Vol.5, No.12A, 86-96 (2013) Health http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/health.2013.512A012 Personality factors and self-perceived health in Chilean elderly population Pedro Olivares-Tirado*, Gonzalo Leyton, Eduardo Salazar Studies and Development Department, Superintendence of Health, Santiago, Chile; *Corresponding Author: polivares@superdesalud.gob.cl Received 15 October 2013; revised 16 November 2013; accepted 25 November 2013 Copyright © 2013 Pedro Olivares-Tirado et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Empirical evidence suggests that the stability of personality itself contributes to successful age- ing and is associated with longer life. The aim of this study was to investigate the association be- tween personality traits and the self-perceived health status, stratified by medical conditions in a representative sample of non-institutionalized elderly people in Chile. The data used for this study come from the fourth waves (2009) of the Chilean Social Protection Survey (SPS-2009). In- cluded were a total of 2655 subjec ts aged 65 and over. The results showed that higher scores of all five personality factors were associated with good health. Those with the perception of poor health were more likely to be female, with lower education level and older than those with good health. With the exception of agreeablen ess, strong and significant associations with self-perceived health were demonstrated for extraversion, con- scientiousness, emotional stability and open- ness, among elderly with medical conditions. Among elderly without medical problems, sig- nificant associations with self-perceived health were demonstrated only for extraversion, agree- ableness and emotional stability. This study has shown that there is a consistent association between personality factors and self-perceived health throughout the older population. Our re- sults suggest that extraversion and openness traits could be acting as “protector” factors and agreeableness and conscientiousness traits as “resilient” factors, facing to the health problems among elderly people. Keywords: Serous Personality; Self-Perceived Health; Ageing; TIPI Questionnaire 1. INTRODUCTION Along with most other nations, Chile is undergoing an accelerated growth of older populations with the in- creased life expectancies. By 2025, the proportion of people aged 65 and over is expected to reach 14% of the total population and more than one million will be per- sons aged 75 or more in Chile [1]. With the moderniza- tion of the society and socioeconomic development in the last 3 decades, the cultural values and the family structure have been modified. Furthermore, values, be- liefs and preferences of the elderly themselves have been changing, and the current older generations tend to have a stronger desire for autonomy and independence. Thus, in this changing society, it is important to examine life conditions of older people to better understand their ad- aptation to the aging process and consequences on their health and wellbeing. Interest in the association between personality charac- teristics and health has been renewed in recent years. Studies have shown a strong association between per- sonality characteristics and health suggesting that per- sonality traits could contribute to self-perceived health, health outcomes and longevity [2,3]. It has also been shown that self-perception of health has shown its sig- nificant ability to predict a variety of outcomes, includ- ing service utilization, emotional distress, morbidity and mortality [4-6]. Increased empirical evidence shows that personality in terms of enduring dispositions remains stable after ap- proximately age 30, exerting fairly generalized effects on human behavior and constituting an important determi- nant of psychological well-being in old age [7-9]. It is suggested that the stability of personality itself contrib- utes to successful ageing by allowing the individual to plan the future [10], enhance their health-related quality of life, prevent the disease progression [11] and even is associated with longer life [3]. Personality constructs deserve special consideration Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  P. Olivares-Tirado et al. / Health 5 (2013) 86-96 87 when attempting to predict individual differences in be- haviors. One of the current, predominant frameworks of the personality is the five-factor model (FFM). The FFM is a comprehensive, empirical, data-driven research find- ing [12]. The five-factor model has emerged as an im- portant taxonomy of global personality traits and appears to hold a great promise for investigations of correlation between the personality and various behaviors because of its robustness and parsimony [13-15]. The five-factor model of personality is a hierarchical organization of personality traits in terms of five broad bipolar domains or dimensions that are defined by clus- ters of interrelated specific traits: extraversion, agree- ableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience. These five overarching domains have been found to contain and subsume most known personality traits and are assumed to represent the basic structure behind all personality traits. Extraversion describes de- grees of interpersonal interactions. Agreeableness esti- mates the quality of interpersonal orientation. Conscien- tiousness estimates motivation in goal-directed behavior. Neuroticism measures degrees of emotional stability. And openness to experience estimates the willingness to accept novel ideas [16]. These five factors provide a rich conceptual frame- work for integrating all the research findings and theory in the personality psychology [17]. All five factors were shown to have convergent and discriminant validity acro- ss instruments and observers, and to endure across dec- ades in adults [13,14]. The most frequently used meas- ures of the five factors comprise either items that are self-descriptive sentences [18] or items that are single adjectives in the case of lexical measures [19]. A research using both self-descriptive sentences and lexical meas- ures supports the comprehensiveness of the FFM model and its applicability across observers and cultures [13]. The advantages and limitations of the five-factor mo- del of personality as an integrating framework for studies of personality and health had been widely discussed. Al- though the FFM model has some potential limitations, the application of this method—as well as other aspects of current personality theory and research—is likely to facilitate progress in the study of how personality influ- ences health. Personality attributes have been shown to mediate health-related behaviors and health outcomes [2,20-24]. On the other hand, self-perceived health (SPH) is one of the most commonly used psychometric indicators in health surveys. SPH has often been thought of as meas- uring only “subjective” health, the opposite to physi- cian-rated health, which is considered as an “objective” measurement. However, in several longitudinal studies, SPH has been found to be a good predictor for survival and for future health outcomes even better than a physi- cian’s assessment [25-32]. SPH is a reliable and valid measure for assessing the subjective and objective health of individuals and in a large-scale survey [5,25,33,34]. Since elderly people are prone to several health prob- lems which have physical, psychological and social com- ponents, self-perceived health is an important factor in old age. Self-perceived health has been extensively stud- ied in older populations. A range of important factors such as chronic diseases, mortality, health care utiliza- tion, long-term care utilization and health-related quality of life have been associated with self-perceived health in the elderly population [26-32,35-38]. Some authors have reported that old people perceive their health in positive terms and tend to over-estimate their health compared with objective health measure- ments [32,39-44]. Other data support the view that eld- erly people are more pessimistic in their perceptions of their own health than younger people, even after control- ling for objective health conditions [45,46]. It is possible that these differences are explained at least partly, by the individual personality traits. On the other hand, the association of some socio- demographic variables or medical conditions with SPH of the elderly people has varied in previous studies. Eld- erly men tend to report poorer health than elderly women for similar objective health conditions [40,42,47]. Poor education and low socio-economical status are associated with poor self-rated health [39,44,48]. The number of symptoms and medical conditions, depression, heart dis- ease, stroke decreased functional capacity and sensory problems all correlate positively with low self-rated health in elderly [26,39-44,47]. The purpose of this study was to investigate the asso- ciation between personality traits and the perceived health status in a representative sample of the older Chilean population. The evaluation of personality traits was based on the FFM model, and measured with the Questionnaire of Personality TIPI (Ten-Item Personality Inventory). The self-perceived health evaluation was based on the question of the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Room Conditions [49]: “How is your health in general?” To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the role of personality traits in explaining variations in self-perceived health in the elderly Chilean population. 2. METHODS 2.1. Data & Participants The data used for this study comes from the fourth (2009) waves of the Chilean Social Protection Survey (SPS). The SPS is a nationally and regionally representa- tive household survey that contains extensive individual information about participation in the labor market and Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  P. Olivares-Tirado et al. / Health 5 (2013) 86-96 88 in the social protection system, as well as socioeconomic characteristics. It also contains a detailed set of health and wealth questions, as well as questions that measure the financial knowledge of respondents and their level of risk aversion. The SPS contains longitudinal data for a sample of 20,000 individuals firstly interviewed in 2002, with follow-ups in 2004, 2006 and 2009 [50]. The fourth wave of the SPS was fielded between April and December of 2009. The overall response rate was 76.5% on a sample of 19,512 peoples. Thus, the fourth wave of the SPS-2009 contains longitudinal data for 14,463 individuals [50]. In the SPS elderly people were oversampling to enhance the likelihood to build a sample with sufficient representation of this age group. The study sample corresponds to 2655 subjects aged 65 and over. 2.2. Measures 2.2.1. Personality Traits The evaluation of personality traits was based on the FFM model, and measured with the Questionnaire of Personality TIPI (Ten-Item Personality Inventory) de- veloped by Gosling, Renfro & Swann [51]. The TIPI questionnaire is a validated short-form for use in applied research settings where questionnaire space and respon- dent time are limited [51]. TIPI is a standard 10-item measure of the Big-Five personality dimensions. Each item consists of two descriptors, separated by a comma, using the common stem, ‘‘I see myself as:’’. Two sepa- rate items together covered the breadth of each domain including the high (+) and low(−) poles. The resulting five dimension were: Extraversion [(+): extraverted, en- thusiastic/(−): reserved, quiet], Agreeableness [(+): sym- pathetic, warm/(-): critical, quarrelsome], Conscien- tiousness [(+): dependable, self-disciplined/(−): disorgan- ized, careless], Emotional stability [(+): calm, emotion- ally stable/(−): anxious, easily upset] and Openness to experience [(+): open to new experience, complex/(−): conventional, uncreative]. Each item is rated on a 7-point scale that ranges from 1 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly). To score TIPI scales, items 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 are reversed-scored (i.e., recode a 7 with 1, a 6 with 2, a 5 with 3, etc) and then, take the average of the two items (the standard item and the recoded reverse-scored item (R)) that make up each scale. Extraversion: item 1, 6R; Agreeableness: 2R, item 7; Conscientiousness: item 3,8R; Emotional stability: 4R, item 9 and Openness to experi- ence: item 5,10R (51). This variable was included as a continuous variable with one decimal. 2.2.2. Self-Perception of Health Self-perception of health status was assessed with a Likert-scale item question based on EU-SILC question on self-perceived health (“How is your health in gen- eral?”), which contains six answering categories; 1) ex- cellent; 2) very good; 3) good; 4) fair; 5) poor and 6) very poor. The European Union Statistics on Income and Liv- ing Conditions (EU-SILC, 2003) question on selfper- ceived health is part of the Minimum European Health Module (MEHM), which is also included in the Euro- pean Health Interview Survey (EHIS). Self-perceived general health (based on EU-SILC data) is one of the indicators of the health and long term care developed under the Open Method of Coordination (OMC) [49]. This variable was aggregated into two categories: good health (i.e., excellent, very good and good) and poor health (i.e., poor and very poor). Given that “fair” con- cept, is generally evasive and ambiguous in Chilean idiosyncrasy, fair category was excluded of the analysis. 2.2.3. Medical Conditions It is clear that physical illness and mental disorders in- fluence self-perception of health. One of the health questions (f38) in the SPS-2009, contribute to the evaluation of health problems and con- sequently with the burden of diseases at the population level. Individuals were asked to report whether they had specific diseases diagnosed by a physician, in the list on a yes/no format. The list of diseases includes eleven chronic diseases and conditions commonly found among older populations i.e.; respiratory problems, depression, diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiac problems, cancer, arthritis/arthrosis, kidney/urinary problems, stroke and mental disorders. With the exception of HIV/AIDS, the total number from the list was used for the analysis. 2.2.4. Socio-Demographics Features With the purpose to adjust for potential confounders, variables as; age, gender, educational level and marital status were included in the analysis. Age (years) was included as a continuous variable, gender as a dichoto- mous variable (0 = male, 1 = female), educational level as a categorical variable with 3 levels; primary (include- ing illiterates), high school and university level (include ing post-degree) and marital status as a categorical vari- able with 4 levels: single, married, divorced and wid- owed. 2.2.5. Statistical Analysis One-way ANOVAs were used to compare each dimen- sion of the personality between those with good and poor self-perceived health. The Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test was utilized to study the lineal associations between prevalence of self-reported health problems and self- perceived health status. A binary logistic regression was used to examine the association between personality traits and prevalence of self-reported health problems. Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA), with the Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  P. Olivares-Tirado et al. / Health 5 (2013) 86-96 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 89 Wilks-Lambda statistics, was used to study personality factors between those with self-perceived health good and poor health in both strata; with and without medical conditions. All the 5 personality dimensions were ana- lyzed simultaneously. Age, gender, education and marital status were incorporated as covariates. The results were presented as adjusted means and standard errors (S.E.) evaluated at the mean for the covariates in the total sam- ple. All analyses were conducted using the SAS software, version 9.1 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc.). 3. RESULTS 3.1. Descriptive Statistics Table 1 shows socio-demographic, health and person- ality characteristics for the whole sample. From the 2655 participants, 36% (961 cases) had good health. About 43% (1147cases) and 21% (547 cases) of the sample had either fair health or poor health, respectively. Mean age for the whole sample was 74 years. Fifty- one percent of the whole sample was females and 10.6% illiterates. Among those with good health; 44% were females, the mean age was 73 years, 8.7% had superior education level and 54.3% were married. The corre- sponding figures for those with poor health were; 60%, 75 years, 1.6% and 54.2%, respectively. As shown in Table 1, the prevalence of medical prob- lems increased with the decline in level of the selfper- ceived health among all conditions queried. With the ex- ception of high blood pressure, differences between good and poor health groups were highly significant (p < 0.0001). Table 1, also depicts means and standard devia- tions of all TIPI domain scores. For the whole sample, people who reported a good health had better scores in all TIPI personality dimensions than those reported a poor health. Table 1. Descriptive socio-demographic, medical condition and personality traits by self-perceived health (n: 2655). self-perceived health Poor/very poor (n: 547) Fair (n:1,147) Excellent/very good/good (n:961) Age (mean, std) 75 (7.46) 74 (7.05) 73 (6.60) Gender (% female) 60% 53% 44% Educational level (%) Primary 77.9% 75.0% 57.6% High school 18.5% 22.0% 33.7% Superior 1.6% 3.0% 8.7% Marital status (%) Single 10.5% 11.3% 11.6% Married 54.2% 55.2% 54.3% Divorced 5.5% 5.0% 7.6% Widowed 29.8% 28.5% 26.5% Medical conditions (% with condition) Respiratory problems 17.4% 9.0% 2.9% Depression 20.8% 10.5% 3.3% Diabetes mellitus 30.0% 20.3% 10.1% High blood pressure 68.2% 60.5% 39.9% Cardiac problems 27.6% 17.6% 5.3% Cancer 7.3% 2.7% 2.1% Arthritis/arthrosis 36.2% 21.7% 10.4% Kidney/urinary diseases 10.2% 3.6% 1.6% Stroke 2.7% 0.4% 0.2% Mental disorders 3.3% 0.9% 0.4% Personality scale(TIPI) (mean, std) Extraversion 3.7 (1.52) 3.8 (1.46) 4.2 (1.45) Agreeableness 5.1 (1.37) 5.3 (1.31) 5.2 (1.34) Conscientiousness 5.4 (1.33) 5.6 (1.32) 5.7 (1.31) Emotional stability 4.8 (1.41) 5.1 (1.35) 5.1 (1.36) Openness 3.9 (1.39) 4.1 (1.44) 4.3 (1.52)  P. Olivares-Tirado et al. / Health 5 (2013) 86-96 90 3.2. Personality Factors and So Cio-Demographics Characteristics For the whole sample, women had higher mean scores of extraversion, agreeableness and openness than the men. In turn, men had higher means scores of conscien tiousness and emotional stability than women. With ex- ception of openness (p = 0.05), there were no significant differences in mean personality trait scores between women and men (not shown). For the whole sample, an increasing association level was observed between the gradient of education levels - lower to higher education- and extraversion (p = 0.02), conscientiousness (p = 0.104) and openness (p = 0.002). There were no significant differences in mean scores of agreeableness and emotional stability among education levels (not shown). For the whole sample, there were no significant asso- ciation between personality trait scores and marital status. However, single individuals shown higher mean scores of conscientiousness (mean: 5.6), emotional stability (mean: 4.9), and openness (mean: 4.5). Married subjects shown higher mean scores of extraversion (mean: 4.2) and good scores of conscientiousness (mean: 5.5), agree- ableness (mean: 5.1), emotional stability (mean: 4.9) and openness (mean: 4.9).Widowed individuals shown simi- lar pattern than single individuals, excepting agreeable- ness (mean: 5.2) where they were the best scored. Di- vorced individuals showed the worse personality traits scores (not shown). 3.3. Personality Factors and Medical Conditions (Morbidity) For the whole sample, there were no significant dif- ferences in mean scores of extraversion, conscientious- ness, emotional stability and openness between subjects with and without medical conditions. However, those with medical conditions showed agreeableness mean score significantly better than individuals without medi- cal conditions (5.16 vs 5.02, p = 0.02). After adjustment for socio-demographic factors the association between agreeableness and reported medical conditions remained significant (OR: 1.081, 95% CI: 1.004-1.165) (not shown). Separate analysis for medical conditions and after ad- justing for socio-demographic factors, there were no sig- nificant associations between personality traits and respi- ratory problems, high blood pressure, cardiac problems, cancer, arthritis/arthrosis and kidney/urinary illness (Ta- ble 2). The level of extraversion and emotional stability (neuroticism) among those with depression was signifi- cantly lowers, compared to those without depression. On the other hand, a lower score of agreeableness was sig- nificant associated with diabetes compared with those without this medical condition. The level of conscien- tiousness among those with mental disorder was signifi- cantly lower, compared to those without mental disorders. Finally, the level of openness among those with stroke was significantly lower, compared to those without stroke (Table 2). 3.4. Personality Factors, Medical Conditions and Self-Perceived Health The results of the ANOVA shows relationships be- tween each of the individual items of the personality in- ventory and self-perceived health in both strata; with and without medical conditions are presented in Table 3. Without adjustment for socio-demographics factors, and with the exception of agreeableness all of the other per- sonality dimensions were significantly associated with self-perceived health in those who reported medical con- ditions. On the other hand, in those without medical con- ditions just extraversion and emotional stability were significantly associated with self-perceived health. Among those with and without medical conditions, comparing individual self-perception of health, those with perception of poor health were more likely to be female. Mean age of individuals with perception of poor health was higher than among those with good health. Higher education level was significantly associated with good health. The results of the MANOVAs are exhibited in Table 4. The overall MANOVAs were highly significant both among those with and without medical conditions. After adjustments for socio-demographic factors, all personal- ity traits except for agreeableness, were significantly associated with self-perceived health among those with medical conditions. Among those without medical condi- tions, and after adjustments; extraversion, agreeableness and emotional stability were significantly associated with self-perceived health. Of interest, three personality traits—conscientiousness, emotional stability and openness—that were significant among those with medical conditions and good self- perceived health, showed higher mean scores than those with perception of good self-perceived health among tho- se without medical conditions. 4. DISCUSSION The present study focused on the comprehensive five- factor model of personality and self-perceived health among subjects with and without medical conditions, in a nationally representative sample of elderly people. To our knowledge, this is the first study in Chile to observe an association between personality traits and self-per- ception of health in a community-based elderly popula- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  P. Olivares-Tirado et al. / Health 5 (2013) 86-96 91 Table 2. Adjusted OR (95% CI) for personality traits among elderly with and without medical conditions (n: 1914). Extraversion Agreeableness Conscientiousness Emotional stability Openness Respiratory problems without 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 with 0.93 (0.836-1.028) 1.10 (0.964-1.246) 0.91 (0.806-1.024) 1.00 (0.889-1.131) 1.01 (0.904- 1.122) Depression without 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 with 0.87 (0.787-0.952)** 1.03 (0.918-1.162) 1.04 (0.929-1.172) 0.87 (0.777-0.967)** 1.00 (0.901-1.098) Diabetes without 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 with 1.01 (0.935-1.086) 0.92 (0.841-1.008)* 1.01 (0.919-1.099) 0.99 (0.907-1.077) 1.03 (0.957-1.117) High blood pressure without 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 with 0.96 (0.892-1.039) 0.98 (0.888-1.072) 1.00 (0.916-1.102) 0.99 (0.907-1.083) 0.99 (0.914-1.071) Cardiac problems without 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 with 0.98 (0.903-1.063) 0.93 (0.839-1.023) 0.96 (0.875-1.061) 1.00 (0.913-1.103) 0.98 (0.901-1.070) Cancer without 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 with 0.96 (0.826-1.117) 1.04 (0.865-1.252) 1.05 (0.871-1.260) 0.92 (0.776-1.093) 1.02 (0.870-1.185) Arthrosis/arthritis without 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 with 0.96 (0.890-1.032) 1.04 (0.946-1.140) 1.00 (0.915-1.098) 0.97 (0.892-1.059) 1.04 (0.958-1.119) Kidney/Urinary Problems without 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 with 0.91 (0.790-1.049) 0.89 (0.753-1.051) 0.99 (0.840-1.166) 1.01 (0.855-1.181) 1.05 (0.905-1.214) Stroke without 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 with 1.10 (0.787-1.542) 0.85 (0.576-1.246) 1.02 (0.706-1.486) 0.77 (0.538-1.110) 0.66 (0.457-0.963)** Mental Disorders without 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 with 0.87 (0.644-1.163) 0.79 (0.573-1.100) 0.73 (0.541-0.976)** 0.79 (0.580-1.085) 0.89 (0.642-1.228) Adjustment for age, gender and education level. **p < 0.05;*p < 0.1. Table 3. Personality scores among elderly with and without medical conditions associated to self-perceived health. With Medical conditions Without Medical conditions Self-perceived health Self-perceived health Good (n:496) Poor (n:503) p-value Good (n:465) Poor (n:44) p-value Age (years, SD) 73 (6.38) 75 (7.29) 0.0001 72 (6.78) 78 (9.02) <0.0001 Gender(% female) 51.4% 61.2% 0.002 35.3% 54.6% 0.01 Education level (%) <0.0001 0.001 Primary 57.4% 78.8% 57.9% 87.5% High school 32.7% 19.6% 34.9% 10.0% Superior 9.9% 1.6% 7.2% 2.5% Marital status (%) NS NS Single 11.6% 9.6% 11.7% 20.5% Married 52.4% 54.6% 56.1% 50.0% Divorced 7.1% 5.8% 8.2% 2.3% Widowed 28.9% 30.0% 24.0% 27.2% TIPI Scales( una djusted mean, SD) Extraversion 4.23 (1.446) 3.76 (1.515) <0.0001 4.17 (1.465) 3.49 (1.522) 0.008 Agreeableness 5.24 (1.319) 5.14 (1.360) NS 5.23 (1.359) 4.93 (1.531) NS Conscientiousness 5.75 (1.260) 5.43 (1.341) 0.0001 5.59 (1.362) 5.21 (1.244) NS Emotional stability 5.19 (1.376) 4.78 (1.418) <0.0001 5.10 (1.335) 4.51 (1.216) 0.01 Openness 4.34 (1.508) 3.84 (1.390) <0.0001 4.25 (1.528) 3.98 (1.462) NS NS: no significant. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  P. Olivares-Tirado et al. / Health 5 (2013) 86-96 92 Table 4. Adjusted Personality scores among elderly with and without medical conditions associated to self-perceived health (MANO- VA Analysis). With Medical conditions Without Medical conditions Self-perceived health self-perceived health Good (n:496) Poor (n:503)p-value Good (n:465) Poor (n:44) p-value Extraversion 4.29 (0.094) 3.87 (0.110) <0.0001 4.31 (0.116) 3.72 (0.296) 0.0380 Agreeableness 5.15 (0.085) 5.02 (0.100) NS 5.21 (0.109) 4.67 (0.277) 0.0459 Conscientiousness 5.81 (0.081) 5.56 (0.096) 0.0049 5.73 (0.108) 5.43 (0.275) NS Emotional stability 5.08 (0.089) 4.64 (0.105) <0.0001 4.95 (0.106) 4.33 (0.270) 0.0191 Openness 4.50 (0.091) 4.13 (0.108) 0.0002 4.50 (0.116) 4.51 (0.296) NS Overall MANOVA: Wilks Lambda = 0.947, df = 5, den df = 896, F = 10.03 p = < 0.0001 Wilks Lambda = 0.975, df = 5, den df = 450, F = 2.30 p = 0.044 Adjusted for age, gender, educational level & marital status. tion. The major contribution of this study is its support for the notion that personality is associated with subjec- tive health in older people, independent of potential con- founding effects of the socio-demographic and medical conditions. As proposed by Contrada et al. (1999), the link be- ween personality and health may reflect three different though overlapping processes. First, personality traits are associated with factors that cause disease. Second, per- sonality may lead to behaviors that protect or diminish health. Last, personality traits are related to the success- ful implementation of health-related coping behaviors and adherence to treatment regimens [52]. Data from several studies indeed suggest that high scores in the extraver- sion and conscientiousness and low scores in neuroticism are among the best predictors of well-being, health and longer life in old age [3,24,53-55]. While the extraver- sion has been found to be linked to the positive health behavior, to good perceived health to longer life [3,56], neuroticism has been associated with more reports of psychological symptoms, poorer perceived health and a lower level of psychological well-being [57-59]. A large body of evidence suggest that conscientiousness was associated with positive health behaviors, health-pro- moting activities, adherence to medical regimens and the resilience face to adversity [21,25,60-66]. For the whole sample, after adjustment for socio- demographic factors, our results indicate that mean scores of agreeableness, conscientiousness and emotional stability among those with medical problems were higher than among those without medical conditions. However, the mean difference was significant for agreeableness and marginally significant (p = 0.08) for conscientious- ness. On the other hand, mean scores of extraversion and openness were higher among elderly without medical conditions. These differences were significant. Thus, our results suggest that extraversion and openness traits could be acting as “protector” factors and agreeableness and conscientiousness traits as “resilient” factors, face to the health problems among elderly people. After stratifying for medical conditions and control- ling for socio-demographic variables, our results indicate that personality traits show relevant associations with self-perception of health. In both strata with and without medical conditions, higher levels of all five personality factors were associated with good health. Strong and significant associations with self-perception of health were demonstrated for extraversion, conscientiousness, emotional stability and openness, among elderly people with medical conditions. No association was found be- tween agreeableness and perception of health among those with medical problems. On the other hand, among elderly people without medical problems, significant associations with self-perception of health were demon- strated for extraversion, agreeableness and emotional stability. No association was found between conscien- tiousness, openness and perception of health among those without medical problems. Our results are consis- tent with findings by Godwyn & Engstrom (2002) that personality factors show strong and significant associa- tions with self-perception of health, independent of physical and mental health problems. In the present study, independent of individual medical conditions there was a significant positive association between extraversion and self-perceived health in both bivariate and multivariate analysis. In other words, indi- viduals with higher scores of extraversion were likely to perceive their own health better. This finding is consis- tent with prior studies on older people that suggest that high scores in extraversion are among the best predictors of well-being and health in old age [24,54-56]. Moreover, individuals who score high on extraversion are prone to the physical active lifestyle [67]. Extraversion factor is considered as a protector factor of mortality [6] and as- sociated with decreased level of impairment among eld- erly people with the physical illness [21]. A positive association between conscientiousness and good perceived health was demonstrated among elderly people with medical problems. Our findings are in line with recent research from Goodwin et al. (2006), sug- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  P. Olivares-Tirado et al. / Health 5 (2013) 86-96 93 gesting consistent linkages between conscientiousness and improved health outcomes and functional health status among adults with physical illnesses, compared with those lower on conscientiousness. Conscientious- ness is often considered to have exclusive beneficial ef- fects on health outcomes [68]. A possible explanation for this association is that conscientious people may also be more able to cope with stressful life events, be more likely to monitor their health, high adherence to the pre- scribed medication [66] or more likely to maintain stable marriages and other social support networks which relate to their health [69]. The association between neuroticism and self-percep- tion of health was highly significant among those with medical problems and slightly attenuated among those elderly without medical problems. In other words, indi- viduals with lower scores of emotional stability were likely to perceive their self-perceived health worse. These findings are not surprising, given the well docu- mented association between neuroticism/negative affec- tivity and self-perception of poor health in clinical sam- ples [20,70] and as a strong predictor of psychological well-being in old age [52,71-73]. Our findings also pro- vide support for the suggestion from Goodwyn & Eng- strom (2002) that neuroticism increases the likelihood of perceived poor health even in the absence of medical problems. Openness has been related to the cognitive ability [74] which is well known as a predictor of longevity inde- pendent of a person’s social position [75] and a protector factor of premature mortality in adults over 55-year-old [69]. However, some studies question the over-rated role of openness and extraversion (emotional reactivity) as long-term predictors for adaptation and health in old age [9,55]. Our results show that the association between openness and self-perception of health among those eld- erly with medical problems was highly significant. It is likely that this relationship may be explained by the cog- nitive ability which may be acting as a relevant factor in the adaptation process at illness-resilience—in elderly people. This finding confirms results from Goodwyn (2002) that there is a striking association between open- ness and perception of health. The association observed between agreeableness and self-perception of health among those elderly without medical problems, was significant in the multivariate analysis. No association was found among those with medical problems. These data are inconsistent with find- ings by Goodwyn & Engstrom (2002) that there is no association between agreeableness and perception of health among adults without health problems. Also, Goodwyn & Friedman (2006) didn’t find the association between the agreeableness and the level of impairment among adults with physical illness. A possible explana- tion to this finding may be psychometrics difficulties to evaluate agreeableness dimension with only few de- scriptors [76]. Another explanation may be, given that agreeableness traits involve the quality of interpersonal orientation more than personal endurance. Those indi- viduals who are altruist, caring, sympathetic, warm or emotional supporter have a higher level of psychological well-being. Consequently, their perceived health is better when they are healthy than they are facing medical problems. This study has several limitations, which should be considered when interpreting results. First, the informa- tion on medical conditions was self-report. However, the majority of community-based studies that examine the relationship between self-perceived health and other out- comes use self-reported health problems [5]. Therefore, we believe this measure would provide a reasonable es- timate of medical disorders for the current study. Sec- ondly, self-perceived health construct (SPH item struc- ture) could be biased to an optimist pole, given that only two over 6 options have negative meanings. Thirdly, the number of medical and mental disorders queried is lim- ited and included as dichotomy responses. Then it is pos- sible that other disorders or severity of queried disorders may affect these relationships. However, the disorders that were asked about are consistent, in number and type, with those used in previous studies [5]. Lastly, a small sample of individuals with poor health in the strata with- out medical conditions is likely affecting some results in the statistical analysis of personality traits in this strata. 5. CONCLUSION In conclusion, the association between personality factors and self-perceived health is a consistent relation- ship throughout the older population. The analysis of personality traits could be used to guide the effort to raise the quality of public health interventions promoting the engagement of elderly people in behaviors that promote or protect health or functioning, to improve health out- comes and quality of life in old age. Future studies that investigate whether personality factors explain the rela- tionship between health problems and/or disability with self-perception of health or other health or well-being outcomes in elderly people are needed to improve our understanding of these associations. Further, other stud- ies that investigate gender differences and the overlap effects (interactions) of personality traits on self-perceived health must be necessary. REFERENCES [1] CHILE: Proyecciones y Estimaciones de Población. Total País: 1950-2050. Instituto Nacional de Estadística / Co- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  P. Olivares-Tirado et al. / Health 5 (2013) 86-96 94 misión Económica para América Latina y El Caribe (2005) División de Población. Centro Latinoamericano y Ca- ribeño de Demografía. Serie de la Publicación (CEPAL): OI No 208. http://www.ine.cl/canales/chile_estadistico/demografia_y _vitales/proyecciones/Informes/Microsoft%20Word%20- %20InforP_T.pdf [2] Goodwin, R. and Engstrom, G. (2002) Personality and the perception of health in the general population. Psycho- logical Medicine, 32, 325-332. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291701005104 [3] Terracciano, A., Lockenhoff, C.E., Zonderman, A.B., Ferrucci, L. and Costa, Jr., P.T. (2008) Personality pre- dictors of longevity: Activity, emotional stability, and conscientiousness. Psychosomatic Medicine, 70, 621-627. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817b9371 [4] Borawski, E.A., Kinney, J.M. and Kahana, E. (1996) The meaning of older adults’ health appraisals: Congruence with health status and determinant of mortality. Journal of Gerontology: Social Science, 51B, S157-S170. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronb/51B.3.S157 [5] Idler, E.L. and Benyamini, Y. (1997) Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38, 21-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2955359 [6] Maier, H. and Smith, J. (1999) Psychological predictors of mortality in old age. Journal of Gerontology: Psycho- logical Sciences, 54B, P44-P54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronb/54B.1.P44 [7] Sanford, N. (1963) Personality: Its place in psychology. In: Koch, S., Ed., Psychology: A Study of a Science, Vol. 5, McGraw-Hill, New York, pp. 488-592. [8] Allport, G.W. (1966) Traits revisited. American Psycho- logist, 21, 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0023295 [9] Perrig-Chiello, P., Jaeggi, S., Buschkuehl, M., Stähelin, H. and Perrig, W. (2009) Personality and health in middle age as predictors for well-being and health in old age. European Journal of Ageing, 6, 27-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10433-008-0102-8 [10] Costa, P.T., Metter, E.J. and McCrae, R.R. (1994) Person- ality stability and its contribution to successful aging. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27, 41-59. [11] Sörensen, S., Duberstein, P.R., Chapman, B., Lyness, J.M. and Pinquart, M. (2008) How Are personality traits re- lated to preparation for future care needs in older adults? The Journal of Gerontology B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63, P328-P336. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronb/63.6.P328 [12] Digman, J.M. (1990) Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annual Review of Psychology, 41, 417-440. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.41.020190.002221 [13] McCrae, R.R. and Costa, Jr., P.T. (1987) Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 81-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81 [14] McCrae, R.R. and John, O.P. (1992) An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. Journal of Per- sonality, 60, 175-215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00970.x [15] John, O.P. (1990) The “Big Five” factor taxonomy: Di- mensions of personality in the natural language and in questionnaires. In: Pervin, L.A., Ed., Handbook of Per- sonality: Theory and Research, Guilford Press, New York, 1990, 66-100. [16] Costa, Jr., P.T. and McCrae, R.R. (1992) Revised NEO personality inventory (NEOPI-R) and NEO five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa. [17] O’Connor, B. (2002) A quantitative review of the com- prehensiveness of the five-factor model in relation to popular personality inventories. Assessment, 9, 188-203. [18] De Fruyt, F., McCrae, R.R., Szirmák, Z. and Nagy, J. (2004) The Five-Factor personality inventory as a meas- ure of the five-factor model: Belgian, American, and Hungarian comparisons with the NEO-PI-R. Assessment, 11, 207-215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1073191104265800 [19] Goldberg, L.R. (1992) “The development of markers for the Big-five factor structure. Psychological Assessment, 4, 26-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.26 [20] Smith, T.W. and Williams, P.G. (1992) Personality and health: Advantages and limitations of the five-factor model. Journal of Personality, 60, 395-425. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00978.x [21] Goodwin, R.D. and Friedman, H.S. (2006) Health status and the five-factor personality traits in a nationally re- presentative sample. Journal of Health Psychology, 11, 643-654. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359105306066610 [22] Hampson, S.E., Goldberg, L.R., Vogt, T.M. and Du- banoski, J.P. (2006) Forty years on: teachers’ assessments of children’s personality traits predict self-reported health behaviors and outcomes at midlife. Health Psychology, 25, 57-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.57 [23] Tucker, J.S., Friedman, H.S., Tomlinson-Keasey, C., Schwartz, J.E., Wingard, D.L., Criqui, M.H., et al. (1995) Childhood psychosocial predictors of adulthood smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25, 1884-1899. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1995.tb01822.x [24] Duberstein, P.R., Sörensen, S., Lyness, J.M., King, D.A., Conwell, Y., Seidlitz, L., et al. (2003) Personality is asso- ciated with perceived health and functional status in older primary care patients. Psychology and Aging, 18, 25-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.18.1.25 [25] Maddox, G.L. and Douglass, E.B. (1973) Self-assessment of health: A longitudinal study of elderly subjects. Jour- nal of Health and Social Behavior, 14, 87-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2136940 [26] Kaplan, G.A., Barell, V. and Lusky, A. (1988) Subjective state of health and survival in elderly adults. The Journals of Gerontology, 43, 114-120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronj/43.4.S114 [27] Kaplan, G.A. (1983) Camacho T. Perceived health and mortality: A nine-year follow-up of the human population laboratory cohort. American Journal of Epidemiology, Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  P. Olivares-Tirado et al. / Health 5 (2013) 86-96 95 117, 292-304. [28] Jagger, C. and Clarke, M. (1988) Mortality risks in the elderly: Five-year follow-up of a total population. Inter- national Journal of Epidemiology, 17, 111-114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ije/17.1.111 [29] Wolinsky, F.D. and Johnson, R.J. (1992) Perceived health status and mortality among older men and women. The Journals of Gerontology, 47, 304-312. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronj/47.6.S304 [30] Idler, E.L., Kasl, S.V. and Lemke, J.H. (1990) Self- evaluated health and mortality among the elderly in New Haven, Connecticut and Iowa and Washington counties, Iowa, 1982-1986. Journal of Epidemiology, 131, 91-103. [31] Mossey, J.M. and Shapiro, E. (1982) Self-rated health: A predictor of mortality among the elderly. American Jour- nal of Public Health, 72, 800-808. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.72.8.800 [32] Branch, L., Jette, A. and Evashwick, C. (1981) Toward understanding elders’ health service utilization. Journal of Adolescent Health, 7, 80-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01323227 [33] Krause, N.M. and Jay, G.M. (1994) What do global self- rated health items measure? Medica l Care, 32, 930-942. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199409000-00004 [34] Mechanic, D. and Hansell, S. (1987) Adolescent compe- tence, psychological well-being, and self-assessed physi- cal health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 28, 364-374. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2136790 [35] Johnson, R.J. and Wolinsky, F.D. (1993) The structure of health status among older adults: disease, disability, func- tional limitation, and perceived health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 34, 105-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2137238 [36] Cohen, M.A., Tell, E.J. and Wallack, S.S. (1986) Client- Related risk factors of nursing home entry among eld- erly adults. Journal of Gerontology, 41,785-792. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronj/41.6.785 [37] Shapiro, E. and Tate, R. (1988) Who is really at risk of institutionalization? Gerontologist, 28, 237-245. [38] Molarius, A. and Janson, S. (2002) Self-Rated health, chro- nic diseases, and symptoms among middle-aged and eld- erly men and women. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 55, 364-370. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00491-7 [39] Maddox, G.L. (1962) Some correlates of differences in selfassessment of health status among the elderly. Journal of Gerontology, 17, 180-185. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronj/17.2.180 [40] Ferraro, K. (1980) Self-Ratings of health among the old and old-old. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21, 377-383. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2136414 [41] Linn, B.S. and linn, M.W. (1980) Objective and self-as- sessed health in the old and very old. Social Science & Medicine, 14A, 311-315. [42] Fillenbaum, G.G. (1979) Social context and self-assess- ments of health among the elderly. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 20, 45-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2136478 [43] Linn, M.W., Hunter, K.I. and linn, B.S. (1980) Self-As- sessed health, impairment and disability in Anglo, Black and Cuban elderly. Medical Care, 18, 282-288. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198003000-00003 [44] Cockerham, W.C., Sharp, K. and Wilcox, J. (1983) Aging and perceived health status. Journal of Gerontology, 38, 349-355. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronj/38.3.349 [45] Goldstein, M.S., Siegel, J.M. and Boyer, R. (1984) Pre- dicting changes in perceived health status. American Jour- nal of Public Health, 74, 611-614. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.74.6.611 [46] Levkoff, S.E., Cleary, P.D. and Wetle, T. (1987) Differ- ences in the appraisal of health between aged and middle- aged adults. Journal of Gerontology, 42, 114-120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronj/42.1.114 [47] Mitrushina, M.N. and Satz, P. (1991) Correlates of self- rated health in the elderly. Aging, 3, 73-77. [48] McCoy, J.L. and Brown, D.L. (1978) Health status among low-income elderly persons: Rural-Urban differences. So- cial Security Bulletin, 41, 14-26. [49] European Union Statistics on Income and Living Condi- tions (EU-SILC) (2003) European Commission. Eurostat. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/microd ata/eu_silc [50] Documento Metodológico. Centro de Microdatos. De- partamento de Economía. Universidad de Chile (2012) La Encuesta de Protección Social 2002-2009. www.observatorioprevisional.cl [51] Gosling, S.D., Rentfrow, P.J. and Swann Jr., W.B. (2003). A very brief measure of the big five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 504-528. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1 [52] Ozer, D.J. and Benet-Martinez, V. (2006). “Personality and the prediction of consequential outcomes”. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 401-421. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.19012 7 [53] Contrada, R.J., Cather, C. and O’Leary, A. (1999) Per- sonality and health: Dispositions and processes in disease susceptibility and adaptation to illness. In: Pervin, L.A. and John, O.P., Ed., Handbook of Personality, Guilford, New York, 576-604. [54] Samuelsson, S.M., Alfredson, B.B., Hagberg, B., Samuels- son, G., Nordbeck, B., Brun, A., Gustafson, L. and Risberg, J. (1997) The Swedish Centenarian Study: A multidisci- plinary study of five consecutive cohorts at the age of 100. The International Journal of Aging and Human Develop- ment, 45, 223-253. http://dx.doi.org/10.2190/XKG9-YP7Y -QJTK-BGPG [55] Friedman, H.S. (2000) Long-Term relations of personal- ity and health: Dynamisms, mechanisms, tropisms. Jour- nal of Personality, 68, 1089-1107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00127 [56] Benyamini, Y., Idler, E.L., Leventhal, H. and Leventhal, E.A. (2000) Positive affect and function as influence on self-assessments of health: Expanding our view beyond illness and disability. Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 55, P107- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  P. Olivares-Tirado et al. / Health 5 (2013) 86-96 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 96 P116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronb/55.2.P107 [57] Jerram, K.L. and Coleman, P.G. (1999) The big five per- sonality traits and reporting of health problems and health behaviour in old age. British Journal of Health Psychol- ogy, 4, 181-192. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/135910799168560 [58] Woodruff-Borden, J., Brothers, A.J. and Lister, S.C. (2001) Self-Focused attention: Commonalities across psychopatho- logies and predictors. Behavioural and Cognitive Psycho- therapy, 29, 169-178. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1352465801002041 [59] Gilhooly, M., Hanlon, P., Cullen, B., Macdonald, S. and Whyte, B. (2007) Successful ageing in an area of depri- vation: A quantitative exploration of the role of personal- ity and beliefs in good health in old age. Public Health, 121, 814-821. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2007.03.003 [60] Booth-Kewley, S. and Vickers Jr., R.R. (1994) Associations between major domains of personality and health behave- ior. Journal of Personality, 62, 281-298. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00298.x [61] Vollrath, M. and Torgersen, S. (2002) Who takes health risks? A probe into eight personality types. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 1185-1197. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00080-0 [62] Martin, L.R., Friedman, H.S. and Schwartz, J.E. (2007) Personality and mortality risk across the life span: The importance of conscientiousness as a biopsychosocial at- tribute. Health Psychology, 26, 428-436. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.428 [63] Bogg, T. and Roberts, B.W. (2004) Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: A meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychological Bulle- tin, 130, 887-919. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.887 [64] Brickman, A.L., Yount, S.E., Blaney, N.T., Rothberg, S.T. and De-Nour, A.K. (1996) Personality traits and long-term health status: The influence of neuroticism and conscien- tiousness on renal deterioration in type-1 diabetes. Psycho- somatics, 37, 459-468. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(96)71534-7 [65] Christensen, A.J. and Smith, T.W. (1995) Personality and patient adherence: Correlates of the five-factor model in renal dialysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 18, 305- 312. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01857875 [66] Axelsson, M., Brink, E., Lundgren, J. and Lotvall, J. (2011) The influence of personality traits on reported adherence to medication in individuals with chronic disease: An epi- demiological study in West Sweden. PLoS ONE, 6, Arti- cle ID: e18241. [67] Hampson, S.E., Goldberg, L.R., Vogt, T.M. and Duba- noski, J.P. (2007) Mechanisms by which childhood per- sonality traits influence adult health status: Educational attainment and healthy behaviors. Health Psychology, 26, 121-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.121 [68] Kardum, I. and Hudek-Knezevic, J. (2012) Relationships between five-factor personality traits and specific health- related personality dimensions. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 12, 373-387. [69] Taylor, M.D.,Whiteman, M.C., Fowkes, G.R., Lee, A.J., Allerhand, M. and Deary, I.J. (2009) Five factor model personality traits and all-cause mortality in the Edinburgh artery study cohort. Psychosomat ic Medicine, 71, 631-641. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181a65298 [70] Smith, T. W. and Gallo, L. C. (2001). Personality traits as risk factors for physical illness. In: Baum, A., Revenson, T. A. and Singer, J. E., Eds., Handbook of Health Psy- chology, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, 139-157 [71] Schmutte, P.S. and Ryff, C.D. (1997) Personality and well-being: Reexamining methods and meanings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 549-559. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.3.549 [72] Andrews, G., Clark, M. and Luszcz, M. (2002) Successful aging in the Australian longitudinal study of aging: Ap- plying the MacArthur model cross-nationally. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 749-765. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00288 [73] McCrae, R.R. (2002) The maturation of personality psy- chology: Adult personality development and psycholo- gical well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 36, 307-317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00011-9 [74] Harris, J.A. (2004) Measured intelligence, achievement, openness to experience, and creativity. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 913-929. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00161-2 [75] Whalley, L.J. and Deary, I.J. (2001) Longitudinal cohort study of childhood IQ and survival up to age 76. British Medical Journal, 322, 819-822. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.322.7290.819 [76] Romero, E., Villar, P., Gomez-Fraguela, J.A. and Lopez- Romero, L. (2012) Measuring personality traits with ultra- short scales: A study of the Ten Item Personality Inven- tory (TIPI) in a Spanish sample. Personality and Individual Difference s, 53, 289-293. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.03.035

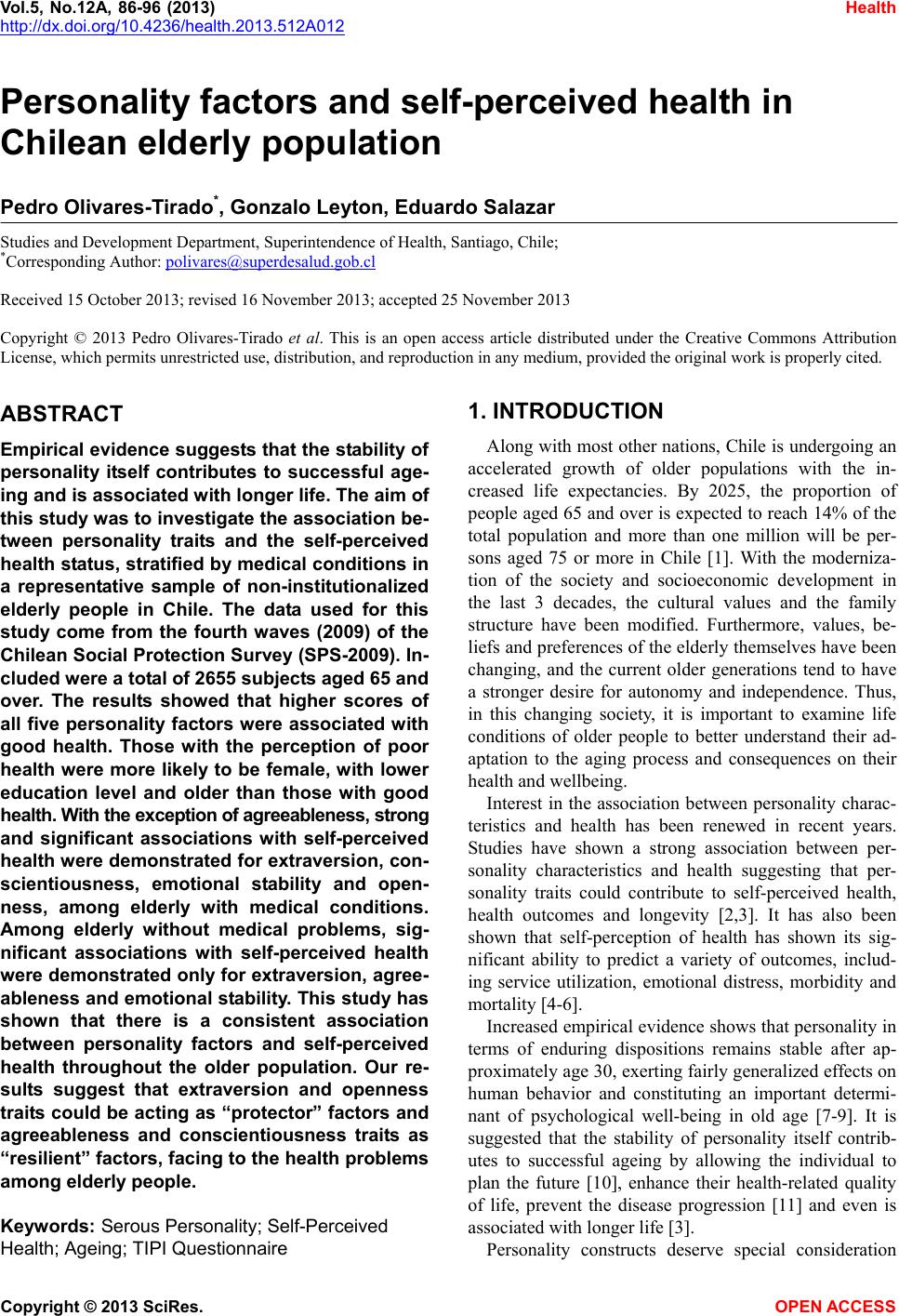

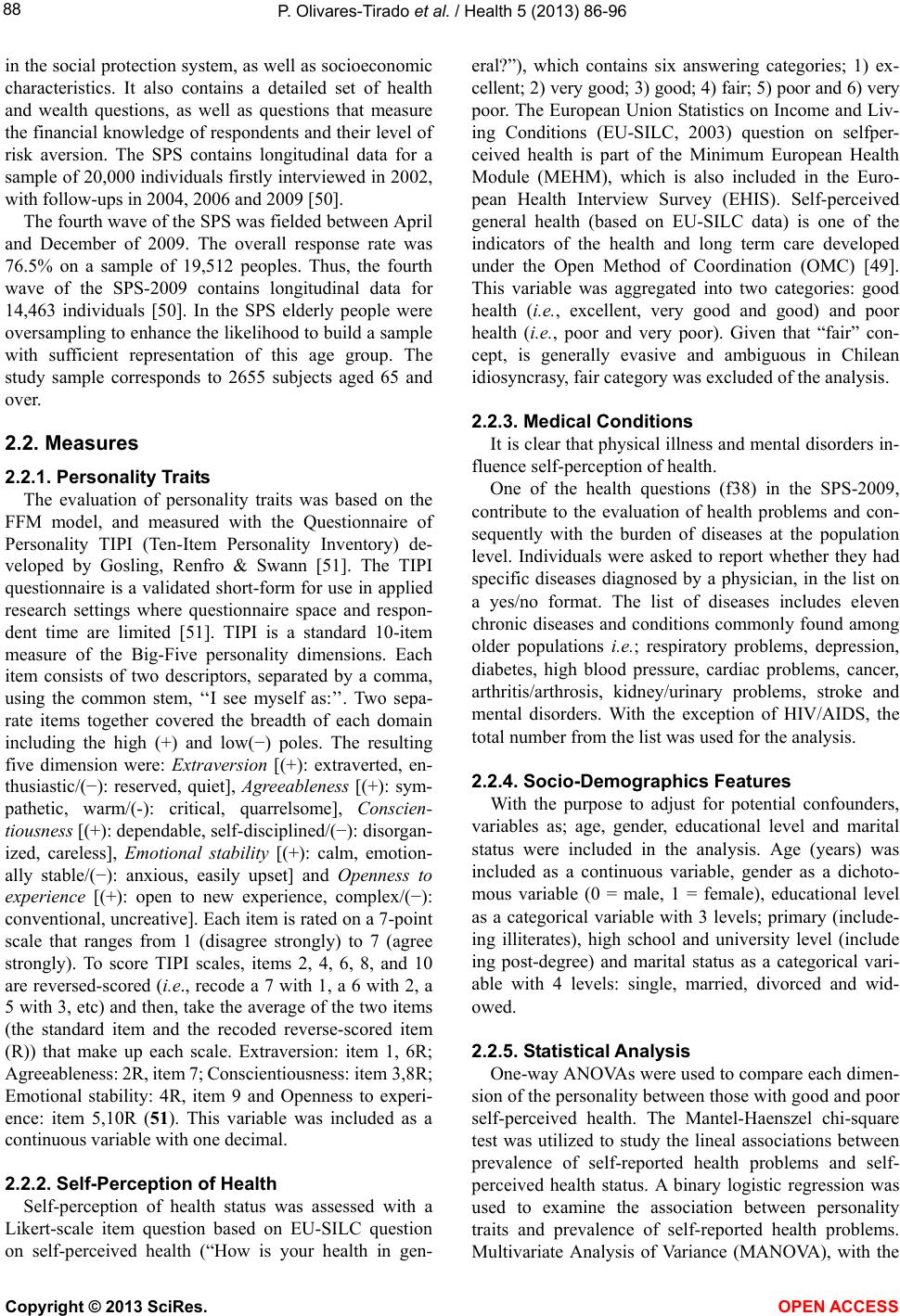

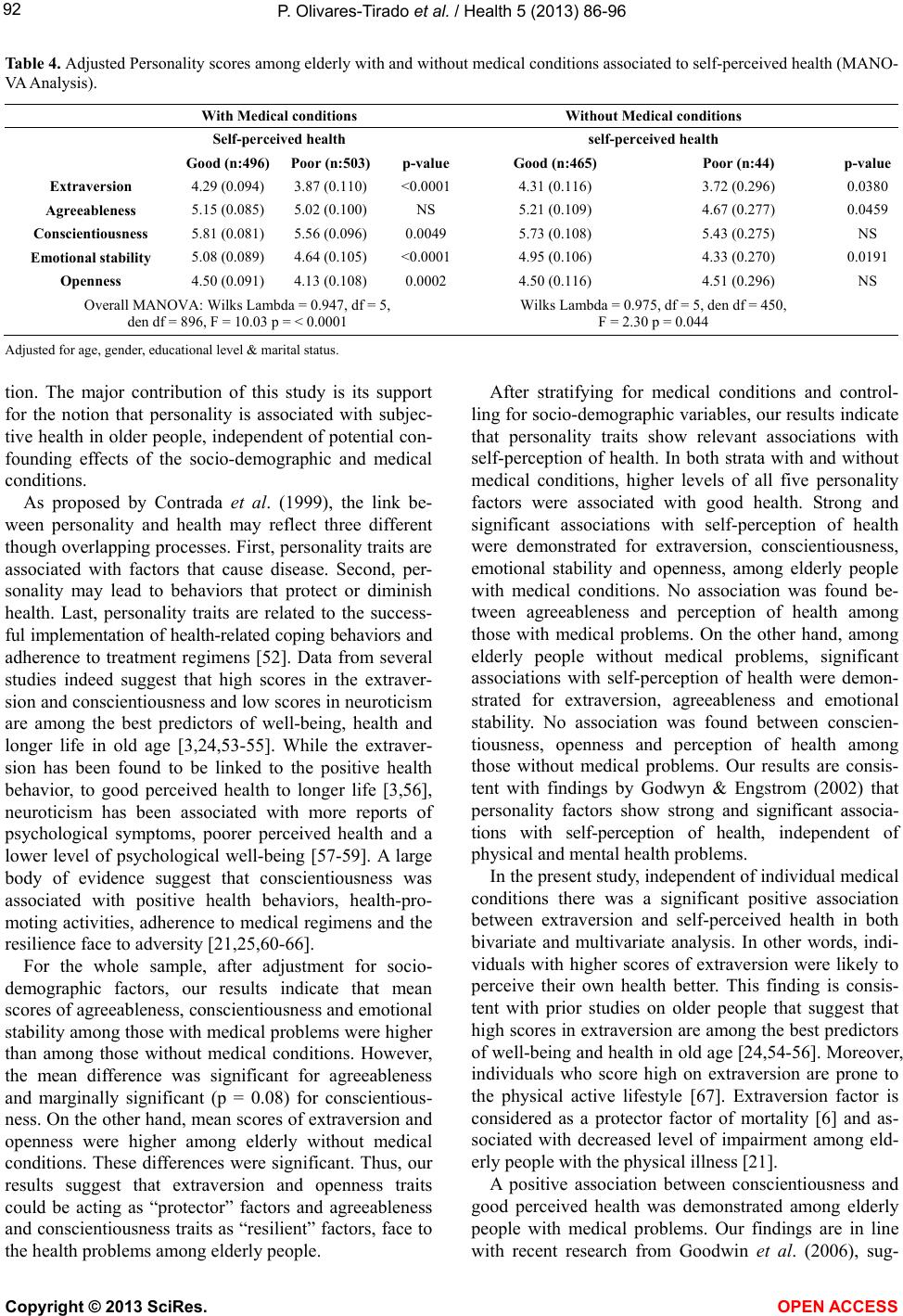

|