World Journal of AIDS, 2013, 3, 335-344 Published Online December 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/wja) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/wja.2013.34043 Open Access WJA 335 Assessing the Relationship between Caregivers Burden and Availability of Support for Family Caregivers’ of HIV/AIDS Patients in Calabar, South East Nigeria Ekaete Francis Asuquo1*, Josephine B. Etowa2, Prisca Adejumo3 1Department of Nursing Science, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria; 2School of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada; 3Department of Nursing Science, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria. Email: *ekaetefasuquo@yahoo.com Received September 16th, 2013; revised October 15th, 2013; accepted October 20th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Ekaete Francis Asuquo et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Purpose: This study examined the level of burden and the extent of support on family caregivers of people living with AIDS (PLWHA) in Calabar, South East Nigeria. Methods: A mixed method with cross sectional approach was used. Purposive sampling technique guided the recruitment process and data collection methods included, semi-structured questionnaires and focusing group discussion. 260 respondents participated in the study. The quantitative data were mined with the aid of SPSS and the qualitative data were analysed with the aid of NVivo8 using thematic analysis. Re- sults: Results indicated high level of burden with limited support to caregivers. A Chi-square value of 25.1 was ob- tained at P < 0.05, suggesting a significant relationship between availability of support and caregivers burden. This rela- tionship was supported by the themes of physical, social, emotional and financial burden for the caregivers. Similarly, information on coping skills, emotional support, financial assistance and help with caregiving themes emerged for so- cial support. Conclusion: In Nigeria, the burden of caring for HIV/AIDS patients has a remarkable impact on family caregivers. This calls for the development of policies that can systematically address the needs of family caregivers in order to ameliorate the negative consequences of caregiving for PLWHA. Keywords: Family Caregivers; Caregivers’ Burden; Caregivers’ Support; People Living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA); Nigeria 1. Introduction Providing care for a sick family member is a normative role embedded in African culture. It is an age-long tradi- tion of kindness, love and loyalty, which binds family members together [1,2]. Family members therefore be- come the principal source of informal long-term care to an ill or disabled family member [3,4]. Culturally in Af- rica, the criteria for selecting primary caregivers are linked to sex, generation and geography [4] and near kinsman or close relation from the nuclear family. These roles are assumed without questioning and may be laden with adverse consequences [5-7]. HIV epidemic has be- come a major public health challenge of our times and its impact engulfs all sectors of our life including homes [8-11]. Global effort has been directed to tackle this pan- demic and to reduce its prevalence in which it is no longer a public health issue. While this effort has led to advancement in medicaltreatment and improvement in life expectancy, increasing numbers of people are living with chronic illness and disabilities. And this has a det- rimental effect on family members who assume caregiv- ing role and bore the brunt of taking care of those with chronic conditions including the HIV epidemic. This is particularly problematic in sub-Saharan Africa where they are 22 million cases (69%) [12]. A synergistic rela- tionship exists between high prevalence of HIV and the demand for health care services and also has a burden on both formal and informal caregivers [13]. Hence HIV’s burden transcends the health care system to families and friends who are without appropriate sensitization and educational preparation to take up the caregiving role to meet the health need of their family members [5,6,14-16]. *Corresponding author.  Assessing the Relationship between Caregivers Burden and Availability of Support for Family Caregivers’ of HIV/AIDS Patients in Calabar, South East Nigeria 336 This is a significant contribution by the informal care- givers who form the backbone of health care system round the world [17,18]. Most often, they remain hidden and their contribution to care receivers is unrecognized. Studies revealed that caregivers experience negative physiological, psychological, behavioral as well as fi- nancial consequences of caregiving [5,6]. Burden of Care The Nigerian health care system is based on the implicit assumption that, family members are available to provide care in the homes to the dependent ill, the elderly, physi- cally and mentally disabled member. Previous report in- dicates that caregivers are increasingly being required to perform complex tasks similar to those carried out by paid health or social service providers [3]. Therefore the extent of care provided by these care givers covers mini- mal assistance with activities of daily living to complete care of a debilitated patient. These care are complicated with the chronic pattern of exacerbation and remission associated with HIV/AIDS, which depends on the care- givers appraisal of the experience that may produce high level of burden [15,19,20]. Caregiving stress model iden- tified the stress process including the background, stress- ors, mediators and outcome [21]. Agreeing with these assertions, other authors [22,23] declared that factors which influence burden include the characteristics of caregiving context such as duration of care, extent of social support and quality of family relationship, charac- teristic of the caregiver and characteristic of the care re- ceiver. This perceived stress was identified as caregiver’s burden [24] in reference to inconvenience associated with caring for mentally ill relatives and later conceptu- alized as the degree to which the emotional, physical health, social life, and financial status of a caregiver has been impaired as a result of caregiving [25]. This con- ceptualization is used in this study as the degree to which life’s tension is expressed to depict the physical, emo- tional, financial and social challenges associated with caring for PLWHA. The high level of burden experienced by the caregivers may notably have produced negative consequences which are manifested as symptoms of anxiety and de- pression and induced changes that could lead to heart disease, hypertension, psychological worries, loneliness, increasing rate of physiological illness and suppressed immune responses. Others include reduced engagement in preventive health behaviors, social problems, etc. [4,5,15,16,26,27]. It is important to note that the task of caregiving is not only stressful to the family care giver, and it has a serious impact on the patient quality of life. A correlation has been found existing between the level of burden and quality of life of the care receiver [5,7]. 2. Support to Caregivers The pattern of HIV occurrence has been classifiedinto four phases namely onset, course, outcome and degree of incapacitation [28]. Utilizing this typology, HIV has a gradual onset with a long term stress on the patient, the course is progressive with symptoms which increases in severity. As disabilities become progressive with less periods of relief, the patients and caregivers are rendered psychologically, socially and physically disabled [28,29]. The level of burden experienced by caregivers differ de- pending on degree of incapacitation of the recipient [28,30]. The need to support caregivers of PLWHA for contin- ual adaptation to task changes become imperative since the perceived goal is to reduce burden of care on care- givers. The conceptualization of social support is viewed as coping assistance or the active involvement of signifi- cant others in the caregivers ability to manage stress [31]. This is the concept utilized in this study. The significant others may be family, community members or friends, and occasionally professional institutions’ help may be required from time to time [28]. The help rendered by significant others enhances coping ability as it satisfied the need for attachment, relieves stress, and boosts a sense of self-worth, trust and life-direction [32-34]. The burden associated with caring for PLWHA differs from caring for someone with cancer or other debilitating dis- eases, since HIV involves social isolation, contagion and stigmatization, hence caregivers are emotionally laden with high level of burden. Adequate support is needed to encourage and prepare caregivers to express hurt, anger and fear before taking up caregiving role. Burden of care can be ameliorated by factors such as support from other family members, the ability to use problem-focused cop- ing strategies and availability of support from the com- munity [32]. Other factors include the provision of in- formation and advice, participation in social activities and help from caregiving and emotional support [35-37]. Provision of information for coping with stress and deal- ing with emotions are important areas where caregivers may require help [33,38,39]. On the other hand burden can be worsened when the people involved are socially isolated, less knowledgeable about the condition or have limited interpersonal skills. This study therefore assesses the burden of caregivers, availability of support and proffers the appropriate intervention measures as a pana- cea for delivering efficient quality care to the patients and wellbeing of caregivers. 3. Materials and Methods Location of the Study The study was carried out in Calabar Municipality of Open Access WJA  Assessing the Relationship between Caregivers Burden and Availability of Support for Family Caregivers’ of HIV/AIDS Patients in Calabar, South East Nigeria 337 Cross River State of Nigeria. Calabar is located at the extreme end of southern eastern Nigeria between latitude 4˚58′ North and longitude 8˚17′ East. Calabar Municipal- ity host the University of Calabar Teaching Hospitals (a tertiary institution) which acts as referral center to pri- mary and secondary health care facilities in the state. It has been selected by the Federal Government of Nigeria as one of the centres for the management of people living with HIV/AIDS. The study was informed by the high HIV prevalence of 10.4% [40] at the study site. 4. Methods Study participants constituted a convenient sample of 260 caregivers who were primary caregivers to PLWHA between June and December 2009. Participants were identified through HIV clinic of the University of Cala- bar Teaching Hospital and visitation list of a voluntary caregiver of PLWHA, an NGO (Positive Development Foundation, Calabar, Nigeria). Inclusive criteria were: being a caregiver for more than one month and also car- ing for PLWHA patient with some functional abilities as a family member. A total of 299 potential caregivers met the inclusive criteria of being primary caregivers, but only 260 completely filled their questionnaires, 11 care- givers did not know the diagnosis of ailment of their care receivers. Twelve (12) refused to participate while 16 did not complete their questionnaires. Two sessions of focus group discussions were also used to encourage self-dis- closure among the participants [41] and to complement findings from the questionnaires. Being a primary care- giver involved participants who provided unpaid physical support such as helping in activities of daily living, shopping, food preparation, helping in administering me- dication, overseeing medical appointment, financial, and emotional support to PLWHA. The study was submitted to the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital Ethics and Research Committee, who gave the approval for con- ducting the study. Consent was also obtained from the Managing Director of Positive Development Foundation. Informed consent was also obtained from study partici- pants following full description of the aims and objec- tives of study. Caregivers Burden. The Zarit Burden Interview scale questionnaire, semi structured questionnaire on social support and focus group discussion were the main in- strument for data collection. Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) scale made up of 22 items was used to measure the level of burden. This scale reflects the degree of emotional, physical health and social impact of caregiving on care- givers while caring for PLWHA [42]. The respondents indicated the discomfort they experienced of particular items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 - 4. The total score ranged from 0 to 88 and a high score corre- lated with higher level of burden. The psychometric properties of Zarit Burden Interview scale had been ex- amined in many studies with an estimated internal con- sistency reliability of Chronbach’s alpha ranges of 0.88 to 0.92 [43]. The social support questionnaire consisted of 12 items on a 4-point Likert scale assessing the avail- ability of support on Information, financial help, help with caregiving and emotional support available to care- givers’. The questionnaire was translated into Efik (the native language of the people) and back-translated into English by experts to ensure that there was no lost of meaning. The Efik version was administered to caregiv- ers with little or no education. The NGO (Positive De- velopment Foundation) provided the forum for three fo- cus group discussions with about 8 to 10 participants at each session. A total of 27 caregivers participated in the focus group discussion after having completed the ZBI and social support questionnaire. Focus group discussion as an assessment tool involves an organised discussion with a selected group of individuals to gain information about their views and experiences on a topic [44]. It has the advantage of creating greater room for spontaneity and participants feel supported and empowered within the acuity of the group and its cohesiveness [45]. Data Analysis Data collected were analyzed using the Statistical Pack- age for the Social Sciences (SPSS 16.0) software to gen- erate the frequency and percentages of the values. By the application of inferential statistics (Chi-Square test), the level of significance was also determined at the P-value of 0.05. For level of burden, scores ranged from 0 to 88. Zero to twenty (0 - 20) represented little or no burden, 21 - 40, mild to moderate burden; 41 - 60, moderate to se- vere burden and 61 - 88, severe burden [46]. Thematic analysis was used for assessing the focus group discus- sion sessions [47]. Sixty five (65) codes emerged which were developed into 4 basic themes namely physical, social, emotional and financial burden, which provided impetus for understanding the level of burden experi- enced by the caregivers. Four basic themes namely pro- viding information on practical and coping skills, finan- cial assistance, help with caregiving and emotional sup- port emerged as caregivers support needs. 5. Results In this study, the demographic variables and level of caregivers burden are presented as frequency, percent- ages and ranges. Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. The majority of the respondents were females 199 (76.5%) while 61 (23.5%) respondents were males who voluntarily took up the care Open Access WJA  Assessing the Relationship between Caregivers Burden and Availability of Support for Family Caregivers’ of HIV/AIDS Patients in Calabar, South East Nigeria 338 Table 1. The Socio-demographic data of respondents (N = 260) in Calabar Municipality, Nigeria. Variables Frequency Percentage (%) Sex Male 61 23.5 Female 199 76.5 Age (yrs) 10 - 20 22 8.5 21 - 30 30 11.5 31 - 40 51 19.6 41 - 50 90 34.6 51 and above 67 25.8 Educational Qualification Primary 15 5.8 Secondary 112 43.1 Tertiary 111 42.7 Never been to school 22 8.5 Household Income Level US$*/Day Less than $6.00 130 50.0 $7.00 - 8.00 59 22.7 $9.00 - 10.00 25 9.6 $11.00 - 12.00 18 6.9 $13.00 - 14.00 13 5.0 $14.00 and above 15 5.8 Number of People in the Household 1 - 3 19 7.3 3 - 6 153 58.9 7 and above 88 33.8 Duration (Hrs/day) 3 - 8 Hrs/day 52 20 9 - 12 Hrs/day 162 62.3 13 - 24 Hrs/day 46 17.7 Duration (Yrs) Less than 1 year 101 38.9 Between 1 - 2 years 109 41.9 Between 2 - 3 years 38 14.6 Above 3 years 12 4.6 *1 US$ = N 164.00 (Nigerian Naira). giving roles. Majority respondents, 90 persons (34.6%) were in the age class of 41 - 50 years. This age class was closely followed by 51 years and above comprising of 67 indi- viduals (25.8%) and the teenage class of 10 - 20 years of 22 (8.5%) respondents. The highest educational qualifi- cation attained by most respondents was secondary edu- cation with 112 (43.1%) respondents followed by 111 (42.7%) respondents with tertiary education. Other char- acteristics of the caregivers are as shown in Table 1. 6. Level of Burden on Caregiving Generally, the results revealed a level of burden ranging from 14 - 71 on ZBI Scale (Table 2). 49 (18.8%) ex- perienced no burden while providing care, 67 (25.8%) respondents experienced mild to moderate level of bur- den, 93 (35.8%) experienced moderate to severe level of burden while 51 (19.6%) respondents experienced severe level of burden in providing care to PLWHA. Focus Group: The extent of burden expressed fol- lowing discharge from health care institution was catego- rized into four basic themes namely physical, social, emotional and financial burden. Carers generally per- ceived caring for PLWHA to be very stressful as they reported that their tasks ranged from simple to complex and covering all the “activities of daily living” such as putting care recipient to bed and getting up, bathing, dressing, toileting and coping with incontinence wors- ened during period of exacerbation, preparing food, giv- ing medications, providing financial assistance, and emo- tional support like keeping company especially when care recipient is depressed. These activities left them with aches and pains, and fatigue and exhaustion were regular experiences in their life. Physical Burden: Caregivers generally express that they experience extreme fatigue as they indulge in day to day caregiving. Caregiving to them is very challenging and produces ill effect on their physical health. The physical ill effect of caregiving as perceived by the care givers include fatigue and exhaustion “you keep doing one task to another and no rest period, even some nights Table 2. The distribution of caregivers burden on Zarit Burden Interview scale (ZBI). Level of Burdens n = 210 % Range No Burden 49 18.8 0 - 21 Mild to Moderate Burden67 25.8 21 - 40 Moderate to Severe 93 35.8 41 - 60 Severe Burden 51 19.6 61 - 88 Total 260 100 0 - 88 Open Access WJA  Assessing the Relationship between Caregivers Burden and Availability of Support for Family Caregivers’ of HIV/AIDS Patients in Calabar, South East Nigeria 339 become day because it is pack filled with activities”. Some expressed the feeling of being trap to responsibility, “I just can’t ignore him as other members of our house- hold do, it becomes my responsibility and mine alone as the wife”. The stress experienced enhances discourage- ment and helplessness. Reports of physical ailments such as continuous waist pain, “I have been lifting him for bathing, but as the waist pain persist if no help is avail- able I bath him in bed”. Other physical effects include, weight loss, headaches and many lack the energy to face another day. With reference to their perceived health status, the discussants generally agreed that their health had suffered as noted “I used to be plum, but since I started caring for her, I’ve lost weight and I don’t have sufficient time to care for myself, and some friends ask me, are you sick? I really know that this work has af- fected me.” Another reported that she is now diagnosed of having hypertension which she attributed to excessive worries due to caregiving. Most discussants revealed that burden of care increases during period of exacerbation. One said “I suffer most when he has diarrhea, the wrap- pers (native African wear around the waist down to the knee) are not enough, you keep washing and reusing, he is weak and frail, I am caring for him and many other things I have to do to make ends meet. At the end of the day I feel drained, tired and worn out”. Some narrated that burden also increased when the care receiver exhib- ited some abnormal behavioral symptoms, a situation which demanded continuous supervision coupled with providing care. “I can cope with bathing and feeding or anything else but when he starts talking to air, becoming very suspicious of everybody and acting abnormal, I feared for my life and that of others in the house”. Emotional Burden: During the FGD sessions, parti- cipants raised some issues which impacted them emo- tionally such as being unduly irritable, fear of the un- known, guilt and fear of being susceptible to HIV through caregiving. Most of the discussants revealed that the burden has influence their emotional wellbeing as they become unduly irritable and used aggressive words when provoked, which were later regretted. This was portrayed by the words of a female caregiver who said “I slapped my child who insisted that I should be at the school’s parent teachers association, there was no rea- son for that for God sake no reason. I felt disappointed by my action and I started crying”. Another reported, “I woke up some days feeling depressed and afraid of what the day holds, and on such days, tears flow freely from my eyes”. Another reported, “sometimes I get annoyed and upset when others are laughing, and I often won- dered what is good about life that thrills their heart”. Fear of the unknown has been a serious trait to caregivers, as most of them harbor anticipatory grief about the im- minent death of their sick relative especially knowing that HIV has no cure. This fear is common especially when the care receiver is a bread winner. A woman said “when my husband is dead (sick relative) and the pension stop coming in, what will become of the family”. Some felt already susceptible to HIV through caregiving and some felt stigmatized as HIV positive. Caregivers were generally committed to the care of their relatives with some strong emotional ties which would produce guilt if they should leave the caregiving role, “We’ve been mar- ried for 30 years although the last eight years was noth- ing to write home about, but he is my husband anyhow” another added “he is my only son I will always love and care for him”. Social Burden: Social groups provide companionship, support and a feeling of togetherness which has a posi- tive effect on caregivers’ health and well-being. Some discussants feel isolated from their social group due to lack of time for such functions or due to poor self- esteem. Some reported reduced time spent on self, spouse and children. A discussant reported feeling un- comfortable especially when they had a known visitor. “I just felt they may be thinking I am also HIV positive”. Another retorted, “It’s like falling from grace to grass, and your self esteem is gone”. Another remarked “Myboy friend called it quit when he found out I was caring for my brother who had HIV”. Some wished they could leave the caregiving role to someone else, one caregiver complained “but who do you leave it to”. Financial Burden: The financial burden of caregiving is a significant aspect that worsens caregiving experience especially in low and middle income countries such as study setting where most individuals live below one dol- lar per day [47]. Most carers revealed that this aspect is an issue as it influences the administration of drugs and other activities such as school fees for children and gen- eral family upkeep. Sometimes children drop out of school taking to hawking as a way out. Even with those who chose hawking as a remedy, discrimination and stigmatization takes its toll on their ability to sell their farm products where they are known. A discussant nar- rated “my children started hawking to make ends meet because I couldn’t pay for their secondary education any more”. Another said, “I had to hawk my farm products away from home because neighbors won’t buy from us”. Another discussant reported, “We sometimes suspend giving drugs until when food is available, since he can- not take drugs with empty stomach. Although we are aware that this is not right but what can we do when there is no money to buy the food”. Generally, they agreed that lack of money was a serious constraint to caregiving although some agreed to some level of finan- cial support from Church and NGOs. Open Access WJA  Assessing the Relationship between Caregivers Burden and Availability of Support for Family Caregivers’ of HIV/AIDS Patients in Calabar, South East Nigeria Open Access WJA 340 6.1. Availability of Support to Caregivers 6.2. Financial Assistance The availability of support was categorized into four sec- tions namely: providing information on practical and co- ping skills, financial assistance, help with caregiving and emotional support (Figure 1). Among the 260 respon- dents, 152 (58.5%) agreed to have received some form of support while 108 (41.5%) received no form of support at all. The form of support received include: 6 (0.2%) information on practical and coping skills, 36 (13.9%) financial assistance, 72 (27.7%) help with caregiving and 38 (14.6%) emotional support. Most caregivers perceived their role to be extremely stressful with adverse conse- quences on their health, which some form of support from individuals or government could have helped to ameliorate. All caregivers unanimously express the need for financial support as recipient disease condition had impinged on the family resources. Even caregivers who had some form of financial support felt it was not enough. A care- giver expressed “not just giving money from time to time, I wish the governmentcan employ one of my children, it will help make life easy for us”. Coping strategies varied among the caregivers which included children dropping out of school to hawking, begging and other subservient means of survival as a way out. Help with Caregiving: Most care givers expressed that they needed a break occasionally from providing care and a relief period would have cushioned the effects from both physical and mental stress of caregiving. It would also foster social relationship and alleviate feel- ings of isolation. “I know if I had the time I would be going to church more often and something would have been said to help me. But it seems this work is my sole responsibility, no time for what I want to do for myself”. Providing Information on Practical and Coping Skills: Majority of discussants revealed that they had no prior information from hospital staff on how to care for recipients. Their knowledge and skills on care came from trial and error and past experiences based on previous life situations. Many wished they had training to assure themselves they were providing the right care “I wish I was trained, nevertheless I just do all I can for him, if this did not work, I try something else”. The caregivers generally wished they had training to assist them in deci- sion making and problem solving relating to their roles. The fear of stigmatization also prevented some from seeking advice from some support staff. The forum pro- voked negative feeling when some learnt about the foundation that supported PLWHA and available ser- vices. Although the foundation had their own challenges such as number of people that volunteered to provide care for PLWHA, information regarding recipient health conditions and their implications coupled with how to prevent contagion through caregiving was also identified as areas that required attention. Emotional Support: Throughout the focus group ses- sions, group members expressed anticipatory grief about the sad end of their stressful endeavor. Always probing to know if early death was still inevitable with drugs. Fear of susceptibility to HIV was also raised which com- pounded caregiving role. The need for counseling ser- vices was identified to help in eradicating fear and anxi- ety associated with caregiving. The relationship between availability of support and caregivers’ burden was also evaluated. Out of 152 re- spondents that had received some form of support, 37 experienced no burden, 44 respondents experienced mild to moderate burden, the majority, 56 respondents ex- perienced moderate to severe burden while 15 respon- dents experienced severe burden (Table 3). Out of 108 respondents that received no support, 12 Information on Practical skills Financial Assistance Assistance with Caregiving Emotional Support o form of Support 6 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 No. of Respondents 36 38 72 108 Figure 1. Bar chart showing the extent of support to caregivers of PLWHA in Nigeria.  Assessing the Relationship between Caregivers Burden and Availability of Support for Family Caregivers’ of HIV/AIDS Patients in Calabar, South East Nigeria 341 Table 3. The relationship between availability of support and caregiver s’ bur den. Availability of Support No Burden Mild to Moderate BurdenModerate to Severe BurdenSevere Burden Total Received any form of support 37 (28.7) 44 (39.2) 56 (54.4) 15 (29.8) 152 Received no support 12 (20.4) 23 (27.8) 37 (38.6) 36 (21.2) 108 Total 49 67 93 51 260 Figures in brackets are expected frequencies. X2 Cal. = 25.1. X2 Tab. = 7.81, DF = 3, N = 260, P > 0.05. experienced no burden, 23 respondents experienced mild to moderate burden, the majority 37 respondents experi- enced moderate to severe burden while 36 respondents experienced severe burden. A Chi-square value of 25.1 was obtained at P < 0.05, which showed a significant relationship between availability of support and caregiv- ers burden (Tabl e 3). 7. Discussion The improvement in technology and the discovery of anti-retroviral drugs (medical innovations) have in- creased the longevity of PLWHA and turned HIV into a chronic ailment, which has apparently increased the bur- den of home caregivers. Many caregivers expressed dis- tress about the consequences of caregiving on their gen- eral health as revealed in this study. Majority of the care- giver’s experienced moderate to severe level of burden which suggests partial or complete reliance of most care receivers (PLWHA) on the caregivers for their physical, financial, emotional and social support especially during periods of exacerbation of HIV symptoms. This observa- tion is similar to previous report [28] who asserted that HIV has a gradual onset with a long term stress on the patient, the course is progressive with symptoms which increases in severity, and as disabilities become progres- sive with less periods of relief, it renders the patient and caregivers psychologically, socially and physically dis- abled. Therefore the level of dependency is related to the functional abilities of the care recipient. The lower the functional abilities the higher the level of burden per- ceived by the caregiver. This also corroborates with the findings by others in different locations [5-7]. Further study [48] revealed that informal caregivers experienced a lot of stress while caring for recipient and remains a valuable asset to the recipient for their quality of life. Major caregiving problem emanate from carers ability to cope with the increased needs of the care re- ceiver as a result of physical and/or mental illness [49]. Although this finding was contrary to the situation in Canada [50], PLWHA relied more on similarly disad- vantaged peers and formal caregivers for support hence there was no increased level of burden on family mem- bers. The differences in this study could also be attrib- uted to cultural expectations especially in Africa, where the provision of care for a sick family member is an age- old act of kindness, love and loyalty [1] which bind fam- ily members together in most African societies. The high prevalence of HIV in sub-Saharan African has depleted financial resources of many who cannot afford funds for health care [51]. This study revealed that the majority of the caregivers daily earning was low (Ta- ble 1), in conformity with previous observation by WHO [52]. Though this study did not assess the correlation between burden and quality of care, it is important to know that the quality of life of the care recipient depends on the quality of care provided, and the high level of burden has a detrimental effect on the caregiver and a direct effect on quality of care receiver [5,8]. The demographic characteristics of caregivers were also significant in this study as it portrayed the cultural norms of the African society such as women’s role being associated with primary caregiving in the society. Similar finding [26] revealed that within the complex system of long-term care, women’s caregiving is essential in pro- viding a backbone of support to the debilitated patient. In relation to HIV scourge, United Nations study [13] re- vealed that women are significantly affected as care re- sponsibilities fall to older and married women since a substantial proportion of PLWHA move back to their communities of origin at some stage of the illness to be cared for by family members. Also significant to the study were the age groups 41 to 50 years that form the majority that participated in care- giving. It would imply that majority of caregivers are wives, mothers, grand-mothers. Previous report [26] in- dicated that the average caregiver is 46 years old female, married and working outside the home. Majority of care- givers lived in large households with minimal household income, coupled with high financial costs of caregiving. These households face the possibility of moving further into indigence [53]. This study revealed that most caregivers received lim- ited or no support from family members, community or government and they expressed need for support. Care- givers took up the caregiving role without educational preparation. They were in most cases unfamiliar with the type of care they must provide or the extent of care needed. Knowledge on how to assess community re- Open Access WJA  Assessing the Relationship between Caregivers Burden and Availability of Support for Family Caregivers’ of HIV/AIDS Patients in Calabar, South East Nigeria 342 sources was limited. This could be due to failure by the health care workers to assess informal primary caregivers skills before assumption of caregiving role or they were just silent on the continuity of care at home which they were afraid to initiate a follow-up. In most cases, the caregivers are unprepared to provide care, due to inade- quate knowledge of health care delivery since they re- ceived limited guidance from the formal health care pro- viders [54,55]. It has been suggested that caregivers re- quire some form of training to effectively provide care and that it is unfair to presume that carers have the nec- essary knowledge and skills to care for an ill relative without some form of support [56-58]. Therefore pro- viding information and training prior to care recipient discharge would ensure caregiver’s preparedness for caring role. During the study, the need for emotional support was also identified which could be provided through health care providers linking caregivers to existing support sys- tem available in the community. Such an assistance could minimize the pressure and burden on carers since reports indicate that caregivers experienced mixture of conflict- ing emotions such as commitment, frustration, anger, loneliness, exhaustion and depression, guilt, anxiety, love and warmth which could have negative consequences on the care giver [39,57]. They further revealed that helping the care giver to acknowledge and reconcile with these emotions can enhanced coping with the challenges of being a carer. Financial assistance was also identified as area care- givers needed support. The scourge of HIV is greater among the low socioeconomic class and tends to sap the meager family resources thereby producing a higher level of burden. Caregiving is time consuming therefore care- givers who provide substantial amounts of care divert their time from other productive chores resulting in fi- nancial hardship. This is a common feature in low and middle income countries like Nigeria where many live below one dollar per day. Attempt to balance caregiving with other activities, such as work produced negative consequences and more stress on carer. Report indicated that homes engulfed in poverty and are burdened with financial costs of caregiving may move further into indi- gence [13]. Such households with a sick family members face the opposing pressures to work fewer hours and spend more time caring. Assistance with physical care such as in activities of daily living is identified as area of need in this study. It is apparent that most caregivers reach a point when they realized that housekeeping routines and regular errands were accomplished with great difficulty or left undone. It has been suggested that assistance in activities of daily living is also needed to alleviate the burden of care [13] and such help should come from other members of the family, individuals with the sameculturally background (community support) or those with similar experience such as HIV support [31]. 8. Conclusions and Recommendation In Nigeria, with 2.98 million people infected with HIV, many people will be needed to function as caregivers even though caregiving is not without consequences. This study revealed that caregivers experienced high level of burden (physical, emotional, social and financial) as a result of the care they rendered to PLWHA. There- fore there is a need to relieve this burden by providing necessary support in order to enhance the quality of care of the patients as well as maintain the optimum well-being of the caregiver. There should be training and re-training of caregivers on coping and management strategies be- fore they assume the caregiving role for PLWHA. The development of policies that can systematically assess the caregivers’ need should be promulgated. Coun- seling sessions should be organized by government and voluntary organizations regularly to present a forum where caregivers could air their problems and challenges encountered during caregiving services. Government should encourage the formation of HIV community sup- port groups to provide support to caregivers. REFERENCES [1] M. Smith and J. Segal, “Caregiving Support and Help,” 2013. http://www.helpguide.org/elder/caring_for_caregivers.ht m#family [2] L. Burton, “Age Norms, the Timing of Family Role Tran- sitions, and Intergenerational Caregiving among Aging African American Women,” The Gerontologist, Vol. 36, No. 2, 1996, pp. 199-208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/36.2.199 [3] R. Schulz and L. Martire, “Family Caregiving of Persons with Dementia Prevalence, Health Effects, and Support Strategies,” American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, Vol. 12, No. 3, 2004, p. 3. [4] R. Montgomery, J. Rowe and K. Kosloski, “Book Chap- ter: Family Caregiving,” In: C. J. A. Blackburn and C. N. Dulmus, Eds., Handbook of Gerontology: Evidence- Based Approaches to Theory, Practice and Policy, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2007. [5] National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) and AARP, “Care- giving in the US,” 2009. http://www.caregiving.org/data/04finalreport.pdf [6] F. Abasiubong, E. Bassey, O. Ogunsemi and J. Udobang, “Assessing the Psychological Well-Being of Caregivers of People Living with HIV/AIDS in Niger Delta Region, Nigeria,” AIDS Care, Vol. 23, No. 4, 2011, pp. 494-500. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2010.516340 Open Access WJA  Assessing the Relationship between Caregivers Burden and Availability of Support for Family Caregivers’ of HIV/AIDS Patients in Calabar, South East Nigeria 343 [7] M. E. Kurtz, J. C. Kurtz, C. W. Given and B. A. Given, “A Randomized, Controlled Trial of a Patient/Caregiver Symptom Control Intervention: Effects on Depressive Symptomatology of Caregivers of Cancer Patients,” Jour- nal of Pain and Symptom Management, Vol. 30, No. 2, 2005, pp. 112-122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.02.008 [8] E. F. Asuquo, P. Adejumo, J. Etowa and A. Adejumo, “Fear of HIV Susceptibility Influencing Burden of Care Among Nurses in South-East Nigeria,” World Journal of AIDS, Vol. 3, No. 3, 2013, pp. 231-238. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/wja.2013.33031 [9] A. Larson, P. Fox, S. Rosen, M. Bii, C. Sigei, D. Shaffer, F. Sawe, M. Wasunna and L. Simon, “Early Effects of Antiretroviral Therapy on Work Performance: Prelimi- nary Results from a Cohort Study of Kenyan Agricultural Workers,” AIDS, Vol. 22, No. 3, 2008, pp. 421-425. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f3cc0c [10] USAIDS, “Impact on Society,” 2013. http://sciencenow.unaids.org/2008/06/23/impact-on-socie ty/ [11] WHO, “More Developing Countries Show Universal Access to HIV/AIDS Services Is Possible,” News Release, 2010. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2010/hiv_ universal_access_20100928/en/index.html [12] UNAIDS, “Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic,” 2012. [13] “(UNAIDS) Caregiving in the Context of HIV/AIDS,” Joint United Nations Programme on 2012 HIV/AIDS, 2008. http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/egm/equalsharing/E GM-ESOR-2008-BP.4%20UNAIDS_Expert%20Panel_P aper_%20Final.pdf [14] J. Bock, “Grandmothers’ Productivity and the HIV/AIDS Pandemic in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Journal of Cross- Cultural Gerontology, Vol. 23, No. 2, 2008, pp. 131-145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10823-007-9054-2 [15] M. Bevans and E. Sternberg, “Caregiving Burden, Stress, and Health Effects among Family Caregivers of Adult Cancer Patients,” JAMA, Vol. 307, No. 4, 2012, pp. 398- 403. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.29 [16] J. Robison, R. Fortinsky, A. Kleppinger, N. Shugrue and M. Porter, “A Broader View of Family Caregiving: Ef- fects of Caregiving and Caregiver Conditions on Depres- sive Symptoms, Health, Work, and Social Isolation,” Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, Vol. 64B, No. 6, 2009, pp. 788-798. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbp015 [17] L. Feinberg, S. Newman, L. Gray and K. Kolb, “The State of the States in Family Caregiver Support: A 50 State Study,” Family Caregiver Alliance, San Francisco, 2004. [18] J. Wolff and J. Kasper, “Caregivers of Frail Elders: Up- dating a National Profile,” Gerontologist, Vol. 46, No. 3, 2006, pp. 344-356. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/46.3.344 [19] Y. Kim, R. Schulz and C. S. Carver, “Benefit-Finding in the Cancer Caregiving,” Psychosomatic Medicine, Vol. 69, No. 3, 2007, pp. 283-291. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180417cf4 [20] U. Stenberg, C. M. Ruland and C. Miaskowski, “Review of the Literature on the Effects of Caring for a Patient with Cancer,” Psycho-Oncology, Vol. 19, No. 10, 2010, pp. 1013-1025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.1670 [21] L. I. Pearlin, J. T. Mullan, S. Semple and M. M. Skaff, “Caregiving and the Stress Process: An Overview of Con- cepts and Their Measures,” The Gerontologist, Vol. 30, No. 5, 1990, pp. 583-594. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/30.5.583 [22] L. Etters, D. Goodall and B. E. Harrison, “Caregiver Bur- den among Dementia Patient Caregivers: A Review of the Literature,” Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioner, Vol. 20, No. 8, 2008, pp. 423-428. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00342.x [23] P. Werner, M. Mittelman, D. Goldstein and J. Heinik, “Family Stigma and Caregiver Burden in Alzheimer’s Disease,” The Gerontologist, Vol. 52, No. 1, 2011, pp. 89-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr117 [24] J. Grad and P. Sainsbury, “Mental Illness and the Fam- ily,” Lancet, Vol. 1, 1963, pp. 544-547. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(63)91339-4 [25] S. H. Zarit, K. E. Reever and J. Bach-Peterson, “Relatives of the Impaired Elderly: Correlates of Feelings of Bur- den,” Gerontologist, Vol. 20, No. 6, 1980, pp. 649-655. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/20.6.649 [26] Family Caregiver Alliance, “Women and Caregiving: Facts and Figures,” 2003. http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content_node.jsp? nodeid=892 [27] R. H. Fortinsky, H. Tennen, N. Frank and G. Affleck, “Health and Psychological Consequences of Caregiving,” In: C. Aldwin, C. Park and R. Spiro, Eds., Handbook of Health Psychology and Aging, Guilford, New York, 2007, pp. 227-249. [28] J. S. Rolland, “Families, Illness, & Disability: An Integra- tive Treatment Model,” Basic Books, New York, 1994. [29] T. Habib and S. Rahman, “Psycho-Social Aspects of AIDS as a Chronic Illness: Social Worker Role Perspective,” Antrocom Onlus, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2010, pp. 79-89 [30] J. Grater, “The Impact of Health Care Provider Commu- nication on Self-Efficacy and Care-Giver Burden in Older Spousal Oncology Caregivers,” Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, 2005, p. 121. [31] P. Thoits, “Social Support as Coping Assistance,” Jour- nal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 54, No. 4, 1986, pp. 416-423. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.54.4.416 [32] ANON, “What Is Caregivers’ Burden and What Causes It?” 2009. www.agingincanada.ca/What_is_caregiver_burden.htm [33] M. Chambers, A. Ryan and S. Connor, “Exploring the Emotional Support Needs and Coping Strategies of Fam- ily Carers,” Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2001, pp. 99-106. Open Access WJA  Assessing the Relationship between Caregivers Burden and Availability of Support for Family Caregivers’ of HIV/AIDS Patients in Calabar, South East Nigeria Open Access WJA 344 http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2850.2001.00360.x [34] C. Klienke, “Coping with Life Challenges,” Wadsworth, California, 1991. [35] J. S. Greenberg, M. M. Seltzer, M. W. Krauss and H. Kim, “The Differential Effects of Social Support on the Psy- chological Well-Being of Ageing Mothers of Adults with Mental Illness or Mental Retardation,” Family Relations, Vol. 46, No. 4, 1997, pp. 383-394. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/585098 [36] W. Haley, E. Levine, S. Brown and A. Bartolucci, “Stress, Appraisal, Coping and Social Support as Predictors of Adaptational Outcome among Demential Caregivers,” Psychology and Ageing, Vol. 2, No. 4, 1987, pp. 323-330. [37] P. Wilson, S. Moore, D. Rubin and P. Bartels, “Informal Caregivers of the Chronically Ill and Their Social Support: A Pilot Study,” Journal of Gerontological Social Work, Vol. 15, No. 1-2,1990, pp.155-169. [38] S. Turner and H. Street, “Assessing Carers’ Training Needs: A Pilot Inquiry,” Aging and Mental Health, Vol. 3, No. 2, 1999, pp. 173-178. [39] J. Hall, “Towards a Psychology of Caring,” British Jour- nal of Clinical Psychology, Vol. 29, No. 2, 1990, pp. 129- 144. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1990.tb00863.x [40] WHO, “Global Health Observatory (GHO),” Federal Mi- nistry of Health (FMOH), 2011. [41] R. A. Krueger, “Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research,” 2nd Edition, Sage, Newbury Park, 1994. [42] S. H. Zarit, “Family Care and Burden at the End of Life,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, Vol. 170, No. 12, 2004, pp. 1811-1812. [43] K. Chou, H. Chu, C. Tseng and R. Lu, “The Measurement of Caregiver Burden,” Journal of Medical Sciences, Vol. 23, No. 2, 2003, pp. 73-82. http://jms.ndmctsgh.edu.tw/2302073.pdf [44] A. Gibbs, “Focus Groups,” Social Research Update Issue 19, Guilford, 1997. http://sru.soc.surrey.ac.uk/SRU19.html [45] J. Sim, “Collecting and Analysing Qualitative Data: Issues Raised by the Focus Group,” Journal of Advanced Nurs- ing Vol. 28, No. 2, 1998, pp. 345-352. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.19 [46] R. Hebert, G. Bravo and M. Preville, “Reliability, Valid- ity and Reference Values of the Zarit Burden Interview for Assessing Informal Caregivers of Community Dwell- ing Older Persons with Dementia,” Canadian Journal on Aging, Vol. 19, No. 4, 2000, pp. 494-507. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0714980800012484 [47] E. Namey, G. Guest, L. Thairu and L. Johnson, “Data Re- duction Techniques for Large Qualitative Data Sets,” In: Handbook for Team-Based Qualitative Research, Row- man Altamira, 2008. [48] C. Nijber, M. Triemstra, R. Tempelear, R. Sanderman and G. A. Van den Bo, “Determinants of Caregiving Experi- ences and Mental Health of Partners of Cancer Patient,” Cancer, Vol. 86, No. 4, 1999, pp. 577-588. [49] R. Schulz and A. Quiltner, “Caregiving for Children and Adult with Chronic Conditions: Introduction to Special Is- sue,” Health Psychology, Vol. 17, No. 2, 1998, pp. 107- 111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0092707 [50] J. Mignone, C. Pindera, J. Davis, P. Migliardi, C. Harvey, M. Bendig, K. McKay-McNabb and L. Elliot, “Social Supports, Informal Caregiving and HIV/AIDS: A Com- munity-Based Study,” 2011. http://www.academia.edu/1241091/Social_Supports_Infor mal_Caregiving_and_HIV_AIDS_A_ Commu nity-based_S tudy [51] O. A. Akintola, “Gender Analysis of the Burden of Care on Family and Volunteer Caregivers in Uganda and South Africa,” Health Economics and HIV/AIDS Research Di- vision (HEARD), Durban, 2004. http://www.heard.org.za [52] United Nations, “We can End Poverty 2015, MDG 1: Eradicate Extreme Poverty & Hunger,” 2012. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals//poverty.shtml [53] “UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic: Execu- tive Summary,” 2008. [54] S. Reinhard, B. Given, N. Petlick and A. Bemis, “Sup- porting Family Caregivers in Providing Care,” Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2665/ [55] M. Scherbring, “Effect of Caregivers Perception of Pre- paredness on Burden in an Oncology Population,” On- cology Nursing Forum, Vol. 29, No. 6, 2002, pp. 70-76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1188/02.ONF.E70-E76 [56] R. Kohli, V. Purohit, L. Karve, V. Bhalerao, S. Karvande, S. SheelaRangan, R. Reddy, R. Paranjape and S. Sahay, “Caring for Caregivers of People Living with HIV in the Family: A Response to the HIV Pandemic from Two Ur- ban Slum Communities in Pune, India,” PLoS ONE, Vol. 7, No. 9, 2012, Article ID: e44989. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0044989 [57] M. Chambers, A. Ryan and S. Connor, “Exploring the Emotional Support Needs and Coping Strategies of Fam- ily Carers,” Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2001, pp. 99-106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2850.2001.00360.x [58] L. Rose, “Caring for Caregivers: Perceptions of Social Sup- port,” Journal of psychology Nursing and Mental Health Services, Vol. 35, No. 2, 1997, pp. 17-24.

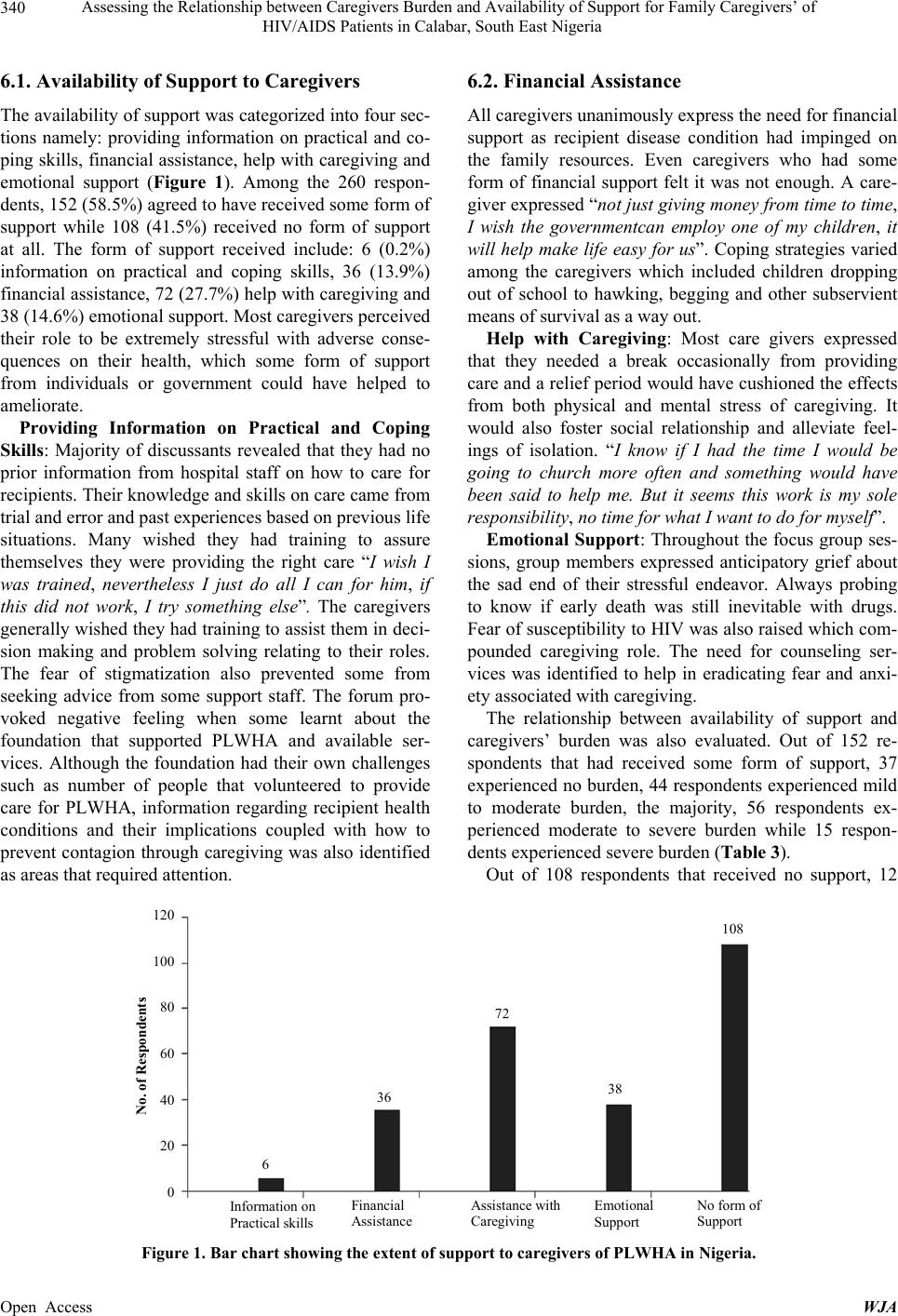

|