Beijing Law Review 2013. Vol.4, No.4, 155-167 Published Online December 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/blr) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/blr.2013.44020 Open Access 155 China-Africa Legal and Judiciary Systems: Advancing Mutually Beneficial Economic Relations Moses N. Kiggundu Sprott School of Business, Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada Email: Moses.kiggundu@carleton.ca Received August 20th, 2013; revised September 23rd, 2013; accepted October 21st, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Moses N. Kiggundu. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. This paper provides a comparative longitudinal assessment of legal and judicial reforms relevant for China-Africa economic relations. It draws on and extends aspects of institutional and organizational the- ory, focusing on the concepts of convergence, alignment, hybridization, and institutional voids. Data were obtained from publically available databases from reputable international organizations including the World Bank and the World Economic Forum. Results point to areas where China has made progress more than Africa, and areas where serious capacity and performance gaps remain, especially for individual Af- rican countries. The paper provides a brief discussion of the implications for the need to build organiza- tional capacities necessary for strengthening China-Africa economic law and advancing mutually benefi- cial economic relations and concludes by identifying research limitations, and areas for future research. Keywords: China-Africa Economic Law; Regulatory Reforms; Mutual Economic Benefits; Convergence; Alignment; Hybridization; Institutions; Organizations Introduction It is generally accepted that the quality of a country’s judicial system as manifested by the rule of law, justice and respect for human and property rights, and sustainable economic develop- ment is inextricably linked. When reforms lead to economic growth and diversification, business transactions increase in volume, scope, diversity and complexity; resulting in growing demand for equally sophisticated business, legal and judicial instruments and services. However, pre-existing or traditional systems of justice are not sufficient to handle new demands. This is more so for China and Africa, both of which are under- going fundamental socioeconomic, governance and political transformations as they seek to develop and deepen bilateral and regional economic relations. Various attempts are being made on both sides to put and keep in place, judicial systems, institutions and organizations designed to provide mutually beneficial legal protections for all legitimate actors. Hong and Zhu (2009) provide a historical account of legal exchanges and cooperation between China and Africa, dating back to 1874 when Ghana, then the Gold Coast, applied Hong Kong English Law, originally enacted in 1865. The growing China-Africa relations, especially since the establishment of the Forum for China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in 2000, have stimulated interest on both sides for legal practitioners and scholars to study the legal and judicial systems, practices and reforms of the other. Although progress has been made both by China and the various African countries, challenges remain. China’s economic reforms spurred creation of new enter- prises, increased interprovincial trade, invited foreign investors, and encouraged businesses and individuals to go global and seek outside opportunities and partners including Africa. Ac- cording to Pei (2001), the expansion of business was followed by an increase in the number of cases filed in commercial courts. During the period of 1979-82, the average number of commercial disputes filed and arbitrated in the courts was around 14,000 a year; by 1997, 1.5 million new cases were filed… more than a 100-fold increase. At the same time, the number of commercial disputes arbitrated by community com- mittees, the traditional mediation mechanisms hardly increased. As the number of entrepreneurs grew the enforcement capacity of informal dispute resolution mechanisms weakened, suggest- ing the need to strengthen the country’s legal and judicial for- mal institutions. Over the same period, African countries have made serious attempts to harmonize their commercial and bu- siness laws in order to attract foreign investment. For example, in 1993, sixteen African countries established the Organization pour I’Harmonization enAfrique du Droit des Affairs (OHADA) to simplify their respective commercial legal systems, provide foreign and regional investors with simpler, modern comercial laws and enhance the settlement of commercial disputes. China has signed treaties and agreements with a number of African countries covering areas such as avoiding double taxa- tion (Mauritius), tax evasion (e.g. South Africa), investment promotion and protection (e.g. Nigeria, Tunisia), and commer- cial and judicial technical assistance (e.g. Egypt). The Chinese government and investors would like to see more legal and judicial harmonization among African states, especially using established regional trade blocs such as the Economic Commu- nity of West African States (ECOWAS), Southern Africa De- velopment Community (SADC), East African Community (EAC), and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Af- rica (COMESA) because this would reduce transaction costs, and enhance Chinese confidence in Africa as a safe place to  M. N. KIGGUNDU invest and do business. China promotes greater legal and judi- cial exchanges and collaboration with Africa on a range of is- sues including protection of international commercial transac- tions, civil and criminal technical assistance, antiterrorism, hu- man rights, combating corruption, illicit transfer of funds, and arbitration of commercial disputes (Pei, 2001; Yelpaala, 2006; Zhu, 2009). This requires fundamental reforms on both sides: strengthening institutions and organizations, simplifying pro- cedures, reducing transaction costs, and improving domestic competition and global competitiveness. The purpose of this paper is to undertake a comparative lon- gitudinal assessment of China and Africa’s legal and judicial reforms associated with China-Africa economic relations. As China and Africa rise, their respective economies grow and become more interdependent, they both require correspond- ingly sophisticated high performing legal-judicial systems to make, regulate, arbitrate, expedite and enforce rules governing economic transactions. Data are provided on Africa’s readiness to manage change in the context of globalization, capacity to achieve development outcomes, regulatory quality, and global competitiveness. Results point to areas where progress has been made, and where challenges remain. This paper is organized in five parts. The first part provides a brief discussion of the concepts of institutions and organiza- tions as they relate to China-Africa legal and judicial systems for business transactions. The second part briefly reviews cur- rent performance of China and Africa’s legal and judicial sys- tems. The third part outlines the methodology and the sources of data used for the study. The fourth and final parts provide the results and discussions thereof, respectively. The paper ends with a discussion of research limitations and points to areas for future research. Conceptual Framework The paper draws on and extends aspects of institutional and organizational theory focusing on the concepts of convergence, alignment, and hybridization as they relate to legal-judiciary systems relevant for China-Africa economic relations. Drawing on the work of others (e.g. Cooter & Schafer, 2012; the Eco- nomic Commission for Africa (ECA), 2005; Murrell, 2001; North, 1990; Trebilcock & Prado, 2012; The World Bank, 2002), institutions are defined as rules, enforcement mecha- nisms and intermediaries including behavioural norms by which agents within and outside the country interact and the organizations that implement rules and codes of conduct to achieve desired outcomes. Institutions, like organizations can be public, private or in between, but in all cases, they are highly interdependent and mutually reinforcing so that reforms or improvements in one set of institutions or organizations such as the police or commercial courts contribute to the behaviour and performance of other institutions (e.g. business enterprises). Institutions can be formal or informal, and in many countries, informal institutions are used for dispute resolution or contract enforcement within groups, including informal lenders and borrowers (see World Bank, 2002: 172) and traditional chiefs or religious leaders. In its conceptualization of the determinants of global competitiveness, the World Economic Forum (www.weforum.org) emphasizes the importance of institutions linking institutional success or failure to economic growth and business development over time and across countries. For ex- ample, government ability to legislate and improve perform- ance of the judiciary and police is related to the degree to which citizens and investors have confidence in the protection of their property and human rights. Here we see the police and the courts as manifestations of organizations rather than institu- tions. Using Solomon’s Knot as a metaphor, Cooter and Schafer (2012) explain how law can end the poverty of nations. They argue that sustained growth in developing economies occurs through innovation in markets and organizations by entrepre- neurs. Developing innovations, however poses a problem of trust between innovators who have ideas and investors who own capital. The best solution to what they call the “double trust dilemma” between innovators and investors is the law. They explain how unenforceable contracts, uncollectable debts, financial chicanery, and other legal problems stifle business ventures and cause national poverty. Using the expeditionary economics framework (expeditionary economics focuses on building and transforming economies in post-conflict nations), and drawing from various databases, Looney (2012) shows empirically that rule of law can stimulate entrepreneurship and overall economic development even for countries like Pakistan with serious governance and internal conflicts. Brock Dahl (2011) argues that in order to avoid a damaging “transition gap” similar to what happened amid regime change in Iraq and Af- ghanistan, the international community must use its leverage (e.g. Middle East opposition groups) to ensure that rule of law institutions… police, judiciary, anti-corruption, regulatory and integrity agencies… are maintained as the new governments take shape. Accordingly, the law must accommodate socially useful innovations, while weeding out destructions at an early stage (www.fauffman.og/ Thoughbook, 2011: 95). Convergence A lignm ent and Hybridiza tion Here we introduce the related concepts of institutional con- vergence, alignment and hybridization. Institutional alignment and convergence refer to the extent to which the various institu- tional performance indicators move together in the same or different directions. Specifically, convergence refers to the extent to which the relevant legal and judicial institutions and organizations for a given country improve or decline together with respect to one another and the effects on economic per- formance. If, for example all the regulatory indicators of a country are showing improvements together, this shows high levels of convergence, but if some are improving while others are not, then the legal and judicial system experiences poor convergence of the relevant institutions and organizations, which in turn impacts negatively on the overall performance of the economy. Convergence is a within-country concept. Alignment, on the other hand refers to institutional position- ing between two or more partner economies doing business together. Specifically, alignment refers to the extent to which the relevant legal and judicial institutions and organizations for the partnering economies improve or decline together over a period of reforms. For example, if the regulatory indicators of China and an African country like South Africa are showing improvements together, this shows high levels of alignment, with the expectation that the relevant legal and judicial institu- tions and organizations from both countries (e.g. the courts, police, regulatory authorities, and private law firms) will per- form well and improve bilateral economic transactions. On the other hand, if alignment is low, the institutions and organiza- tions are not moving in similar directions in terms of reform for the two participating countries, leading to poor performance Open Access 156  M. N. KIGGUNDU (e.g. dispute resolution, property rights protection, enforcing contracts, etc.). High alignment leads to bilateral reinforcement among related institutions. Unresolved disputes will be higher for countries experiencing low alignment and vice versa. Alignment is a between country concept. Writing about China’s legal reforms and protection of eco- nomic transactions, Pei advances the concept of institutional hybridization. This refers to mixed institutional forms and or- ganizational performance, which allow for practical accommo- dation to emerging political or economic interest groups and conflicting interests in society and business. Specifically, Pei found that in China, although the legal and judicial institutions have made significant improvements, they do not create “an idealized version of the rule of law” (2001: 206). Institutional hybridization is a useful concept because it addresses apparent contractions in the administration of justice in many reforming countries such as China and Africa. Such contradictions include: 1) Serious problems of corruption coexisting with the capacity for fair adjudication; 2) Allowing both administrative and judi- cial interventions in the resolution of commercial disputes; 3) The existence of ambiguity and uncertainty in the judicial sys- tem, while at the same time there is predictability and clarity; 4) Apparent political interference coexisting with assertive judicial independence, and 5) Gradual evolution towards the ideal, with incidents of primitive practices. These observations are important for reforming countries such as China and Africa because they show that reforms are not linear, but path dependent; follow a rather zigzagging, evo- lutionary and unpredictable path. They also support the idea advanced here of differentiating institutions from organizations. Organizations provide the platform for institutional norms and performance and only by understanding organizations can we explain the apparent contractions associated with institutional hybridization. Pei supports North’s theory of the incremental nature of institutional evolution so that during the process of economic or governance reforms, legal institutions and organi- zations, even when they have been historically weak, can re- spond to emerging demands of a changing socio-economic environment. Hybridization impedes the development of effi- cient markets and is characterized by variability and unpredict- ability in system performance, thus provoking anti-establish- ment activism. Alignment and convergence are related to institutional hy- bridization. With sustained high convergence… when the dif- ferent organizations of the legal and judicial system are all per- forming well… one would expect low incidents of hybridiza- tion. Likewise, with low convergence… when some organiza- tional aspects of the legal and judiciary system are performing well while others are not… one would expect high levels of hybridization. Between or among economic partner countries like China and African countries, a high degree of alignment would result in more effective, harmonious and mutually rein- forcing legal and judicial systems. Low convergence (within country) and low alignment (between partner countries) would produce the least desirable international transactions, with high levels of hybridization within and between countries. This was the case at the very beginning of the reform efforts for China (Chi, 2000; Redding and Witt, 2007), Africa (ECA, 2005), and elsewhere (Murrell, 2001). For example, Murrell reported that when the police are weak and the law courts are not independ- ent, they tend to be biased against foreign firms, an indication of low convergence. Likewise, as the legal and judicial system achieves high levels of convergence, strengthening law en- forcement organizations and according the courts independence, there is a more level playing field for both the domestic and foreign firms and other economic actors (see Clement & Murrell, 2001). Khanna and Palepu (2010: 14) discuss the concepts of insti- tutions (hard and soft) and institutional voids. They define in- stitutional voids as the lacunae created by the absence of mar- ket intermediaries. In emerging economies, investors and busi- nesses suffer from institutional voids caused by poor infra- structure (physical and institutional), access to information (e.g. about creditworthiness), arbitration mechanisms (when disputes arise), and difficulties of contracting, especially with foreign partners. The two most relevant institutions and institutional voids for a country’s legal and judicial system and institu- tions/organizations are the adjudicators and the regulators. Adjudicators help parties to resolve disputes regarding the law and private contracts, while regulators create and enforce ap- propriate policy and regulatory frameworks. Adjudicators in- clude commercial courts, arbitrators, bankruptcy specialists, prosecutors and investigators. Regulators include both public and private agencies. While institutional voids can be a source of business opportunities (e.g. by providing services to elimi- nate lacunae), within the legal and judicial systems, they im- pede the effective and equitable performance of the relevant institutions and organizations, thereby contributing to low lev- els of convergence or alignment. For example, an underfunded court system weakens the economy as well as access to the system, especially for foreign investors and businesses. In Af- rica, it is often stated that one of the impediments to private sector development is the weakness of contract enforcement because a lengthy court system is required to enforce them, resulting in excessive transaction costs and uncertain outcomes. While institutional voids are about intermediaries or lack thereof, organizational pathologies refer to system regression or deterioration manifested by poor performance at the organ- izational levels. Scott (1998: chapter 12) discusses various causes of organizational pathologies, including alienation, in- equity, and over-conformity, all of which are potentially rele- vant for understanding and reforming legal and judiciary sys- tems in China and Africa. During the early stages of system- wide reforms, organizations experience pathologies, resulting in poorer performance than before the reforms. When practical steps are not taken to reverse these trends, further reforms be- come more difficulty, as affected, often powerful interest groups mobilize for greater resistance to change. China experi- enced this during the Cultural Revolution, and African coun- tries had similar experiences following political independence and the implementation of structural adjustment programs of the 1980s. Sustainable reforms of a country’s legal and judicial system require an understanding and practical interventions designed to overcome performance problems caused by organ- izational pathologies (Kiggundu, 1989: 63-4). Revolutions like the Arab Spring are often preceded by system wide incidents of organizational pathologies; making it hard to implement prom- ised reforms such as restoring order, enforcing contracts or protecting human and property rights. While institutions define the rules of the game for actors (e.g. buyers and sellers, investors, government and contracting par- ties), organizations are the platforms for getting things done. Getting the rules right is necessary but not sufficient for the effective performance of the legal and judicial system. Al- Open Access 157  M. N. KIGGUNDU though a detailed review of the various frameworks that link institutions to organizations is beyond the scope of this paper (see Kiggundu, 1989; Mintzburg, 1979; Scott, 2008), we note in passing that building the capacity for effective and credible judicial systems in China and Africa requires dual attention to institutions and their constituent organizations. Attempting to reform institutions without corresponding attention to organiza- tional improvements result in organizational drag for the entire judicial system (ACBF, 2012). We now briefly review the per- formance of China’s and Africa’s legal and judicial systems. China’s Le g al and Judici al System for Economic Management In general, there are two legal systems in the world: Com- mon Law and Civil Law. Common Law originated in England and is widely practiced in Britain and countries of the former British Empire and possessions, including most Anglophone African countries. Civil Law, also known as the Napoleonic code, originated in Roman law and is practiced by Germany, the Scandinavian countries, and France, including most of Francophone Africa. Although China has one of the oldest legal systems in the world, present law in China is a complex mix of traditional Chinese and foreign practices; neither pure Common Law nor Civil Law. According to Redding and Witt “It would be risky to classify the system now emerging in China, except to say that it is based on a civil code, that rests on a long tradition of state control over legal process, and the absence of an independent judiciary, and that it is now incor- porating at high speed a great number of new ideas from out- side; while interpreting them into a Chinese frame” (2007: 29-30). This may explain hybridization in China’s legal and judiciary system. Institutions and related organizations are in a state of flux, with highly uncertain and unpredictable behaviour and performance. Indeed, When Deng Xiaoping started the eco- nomic reforms in 1978; China did not have much of a legal system for handling complex business transactions and disputes. The judiciary, decimated by the Cultural Revolution, was in great need of rebuilding, as was the professional legal commu- nity. China had very few qualified lawyers or legal experts. China’s impressive economic growth since the 1980s is due to “massive changes in law” Cooter and Schafer (2012: 21) because of Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, including dissolving ag- ricultural communes, restoring private business, increased pro- tection of property and human rights, contract enforcement, and replacing state-led with state-protected growth. Yet, in China, private business enterprises are predominantly owned by indi- viduals or families, rather than publically traded companies. This negatively affects the stability and strength of business organizations. Although China has adopted the limited liability form of business organization, business ownership is still pre- dominantly personal rather than public. Traditional Chinese culture requires business assets to be divided among family members when parents die. This has led to the common folk- lore that Chinese businesses are characterized by: “rags to rags in three generations” because family fortunes rise when the parent is a successful entrepreneur, they are sustained when the owner is still active or when the children are able to run the business, but fortunes begin to fall when the parent dies, chil- dren are unable or unwilling to manage the business or when family conflicts get in the way. China’s reported lack of trust beyond family and close business associates (Chen & Miller, 2010: 20), makes it hard to build an effective legal and judicial system. The attitudes and knowledge of the micro level busi- ness decision makers determine whether they use, ignore or evade the law. Lack of trust especially by powerful interest groups increases hybridization. When the formal legal system is less trusted, businesses are more likely to use informal systems or networks, and these are not always equipped to deal with more complex transactions or disputes. Indeed, property rights of a complex nature cannot simply be legislated (see Lubman, 2012; Wang, 2012). In spite of these challenges, China has made progress re- forming the legal system for business and commercial transac- tions and disputes. Pei’s data supports the view that China’s emerging legal and judicial system has assumed an increasingly important role in adjudicating economic disputes. For example, for the period 1992-96, both the number of cases and the aver- age amount of claims going through the courts significantly increased, especially for regions or provinces with larger economies (2001: Tables 6.4 & 6.5: 186-7). The data also show that during the same period, the absolute capacity of enforce- ment almost doubled. In its recent report, the World Bank ob- served that China is making progress improving business regu- lations. Since 2005, China implemented policy changes across nine areas including a new company law in 2005, a new credit registry in 2006 and, in 2007, the first bankruptcy law regulat- ing the bankruptcy of private enterprises since 1949 (World Bank: Doing Business in 2012: 9). Yet, local and regional authorities undermined these efforts because China suffers from local protectionism. This refers to the obstruction of justice by local political authorities, govern- ment agencies and law enforcement, including the police and courts, in order to protect the economic, political and social interests of the local communities. This is done for a variety of reasons including: fear that enforcement could lead to commu- nity hardship such as unemployment due to layoffs, plant relo- cation, or movement of productive assets to other jurisdictions. As well, state owned enterprises, especially Town and Village Enterprises (TVEs), owned or closely associated with local authorities, often ignore court rulings because they enjoy state protection not available to private businesses. Here we see China’s national efforts to build an effective enforcement ca- pacity for business disputes being undermined by a fragmented political system at the provincial and local levels, resulting in low convergence and higher incidents of hybridization, making it difficult to build a harmonious society as recently suggested (World Bank, 2011). Internationally and across borders, there is evidence to sug- gest that China’s legal and judicial system has not been effec- tive in regulating individual and corporate behaviour. Recent studies of illicit financial flows from various developing coun- tries (Kar & Curcio, 2011), Transparency International’s Bribe Payers Index (www.transparencyinternational.org/bribepayersindex), and the international use of legal structures to hide stolen assets abroad (Willebois et al., 2011), all point to serious problems. For ex- ample, according to Kar and Curcio, during the period 2000- 2009, China lost an estimated US$ 2.2 trillion of illegal capital flight by individuals and businesses, mostly from trade mis- pricing, rather than balance of payments. Corrupt people in China and Africa use “corporate vehicles”… corporations, foundations, trusts… to hide assets, transfer or receive funds, conceal their involvement in illegal international transactions, Open Access 158  M. N. KIGGUNDU and make it all look legal (Willebois et al., 2011: 2). Regarding the propensity for corporations to pay bribes overseas, for the period 2008-2011, executives surveyed from different countries reported Chinese companies as the second most likely to pay bribes behind Russia (see Bride Payers Index Scores 2008-2011, Appendix C: p. 28). Results show that some industrial sectors are more vulnerable to bribes than others. Construction, oil and gas and mining were reported as the most vulnerable sectors for paying bribes. As it turns out, these are the sectors where Chinese enterprises, both state and private are most active internationally, especially in Africa. Africa’s Legal and Judicial Systems for Economic Management Like China, Africa is experiencing rapid economic growth, thus giving rise to increased demand for a better functioning legal and judiciary system. Unlike China, however, Africa is not a single country, and so there are differences in the efforts and progress different countries have experienced in reforming their systems and building effective institutions and organiza- tions. In addition to different traditional forms of legal systems, most African countries adopted the systems inherited from the former colonial rulers. Former French colonies use the French civil code, while those from the former British Empire take, as their starting point, English Common Law. As these countries undertook economic reforms and took steps to stimulate the economy and attract foreign investment, they looked for ways to reform their respective business and investment laws (Hong & Zhu, 2009; Mancuso, 2008; Yelpaala, 2006), with varying degrees of success. In addition to the reform of regulations designed to improve the investment climate , as documented by the annual report of the World Bank’s Doing Business, coun- tries have attempted to introduce the Model Law, OHADA, arbitration, bilateral investment treaties and investment promo- tion and protection agreements with China and other foreign governments. In 2005, ECA; (www.uneca.org) published the Africa Gov- ernance Report 2005, which, among other things, provided a detailed assessment of the state, capacity, and performance of the legal and judicial systems of Africa as a whole, and select African countries. The report observes that in virtually every African country, access to justice in a quick and efficient man- ner is problematic. The court system is slow and expensive, and access to it is often determined by the social status of the person or persons involved. Despite constitutional guarantees in many African countries, there is wide-spread perception among citi- zens that the judiciary is only partially independent. In most African states, laws and arrangements for enforcing business contracts are part of the law of contract. Yet, the laws of con- tract have not been amended to take into account changes made by the former colonial powers, much less the new circum- stances and requirements of the reforming state and economy. Consequently, the laws on the books do not provide adequate guidance to judges, prosecutors and others responsible for the administration of justice, obliged to depend for their decisions on case law, especially in the case of Commonwealth countries, when faced with gaps or contractions in the law. The report provides illustrations from different countries. The average waiting time to get justice in court in Kenya is three years. In Egypt, the commercial legal system is so slow that in the mid1990s, the rate of resolution of commercial dis- putes was estimated at 36 percent. In Mauritius, although en- trepreneurs can go to court in case of breach of contract, in practice, the route is so tedious, costly and uncertain that most prefer to resort to arbitration, using the Convention on the Execution of Foreign Arbitration Awards, to which the country has been a party since 1931. In Zambia, limited access to jus- tice is accounted for by ineffective and poor capacity of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecution (DPP), which is underfunded, understaffed and lacks suitable accommodation, and modern office equipment, including ICT (information tech- nology and software). The report added that the office of the DPP relied on the magistrate courts and police prosecutors, many of whom are not trained lawyers, to prosecute cases, thus undermining the quality and performance of key institutions and organizations charged with the administration of justice. However, the report also reported countries where progress had been made. For example, in a sample of experts in Namibia, 96 percent reported that the country’s judiciary was fully or largely independent, compared to 70 percent for Egypt, 35 per- cent for Mali, and only 22 percent for Cameroon (ECA, 2005: Figure 7.3; p. 204). It recommends that in order to make pro- gress in enforcing business contracts in Africa, several capacity building initiatives must be taken, including: 1) updating and upgrading laws to reflect current needs and realities, 2) reduc- ing the delay, cost and uncertainty involved in accessing the courts, and 3) overhauling the judicial system to make it more efficient, transparent, and accountable (ECA, 2005: 110). These results were confirmed by earlier studies of the reform of Afri- can institutions by Kayizzi-Mugerwa (2003), and Willborg (2002) who found that most African countries have low quality legal systems of institutions, which explains poor performance of the financial sectors. The work on illicit financial transfers (Kar & Cartwright- Smith, 2010), the use of legal structures to hide stolen assets (Willebois et al., 2011), and Transparency International’s Bribe Payers Index is relevant for assessing Africa’s legal and judicial systems. Kar and Cartwright-Smith, in a study of illicit finan- cial flows from Africa, reported that for the 39-year period 1970-2008, Africa may have lost close to US$1.8 trillion. This amount has not only grown on a decennial basis, but cumula- tively, it exceeds the continent’s outstanding external debt as of 2008. These illicit flows are mostly from oil, gas and resource exporting countries such as Nigeria, Angola, DRC, South Af- rica, Egypt and Algeria. These are the countries with which China has the biggest and fastest growing economic and busi- ness relations. Investigating the impact of litigation on the poor, Brinks and Gauri (2012) studied and found the courts’ rulings very much pro-poor in India and South Africa; sharply anti-poor in Nigeria. They also found that distribution rather than obligation or pro- vision cases, which force governments to change rules to im- prove access to basic rights offer most hope for the poor. These results suggest that pro-poor legal regulations are also good for business because they can lift millions out of poverty and enlarge the domestic consumer market. Methods Sample The sample for this study is made up of China (PRC) and sixteen African countries, which by 2010 had enacted and rati- fied Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITS) with China. To this we added five countries… Angola, Kenya, Mali, Tanzania and Open Access 159  M. N. KIGGUNDU Open Access 160 Zambia, because of their historic and/or growing importance to China-Africa relations. This gives a total sample of 21 African countries. Together, these countries represent by far the largest percentages of China-Africa economic relations… trade, in- vestments and migration (Bodomo, 2010; Kiggundu, 2008). These countries are grouped according to their regions or trade blocs (e.g. ECOWAS) so as to provide a basis for comparisons with China, within and among regions. This is because China prefers to work with African regional and sub-regional group- ings. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), bilateral investment treaties are agreements between two countries for the reciprocal encour- agement, promotion and protection of investment in each other’s territories by companies based in either country. These treaties cover areas such as definition and scope of investment, admission and establishment, national, most favoured nation (MFN), fair and equitable treatments, compensation in the event of expropriation or damage to the investment, guarantees of free transfers of funds, and dispute settlement mechanisms, both state to state, state to private investors, and between or among private parties (http://www.unctadxi.org). Therefore, ratification of bilateral investment treaties is a good indicator of the seriousness with which the countries involved consider their bilateral economic and business relations, in this case between China and each of the African sample countries. Measures Table 1 provides a list of the variables and sources of data used for this study for the 2005-2012 periods. Measures are from various publically available annual databases, produced by reputable international organizations. Specifically, we draw from the World Bank’s Doing Business (BD), the World Eco- nomic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report (GCR), the World Bank’s Little Data Book on Private Sector Development, the Africa Capacity Indicators Report (ACIR), and KPMG’s country Change Readiness Index. These variables measure various aspects of the legal and judicial systems, institutions and organizations. The World Bank’s Doing Business is par- ticularly relevant because its indicators reflect the quality of business regulation in a particular economy. For example, “A fundamental premise of Doing Business is that economic activ- ity requires good rules—rules that establish and clarify prop- erty rights and reduce the cost of resolving disputes, rules that increase the predictability of economic interactions and pro- vide contractual partners with certainty and protection against abuse” (Janamitra Devan, Doing Business In 2011, Preface: v). Doing Business indicators focus on two types of measures of regulations. The legal scoring indicators such as investor pro- tections, legal rights for investors and borrowers, which reflect the quality of the laws on the books; and the time and motion indicators such as registering property, enforcing contracts, trading across borders, and the time it takes to resolve cases of business insolvency, which measure procedures, time and cost of completing transactions in accordance with the laws on the books (www.doingbusiness.org). Over time, time and motion indicators reflect actual changes (positive or negative) in the behaviour and performance of the legal and judicial organiza- tions and comparisons with partner countries. From the Global Competitiveness Report, we are interested in institutional measures of property and intellectual property protections, ju- dicial independence, efficiency of the legal framework in set- tling business disputes, efficiency of legal framework in chal- lenging regulations, and reliability of police services (www.weforum.org). From the Little Data Book on Private Sector Development, we get measures of the years it takes to Table 1. Measures and sources of data. Variables Sources of Data 1. Protecting investors* Doing Business: www.doingbusiness.org 2007-2011 2. Enforcing contracts** Doing Business 3. Registering property** Doing Business 4. Trading across borders** Doing Business 5. Judicial independence* World Economic Forum (WEF): Global Competitiveness Report (GCR): Pillar 1: Institutions www.weforum.org/competitiveness, 2007/8-2011/12 6. Settling business disputes** WEF: GCR: Pillar 1: Institutions 7. Challenging regulation** WEF: GCR: Pillar 1: Institutions 8. Clear definition of property rights* WEF: GCR: Pillar 1: Institutions 9. Intellectual property protection* WEF: GCR: Pillar 1: institutions 10. Reliability of police services** WEF: GRC: Pillar 1: Institutions 11. Time to resolve insolvency** World Bank: The Little Data Book on Private Sector Development www.data.worldbank.org… /data-books/little-data-book-0n-private-sector-development 2005, 2011 12. Capacity for development (overall) ACBF: Africa Capacity Indicators Report 2012 www.acbf-pact.org/aci 13. Change readiness index (overall) 2012 Change Readiness Index www.kpmg.com/Global/en/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublications?change-readiness-index.pdf Note: *Legal Scoring Indicators; **Time & Motion Performance Indicators.  M. N. KIGGUNDU resolve insolvency cases. From the ACBF, we get the overall measure of a country’s capacity to achieve development out- comes. KPMG’s Change Readiness Index measures the ability of the country’s public and private sector organizations to manage change for socio-economic development in the context of globalization by taking advantage of emerging opportunities, adapting or mitigating against local and global risks (www.weform.org/docs/WEF_Globalrisks_Report-2012-pgf, p. 3). Results Regulation, Competitiveness, Change Readiness and Development Capacity Table 2 provides a general profile of China and the twenty one African countries, organized by regional economic com- munities of ECOWA, SADC, North Africa, and others. The Table also provides current (2011-2012) comparative perform ance data on measures of regulatory quality (Doing Business), Table 2. Study sample general assessment: Regulatory quality, competitiveness, development capacity and readiness for change. Economies Regulatory Quality DB 2010-11 Rankings & Quadrants, N = 183 Global Competitiveness GCR 2010-11 Rankings & Quadrants, N = 139 Capacity for Development ACIR: 2012, N = 42 Change Readiness Index: Quadrants and Overall Rankings KPMG: CRI; N = 60 China 2nd (79) 1st (27) na 1st (13th) ECOWAS Cape Verde 3rd (132) 4th (117) Medium (14th) Na Ghana 2nd (67) 4th (114) High (1st) 2nd (18th) Nigeria 3rd (137) 4th (127) Medium (6th) 3rd (|39th) Mali 4th (153) 4th (132) Medium (7th) 3rd (35th) Senegal 4th (152) 3rd (104) Medium (12th) 3rd (36) SADC Angola 4th (163) 4th (138) Very Low (38th) Na Madagascar 4th (140) 4th (131) Very Low (42nd) Na Mauritius 1st (20) 2nd (55) Very Low (40th) Na South Africa 1st (34) 2nd (54) Low (28th) 2nd (26th) Tanzania 3rd (128) 4th (113) Low (16th) 4th (53rd) Zambia 2nd (76) 4th (115) Medium (8th) 2nd (|20th) Zimbabwe 4th (157) 4th (136) Medium 9th) 4th (58th) North Africa Algeria 3rd (136) 3rd (86) na 2nd (17th) Egypt 3rd (94) 3rd (81) na 3rd (41st) Morocco 3rd (114) 3rd (75) Low (18th) 1st (6th) Tunisia 2nd (55) 1st (32) na 1st (2nd) Others Equatorial Guinea 4th (164) na na na Ethiopia 3rd (104) 4th (119) Medium (4th) 4th (55th) Gabon 4th (156) na Medium (13th) Na Kenya 3rd (98) 4th (106) Medium (2nd) 2nd (28th) Sudan 4th (154) na na na Doing Busi ness 2011: (www.doingbusinessin.org); Sample divided into 4 equal quadrants: Ranks 1 - 45, Quadrant 1; 46 - 91, Quadrant 2; 92 - 137, Quadrant 3; 138 - 183, Quadrant 4; (e.g. China is in second Quadrant, 79th ranking). GCR 2011:12 (www.weforum.org); sample divided into 4 equal quadrants: Ranks 1 - 35, Quadrant 1; 36 - 70, Quadrant 2; 71 - 105, Quadrant 3; 106 - 139, Quadrant 4, N = 139, na = not assessed. ACIR 2012 (www.acbf-pact.org): 42 countries; Maximum value = 100 points; 0 - 20 very low; 21 - 40 low; 41 - 60 medium, 61 - 80 high; 81 - 100 very high; Ghana (1st) rank out of 42; na, not assessed. 2012 CRI sample of 60 countries. Open Access 161  M. N. KIGGUNDU global competitiveness (GCR), KPMG’s Change Readiness Index (overall, CRI), and for African countries, the Africa Ca- pacity Indicators (ACI). Rankings from Doing Business were divided equally among four quadrants from the top to the last. For China, the comparative data show that over the 2006-2011 period, the rankings hardly changed… 78th to 79th, although the absolute scores may have improved for the same period (DB does not provide individual scores). China improved by moving from the 3rd to the 2nd quadrant over the same period. While China performs better than any African country in the sample for global competitiveness (rank 27th), it is not always the best. For example, on regulatory quality, China ranks 79th, lower than Mauritius (20th), South Africa (34th), Ghana (67th), Tunisia (55th), and Zambia (76th). On ACI, Ghana ranks 1st on overall capacity for development, while surprisingly, South Africa ranks low at 28 out of a total of 42 African countries. Looking at the regional breakdown, overall, North Africa per- forms better on regulatory quality and global competitiveness (no data on ACI). The ECOWAS countries represented in the sample seem to do better than those in the SADC sample on ACI, but both regional blocs are low (4th quadrant) on global competitiveness. Overall, these preliminary findings suggest that most of the African economies studied are challenged by poor regulatory quality, global competitiveness, capacity for development and managing change. They also show variations within the sample, suggesting potential challenges of high in- cidences of hybridization and low convergence as defined above. These results are presented below in more details. Table 3 provides five year (2007-2011) longitudinal and comparative data of six time and motion measures of business Table 3. Comparing China and Africa: Time and Motion Measures of Business Regulation and Facilitation: FYC 07-11 (Five Year Change). Economies Rankings Efficiency Settling Business Disputes Enforcing Contracts Efficiency of Legal Framework Challenging Regulations Reliability of Police Services Registering Property Trading Across Borders China +12 +48 +13 +8 −17 −12 ECOWAS Cape Verde +12 +42 +19 na +18 −35 Ghana +1 +5 +12 +19 +77 −28 Nigeria −7 −31 +37 −10 −6 −9 Mali −17 +7 −2 −61 +5 +13 Senegal +17 −10 +13 −18 −16 +69 SADC Angola −16 −48 −43 na −13 −20 Madagascar −42 −47 −21 −42 0 +25 Mauritius −43 +48 +39 −65 +21 −1 South Africa +1 −42 +3 0 −22 −82 Tanzania +9 +33 +3 −1 +6 −42 Zambia +14 −35 +21 +2 +25 +20 Zimbabwe +51 −17 0 −2 +2 0 North Africa Algeria −51 −66 −4 −40 −9 −15 Egypt −12 +14 −23 −12 +48 +62 Morocco −5 +21 0 −5 −76 −13 Tunisia −4 −38 −2 −4 −100 +9 Others Equatorial Guinea na +19 na na −22 −41 Ethiopia +30 +25 +15 +30 +37 −8 Gabon Na −71 na na +17 −22 Kenya +19 −58 +43 +19 −14 +1 Sudan na +12 na na −11 +22 Source: Doing Business (DB) reports 2007-2011, www.doingbusiness.org; and Global Competit iveness Rep orts (GCR) 2007-8 to 2011-12, www.weforum.org. FYC = Five Year Change in Rankings, 2006-07 to 2011-2012; + (positive sign) = positive change (improved decline in rankings) ranks); − (negative sign) = negative change (decline in rankings); na refers to missing data (country not included in the annual report). Open Access 162  M. N. KIGGUNDU regulation and facilitation for China and the African economies. Time and motion measures, unlike legal scoring indicators, provide a more realistic assessment of organizational perform- ance. Specifically, they measure the efficiency and complexity involved in achieving the regulatory goals by recording the procedures, time and cost to complete a transaction in accor- dance with all relevant regulations from the point of the busi- ness manager or entrepreneur (see Doing Business 2011: Box 1.1. p. 1). The data, obtained from the annual reports of Doing Business and the Global Competitiveness Report, provide the net changes in rankings of each of the seven measures over the five year period for each of the countries studied. For example, China scores +12 for the efficiency of settling business disputes, which is the net (positive) improvement over the five year pe- riod. Likewise, China, scores of −17 and −12 for registering property and trading across borders, respectively, indicating deterioration in rankings over the same period. Alignment, Convergence and Hybridization The data in Table 3 provide evidence in support of align- ment or lack thereof, convergence or divergence, hybridization, institutional voids, and organization performance as they relate to business law in China and the African economies. To test for convergence, we examine the extent to which the six measures change together by showing improvements within each country. For example, China shows a moderate degree of convergence because five of the six measures show positive improvements. On the other hand, Nigeria, with only two out of six measures showing positive movements, provides evidence of low con- vergence among its legal and judicial institutions and organiza- tions for business regulation and facilitation. The data in Table 3 show that the best aligned countries are Cape Verde (4/5), Ethiopia (5/6), Ghana (5/6), and Zambia (5/6). These countries achieve convergence on the six time and motion measures. The worst performing economies include Algeria (0/6), Angola (0/6), Nigeria (1/6), Madagascar (1/6), Morocco (1/6), and Tu- nisia (1/6). For North Africa, the data suggests a possible source of public discontent due to deteriorating organizational performance. South Africa is notable by its surprisingly dete- riorating performance on significant dimensions of business law such as enforcing contracts, registering property, and trad- ing across borders (see Table 3). Next we test for evidence of hybridization, which refers to the existence of mixed institutional forms resulting in wide swings in institutional behaviour and organizational perform- ance. Like convergence, hybridization is a within country measure. Table 3 provides evidence of countries with very high improvements (positive scores) in some of the six measures and very high negative scores. Compared to China showing most improvements for enforcing contracts (+48), and worst per- formance for registering property (−17), African economies with the widest swings include Mauritius (+48 for enforcing contracts; −65 for reliability of police services); Tunisia (+9 for trading across borders, −100 for registering property), Ghana (+77 for registering property, −28 for trading across borders), and Kenya (+43 for efficiency of the legal framework to chal- lenge regulations, −58 for enforcing contracts). These results suggest that for these economies, we should expect incidents of good system performance and at the same time, experience incidents of bad or unethical behaviour and poor or even harm- ful performance. For example, in Mauritius, one would expect improved performance for enforcing contracts, and challenging regulations, but deteriorating performance for reliability of police services (see Table 3). Evidence of high incidents of hybridization (not idealized version of the rule of law). We now look at the evidence for alignment, which is a be- tween country measure of the extent to which the relevant in- stitutions and organizations change (improve) together in the same direction, thereby reinforcing one another’s behaviour and performance. Here we start with China and its major trading and or investment bilateral partners. Table 3 shows that China’s time and motion measures of business law achieve best alignment with Cape Verde, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Zambia, and poor alignment with Algeria, Angola, Madagascar, Morocco, and Tunisia. Looking at South Africa, Mauritius and Nigeria, representing China’s most favoured trading and investment partners, we see evidence of lack of alignments. South Africa scores −42 for enforcing contracts, compared to +48 for China, −12 for judicial independence, compared to +19 for China, suggesting that in these areas of business law, the two countries are moving in opposite directions. Likewise, Mauritius scores −43 for business dispute settlement, China +12, for judicial independence −75 compared to +19 for China, and −65 for reliability of police services compared to +8 for China. Again in these areas of business law, the two countries are moving in opposite directions. Likewise for Nigeria, data show lack of alignment in the areas of enforcing contracts (−31 for Nigeria, +48 for China), and reliability of police services. Lack of alignment in institutional behaviour and organizational per- formance among trading and investment partners creates prob- lems for investors, managers, entrepreneurs and citizens in general for both countries due to poor or unethical conduct. This may raise concerns of state capture by foreign powerful interests and illicit funds outflows. Finally, we look at the degree of alignment within regional economic groupings. While the data show no obvious patterns, some general observations can be made. Within ECOWAS, the best performing economies and best aligned with China are Cape Verde, Ghana, and to some extent Senegal, while the ones displaying misalignment are Mali and Nigeria. For SADC, economies showing better convergence with China are Tanza- nia, Zambia and Zimbabwe. As mentioned above, South Africa is problematic. Finally, North African countries show poor alignment with China. They all show deterioration in settling business disputes, challenging regulations, judicial independ- ence, reliability of police services, and except Egypt, register- ing property and trading across borders. These findings point to specific areas of business law in specific African countries where the Chinese need to be aware of potential challenges dealing with African business partners, and vice versa. Time and Motion Measures Compared to Legal Scoring Indicators Tables 4 ((a) and (b)), provide comparative data for time and motion performance indicators and legal scoring indicators for China and the African sample for the 2006-2011 period. Spe- cifically, for each variable, the table shows African countries performing equal or better than China, those experiencing the biggest declines and lowest rankings. Note that no Africa coun- try performs equal to or better than China on enforcing con- tracts, and twelve countries show either the biggest declines or lowest ranks, suggesting that enforcement of business contracts Open Access 163  M. N. KIGGUNDU Table 4. (a) Time and Motion Performance Indicators: Summary Results For China and Africa 2006-2011. (b) Legal Scoring Indicators: Summary Results for China and Africa 2006-2011. Indicators Equal or Better than China Most Improved Biggest Declines Lowest Rankings Settling Business Disputes South Africa Cape Verde Egypt, Tunisia Ethiopia Zimbabwe Algeria Madagascar Mauritius Angola Algeria Madagascar Enforcing Contracts None China Tanzania Cape Verde, Algeria Angola Nigeria Kenya Angola Gabon Senegal Sudan Challenging Regulations South Africa Tunisia Kenya Nigeria Mauritius Angola Egypt Madagascar Angola Mali Zambia Zimbabwe Trading Across Borders Mauritius Egypt Tunisia Senegal Egypt Madagascar S. Africa Ghana C. Verde Angola Nigeria Tanzania Registering Property Ghana Sudan Ghana Zambia Ethiopia S. Africa Tunisia Morocco S. Africa Kenya Nigeria Zimbabwe Reliability of Police Services Tunisia Senegal China Ghana Ethiopia Mauritius Mali Morocco S. Africa Kenya Nigeria Zimbabwe (a) Indicators Equal or Better Than ChinaMost Improved Biggest Declines Lowest Rankings Judicial Independence S. Africa Egypt C. Verde Tunisia China Ghana Algeria Mali Mauritius Madagascar Angola Algeria Madagascar Mauritius Protecting Investors Algeria Ghana S. Africa Egypt Tunisia Angola Tanzania Zambia Tunisia Egypt Gabon Mali Morocco Senegal Senegal Gabon Morocco Equatorial Guinea Sudan Intellectual Property (IP) Protection South Africa China Zambia Mauritius Angola Algeria Clear Definition of Property Rights South Africa Tunisia China Ethiopia Mauritius Algeria Mali Angola Algeria Madagascar Zimbabwe (a) remains a serious challenge for African countries studied. Only South Africa is equal or better than China for intellectual prop- erty protection, six countries show either the biggest declines (Mauritius, Madagascar, Mali) or the lowest rankings (Algeria, Madagascar, Angola), again pointing to challenges African countries face demonstrating effective protection of intellectual property rights compared to China, which is not world class either. Time and motion results for the 2006-2011 show evi- dence of lack of alignment between China and the African countries on various measures of business law. Legal scoring indicators compare China and Africa in terms of putting the appropriate business laws on the books (see Ta- ble 4(b)). Even here, several African countries… Angola, Madagascar (judicial independence), Gabon, Morocco, Sudan (protecting investors), Zimbabwe, Algeria (clear definition of property rights), seem to be lagging with the biggest declines and lowest rankings. Laws must be enacted by the appropriate authorities before they can be effectively enforced. The results here show that, compared to China, several African countries still need to enact laws in various critical areas of business law. Resolving Insolvency Cases One of the tests of an efficient and effective legal and judi- cial system for business is the extent to which cases involving insolvency and closing a business are dealt with quickly and inexpensively. Table 5 provides data for China and the African economies on the improvements made in terms of time taken to resolve insolvency cases between 2005 and 2011. Once again, while China shows more improvements than most African economies, reducing the time from 2.5 years to 1.7 years, most African countries show clear lack of progress over the seven year period (see Table 5). Only Zambia shows progress, re- ducing the time from 3.1 years to 2.7 years. Most countries register no improvements and a few register increased times: Nigeria, from 1.5 years to 2.0 years, and Ethiopia from 2.4 years to 3.0 years. Overall, these results may be indicative of divergent policy options, patterns of economic development and differences in the interplay of critical junctures and institu- tional drifts between China, on the one hand, and these African economies on the other (see Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012: 109; Studwell, 2013: 223). Open Access 164  M. N. KIGGUNDU Table 5. Comparing China and Africa: Changes in Time in Years to Resolve Insolvency and Closing a Business 2005-2011. Economies Time in Years 2005 2011 China 2.5 1.7 ECOWAS Cape Verde na na Ghana 1.9 1.9 Nigeria 1.5 2.0 Mali 3.6 3.6 Senegal 3.0 3.0 SADC Angola 6.2 6.2 Madagascar na na Mauritius 1.7 1.7 South Africa 2.0 2.0 Tanzania 3.0 3.0 Zambia 3.1 2.7 Zimbabwe 3.3 3.3 North Africa Algeria 2.5 2.5 Egypt 4.2 4.2 Morocco 1.8 1.8 Tunisia 1.3 1.3 Others Equatorial Guinea na na Ethiopia 2.4 3.0 Gabon 5.0 5.0 Kenya 4.5 4.5 Sudan na na Source: The Little Data book on Private Sector Development, The World Bank, various years. Summary and Conclusions This paper provides comparative longitudinal assessments of China and Africa’s judicial reforms. Conceptually, it draws on aspects of institutional and organizational theory and develops the concepts of convergence, alignment and hybridization. Data were obtained from publically available databases. Mutually beneficial China-Africa economic relations require conver- gence, alignment, but not hybridization. Results are at best mixed, especially for Africa. For Africa’s rise to sustain re- forms must be speeded up to improve legal-judicial capabilities and organizational performance. This is needed especially at the micro community, organizational and individual levels where serious performance challenges remain (ACBF, 2012; Jackson, 2012). Recently, The New York Times (September 17, 2013) reported growing tensions between China’s business interests in the oil sector and various African countries, includ- ing Chad, Gabon and Niger… countries with the lowest institu- tional alignment with China. These results have implications for China and Africa doing business together. A high degree of African alignment with China reassures Chinese investors of consistency and quality in the performance of all aspects of business law and vice versa. Hybridization increases uncertainty and risk as business part- ners are unable to predict outcomes purely on the basis of the merit of the case. This legitimizes extralegal (e.g. bribes, collu- sion, influence peddling, political interference, etc.) interven- tions as a way of hedging and managing risks, especially in large business transactions such as infrastructure biddings. In- volvement of the Chinese government… political, diplomatic, military… and its state owned enterprises (SOEs) in Africa is seen as a major contributing factor to high incidents of hybridi- zation both in Africa and in China. China has a role to play by building relations, facilitating cooperation, building confidence, and providing technical as- sistance to narrow the performance gap with its African trading and investment partners. Strategies should go beyond broad based approaches like FOCAC, and come up with much more country, institution and organization focused interventions, based on specifically identified needs. Conflict and post-con- flict countries—Angola, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique—are particularly vulnerable. A recent ACBF (2008) study of the capacity needs of Af- rica’s regional economic communities such as ECOWAS and SADC concluded that these bodies do not have the capacity, competencies or resources to fulfill their mandates, let alone building capacities for members’ legal and judicial systems. Therefore, instead of insisting on building African capacities using regional and sub-regional groupings, we propose a more modest but focused approach based on carefully selected coun- tries twinning and working together: jointly strategizing, tar- geting identified capacity gaps, sharing experiences and learn- ing together. For example, drawing on the results above, for improving the reliability of police services, Senegal (doing better), could twin with Mali, Ghana with Nigeria for register- ing property, South Africa with Angola and Madagascar for challenging regulations, and Tunisia with Algeria for settling business disputes. These bilateral micro-level undertakings are more likely to produce sustaining positive results because they are focused, targeted, easier to manage, based on identified needs on the ground, and likely to garner genuine local owner- ship and commitment. This approach is likely to yield better results than bundling aid on the basis of existing regional or sub-regional groupings. Mutually beneficial regional economic integration requires effectively functioning legal and judicial systems within Africa and with overseas trading partners such as China. In conclusion, we note that China-Africa economic relations do not exist in a vacuum. Therefore, the results of this study have wider implications in the global economy and global soci- ety, including the way South-South collaborations and multi- lateral technical assistance are conceptualized and conducted. Although Africa continues to receive most of its FDI (foreign direct investment) from the UK and the USA (Ernst & Young, 2011), most reforming African countries are also deepening Open Access 165  M. N. KIGGUNDU business and commercial relations with other emerging econo- mies such as the BRICKS (South Korea & South Africa in- cluded). For example, South Africa and Angola are deepening relations with India, Brazil and the Middle East, with similar implications for their respective legal and judicial systems for international business transactions. The international commu- nity, WTO, in collaboration with the Advisory Centre on WTO Law (ACWL) and the International Centre for Trade and Sus- tainable Development (ICTSD), provides technical assistance and helps developing countries to explore new ways of han- dling legal disputes in trade. While these and similar offsite initiatives provide a useful basic introduction to the relevant subject matter and wider networking opportunities for partici- pants, their impact and sustainability on the ground would be much more enhanced if they were followed up with the kind of focused and targeted twining arranges as proposed here. The study suffers from a number of limitations. For example, it is based on secondary data collected to serve other purposes, not necessarily specific to the study of legal and judicial institu- tions and organizations. As well, we did not have data on the actual performance of specific organizations or institutions for China or the African countries studies. Not all African countries were included in the sample, and some countries where China is deeply involved like the Cameroon, DRC, Libya, Namibia, and South Sudan were excluded. Published indicators like the ones used here have inherent conceptual, methodological and practical limitations, which future research should address. We are also mindful of the dangers poor numbers and misleading statistics contribute to the inaccurate assessment of African progress and policy development (Jergen, 2013). However, the paper offers in several places explicit and implicit testable hy- pothesis for future considerations in different settings. REFERENCES Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperit y , and poverty. London, UK: Profile Books. Africa Capacity Building Foundation (2011). Africa Capacity Indica- tors 2011: Capacity Development in Fragile States. Harare, Zim- babwe (also ACI 2012 & 2013). www.acbf-pact.org African Capacity Building Foundation (2008). A Survey of the capacity needs of Africa’sregional economic communities. Harare Zimbabwe. Brinks, D. M., & Gauri, V. (2012). The law’s majestic equity? The distributive impactof litigating social and economic rights. World Bank, Development Research Group, Human Development and Pub- lic Services Team, Policy Research Working Paper WPS5999. Also see Free Exchange: The law and the poor. The Economist (print edi- tion). Chen, M., & Miller, D. (2010). West Meets East: Toward an ambicul- tural approachto management. Academy of Management Perspectives, 24, 17-24. Chi, F. (2000). Reform determines future of China. Beijing: Foreign Language Press. Clement, C., & Murrell, P. (2001). Introduction. In P. Murrell (Ed.), Assessing the value of law in transition economies (pp. 1-19). Ann Arbour, MI: The University of Michigan. Cooter, R. D., & Schafer, H. (2012). Solomon’s Knot: How law can end the poverty of nations. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. Dahl, B. (2011).Closing the transition gap: The rule of law imperative in stabilizing environments. Small Wars Journal. www.ey.com Economic Commission for Africa (2005). Africa governance report 2005. Ethiopia Addis Ababa. www.uneca.org Ernst & Young (2011). It’s time for Africa: Africa’s attractiveness survey. www.ey.co m Jergen, M. (2013). Poor numbers: How we are misled by African de- velopment statistics and what we can do about it. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Hong, Y., & Zhu, W. (2009). China-Africa legal exchange and coop- eration: The past, present and future. In Liu H. W., & J. M. Yang (Eds.), Fifty years of Sino-African cooperation: Background, pro- gress & significance (pp. 263-369). Yunnan University Press. www.cucas.edu.cn/Yunnan Jackson, T. (2012). Post colonialism and organizational knowledge in the wake of China’s presence in Africa: Interrogating South-South relations. Organization, 19, 181-204. Kar, D., & Cartwright-Smith, D. (2010). Illicit financial flows from Africa: Hidden resource for development. Washington, D.C.: Global Financial Integrity. www.gfip.org Kar, D., & Curcio, K. (2011). Illicit financial flows from developing countries: 2000-2009 update with a focus on Asia. Washington, D.C.: The Global Financial Integrity. Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. G. (2010). Winning in emerging markets: A road map for strategy and execution. Boston: Harvard Business Press. Kayizza-Mugerwa, S. (2003). Reforming Africa’s institutions: Owner- ship, incentivesand capacities. New York: United Nations University Press, Kiggundu, M. N. (1989). Managing organizations in developing Coun- tries: An operational and strategic approach. West Hartford: Kume- rian Press. Kiggundu, M. N. (2008). A profile of China’s outward foreign direct investment. Proceedings ofthe American Society of Business and Behavioural Scienc e s, 15, 130-144. Looney, R. (2012). Entrepreneurship and the process of development: A framework for applied expeditionary economics in Pakistan. Kau- ffman Foundation Research Series. Lubman S. B. (2012). The evolution of law reform in China: An uncer- tain path. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Edgar. Mancuso, S. (2008). The harmonization of commercial law in Africa and itsadvantages for Chinese investment in Africa. Macao: Univer- sity of Macau Institute for Advanced Legal Studies. Mintzberg, H. (1979). The structuring of organizations. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall. Murrell, P. (2001). Assessing the value of law in transition economies. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press. New York Times (2013). China finds resistance to oil deals in Africa. www.nty.com North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pei, M. (2001). Does legal reform protect economic transactions? Commercial disputesin China. In P. Murrell (Ed.), Assessing the value of law in transition economies. University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbour. Redding G., & Witt, M. A. (2007). The future of Chinese capitalism. New York: Oxford University Press. Scott, R.W. (1998). Organizations: rational, natural and open systems (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Scott, R. W. (2008). Institutions and organizations: Ideas and interests (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Studwell, J. (2013). How Asi a works: Success and failure in the world’s most dynamic region. New York, NY: Grove Press. Transparency International (2011). Bribe payers index 2011. www.transparencyinternational.org Trebilcock, M. J., & Prado, M. M. (2012). What makes poor countries poor? Institutional determinants of development. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Edgar. Wang, J. Y. (2012). Company law in China: Regulation in business organizations in a transition economy. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Edgar. Wihlborg, C. (2002). Insolvency and debt recovery procedures in eco- nomic development: An overview of African law. Discussion Paper No. 2002/27, UNI/WIDER. Willebois, E. D., Halter, E. M., Harrison, R. A., Ji, W. P., Park, W., & Sharman, J. C. (2011). The puppet masters: How the corrupt use le- gal structures to hide stolen assets and what to do about it. Wash- ington, D.C.: The World Bank. Open Access 166  M. N. KIGGUNDU Open Access 167 World Bank (2011). China 2030: Building a modern, harmonious, and creative high-incomesociety. Washington, D.C. World Bank (2002). World development report: Building institutions for markets. Washington, D.C. Yelpaala, K. (2006). In search of a model investment law for Africa. Law for development review. Africa Development Bank, 1, 1-75. Zhu, W. (2009). OHADA: As a basis for Chinese investment in Africa. Recuit Penant, 119, 869. Zhu, W. (2011). Arbitration as the best option for the settlement of China-African trade and investment disputes. The Centre for African Laws and Society, Faculty of Law, Xiangtan University, Hunan Province, PRC; Paper presented at the Workshop on Africa-China Relations: Towards Sustainable Chinese Investment in Africa, The University of Hong Kong, School of Humanities, African Studies Programme.

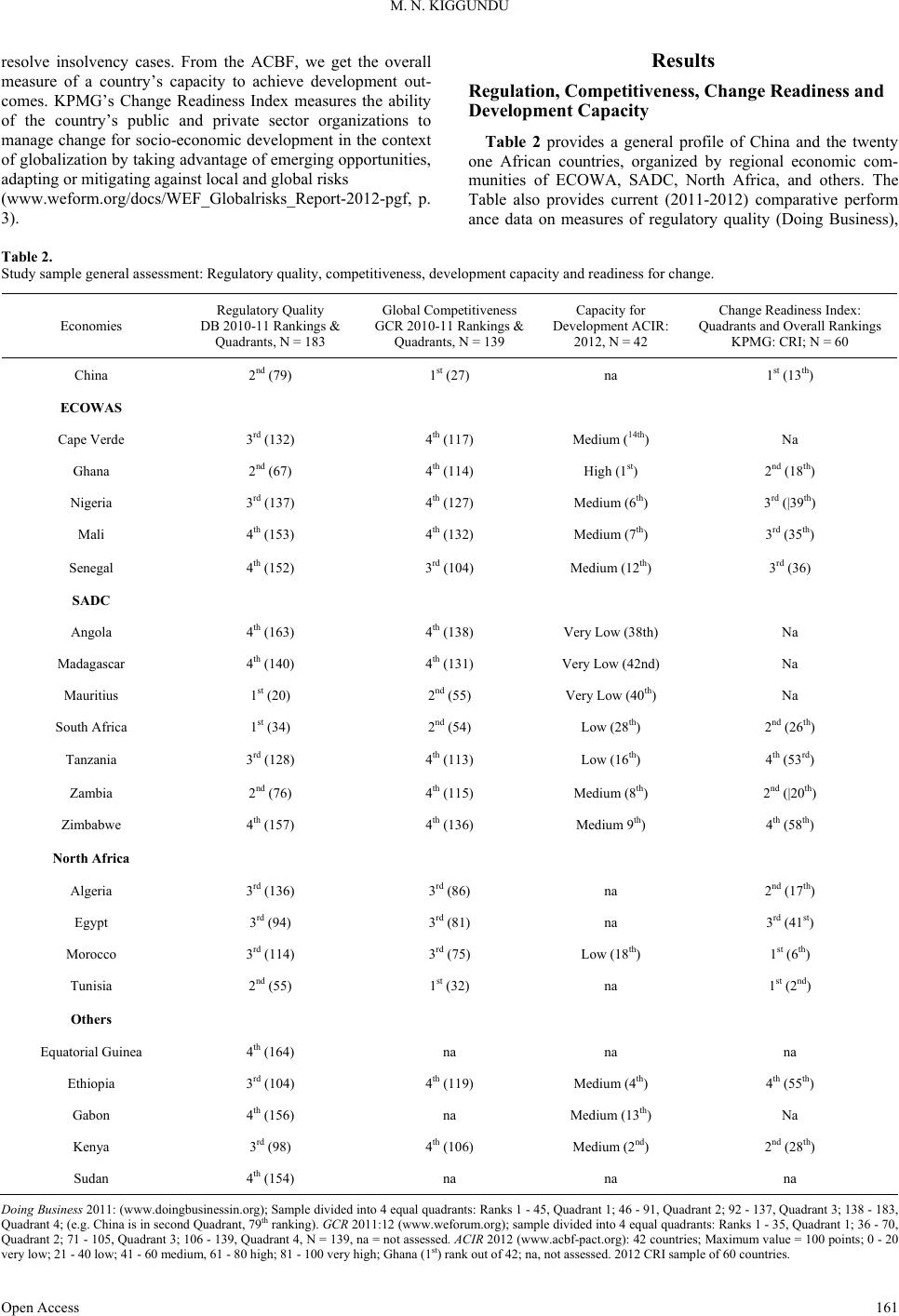

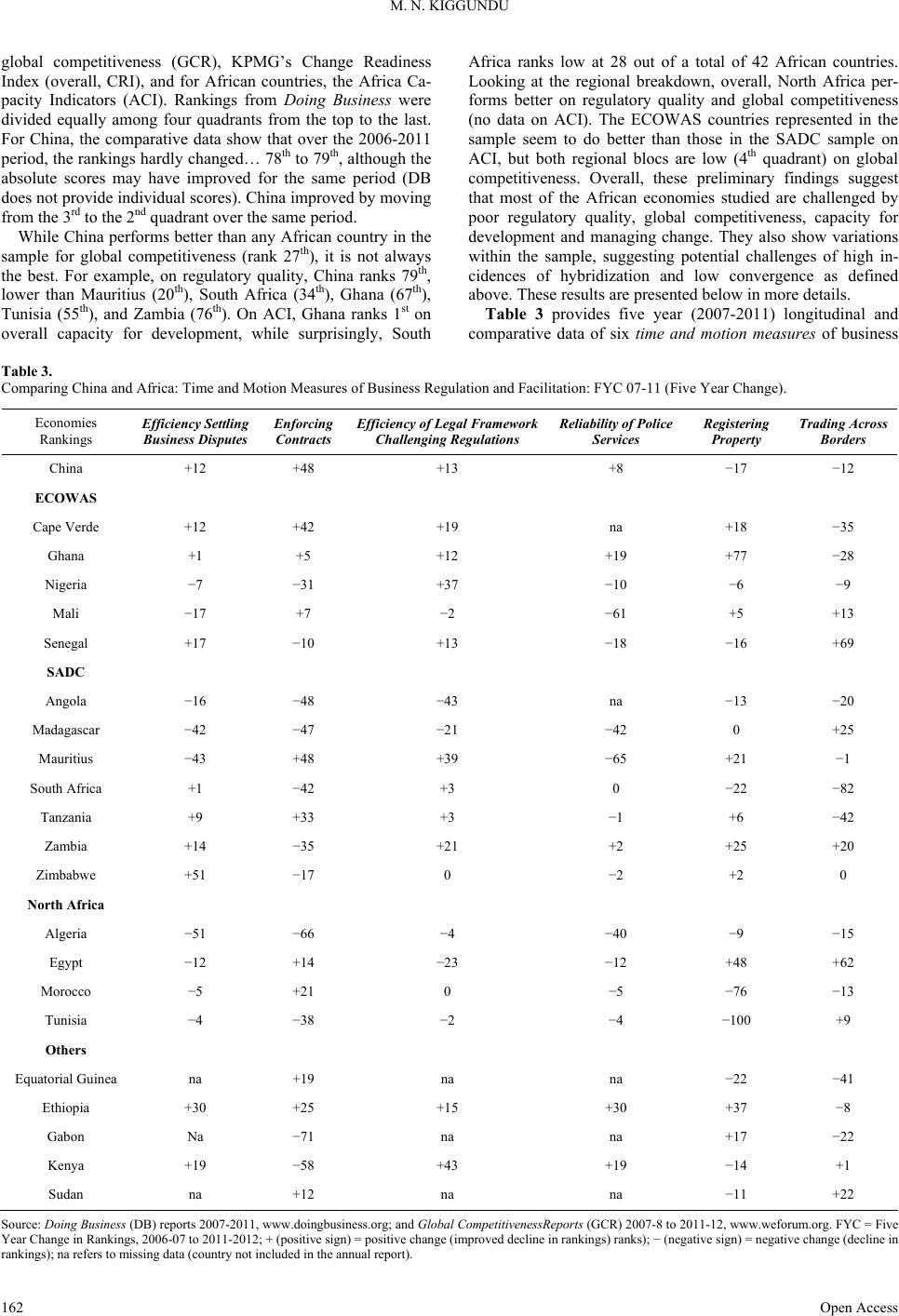

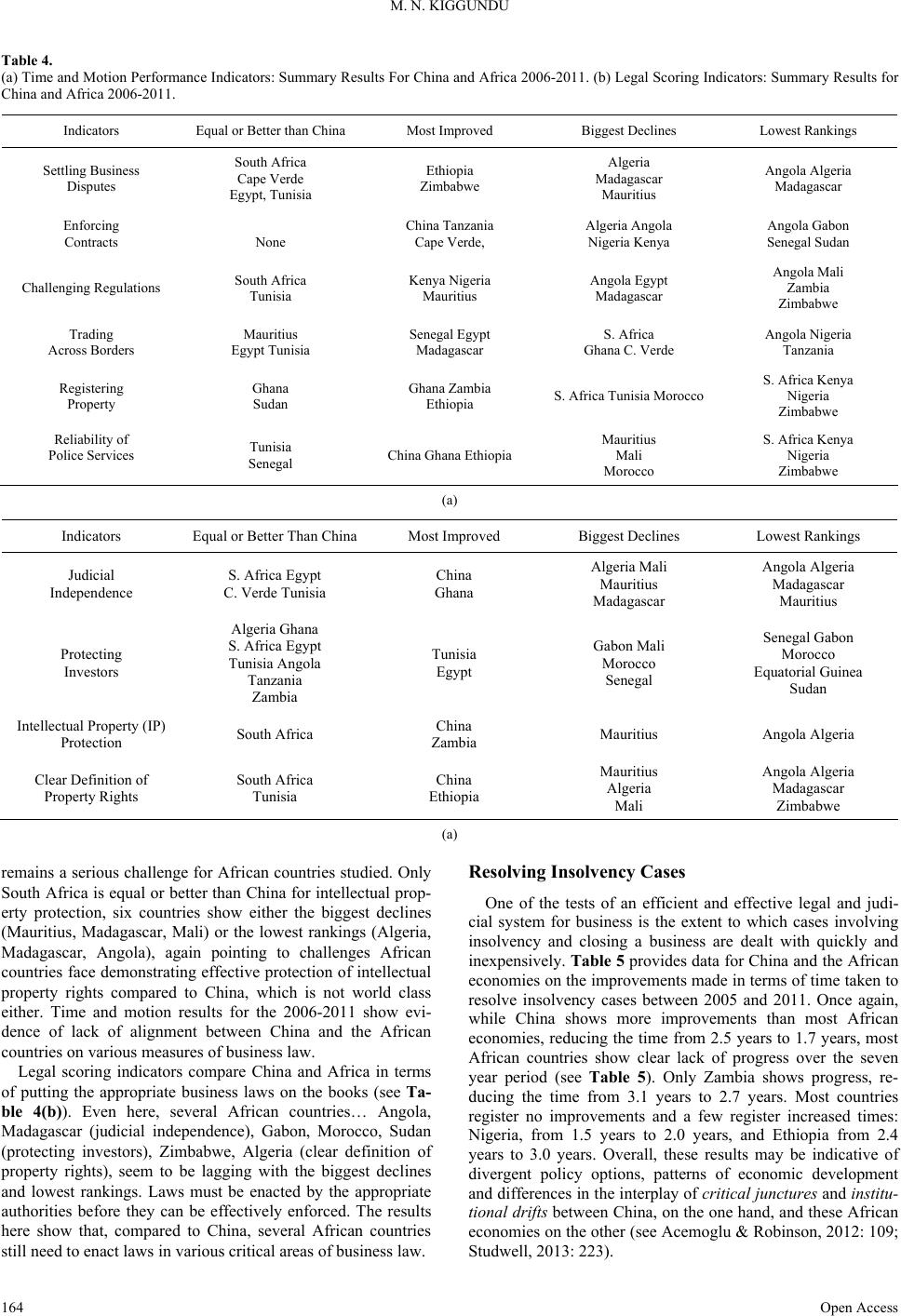

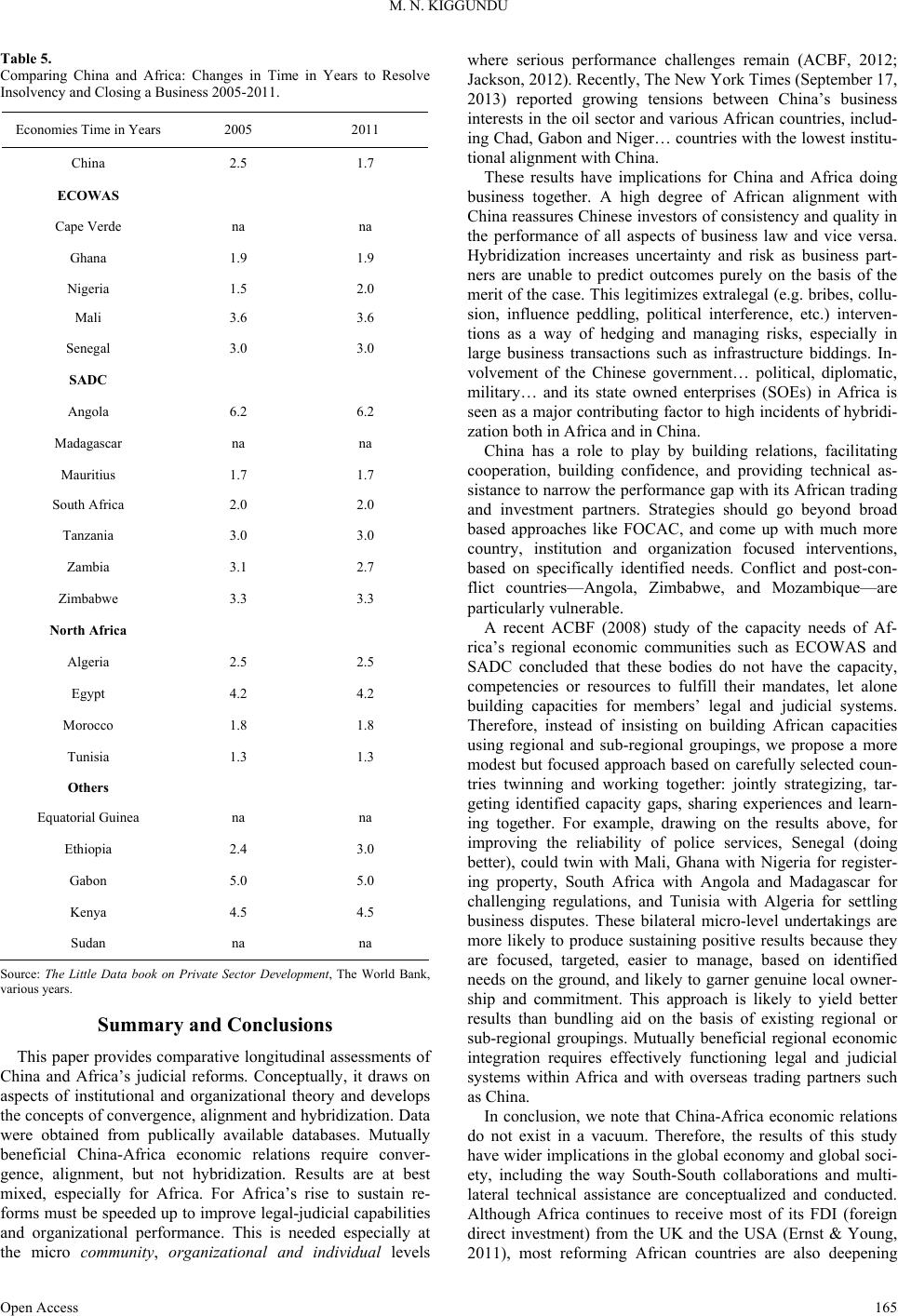

|