Advances in Applied Sociology 2013. Vol.3, No.8, 320-328 Published Online December 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/aasoci) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2013.38041 Open Access 320 Keeping the White Family Together: Racial Disparities in the Out-of-Home Placements of Maltreated Children Angela M. Kaufman Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, USA Email: kaufmaa@bgsu.edu Received September 24th, 2013; revised October 24th, 2013; accepted October 31st, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Angela M. Kaufman. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The likelihood of being removed from the home following a case of maltreatment is much higher for black youth than for whites. Two explanations exist in the literature. The first, black children experience more serious forms of maltreatment and have fewer resources to remedy the maltreatment situation than do whites. The second, there is an underlying racial bias within the child welfare system. The present study examines 789 dependency cases from child welfare services in a large urban county in the North- west United States. Using multiple logistic regression models, it examines whether race has an effect on child placement within the child welfare system, and whether the factors influencing placement are the same for white and black youth. Findings illustrate a racial disparity in out-of-home placements support- ing both of the competing explanations in the current literature. Overall, the present study finds that two separate processes seem to be at play in the placement decisions of maltreated youth, and concludes with possible explanations for this differential treatment. Keywords: Child Welfare; Child Maltreatment; Foster Care; Child Service Agencies; Out-of-Home Placement, Child Abuse; Racial Differences in Child Placement Introduction More than 3.5 million children received Child Protective Service (CPS) investigations in 2007, with an estimated 794,000 children found to have substantiated cases of mal- treatment (US Dept., 2009). While this translates into 10.6 per 1000 children experiencing maltreatment in the population overall, this rate varies considerably across racial-ethnic groups (US Dept., 2009). More importantly, these same disparities can be seen when looking at the intervention decisions concerning the maltreated child, where studies show that children of mi- nority groups, particularly the children of black families, are placed in foster care at higher rates than children from white families (Needell, Magruder, & Putnam-Hornstein, 2007; Ri- vaux et al., 2008). Examining decision making within CPS is important, as removing maltreated children from their homes can have lifelong consequences on their ability to form bonds and attachments with others. Out-of-home placement for mal- treated children may also increase their risk for later juvenile and adult criminal offending, depending on the circumstances of their removal and placement (Ryan, Testa, & Zhai, 2008). Examining placement decisions in the earlier stages of the child welfare process, where caseworkers and judges have more dis- cretion, will also allow for the understanding of where in the process unwarranted disparities might develop. Background Two Explanations for Racial Disparities Much prior research has analyzed the causes of child mal- treatment (Barth, 2009; Barth, Wildfire, & Green, 2006; Phil- lips, Burns, Wagner, & Barth, 2004; Polansky, Chalmer, But- tenweiser, & Williams, 1981), but much less has examined the placement decisions associated with maltreatment. Especially neglected until recently is whether race and ethnicity play a role within child welfare; and findings are inconsistent among the few studies that do look at this issue. Some argue the overrep- resentation of blacks within CPS can be accounted for by dif- ferences in poverty and other forms of structural disadvantage; while others state there may be additional factors at play, per- haps racial bias, which contributes to the greater representation of black children in the system (Barth et al., 2006; Lindsey, 1994; Phillips et al., 2004; Pinderhughes, 1991). One explanation for the greater likelihood of out-of-home placement among black children is that disadvantaged locations of racial minority groups put them at higher risk for maltreat- ment, and makes the evidence of maltreatment more visible to CPS agencies (Drake, Lee, & Jonson-Reid, 2009; Knott & Do- novan, 2010). Characteristics contributing to higher levels of maltreatment and greater intervention include lower socioeco- nomic status, greater family instability, and parental health problems. These same characteristics are often viewed as more difficult to remedy through both community and official inter- ventions (Brown, 2008). However, an alternative argument is that racial disparities exist in part because of an underlying bias within the system (Hampton & Newberger, 1985; Hill, 2004; Knott & Donovan, 2010; Miller & Gaston, 2003; Osterling, D’Andrade, & Austin, 2008). This research finds that racial minorities are at no greater risk of maltreatment than are whites, even when disadvantage is taken into account. If these findings  A. M. KAUFMAN represent the true nature of racial disparity in child welfare, it is possible that part of this disparity is due to judgments based on race. The Race-Poverty Link The association between race and poverty is one of long- recognized significance. In 2007, 8.6 percent of non-Hispanic whites were declared impoverished according to national pov- erty thresholds, while 24.7 percent of blacks met such standards (National, 2007). This association, in turn, may have negative repercussions for racial-ethnic minorities in child welfare. For instance, according to Lindsey’s (1994) analysis of national survey data, parent’s income level was the major determinant in a child’s removal from his or her family. While this analysis did not focus on race specifically, economic inequalities that dis- advantage minorities prevent the informal rectification of child maltreatment once reported. Specifically, CPS agencies in 33 states in the US reported that high community poverty rates may increase the proportion of black children entering foster care compared to whites, who are much less likely to live in impoverished neighborhoods (Brown, 2008). This is because residing in poor communities oftentimes limits access to the kinds of support and services needed to both prevent and rectify child maltreatment (Rivaux et al., 2008; Schuck, 2005). Neces- sary support and services include affordable and adequate housing, substance abuse treatment, and family counseling (Brown, 2008). Mental health services are particularly impor- tant for black youth, who have been found to demonstrate the greatest level of need compared to both white and Hispanic youth, but are the least likely to receive such services (Rawal, Romansky, Jenuwine, & Lyons, 2004). Therefore, without the ability to remedy the situation in the allotted timeframe be- tween case reporting and appearing before the dependency judge, an out-of-home placement may be seen as the only fea- sible alternative in alleviating the maltreated child’s suffering. However, prior research supporting a race-poverty explanation for racial disparities in the child welfare system still finds that socioeconomic status cannot fully explain the race gap. Black children have been found to experience upwards of a 77 percent increased likelihood of home removal after such variables as household income are taken into account (Rivaux et al., 2008). The Importance of Familial Characteristics In addition to poverty, other characteristics may contribute to the racial disparity in out-of-home placements. One such char- acteristic is family structure. Poverty rates are highest for fami- lies headed by single women, particularly if they are black or Hispanic (National, 2007). Related, both Hispanic and non- Hispanic black women have more unmarried childbirths than do whites (Martin et al., 2009). This may be especially relevant in cases of neglect, which instead of being malicious is often the unfortunate consequence of lacking the resources necessary to provide a healthy and safe environment for children. Simi- larly, the poor, and often racial minority, are likely to have co- occurring problems of substance abuse, arrest or incarceration, mental health problems, chronic illness, and low education (Barth et al., 2006; Phillips et al., 2004; Polansky et al., 1981). These problems increase the likelihood that such families will become involved with CPS agencies through avenues other than the maltreatment itself, supporting the possible legitimacy of racial disproportionality in CPS agencies. Understanding Disparity within the Child Welfare System as Resulti ng fr om Bias The belief that biases and discrimination are behind racial disparities in CPS agency involvement is supported by several national studies suggesting there are no racial-ethnic differ- ences in the occurrence of child maltreatment (Kirk & Griffith, 2008; Sedlack & Broadhurt, 1996). Prior studies also indicate that black families are held to different standards based on their perceived dangerousness and threat to mainstream society (Al- bonetti, 1991; Bridges & Steen, 1998; Hill, Harris, & Miller, 1985; Sampson, 1986; Tonry, 1995). Thus, differences in out- comes between black and white children in CPS may be largely due to the perception that blacks constitute a more dangerous group, even when their behaviors are similar to that of whites (Albonetti, 1991). While empirical literature on overt racism within the child welfare system is scarce, evidence from case review studies often support racial bias in child maltreatment reporting (Hampton & Newberger, 1985; Lane, Rubin, Mon- teith, & Christian, 2002). Related, some researchers and practi- tioners state that a universal set of standards is oftentimes used to evaluate families, without taking into account social and cultural diversity. As such, characteristics of poverty or single parenthood may be seen as deviant in the system if, for exam- ple, two-parent middle-class households are held as the stan- dard of a well-functioning family (Billingsley & Giovannoni, 1972; Hill, 2004; Miller & Gaston, 2003). This phenomenon is especially evident in less serious reports, where case workers and judges have greater discretion, and are thus more suscepti- ble to the practice of differential response (Osterling et al., 2008; Rivaux et al., 2008). Explanations for this differential response have been attributed to a variety of factors, including: black families’ abuse and neglect being seen as less remediable than white families’, black families being held to unattainable white middle-class standards, or black families suffering from the devaluation of their culture and family functioning (Billingsley & Giovannoni, 1972; Hill, 2004; Knott & Donovan, 2010). Study Significance Two main research questions guide this study. First, does a maltreated child’s race affect the likelihood of receiving an out-of-home placement? Second, do different factors matter for black and white children within the decision making process? Based on prior research, I hypothesize black children will be more likely to have an out-of-home placement than their white counterparts. However, I hypothesize that some of the race gap is explained by risky familial characteristics such as low socio- economic status, substance abuse, and mental illness that may be more common among blacks than whites. I also hypothesize that these risk factors exert a stronger effect among blacks than whites, as these characteristics may serve to reinforce beliefs about the perceived inability of black families to care for their children. They may also illustrate the possibility that the thres- hold when identifying these factors as problematic is lower for black families (Sampson & Laub, 1993; Tonry, 1995). Finally, I hypothesize that characteristics specific to maltreatment, such as the type of abuse, will matter more for white children than for black children. By controlling for characteristics associated with both racial minority status and out-of-home placement, I hope to better understand the extent to which racially-disparate outcomes in CPS are unwarranted. In doing so, this study will enable CPS and other law enforcement officials to tailor their Open Access 321  A. M. KAUFMAN response and treatment of minority groups accordingly in han- dling child maltreatment cases. Data and Measures The dataset I use to conduct this study is “Childhood Vic- timization and Delinquency, Adult Criminality, and Violent Behavior in a Large Urban County in the Northwest United States” from the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) online database. The dataset consists of children who were age birth to 11 years between 1980 and 1984, and were born in a large urban county in the Northwest United States. Data was obtained from administrative records; including birth records and county court house dependency records, as well as from the US Census Bureau for the socio- economic variables. Potential respondents were selected based on whether the child was born in the state, their maltreatment case stayed within the county during the study and they were made a dependent of the state within that county, their depend- ency record was available for data documentation, and the child was still alive, i.e. did not die as a result of maltreatment or other causes throughout the study. After these rules were ap- plied, 877 dependency petitions were included. Dependent Variable: Child placement serves as the outcome variable in this analysis and is divided into several categories: remained with parent or guardian, group home, adopted, kin care, foster care and aged out of the system. In this analysis, placement is dichotomized with an in-home placement coded as 0 and including only those children ordered to remain with their parents or guardian, while out-of-home placement is coded as 1, including all other categories, except those cases in which the subject aged out of the system. These individuals are not eligi- ble for placement and are deleted from the sample. Independent Variable: The main independent variable is the racial identification of the maltreated child. Although the origi- nal coding of this variable categorizes children as Native Amer- ican, African American, American Asian, American Pacific Islander, Caucasian, and Other classification, due to small sam- ple sizes in some of these categories, the race variable is re- coded into a white (coded as 0 for the reference category) and black (coded as 1) dichotomous variable, while all other racial- ethnic categories, 66 cases representing less than eight percent of the sample, are dropped from the analyses. Relevant Placement Factors: These include the characteris- tics of the maltreatment, as well as other disadvantageous fa- milial characteristics that could be detrimental to the child’s well-being, regardless of whether the maltreatment alone war- rants home removal. These are important to take into account, as prior research claims that it is both abuse characteristics and other co-occurring issues that account for the higher representa- tion of black children within the system (Barth, 2009; Burns et al., 2004; Courtney, McMurtry, & Zinn, 2004). Maltreatment Type: The measure of maltreatment type differentiates between four major types of maltreatment: physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect, as well as a fifth category of multiple abuse types which encompasses those children who have experienced any combination of two or more types of the major maltreatment categories. These five categories of mal- treatment will be dichotomized into a 0, 1 coding, indicating which type of maltreatment each subject experienced. Sibling Victimization: Whether another child is being victimized in the home demonstrates the overall safety of the home environment, as well as the likelihood that the subject may suffer further maltreatment. Sibling victimization is dichotomized into a 0, 1 coding, signifying whether a sibling of the subject has also suffered from abuse or neglect. AFDC: Poverty has been cited as a main consideration in removing a child from the home (Barth, 2009; Lindsey, 1994; Rivaux et al., 2008; Schuck, 2005) and is highly correlated with racial-ethnic status (National, 2007). As such, in this analysis, Aid to Families with Depend- ent Children (AFDC) payments will be used as a proxy for the measurement of parental socioeconomic status. The variable AFDC reports the percent of families receiving such payments in the subject’s birth census tract based on the 1980 census, and is a continuous measurement at the census tract level. Parental Health: Parental mental illness and substance abuse are impor- tant characteristics to take into account as they contribute to the possible instability of the home environment, and have been found in prior research to be correlated with racial minority status (Barth et al., 2006; Phillips et al., 2004). Both of these measures are dichotomized into a 0, 1 coding, signifying whe- ther the parent(s) displays such characteristics when the mal- treatment case comes before the dependency judge at the initial court hearing. Behavioral Problems: An estimated 19 percent of children in the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NCSAW) entered out-of-home placement, even though they did not have obviously unfit parents. This was suggested to have occurred due to the multitude of emotional and behavioral difficulties the child was dealing with (Barth et al., 2006). Child behavioral problems are dichotomized into a 0, 1 coding, signifying whether the child displays such charac- teristics when the maltreatment case comes before the depend- ency judge at the initial court hearing. Demographic Controls: Both the gender and age of the child are controlled for in this analysis. Gender is highly correlated with some types of abuse, specifically sexual abuse, which females experience at a much higher rate than males (Widom & Maxfield, 2001). In regard to age, NCANDS data illustrate (Wulczyn, 2009) that younger children may be at a higher risk for both the actual occurrence of maltreatment, as well as it being reported. This finding can be extrapolated to the place- ment of the child, in that younger children may be perceived as having a higher risk for subsequent victimization. Gender will be dichotomized, with male coded as 0 for the reference cate- gory, while age is measured using a continuous variable. Analytic Strategy The original data sample is restricted in three ways for this study’s analyses. First, when looking at the selected variables for this analysis, the data completeness report shows that only one of the 877 treatment cases is missing. Therefore, this one individual will be dropped from the analysis. Second, those subjects falling into racial categories other than white and black are excluded. Finally, those subjects that aged out of the system between their maltreatment report and appearing before the judge at the initial dependency hearing are dropped from the analyses, as they are not eligible for a placement decision. These restrictions result in a total sample size of n = 789, with 598 white and 191 black children. With these restrictions in place, I will first examine descriptive statistics focusing on differences between black and white children on the dependent variable and important risk factors. Second, I will use logistic regression to examine the differences for placement outcomes Open Access. 322  A. M. KAUFMAN Open Access 323 of the maltreated children. In a series of nested models, I will analyze what relevant risk and demographic factors are associ- ated with placement decisions and the extent to which they account for any black-white differences. In the first set of ana- lyses, a total of five nested logistic regression models will be used for the full sample of maltreated children, regressing the placement decision on the key independent variable, race, de- mographic controls for the child, and other relevant risk factors related to both the child and parents generally, as well as the maltreatment situation specifically. In the second set of analy- ses, the full model will then be partitioned into two separate models by race. Z-tests for coefficient differences will be per- formed to examine if the risk factors have different effects for black and white children within the child welfare process. Results Descriptive Statistics In Table 1, I provide descriptive statistics for all variables in the analysis. I show the characteristics of the total sample (n = 789), and for the separate white (n = 598) and black (n = 191) samples. Also, I provide results of 2 and t-tests to denote characteristics where white and black youth differ. Most nota- bly is the significant difference in the dependent variable, placement. About 74 percent of black children are ordered out of the home, compared to only about 46 percent of white child- ren. However, black and white children vary little on many relevant placement characteristics, including gender, age, pa- rental substance abuse and parental mental illness, childhood behavioral problems and physical abuse as the maltreatment type. Risk factors that are more common among black children include AFDC (15.0% versus 7.0%), and maltreatment types of neglect and emotional abuse (39.3% versus 30.4%, and 16.8% versus 6.9%, respectively). Relevant risk factors that are more prevalent among white children, on the other hand, include sibling victimization (17.4% versus 1.6%), and sexual and mul- tiple abuse as the documented forms of maltreatment (10.9% versus 4.7% and 42.8% versus 29.8%, respectively). Multiple Regression Models-Ordered Placement for All Maltreated Children In the next part of the analysis, I examine whether the racial disparity in the likelihood of receiving an out-of-home place- ment can be explained by those risk factors that black youth are more likely to experience than their white counterparts. Table 2 examines the relationship between race and placement for the full sample of maltreated children in a series of nested models, controlling for demographic characteristics, family risk factors and maltreatment characteristics. In Model 1, placement is regressed only on the main inde- pendent variable, race. The odds of receiving an out-of-home placement are 3.335 times higher for black children than for white. In Model 2, the age and gender of the maltreated child are entered into the equation. While the effect of age is not statistically significant, the effect of gender is. The odds of being ordered out of the home are 32% lower for girls than for boys. However, controlling for age and gender do not appear to substantially reduce the higher risk of black children being removed from the home compared to white children. In Model 3, I include the AFDC measure to examine whether socioeco- nomic status accounts for any of the racial disparity in place- ment. Consistent with findings in prior research, the effect of AFDC is statistically significant. For every percentage increase Table 1. Descriptive statistics for white and black maltreated children. Measure Total Mean White Mean Black Mean Difference Tests Out-of-home placement 52.6% 45.8% 73.8% 45.5290*** Female 52.9% 54.5% 47.6% 2.7427 Age 7.00 6.98 7.07 0.4074 AFDC 8.92 6.99 14.98 13.5239*** Parental substance abuse 24.8% 24.1% 27.2% 0.7668 Parental mental illness 16.9% 16.4% 18.3% 0.3874 Childhood behavioral problems 14.2% 15.2% 11.0% 2.1192 Sibling victimization 13.6% 17.4% 1.6% 30.9094*** Neglect 32.6% 30.4% 39.3% 5.1417* Emotional abuse 9.3% 6.9% 16.8% 16.8907*** Physical abuse 9.1% 9.0% 9.4% 0.0271 Sexual abuse 9.4% 10.9% 4.7% 6.4578* Multiple abuse types 39.7% 42.8% 29.8% 10.1695*** N 789 598 191 Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.  A. M. KAUFMAN Table 2. Ordered placement for all maltreated children. Regressor Model 1 Odds Model 2 Odds Model 3 Odds Model 4 Odds Model 5 Odds Intercept −0.168* (0.082) −0.055 (0.216) −0.220 (0.225) −0.526* (0.240) −0.132 (0.278) Black 1.204*** (0.184) 3.335 1.187*** (0.185) 3.279 0.962*** (0.201) 2.616 1.037*** (0.205) 2.822 0.877*** (0.212) 2.404 Female −0.386** (0.148) 0.680 −0.416** (0.149) 0.659 −0.179 (0.158) 0.836 −0.089 (0.163) 0.915 Age −0.014 (0.027) 1.1014 −0.010 (0.027) 1.010 −0.027 (0.029) 0.974 −0.022 (0.029) 0.978 AFDC 0.030* (0.011) 1.031 0.035** (0.011) 1.035 0.032** (0.012) 1.033 Parental substance abuse 0.382* (0.178) 1.465 0.315 (0.181) 1.370 Parental mental illness 0.497* (0.209) 1.645 0.310 (0.214) 1.363 Prior childhood behavioral problems 1.530*** (0.258) 4.618 1.416*** (0.261) 4.120 Sibling victimization −0.591* (0.242) 0.554 Emotional abuse 0.259 (0.305) 1.295 Physical abuse −0.628* (0.291) 0.534 Sexual abuse −0.860** (0.309) 0.423 Multiple abuse types −0.392* (0.278) 0.675 χ2 47.22*** 54.18** 62.07*** 110.74*** 132.60*** Psuedo R2 0.0433 0.0496 0.0569 0.1014 0.1215 Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. in the families receiving AFDC payments in the subject’s cen- sus tract, the odds of out-of-home placement increase by about 3 percent. Furthermore, the inclusion of this variable substan- tially reduces the disparity between black and white children in the odds of being ordered out of the home, from 3.28 in Model 2 to 2.616 in Model 3, a reduction of about 20 percent. How- ever, the effect of race is still statistically significant. Model 4 adds familial characteristics that may further con- tribute to disparity, as they illustrate relevant risk separate from maltreatment that may be detrimental to the child’s well-being. All three characteristics, parental substance abuse, parental mental illness, and prior childhood behavioral problems, are significantly related to being removed from the home, with increased likelihoods of 46.5%, 64.5%, and 361.8%, respec- tively. The inclusion of this additional block of variables also reduces the effect of female to insignificance. Entering the va- riables individually shows that it is the addition of prior child- hood behavioral problems that has this effect, as males are more likely to exhibit such behaviors in comparison to females. Including these three variables also slightly increases the racial disparity in out-of-home placement. Whereas in Model 3, the odds of being ordered out of the home were 2.616 higher for black children, net of other factors, this likelihood increases to 2.822 in Model 4. Again, this is due to the inclusion of prior childhood behavioral problems. Adding the variables individu- ally illustrates that parental mental illness and parental sub- stance abuse affect the coefficient for black by less than 1 per- cent, whereas prior childhood behavioral problems lead to an increase of approximately 8 percent in the race coefficient in Model 4. Put simply, despite having fewer documented behav- ioral problems, black children are still more likely to be re- moved from the home than whites, net of other factors. The final model (Model 5) illustrates that the type of mal- treatment the child experiences is a significant predictor of out- of-home placement, with children experiencing physical abuse, sexual abuse, and multiple abuse types having significantly different odds of being removed from the home when compared to neglect. Interestingly, these three types of maltreatment actu- ally decrease the odds of out-of-home placement, net of other factors. There is no significant difference for those children ex- periencing emotional abuse compared to neglect. Counterintui- tively, those children with a sibling who has also been mal- treated are about 45% less likely to be removed from the home, net of all factors in the model. Open Access. 324  A. M. KAUFMAN The significant reduction in the odds of being removed from the home for those children who experience physical, sexual and multiple abuse types, illustrates that the child welfare sys- tem may not aim to remove children from an abusive home, but rather to remove children from homes in which there is a gen- eral inability to care. This may be due to the perception that abuse is an infrequent, rectifiable form of maltreatment, where- as neglect implies continuous and accumulating negative cir- cumstances that cannot be remedied through the provision of in-home services. This would also explain why there are no significant differences in the odds of out-of-home placement between those children who experience neglect and those who are emotionally abused. While emotional abuse encompasses a wide range of behaviors, bivariate analyses indicate that the most common form of emotional abuse experienced by children removed from the home is being abandoned for 24 hours or more. Therefore, emotional abuse, at least according to the Maltreatment Coding Scheme used for the present data collec- tion, is actually a very specific form of what is traditionally thought of as neglect, and thus also represents a more enduring form of maltreatment in comparison to sexual, physical and multiple abuse types. This possible explanation is also consis- tent with national data. For instance, in fiscal year 2007, of the 1760 children who died due to child abuse or neglect, 34.1 percent of child fatalities were attributed to neglect only, this percentage not including those children who suffered from multiple forms of maltreatment which also included neglect, and thus may far underestimate the true severity of maltreat- ment in regard to neglect (US Dept., 2009). Moreover, of the approximately 265,000 children who were removed from their homes during the same fiscal year, 69.2 percent were victims of neglect, whereas 8.6 percent suffered from physical abuse, 14.2 percent from multiple forms of maltreatment, and only 3.2 per- cent from sexual abuse (US Dept., 2009). A second possible explanation for the finding that sexual, physical and multiple maltreatment types reduce the odds of out-of-home placement in comparison to neglect is that perpe- trators of neglect are more likely to be the parents of child ne- glect victims. Therefore, out-of-home placement is the most reasonable solution for children who are neglected, as their offenders usually reside in the same household. For other types of maltreatment, though, parents may not be the perpetrators, and thus the child can be removed from the dangers of such abuse without being removed from the home. This second ex- planation is supported by 2007 National Child Abuse and Neg- lect Data System (NCANDS) data, where the percentage of perpetrators of sexual abuse was highest among friends or neighbors at 57.7 percent and child daycare providers at 23.9 percent, compared to only 2.4 percent of such perpetrators be- ing parents. For physical abuse, child daycare providers consti- tuted 14.1 percent of perpetrators, and friends and neighbors constituted another 14.4 percent, compared to only 9.7 percent whom were parents. For neglect cases, on the other hand, 66.1 percent of perpetrators were the parents of the victim (US Dept., 2009). However, the finding that having a sibling who has also been victimized in some form reduces the odds of out-of-home placement, net of all factors in the model, is still unclear. The inclusion of maltreatment specific variables reduces the racial disparity in out-of-home placement from black children having 2.822 to 2.404 higher odds of being removed from the home compared to white children from Model 4. Additionally, these measures reduce the effects of both parental substance abuse and parental mental illness to insignificance, indicating a possible mediation effect. For instance, parents experiencing substance abuse and mental health issues may unintentionally emotionally abuse or neglect their children as a result of such illnesses, and these two types of maltreatment are the forms most likely to result in out-of-home placements among mal- treated youth. Importantly, while the effect of race remains statistically significant in all models, about 28% of the racial disparity is explained from the first to the final model in the series of regressions. Ordered Placement by Race In the analyses that follow (not shown here due to limited significant findings), the full sample is partitioned by race to see what, if any, factors matter differently for white and black maltreated children in predicting the likelihood of out-of-home placement. Relevant risk and other factors are entered into the regression in the same order for the partitioned models as was the case for the full sample, and differences in coefficients be- tween the two models are compared using z-tests. It is also important to note that due to the small size of the black sample, there is a reduction in statistical power in the partitioned models, rendering it more difficult to find significant effects within the black model, as well as significant differences between the black and white models. For the model including only black children, AFDC and emotional abuse, in comparison to neglect, are the only variables which aid in the prediction of home re- moval. For the model including only white children, parental mental illness, prior child behavioral problems, sibling victimi- zation, and sexual abuse are the significant predictor variables. However, z-tests indicate that the only differences across race are for parental mental illness and emotional abuse as the mal- treatment type. For white children, parental mental illness in- creases the odds of being removed from the home by about 81 percent, while for black children there is no significant effect. Emotional abuse, on the other hand, increases the odds of out- of-home placement by a factor of 6.213 for black children, while there is no significant effect of emotional abuse among white children. While examining these effects separately may not provide much understanding in regard to racial disparity in CPS, two propositions can be made upon examining these effects simul- taneously, based on prior research in the juvenile justice and child maltreatment literatures. Going back to the bivariate re- sults in Table 1, there is no significant difference in the number of parents suffering from mental illness among white and black children. Additionally, parental mental illness and emotional abuse are significantly positively correlated. Yet parental men- tal illness is a significant predictor of out-of-home placement only for whites, while emotional abuse is significant only for blacks. One possible explanation can be understood through the work of Bridges and Steen (1998), where they find that while the offenses of minority youth are often seen as individual fail- ings in the form of negative attitudinal and personality traits, these same offenses are often portrayed as being a result of negative environmental factors for white adolescents. Extrapo- lating these findings to the arena of child maltreatment and adult offenders, then, allows for the hypothesis that among parents who maltreat their children, black parents will be seen as personally responsible for the abuse and neglect their child- Open Access 325  A. M. KAUFMAN ren suffer, while factors beyond the individuals’ control will be used to remove accountability from white parents. Thus, white parents victimize children as a result of mental illnesses, medi- cal conditions beyond their control which cause them to be neglectful, aggressive, impulsive, and so on. Black parents, on the other hand, despite having a diagnosed mental illness still choose to maltreat their children, according to this perspective. Whether this is because they have chosen not to seek treatment for their illness, or because it is believed the maltreatment would occur regardless of the presence of illness, black parents are seen as solely responsible for maltreatment. A second pos- sible explanation, related to the first, is the effect of socioeco- nomic status in the acceptance of a mentally ill label. Bivariate analyses indicate that there is a statistically significant differ- ence in approximate socioeconomic status between white and black maltreated children. Moreover, the partitioned models illustrate that while the percent of families receiving AFDC payments within the subject’s census tract is a significant pre- dictor in being removed from the home for black children, there is no significant effect for white children. As illustrated by Brown (2008), black children may be at an increased risk for out-of-home placement due to living in impoverished neigh- borhoods where access to the kinds of support and services needed to both prevent and rectify child maltreatment is limited. One of these suggested services is mental health and family counseling. Thus, even for black parents who are diagnosed as having a mental illness, having limited access to treatment and support services implies a lower likelihood of treatment seeking behaviors, and thus mental illness among blacks may be seen as less serious among both mental health and child welfare offi- cials. Finally, it is noteworthy that when the full model is par- titioned by race, the predictive efficacy for out-of-home place- ment in the black model is 14 percent, but only 9 percent in the white model. This finding illustrates that regardless of any ra- cial bias which may exist within the child welfare system, it appears different placement processes exist for black and white children when deciding whether to remove a maltreated child from the home. Study Limitations The sample used here is regional in nature, being limited to a large urban county in the Northwest United States. Although moderate in size, being comprised of 877 treatment cases, it is hard to generalize these findings beyond the Northwest United States to a national level without compromising their validity, reliability and statistical significance. Another possible issue with these data, as with any official data source, is the accuracy of the files. Many courthouse officials and social workers who document these child maltreatment cases may accidentally or intentionally misreport the incidents of the child maltreatment cases they are responsible for. Also problematic is the fact that only those cases which became dependents of the court are included in this study. Therefore, it is impossible to know if any racial disparity in out-of-home placements can be accounted for, either completely or partially, by a similarly large racial dispar- ity in reporting. Conclusion This study aimed to answer two questions: First, does a mal- treated child’s race affect their likelihood of receiving an out- of-home placement? Second, do different factors matter for black and white children within the decision making process? In reference to the first question, two competing explanations have been posited in previous literature. The first, black child- ren experience more serious forms of maltreatment and have fewer resources to remedy the maltreatment situation through informal means than do white children. The second, there is an underlying bias within the child welfare system, where dis- criminatory beliefs about the perceived threat and dangerous- ness of certain groups and their abilities to care for their chil- dren may contribute to black children being disproportionately removed from their homes. While this study finds evidence supportive of the first explanation, the results are also consis- tent with the possibility of an underlying racial bias within the sys te m. The inclusion of a variety of maltreatment, demo- graphic, familial and other risk factors accounted for approxi- mately 28% of the racial disparity in out-of-home placements. But, there remains a large amount disparity left to be explained. While there always exists the possibility that some variables with predictive power are not available in the data and are thus left unexamined, that black children continue to experience odds 2.404 times of white children in the full regression exam- ined here lends support to the possibility of an underlying racial bias within child welfare. In reference to the second question, findings illustrate that while few factors seem to matter differently for black and white children to a statistically significant degree, there are two dif- ferences that stand out. First is the differential effect of parental mental illness, which is a significant predictor of white but not black children being removed from the home. Second is the differential effect of emotional abuse, in comparison to neglect, which is a significant predictor of home removal for black child- ren, but not white children. These findings seem to support the conclusions made in previous research that black families may be held to different standards, as compared to white families. However, some caution may be necessary in the interpretation of these findings. This study was unable to account for factors such as parental awareness of the maltreatment of their children or their amenability toward resolving the situation, which may be key in determining aspects of parent’s mental and emotional state. Perhaps more important are those significant factors within the partitioned models than those significantly different across the models by race. For black children, the only predictive fac- tors for the variation in out-of-home placement are the per- centage of the population within the subject’s census tract re- ceiving AFDC payments and emotional abuse as the maltreat- ment type. For white children, parental mental illness, prior childhood behavioral problems, sibling victimization and sex- ual abuse matter to a statistically significant degree in deciding whether out-of-home placement is warranted. Furthermore, while the predictive efficacy for the model including only black children was 14 percent, this same model had a predictive effi- cacy of only 9 percent for white children. It appears for at least black children, then, the child welfare system operates less on the premise of removing a child from a home on the basis of maltreatment, or more specifically in reference to specific forms of abuse, than it does on the basis of what it sees as long-term neglect or an inability to care. Among white children, on the other hand, deleterious parental characteristics and abuse seem to play a bigger role in deciding whether or not a mal- treated child will be removed from the home. This is counter to the present study’s hypothesis that familial risk factors would Open Access. 326  A. M. KAUFMAN exert a stronger effect among blacks than whites. A possible explanation for these contradicting findings is that black fami- lies are often assumed to possess these deleterious characteris- tics, and thus, when such characteristics are actually confirmed in a maltreatment case, they add little weight to the placement decision. However, these characteristics, if viewed as less com- mon among whites, would illustrate a more problematic living situation, making out-of-home placement a more viable solu- tion. Even these characteristics, though, seem to predict only a small portion of variability in placements among white child- ren, leaving it somewhat unclear what factors are important for whites, or leading to the possible explanation that the decision to remove white children from the home is made on a much more individual-level basis than is the case for black families. In light of these findings, CPS should initiate programs for social workers to be sensitive to the specific issues that black families face, such as single-parenthood and lower socioeco- nomic status. It may also be in the best interest of these children for CPS to lobby for further funding to provide such things as mental counseling, drug abuse services, job placement, and child care. Black families would then not be separated because parents do not have the financial resources to provide for their children according to the specific standards set by CPS or other government officials. As much prior literature on out-of-home placement and childhood outcomes has shown, removing a child from the home can have long-term effects in many areas of their lives, such as the ability to form attachments with oth- ers, socioeconomic attainment, and risks for delinquency and criminality (Currie & Widom, 2010; DeGue & Widom, 2009; Ryan et al., 2008). Thus, whenever possible and in the best interest of the child, the goal for CPS should be to seek what- ever avenues necessary to keep a child with their family. Future research analyzing the racial disparity in out-of-home placements should examine to what extent these results can be generalized to the entire population of maltreated children. More qualitative and survey-oriented research may also be helpful in understanding exactly what processes are at play to make such factors as parental mental illness and parental sub- stance abuse operate differently among black and white mal- treated youth. This study was also not able to account for the possible existence of reporting differentials, which may result in a possible selection effect when analyzing just those cases which make it to the official processing stage. Finally, a num- ber of key variables which may further explain the racial-dis- parity in out-of-home placement, but which were not available in the present data, are family structure, a better measure of maltreatment severity beyond the separation of maltreatment types, and a more precise individual-level measure of socio- economic status. Thus, it is imperative for researchers in the child welfare arena to identify what additional factors contrib- ute to the placement decision among maltreated children, and if such characteristics can lead to a better understanding of the seemingly differential processes for blacks and whites within the child welfare system. REFERENCES Albonetti, C. A. (1991). An integration of theories to explain judicial discretion. Social Problems, 38, 247-266. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/800532 Barth, R. P. (2009). Preventing child abuse and neglect with parent training: Evidence and opportunities. Fut ur e o f Ch i l dr e n, 1 9, 95-118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/foc.0.0031 Barth, R. P., Wildfire, J., & Green, R. L. (2006). Placement into foster care and the interplay of urbanicity, child behavior problems and poverty. America n Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 7, 358-366. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.76.3.358 Billingsley, A., & Giovannoni, J. (1972). Children of the storm: Black children and American child welfare. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Jovanovich. Bridges, G. S., & Steen, S. (1998). Racial disparities in official assess- ments of juvenile offenders: Attributional stereotypes as mediating mechanisms. American Sociological Review, 63, 554-570. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2657267 Brown, K. (2008). African American children in foster care: HHS and congressional actions could help reduce proportion in care. Testi- mony before the Subcommittee on Income Security and Family Support, Committee on Ways and Means, House of Representatives. United States Government Accountability Office. Burns, B. J., Phillips, S. D., Wagner, H. R., Barth, R. P., Kolko, D. J., Campbell, Y., & Landsverk, J. (2004). Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare: A national survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Ado- lescent Psychiatry, 43, 960-970. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000127590.95585.65 Courtney, M. E., McMurtry, S. L., & Zinn, A. (2004). Housing prob- lems experienced by recipients of child welfare services. Child Wel- fare, 83, 393-422. Currie, J., & Widom, C. S. (2010). Long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect on adult economic well being. Child Maltreatment, 15, 111-120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077559509355316 DeGue, S., & Widom, C. S. (2009). Does out-of-home placement me- diate the relationship between child maltreatment and adult criminal- ity? Child Maltreatment, 14, 344-355. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077559509332264 Drake, B., Lee, S. M., & Jonson-Reid, M. (2009). Race and child mal- treatment reporting: Are blacks overrepresented? Children & Youth Services Review, 31, 309-316. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.08.004 Hampton, R. L., & Newberger, E. H. (1985). Child abuse incidence and reporting by hospitals: Significance of severity, class and race. Amer- ican Journal of Public H ealth, 75, 56-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.75.1.56 Hill, G. D., Harris, A. R., & Miller, J. L. (1985). The etiology of bias: Social heuristics and rational decision making in deviance processing. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 22, 135-162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022427885022002003 Hill, R. B. (2004). Institutional racism in child welfare. Race and Soci- ety, 7, 17-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.racsoc.2004.11.004 Kirk, R. S., & Griffith, D. P. (2008). Impact of intensive family presser- vation services on disproportionality of out-of-home placement of children of color in one state’s child welfare system. Child Welfare League of America, 87, 87-105. Knott, T., & Donovan, K. (2010). Disproportionate representation of African-American children in foster care: Secondary analysis of the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System, 2005. Children & Youth Services Review, 32, 679-684. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.01.003 Lane, W. G., Rubin, D. M., Monteith, R., & Christian, C. W. (2002). Racial differences in the evaluation of pediatric fractures for physical abuse. Journal of the American Medical Association, 288, 1603- 1609. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.13.1603 Lindsey, D. (1994). Factors affecting the foster care placement decision: An analysis of national survey data. American Journal of Orthopsy- chiatry, 6, 272-281. Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Sutton, P. D., Ventura, S. J., Menacker, F., Kirmeyer, S., & Mathews, M. S. (2009). Births: Final data for 2006. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. Miller, O. A., & Gaston, R. J. (2003). A model of culture-centered child welfare practice. Child Welfare, 82, 235-249. National Poverty Center, The University of Michigan (2007). Poverty in the United States. http://npc.umich.edu/poverty/ Open Access 327  A. M. KAUFMAN Open Access. 328 Needell, B., Shaw, T., Magruder, J., & Putnam-Hornstein, E. (2007). Racial disproportionality and disparity in child welfare: The dispar- ity index. The National Child Welfare Data and Technology Confer- ence, Washington, 18-19 July 2007. Osterling, K. L., D’Andrade, A., & Austin, M. J. (2008). Understanding and addressing racial/ethnic disproportionality in the front end of the child welfare system. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 5, 9-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J394v05n01_02 Phillips, S. D., Burns, B. J., Wagner, H. R., & Barth, R. P. (2004). Parental arrest and children involved with child welfare service agen- cies. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 74, 174-186. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.74.2.174 Pinderhughes, E. E. (1991). The delivery of child welfare services to African American clients. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 61, 599-605. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0079293 Polansky, N. A., Chalmers, M. A., Buttenweiser, E., & Williams, D. P. (1981). Damaged parents: An anatomy of child neglect. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Rawal, P., Romansky, J., Jenuwine, M., & Lyons, J. S. (2004). Racial differences in the mental health needs and service utilization of youth in the juvenile justice system. The Journal of Behavioral Health Ser- vices & Research, 31, 242-254. Rivaux, S. L., James, J., Wittenstrom, K., Baumann, D., Sheets, J., Henry, J., & Jeffries, V. (2008). The intersection of race, poverty and risk: Understanding the decision to provide services to clients and to remove children. Child Welfare League of America, 87, 151-168. Ryan, J. P., Testa, M. F., & Zhai, F. (2008). African American males in foster care and the risk of delinquency: The value of social bonds and permanence. Child Welfare League of America, 87, 115-140. Sampson, R. J. (1986). Effects of socioeconomic context on official re- action to juvenile delinquency. American Sociological Review, 51, 876-885. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2095373 Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. (1993). Structural variations in juvenile court processing: Inequality, the underclass, and social control. Law and Society Review, 27, 285-311. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3053938 Schuck, A. M. (2005). Explaining the black-white disparity in mal- treatment: Poverty, female-headed families, and urbanization. Jour- nal of Marriage and Family, 67, 543-551. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00152.x Sedlack, A. J., & Broadhurt, D. D. (1996). Third National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Center of Child Abuse and Neglect. Tonry, M. H. (1995). Malign neglect: Race, crime, and punishment in America. New York: Oxford University Press. US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth and Families (2009). Child Maltreatment 2007. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. Widom, C. S., & Maxfield, M. G. (2001). An update on the “cycle of violence”. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice Office of Jus- tice Programs, National Institute of Justice. Wulczyn, F. (2009). Epidemiological perspectives on maltreatment pre- vention. The Future o f Children, 19, 39-66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/foc.0.0029

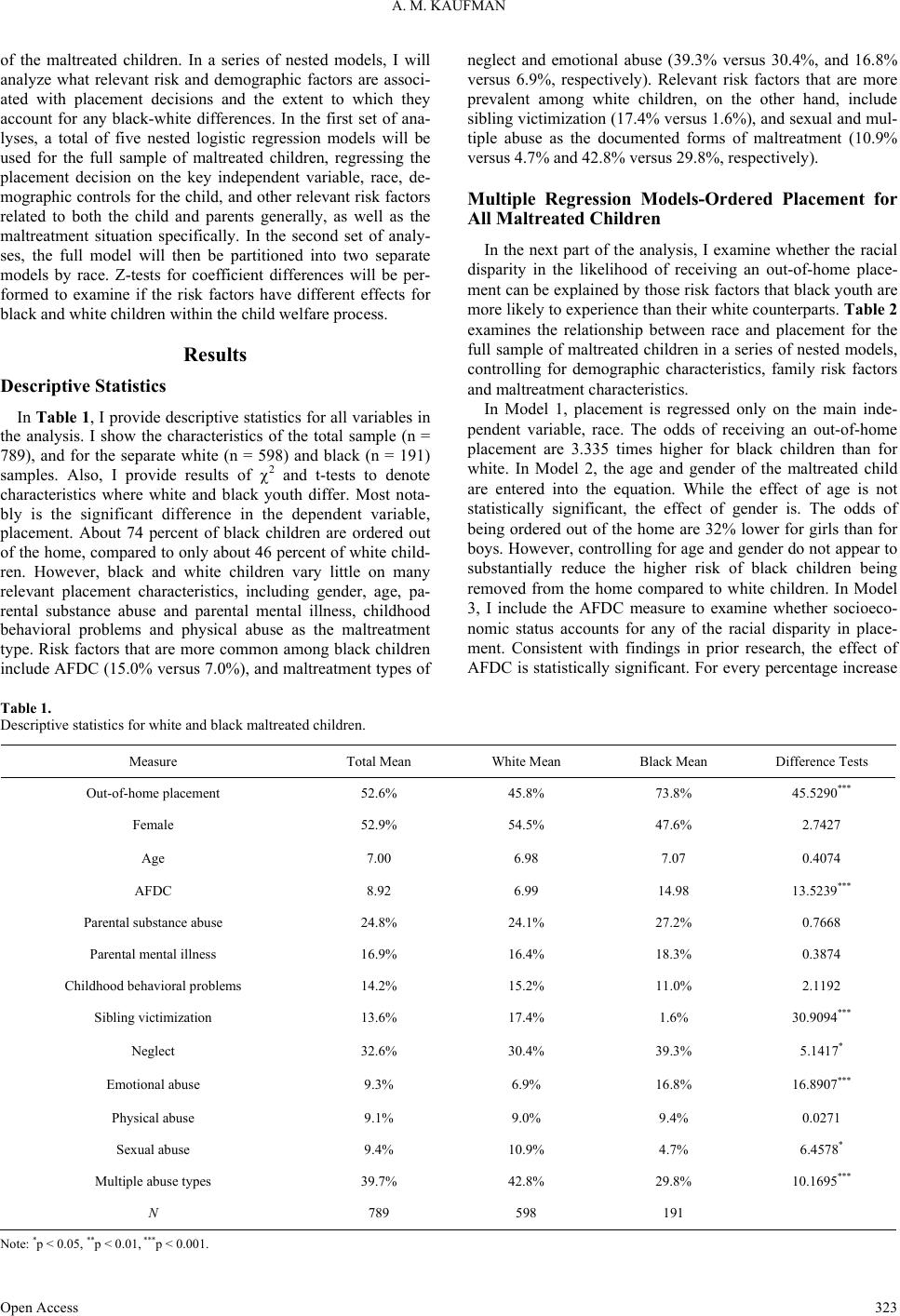

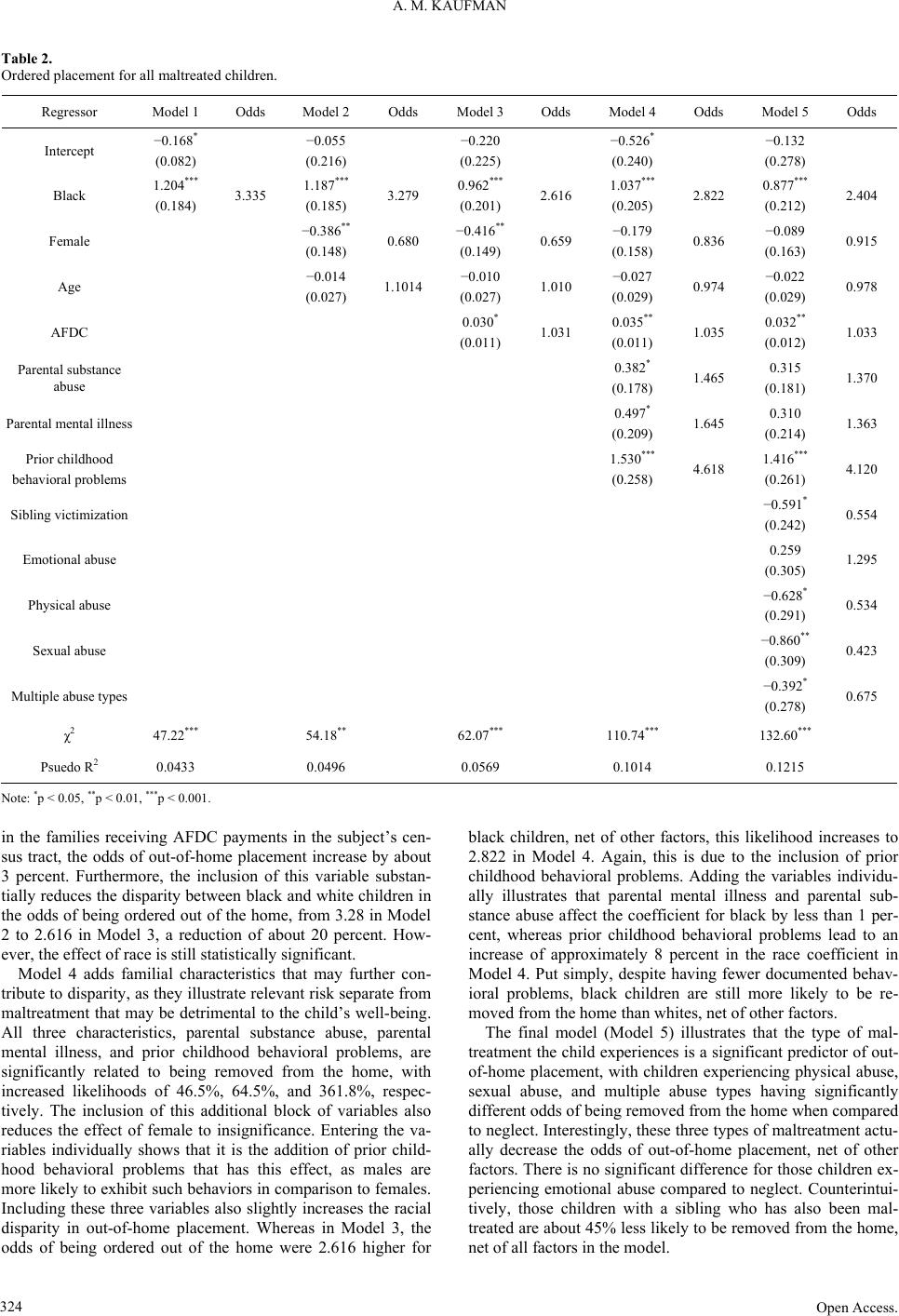

|