Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.12, 985-993 Published Online December 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.412142 Open Access 985 The Relationship between Vocational Personalities and Character Strengths in Adults Hadassah Littman-Ovadia1, Yotam Potok1, Willibald Ruch2 1Department of Behavioral Sciences and Psychology, Ariel University, Ariel, Israel 2University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland Email: hadassaho@ariel.ac.il Received August 18th, 2013; revised September 17th, 2013; accepted October 15th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Hadassah Littman-Ovadia et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2013 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Hadassah Littman-Ovadia et al. All Copyright © 2013 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. The relationship between vocational personalities and character strengths, and the contribution of both to life satisfaction were tested in an online sample of 302 Israeli adults. Hierarchical regressions indicated that love of learning explained 9.8% of the investigative personality, creativity and appreciation of beauty explained 19.6% of the artistic personality, zest and spirituality explained 14% of the social personality, and creativity explained 7.9% of enterprising personality. A bootstrapping procedure revealed that hope and gratitude fully mediated the association of social personality with life satisfaction. The theoretical and practical implications of the study findings for career counseling and development are discussed. Keywords: Vocational Personalities; Character Strengths; Life Satisfaction; Hope; Gratitude The Relationship between Vocational Personalities and Character Strengths in Adults Holland’s (1997) theory of vocational personalities is cer- tainly one of the most prevalent theories in vocational psy- chology. He suggested that people can be characterized in terms of their similarity to each six personality types (Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, and Conventional), collected referred as the RIASEC types. The more similar an individual is to each type, the more frequently that person will exhibit the talents and traits of that type. Both individuals and their environments vary in their relation to the six types, and can be characterized by resemblance to each of the six types or by their three most dominant types (3-letter Holland code). Peterson and Seligman’s (2004) theory of character streng- ths suggested that daily deployment of character strengths pro- mote optimal human functioning in the full array of life do- mains. Strengths are durable positive individual characteristics; represent what a person can do and is able to be; strengths have moral value and are acquired and developed dynamically; and most people are characterized by specific strengths (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Character strengths might also have relevance to work—a substantial area of human life which provides relatively vast opportunities for fulfilling individuals’ potential and for achieving a sense of purpose and meaning in life (Ryan & Deci, 2001). For this reason it is interesting to study the relationship between vocational personalities and character strengths. Vocational Personalities According to Holland’s theory, people are attracted to work environments whose features fit their vocational personalities. Agreement between a person’s vocational personality and his or her work environment is described as congruence. Holland also represented degrees of consistency by displaying each of the six types in a two-dimensional hexagonal structure. Individuals whose first two letters of their Holland code are proximal to each other on the hexagon are expected to be more consistent than individuals described by types that are further apart. Holland’s (1997) concept of differentiation states that people who resemble a single type will have a distinct profile and have an easier time making career choices. The realistic type is described as an asocial, conforming, frank, genuine, hardheaded, inflexible, materialistic, natural, normal, persistent, practical, self-effacing, thrifty, uninsightful and uninvolved. The investigative type is described as ana- lytical, cautious, complex, critical, curious, independent, inte- llectual, introspective, pessimistic, rational, reserved, retiring, unassuming, unpopular and precise. The artistic type is descri- bed as complicated, disorderly, emotional, expressive, idealistic, impractical, impulsive, independent, introspective, intuitive, nonconforming, open, original and sensitive. The social type is described as ascendant, cooperative, empathic, friendly, ge- nerous, helpful, idealistic, kind, patient, persuasive, responsible, sociable, tactful, understanding and warm. The enterprising type is described as acquisitive, adventurous, agreeable, am- bitious, domineering, energetic, excitement seeking, exhibi- tionistic, extroverted, flirtatious, optimistic, self-confident, so- ciable and talkative. Finally, the conventional type is described as careful, conforming, conscientious, defensive, efficient, inflexible, inhibited, methodical, obedient, orderly, persistent, practical, prudish, thrifty, unimaginative (Holland, Fritzsche, & Powell, 1994). To assess individual differences in the RIASEC, Holland developed the Self-Directed Search inventory (SDS;  H. LITTMAN-OVADIA ET AL. Holland et al., 1994). Holland’s RIASEC has been found to be related to theo- retically predictable ways to the Big Five personality dimen- sions. Gottfredson, Jones, and Holland (1993) found that social and enterprising vocational personality was positively co- rrelated with extraversion; investigative and artistic persona- lity was positively correlated with openness; and conventional personality was correlated with conscientiousness. A more re- cent meta-analysis of RIASEC/Big Five relations supported positive associations between pairs of personalities and Big Five factors (social/extraversion and agreeableness, enter- prising/extraversion, investigative/openness and artistic/open- ness), although this analysis did not support the conven- tional/conscientiousness association (Larson, Rottinghaus, & Borgen, 2002). Character S trengths Character strengths are “… positive traits reflected in thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. They exist in degrees and can be measured as individual differences” (Park, Peterson, & Seligman, 2004, p. 603). Based on a comprehensive literature review and professional consensus, Peterson and Seligman (2004) developed a classification of character strengths. Their classification, called Values In Action (VIA), includes 24 character strengths and each related to one of the following six broader virtues: a) the virtue of wisdom and knowledge includes the strengths of creativity, curiosity, open-mindedness, love of learning, perspective; b) the virtue of courage includes the strengths of bravery, integrity, persistence, zest; c) the virtue of humanity includes the strengths of kindness, love, social intelligence; d) the virtue of justice includes the strengths of fairness, leadership, teamwork); e) the virtue of temperance includes the strengths of forgiveness, modesty, prudence, self-regulation; and f) the virtue of transcendence includes the strengths of appreciation of beauty, gratitude, hope, humor, spirituality. To assess individual differences in the 24 VIA strengths in adults, Peterson, Park, and Seligman (2005) developed the Values in Action-Inventory of Strengths (VIA- IS). Peterson and Seligman (2004) acknowledged that there are some clear theoretical correspondences between strengths and personality traits, as reflected in the Big Five personality dimensions. Recently, character strengths have been found to be related in theoretically predictable ways to the Big Five personality dimensions. Specifically, appreciation of beauty, love of learning, creativity and curiosity were highly asso- ciated with openness; teamwork and kindness were highly associated with agreeableness; and persistence, self-re-gulation, honesty, fairness and forgiveness were highly associated with conscientiousness (Littman-Ovadia & Lavy, 2012). Aims of the Study Expected relationships between vocational personalities and character strengths stem both from similarities in their theo- retical descriptions and from previous studies, mentioned above, which have found relationships between vocational per- sonalities and personality dimensions on the one hand, and between character strengths and personality dimensions on the other. However, only one study to date (Proyer, Sidler, Weber, & Ruch, 2012) examined, among adolescents, the relationships between Holland’s vocational personalities and Values In Action (VIA) strengths (Peterson & Seligman, 2004); An examination of these relations among adults is lacking. A better understanding of the relationships between voca- tional personalities and character strengths is needed for both theoretical and practical reasons. Recently, Harzer and Ruch (2012, in press) provided initial evidence that congruence be- tween job demands and personal strengths might play a role in a variety of positive experiences at work (job satisfaction, pleasure, engagement, and meaning). Thus, “strength-related congruence” is important, similar to Holland’s “personalities- related congruence” and strengths might be added to the list of characteristics that needs consideration when understanding and counseling for greater job satisfaction. This raises a question on the overlap between vocational personalities and character strengths. A better understanding of the relationships between vocational personalities and strengths may also have several practical implications, as suggested by Proyer et al. (2012). First, it may be useful to understand these relationships when working with clients on their strengths or for facilitating career decision-making processes. Second, it may be beneficial to clients to consider the fit between strengths derived from a well-established classification scheme and preferences for vocations in the counseling process (e.g., social intelligence or kindness and social vocational personality). Third, vocational personalities strengths congruence is relevant for placement decisions and consequences, and a focus on employees’ streng- ths may facilitate work engagement and elicit positive emo- tions. The present study was designed to explore the relationships between vocational personalities and character strengths. More specifically, we hypothesized the following associations: rea- listic/persistence, investigative/love of learning, curiosity and prudence, artistic/creativity and beauty, social/social intelli- gence, kindness, love, teamwork, gratitude, hope and zest, enterprising/bravery, leadership, hope and zest. The present study was designed also to test the combined contribution of vocational personalities and character streng- ths to life satisfaction, a central component of subjective well- being (SWB), which has been a fundamental human concern since as early as the sixth century B.C., when Greek thinkers studied human flourishing or living well (“eudemonia”). Interest in life satisfaction has continued to the present day, under a variety of terms and methodologies (e.g., Diener, Eunkook, Lucas, & Smith, 1999; Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, & Schkade, 2005). More recently, the study of life satisfaction has focused on its relationship to personality, which was found to be one of its foremost predictors (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998; Steel, Schmidt, & Shultz, 2008). In an attempt to explain why personality is important for understanding life satisfaction, Steel et al (2008) suggested that personality helps explain the happiness-income paradox, or why life satisfaction remains sta- ble or even declines in countries or people who become very wealthy. Research in the field of personality indicates that certain dimensions of personality are related to life satisfaction. Specifically, higher levels of extraversion and agreeableness have been linked to greater life satisfaction (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998; Diener, Oishi, & Lucas, 2003). While a relationship has been found between life satisfaction and most character strengths (e.g., Littman-Ovadia & Lavy, 2012; Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Ruch, Proyer, Harzer, Park, Peterson, & Seligman, 2010), life satisfaction has been rarely linked to Open Access 986  H. LITTMAN-OVADIA ET AL. vocational personalities, although there is a large body of literature linking extraversion and agreeableness to social per- sonality (Barrick, Mount, & Gupta, 2003; Gottfredson et al., 1993; Larson et al., 2002), and although there is also evidence from the studies of the meaning in life and from studies of positive interventions that love is strongly related to life satisfaction (e.g., Lavy & Littman-Ovadia, 2011) and that doing something for others or for a higher good is gratifying and fosters life satisfaction (Peterson, 2006). Social personality entails love and doing good for others; due to this small overlap a small positive association between social personality and life satisfaction can be expected. However, in the only research that tested direct associations between Holland’s vocational per- sonalities and life satisfaction, regardless of the level of con- gruence between vocational personalities and environment type (Cotter & Fouad, 2011), no significant correlations were found. Considering the large body of literature linking extraversion and agreeableness to social personality, which includes love and doing good for others (Larson et al., 2002) on one hand, and to life satisfaction (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998; Diener et al., 2003) on the other hand, we aimed to reexamine the hypothesis concerning a direct link between social personality and life satisfaction. Furthermore, we also aimed to explore, for the first time, if certain character strengths mediated the social per- sonality-life satisfaction association. Although positive psychology assumes that the enactment of any character strength is fulfilling (Peterson & Seligman, 2004), past research shows that certain character strengths are more robustly correlated with life satisfaction than others. Spe- cifically, studies have shown that the five character strengths most strongly related to life satisfaction are love, hope, gra- titude, curiosity, and zest (e.g., Littman-Ovadia & Lavy, 2012; Park et al., 2004; Park & Peterson, 2008). Moreover, these strengths foreshadowed life satisfaction measured months later, even when controlling for initial levels of strengths (Park & Peterson, 2008). We hypothesized that the association between social personality and life satisfaction is mediated by four of these character strengths (love, hope, gratitude, and zest). Curiosity was not included in our mediation hypothesis because curiosity was not hypothesized to be associated with the social personality (Holland et al., 1994). Method Participants The study surveyed 302 Jewish Israeli individuals (99 men, 203 women), whose ages ranged from 18 to 67 years (Mean = 33.16, SD = 11.57). Of the participants, 137 (45.4%) were married, 127 (42.1%) were single, 27 (8.9%) were divorced, and 11 (3.6%) were widowed. Measures The VIA Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS; Peterson & Selig- man, 2004). The Hebrew version of the VIA-IS was used in this study (Littman-Ovadia & Lavy, 2012). This instrument assesses 24 character strengths. Each strength is evaluated by 10 items, creating a total of 240 items (e.g., “Being able to come up with new and different ideas is one of my strong points” for creativity; “I never quit a task before it is done” for persistence). Participants rate the extent to which each item describes them on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Scale scores were averaged across items, yielding 24 scores for each participant, representing partici- pants’ ratings of each of the 24 strengths. In the current study, scale reliabilities were satisfactory for all 24 subscales (Cron- bach’s alphas ranged from 0.70 to 0.87). The Self-Directed Search inventory (SDS; Holland et al., 1994). The Hebrew version of the SDS was used in this study (Meir & Hasson, 1982). This instrument assesses vocational personalities by activities, competencies and occupations repre- sent RIASEC personality types. The total score for each type (ranging from 0 to 36) reflects the degree to which a respondent resembles the respective prototype personality. In the current study, scale reliabilities ranged from 0.85 to 0.92. The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffen, 1985). The Hebrew version of the SWLS was used in this study (Anaby, Jarus, & Zumbo, 2009). This instrument assesses respondent’s global level of satisfaction. Participants rate their agreement with five statements (e.g., “So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life”) on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Overall scores range from 5 (extremely dissatisfied) to 35 (extremely satisfied). The coefficient alpha for the current study was 0.90. Procedure and Data Collection We obtained our data from randomly selected community- based participants through online electronic mail and social networks. The electronic message included a cover letter and a link to an electronic survey. Participants completed the ques- tionnaires voluntarily, after they completed the informed con- sent form and noted their interest to receive optional indi- vidual feedback on their profile of personalities and character strengths. All data were collected online. Contact information (e-mail) was given in case of any ques- stions. The average time to complete the questionnaires was 60 minutes. Results In order to assess gender differences on personalities, char- acter strengths, and life satisfaction we used effect size as sug- gested by Cohen (1992). To assess the impact of age, correla- tions were computed (see Table 1). Results from effect size calculations revealed non negligible mean differences in several variables. Women scored higher than men on persistence, hon- esty, kindness, love, teamwork, prudence, appreciation of beau- ty, gratitude, spirituality, modesty, forgiveness, and subjective well-being. Men scored higher than women on realistic, invest- tigative and conventional vocational personalities. Furthermore, negative associations with age were found for spirituality and social vocational personality. Consequently, we controlled for age and gender in our regression analyses. Associations of Vocational Personalities with Character Strengths an d Life Sati sfaction We computed Pearson correlations of the six personalities with the 24 character strengths (see Table 2). Most, but not all, of these correlations are negligible (r < 0.10) or small (r < 0.30). R esults show that Realistic personality was associated with Open Access 987  H. LITTMAN-OVADIA ET AL. Open Access 988 Table 1. Means, standard deviations, Pearson correlations with age and gender differences of character strengths, vocational interests and SWLS. Total Man Women Difference Scale M SD Age M SD M SD d Love of Learning 3.82 0.60 0.16** 3.86 0.54 3.79 0.63 - Curiosity 4.00 0.56 0.13* 4.02 0.54 3.99 0.57 - Open Mindedness 3.93 0.50 0.00 3.88 0.53 3.95 0.49 - Creativity 3.76 0.69 0.08 3.83 0.66 3.72 0.70 - Social Intelligence 3.90 0.51 −0.07 3.83 0.55 3.93 0.48 - Perspective 4.02 0.48 −0.08 3.99 0.46 4.03 0.49 - Bravery 3.67 0.51 0.07 3.70 0.55 3.65 0.48 - Persistence 3.60 0.66 0.01 3.47 0.74 3.67 0.62 0.29 Honesty 3.94 0.50 0.02 3.85 0.49 3.99 0.51 0.27 Kindness 3.95 0.60 −0.05 3.82 0.74 4.01 0.51 0.27 Love 3.96 0.57 −-0.08 3.81 0.62 4.03 0.53 0.38 Teamwork 3.73 0.57 −0.04 3.63 0.53 3.78 0.53 0.28 Fairness 3.94 0.59 0.10 3.88 0.67 3.97 0.56 - Leadership 3.67 0.53 0.02 3.59 0.54 3.71 0.51 - Self-Regulation 3.37 0.58 0.01 3.28 0.57 3.42 0.58 - Prudence 3.50 0.59 −0.02 3.36 0.51 3.56 0.57 0.36 Appreciation of Beauty 3.67 0.68 −0.02 3.49 0.67 3.75 0.68 0.38 Gratitude 3.90 0.62 −0.11* 3.66 0.69 4.02 0.55 0.57 Hope 3.75 0.61 −0.05 3.66 0.64 3.80 0.59 - Spirituality 3.69 0.83 −0.28*** 3.37 0.86 3.85 0.76 0.59 Modesty 3.38 0.71 0.02 3.22 0.75 3.46 0.67 0.34 Humor 3.74 0.61 −0.02 3.72 0.60 3.75 0.62 - Zest 3.84 0.56 −0.01 3.77 0.58 3.87 0.55 - Forgiveness 3.63 0.63 −0.05 3.47 0.67 3.71 0.59 0.38 Realistic 13.28 7.2 0.05 16.85 7.4 11.54 6.5 0.76 Investigative 15.68 8.5 −0.06 18.06 8.5 14.52 8.3 0.42 Artistic 20.07 8.8 −0.10 18.96 8.4 20.62 8.6 - Social 23.65 6.6 −0.24*** 23.10 7.2 23.91 6.5 - Enterprising 17.15 7.8 −0.02 18.52 8.4 16.48 7.5 - Conventional 13.76 6.1 0.02 15.07 6.4 13.13 5.8 0.31 SWLS 5.13 1.2 0.00 4.9 1.3 5.23 1.1 0.25 Note: N = 302 (man = 99; coded as 0, women = 203; coded as 1). M mean, SD standard deviation, d’ Cohen’s d. All negligible d’ values were omitted. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. love of learning, curiosity, creativity, bravery, prudence, grati- tude and modesty; investigative personality was associated with love of learning and curiosity, open mindedness, creativity, bravery, and modesty; Artistic personality was associated with love of learning, curiosity, creativity, social intelligence, per- spective, bravery, kindness, love, teamwork, fairness, leader- ship, appreciation of beauty, gratitude, hope, spirituality, humor, zest and forgiveness; Social personality was associated with love of learning, curiosity, creativity, social intelligence, per- spective, bravery, kindness, love, teamwork, fairness, leader- ship, appreciation of beauty, gratitude, hope, spirituality, humor, zest and forgiveness; Enterprising personality was associated with love of learning, curiosity, creativity, social intelligence, bravery, persistence, leadership, self regulation, modesty and zest; Conventional personality was associated with social intel- ligence and self regulation. Hypothesis 1 was supported. Apart from Conventional personality, which had a very small negative association with life satisfaction (see Table 2), Social personality was the only personality associated with life satis- faction. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was fully supported. Explainin g Vocation al Personaliti e s fr om Character Strengths To explore the strongest contributors of those vocational per- sonalities found to be correlated with strengths, four multiple hierarchical regression analyses were conducted with in- vestigative, artistic, social and enterprising personalities as dependent variables (realistic and conventional personalities were excluded due to small, r < 0.20, direct associations with strengths). In each analysis, the dependant variable was explained by entering age and gender in the first step of the regression (method: enter), to control for potential effects of demographics; in the second step, the strengths found to be  H. LITTMAN-OVADIA ET AL. Table 2. Pearson correlations between character strengths, vocational interests and SWLS. Realistic Investigative Artistic Social Enterprising Conventional SWLS Love of Learning 0.15** 0.30*** 0.30*** 0.20*** 0.21*** 0.10 0.20*** Curiosity 0.12* 0.24*** 0.33*** 0.20*** 0.13* −0.01 0.25*** Open Mindedness 0.03 0.14** 0.14* 0.10 0.08 0.07 0.15** Creativity 0.18** 0.17** 0.34*** 0.15** 0.29*** 0.00 0.14** Social Intelligence −0.10 −0.08 0.23*** 0.19*** 0.13* 0.13* 0.25*** Perspective −0.10 0.09 0.19*** 0.13* 0.05 −0.04 0.24*** Bravery 0.15** 0.12* 0.27*** 0.16** 0.16** 0.03 0.14** Persistence 0.07 0.05 0.09 0.08 0.19*** 0.05 0.19*** Honesty 0.03 −0.03 0.00 0.02 0.06 0.06 0.22*** Kindness −0.03 −0.03 0.19*** 0.29*** 0.05 0.03 0.31*** Love −0.05 −0.04 0.21*** 0.24*** 0.06 −0.02 0.31*** Teamwork −0.10 −0.04 0.11* 0.20*** 0.10 0.02 0.24*** Fairness −0.02 0.03 0.11* 0.17** 0.00 −0.02 0.21*** Leadership 0.03 −0.01 0.22*** 0.22*** 0.13* −0.02 0.25*** Self-Regulation 0.08 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.11* 0.11* 0.24*** Prudence −0.12* −0.01 −0.10 −0.02 −0.08 0.06 0.21*** Appreciation of Beauty −0.03 0.03 0.37*** 0.27*** 0.04 −0.06 0.20*** Gratitude −0.11* −0.07 0.29*** 0.28*** 0.01 −0.10 0.41*** Hope −0.01 0.05 0.20*** 0.24*** 0.08 −0.01 0.44*** Spirituality −0.11* −0.07 0.24*** 0.35*** −0.06 −0.08 0.26*** Modesty −0.08 −0.11* −0.10 -0.04 −0.16** −0.04 0.17** Humor −0.01 0.04 0.23*** 0.17** 0.09 −0.01 0.24*** Zest 0.07 0.00 0.29*** 0.30*** 0.20*** −0.04 0.36*** Forgiveness 0.04 −0.06 0.18** 0.16** −0.02 0.04 0.25*** SWLS −0.05 −0.08 0.09 0.25*** −0.04 −0.12* 1 Note: N = 302. SWLS satisfaction with life scale. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. correlated with the dependant variable were entered into the equation (method: stepwise). As can be observed from Table 2, some of the character strengths share their variance with several personalities and were entered into more than one regression analysis. Accordingly, we checked for problems associated with multi-collinearity on all four analyses. Furthermore, re- sults yielded significant contributions only after Bonferroni correction. Table 3 shows that age, gender and love of learning explained 15.4% of the variance of investigative personality; Appreciation of beauty and creativity explained 20.9% of the variance of the artistic personality; Age, zest and spirituality explained 20.1% of the variance of the social personality; and creativity explained 9.8% of the variance of enterprising. Do Love, Gratitude, Hope and Zest Mediate the Association between Social Personality and Life Satisfaction? A multiple mediation model procedure, following Preacher and Hayes (2008), was performed to examine a mediation link between social personality and life satisfaction (Hypothesis 3). In this procedure, the progression from one step to the next is contingent on obtaining significant results in the preceding step. The first step requires that the independent variable associates with the dependent variable. When entered into a regression analysis, social personality significantly predicted life satis- faction (β = 0.25). The second step requires the independent variable to associate with the mediating variables. Results of the regression analyses show that social personality predicts all mediators: love, hope, gratitude and zest (β = 0.24, 0.24, 0.28 and 0.30, respectively). The third step requires the mediators to associate with the outcome variable. Regression analyses showed that gratitude and hope were significantly associated with life satisfaction (β = 0.21 and 0.28, respectively). Love and zest showed no significant association with life satisfaction and were therefore excluded from further analyses. The fourth step requires the mediation paths to be significant. For this step, we used an accelerated-bias-corrected-bootstrap analysis proce- dure (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). This procedure examines whe- ther an indirect path is significantly different from 0, by pro- ducing a confidence interval (CI) for the indirect effect, in this case, with a confidence level of 95%. A mediation path is sig- nificant when the CI does not include 0. The bootstrap analysis revealed that the mediation paths from social personal- ity through gratitude (0.01 - 0.21 CI) and hope (0.04 - 0.25 CI) to life satisfaction were significant (see Figure 1). The final step tests whether the direct association between the independ- ent and the dependent variables remains significant (indicating partial mediation) or loses significance entirely (indicating full mediation). Analysis shows that hope and gratitude fully medi- ate the association between social vocational personality and life satisfaction. When we controlled for hope and gratitude, there was no direct association between social personality and Open Access 989  H. LITTMAN-OVADIA ET AL. Table 3. Regression coefficients predicting vocational personality types from character strengths. B SE B β R R2 F ∆R2 ∆F Investigative Interests Step1 0.24 0.056*** 8.89 Age −0.11 0.04 −0.14** Gender 4.5 1.1 0.25*** Step 2 0.39 0.154*** 18.14 0.098*** 34.65 Age −0.14 0.04 −0.19*** Gender 4.5 1.0 0.25*** Love of learning 4.5 0.76 0.32*** Artistic Interests Step1 0.11 0.013 1.96 Age −0.06 0.05 −0.08 Gender −1.1 1.1 −0.06 Step 2 0.46 0.209*** 19.65 0.196*** 36.87 Age −0.08 0.04 −0.11* Gender −0.33 1.1 −0.02 Beauty 3.8 0.71 0.29*** Creativity 3.4 0.70 0.27*** Social Interests Step1 0.25 0.061*** 9.64 Age −0.15 0.03 −0.26*** Gender 0.45 0.84 0.03 Step 2 0.45 0.201*** 18.69 0.14*** 26.11 Age −0.12 0.03 −0.21*** Gender 1.5 0.80 0.10 Zest 2.8 0.64 0.24*** Spirituality 2.0 0.46 0.24*** Enterprising Interests Step1 0.14 0.019 2.93 Age −0.05 0.04 −0.07 Gender 2.4 1.0 0.15* Step 2 0.31 0.098*** 10.79 0.089*** 26.0 Age −0.06 0.04 −0.09 Gender 2.2 0.98 0.13* Creativity 3.2 0.63 0.28*** Note: N = 302. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. life satisfaction (β = 0.12, p = ns). Overall, social personality explained 23.8% of the life satisfaction variance through direct and indirect paths (F (4, 297) = 23.22, p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was fully supported. Discussion This is the first study on the relationship between Holland’s (1997) vocational personalities and the Values In Action classi- fication of character strengths (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) using an adult sample. The single previous study that offers empirical data on the relationship between Holland’s types and VIA strengths was of adolescents (using the VIA-Youth Inven- tory of Strengths) and the strengths were mainly tested at the level of the five broader strength factors. In the present study, associations were found between all six vocational personalities and 23 of the 24 character strengths. Most, but not all, of these correlations are negligible (r < 0.10) or small (r < 0.30). Realistic personality was not associated with persistence. In fact, associations between realistic and conventional personalities to character strengths yielded only negligible (r < 0.10) or small (r < 0.30) results, and these re- sults were consistent with previous findings among adolescents (Proyer et al., 2012). Proyer et al. (2012) explained that the weakest relationships with strengths were expected for real- istic and conventional personalities since interest in manual and office-related occupations seems unrelated to a person’s streng- ths expression. Investigative personality was associated with love of learning and curiosity, as hypothesized, although not with prudence. In a regression analysis, controlling for the ef- fects of age and gender, 9.8% of the variance of the investiga- tive personality was predicted by love of learning, very similar Open Access 990  H. LITTMAN-OVADIA ET AL. Figure 1. A multiple mediation model of social personality and life satisfaction through gratitude and hope. Note. Coefficients from bootstrap proce- dure are provided along the paths. Coefficients when controlling for the mediating variables are provided in parentheses. ***p < 0.001. to the overlapping variance of investigative personality and intellectual strengths found in Swiss adolescents (Proyer et al., 2012). Artistic personality was associated with creativity and beauty, as hypothesized, but also with 13 other strengths. Social personality was associated with social intelligence, kindness, love, teamwork, gratitude, hope and zest, as hypothesized, but also with six other strengths. In regression analyses, controlling for age and gender, artistic and social personalities were found to be with the highest overlapping variances with strengths (19.6% and 14%, respectively). Artistic personality was best explained by creativity and appreciation of beauty, while sur- prisingly, social personality was best explained by zest and spi- rituality. Spirituality is included in the transcendence strengths factor (e.g., hope, gratitude), which together with the other- directed factor (e.g., kindness, teamwork) was found to explain 11% of social personality variance (Proyer et al., 2012). Enter- prising personality was associated with zest, as hypothesized, but not with bravery, leadership and hope. Unexpectedly, en- terprising was associated also with creativity, love of learning and persistence. In regression analysis, controlling for age and gender, enterprising was best explained by creativity (7.9% overlapping variance). Overall, there seems to be an overlap between virtuousness and investigative, artistic, social and en- terprising personalities. Neither conventional nor realistic per- sonalities were explained by any of the strengths scales. We also found, for the first time, a positive association of Holland’s social personality with life satisfaction. Although previous studies and meta-analyses have indicated that person- ality traits are one of the best predictors of life satisfaction (e.g., Steel et al., 2008), only one study examined personality using Holland’s (1997) RIASEC conceptualization (Cotter & Fouad, 2011). Steel et al. (2008) suggested examining the impact of major personality dimensions rather than specific traits, when examining the relationship with life satisfaction. Vocational personalities, which include multiple traits, can be considered major personality dimensions. In the current study, social per- sonality was associated with 13 different strengths, all of which were also associated with life satisfaction. The moderate posi- tive association of Holland’s social personality with life satis- faction, which we found, can be indirectly supported by re- search findings suggesting associations between Holland’s social personality to extraversion and agreeableness (Barrick et al., 2003; Gottfredson et al., 1993). Higher levels of extraver- sion and agreeableness have been linked to greater life satisfac- tion (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998; Diener et al., 2003). Notable is the difference between social and artistic person- alities, which both had associations with strengths that are most strongly related to life satisfaction, but only social personality was found to have a direct relation with life satisfaction. While social and artistic personalities apparently share their variance with strengths associated with life satisfaction, an important characteristic that potentially links artistic personality to life satisfaction was not found. Social personality is associated with extraversion (Barrick et al., 2003; Gottfredson et al., 1993). Individuals high in extraversion as in social personality tend to be highly sociable, friendly and optimistic. Individuals high in artistic personality, tend to be complicated, disorderly, impul- sive, independent, introspective, intuitive, nonconforming, open, original and sensitive. These characteristics relate to openness rather than to extraversion (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Spokane & Cruza-Guet, 2005). We also found that the association between social personality and life satisfaction is fully mediated by the two most satisfied strengths: hope and gratitude. Our results suggest that the vari- ance shared by social personality and life satisfaction is medi- ated by hope and gratitude. Therefore, we suggest that indi- viduals high in social personality, who are described as being sociable, friendly and optimistic, can achieve life satisfaction by endorsing gratitude (being aware of and thankful for the good things that occur in life, taking time to express thanks) and hope (expecting the best in the future and working to achieve it, believing that a good future is something that can be brought about). In other words, the social person achieves life satisfaction through a positive view of her past, present (grati- tude), and future (hope). Theoretical and Practical Contribution and Implications The main theoretical contribution of this study is in linking Holland’s well-established vocational theory with the promis- ing VIA strengths theory and positive psychology. This link enhances both the field of vocational counseling and the field of positive psychology by offering a wider perspective on voca- tional personality and on “good character” in general. The combination of the longstanding RIASEC model and the rela- tively new VIA-IS model offers a more comprehensive founda- tion for understanding and designing interventions in the field of work and career. As postmodern vocational counseling em- phasizes the importance of change and adaptation, on both the individual and the environmental level (Savickas, 2011), adopt- ing the character strengths model allows counselors to assume that deployment of certain strengths in the workplace has the potential to generate change and contribute to life satisfaction. Additionally, adopting a more dynamic model such as the model proposed in the current study expands vocational coun- selors’ “tool box” beyond knowledge derived from traditional P-E fit models. The results shown in this study further support greater atten- tion to character strengths in career guidance, career counseling and career development. Although strengths are described as personality traits, endorsement of strengths can be actively enhanced through career guidance and counseling. A person’s life satisfaction may increase by endorsing specific strengths, as these research findings suggests. The consideration of strengths may provide incremental validity in predicting work satisfac- tion. A study of both personalities and strengths that can be conducted in a workplace setting is needed to see whether together they can better predict positive experiences in the workplace as well as life satisfaction. The limited but plausible Open Access 991  H. LITTMAN-OVADIA ET AL. overlap between strengths and vocational personalities indicates that both are not redundant domains of work personality. Limitations The study findings should be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations. First, all our variables were measured with a cross-sectional design, which requires caution in interpreting causality. Therefore, future studies should include longitudinal designs to strengthen this potential causality chain. Second, we used a snowball sampling method, which inhibits the generali- zation of our findings. Our sample included a variety of occu- pations. Although this should potentially increase generalizabil- ity, it also statistically increases unexpected confounding vari- ables that make interpretation of results difficult. Future Research This is the first study to link the Holland’s six vocational types with the VIA’s 24 strengths in adults. Future research should focus on replicating these findings in other countries and cultures. To further inspect strengths’ power to predict voca- tional personalities and life satisfaction, a longitudinal study design should be implemented in future research. A longitude- nal study design can also be of assistance when evaluating changes in strengths endorsement through career guidance and counseling, and measuring the effects of these changes on life satisfaction and career development over time. REFERENCES Anaby, D., Jarus, T., & Zumbo, B. D., (2009). Psychometric evaluation of the Hebrew language version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale. Social Indicators Research: International Interdisciplinary Journal for Quality of Life Measurement, 96, 267-274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9476-z Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K., & Gupta, R. (2003). Meta-analysis of the relationship between the five-factor model of personality and Hol- land’s occupational types. Personnel Psychology, 56, 45-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00143.x Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155-159. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155 Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO personality inventory. Psychological Assessment, 4, 5-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.5 Cotter, E. W., & Fouad, N. A. (2011). The relationship between subjec- tive well-being and vocational personality type. Journal of Career Assessment, 19, 51-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1069072710382614 DeNeve, K. M., & Copper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta analysis, of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psycho- logical Bulletin, 124, 197-229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.197 Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71-75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 Diener, E., Eunkook, M. S., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Sub- jective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276-302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276 Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 403-425. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145056 Gottfredson, G. D., Jones, E. M., & Holland, J. L. (1993). Personality and vocational interests: The relation of Holland’s six interest di- mensions to five robust dimensions of personality. Journal of Coun- seling Psychology, 40, 518-524. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.40.4.518 Harzer, C., & Ruch, W. (in press). The application of signature charac- ter strengths and positive experiences at work. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 965-983. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9364-0 Harzer, C., & Ruch, W. (2012). When the job is a calling: The role of applying one’s signature strengths at work. Journal of Positive Psy- chology, 7, 362-371. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2012.702784 Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A theory of voca- tional personalities and work environments (3rd ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. Holland, J. L., Fritzsche, B. A., & Powell, A. B. (1994). The self-di- rected search technical manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assess- ment Resources. Larson, L. M., Rottinghaus, P. J., & Borgen, F. H. (2002). Meta-ana- lyses of Big Six interests and Big Five personality factors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61, 217-239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1854 Lavy, S., & Littman-Ovadia, H. (2011). All you need is love? Strengths mediate the negative association between attachment orientations and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 0101- 0100. Littman-Ovadia, H., & Lavy, S. (2012). Character strengths in Israel: Hebrew adaptation of the VIA inventory of strengths. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28, 41-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000089 Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9, 111-131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111 Meir, E. I., & Hasson, R. (1982). Congruence between personality type and environment type as a predictor of stay in an environment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 21, 309-317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(82)90039-2 Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2008). Positive psychology and character strengths: Application to strengths-based school counseling. Profes- sional School Counseling, 12, 85-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.5330/PSC.n.2010-12.85 Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 603- 619. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/jscp.23.5.603.50748 Peterson, C., (2006). A primer in positive psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. (2005). Orientations to hap- piness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. Jour- nal of Happiness Studies, 6, 25-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E .P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879-891. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 Proyer. R. T., Sidler. N., Weber. M., & Ruch, W. (2012). A multi-method approach to studying the relationship between charac- ter strengths and vocational interests in adolescents. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 12, 141-157. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10775-012-9223-x Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). To be happy or to be self-fulfilled: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. In S. Fiske (Ed.), Annual Review of Psychology (Vol. 52). Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews Inc. Ruch, W., Proyer, R. T., Harzer, C., Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2010). Values in Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS): Adaptation and validation of the German version and the develop- Open Access 992  H. LITTMAN-OVADIA ET AL. Open Access 993 ment of a peer-rating form. Journal of Individual Differences, 31, 138-149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000022 Savickas, M. L. (2011). Career counseling. Washington DC: American Psychological Association. Spokane, A. R., & Cruza-Guet, M. C. (2005). Holland’s theory of vo- cational personalities in work environments. In S. D. Brown and R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 24-41). New York: Wiley. Steel, P., Schmidt, J., & Shultz, J. (2008). Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulle- tin, 134, 138-161. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.138

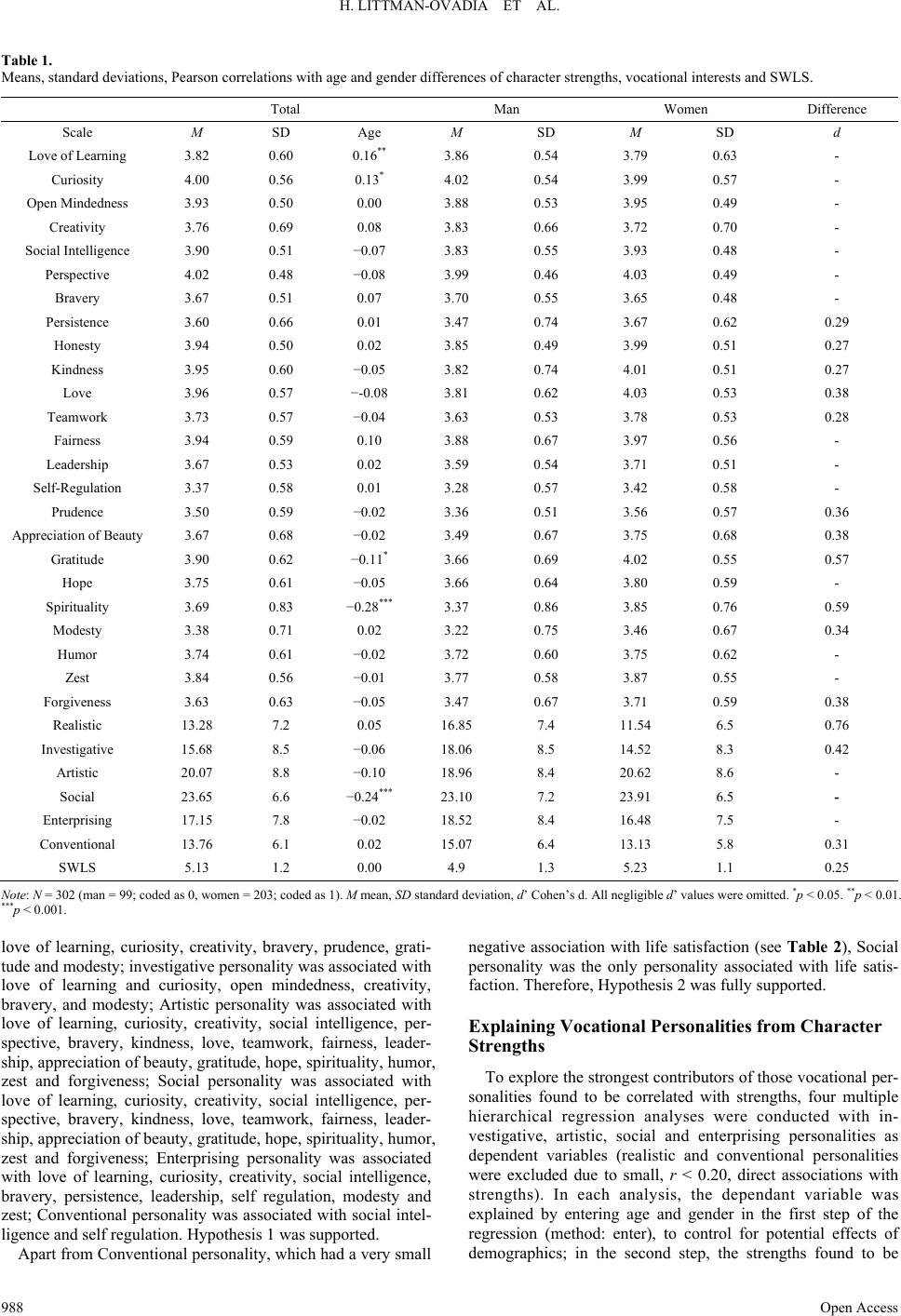

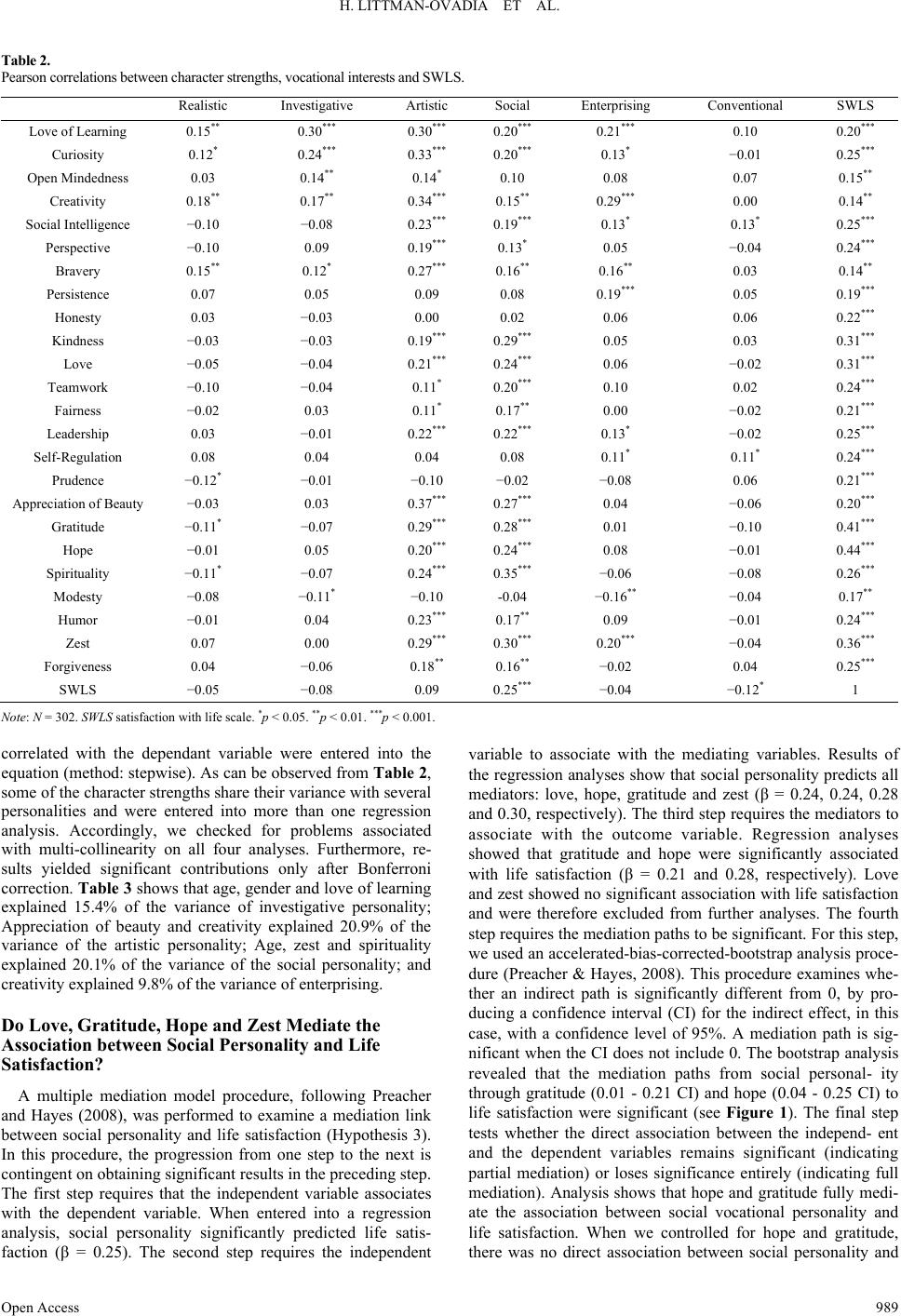

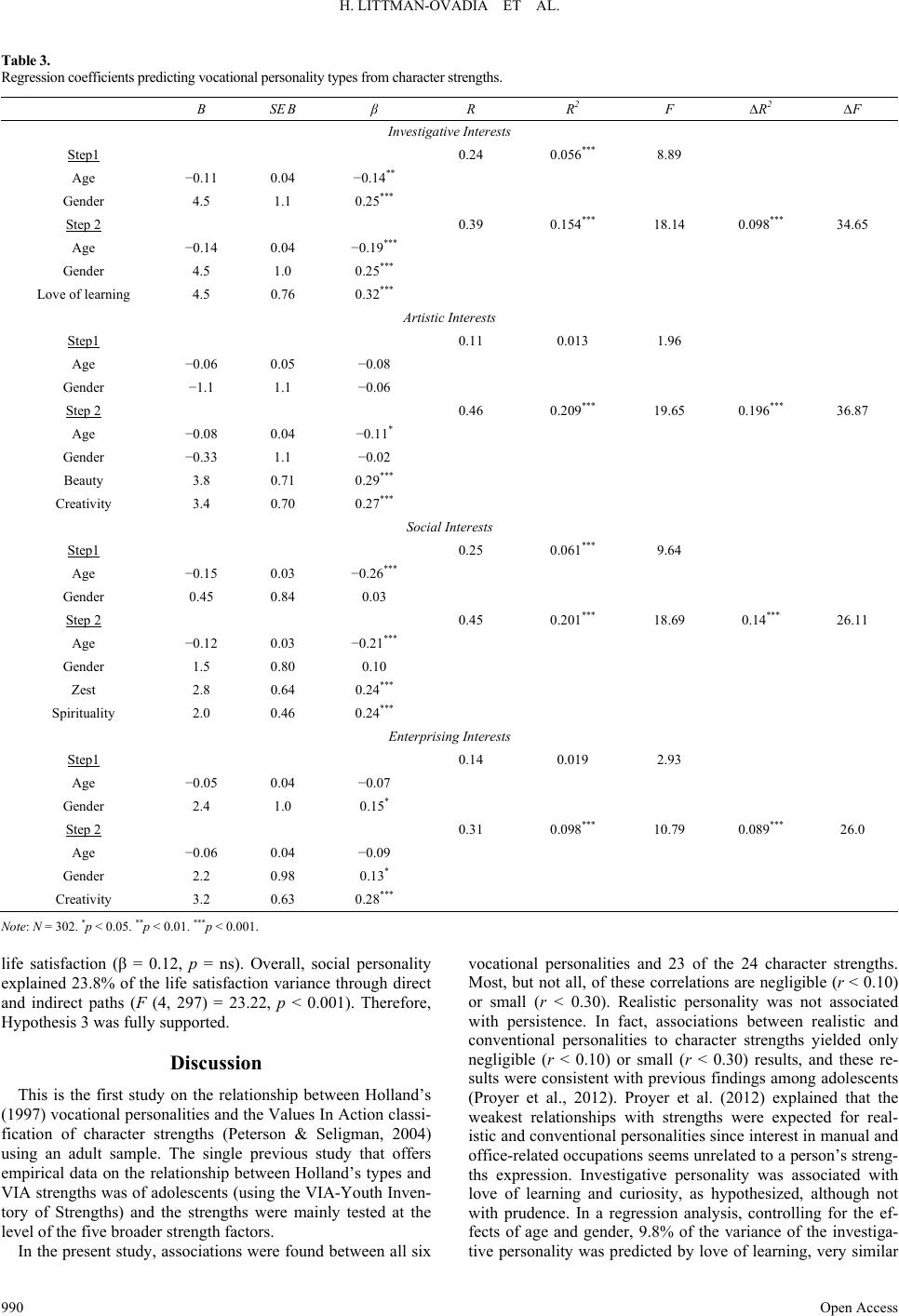

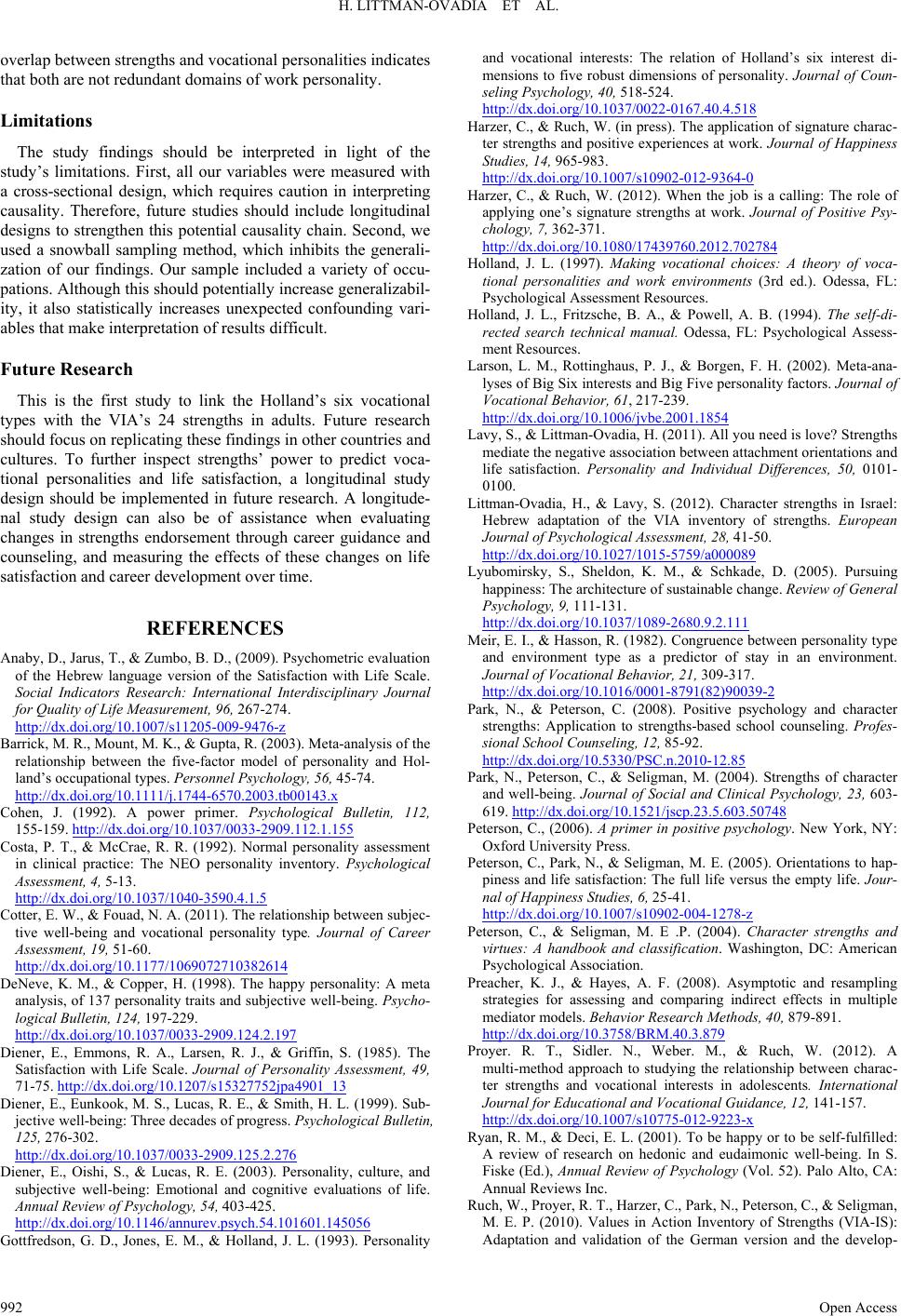

|