Journal of Cancer Therapy, 2013, 4, 1490-1498 Published Online December 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/jct) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jct.2013.410180 Open Access JCT The Prognostic Value of Minimally Involved Melanoma Sentinel Lymph Nodes* Alend Saadi1#, Didier Roulin1#, Essia Saiji2, Hanifa Bouzourene2, Nicolas Demartines1, Maurice Matter1† 1Department of Visceral Surgery, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland; 2University Institute of Pathol- ogy, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland. Email: †maurice.matter@chuv.ch Received November 26th, 2013; revised December 17th, 2013; accepted December 23rd, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Alend Saadi et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accor- dance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2013 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Alend Saadi et al. All Copyright © 2013 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. ABSTRACT Background: Sentinel node (SLN) status is the most important prognostic factor for early-stage melanoma patients. It will influence follow-up and may change therapy. Positive SLNs present different degrees of involvement so that sub- groups of patients may have minimal SLN invasion. The aim of this study was to evaluate survival in subgroups with minimally involved SLNs and to compare them to negative SLN patients. Method: SLN biopsy was performed in 499 consecutive clinically N0 patients between 1997 and 2008. Following updated recommendations from the Melanoma Group of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer, degrees of SLN involvement were fully re- assessed for two anatomopathological parameters: tumour burden according to Rotterdam criteria (<0.1 mm, 0.1 - 1.0 mm, and >1.0 mm) and microanatomic location according to Dewar (subcapsular, combined subcapsular and paren- chymal, parenchymal, multifocal, or extensive). Minimally involved SLNs were defined as those with tumor burden <0.1 mm and/or subcapsular metastasis location. Kaplan-Meier and multivariable logistic regression analyses were per- formed. Results: Out of 499 clinically N0 patients, positive SLNs were found in 123 patients (24.7 percent). With a median follow-up of 52 months (range: 9 - 146), five-year disease-free (DFS), disease-specific survival (DSS) and overall survival (OS) were 88.1, 93.9 and 89.9 percent for negative SLN patients, respectively. In minimally involved SLNs, there were 21 with tumour burden <0.1 mm, and 52 with subcapsular metastasis. Five-year DFS, DSS and OS in these sub-groups were 79.6, 86.6 and 86.6 percent, then 57.3, 69.8 and 67.8 percent respectively. DFS univariable analysis of these sub-groups compared to negative SLNs showed: (HR1.89, 95 percent CI 0.75 - 4.79; p 0.175) and (HR 3.92, 95 percent CI 2.29 - 6.71; p < 0.0001) respectively. Minimally involved sub-groups were not predictive for NSLN negativity. Conclusion: Rotterdam’s tumour burden stratification is an easy and useful prognostic factor of melanoma survival. There was a trend showing that patients with SLN tumour burden <0.1 mm have a lower survival compared to SLN negative patients. One might suggest that patients with minimally involved SLNs may not be managed similarly to negative SLN patients. Subcapsular metastasis subgroup according to the microanatomic location has statistically sig- nificant worst survival. Keywords: Metastatic Melanoma; Sentinel Node; Minimally Involved 1. Introduction Since the first report in 1992 for melanoma patients [1], sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy has become a routine procedure in specialized centers for the management of intermediate risk, clinically localized cutaneous mela- noma. Lymphatic mapping with sentinel lymphadenec- tomy is a safe and effective surgical technique with lim- ited morbidity [2]. The importance of the SLN status is now widely accepted as the most important prognostic factor [2,3]. In literature, positive SLN is found in 15 percent to 30 percent of patients [3-8]. In case of positive *Sources of support and funding for this work: none. #Both authors contributed equally to this work. †Corresponding author.  The Prognostic Value of Minimally Involved Melanoma Sentinel Lymph Nodes 1491 SLN, most centers recommend a completion lymph node dissection (CLND). However, additional positive non- sentinel lymph nodes (NSLN) are found in only about 20 percent of CLND [3,5,7-10]. This means that radical lymph node dissection, with its consecutive morbidity [11], might be unnecessary in about three quarters of patients with positive SLN. Seeking for the optimal prac- tice, the SLN status was sharpened in order to better pre- dict NSLN status, recurrence rate and survival. Different classifications of positive SLN were proposed but none of these have gathered a wide acceptance [5,7-17]. Re- cently, the EORTC Melanoma Group recommended a protocol to report the three following items per positive SLN [18]: (1) The microanatomic location of the metas- tases according to Dewar for the entire node (A = sub- capsular, B = combined subcapsular and parenchymal, C = parenchymal, D = multifocal, and E = extensive); (2) the SLN tumour burden according to the Rotterdam Cri- teria for the maximum diameter of the largest metastasis expressed as an absolute number; and (3) the SLN tu- mour burden stratified per category: <0.1 mm, 0.1 - 1.0 mm, or >1.0 mm. The aim of this retrospective study of a prospective cohort was to analyze the results of the positive SLNs in a tertiary reference center for melanoma, to investigate prognostic factors for disease-free survival (DFS), dis- ease-specific survival (DSS) and overall survival (OS) in light of the EORTC recommendations protocol and pri- mary tumour criteria, and to compare minimally involved subgroups, such as tumour burden <0.1 mm, subcapsular metastasis, and SLN negative patients. Predictability of positive NSLNs was also analyzed. 2. Patients and Methods 2.1. Patients Between October 1997 and December 2008 all consecu- tive SLN biopsy (SLNB) for melanoma patients were included prospectively in a database. SLNB was per- formed by a single surgical team at the Centre Hospi- talier Universitaire Vaudois (CHUV) in Switzerland. Inclusion criteria were primary skin melanoma >1.00 mm without palpable adenopathy and absence of distant metastases (confirmed by CT scan or PET scan). Patients with melanoma thickness <1.00 mm in the presence of specific histopathologic factors, such as ulceration, re- gression, or Clark level IV/V were also included. A CLND was usually proposed to patients with metastatic SLN. Patients with clinically metastatic lymph nodes were offered a therapeutic lymph node dissection and excluded from the present analysis. Patients with local recurrence of an earlier melanoma who also had a SLNB were excluded. The protocol of this study was accepted by the Institutional Ethical Committee. 2.2. Surgical Technique and Pathological Analysis All patients underwent SLNB according to the triple technique as previously described (3). The SLN was de- fined as any blue node, the node with the highest radio- active count, and any node with >10 percent count rate of the most radioactive node. Any enlarged (>1 cm) suspi- cious node and some adjacent nodes (mainly for ana- tomical reason) were also dissected. SLNB was followed by initial melanoma scar wide excision (WE) with safety margins of 1 cm and 2 cm according to Breslow thick- ness of < = 1 mm and >1 mm respectively. SLN(s) were sent fresh or in formaldehyde solution directly to the University Institute of Pathology. Lymph nodes were bivalved and paraffin embedded. Three slices were cut for hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) and immunohisto- chemistry (IH) staining (Melan A and protein S100) at a regular 50 m interval at least six times following a SLNB protocol (3). No PCR analysis was performed. The CLND’s nodes were only processed with H-E stain- ing. An expert team from the Department of Pathology (E.S. & H.B.) reviewed all positive SLNs for the purpose of this study, according to the EORTC Melanoma Group recommended protocol [18]. Degrees of SLN involve- ment were fully re-assessed for two anatomopathological parameters: tumour burden according to Rotterdam crite- ria (<0.1 mm, 0.1 - 1.0 mm, and >1.0 mm) and microan- atomic location according to Dewar (subcapsular, com- bined subcapsular and parenchymal, parenchymal, mul- tifocal, or extensive). Minimally involved SLNs were defined as those with tumor burden <0.1 mm and/or sub- capsular metastasis location. 2.3. Follow-Up A clinical follow-up was performed every 3 months dur- ing the first year after diagnosis, every 4 months during the second year, every 6 months during the 3rd, 4th and 5th years and then once a year. For patients with a Breslow more than 4 mm and for patients with positive SLN, a thoraco-abdominal scan was done once a year during the first five years following diagnosis. Most patients were followed at the outpatient clinic of the Oncology Unit in the same institution. Some patients were followed by their own dermatologists; their written follow-up was obtained after consent. Duration of follow-up was de- fined as time between date of SLN procedure and date of the last follow-up or death. 2.4. Statistical Analysis Quantitative variables were compared using the Student or the Mann-Whitney test. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test. Univariable analysis of po- tential prognostic factors was performed (Table 1). A Open Access JCT  The Prognostic Value of Minimally Involved Melanoma Sentinel Lymph Nodes Open Access JCT 1492 Table 1. Clinical and anatomopathological characteristics of 123 positive sentinel lymph nodes (SLNs) patients and univari- able analyses of disease-free (DFS), disease-specific (DSS) and overall survival (OS). DFS DSS OS Characteristics Level Patients N = 123HR95% CI P HR95% CIP HR 95% CIP Gender Female Male 50 73 1 2.14 1.2 - 3.8 0.008 1 2.57 1.2 - 5.3 0.011 1 2.58 1.3 - 5.1 0.007 Age (mean ) ≤65 years >65 years 84 39 1 1.68 1.0 - 2.83 0.052 1 1.50 0.8 - 2.9 0.230 1 1.57 0.9 - 2.9 0.153 Melanoma subtype Superficial spreading Nodular Acral lentiginous Others 42 50 15 16 1 1.05 1.63 0.76 0.6 - 1.9 0.7 - 3.6 0.3 - 1.9 0.870 0.220 0.545 1 1.22 1.82 0.95 0.6 - 2.5 0.6 - 5.2 0.3 - 3.0 0.601 0.265 0.935 1 1.24 1.67 1.10 0.6 - 2.5 0.6 - 4.7 0.4 - 3.1 0.544 0.331 0.861 Breslow thickness <1 mm 1.01 - 2.0 mm 2.01 - 4.0 mm >4.0 mm 4 41 49 29 1 1 1.82 1.82 1.3 - 2.5 1.3 - 2.5 <0.0001 <0.0001 1 1 3.68 3.68 1.1 - 2.3 1.1 - 2.3 0.002 0.002 1 1 1.64 1.64 1.1 - 2.4 1.1 - 2.4 0.008 0.008 Clark level III IV V 23 89 11 1 1.23 1.37 0.6 - 2.5 0.5 - 3.8 0.552 0.551 1 1.41 1.21 0.6 - 3.4 0.3 - 4.9 0.440 0.787 1 1.56 1.63 0.7 - 3.7 0.5 - 5.9 0.316 0.448 Ulceration Absent Present 49 74 1 2.21 1.3 - 3.7 0.003 1 2.16 1.1 - 4.1 0.018 1 2.38 1.3 - 4.3 0.005 Primary melanoma location Extremity Head and neck Trunk 63 5 55 1 1.68 1.09 0.5 - 5.5 0.7 - 1.8 0.393 0.729 1 2.93 1.50 0.9 - 10.1 0.8 - 2.9 0.089 0.226 1 2.41 1.32 0.7 - 8.2 0.7 - 2.5 0.157 0.379 Lymph node basin 1 >1 92 31 1 1.08 0.6 - 1.9 0.789 1 1.26 0.6 - 2.6 0.530 1 1.41 0.7 - 2.7 0.314 SLN Tumour Burden <0.1 mm 0.1 - 1 mm >1.0 mm Not available 21 33 65 4 1 2.58 4.50 0.9 - 7.3 1.8 - 11.5 0.076 0.002 1 2.14 3.35 0.7 - 6.9 1.2 - 9.7 0.203 0.026 1 2.11 3.69 0.7 - 6.8 1.3 - 10.6 0.211 0.015 SLN Microanatomic tumour location* A B C D E Not available 52 18 11 8 29 5 1 1.45 0.74 1.32 3.31 0.7 - 3.2 0.2 - 2.5 0.5 - 3.9 1.7 - 6.1 0.363 0.635 0.611 <0.0001 1 1.57 0.94 0.39 1.98 0.6 - 3.9 0.3 - 3.3 0.05 - 3.0 0.9 - 4.3 0.327 0.927 0.367 0.081 1 1.69 0.88 0.37 1.97 0.7 - 4.0 0.3 - 3.0 0.05 - 2.8 1.0 - 4.1 0.232 0.841 0.334 0.070 *SLN Microanatomic tumour location according to Dewar (8): A, subcapsular. B, combined subcapsular and parenchymal. C, parenchymal. D, multifocal or E, extensive. HR, hazard ratio. CI, confidence interval. P, significance level. multivariable logistic regression model was used for the significant factors in the univariable analyses. Survival analyses involved the Kaplan-Meier method combined with log-rang test and multivariable Cox’s proportional hazard regression models. Statistical analyses were per- formed with Stata 11 software (Stata Corp®). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. 3. Results 3.1. Patient Characteristics During the study period, 499 consecutive patients with primary skin melanoma and clinically N0 underwent a SLNB and were included in this study. Metastases to SLN(s) were detected in 123 (24.7 percent) patients. The median (range) Breslow thickness was 1.7 mm (0.3 - 15), 1.5 mm (0.3 - 15), and 2.5 mm (0.8 - 12) for all patients, SLN negative and SLN positive patients respectively. For the same groups of patients, male ratios were 274/ 499 (55 percent), 201/376 (54 percent) and 73/123 (59 percent) respectively; ulceration rates were 126/499 (25 percent), 77/376 (21 percent), 49/123 (40 percent) re- spectively. Clinical and anatomopathologic characteris- tics of the 123 SLN positive patients are presented in Table 1. All positive SLN were classified according to the recommendations from the EORTC Melanoma Group protocol published in 2009 (15). In four cases the pathological slides were not available for reassessment of the tumour burden and in five cases for the micro- anatomic location. The four SLN positive patients who had melanoma with Breslow thickness 1.0 mm had a Breslow thickness close to 1.0 mm (n = 2) or Clark level IV (n = 2). 3.2. Prognostic Factors The univariable Cox’s analysis of the 123 SLN positive  The Prognostic Value of Minimally Involved Melanoma Sentinel Lymph Nodes 1493 patients for DFS, DSS, and OS are presented in Table 1 . Breslow thickness >2.0 mm, male gender, ulceration, SLN tumour burden >= 0.1 mm, and extensive micro- anatomic metastatic location (E) were significantly asso- ciated with worse DFS, DSS, and OS (p < 0.05). An age > 65 years was also significantly associated with worse DFS. On the multivariable analysis, Breslow thickness >2.0 mm (HR 3.01, 95 percent CI 1.51 - 6.04; p 0.002/ HR 3.27, 95 percent CI 1.40 - 7.66; p 0.006/HR 3.46, 95 percent CI 1.49 - 8.05; p 0.004), ulceration (HR 1.74, 95 percent CI 0.99 - 3.06; p 0.054/HR 2.13, CI 1.07 - 4.27; p 0.032/HR 2.50, 95 percent CI 1.28 - 4.89; p 0.007), and SLN tumour burden >= 0.1 mm (HR 3.55, 95 percent CI 1.30 - 9.66; p 0.013/HR 3.04, 95 percent CI 1.03 - 8.94; p 0.044/HR 3.29, 95 percent CI 1.12 - 9.66; p 0.030) were independent significant factors lowering DFS, DSS, and OS. Male gender (HR 1.81, 95 percent CI 0.98 - 3.32; p 0.057/HR 2.95, 95 percent CI 1.39 - 6.27; p 0.005/HR 3.32, 95 percent CI 1.58 - 7.0; p 0.002) was an inde- pendent significant factor lowering DSS and OS. Exten- sive microanatomic metastatic location (E) was an inde- pendent significant factor lowering only DFS (HR 1.87, 95 percent CI 1.05 - 3.35; p 0,033). The median SLN tumour burden in the extensive microanatomic location (E) was 7 mm (range: 0.8 - 15) compared to 0.15 mm (range 0.09 - 4) in the subcapsular microanatomic loca- tion (A) (HR 3.31, 95 percent CI 1.7 - 6.1; p < 0.001). 3.3. Survival Analyses The median follow-up time for all 499 patients was 52 months (range: 9 - 146). The median follow-up time for the 123 SLN positive patients was 41 months (range: 2 - 146). The 3- and 5 - year DFS for SLN positive patients were 57.8 percent and 47.6 percent, compared to 92.3 percent and 88.1 percent respectively for patients with a negative SLN. The 3- and 5-years DSS were 77.2 percent and 61.8 percent compared to 97.2 percent and 93.9 per- cent; and OS were 75.4 percent and 59.1 percent com- pared to 95.4 percent and 89.9 percent for the same pa- tients respectively. 3.4. Sentinel Lymph Node Positive Subgroups Analyses SLN positive subgroups DFS, DSS, and OS compared to negative SLN are presented in Table 2. SLN tumour burden subgroups 0.1 - 1 mm and >1 mm were signifi- cantly associated with worse survival. However, it did not reach statistical significance for the <0.1 mm sub- group. SLN microanatomic tumour location subgroups were all constantly significantly associated with a poorer survival, except for subgroups C and D. The 3- and 5-years DFS, DSS, and OS for SLN positive subgroups compared to SLN negative patients are presented in Ta- ble 3. Tumour burden subgroups disease-free survival curves are shown in Figure 1. Global recurrence rate was 5 (24 percent), 14 (42 percent), and 43 (66 percent) for Rotterdam subgroups <0.1 mm, 0.1 - 1 mm, and >1 mm respectively. Minimally involved SLN subcapsular sub- group A presented 20 recurrences (39 percent). There were 45 recurrences (12 percent) in the negative SLN. 3.5. Predictive Factors for Non-Sentinel Lymph Node Metastasis Among the 123 patients with a positive SLN, 111 un- derwent a CLND. The procedure was not proposed to Table 2. Univariable analyses of sentinel lymph node (SLN)-positive subgroups of disease-free (DFS), disease-specific (DSS) and overall survival (OS) compared to SLN negative patients. DFS DSS OS SLN status Level NHR 95% CI P HR95% CI P HR 95% CI P SLN negative 376 1 1 1 <0.1 mm 21 1.89 0.75 - 4.790.175 2.420.84 - 6.950.100 1.43 0.51 - 3.990.493 0.1 - 1.0 mm 33 4.55 2.45 - 8.47<0.00015.412.60 - 11.26<0.00013.29 1.65 - 6.560.001 SLN Tumour Burden >1.0 mm 65 8.97 5.83 - 13.80<0.00018.885.08 - 15.56<0.00016.04 3.72 - 9.79<0.0001 A 52 3.92 2.29 - 6.71<0.00013.202.64 - 9.44<0.00014.10 1.81 - 5.68<0.0001 B 18 6.07 2.96 - 12.48<0.00015.553.57 - 19.27<0.00018.30 2.60 - 11.86<0.0001 C 11 2.71 0.84 - 8.750.095 2.971.44 - 15.830.069 4.78 0.92 - 9.590.010 D 8 5.08 1.82 - 14.170.002 1.080.25 - 13.680.942 1.85 0.15 - 7.820.545 SLN Microanatomic tumour location* E 29 13.93 8.38 - 23.17<0.00017.025.31 - 21.18<0.000110.60 3.75 - 13.14<0.0001 *SLN Microanatomic tumour location according to Dewar (8): A, subcapsular. B, combined subcapsular and parenchymal. C, parenchymal. D, multifocal or E, extensive. HR, hazard ratio. CI, confidence interval. P, significance level. Open Access JCT  The Prognostic Value of Minimally Involved Melanoma Sentinel Lymph Nodes 1494 Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank test of tumour burden subgroups disease-free survival compared to negative sentinel nodes patients. Table 3. Sentinel lymph node (SLN) subgroups primary characteristics: Breslow thickness (median and range) and ulcera- tion, the 3 and 5 years rates of disease-free (DFS), disease-specific (DSS) and overall survival (OS). 3 years 5 years SLN status Level Breslow U DFS DSS OS DFS DSS OS SLN negative 1.5 (0.3 - 15) 20%92.3 97.2 95.4 88.1 93.9 89.9 <0.1 mm 2.3 (1.1 - 9) 38%86.3 93.4 93.7 79.6 86.6 86.6 0.1 - 1 mm2.0 (1.0 - 6) 30%64.4 83.1 83.4 52.7 68.7 68.5 SLN Tumour Burden >1 mm 3.0 (0.8 - 12) 48%43.3 69.2 65.3 32.1 50.2 44.9 A 2.4 (1.0 - 9) 37%68.4 83.4 82.6 57.3 69.8 67.8 B 2.8 (1.1 - 8) 33%56.9 72.6 67.4 45.0 54.8 47.9 C 2.0 (1.2 - 6) 36%78.4 84.2 84.5 69.2 71.0 70.8 D 2.7 (1.5 - 5) 38%65.9 94.0 94.3 54.5 87.9 88.0 SLN Microanatomic Tumour location* E 3.1 (0.8 - 12) 52%32.0 66.7 63.9 22.6 47.9 44.0 *SLN Microanatomic Tumour location according to Dewar (8): A, subcapsular, B, combined subcapsular and parenchymal, C, parenchymal, D, multifocal, or E, extensive. U, ulceration. three patients due to their poor general condition, and six further patients refused the procedure. A CLND was also not proposed to three patients between 1997 and 2000 due to the very limited SLN invasion. Their SLNs were negative with H-E and had few metastatic cells detected in IH. One or more (median = 1, range = 1 - 4) positive non-sentinel nodes (NSLN) were found in 20 patients (18 percent). The univariable analysis of these patients is presented in Table 4. On the multivariable analyses, ul- ceration (OR 6.51, 95 percent CI 1.91 - 22.13; p = 0.003) Open Access JCT  The Prognostic Value of Minimally Involved Melanoma Sentinel Lymph Nodes 1495 Table 4. Predictive factors of positive non-sentinel lymph nodes (NSLNs). Positive NSLN = 20 Negative NSLN = 91 Characteristics Level N % N % OR P Gender Female Male 8 12 18 18 37 54 82 82 1 1.03 0.957 Age (mean ) ≤ 65 years > 65 years 11 9 14 26 65 26 86 74 1 2.04 0.157 Melanoma subtype Superficial spreading Nodular Acrallentiginous Others 5 11 2 2 12 25 18 13 36 33 9 13 88 75 82 87 1 2.40 1.60 1.11 0.138 0.608 0.909 Breslow thickness <1 mm 1.01 - 2.0 mm 2.01 - 4.0 mm >4.0 mm 0 4 11 5 - 10 28 19 4 37 29 21 100 90 73 81 1 1 1.57 1.57 0.135 0.135 Clark level III IV and V 3 17 14 19 19 72 86 81 1 1.50 0.552 Ulceration Absent Present 6 14 9 31 60 31 91 69 1 4.52 0.005 Primary melanoma loca- tion Extremity Head and neck Trunk 10 3 7 18 60 14 45 2 44 82 40 86 1 6.75 0.72 0.051 0.533 SLN Tumour Burden <0.1 mm 0.1 - 1 mm >1.0 mm Not available 1 5 12 2 6 17 20 16 25 49 1 94 83 80 1 3.20 3.92 0.308 0.206 SLN Microanatomic Tumour location* A B C D E Not available 6 2 2 0 8 2 13 13 22 0 28 40 14 7 7 21 2 87 87 78 100 72 1 0.95 1.90 - 2.54 0.955 0.481 - 0.123 *SLN Microanatomic tumour location according to Dewar (8): A, subcapsular. B, combined subcapsular and parenchymal. C, parenchymal. D, multifocal or E, extensive. OR, odd ratio. P, significance level. and primary local tumour in the head and neck (OR 17.83, 95 percent CI 2.02 - 157.90; p = 0.010) were sig- nificant predictive factors for NSLN positivity. The de- gree of SLN involvement, with both studied classifica- tions, was not a predictive factor of NSLN positivity. Among the 12 patients who did not undergo a CLND, four were in the minimally involved <0.1 mm subgroup and two of them recurred at 2 months and 4 years then deceased at 2 and 5 years respectively, another six pa- tients were in the minimally involved subcapsular mi- croanatomic location (A) and four of them recurred at 2, 5, 6, and 24 months while three of them deceased at 1, 2, and 3 years. 4. Discussion This single-institution-based study with surgical and an atomopathological dedicated teams confirmed that tu- mour burden stratification according to Rotterdam crite- ria is a useful prognostic factor for survival. Patients with SLN tumour burden <0.1 mm have a trend toward lower survival and toward higher recurrence rate, compared to SLN negative patients. The clinical and anatomopathologic characteristics of SLN positive patients in this study are comparable to those described in literature [7-10,13,15] in terms of age, primary melanoma location, male/female ratio, Clark level, and ulceration rate. However, the median Breslow thickness was 1.7 mm for all patients, and 2.45 mm for SLN positive patients. These Breslow data are among the lowest mentioned in literature [7,13,15], indicating that primary tumours were probably detected at an earlier stage. Despite this, 24.7 percent of metastatic SLN were detected in clinically negative patients, which is among the highest published rate [7-10,13,15]. The positive NSLN rate is comparable to those previously reported. The microanatomic location classification according to Dewar was intended to predict NSLN metastatic in- volvement in the CLND following a SLNB procedure [5]. The subgroup with subcapsular metastasis (A) is consid- ered to be in the early stage of metastatic invasion, with the hypothesis that metastatic cells have not yet contin- ued to NSLN. However, in this study, 13 percent of the Open Access JCT  The Prognostic Value of Minimally Involved Melanoma Sentinel Lymph Nodes 1496 patients with subcapsular metastasis presented a positive NSLN. Compared to negative SLN patients, the sub- groups A, B, and E were associated with a higher recur- rence rate and a poorer survival. The subgroups C and D comprised of such a small number of patients that they were therefore probably not associated with a poorer survival than negative SLN patients. Only subgroup E, with extensive metastasis, was an independent significant factor on multivariable analysis and negatively affected DFS. This was in fact partially related to the diameter, with a median SLN tumour bur- den significantly higher in the subgroup E compared to subgroup A. Additionally, the distribution of the different subgroups in this present study differed from its original description: we found 42 percent of patients with sub- capsular metastasis (i.e. subgroup A), as compared to 26 percent in Dewar’s publication. This can be explained by the fact that this cohort of patients seems to have been diagnosed at an earlier stage. One may also hypothesize that the Dewar classification is difficult to reproduce, despite the fact that expert pathologists (ES, HB) pre- cisely reviewed all slides. This suggests that microana- tomic location is not a useful tool for predicting survival or the NSLN status. Van Akkooi’s Rotterdam Criteria was specifically de- signed for survival analysis [7]. He convincingly demon- strated that the tumour burden threshold for SLN sub- micrometastases in melanoma should be <0.1 mm. With a slightly higher cut-off of <0.2 mm, the future of these patients is differed significantly [15]. Tumour burden within SLN is indeed an easy way to classify the degree of the SLN metastatic invasion in contrast to many other complicated classifications [16,19-21]. In his first publi- cations, Van Akkooi concluded that sub-micrometastases <0.1 mm could be considered as biologically false posi- tive, identical to SLN negative patients. Therefore, these patients could be spared a CLND and could be included into adjuvant therapy trials as SLN negative patients [7,22]. Van der Ploeg et al. [8-10] confirmed these con- clusions in the same institution, and mentioned seven patients from 2004 to 2008 who did not undergo CLND because of the presence of minimal SLN tumour burden (<0.1 mm). By interest, the issue of minimally involved SLN was initially also debated in this institution. Three among the earlier patients treated in this cohort were not proposed a CLND. In the present study, only tumour burden > = 0.1 mm was a significant independent factor worsening DFS, DSS and OS. Sub-micrometastases (<0.1 mm) was not a significant independent factor for survival. However, there was a trend towards worse out- comes for patients with sub-micrometastases in com- parison to SLN negative patients. It could be hypothe- sized that this trend did not reach statistical significance due to the small number of patients (21 in the sub-mi- crometastatic subgroup), therefore not permitting a gen- eralization on a larger scale. Global recurrence rates also rose following an increase of the metastatic charge ex- pressed as tumour burden. However, even in the sub- micrometastatic group, five patients recurred: four pa- tients presented initially local recurrence, and one patient had directly distant metastases. Only one patient in sub- micrometastatic subgroup had a positive NSLN. The Rotterdam criteria satisfactory allow a stratification of the prognosis of patients with positive SLN. Although CLND did not influence survival in cohort studies [23], there is no data from randomized controlled trials. That is why; the issue remains debated waiting for the ongoing prospective study MLST II results. The European con- sensus multidisciplinary based guideline 2012 did not cut the issue of CLND for sub-micrometastatic subgroup [24]. Some authors attempted to integrate various elements in scores, taking into account the primary melanoma characteristics and the metastatic charge of the SLN, but until now these scores failed to reach two goals. The first one is to find out the least invasive but the most secure care program for a subgroup of positive SLN who are unlikely to recur and have similar survival compared to negative SLN. The second goal is to identify patients with micrometastatic SLNs who have no positive NSLN and thus can be considered as negative SLN. Taking into account the present clinical data, one would challenge at this point that such a classification might be possible. As shown in this study, even a very limited SLN invasion had a trend toward lower survival and could be associ- ated with positive NSLN. If other primary tumour char- acteristic restrictions are added to the sub-microscopic subgroup, a real subgroup acting as negative SLN might be found. In this case, it would restrict this subgroup so much that it would apply to a very limited number of patients and thus lose its clinical significance. 5. Conclusion Tumour burden stratification according to Rotterdam criteria is an easy and useful prognostic factor of survival in melanoma. There was a trend showing that patients with SLN sub-micrometastases <0.1 mm had a lower sur- vival compared to SLN negative patients. One might suggest that patients with minimally involved SLNs may not be managed similarly to negative SLN patients. Our results suggest that micro-anatomic location according to Dewar is not a useful tool for predicting survival and the NSLN status 6. Acknowledgments We are grateful to Mohamed Faouzi for the statistical analysis. Open Access JCT  The Prognostic Value of Minimally Involved Melanoma Sentinel Lymph Nodes 1497 REFERENCES [1] D. L. Morton, D. R. Wen, J. H. Wong, J. S. Economou, L. A. Cagle, F. K. Storm, L. J. Foshag and A. J. Cochran, “Technical Details of Intraoperative Lymphatic Mapping for Early Stage Melanoma,” Archives of Surgery, Vol. 127, No. 4, 1992, pp. 392-399. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420040034005 [2] T. M. Johnson, V. K. Sondak, C. K. Bichakjian and M. S. Sabel, “The Role of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy for Melanoma: Evidence Assessment,” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Vol. 54, No. 1, 2006, pp. 19-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2005.09.029 [3] D. Roulin, M. Matter, P. Bady, D. Lienard, O. Gugerli, A. Boubaker, L. Bron and F. J. Lejeune, “Prognostic Value of Sentinel Node Biopsy in 327 Prospective Melanoma Patients from a Single Institution,” European Journal of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 34, No. 6, 2008, pp. 673-679. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2007.07.197 [4] M. G. Cook, M. A. Green, B. Anderson, A. M. Egger- mont, D. J. Ruiter, A. Spatz, M. W. Kissin and B. W. Powell, “The Development of Optimal Pathological As- sessment of Sentinel Lymph Nodes for Melanoma,” The Journal of Pathology, Vol. 200, No. 3, 2003, pp. 314-319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/path.1365 [5] D. J. Dewar, B. Newell, M. A. Green, A. P. Topping, B. W. Powell and M. G. Cook, “The Microanatomic Loca- tion of Metastatic Melanoma in Sentinel Lymph Nodes Predicts Nonsentinel Lymph Node Involvement,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 22, No. 16, 2004, pp. 3345- 3349. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.12.177 [6] D. L. Morton, J. F. Thompson, A. J. Cochran, N. Moz- zillo, R. Elashoff, R. Essner, O. E. Nieweg, D. F. Roses, H. J. Hoekstra, C. P. Karakousis, D. S. Reintgen, B. J. Coventry, E. C. Glass and H. J. Wang, “Sentinel-Node Biopsy or Nodal Observation in Melanoma,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 355, No. 13, 2006, pp. 1307-1317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa060992 [7] A. C. van Akkooi, Z. I. Nowecki, C. Voit, G. Schafer- Hesterberg, W. Michej, J. H. de Wilt, P. Rutkowski, C. Verhoef and A. M. Eggermont, “Sentinel Node Tumour Burden According to the Rotterdam Criteria Is the Most Important Prognostic Factor for Survival in Melanoma Patients: A Multicenter Study in 388 Patients with Posi- tive Sentinel Nodes,” Annals of Surgery, Vol. 248, No. 6, 2008, pp. 949-955. [8] A. P. van der Ploeg, A. C. van Akkooi, P. I .Schmitz, S. Koljenovic, C. Verhoef and A. M. Eggermont, “EORTC Melanoma Group Sentinel Node Protocol Identifies High Rate of Submicrometastases According to Rotterdam Criteria,” European Journal of Cancer, Vol. 46, No. 13, 2010, pp. 2414-2421. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2010.06.003 [9] A. P. van der Ploeg, A. C. van Akkooi, P. Rutkowski, Z. I. Nowecki, W. Michej, A. Mitra, J. A. Newton-Bishop, M. Cook, I. M. van der Ploeg, O. E. Nieweg, M. F. van den Hout, P. A. van Leeuwen, C. A. Voit, F. Cataldo, A. Tes- tori, C. Robert, H. J. Hoekstra, C. Verhoef, A. Spatz and A. M. Eggermont, “Prognosis in Patients with Sentinel Node-Positive Melanoma Is Accurately Defined by the Combined Rotterdam Tumor Load and Dewar Topo- graphy Criteria,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 29, No. 16, 2011, pp. 2206-2214. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.31.6760 [10] A. P. van der Ploeg, A. C. van Akkooi, L. E. Haydu, R. A. Scolyer, R. Murali, C. Verhoef, J. F. Thompson and A. M. Eggermont, “The Prognostic Significance of Sentinel Node Tumour Burden in Melanoma Patients: An Inter- national, Multicenter Study of 1539 Sentinel NodePosi- tive Melanoma Patients,” European Journal of Cancer, 2013, Article in press. [11] D. L. Morton, A. J. Cochran, J. F. Thompson, R. Elashoff, R. Essner, E. C. Glass, N. Mozzillo, O. E. Nieweg, D. F. Roses, H. J. Hoekstra, C. P. Karakousis, D. S. Reintgen, B. J. Coventry and H. J. Wang, “Sentinel Node Biopsy for Early-Stage Melanoma: Accuracy and Morbidity in MSLT-I, an International Multicenter Trial,” Annals of surgery, Vol. 242, No. 3, 2005, pp. 302-311. [12] J. E. Gershenwald, R. H. Andtbacka, V. G. Prieto, M. M. Johnson, A. H. Diwan, J. E. Lee, P. F. Mansfield, J. N. Cormier, C. W. Schacherer and M. I. Ross, “Microscopic Tumour Burden in Sentinel Lymph Nodes Predicts Syn- chronous Nonsentinel Lymph Node Involvement in Pa- tients with Melanoma,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 26, No. 26, 2008, pp. 4296-4303. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4179 [13] A. Govindarajan, D. M. Ghazarian, D. R. McCready and W. L. Leong, “Histological Features of Melanoma Senti- nel Lymph Node Metastases Associated with Status of the Completion Lymphadenectomy and Rate of Subse- quent Relapse,” Annals of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2007, pp. 906-912. http://dx.doi.org/10.1245/s10434-006-9241-3 [14] M. E. Reeves, R. Delgado, K. J. Busam, M. S. Brady and D. G. Coit, “Prediction of Nonsentinel Lymph Node Status in Melanoma,” Annals of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2003, pp. 27-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1245/ASO.2003.03.020 [15] R. P. Scheri, R. Essner, R. R. Turner, X. Ye and D. L. Morton, “Isolated Tumour Cells in the Sentinel Node Af- fect Long-Term Prognosis of Patients with Melanoma,” Annals of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 14, No. 10, 2007, pp. 2861-2866. http://dx.doi.org/10.1245/s10434-007-9472-y [16] H. Starz, K. Siedlecki and B. R. Balda, “Sentinel Lym- phonodectomy and s-Classification: A Successful Strat- egy for Better Prediction and Improvement of Outcome of Melanoma,” Annals of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 11, No. 3, 2004, pp. 162S-168S. [17] T. Francischetto, N. Spector, J. F. Neto Rezende, M. de Azevedo Antunes, S. de Oliveira Romano, I. A. Small and C. Gil Ferreira, “Influence of Sentinel Lymph Node Tumor Burden on Survival in Melanoma,” Annals of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 17, No. 4, 2010, pp. 1152-1158. http://dx.doi.org/10.1245/s10434-009-0884-8 [18] A. C. van Akkooi, A. Spatz, A. M. Eggermont, M. Mihm and M. G. Cook, “Expert Opinion in Melanoma: The Sentinel Node; EORTC Melanoma Group Recommenda- tions on Practical Methodology of the Measurement of the Microanatomic Location of Metastases and Metastatic Open Access JCT  The Prognostic Value of Minimally Involved Melanoma Sentinel Lymph Nodes Open Access JCT 1498 Tumour Burden,” European Journal of Cancer, Vol. 45, No. 16, 2009, pp. 2736-2742. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2009.08.015 [19] D. L. Morton, L. Wanek, J. A. Nizze, R. M. Elashoff and J. H. Wong, “Improved Long-Term Survival after Lym- phadenectomy of Melanoma Metastatic to Regional Nodes. Analysis of Prognostic factors in 1134 Patients from the John Wayne Cancer Clinic,” Annals of Surgery, Vol. 214, No. 4, 1991, pp. 491-499. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000658-199110000-00013 [20] A. J. Cochran, D. R. Wen, R. R. Huang, H. J. Wang, R. Elashoff and D. L. Morton, “Prediction of Metastatic Melanoma in Nonsentinel Nodes and Clinical Outcome Based on the Primary Melanoma and the Sentinel Node,” Modern Pathology, Vol. 17, No. 7, 2004, pp. 747-755. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800117 [21] S. Debarbieux, G. Duru, S. Dalle, O. Beatrix, B. Balme and L. Thomas, “Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Mela- noma: A Micromorphometric Study Relating to Prognosis and Completion Lymph Node Dissection,” The British Journal of Dermatology, Vol. 157, No. 1, 2007, pp. 58-67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07937.x [22] A. C. van Akkooi, J. H. de Wilt, C. Verhoef, P. I. Schmitz, A. N. van Geel, A. M. Eggermont and M. Kliffen, “Clini- cal Relevance of Melanoma Micrometastases (<0.1 mm) in Sentinel Nodes: Are These Nodes to be Considered Negative?” Annals of Oncology, Vol. 17, No. 10, 2006, pp. 1578-1585. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdl176 [23] A. P. van der Ploeg, A. C. van Akkooi, P. Rutkowski, M. Cook, O. E. Nieweg, C. R. Rossi, A. Testori, S. Suciu, C. Verhoef, A. M. Eggermont, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Melanoma Group, “Prognosis in Patients with Sentinel Node-Positive Mela- noma without Immediate Completion Lymph Node Dis- section,” British Journal of Surgery, Vol. 99, No. 10, 2012, pp. 1396-1405. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bjs.8878 [24] C. Garbe, K. Peris, A. Hauschild, P. Saiag, M. Middleton, A. Spatz, J. J. Grob, J. Malvehy, J. Newton-Bishop, A. Stratigos, H. Pehamberger, A. M. Eggermont, European Dermatology Forum, European Association of Dermato- Oncology, European Organization of Research and Treat- ment of Cancer, “Diagnosis and Treatment of Melanoma. European Consensus-Based Interdisciplinary Guideline —Update 2012,” European Journal of Cancer, Vol. 48, No. 15, 2012, pp. 2375-2390. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2012.06.013

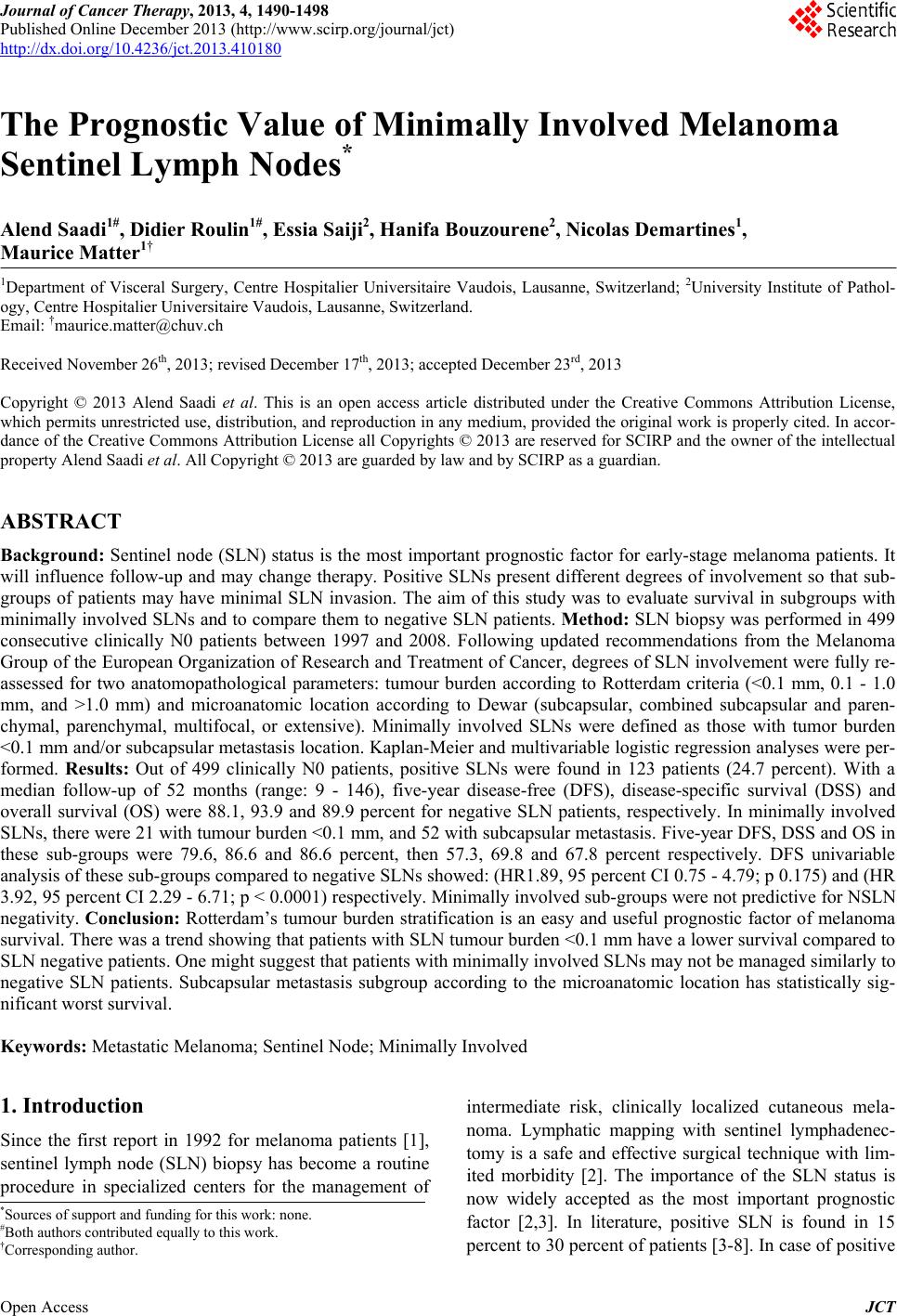

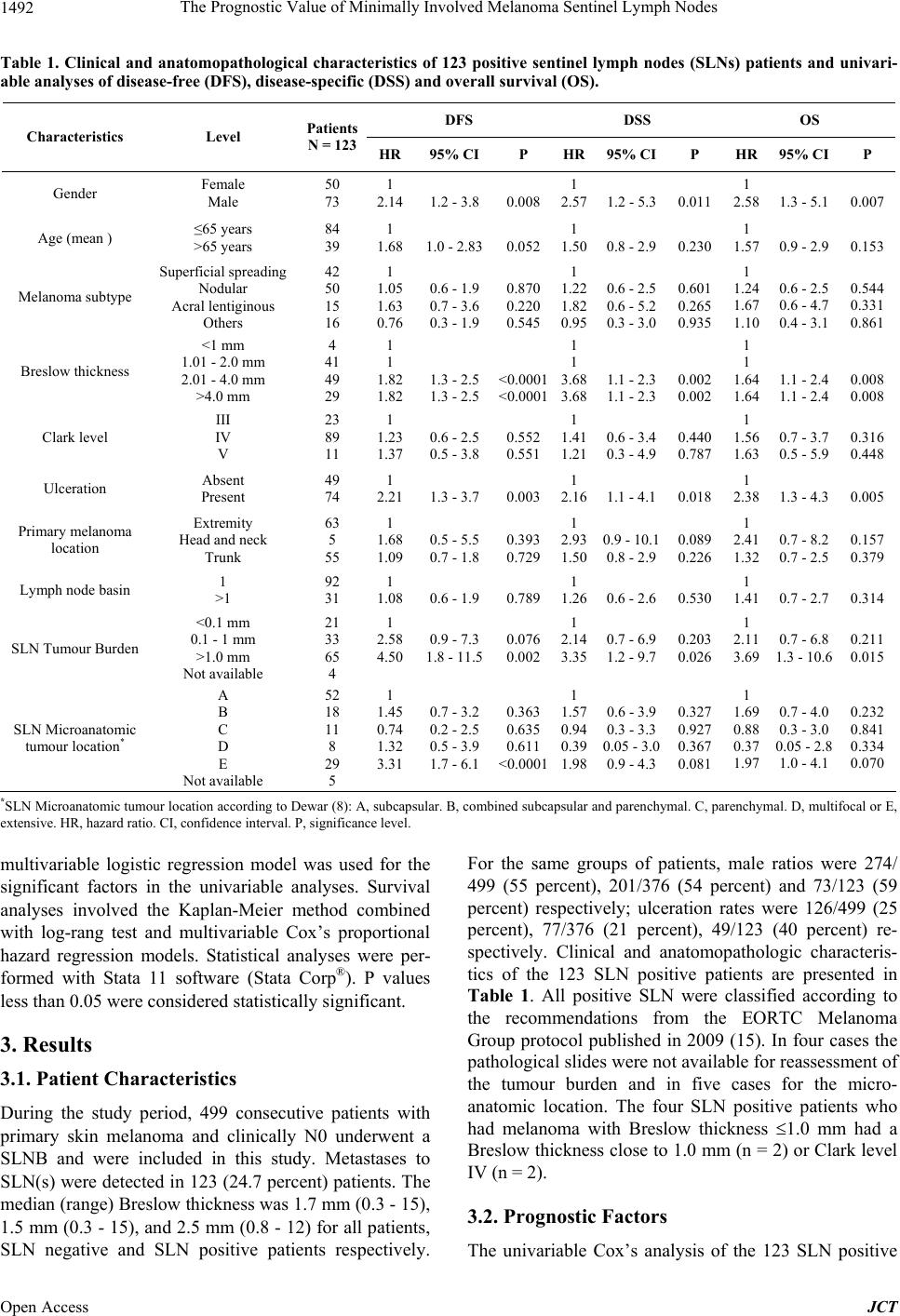

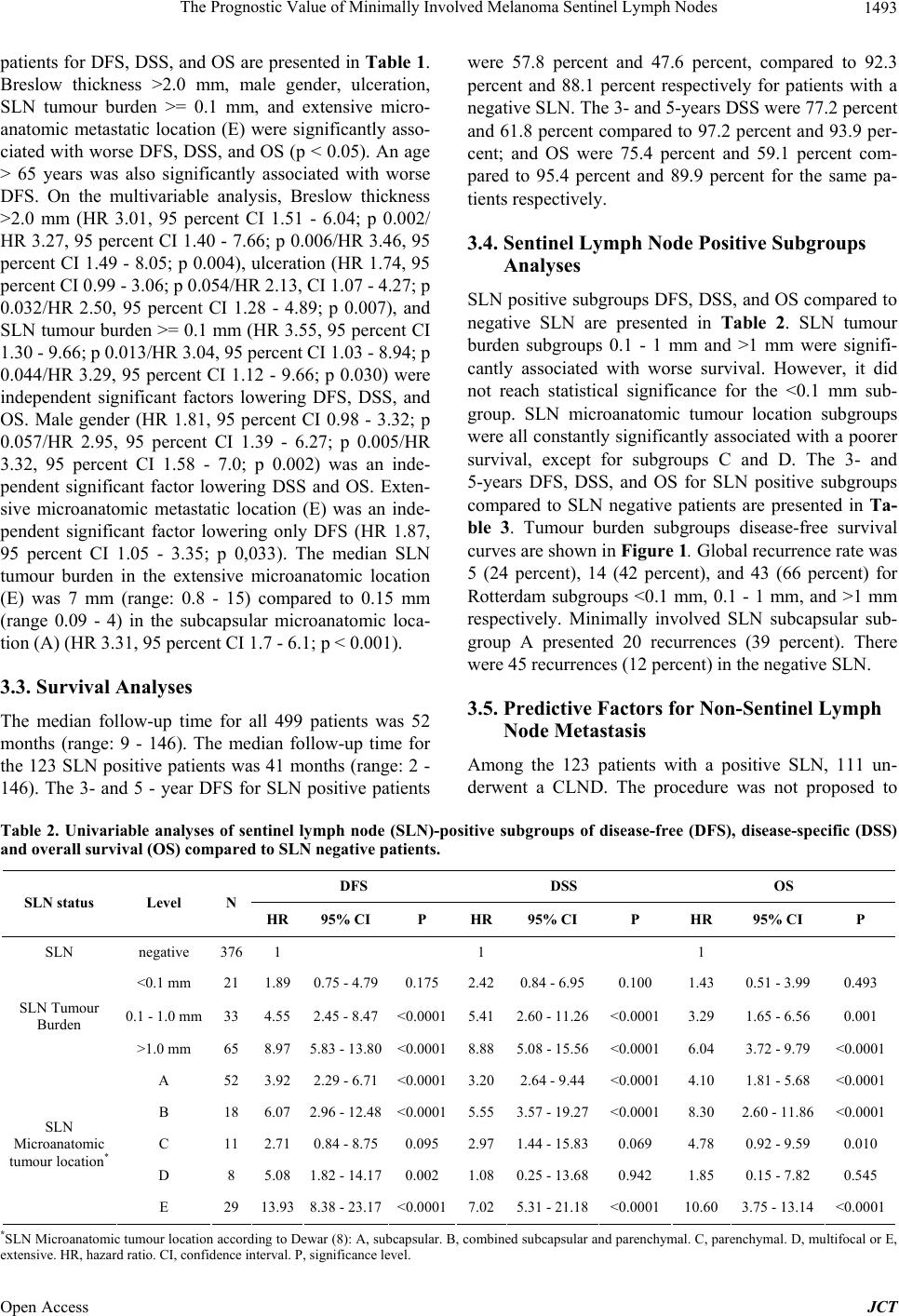

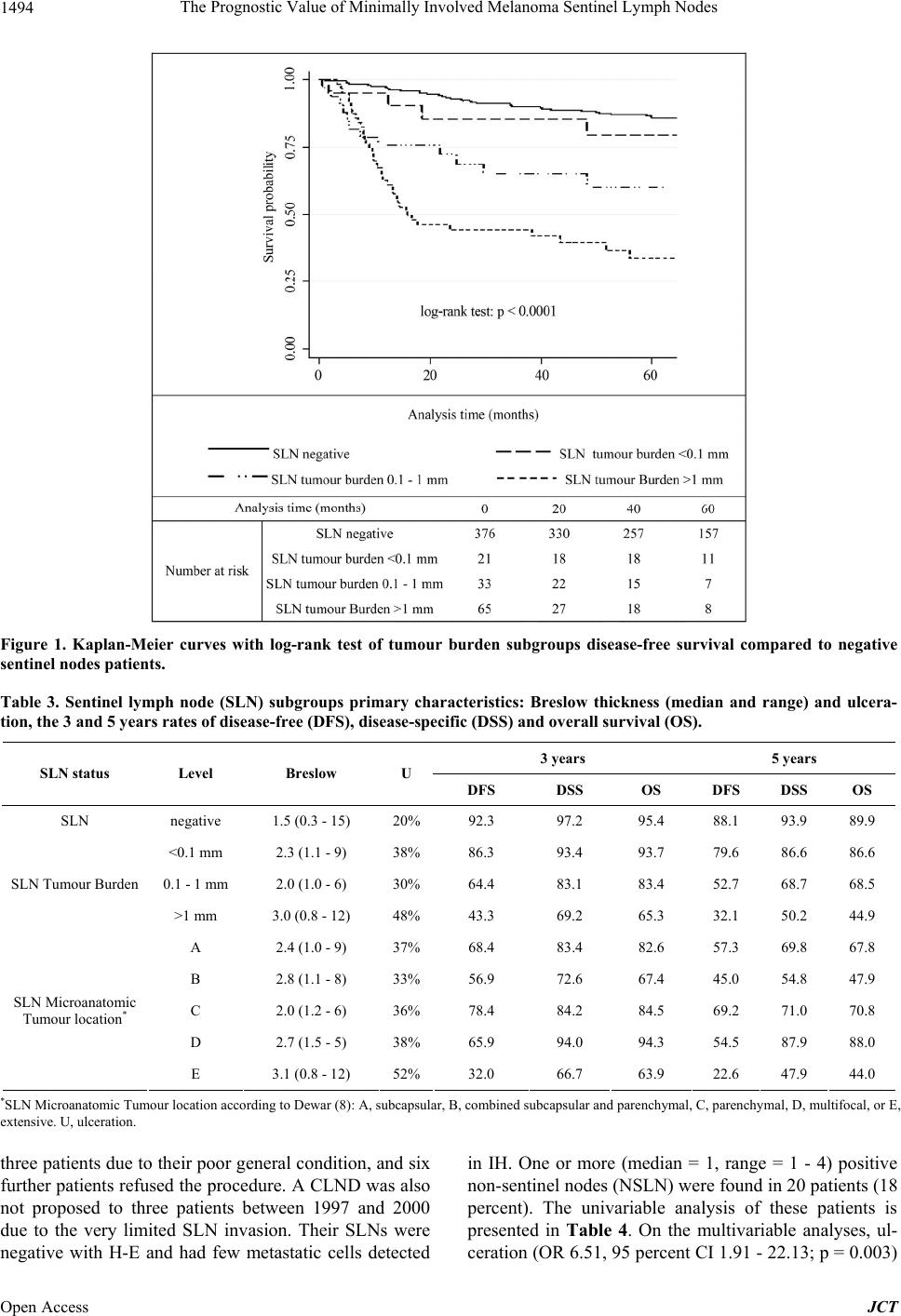

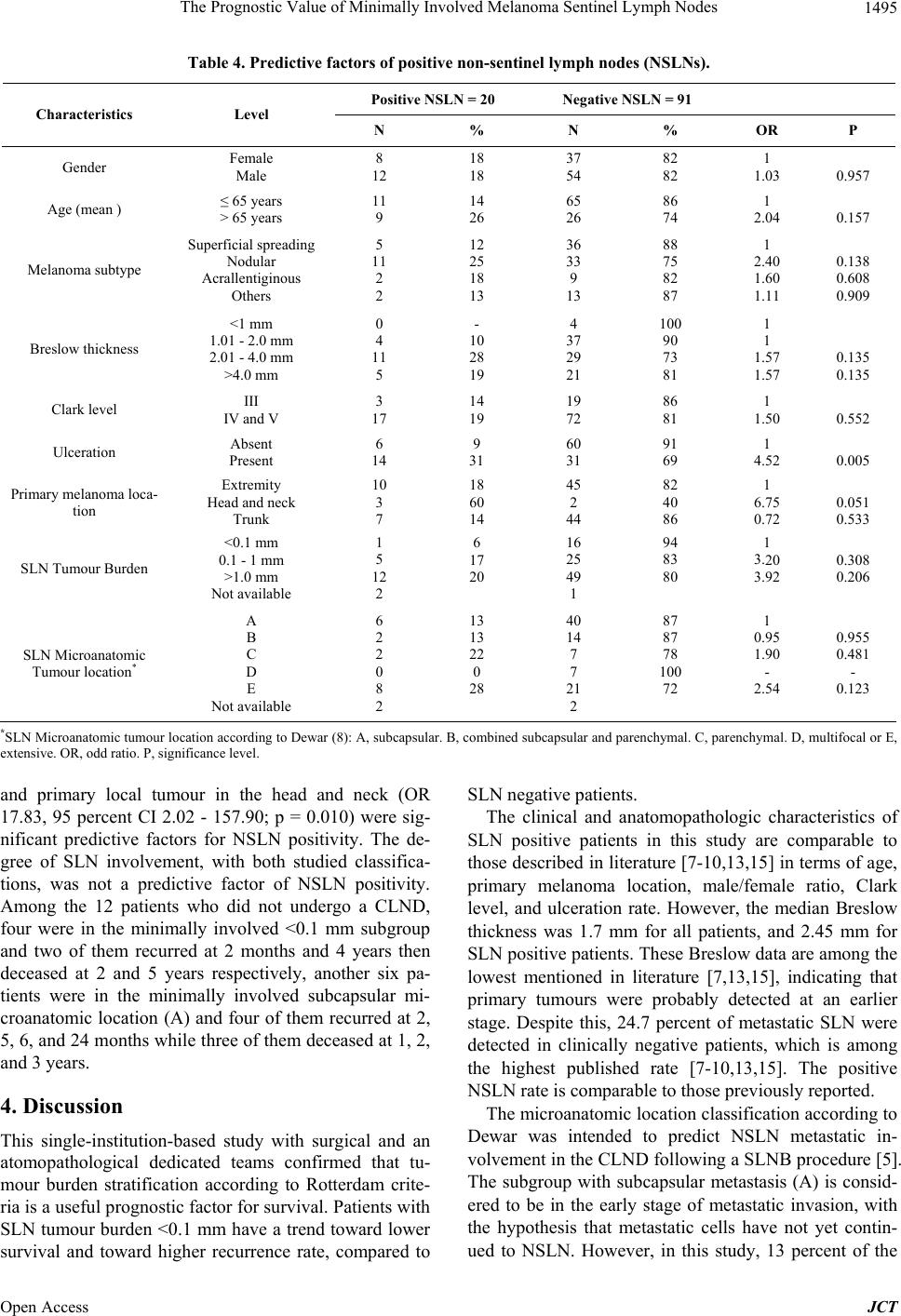

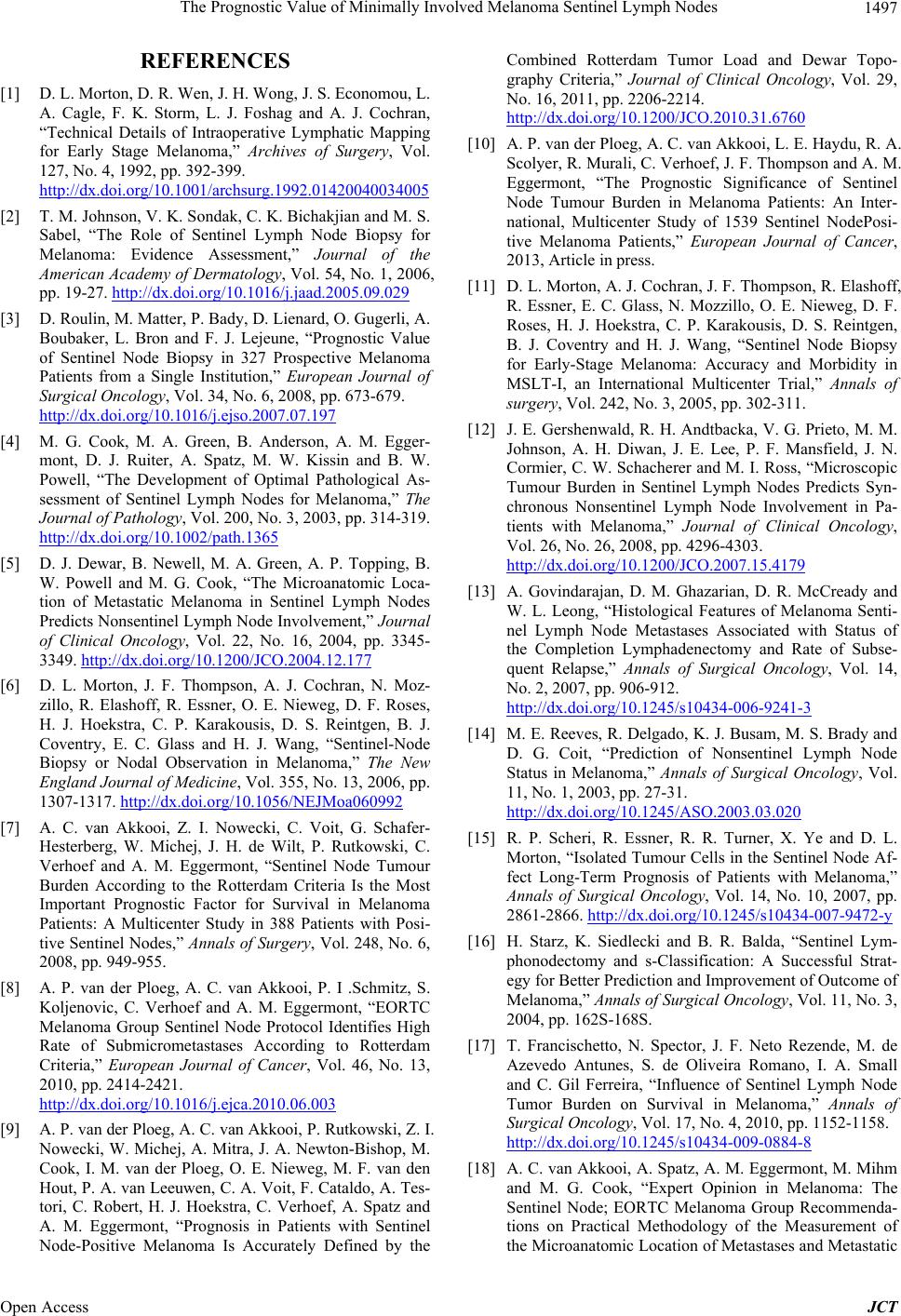

|