included into the Unified Health System (SUS) constitute practice fields for teaching and research, by means of specific standards, designed along with the education system (Lei no 8080, 1990). Curricular Structure When preparing the pedagogical proposal of the integrated curriculum, there was a structural break with the current model, which was focused on traditional disciplines. The aim was making the academic knowledge interdisciplinary, by means of actual teamwork experiences, in a relationship involving recip- rocity and shared property, allowing the dialogue between the various disciplines in the pursuit of integration. It was intended to overcome failures derived from a too compartmentalized science which has no communication (Santomé, 1998). With this purpose, the disciplines were replaced by the interdiscipli- nary modules. Interdisciplinary modules are didactic/pedagogical organiza- tions structured in all learning grades of the course. They are characterized as interdisciplinary activities which seek to de- velop competences through the inter-relation of concepts and organization of activities, encouraging meaningful learning by using active methodological strategies. Each module must en- sure the improvement of cognitive (knowledge), psychomotor (know-how), and attitudinal (know how to be and know how to live along) skills, needed to achieve the skills and competences that make up the nurse’s profile intended. They are organized into teaching units that guide and lead the student to gradually acquire a greater breadth and depth with regard to her/his knowledge improvement and construction. The teaching plans used in the modules of the Nursing course were named planning and development notebooks for the inter- disciplinary modules. These notebooks are structured this way: general purpose; number of hours; professors and departments in charge; knowledge areas involved; thematic tree and/or con- ceptual map; competences; specific skills and abilities; teaching units and activity sequences; assessment criteria; schedule; references; and appendices. For integrating the basic and clinical cycle, the concepts of basic sciences were incorporated throughout the modules, try- ing to relate them to their application to professional practice. Thus, professors from the basic sciences and professional de- partments involved in nurse’s training started working together, something which led to the reorganization and restructuring of the work process in the course. Currently, the curricular matrix has 18 modules and it is set as shown in Table 1. The operationalization of interdisciplinary modules takes place according to the activities which are going to be devel- oped. Thus, students are gathered in small groups (from 15 to 20 people), large groups (30 people), and plenary meetings (60 people), all of them mediated by a professor. The activities of classes and internships, at different scenarios of nurse’s work, are also organized into modules from the first grade of the course. Early insertion of the student in the service practice favors the understanding of the relationship between theory and practice. Table 1. Curricular matrix of a nur s ing c ourse in southern Br azi l. University an d t he Nursing Course at UEL Health-Illnes s P rocess Vacation Morphophysiologic al and Psych ic Aspects of the Human Being 1st grade Interdisciplinary Practices and the Interaction between Teaching, Service, and Community I Caring Practices Vacation Organizat io n of Health Services and Nursing Adult Health IMaterial and Biosafety C enter 2nd grade Interdisciplinary Practices and the Interaction between Teaching, Service, and Community II Adult Health II Vacation Children and Adol escents’ Health Women’s He alth and Gender 3rd grade Course Conclusion Mon ograph I Communicable Diseases Mental Health Critical Pa t ient Care Supervised In ternship (Nursing Internship) Supervised In ternship (Nursing Internship) 4th grade Course Conclusion Mon ograph II  M. L. GARANHANI ET AL. Thus, the academic activities undertaken by students com- prise theoretical groups; laboratory practices; practices at dif- ferent health care services, schools, nursery schools, and along with the community; interdisciplinary and multiprofessional practices; course conclusion monograph; and supervised in- ternship, named nursing internship. Supplementary academic activities are also proposals, including outreach, teaching, and research projects, participation in scientific events, tutorships, extracurricular internships, among others. The pedagogical project also allows us to approach cross- sectional themes. They are teaching guidelines which aim to contribute to the individual’s overall training, in order to enable her/his qualified participation in society. Cross-sectionality promotes a comprehensive understanding of knowledge objects and perception of the subject as an agent in the production of her/his knowledge, overcoming the dichotomy between them (Ministério da Educação, 1998). In the integrated curriculum, the term cross-sectional themes was replaced by the designation saps, keeping the same mean- ing, i.e. what goes through curricular disciplines. The saps must be included in the interdisciplinary modules, with a greater or lesser close approach degree, so that students incorporate them throughout the grades until graduating from the course. The saps are driving forces of academic activities, increas- ingly connected to the specific contents and crucial skills from the va r ious modules. 1) Social-historical-cultural human being: the human being is understood as a whole, with biological, psychological, spiritual, and social interconnected and interdependent characteristics. She/he is determined by her/his personal life history, being included into a social group. Her/his insertion in the productive process determines her/his health-illness process. 2) Social determination of the health-illness process: com- prises the comprehensive view of the human being in the social and historical determination of her/his sickening process. 3) Unified Health System: it is the current health care system in Brazil since 1988, with the promulgation of the Federal Con- stitution and the federal Law 8080/90. Its constitutional prince- ples are universality; and equality and comprehensiveness. Its guidelines are decentralization; regionalization; hierarchy; solvability; and popular participation. These principles and guidelines drive the public policies aimed at health care. 4) Care management: it is an administrative tool that the nurse must use to coordinate and systematize the provision of care. It must be planned, analyzed, and assessed, considering its inter-relation nature (Christovam & Santos, 2004). 5) Care methodology: operationalized by means of the nurs- ing process, aiming to systematize care through the following steps: history; diagnosis; care plan; prescription; and nursing evolution. These steps constitute the nursing care systematize- tion, a nurse’s exclusive work tool established by the Profes- sional Practice Law (Lei no 7,498/86), which provides nursing care with autonomy and independence. 6) Integration teaching-service-community: connection of the undergraduate and graduate centers to the health care services and the community. It allows searching for solutions to health problems, enabling the transformation of teaching and profess- sional practices. It aims to make the student aware of the need to improve intra and interpersonal relationships, acknowledging popular kinds of knowledge. 7) Health education: it regards education and health as con- cepts connected to the historicity of human beings, their culture, social scenario, and worldview, leading to changes in health care actions. A role played by the nurse is that of educator. Stefanini (2004) cites that health education is understood as a transformation process which promotes the individuals’ critical awareness with regard to their own health problems, encourage- ing them to seek collective solutions. 8) Communication: it comprises the verbal, non-verbal, and written communication process in health care, crucial for nurse’s work. A communication process, at any level, may facilitate or pose barriers to the establishment of a therapeutic and interpersonal relationship between work teams. 9) Scientific research: research helps the students to improve scientific reasoning, critical thought, and actions aimed at im- proving nursing care and the population’s quality of life. 10) Teamwork: in Brazil, nursing is a profession practiced by a multidisciplinary team, involving professionals trained at a High School or Higher Education level. Teamwork is a vital requirement to obtain satisfactory results in the provision of health care. 11) Bioethics: it addresses theoretical contents related to pro- fessional ethics; citizenship; human rights; patient’s rights; social inequality; human vulnerability; allocation of health care resources; social justice; autonomy; informed consent; human dignity; assisted fertilization; euthanasia; dysthanasia, palliative care; research involving human beings; organ donation; among others. 12) Biosafety: nursing is a profession included in a society which exposes it to unhealthy settings and risks arising from the work process. Biosafety gathers measures aimed at avoiding physical, ergonomic, chemical, biological, psychological, and safety risks. It involves thinking through and deploying actions which favor health promotion, maintenance, and protection, as well as human life. In order to combine the principles adopted in the integrated curriculum, it was decided to structure it as a spiral-like cur- riculum, which proposes a course organization coming from the general towards the specific knowledge, at increasing levels of complexity and involving successive close approaches (Dowd- ing, 1993). This curriculum organization way supports the con- struction of knowledge sequences defined according to knowl- edge the competences intended for the profile of prospective nurses. Thus, new kinds of knowledge and skills (cognitive, affective, and psychomotor) are introduced at subsequent mo- ments, resuming what is already known and sustaining the in- terconnections to previously acquired information (Dessunti, 2012). Figure 1 displays the integrated Nursing curriculum as a cone, illustrating the spiral-like movement. This movement explains the intention of gradually exposing cross-sectional themes, which must be addressed from the 1st to the 4th grades, comprising increasingly complex levels and successive close approaches. Externally, there are activities highlighted in the figure which, together, enable us to consoli- date the development of knowledge, skills, and competences intended to be included in nurse’s profile. Within the cone we observe the kinds of knowledge, skills, and attitudes distributed into the four domains proposed by Delors et al. (1999), learning, learning to do, learning to be, and learning to live together, realizing that these 4 learning ways constitute only one, i.e. there are many points of contact, relationship, and exchange. At the bottom of the figure, the human being is highlighted, the nursing care actions are aimed at her/him, who is regarde d as a Open Access 69  M. L. GARANHANI ET AL. Figure 1. Pedagogical project of the spiral integreated curriculum of the Nursing course of UEL historical being in her/his own life cycle, from birth to death, with dignity, enjoying her/his citizenship. Role of the Professor and Student This topic addresses the principles of meaningful learning, the choice for active methodologies and the role of the profes- sor and student. We assume that learning is a complex action and that teaching does not always mean learning. We believe that the ultimate goal of education is learning, making it neces- sary to be aware that not all human beings learn the same way and knowing that adults learn differently from children. In this context, the integrated curriculum is based on the the- ory of meaningful learning, aimed at adults. This learning takes place when new information are related to pre-existing knowl- edge in the student’s cognitive structure, at the time when new concepts anchor each other, fostering a learning chain (Ausubel, Novak, & Hanesian, 1980). The adult person also can learn by means of different strategies: meaning; initial understanding; rhythm; expectations; participation; adequacy; and interdisci- plinarity (Piconez, 2007). Having these principles as a basis, the pedagogical proposal must take into account the life history of each student, her/his cultural pattern and thinking ways, thus achieving a more natu- ral knowledge construction. In the Brazilian reality, a large part of students who enter the university comes from a traditional kind of education, which does not favor the critical and active profile in learning. Thus, the integrated curriculum must enable the student to develop skills and competences throughout the course, as she/he is ex- posed to various situations promoting meaningful learning, getting her/him involved in the action of solving daily life and scientific problems, relating theory to practice. The integrated curriculum seeking a critical and thoughtful education process uses teaching methodologies consistent with the reality aimed at nurse’s training, in case, active methodolo- gies. It is understood that teaching methodologies are theoretic- cal and technical means used to fulfill an educational proposal, but, for this, there is a need to be aware of the intention and the way how it is going to be addressed (Luckesi, 2005). The active methodology arises from the need for changes in the teaching and learning process, seeking an education more adequate to contemporary times. It takes place by means of interactive knowledge processes; analysis; studies; surveys; and individual or collective decisions, whose purpose is finding solutions to problems. In this approach, the professor guides the student’s reflection and decision making process (Bastos, 2006). Open Access 70  M. L. GARANHANI ET AL. The active methodology breaks with the traditional model and it proposes to promote a student-driven teaching, turning the student into an active and participatory agent with regard to her/his learning process, leading her/him to learn how to learn. This process takes place in a dynamic way, using the student’s prior knowledge and connecting it to the newly acquired con- tents, establishing the construction of new kinds of knowledge and techniques. A study carried out by Tacla (2002) used problematization, an active methodology similar to Problem Based Learning (PBL), with undergraduate students in Nursing. It was found out that this methodology led participants to increase their con- fidence and discover abilities poorly explored by traditional teaching methods. For the author, it is not enough to teach con- tents, there is also a need to trigger attitudes that lead students to investigate, discuss, respect divergent positions, organize themselves, and make collective decisions. Active methodologies led to changes in professors’ role, mainly because many of them were trained through traditional methodologies. Thus, the professor takes the role of tutor, i.e. learning facilitator and mediator, and she/he must work in a conscious and continued way, seeking to awaken in the student her/his potential to intervene in reality. There is a need to be available to monitor this student, who is in an environment where unforeseen and unknown situations emerge. Professor’s role is triggering a cognitive conflict involving the student and promoting an action which requires search for information in order to understand and explain the theme under study. For this, it is possible to use questions, movies, plays, interviews, visits, dialogued lectures, case studies, experience reports, debates with guests from the external community, problem situations, spoken newspaper, portfolio, among others. Thus, it is a must that the professor leads the student to feel challenged and that she/he thinks of the problem as an obstacle that she/he is able to overcome (Garanhani, Takahashi, & Ki- kuchi, 2000; Garanhani, Alves, de Almeida, & de Araújo, 2012). In short, it is expected that professors: have technical com- petence regarding the contents to be worked on; use the prob- lem as a bridge to learning and improving the professional competence to solve daily life and scientific problems; create conditions so that the student asks about her/his knowledge and experience or about her/his intuitive ideas; mediating attitude in the teaching and learning process and appreciation of students’ prior knowledge, regarding them as a point of entry into their cognitive system and as a bridge to the incorporation of new information and t h e newly learn ed contents. The student is expected to: be critical, creative, and active, playing a leading role as someone aware of the process of changes; identify and relate her/his prior knowledge to the whole knowledge construction process; construct her/his know- ledge about a problem extracted from reality, through direct and/or indirect observation with a critical look, using such in- formation and scientific knowledge already constructed to de- sign and share an explanation which, even existing, starts being her/his own explanation for the phenomenon; understand not only the answer to the problems under study, but also be able to explain the process by means of which the solution was achieved; apply the knowledge constructed to various teaching and learning situations experienced. Within this teaching and learning context, there is a need to have an assessment able to cover all particularities of the train- ing process. Assessment from a critical pedagogical perspective may be thought through as a mediating space between teaching and learning, where student and professor seek an open and overt dialogue, allowing to set ways to overcome the difficul- ties found throughout the teaching and learning process (Álva- rez Méndez, 2002). It must have an ongoing nature, i.e. it must be continuous, democratic, procedural, diversified, comprehen- sive, systematic, intentional, inclusive, participatory, and sym- pathetic, contributing to the progress, development, or im- provement of the learning concerned (Silva, 2004; Brasil, 2003), and its function is collecting information, systematize, interpret, and intervene in order to promote meaningful learning. In 2005, as a result of maturation and collective construction by the group of professors and students, the course adopted an assessment system with a two-dimensional concept, involving the formative assessment, seeking to appreciate qualitative aspects to the detriment of quantitative ones, taking subjectivity as inherent to any assessment process. Demo (1999) claims that, in order to assess, we need a con- trastive scale, which may be quantitative (grade) or qualitative (concept), however, strictly speaking, there is no difference between grade and concept, since both of them refer to a scale. So, what has led the course to abolish the grade and adopt the concept (two-dimensional instead of multidimensional) was the strengthening of formative assessment. That is, it was clear for many professors that, either grade, concept, or any other term, what really matters is the professor’s commitment to learning and her/his decisions with regard to the assessment results, understanding that, at that time, working with a two-dimen- sional concept may strengthen the formative nature of assess- ment by means of the emphasis on feedback. Furthermore, this system does not operate using an average, i.e. an essential competence cannot be compensated by another one, something which allows the professor to clearly identify satisfactory and unsatisfactory performance. The assessment by means of a two-dimensional concept in the integrated curriculum requires the construction of crucial competences and skills, without which the student cannot move forward in the course, and it avoids classifying students as bet- ter or worse ones, something which constitutes a major conflict, both for students and professors. For conducting an assessment from this perspective, what is written within the classroom would not be enough; there is need for a qualitative approach taking into account complex everyday work situations, and that is the reason why the Nurs- ing course adopted an assessment based on performance, in order to achieve the competences defined for the nurse’s pro- file. Competences consist in the individual’s ability to connect and resort to her/his knowledge, skills, and values, with auto- nomy and critical attitude, in order to deal with her/his profes- sional tasks (Ramos, 2001). For this, each interdisciplinary module has a set of crucial skills, i.e. those regarded as key to acquire the competences defined in the teaching planning. Currently, the professors are aware that the learning of di- mensions (involving learning, learning to be, learning to live along, and learning to do) does not take place in a separated, static, and isolated way. Thus, the activities planned for con- ducting the modules seek to address these dimensions in a con- nected manner wi th regard to assessment. Different strategies and instruments are used for gathering Open Access 71  M. L. GARANHANI ET AL. information on student’s performance, such as: oral and written tests; seminars; practical tests; summaries; clinical case reports; reviews; portfolio; record of field observations; internship; among others. In the dimension named learning to do, the professors seek to combine, mainly, theory to practice and knowledge on the basic and clinical areas to findings from the classroom, labora- tory, practical field, and internship. Instruments such as a check list of performance have been useful to assess activities, pre- venting the skills required to a certain activity to be neglected. In the dimensions named learning to be and learning to live along, student’s assessment by the professor, self-assessment, and peer review have been used to help developing skills con- sistent with the professional profile required. We believe to be moving towards an integrated assessment, i.e. continued and procedural, appreciating the professor-stu- dent relationship, in order to fill in the remaining gaps between intentions expressed in the political and pedagogical project and the reality constituted by the context where the education prac- tice takes place and our individual actions. Collegiate Management We emphasize that, for developing the integrated curriculum, collective work, cooperation between the course collegiate, the department managers, the managers of the Center for Health Sciences of the university and those of other centers involved in the nursing course have been crucial, as well as the support provided by many supporting agencies, such as its library, the interdisciplinary laboratories of nursing and informatics, among others. The support provided by the Undergraduate Studies Dean’s Office and all other bodies of the institution has also been a must, helping in the academic management of the course. We also notice that the Nursing course has, over the last 20 years, developed training sections with the entire course faculty. The early ones took place between 1992 and 2000; professors from other institutions who worked on themes related to Educa- tion and Health par ticipated in them. Between 2000 and 2010, the training sections were also pro- vided, however, there was a decrease in their frequency and in the participation of professors. It is worth noticing that, within this period, a high percentage of professors sought to improve their knowledge, especially by attending Ph.D courses. Since the beginning of the school year in 2010, the course collegiate has provided pedagogical training for newly hired professors, addressing the proposal of an integrated curriculum and organizing workshops with the coordinators and professors of the modules on pedagogical techniques and tools adopted in the course. The pedagogical training of professors from other health education institutions has been conducted by means of many workshops requested by Nursing schools in various Brazilian states, over the years following the deployment of the inte- grated curriculum. This responsibility has been taken by the collegiate coordina- tion and there are professors who volunteer to carry out active- ties aimed at describing the curriculum change, sharing the pathway and explaining the strategies adopted, as well as the weaknesses and difficulties faced in the academic and peda- gogical route. For evaluating the curriculum, the Nursing course held, from 2001 to 2008, 7 Assessment Forums on an annual basis, with the participation of professors, students, and nurses working in the services of the practice fields and the course internship, as well as representatives of the organized civil society. After 2008, this event has taken place every two years. In order to promote knowledge, support, and planning, the results of this forum are shared with department managers involved in the course, the managers of the Center for Health Sciences, the Planning Dean’s Office, and the Undergraduate Studies Dean’s Office. The report of the results of these Assessment Forums, as well as the description of the processes which generated data, has contributed by providing important elements for the institu- tional assessment of the university and other scenarios that stand out due to their high quality hea lth care education. In addition to the Assessment Forums, much has been made about the experience involved in the integrated curriculum, ranging from course conclusion monographs, MS dissertations, Ph.D theses, and participation in national and international scientific events to the publication of articles, books, in short, there are many records of the education practice conducted in the institution. These experiences have allowed those involved to learn on a continuous basis about health care education in an innovative, participatory, and shared way, and it is possible to state that, in recent years, the proposal of the integrated curriculum has be- come consolidated among all professors involved in the Nurs- ing course. Final Remarks After more than a decade since the deployment of the inte- grated Nursing curriculum, we have conducted several evalua- tions and reflections about the pathway taken. We have shared situations which favor and hinder the walk. We believe that ensuring the achievement of the goals of this curriculum re- quires monitoring the progress made and the difficulties ex- perienced, as well as designing future actions. The development of a curricular project must be regarded as something dynamic, valid, useful, and effective, with an aggre- gating structure which ensures its continuity, consistency, and flexibility to take part in the contributions arising from this curricular project viewing the incorporation of news pedagogi- cal perspective in order to incorporate the new pedagogical perspectives. We may mention that the search for training a critical and thoughtful nurse concerned with facing the population’s health care needs is an ongoing challenge. The pursuit of integration and interdisciplinarity also constitutes a goal to be improved every day. This is so mainly due to the influx of new professors, who are not experienced with regard to the integrated curricu- lum, reinforcing the need for ongoing training of professors. Integration with health care services and the community is an- other current challenge for the university, since it depends on the commitment of many actors. The selection of contents, skills, and key competences which make up the interdisciplinary modules also constitutes a con- tinuous process for refining the curriculum. We have already advanced a lot with regard to the integration with professors from the basic areas, but this integration needs to be cared for every year, in a continuous movement. Mastering active meth- odologies and the two-dimensional assessment represents an Open Access 72  M. L. GARANHANI ET AL. existential challenge for professors and students, who have lived along, sharing knowledge, practices and feelings, and estab- lishing new teaching and learning ways. Another major challenge involves considering the profile of entering students in the Nursing course, since most of them are young women, and they often express contradictions with re- gard to their feelings about the course and career. Another relevant factor concerns the need for special strategies for the integration of students coming from Brazilian policies for in- clusion in Higher Education, such as Indian and black people, students with special needs, and the students coming from pub- lic education. Since 2012, we have also dealt with the early experiences of approving students to participate in international exchange and mobility programs, due to the Science without Borders Program. This is a challenge for the course collegiate to determine the equivalence between disciplines of courses attended within different contexts, as well as to allocate students coming from other countries. There is a great interest in encouraging such exchange programs, since they are opportunities to share ex- periences and foster professional and personal improvement. In addition to individual learning, we believe that all people in- volved benefit from living along with people from other cul- tures and realities. This practice brings concreteness to the con- text of a globalized world without geographical boundaries. Many advances have been consolidated with regard to infra- structure. The creation of new physical spaces, such as class- rooms, libraries, and laboratories, has supported the needs for developing active methodologies. Thus, we stress that we regard as an advance the experience itself, without denoting it is positive or negative. Some ad- vances are visible and measurable, others are not. Some are collective, others are individual. The advances are not the same for all actors involved, but, surely, each actor is no longer the same since the deployment of this curriculum. Therefore, we conclude this article highlighting some major points, however, being aware that they do not cover all ad- vances made in the construction of this curriculum. They are: collective construction; democratic and participatory process; relationship between theory and practice; diversification of teaching strategies, including complementary activities of dis- tance education; successive close approaches between the con- tents of the modules; two-dimensional assessment, comprising cognitive and attitudinal skills; pursuit of new kinds of knowl- edge or deepening of other ones in order to expand the view of the social context and its relations to the health care and educa- tion fields; use of different scenarios of professional practice as internship fields, with early introduction of the student; use of local and national reality as a reference for conducting the teaching and learning activities; and researches aimed at the pedagogical practice. Walking in the pathway of this integrated curriculum has enabled us to understand that, since it is the human being who discovers the world by means of her/his eyes, her/his interpre- tation, she/he always has the possibility of appropriating the history and constructing, sharing responsibilities and results. It is by experiencing the world of education and health care that the teaching and learning pathway is redrawn throughout pro- fessional training. We are aware that the route to follow to- wards the changes which are still needed is long and continuous. We record our experience, overtly described in this report, hoping to contribute to other Higher Education institutions trying to develop an innovative methodology. REFERENCES Almeida, M. J. (2003). National curricular guidelines for university courses in the health field. Londrina: Rede Unida. Álvarez Méndez, J. M. (2002). Evaluate to know, assess to exclude. Porto Alegre: Artmed. Ausubel, D. P., Novak, J. D., & Hanesian, H. (1980). Educational psychology. Rio de J aneiro: Interamericana. Bastos, C. C. (2006). Active methodologies. http://educacaoemedicina.blogspot.com.br/2006/02/metodologias-ati vas.html Ministry of Education (1998). National Curricular Parameters. 3rd and 4th cycles of Primary Education. Transversal Themes. Brasília: Min- istry of Education. Ministry of Health (2003). Pedagogical proposal: Evaluating the ac- tion. Brasília: Ministry of Health. Christovam, B. P., & Santos, A, I. (2004). The challenges of nurse’s management at the central health level. UERJ Journal of Nursing, 1, 66-70. Dellaroza M. S. G., & Vannuchi M. T. O. (2005). The integrated cur- riculum of the nursing course of the State University of Londrina: From dream to reality. Londrina: Hucitec. Delors, J., et al. (1999). Education: A treasure to be discovered. Report to UNESCO by the International Commission on Education for the Twenty-First Century (3rd ed.). São Paulo: Cortez . Demo, P. (1999). Mythologies of evaluation: Or how to ignore, rather than face problems. Campinas: Autores Associados. Dessunti, E. M. (2012). Contextualization of the integrated curriculum of the nursing course of the State University of Londrina. In E. M. Kikuchi, & M. H. D. M. Guariente (Eds.), Integrated curriculum: The experience of the nursing course of the State University of Lon- drina (pp. 17-32). Londrina: UEL. Dowding, T. J. (1993). The application of a spiral curriculum model to technical training curricula. Education Technology, 33, 21-30. Garanhani, M. L., Takahashi, O. C., & Kikushi, E. M. (2000). Meth- odological means for implementing the integrated curriculum of the undergraduate Nursin g c ou rse of UEL. Magic Eye, 9, 30-34. Garanhani, M. L., et al. (2012) Guiding principles of the pedagogical project of the integrated curriculum of the nursing course. In E. M. Kikuchi, & M. H. D. M. Guariente (Eds.), Integrated curriculum: The experience of the nursing course of the State University of Lon- drina. Londrina: UEL. Kikuchi, E. M., & G uariente, M . H. D. M. (2012 ). Integrated curriculum: the experience of the nursing course of the State University of Lon- drina. Londrina: UEL. Law nr. 7,498, enacted on June 25, 1986. Provides for the regulation on the nursing practice in Brazil and gives other provisions (1986). http:// jusbrasil.com.br/legislacao/128195/lei-7498-86 Official Newspaper of the Union (1990). Organic Health Law nr. 8,080, enacted on September 19, 1990. Luckesi, C. C. (2005). Philosophy of education (21st ed.). São Paulo: Cortez. Martinelli, D. D., et al. (2011). Assessment of the curriculum of the un- dergraduate course in nursing by graduated students. Cogitare Nurs- ing, 16, 524-529. Merhy, E. E. (2002). Health: The cartography of living labor. São Paulo: Hucitec. Moraes, M. C. (2010). Complexity and curriculum: For a new relation- ship. Polis, Journal of the Bolivarian University, 9, 289-311. Morin, E. (2001) The well-made mind: Rethinking reform, reforming thought (3rd ed. ). Rio de Janeiro: Bert rand Brasil. Morin, E. (2007). Introduction to complex thinking. Porto Alegre: Su- lina. Morin, E. (2010). Reconnection of knowledge: The challenge of the 21st century (9th ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil. Piconez, S. C. B. (2007). Young and adult’s learning and its key chal- Open Access 73  M. L. GARANHANI ET AL. Open Access 74 lenges. www.nea.fe.usp.br Ramos, M. N. (2001). Qualification, skills, and certification: Educa- tional view. Train in g J ou rnal, 1, 17-26. Romano, R. A. T. (2000). From curriculum reform to the construction of a new pedagogical praxis: The experience of the collective con- struction of an integrated curriculum. UERJ Journal of Nursing, 8, 78-83. Sacristán J. G. (1998). Curriculum: A reflection on practice (3rd ed.). Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas. Santomé, J. T. (1998). Globalization and interdisciplinarity: The inte- grated curriculum. Po rto Aleg re: Artes Médicas. Silva, J. F. (2004). Introduction: Evaluation of teaching and learning from a regulatory formative perspective. In J. F. Silva, J. Hoffmann, & M. T. Esteban (Eds.), Evaluative practices and meaningful learn- ing: In different areas of the curriculum (2nd ed.). Porto Alegre: Me - diação. Stefanini, M. L. R. (2004) . Editorial. Health Information Bulletin, 34. Tacla, M. T. G. M. (2002). Developing critical thinking in nursing education. Goiânia: AB Ed. |