Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.12, 940-949 Published Online December 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.412136 Open Access 940 Lay Knowledge of Dyslexia Adrian Furnham Research Department o f Clinical, Educational and Health Ps ychology, University College London, London, UK Email: A.Furnham@ucl.ac.uk Received September 23rd, 201 3; revised October 27th, 2013; acce p te d N o v e mber 24th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Adrian Furnham. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons At- tribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2013 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Adrian Furnham. All Copyright © 2013 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. This study looks at the extent to which lay people believe many myths associated with dyslexia. It exam- ined attitudes and beliefs about the causes, manifestations and treatments for dyslexia in a British popula- tion sample. A community sample of 380 participants (158 Male; 212 Female) completed a 62-item ques- tionnaire on their attitudes to, and beliefs about, dyslexia. The statements were derived from various “dyslexia facts and myths” websites set up to help people understand dyslexia; academic research papers; and in-depth exploratory interviews with non-specialist people regarding their understanding of dyslexia. Item analysis showed participants were poorly informed about many aspects of dyslexia. Factor analysis returned a structure of latent attitudes in five factors (Characteristics, Biological and Social Causes, Treatment and Prevention). Regression analysis revealed that participant political orientation and educa- tion (formal and informal acquaintances with dyslexia sufferers) were the best predictors of attitudes concerning the behavioural manifestations, aetiology and treatments of dyslexia. Limitations and implica- tions of this research were considered. Keywords: Lay Beliefs; Myths; Knowledge; Understanding; Dyslexia Introduction Dyslexia is a term used by professionals to denote significant and persistent reading difficulties that affect 10% - 15% of English speaking populations (O’Hare, 2010). It is manifested in difficulty in attaining normal reading ability despite good teaching, motivation and intelligence. It has been conceptual- ized as a specific learning disorder, but there still remains de- bate out the precise definition and classification of the exact symptoms and epidemiology to define the syndrome. Dyslexia is often referred to as developmental dyslexia and it denotes difficulty in acquiring reading skills, often recognized during early school years. Acquired dyslexia on the other hand usually occurs as a result of physical trauma leading to reading difficulties after the skill was attained. In essence, the primary problems for a person/reader with dyslexia are word decoding and spelling, primarily because of their word-sounding or pho- nological system. Associated difficulties include poor short- term memory, problems with articulation and co-ordination as well as great difficulty in naming things (Sno wling, 1987). Ho w- ever, it is important to ensure the problem is not due to inade- quate educational opportunities, hearing or visual impairment, neurological disorders, or major socio-emotional difficulties. Dyslexia is evident when accurate and fluent word reading and/or spelling develops slowly, incompetently and with great difficulty. A person with dyslexia is an intelligent, poor-reader (Ellis, McDougal, & Monk, 1996) but often a person with low academic self-esteem and associated emotional symptoms and difficulties (Terras, Thompson, & Minnis, 2009). Papers aimed at doctors spelling out simple diagnostic points e.g. “Children with dyslexia have poor phonological awareness and in their early years demonstrate difficulties in vocabulary development and alphabetic knowledge” (O’Hare, 2010: p. 343). Over the past fifty years the growth of political, social and academic attention devoted to dyslexia as a specific and identi- fiable learning disability has spanned numerous disciplines including medicine, psychology and neurobiology. Today, ex- perts across all disciplines generally concur that dyslexia is likely to be, at least in part, neurological in origin (Eden & Flowers, 2009; Shaywitz, Shaywitz, Pugh, Fulbright, Mencl, Constable, Skudlarski, Fletcher, Lyon, & Gore, 2001). Yet, in spite of academic development, myths persist (often fueled by media sensationalism) regarding its causes and consequences in a literate society. This study looks at lay knowledge of dyslexia. This study is related to the literature on mental health literacy (Jorm, 2000) and lay theories of mental illness. Studies on adults (Jorm et al., 2004) and adolescents (Leighton, 2009, 2011) have shown that lay people confuse dyslexia with learning difficulties such as ADHD. They seem poorly informed about the nature of dys- lexia and how it can best be treated. Whereas experts and researchers are clear about what spe- cific symptoms are, and are not, associated with dyslexia (poor reading fluency, poor phonetic awareness, visual processing deficits) lay people are more likely to think in terms of “word blindness” spelling difficulties and poor reading skills. In the early 1960s it was proposed that there were three main causes for general reading backwardness: environmental factors  A. FURNHAM such as poor formal education/teaching and home life depriva- tion; emotional maladjustment; and/or some organic and con- stitutional factor. Finally, because dyslexia tends to run in fami- lies (affecting 50% of children with dyslexic parents) and some research has alluded to boys being more vulnerable than girls, it suggests that some genetic factors may also be contributory (Pennington & G i lger, 1996). The common debate among researchers is whether it is meaningful to think of a simple bell-shaped curve or continuum of normal reading ability with those significantly above average at the top and backward readers at the bottom. Some concur that reading ability is normally distributed and that reading difficulties are not a discrete entity but a linguistic cut-off point on a scale. Others argue for a different and more complex, multi-faceted cluster or pattern of cognitive skills. As with nearly all researched psychological phenomena experts point out that people with the problem are far from a homogeneous set and frequently fall into recognizable subgroups. This proc- ess of delineating sub-groups often helps a great deal with pre- cise diagnosis, prognosis and theory building (Brunswick, Mar- tin, & Marzano, 2010; Riddick, 1995). Several influential organizations concerned with dyslexia (International Dyslexia Association; World Federation of Neu- rology; UK Government/Rose report) have produced defini- tions of dyslexia. Further, over the past decade various theories have been developed and tested such as Magnocellular Deficit Theory (Stein, 2001). Periodically, academic papers question the very existence of dyslexia. For instance in 2009 a British MP (Graham Stringer, MP for Manchester Blackley) said that there is no such thing as dyslexia and that it is essentially a myth used to cover up bad teaching. He described dyslexia as a “fictional malady”, which hardly exists in other countries. He also reported that over 35,000 British students were receiving disability allowances costing the British taxpayer over £78 million. This sort of skep- ticism frequently surfaces. Defenders point out that dyslexics are different from poor readers because of their peculiar and specific errors in reading or spelling, despite evidence of nor- mal, if not high intelligence, and in spite of conventional teaching. Others point out that dyslexia seems a culture-bound syndrome (Cooper, 2010; Spencer, 2000). Indeed in Great Brit- ain there have been numerous programmes on dyslexia over the year. Other critics point to dyslexia as a fallacy according to socio-economic status. Notably, they comment on its preva- lence among the middle classes wherein affluent parents cannot or will not face the fact that their child(ren) are (disappointedly) not very bright and consequently, as a coping strategy, attempt to manipulate the education system to their advantage. Some regard this attack as damaging, hurtful, and deeply unjustified and possibly related to certain parents expecting far too much of their children. Similar debates and controversies have mani- fested for other identifiable developmental disorders, often found in children and adolescents. (e.g. Haworth-Hoeppner, 2000; McClelland & Crisp, 2001). One consequence of such skepticism is the number of web- sites and internet-based resources that exist to help confused or ignorant lay people seek clarification of the facts inherent in dyslexia. One example is Dyslexics.org.uk which sets out a number of “myths” followed by facts. Their format starts with definition, the symptoms and finally the “fact” (www.learning-inside-out.com). Their mere existence can be undoubtedly attributed to prevailing public ignorance about dyslexia which, when compared to other disorders, seems a topic rather under-researched. There have been a number of studies on teacher’s and lec- turer’s knowledge of basic language concepts and dyslexia showing that many seem poorly equipped to teach reading or spot dyslexics (Cameron & Nunkoosing, 2012; Cunningham et al., 2004, McCutcheon et al., 2002; Joshi et al., 2009; Moats, 2009; Regan & Woods, 2000). Wadlington and Wadlngton (2005) used their Dyslexia Belief Index and found the majority of the student and lecturer participants believed a number of misconceptions about dyslexia. Some papers have focused on the different beliefs of educational psychologists, parents of dyslexic children and special education needs experts (Paradice, 2001). Washburn et al. (2011) found in their study of 185 American teachers of elementary-aged children that they seemed to hold the common misconception that dyslexia is a visual processing deficit rather than a phonological processing deficit. Bell, McPhillips and Doveston (2011) noted how teachers had bio- logical, cognitive and behavioural conceptualisations of dys- lexia. Gwernan-Jones and Burden (2009) who investigated trainee teachers’ attitudes towards aspects of dyslexia surveyed 404 future British teachers from one university. Results showed that students accepted/endorsed the construct of dyslexia and be- lieved they could help and support dyslexic pupils, though how this was to be accomplished remains unclear. Females were more positive than males. But there were no differences ac- cording to the Post Graduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) course subject. Moreover, students who took a survey before and after teaching practice demonstrated some small changes across time in their attitudes towards dyslexia. Due to the absence of research literature on lay attitudes and beliefs about dyslexia the present study aims to unearth these and to examine whether the British public is in fact ignorant about dyslexia. The study has three aims: first to look at the range and endorsement of beliefs about dyslexia; second, through factor analysis, to look at the structure of these beliefs and third, to examine the relationships between lay theories and various demographics. Exploratory in design, no formal hy- potheses will be tested. Method Participants 380 participants took part in the present study, 158 of whom were male and 212 were female. Their mean age was 32.53 years (SD 14.4 years: Range 18 to 69 yrs). The majority of participants were of Caucasian background (66%) however other ethnic groups were represented including Asian (16%) and Afro-Caribbean (3%). In terms of educational attainment, 54% had A-levels, 27% a Bachelors degree and 12% a post graduate qualification. In all, 39% were single and 52% married. Their average annual income was £32,000 (National average: £26,000). The majority of participants described themselves as having few or no strongly held religious beliefs (as measured on a 7 point “not at all” to “very” religious scale. When asked their political orientation the vast majority (80%) ascribed to having moderately liberal beliefs (again measured on a 7 point Left-Right wing scale). Lastly, participants were asked if they had been diagnosed with dyslexia and 345 responded no, 12 yes Open Access 941  A. FURNHAM and 10 were unsure. The majority of participants (66%) knew someone with dyslexia. This was not a cross section of the population with a bias to better educated, higher social class participants. Materials and Procedure Participants completed a 62-item questionnaire. The items are shown in Table 1. The items were derived from three main sources and subsequently used as the basis for attitude state- ments. First, various websites have lists of myths about dys- lexia and approximately 10 of these were utilized (see Table 1). The web was interrogated for all cites aimed at parents and the public concerning dyslexia, reading difficulties and school fail- ure. Second, the remaining items were derived from academic journal articles in the area of mental health literacy. Third, open-ended interviews with 10 non spcialists about dyslexia. The aim was to get a comprehensive list of statements con- cerning general beliefs about dyslexia. In total, approximately 80 statements were collated. These were then subjected to an initial pilot study based on interviewing 20 people who pro- vided their responses in a structured interview format. They were asked to respond to each question and then reflect upon it for its clarity and comprehensibility. They were also asked about their knowledge of dyslexia. Following the pilot, ap- proximately 20 items were discarded (as being unclear or lead- ing to floor or ceiling effects) and a number were then modified. The final questionnaire contained 62 items, hopefully covering all aspects of dyslexia. Participants were asked the extent to which they agreed with the statements, each anchored by Not sure (1) Strongly disagree (2) and Strongly agree (6). These were collapsed into three categories (agree, not sure, disagree) for easier interpretation (see Table 1). Following completion of the questionnaire items, participants were asked if they themselves had ever been diagnosed with dyslexia and whether they knew of anyone with the condition. Participants further provided some demographic information, including their highest educational attainment, political orienta- tion (on a 7 point Left Wing—Right Wing scale), religiousness (on a 7 point Not at all—Very scale) and current annual income. Ethical approval was first sought and approved by the de- partmental committee. Participants were approached by five research assistants in a number of public settings including libraries, coffee bars and railway stations. They were instructed to attempt to get a cross section of the population in terms of sex, age, race and social class. Approximately one-third of those approached refused their participation on the basis that they were too busy, and in a hurry. Of the remainder who gave their consent, 93% provided complete data, which was used in the study. The questionnaire was completed anonymously. Following successful completion of the questionnaire, partici- pants were thanked for their participation. They were not re- munerated but debriefed concerning the nature of the study. Many expressed considerable interest. Results Table 1 shows the responses to individual items. Approxi- mately half the participants considered dyslexia to be a learning disability characterized by problems with words and language (items 43, 44, 47, 49) but were unsure whether this was due to less reading than would be expected for their age or indeed whether the problem is unique to poor reading (items 34, 48, 50). The majority of participants believed that dyslexia cannot be solely attributed to a lack of proficiency with dictionaries (items 2, 4, 6). Participants generally disagreed about the exis- tence of neurological causes of dyslexia (items 41, 51, 32, 58) but were unsure about a genetic causal link (items 1, 56, 61). The majority believed that the education system and workplace have a duty to provide courses/clubs to detect and help those with dyslexia (items 15, 22, 18) but not insofar that every dys- lexic child should receive one-to-one assistance (item 21). The majori ty of participants believed that individuals can bene- fit from informal skills learning (items 11, 28) but they were unsure as to the extended benefits provided with formal spe- cialist literacy instruction (items 37, 54). Factor Analy sis In order to ascertain any factorial structure in the measure, data were subjected to Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure verified the sampling adequacy for the analysis (0.822) (Kaiser, 1974). In addition, all KMO values for individual items were above 0.5, supporting their retention in the analysis. The satisfactory results therefore suggest the matrix is appropriate for factor analysis. Using an orthogonal rotation (Varimax), items that loaded at or above 0.40 were retained (Ferguson & Cox, 1993). After careful examination of eigenvalues, proportion of vari- ance explained and scree plot criterion, five distinct factors were identified and suggested for rotation. Items that loaded significantly onto more than one factor and where the discrep- ancy was large (above 0.2), were assumed to load on the factor with the highest loading. Where the difference was small, the variable was removed. A final inspection of the commonalities revealed that all but one (item 30) exceeded 0.5, suggesting the factor solution accounted for at least half of each item’s vari- ance. The final matrix contained 26 items across five factors, accounting for 62.07% of the total variance (details from the first author). Table 2 shows the mean scores, the alpha coefficient scores and factor analytic results. The first factor had 7 items loaded .40 or above (36, 43, 44, 47, 48, 49, 50) and accounted for 6.30% of the variance. This was labelled Characteristics because it reflected participant awareness of the constituent symptoms of dyslexia. Within this factor, all items had mean scores over 3, suggesting that participants generally agreed on the symptoms of dyslexia. The second factor had 5 items loaded 0.50 or above (41, 51, 32, 56, 58) and accounted for 5.97% of the variance. This was labelled Biological Causes because it reflected participant acknowledgement and endorse- ment of biological causes of dyslexia. Within this factor all of the items had mean scores of below 4 suggesting that partici- pants disagreed or at most unsure of the biological causes of dyslexia. The third factor had 6 items loaded .40 or above (22, 15, 21, 61, 18, 1) and accounted for 5.00% of the variance. This was labelled Treatments because items reflected participant attitudes towards treating dyslexia. Within this factor all but one of the items had mean scores of over 4 suggesting that par- ticipants generally agreed that dyslexia could be treated using different methods. The fourth factor had items loaded .50 or above (2, 4, 6) and accounted for 3.63% of the variance. This was labelled Social Causes because it reflected participant atti- tudes towards the use (or lack of) of dictionaries and other learning aids as the cause for dyslexia. Within this factor, all Open Access 942  A. FURNHAM Open Access 943 Table 1. Mean scores, standard deviation s and frequency (%) of participant responses to individual items. Frequency (%) Dyslexia Myth or Fact Corresponding source Mean Scores SD Not sure DisagreeAgree 1) People cannot help being dyslexic—it is in their genetic make-up www.dyslexics.org.uk 4.55 1.64 11.3 11.1 67.1 2) Parents should ensure they have learning aids (e.g. dictiona ries) in the house to prevent dyslexia www.prometheantrust.org 3.34 1.52 11.6 42.8 27.1 3) Once a person is dyslexic, they will al ways be so. www.prometheantrust.org www.uws.ac.uk 3.62 1.71 18.9 26.9 40.3 4) It is essential that primary school children are taught how to use a dictionary to pre vent dyslexia. www.dys-add.com 3.31 1.48 10.0 44.4 25.0 5) The escalating prevalence of dyslexia is caused by the breakdown of the family unit since the 1960s. 2.55 1.18 16.3 62.4 7.4 6) Spending 100 hours with a dictionary and an English teacher would eradicate dyslexia in every British child. 2.57 1.19 15.0 64.2 8.6 7) Dyslexia comes with too much stigma to ever be completely cured.www.uws.ac.uk 3.06 1.37 14.5 47.4 17.9 8) Dyslexic people are simply of lower intelligence and efforts to prove otherwise are a waste of the tax payer’s money. www.scolasticred.com 2.36 .97 3.2 86.1 5.5 9) Dyslexia is a myth. www.dys-add.com 2.48 1.06 4.7 80 7.4 10) Many dyslexics are extremely intelligent individuals. www.learning-inside-out.com4.55 1.71 12.6 7.35 59.7 11) Curing dyslexia must start with educating the parents if it is to have long-term benefits. 4.08 1.64 12.4 16.9 51.8 12) An adult with dyslexia should resign themselves to their fate. www.uws.ac.uk 2.54 1.02 2.6 82.3 6.8 13) The growth of dyslexia is the r esult of ineffective liberal changes in how we teach children to read. 2.83 1.38 16.8 52.9 15 14) The increase in technology to facilitate our fast paced lifestyle has made it too easy for people to succeed without good literacy. 4.01 1.54 8.7 25.8 51.5 15) Teachers should receive training to detect dyslexics symptoms from the offset. 5.28 1.09 2.6 3.9 87.6 16) Dyslexia is a difficulty with language, not being unintelligent. www.scolasticred.com 5.21 1.28 5.3 3.4 85.8 17) Teaching children foreign languages from an early age would improve literacy in their native language and prevent dyslexia. 2.95 1.60 29.7 24.7 18.9 18) Companie s should provi de free course s for dyslexic employee s t o i mprove staff lite r acy. 4.24 1.47 8.2 15.6 52.1 19) Today, there is too much emphasis placed on tertiary and professional occupations making dyslexia more noticeable. 3.35 1.50 20.3 22.6 24.5 20) Lazy, demotivated children are thought of as dyslexic mainly because they “could not bother to learn to read”. www.dys-add.com 3.29 1.42 10 45.5 23.9 21) Every dyslexic child in the education system should get a personal c oach. 3.53 1.45 12.1 33.4 28.9 22) Self-help groups/clubs in schools should be established where dyslexic children can help each other. 4.51 1.50 9.7 9 66.1 23) Those with dy slexia ne ed support and must be taught survival skills to cope with dyslexia. 4.75 1.28 3.9 9.2 72.9 24) More boys than girls are dyslexic. www.dys-add.com 2.43 1.76 57.1 5.2 18.9 25) Students claim dyslexia simply to get extra exam time. www.metro.co.uk/news 3.31 1.46 12.4 37.9 24.5 26) Few people are perfect spellers—the boundary between ‘dy s lexia’ and poor English is poorly defined. 3.75 1.57 14.2 23.4 41.5 27) Our multicultural society is making the teaching of English literacy increasingly difficult. 3.46 1.49 10.8 39.7 30.8 28) Practising grammar and vocabulary in the hom e every evening would improve dyslexia at any age. www.dys-add.com 3.90 1.71 17.9 16.6 52.9 29) Embryos that do not receive enough intellectual stimulation in the womb are more likely to develop dyslexia. 2.08 1.20 39.5 43.9 4.2 30) Widely advertised national help lines would help reduce any stigma at tached to dyslexia, if not reduce some of the symptoms. 3.62 1.56 13.2 27.6 36.8  A. FURNHAM Continued 31) From kindergarten, all dyslexic childre n should be put into specialised schools. 2.64 1.06 4.5 77.6 8.4 32) Dyslexia is a biological dysfunction present from birth. www.learning-inside-out.com3.29 1.91 33.4 13.43 39.2 33) “ Listenin g to books ” a re a n excellent tool for both learning and leisure.www.dys-add.com 4.69 1.35 6.8 6.6 67.9 34) Dyslexia sufferers should attend regular opticians’ appointments to prevent poor e ye sight being a contributing factor. www.dyslexics.org.uk www.dys-add.com 3.50 1.58 15 29.5 67.9 35) Dyslexic symptoms r ange from mil d t o s evere. 4.94 1.55 10.3 2.4 81 36) Dyslexics usually have poor self-esteem. www.scolasticred.com www.uws.ac.uk 3.52 1.62 19.2 22.8 35.3 37) Dyslexia can be cured by intensive and special training. www.dys-add.com 3.28 1.70 26.8 21.1 31.8 38) Middle class parents cannot face the fact a child of theirs may have low int elligence and prefer to call it dyslexia. Riddick, B. (1995) 3.46 1.56 13.2 33.4 30 39) Therapy for dyslexia should occur in the same environment in which people learn (e.g. sc ho ols, university, training courses). 4.83 1.28 5 8.1 75 40) Dyslexia is a difficulty w i t h learning in s o me academic areas but not others. www.learning-inside-out.com3.82 1.85 21.1 16.4 50.6 41) The dyslexic individual is born with dyslexic tendencies due to differences in brain s tructure and/or function. www.learning-inside-out.com2.94 1.99 46.3 7.6 34.8 42) When reading, dyslexic people often take longer to recognise a word they know. www.learning-inside-out.com4.74 1.48 10.8 1.9 78.2 43) Dyslexic people have more trouble sounding o ut a word or automatically remembering what sounds the letters make. www.learning-inside-out.com3.56 1.91 29.5 11.9 46.3 44) Dyslexic pe ople have prob lems related to t he ability to notice, remember, pronounce, identify and manipulate the sounds of the language .www.learning-inside-out.com3.63 1.84 25.0 14.2 45.5 45) Most dyslexic people show at least average ability and intelligence. www.learning-inside-out.com4.09 1.71 17.4 8.2 51.8 46) Even with learning opportunities, dyslexic people still struggle more than other s o f the same age, gr ade and ability. www.learning-inside-out.com3.99 1.57 13.4 17.1 49.7 47) When reading is hard, dysle xic people rea d as much as others and this results in the ir learning ne w words and their meanings more slowly. www.learning-inside-out.com3.99 1.80 21.1 7.9 59.6 48) Dyslexic people often do not read as much as others and this r esults in their learning new words and their meanings more slowly. www.learning-inside-out.com3.46 1.69 20.3 27.2 36.1 49) Dyslexics d o not easily l earn various aspects of langua ge and they often have a hard time learning vocabulary a nd un derstanding language concepts as they go through school. www.learning-inside-out.com3.84 1.74 20.8 11.6 50.5 50) Dyslexics form a special and identifiable category of poor readers.www.dyslexics.org.uk 3.51 1.59 17.4 27.1 33.1 51) Dyslexia is a specific brain weakness; a genetically-based, neurological difficulty with sound awareness and processing skills. www.dyslexics.org.uk 2.84 1.87 43.9 12.6 29.4 52) All children who fail to learn the alphabet from conventional education by the age of 7 - 8 years, have a “specific learning difficulty consistent wit h d yslexia”. www.dyslexics.org.uk 2.44 1.46 38.4 35.6 11.3 53) The prevalence of dyslexia is estimated to be somewhere between 4% - 8% of the population in English-speaking countries. www.dyslexics.org.uk 2.09 1.69 67.6 3.7 16.1 54) Those wh o h ave bee n “p rofessionally” diagnosed with as having Dyslexia need a special sort of literacy instruction which is different from that deemed suitable for “ordinary” poor-education readers. www.dyslexics.org.uk 3.54 1.82 42.4 11.8 30.8 55) Dyslexics do not just have inaccurate reading and spelling; other signs are used to identify dyslexia such as poor short-term memory, sequencing pr o bl ems and ra pid naming deficits. www.dyslexics.org.uk 2.95 1.89 42.4 11.8 30.8 56) Dyslexia is caused by inherited, faulty genes with evidence coming from studies of twins. www.dyslexics.org.uk 2.29 1.70 58.2 10.8 30.8 57) Dyslexia is a visual problem-dyslexics see words backwards a nd letter reversed. www.dyslexics.org.uk 3.07 1.82 32.6 23.1 31.8 58) Brain scan studies show tha t dyslexics brains work differently from those of non-dyslexics. www.dyslexics.org.uk 2.78 1.91 48.2 8.9 30.3 59) Dyslexics a r e compensa ted for their lac k of p honologic al and reading ability by being gifted in the artistic/v i suo-spatial sphere. www.dyslexics.org.uk 2.98 1.76 37.4 13.9 23.4 Open Access 944  A. FURNHAM Open Access 945 Continued 60) Dyslexia can be properly dia gnosed by an educational psychologist using special tests. www.dyslexics.org.uk 4.65 1.58 12.4 3.5 73.7 61) Dyslexia can be found world-wide. www.dyslexics.org.uk 4.80 1.69 12.9 4.8 76.3 62) Dyslexia can be cured or helped by techniques such as special balancing exercises, fish-oils, glas ses with tinted le n ses, vision exercises, modeling clay letters, and inner-ear-improving medications.www.dyslexics.org.uk 2.53 1.64 41.6 26.6 18.4 Table 2. Mean scores, alpha coefficient s , variance accounted for, and number of items within the five factors. Factor Mean Alpha % of variance N of items 1. 25.83 .79 6.30 7 2. 14.20 .80 5.97 5 3. 18.74 .69 5.00 6 4. 9.23 .69 3.63 3 5. 27.11 .63 3.47 5 items had mean scores of below 4 suggesting that participants generally disagreed with this as an explanation for dyslexia. The fifth factor had 5 items loaded 0.40 or above (34, 11, 37, 54, 28) and accounted for 3.47% of the variance. This was la- belled Prevention as it consisted of items relating to methods used to prevent dyslexia. All but one of the items within this factor had mean scores of below 4 suggesting that participants generally disagreed or at most were unsure, of the methods used to prevent dyslexia. Table 3 shows the factor inter-correlations, which are all positive and significant. One possible interpretation is that in knowing one aspect of dyslexia (e.g. cause), participants were likely to have related beliefs regarding another aspect of the condition (e.g. characteristics). Q-Sort As participants were not required to have detailed knowledge of the construct, this study further adopted a Q-Sort methodol- ogy to thematically classify the data. It is a method widely used in the social sciences, particularly when investigating subjective attitudinal development, wherein a structure of latent attitudes can be identified. Three independent researchers thematically classified the statements based on their content. Results are shown in Table 4. Multiple Re gression Analysis In an attempt to determine the factors mediating attitudes towards the different aspects of dyslexia in the UK, five inde- pendent multiple regression analyses were performed. Various participant demographic factors served as the predictor vari- ables as well as responses to the two questions regarding par- ticipant’s personal history and knowledge of others with dys- lexia. In a model containing educational attainment, political ori- entation and personal history of dyslexia when predicting atti- tudes towards characteristics of dyslexia, results showed that political orientation (β = 0.115, t = 2.06, p < 0.05) was the only significant predictor in the equation. A significant model emerged: F (3, 319) = 3.07, p < 0.05 and the model explained 2.8% of the variance (Adjusted R2 = 0.019) in the attitude scores towards dyslexia characteristics. Results suggest that individuals with right wing political affiliations were more like- ly to consider dyslexia a learning problem related to poor read- ing and phonology. In the second regression analysis, the model contained edu- cational attainment, political orientation, previous history of dyslexia and knowledge of an acquaintance with dyslexia and attitude scores concerning the biological causes of dyslexia as the criterion variable. Results showed that both political orien- tation (β = 0.111, t = 2.02, p < 0.05) and knowing an acquaint- ance with dyslexia (β = 0.116, t = 2.12, p < 0.05) were signifi- cant predictors in the equation, with educational attainment just failing to reach significance (p = 0.07). A significant model emerged: F (4, 323) = 3.92, p < 0.01 and the model explained 4.6% of the variance (Adjusted R2 = 0.034) in attitudes towards the biological causes of dyslexia. Results suggest that individu- als with right wing political affiliations were more likely to consider dyslexia the result of a biological and/or genetic defect, as were those who knew of individuals with the condition. In attempting to predict lay attitudes towards treatments of dyslexia, a model containing political orientation, personal history and knowledge of another person with dyslexia, educa- tional attainment and participant age as the independent vari- ables and attitudes towards treatment as the criterion variable was computed. Results showed that political orientation (β = 0.137, t = 2.44, p < 0.05) was the only significant predictor in the equation. A significant model emerged: F (5, 313) = 2.54, p < 0.05 and the model explained 3.9% of the variance (Adjusted R2 = 0.024) in attitudes towards treatment of dyslexia. Results suggest that participants with right wing ideology are more likely to believe that dyslexia is treatable via the use of various methods. In a model containing political orientation, knowledge of an acquaintance with dyslexia, participant gender and participant ethnicity as independent variables and attitudes towards social causes of dyslexia as the criterion variable, results showed that participant political orientation (β = 0.138, t = 2.55, p < 0.05) and ethnicity (β = 0.149, t = 2.73, p < 0.01) were significant predictors in the equation. A significant model emerged: F (4, 324) = 4.44, p < 0.01 and the model explained 5.2% of the vari- ance (Adjusted R2 = 0.040) in attitudes towards social causes of dyslexia. Results suggest that participants with left wing politi- cal affiliations and of Caucasian descent were least likely to  A. FURNHAM Table 3. Inter-correlati o ns between t h e f i v e fa c t o rs. Characteristics Biological Causes Treatment Social Causes Prevention Characteristics 0.42** 0.29** 0.52** 0.37** Biological Causes 0.11* 0.39** 0.38** Treatment 0.32** 0.16** Social Causes 0.34** Prevention **p < 0.01 *< 0.05. Table 4. Dyslexia Q-Sort analysis. Group Items General Causes 5. The escalading prevalence of dyslexia is caused by the br eakdown of the family unit since the 1960s. 13. The growth of dyslexia is the result of ineffective liberal changes in how we teach children to read. 14. The increase in technology to facilitate our fast paced lifestyle has made it too easy for people to succeed without good literacy. 29. Embryos that do not receive enough intellectual stimulation in the womb are more likely to develop dyslexia. 32. Dyslexia is a biological dysfunction present from birth. 41. The dysle xic individual is born with dyslexic tendencies due to differe nces in brain structure and/or functio n. 58. Brain sca n studies show that dyslexics brains work differently from those of non-dyslexics. Genetic Causes 1. People ca nnot help being dyslexic—it is in thei r g enetic make -u p. 51. Dyslexia is a specific bra i n weakness; a genetically-based, neurological difficulty with sound awareness and processing skills. 56. Dyslexia is caused by inherited, faulty genes with evidence coming from studies of tw ins. Prevention 2. Parents should ensure they have learning aids (e.g. dictionaries) in the house to prevent dyslexia. 4. It is essent ial that primary school children are ta ug ht how to use a dictionary to prevent dyslexia. 17. Teaching children foreign languages from an early age would improve literacy in their native language and prevent dys lex ia. Treatment 6. Spending 1 00 hours with a dictionary and an English teach would eradicat e dyslexia in every British child. 11. Curing dyslexia must sta rt with educating the parents if it is to have long-term benefits. 28. Practising grammar and vocabulary in the home every evening would improve dyslexia at any age. 37. Dyslexia can be cure by intensive and special training. 62. Dyslexia can be cured or helped by techniques such as special balancing exercises, fish-oils, glasses with tinted lenses, vision exercises, modelling clay letters, and inner-ear-im proving medications. Characteristics 20. Lazy, demotivated children are thought of as dyslexic mainly because they “ c ould not bother to learn to read”. 26. Few people are perfect spellers—the boundary between “dyslexia” and poor English is poorly defined. 35. Dyslexic symptoms range from mild to seve re. 36. Dyslexics usually have poor self-esteem. 40. Dyslexia is a difficulty wit h learning in some academic areas but not others. 46. Even with learn ing opportunities, dyslexic people still struggle more than others of the same age, grade and ability. 47. When reading is hard, dyslexic people read as much as others and this results in their learning new words and their meanings more slowly. 48. Dyslexic people often d o not read as much as others and this re sults in their learning new words and their meanings more slowly. 50. Dyslexics form a special and identifiable category of poor readers. Education 15. Teachers should receive training to detect dyslexics symptoms from the offset. 18. Companies should provide free courses for dyslexic employees to improve staff literacy. 21. Every dyslexic child in t he education system should get a personal coach. 22. Self-help groups/clubs in schools should be established where dyslexic children can help each other. 30. Widely advertised national help lines would help red uce any stigma attached to dysle xia, if not reduce some of the symptoms. Stigma 7. Dyslexia comes with too much stigma to ever be completely cured. 38. Middle class parents cannot face the fact a child of theirs may have low intelligence and prefer to call it dyslexia. Prevalence 24. More boys than girls are dyslexic. 53. The prevalence of dyslexia is estimated to be somewhere between 4% - 8% of the population in English-speaking c ountries. 61. Dyslexia can be found world-wide. Diagnosis 54. Those who have been “professionally” diagnosed with as having Dyslexia nee d a special sort of lite racy instruction which is different from that deemed suitable for ‘ordinary’ poor-education readers. 60. Dyslexia can be properly diagnosed by an educational psychologist using special tests. Cognitive Abilities 8. Dyslexic people are sim ply of lower intelligence and efforts to prove otherw ise are a waste of the tax payer’s money. 10. Many dy slexics are extremely intelli gent individuals. 16. Dyslexia is a difficulty w ith l anguage, not being unintelligent. 45. Most dyslexic people show a t least average ability and intelligence. Sympt oms 42. When readi ng, dyslexic people often take longer to recognize a word they know. 43. Dyslexic people have more trouble sounding out a word or automatic ally remembering what sounds the letters make. 44. Dyslexic people have proble ms related to the a bility to notice, remember, pronounce, identify and manipula te the sounds of the language. 49. Dyslexics do not easily l earn various aspects of language and they often have a hard time learning vocabulary and understanding language concepts as they go through school. Misc: 3, 9, 12, 19, 23, 25, 27, 31, 33, 34, 39, 52, 55, 57, 59. Open Access 946  A. FURNHAM believe that not possessing and utilising a dictionary causes dyslexia. In the final regression analysis, the model contained partici- pant age, ethnicity, educational attainment, political orientation, previous history of dyslexia and knowledge of an acquaintance with dyslexia and attitudes towards prevention of dyslexia as the criterion variable. Results showed that knowing someone with dyslexia was the only significant predictor (β = 0.318, t = 5.83, p < 0.001). A significant model emerged: F (6, 309) = 6.62, p < 0.01 and the model explained 11.4% of the variance (Adjusted R2 = 0.097) in attitudes towards treatments of dys- lexia. Results suggest that knowing people with dyslexia pre- dicts attitudes towards the various prevention programmes avai- lable for dyslexia. Discussion The aim of this study was to investigate lay theories of dys- lexia. The present findings suggest a clear pattern of lay atti- tudes towards various aspects the characteristics, causes, pre- vention and treatment of dyslexia in the UK. The five factors revealed via factor analysis lend some support to the argument that research questions about lay theories seem to be concerned with etiology, structure, relationships, function, stability and behavior consequences (Furnham, 1988). Finally, supporting Gwernan-Jones and Burden (2009), the findings attest to the lay belief that individuals with dyslexia can be helped with special- ist learning. In addition, attempts to ascertain demographics that predict attitudes successfully returned consistent predictors of dyslexia-related attitudes. This supports previous studies that have shown clear links between lay theories and various demo- graphic variables (Clark & Binks, 1996), including ethnic background (Hall & Tucker, 1985) and prior knowledge (Arn, Ottosom, & Perris, 1971). The finding that participants generally considered the char- acteristics of dyslexia to be a learning disability characterized by problems with words and language suggests that participants had a modest awareness of what constitutes clinically diag- nosed dyslexia. Regression analyses revealed that participant political orientation was the sole predictor of this finding. Specifically, participants self-reporting right wing political ideology were more likely to consider dyslexia a learning dis- ability characterized by poor reading, difficulty with learning new words and phonology. Over the last fifty years there has been a greater awareness and understanding of dyslexia, made possible by research ad- vances, media portrayal and social taboos. Whilst academic debate continues over the term “dyslexia” and its usefulness in explaining developmental language-related difficulties (e.g. Kerr, 2001), the present findings suggest that people are gener- ally well informed of its constituent symptoms. Movement away from descriptive labels in the 1960’s, including the “mentally retarded” used to explain the failings of the lower classes and the less stigmatizing “learning difficulties” to ex- plain that of the middle classes, clearly highlights awareness and understanding advancements of what is currently recog- nized as “dyslexia”. The finding that participants disagreed with or at most were unsure of the neuro-biological causes of dyslexia, including brain abnormalities, suggests a general ignorance to scientific research evidence documented over recent years. On the other hand, the majority of participants believed that dyslexia is, at least in part, genetic and found across the world. Thus, partici- pants were generally open to other explanations for the cause of dyslexia insofar that they believe it to be a heritable condition however the negative attitudes towards neurobiological causes of dyslexia suggests that participants were less open to dyslexia being a complex mu lt i-causally determined disability. Regression analyses revealed that political orientation and knowing other people with dyslexia were the significant pre- dictors of such attitudes. Specifically, participants self-reporting left wing political ideology and who knew of at least one per- son with dyslexia were less likely to endorse the biological origins of dyslexia. This result is surprising and does not lend support to previous lay theories research on psychiatric disor- ders, suggesting that having friends with psychiatric disorders results in more positive attitudes and greater understanding of their etiology (Furnham, 2009). One finding that participants were generally unsure or at most disagreed with prevention methods for dyslexia suggests a lack of detailed understanding in the participants what such measures entail and their value. Regression analyses revealed that knowing people with dys- lexia resulted in more scepticism over the usefulness of prac- ticing grammar, specialist training or educating the parents. It is likely that by knowing people with dyslexia participants would have firsthand experience of the disability and its potential severity, thus questioning whether they would have prevented language problems from the offset. In terms of limitations, the authors acknowledge that whilst the present findings attest to the variability in attitudes towards and knowledge of dyslexia, the sample tested were predomi- nantly well-educated, middle class, young people and thus cau- tion must be exercised when extrapolating the present findings to other age groups. Thus, the study used a convenience rather than representative sample. It is possible that lay theories of an older or working class sample would include more myths than facts of dyslexia. In addition, the dyslexia dimensions identified in the present study are, to some extent, inter-related, inter- dependent and not mutually exclusive. There are indeed other myths that this study did not assess and it may have been ad- visable to look at myths with various features of dyslexia such as occurance, diagnosis, aetiology, treatment etc. Future re- search should replicate this study to clarify whether the dimen- sions are related or whether the present results are in fact attrib- utable to methodological limitations. Revision of the question- naire may also be warranted with items both added and re- moved Taken together, the present results suggest that lay people show modest curiosity and understanding but also ignorance and naivety with regard to the multifaceted learning disorder of dyslexia. They suggest that educational programs are required to improve learning difficulties literacy in relation to dyslexia among the general public, teachers and parents. Schools may be particularly encouraged to do this. Given the potential implica- tions for stigmatization, childhood development and career success, it is paramount that perceptions of dyslexia in a literate country continues to be worthy of research attention. REFERENCES Arn, L., Ottosom, J., & Perris, C. (1971). Attitudes towards mental disorder and mental care in university students. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 17, 270-274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002076407101700403 Open Access 947  A. FURNHAM Bell, S., McPhillips, T., & Doveston, M. (2011). How do teachers in Ireland and England conceptualise dyslexia. Journal of Research in Reading, 34, 171-192. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2009.01419.x Brunswick., N., Martin, G., & Marzano, L. (2010). Visuospatial supe- riority in developmental dyslexia: myth or reality. Learning and In- dividual Differences, 20, 421-426. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2010.04.007 Cameron, H., & Nunkoosing, K. (2012). Lecturer perspectives on dys- lexia and dyslexic students within one faculty of one university in England. Teaching in Higher Education, 17, 341-35 2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2011.641002 Chang, W. C. (1985). A cross cultural study of depressive symptoma- tology. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry, 9, 295-315. Chang, W. C. (1988). The nature of the self: A transcultural view. Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review, 25, 169-189. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/136346158802500301 Clark A., & Binks, N. M. (1996) Relation of age and education to atti- tudes toward mental illness. Psychological Reports, 19, 649-650. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1966.19.2.649 Cooper, R. (2010). Are culture-bound syndromes as real as universally- occurring disorders. Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 41, 325-332. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2010.10.003 Cunningham, A., Perry, K., Stanovich, K., & Stanovich, P. (2004). Dis- ciplinary knowledge of K-3 teachers and their knowledge calibration in the domain of early literacy. Annals of Dyslexia, 54, 139-167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11881-004-0007-y Eden, G., & Flowers, L. (2009). Skill acquisition, reading and dyslexia. New York: New York Academy of Sciences. Ellis, A., McDougall, S., & Monk, A. (1996). Are dyslexics different? Dyslexia, 2, 31- 58 http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0909(199602)2:1<31::AID-DY S34>3.0.CO;2-0 Ferguson, E., & Cox, T. (1993). Exploratory factor analysis: A user’s guide. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 1, 84-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.1993.tb00092.x Fernando, S. (1988). Race and culture in Psychiatry. Aldershot: Gower. Furnham, A. (1988). Lay theories. Oxford: Pergamon. Furnham, A., & Malik, R. (1994). Cross-cultural beliefs about “depres- sion”. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 40, 106-123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002076409404000203 Gwernan-Jones, R., & Burden, R. (2009). Are they just lazy? Student teachers’ attitudes about dyslexia. Dyslexia, 16, 66-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/dys.393 Hall. L., & Tucker, C. (1985). Relationships between ethnicity, concep- tions of mental illness, and attitudes associated with seeking psycho- logical help. Psychological Reports, 57, 907-916. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1985.57.3.907 Haworth-Hoeppner, S. (2000). The critical shapes of body image: The role of culture and families in the production of eating disorders. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 212-227 http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00212.x Helman, C. (1990). Culture, health and illness. London: Wright. Jorm, A. (2000). Mental health literacy: Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry, 177, 396-401. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.177.5.396 Jorm, A., Kelly, C., Wright, A., Parsl o w, R., Ha rris, M., & Mc Gorr y, P. (2006). Belief if dealing with depression alone. Journal of Affective Disorders, 96, 59-65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2006.05.018 Joshi, R., Binks, E., Hougen, M., Dahlgren, M., Ocker-Dean, E., & Smith, D. (2009) Why elementary teachers might be inade-quately prepared to teach reading. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42, 392- 402. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022219409338736 Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psy-chometrika, 39, 31-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02291575 Kerr, H. (2001). Learned helplessness and dyslexia: A carts and horses issue? Literacy, 35, 82-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9345.00166 Kleinman, A. (1980). Depression, somatisation and the new “crosscul- tural psychiatry”. Social Science and Medicine, 11, 269-276. Lee, S. (1997). How lay is lay? Chinese students’ perceptions of anore- xia nervosa in Hong Kong. Social Science and Medicine, 44, 491- 502. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00168-2 Leff, J. (1988). Psychiatry around the globe. London: G a s k e ll . Leighton, S. (2009) Adolescents’ understanding of mental health prob- lems: Conceptual confusion. Journal of Public Mental Health, 8, 4- 14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17465729200900009 Leighton, S. (2010). Using a vignette-based questionnaire to explore adolescents’ understanding of mental health issues. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 15, 231-250. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359104509340234 McClelland, L., & Crisp, A. (2001). Anorexia nervosa and social class. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29, 150-156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(200103)29:2<150::AID-EAT1 004>3.0.CO;2-I McCutchen, D., Ab bott, R., Green, L., Be retvas, N. Cox, S., Po tter, N., Quiroga, T., & Gray, A. (2002) Beginning literacy: Links among teacher knowledge, teacher practice, and student learning. Journal of Learning Disability, 35, 69-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002221940203500106 Moats, L. (1994). The missing foundation in teacher education: Knowl- edge of the structure of spoken and written language. Annals of Dys- lexia, 44, 81-102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02648156 Moats, L. (2009) Still wanted: Teachers with knowledge of language. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42, 387-391. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022219409338735 O'Hare, A. (2010). Dyslexia: What do paediatricians need to know? Paediatrics and Child Health, 20, 338-343. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paed.2010.04.004 Osmond, J. (1993). The reality of dyslexia. Lo nd o n : C as s e ll . Paradice, R. (2001). An investigation into the social construction of dyslexia. Educational Psychology in Practice, 17, 213-225. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02667360120072747 Pennington, B. F., & Gilger, J. W. (1996). How is dyslexia transmitted? In C. H. Chase, G. D. Rosen, & G. F. Sherman (Eds.), Developmen- tal dyslexia: Neural, cognitive, and genetic mechanisms (pp. 41-61). Baltimore, MD: York Press. Prince, R. (1990). Somatic complaint syndrome and depression: The problem of cultural effects on symptomatology. Transcultural Psy- chiatric Research Review, 2, 31-36. Regan, T., & Woods, K. (2000). Teachers’ Understanding of dyslexia. Educational Psychology in Practice, 16, 333-347 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/713666081 Riddick, B. (1995). Dyslexia: Dispelling the myths. Disability and Society, 10, 457-473. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09687599550023453 Shaywitz, B., Shaywitz, S., Pugh, K., Fulbright, R., Mencl, W., Con- stable, R., Skudlarski, P., Fletcher, J., Lyon, G., & Gore, J. (2001). The neurobiology of dyslexia. Clinical Neuroscience Research, 1, 291-299. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1566-2772(01)00015-9 Spencer, K. (2000). Is English a dyslexic language? Dyslexia, 6, 152- 162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0909(200004/06)6:2<152::AID -DYS158>3.0.CO;2-P Snowling, M. (1987). Dyslexia: A Cognitive Developmental Perspec- tive. Oxford: Blackwell. Snowling, M., & Thomson, M. (1991). Dyslexia: Integrating Theory and Practice. London: Whurr. Stein, J. (2001). The magnocelllular theory of developmental dyslexia. Dyslexia, 7, 12-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/dys.186 Terras, M., Thompson, L., & Minnis, H. (2009). Dyslexia and psy- cho-social functioning. Dyslexia, 15, 304-327. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/dys.386 Washburn, E., Joshi, R., & Binks-Cantrell, E. (2011). Teacher know- ledge of basic language concepts and dyslexia. Dyslexia, 17, 165-183. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/dys.426 Wadlington, E., & Wadlington, P. (2005). What educators really be- lieve about dyslexia. Reading Improvement, 42, 16- 37. Open Access 948  A. FURNHAM Open Access 949 Ying, Y. W. (1990). Explanatory models of major depression and im- plications for help seeking among immigrant Chinese-American women. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry, 14, 393-408. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00117563

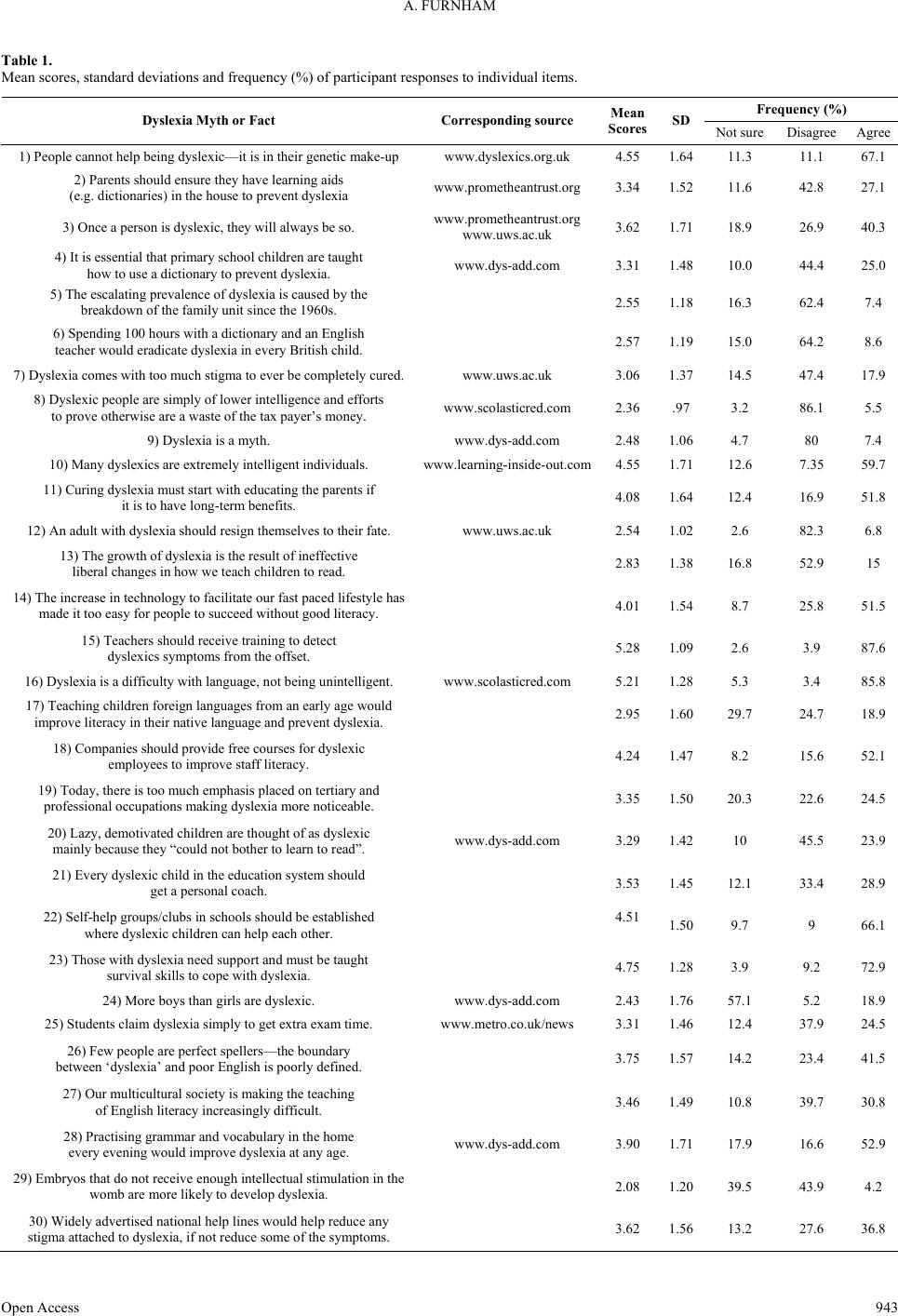

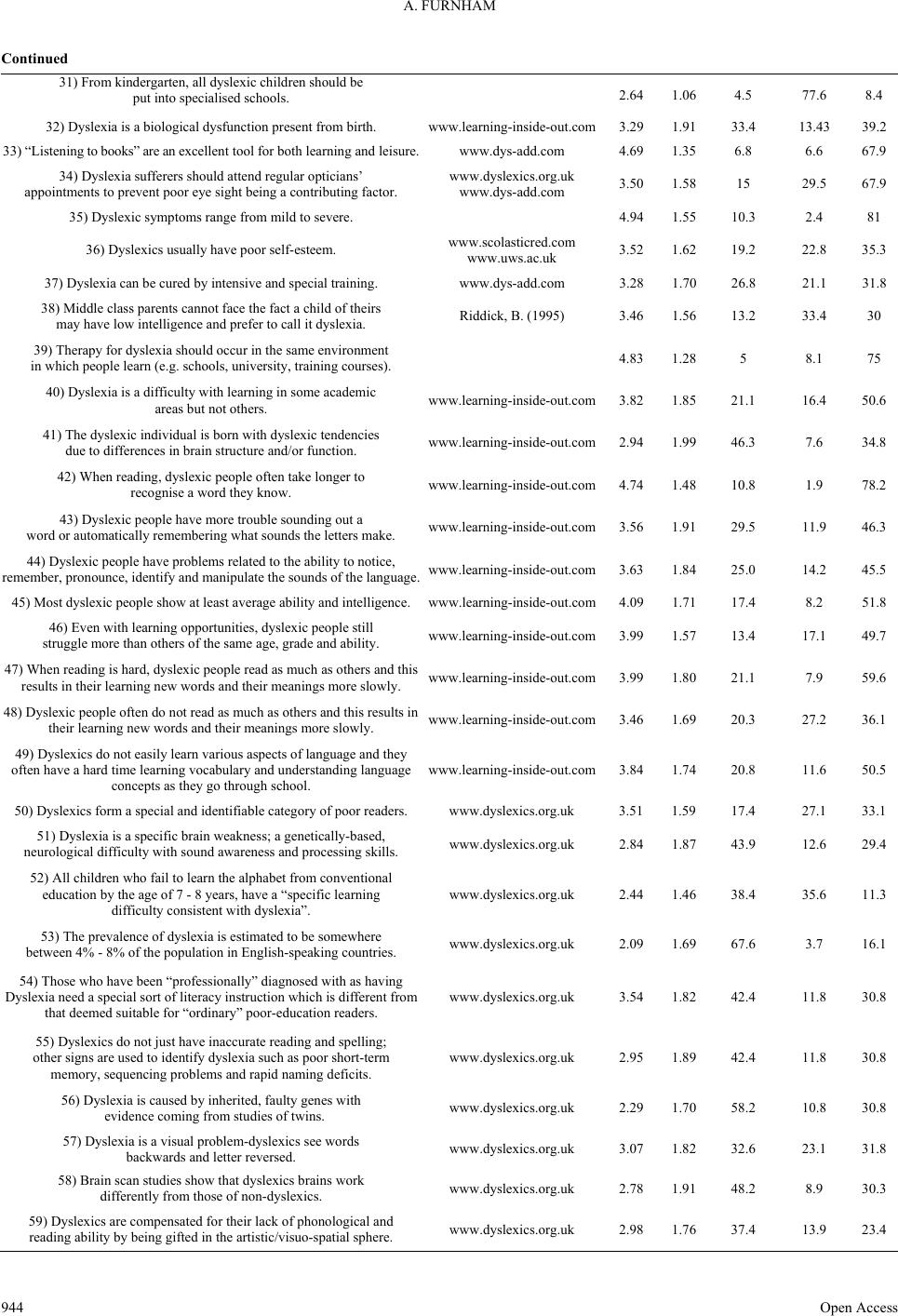

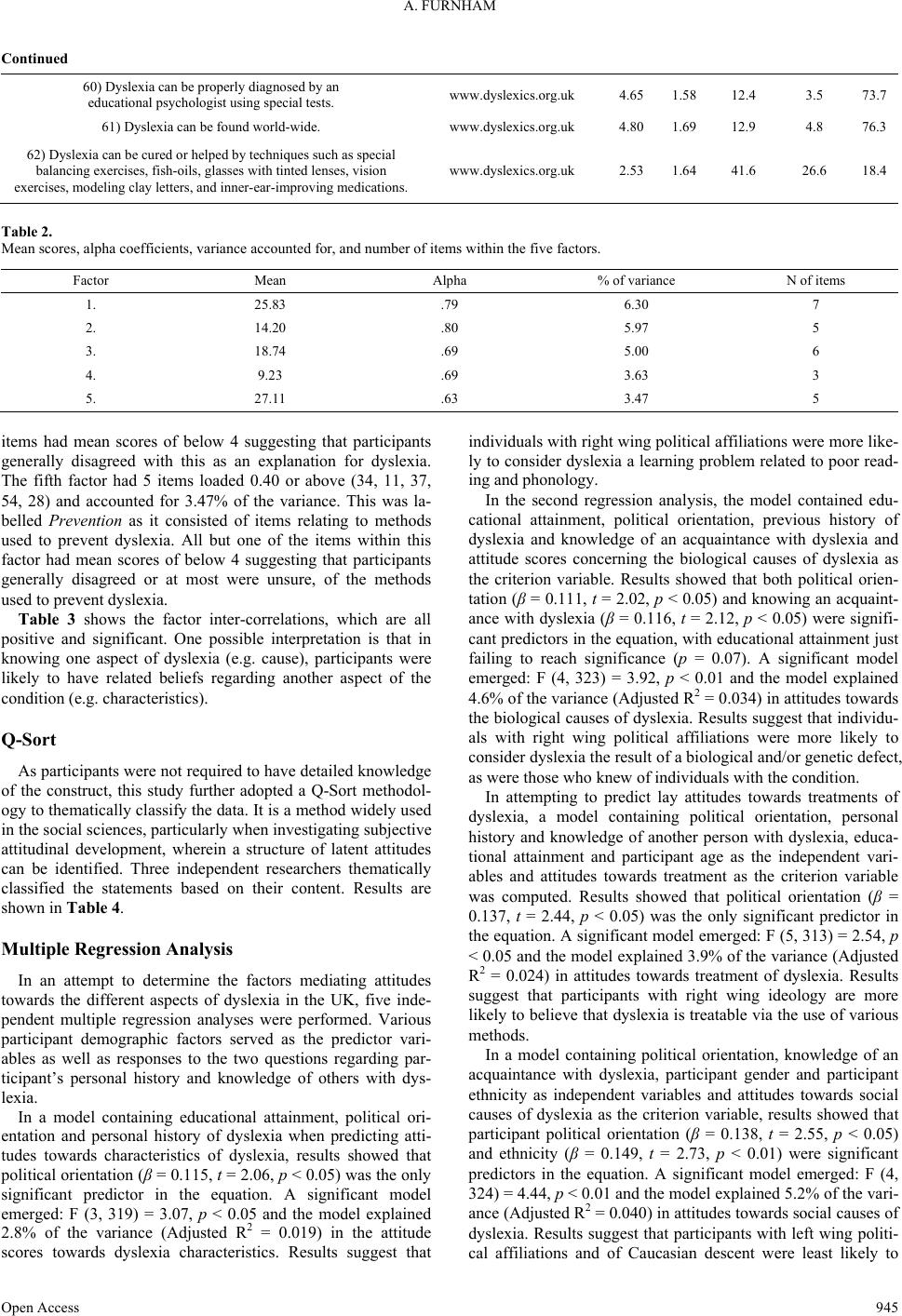

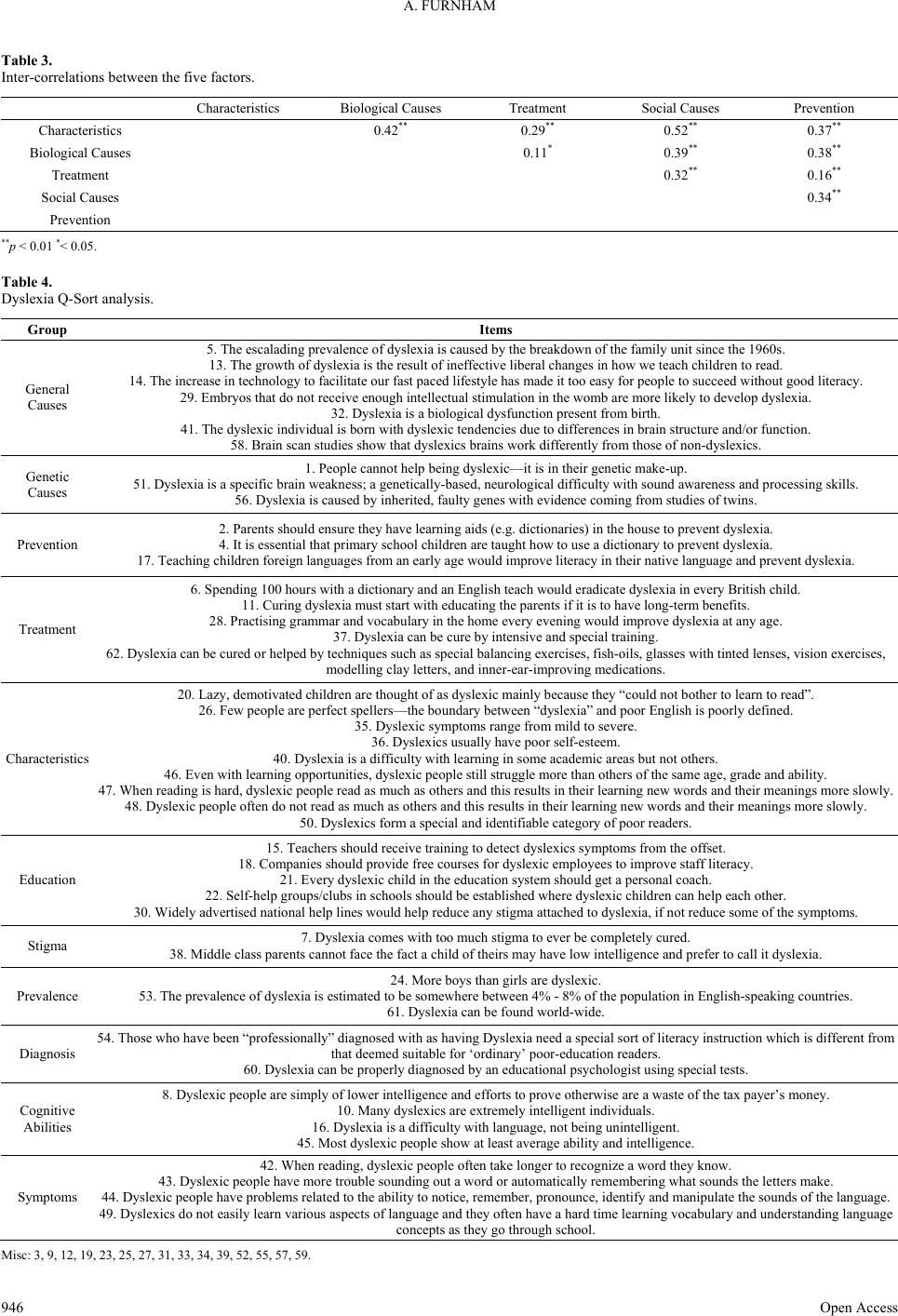

|