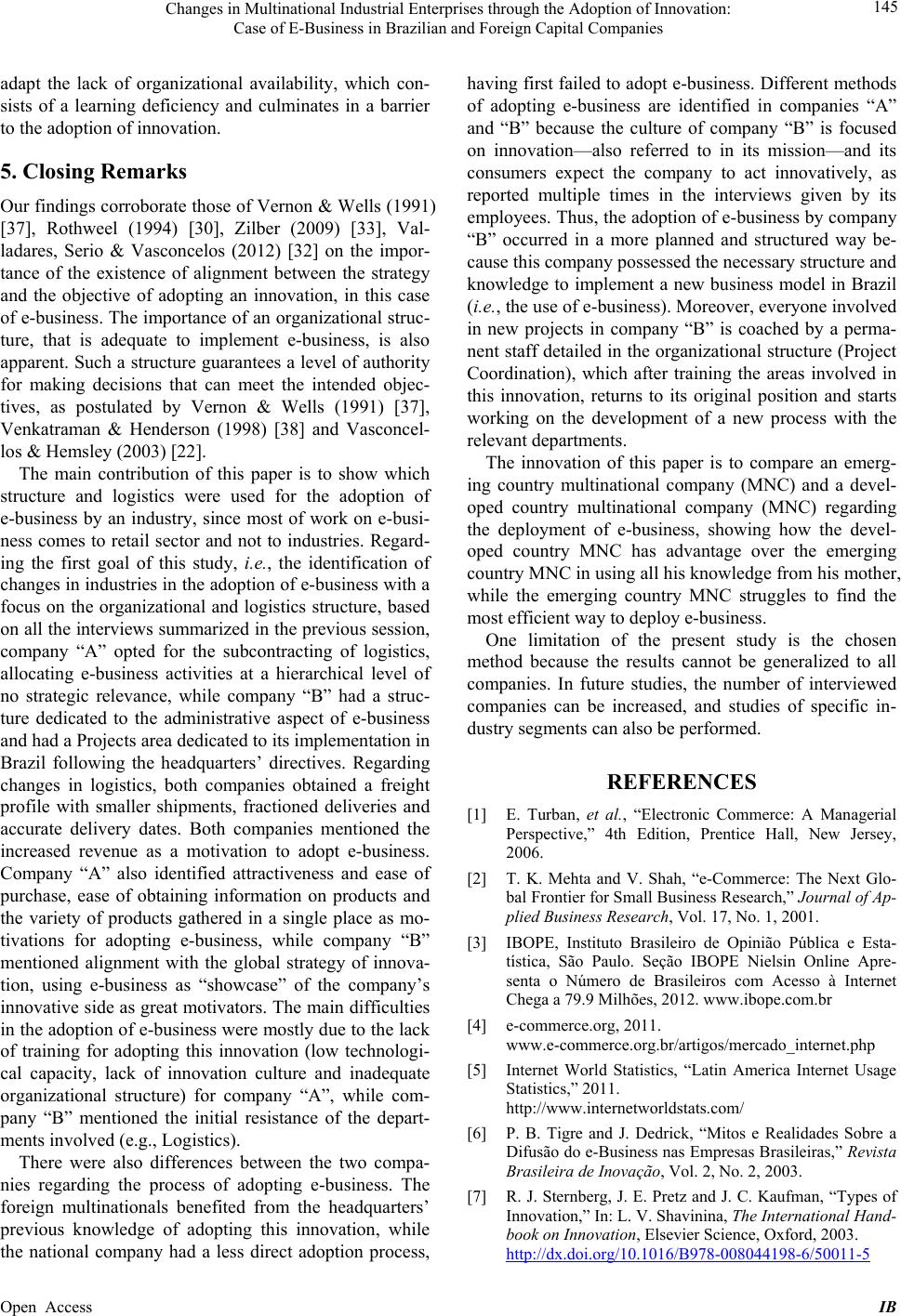

iBusiness, 2013, 5, 136-146 Published Online December 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ib) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ib.2013.54017 Open Access IB Changes in Multinational Industrial Enterprises through the Adoption of Innovation: Case of E-Business in Brazilian and Foreign Capital Companies Silvia Novaes Zilber, Marcelo Scorsato de Rosa Graduate Program in Business, Uninove University, Sao Paulo, Brazil. Email: silviazilber@gmail.com Received June 11th, 2013; revised July 10th, 2013; accepted August 5th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Silvia Novaes Zilber, Marcelo Scorsato de Rosa. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT The objective of this study was to understand the changes that took place in large multinational industries acting in the physical world that, by adoptin g e-business, started acting in the virtual world, as well as the needs that led to this adop - tion. Method: multi-case study with two companies, a national industry (“A”) and a subsidiary of a developed country (“B”) in Brazil. Results: In terms of motivation, both companies mention ed an increase in revenue, but “B” highlighted its alignment with global strategy, focused on innovation and e-business, as a “showcase” of the company’s innovative side. Logistical transformations: “A” hired a logistics operator; “B” developed internally adapted logistics, taking ad- vantage of knowledge from its h eadquarters. Keywords: E-Business Adoption; Multinational Industries; Innovation; Logistics; Organizational Structure 1. Introduction Most large industries established in Brazil have their roots in the “physical world” and did not have activities in the “virtual world” at th e time when the Internet came to be. However, with the advent of the Internet as a busi- ness tool, many companies began to understand that this tool could be a way to further their business, leading companies to adapt their operations to the virtual world and expand their commercial frontiers. Turban et al. (2006) [1] define “e-business” as activi- ties that use the Internet to facilitate the trade (purchase and/or sale) of goods, the provision of services to the consumer, collaboration with commercial partners and the performance of transactions within an organization. One of the great innovations brought about by the Internet was disintermediation. Large industries histori- cally did not directly connect to their end clients and therefore required that middle-men could now make such a connection. Mehta & Shah (2011) [2] identify several reasons to incorporate e-business as a new distribution channel for companies, with particular emphasis on the potential for geographic expansion and greater exposure in current markets. E-business has been growing in recent years. Data from the Brazilian Institute of Public Opinion and Statis- tics (Instituto Brasileiro de Opinião Pública e Estatís- tica)—IBOPE (2012) [3] show that the number of Bra- zilians that access the Internet has reached 79.9 million in the fourth quarter of 2011, an increase of 8% relative to the same period in 2010. Th e website e-commerce.org (2011) [4] states that, in Brazil, online sales clearly tend to increase and that since 2008, the billing of e-business has grown 30% yearly and is expected to maintain this rate over the next three years. The website Internet World Statistics (2011) [5] reports that Brazil currently has 76 million Internet users, a number that has grown 900% since 2000. Tigre & Dederick (2003) [6] state that e-business has become an instrument that is increasingly used by tradi- tional organizations as a means to complement their business. Of the various types of transactions that occur in e-business, perhaps one of the most well-known is business-to-consumer (B2C), i.e., business between com- panies and end consumers, a practice also known as elec- tronic commerce or e-commerce for short. By adopting e-business or, more specifically, e-com-  Changes in Multinational Industrial Enterprises through the Adoption of Innovation: Case of E-Business in Brazilian and Foreign Capital Companies 137 merce, industries establish an innovation process regard- ing the implementation of new ideas in a given context and assume collective interactions (Sternberg; Pretz; Kaufman, 2003) [7]. Porter (2001) [8] states that the is- sue is not whether companies should use the Internet to do business but rather how best to use it if the company is to remain competitive. Regarding achieving this aim, the key challenge is the possession or implementation of an organizational structure capable of handling this de- mand. Many companies in the real world are trying to change their structures to support a virtual business model, as stated by Kalakota & Robinson (2004) [9]. Although there has been considerable study on the subject of retail companies operating in the electronic world, little has been written about industries using B2C as a means to directly contact their end clients. This new operation im- pacts various segments of the company. Once disinter- mediation takes place, tasks that were previously dele- gated to an intermediary, such as delivering products to the end consumer, must now be addressed by the Indus- try itself, which did not have to do this before adopting e-business. When implementing B2C models, industries also need to adapt with respect to merchandise volume, because traditionally, industries sell to distributors and wholesalers, who tend to require large production vol- umes. However, the logistics of an e-business model gen- erally involves small volumes; this transition is a very complex operation for industries that did not previously operate in the virtual world. In this context, the goal of this study was to understand the changes caused by the adoption of e-business or, more specifically, e-commerce (a B2C relationship), in large multinational industries that acted in the physical world and started acting in the virtual world, as well as the needs that led to this adoption. Of the changes that were investigated, the focus was first on those taking place in the organizational structure of the companies under study, given the relevant role of a company’s or- ganization in taking advantage of the opportunities of e-business. Secondly, attention was also given to the transformations that took place in these companies’ lo- gistics because, although the adoption of e-business is associated with significant advances in commercial tran- sactions, according to Barlow et al. (2004) [10], the same does not happen with logistic flow, subjecting B2C con- sumers to new logistic bottlenecks in addition to those that existed in the normal distribution process. To Fuchs & Fleury (2003) [11], fractionating delivery to the B2C client is recognized as one of the greatest challenges to companies, due to both the geographic comprehensive- ness and the obligation to deliver the product directly to the consumers’ house. This study had t he follo wi n g goal s: Identify the needs that led organizations to adopt e-business; Verify the main changes that took place in the logistic processes and the organizational structures of the in- dustries under study due to the adoption of e-business, specifically B2C; Identify the benefits and difficulties stemming from the adoption of e-business. To achieve these goals, two multinational industrial enterprises were studied; one with roots in a developed foreign country that was active in Brazil as subsidiary and another of national orig in that was founded in Brazil. The companies chosen, aside from being high-profile multinationals, have one particularly relevant difference. The national company is a headquarters, while the for- eign multinational is a sub sidiary. These companies were chosen to determine the differences in the adoption of innovation due to either a headquarters or a subsidiary. For the headquarters, e-business is something completely new, while for the subsidiary, e-businessis a roll out be- cause its headquarters has already implemented this process in other countries and therefore has knowledge and experience obtained outside of Brazil. According to Stal & Campanario (2011) [12], the aca- demic interest of national capital in Brazilian multina- tional companies is relatively new, not older than two decades. There are dozens of studies focused on compa- nies of Southeastern Asia but v ery few about Latin Ame- rican companies, further justifying the study of adopting such a Brazilian multinationa l innovation. The following section is a review of the literature used to elaborate the questionnaire and analyze the results obtained. Next, the investigation methods applied in the study are presented, followed by the results and analysis and closing remarks. 2. Literature Review The theoretical foundation for the present study is pre- sented here. First, we describe the concept of e-business, understood as an innovation, and how this innovation is related to the concepts of organizational structure and logistics, followed by the concepts of Brazilian and for- eign multinationals. Turban et al. (2006) [1] observe that the origin of e-business dates back to the 1970s, starting with data transfer, more commonly known as electronic data in- terchange (EDI). These authors claim that new applica- tions followed the initial ones, from stock negotiation to the purchase of flight tickets. Mishra (2010) [13], states that e-business is becoming one of the best ways to do business. However, companies in emerging countries still struggle to develop e-business in a sustainable way and Open Access IB  Changes in Multinational Industrial Enterprises through the Adoption of Innovation: Case of E-Business in Brazilian and Foreign Capital Companies 138 often need to modify their internal structures to promote this innovation. E-business is a fusion of commercial processes, enterprise applications and organizational structure required to create or enhance the traditional model of the company (Kalakota; Robinson, 2004 [9]). In Brazil, e-business initially spread through financial transactions and inside company networks that supported this functionality (Tigre; Dedrick, 2003 [6]). With the widespread use of the Internet, e-business extended its reach to end users, raising companies’ revenues along with the number of consumers using this channel to ac- quire product s and servi ces. Because the adoption of e-business is understood as an innovation for the adopting industry in the present study, it behooves us to define what is meant by innovation and its adoption. Rogers (1995) [14] defines innovation as an idea or object that is identified by the individual as some- thing new. The development process of innovation con- sists of all decisions and activities, as well as their re- spective impact in the event of a necessity or problem, during there search, development and commercialization of an innovation. In the Oslo Manual (OCDE, 2005) [15], innovation is a vision based on knowledge and focused on interactive processes through which knowledge is created and exchanged within and between companies. Tidd, Bessant & Pavitt (2008) [16] define innov ation as a change process driven by the ability to establish rela- tionships, detect opportunities and take advantage of them. These authors divide it into four distinct categories: product, process, position and paradigm innovation. For the present study, one may consider the adoption of e-business as a process innovation. For large industries that operated only in the real world, adopting e-business is an innovation. However, there are obstacles, as noted by Johnson (2010) [17], including risk perception, lack of knowledge, trust and organiza- tional availability. In multinational companies, innovations can be trans- ferred between subsidiary companies, from the head- quarters to subsidiaries and vice-versa. Thus, multina- tionals develop three types of organizational competence capable of contributing to the diffusion of innovation, according to Dunning (1993) [18], as follows: local com- petences, non-local competences and specific compe- tences. Competences are important for the diffusion of innovation among subsidiaries because they enable com- panies to create or adapt innovation to their local envi- ronment. Subsidiaries that adapt innovations transferred from their head quarters are creating local innovation; those that develop innovation but have difficulty trans- ferring it back to the headquarters, or vice-versa, create specific innovations; and finally, subsidiaries that adapt or develop innovations that are later adopted by others are creating non-local innovations. According to Oliveira Jr., Boehe & Borini (2009) [19], the greater the auton- omy of a subsidiary, the greater its decision power and the capacity to develop innovation initiatives are. How- ever, excessive autonomy may hinder the exploitation of internal initiatives by the multinational corporation and may lead to innovation decisions that target diverging objectives, causing a rupture in corporate strategy. Foreign multinationals have well-known brands, in- novation processes tested in other countries, sophisti- cated technologies, efficient management systems, finan- cial resources that do not always have their origin in the host country because they seek lower interest rates and efficient networks of suppliers, distributors and logistics (Khanna; Palepu, 2006 [20]). According to Khanna & Palepu (2006) [20], multinational companies that are developed in emerging nations have institutional defi- ciencies consisting of the lack of efficient innovation systems and regulation, as well as volatile political and economic environments and consumers who, although demanding, are sensitive to prices; an efficient innova- tion management might mitigate such difficulties. In the case of a subsidiary acting in an emerging nation, knowl- edge may be transferred from the headquarters in a de- veloped coun try; knowledge is of particu larly high value, considering that foreign markets grant access to new ideas and stimuli that can be applied in emerging nations where the multinational operates (Oliveira Jr., 200 7 [21]). The comparison between national and foreign multina- tional companies in the domestic markets of emerging nations shows that the former develop competence, sk ills and trust that allo w it to compete with foreig n companies (Stal; Campanario, 2011 [12]), and, as a consequence, it becomes more competitive in the market in which it op- erates. Therefore, the study of these multinationals and their innovations, which can lead to competitive advan- tages, is an important part of the study presented in this article. Regarding the transformations that may occur in the organizational structure of companies that adopt innova- tion, in this case, e-business, Vasconcellos & Hemsley (2003) [22] claim that the speed of change and the in- crease in the complexity of the environment in the last few decades made it necessary to develop structures to effectively respond to these changes. For a long time, a certain set of structural patterns were employed by many kinds of organizations. These structures are defined as the result of a process in which au thority is distributed to activities in all levels, from the lowest to the highest. Responsibilities are specified, and a communication sys- tem is designed to allow people inserted in this structure to perform tasks and exert the authority they have to achieve the company’s objectives (Vasconcellos; Hem- Open Access IB  Changes in Multinational Industrial Enterprises through the Adoption of Innovation: Case of E-Business in Brazilian and Foreign Capital Companies 139 sley, 2003 [22]). In terms of organizational structure, Costa et al. (2010) [23] state that structures without many hierarchical levels that are oriented towards multi- functional teams are better able to adapt to mutating en- vironments that seek innovation. Regarding the impact of the adoption of e-business on the logistics of the adopting companies, Bornia et al. (2006) [24] state that, as a result of this new age of eco- nomics where each Internet access may result in a new purchase, logistics serve e-business as a value-aggregate- ing activity, and companies exploiting this strategy may obtain competitive edges that will allow their survival and grant financial return. Following Coelho & Cristo (2007) [25], B2C e-business requires differentiated logis- tics with particular characteristics that are not tradition- ally available, such as the integration between informa- tion on the availability of a given product on the site (front end) and the actual availability of the said product in stock (back office). In traditional logistics, a material good is thought of as a well-estab lished physical positio n; in virtual logistics, however, what matters is that the product be available when necessary. According to Alves et al. (2005) [26], while traditional logistic systems are developed to serve commerce between companies with orders of large volume, in which most deliveries are made to distribution centers or stores, the logistics of virtual commerce are characterized by a large number of small orders that are geographically spread out and frag- mentally delivered, resulting in low d emographic density and high delivery cost (ALVES et al., 2005 [26]). B2C e-business requires differentiated logistics with particular characteristics that are not provided by traditional logis- tics. True, its logistics do present, in a sense, the same concepts as the traditional ones, but they are adjusted to the specific characteristics of an e-business environment (BORNIA et al., 2006 [24]). Tools that are very similar to those used in traditional logistics are employed here; however, they must be adapted according to the particu- lar traits of the process. The adaptation can be c ons ider ed an innovation for companies that were not founded in a virtual environment but wish to enter this model to ser- vice previously unreachable clients. 3. Investigation Method This study was undertaken with an exploratory aim, is of a qualitative nature, and employed a multiple case study method in which the companies were studied by means of interviews using semi-structured questionn aires, docu- ments made available by the companies and analysis of their websites, thus allowing data triangulation. Vieira (2004) [27] states that qualitative study has been used in some specific fields of study in applied social sciences, and it can be defined as having its main fo undation in th e analysis of qualitative d ata, i.e., it is characterized by not making use of statistical instruments of data analysis. According to Yin (2003) [28], qualitative methods allow the researcher to gain an overview of events within the context of real life, and their use is appropriate in studies that aim to understand complex social phenomena. Given that this study tries to understand, first, the transforma- tions caused by the adoption of e-business, and more specifically, e-commerce (B2C relationship), by large multinational industries that were originally active in the physical world and then started acting in the virtual world, and secondly, the motivations for this adoption, exploratory research of a qualitative nature seemed ap- propriate. The method chosen for this exploratory inves- tigation was the multiple case study, which allowed for acomparison between the companies participating in the study in terms of how they innovated, their different ad- aptation processes and the difficulties encountered while adopting innovatio n. The companies chosen for the study were selected be- cause they are multinational, one from an emerging na- tion (Brazil) and one from a developed country, and also because are both large businesses that sell directly to the consumer through e-business (B2C). These criteria great- ly constrained the scope of this study because there are few industries in Brazil that sell directly to the end client through the Internet. Th e comparison between companies of different origins is pertinent because the aim is to in- vestigate whether the branch office acting in Brazil can benefit from the knowledge obtained from the experi- ences of the headquarters. The companies that were in- terviewed do not belong to the same segment; however, both are characterized by the production of consumer goods and by having their own websites where they sell directly to the end consumer. This choice was made be- cause two multinationals in the same field but of differ- ent capital, i.e., one nationa l and one fo reign, both sellin g their product directly through the Internet, could not be found. Data were gathered through semi-structured inter- views and via examination of documents provided by the company, newspaper and magazine articles, the compa- nies’ websites and academic articles about the companies. Regarding the semi-structured interviews, nine employ- ees of company “A” and eight of company “B” were interviewed; these employees held positions such as Wholesale Director, Marketing Manager, E-business Manager, New Media Communications Manager, Dis- tribution Manager, Transport Manager, Distribution Cen- ter Operator, Supply Chain Manager and New Business Manager, among others. Each interview took approxi- mately one hour, and the subjects were persons desig- nated by the companies themselves as those best quail- fied to help reach the objectives of the present study. Open Access IB  Changes in Multinational Industrial Enterprises through the Adoption of Innovation: Case of E-Business in Brazilian and Foreign Capital Companies 140 Complementary data were obtained later through tele- phone communication and also by e-mail exchange to clarify some details. The analysis of the data consisted ofexamining, categorizing, and classifying or, alterna- tively, recombining the qualitative evidence to meet the end goal of the study. No statistical procedures w ere used to analyze the data because the whole study was grounded on a qualitative approach (Godoy, 2006) [29]. Because this study’s investigation is of exploratory char- acter, there was no intention to establish variable correla- tion. 4. Results and Analyses The obtained results are presented in this section; both companies under study are introduced, and the evidence that was analyzed to reach the proposed objectives is described. 4.1. Implementation of E-Business in Company “A” The national capital company, referred to in this stud y as company “A”, is the largest shoe company in Latin America in terms of units produced, with R$ 3 billion in revenue in 2011, of which R$ 2.5 billion was from the domestic market. It holds 16% of the national shoe mar- ket and 55% of the rubber sandal market. It has 12,000 employees in Brazil and approximately 5000 abroad. Because the company was structured to sell large vol- umes to wholesalers, department stores or retail outlets, it did not have the knowledg e of how to sell directly to the end consumer through e-business. “[...] The company had never before sold directly to the end consumer, and that was a change in our processes [...]”, stated the mar- keting manager. Technical areas, such as Information Technology, had to hire consultants to develop the web- site, and at a later stage, specialized personnel were hired to manage the e-business component. The idea of adopt- ing the e-business system sprung from the company itself and was fully developed in Brazil. The development of the Brazilian website served as a reference for the de- velopment of the online store for the US, Europe and some e-business initiatives in Southern Asia. The com- pany has branches outside of Brazil; however, there was no knowledge transfer from these other units to Brazil. Instead, the Brazilian unit was the head quarters for the institutional develop ment of e-business in its subsidiaries. In the interview, this fact is made evident by the e-busi- ness manager: “[...] we worked together with other com- panies because e-business is a completely new business that normally nobody in an industry fully masters and often, also, in physical retail, it is business-specific”. The project to develop e-business in company “A” started in a planned manner in 2007 and was consoli- dated in 2009, when the company put two brands of its portfolio at the end consumer’s disposal. The develop- ment of e-business as a new channel for the consumer was not a simple task because of the size of the company, which had a large number of departments and personnel involved, in additio n to the lack of sp ecific training in the company to adopt this innovation at the time. Addition- ally, the development of e-business studied here was its second experience in selling products directly to the consumer. The first one occurred in 2005, was not suc- cessful and was abandoned in 2006. The adoption of e-business was attempted again in 2007. The interviews and accounts obtained in the present work refer to the second attempt by company “A” to adopt this type of business in 2007. The development took place in Brazil, but the internal knowledge necessary to promote the de- velopment of e-business was not available because this was a new activity for the company; therefore, technical training was sought by hiring specialized companies. Technical areas such as Information Technology hired consultants to develop the website, and at a later stage, specialized personnel were hired to manage the e-busi- ness. The Brazilian headquarters did not interfere in the op- erational structure (warehousing and distribution) of the e-business in other countries. Therefore, subsidiaries had autonomy to hire locals for these services. The guidelines from the head quarters were focused on visual alignment, product organization and brand appeal (pictures of new products, colors and the company logo), in conformity with the Brazilian website, to guarantee brand preserva- tion. In company “A”, the departments involved in this adoption understood that the objectives of this company behave differently, and further, there was no alignment between the objective of adopting e-business and the company’s strategic objectives. However, during the in- terview process, it was concluded that the true motiva- tion had been to increase sales. The process to develop e-business involved, in itially, sales and marketing execu- tives and, later, information technology executives. The involvement of logistics in the project’s conception and implementation phase was not so markedly present as that of IT, as revealed by the following statements from the transport and distribution managers: “[...] a superfi- cial involvement of logistics”; “[...] we know of the im- portance, but there was no greater involvement of logis- tics due to lack of appropriate knowledge and acknowl- edgement of the project’s importance”. In the organizational structure, the e-business area was allocated to the Retail Board , which is responsib le for the management of franchises and company stores. This Open Access IB  Changes in Multinational Industrial Enterprises through the Adoption of Innovation: Case of E-Business in Brazilian and Foreign Capital Companies 141 board made their brands available for consumers to pur- chase through the Internet because this was a new area, and the company itself was not certain which board would be responsible for the management of e-business. One interviewee from retail said that a more appropriate place for e-business within the company was missing, i.e., company “A” did not have a specifically prepared area for this type of business and thus made use of the exist- ing structures. There was no consensus regarding the necessity of conceiving an e-business project. Interview- ees from sales and marketing admitted that the develop- ment had its origins in their areas: “[...] everything started in sales and marketing [...]” or “[...] they [sales and marketing] had the idea of organizing the products and making them available through the Internet [...]”. Thus, it is apparent that the true motivations underlying adopting innovation were confounded, and there is no certainty as to what motivated this adoption. The information gathered from interviewees from company “A” diverges on the necessity of adopting e- business. Data obtained in this study show that the com- pany acted “in an amateur fashion and without a clear objective” that would justify the development and im- plementation of e-business, as reported by some e-busi- ness, company stores and sales managers. Some of the e-business objectives, as stated in these interviews, are as follows: [...] “a differentiated status for the product, with a so- phisticated flair”. [...] “the opportunity forbrands in a field that grows, say, around two digits every year ”. [...] “the goal is to make a mix of products available to the consumer thatis hard to find in the common store”. [...] “to make it easier to purchase, and provide a place where people can research information about the prod- ucts”. In its second attempt to implement e-bu siness in 2007, the organizational structure of the logistics of company “A” was called “Distribution” and was placed under the Supply Chain Board. Along with Logistics, the field of Planning was subordinate to this Board. The company justified placing logistics (i.e ., distribution) under the same management because both pertain to the same chain of operations. In 2009, the cost to process orders from e-business was lower than that of traditional orders, even though the shipping cost was higher. The logistic flow to process an order proved to be advantageous when compared to the costs of maintaining a physical store, which has additional costs, such as employees, rent, taxes, water, electric power and building maintenance, etc. Although they do not have physical contact with the product, consumers utilizing the e-business model have greater variety at their disposal, and in general, products cost less. Logistics, despite their importance and role as a strategic area for the success of activities related to this channel, had only superficial involvement in the process because the company opted to subcontract the logistic activities relevant to e-business, hiring a logistics opera- tor to perform the warehousing, distribution and ship- ment of orders. The reason given for this subcontracting acknowledged that logistic operations for e-business are completely different from what the company already had in terms of shipment size. This was confirmed by means of an interview fragment stating “[...] the logistic process is completely different from that of a normal sto re or of a company’s shipment’s and the operator we hired had the required knowledge”. The interviewees in the fields of Marketing and Logistics stated that clients started re- ceiving their orders faster, and in addition, they empha- sized that the service provided by the subcontracted op- erator is one of the best in the country in terms both of punctuality and product quality, i.e., the condition of the merchandise at the moment of delivery. 4.2. Adoption of E-Business in Company “B” Foreign capital company “B”, founded in 1919 in Swe- den, is a current global leader in electrical household appliances, selling over 55 million units per year in over 150 countries. The company focuses on product innova- tion based on extensive opinion polling to determine the real needs of consumers. Oriented towards product and process innovation, it adopted B2C in 2004 without the intent to significantly increase revenue; instead, the company aimed to imple- ment an innovation in Brazil that was already common practice in other countries, such as Italy. Thus, the main objective of adopting e-business was the alignment of the branch office’s objectives with the company’s global strategy, so that all countries shared the same processes and procedures, giving the headquarters greater control over its global operations. However, at the end of the implementation, they also gained commercial insight into e-business, similar to company “A”. In the last three years, the process was considered to be consolidated by company “B” after a period of transformations in IT (In- formatio n Te ch no log y) an d Log istic s, ar e as co n sid e r ed to be essential to and responsible for the high performance demanded by consumers that favor the e-business chan- nel to acquire their products. Company “B” sees the adoption of innovation as something of extreme importance, reflected in are mark by the distribution center’s operator: “[...] innovation is ‘in the blood’ of the company [...]”. It is part of the com- pany’s mission to provide innovative products beyond consumers’ expectations. However, even if the search for innovation is part of the company’s mission, the Brazil- Open Access IB  Changes in Multinational Industrial Enterprises through the Adoption of Innovation: Case of E-Business in Brazilian and Foreign Capital Companies 142 ian branch resisted the adoption of e-business (under- stood as innovation) because, at first, this was not an opportunity to increase sales but rather a model “sug- gested” by the headquarters to promote a global align- ment with the operations in other countries. Regarding organizational structure, the Brazilian branch of company “B” consists of five boards. Supply Chain and Sales are responsible for Logistics and E-Business. The Projects area, physically located in Curitiba (PR), is subordinate to the Supply Chain Board; this area is re- sponsible for the development of new processes or pro- cedures that originate from the headquarters or are ideal- ized in the subsidiary itself. Company “B” planned to adopt e-business, and the Project Coordination area, re- sponsible for the development and implementation of innovations originating from the headquarters, coordi- nated the whole process. After implementation, the pro- fessionals who were part of this coordination area were no longer part of the e-business staff and returned to the project area to work on development demands. As stated by the projects and new business manager: “[...] the company adopted this condition and invested because there is a culture of structured innova tion, and it does not consider chance [...]”. Interviewees stated that there was no change in the fi- nal design for e-business implementation as proposed by the Brazilian branch because the headquarters approved of and trusted the professionals who were responsible for the execution. These professionals consisted of a multid- isciplinary team from the project and e-business areas. Company “B” thus implemented this electronic sales channel with a local team without having to hire third parties or consultants but instead involved all areas, such as logistics, finance and information technology, pre- serving the local traits of the country. Company “B” at- tributes a good deal of the success in this implementation to the support given by HR to the people who were in- volved in and affected by the innovation and the use of e-business. The company’s Logistics achieved national coverage, with a strong concentration in the So utheast. This is to be expected given that the main clients, large retailers, are concentrated in this region. With six companies shipping their products, company “B” acquired relevant experi- ence in delivering large volumes concentrated in a few clients, and until the start of the e-busin ess project, it did not ship directly to the end consumer. The internal opera- tional structure is the same for the logistics of e-business as for the traditional one, i.e., the logistics personnel of company “B” share the management of both channels. This situation is identical to wh at is found in distribution centers, cargo aggregators and transportation companies, according to accounts of interviewees from the e-com- merce and logistics areas. The first transformation to take place, as identified by the company, was the delivery of small shipments, which spiked in amount and number of destinations. As a result, the company looked for trans- portation companies that were more fractional-load ori- ented (small shipments) and specialized in e-business. Another change perceived by company “B” was that e-business customers are more demanding in regard to delivery punctuality. Table 1 presents a synthesis of the main results found during the study conducted on companies “A” and “B”, classified according to the analysis categories identified by the content assessment. The table below was obtained from the analysis of the speech of all respondents, iden- tifying in these discourses possible categories (or labels) that best translate into the language of business that has been said by the respondent managers. Therefore, the answers about the process of adoption of e-business by companies can be summarized by the following groups or categories of findings: needs that led to e-business implementation; difficulties in adop ting e-busin ess; bene- fits brought about by the adoption of e-business; trans- formations in logistics; transformations in organizational structure; process of knowledge transference from the headquarters to its subsidiaries regarding the implemen- tation of e-business; commitment to innovation; and alignment with the strategic objective. 4.3. Analysis of Results For the analysis of the results, in addition to the primary data obtained, we use a comprehensive literature review to support the findings of this research to compare what was found with what is established in the literature cited, thus, we can ensure that the analysis made is based in a theoretical framework that make sour conclusions be more robust. For Rothwell (1994) [30], Ahmed (1998) [31], Val- ladares, Serio & Vasconcellos (2012) [32] and Zilber (2009) [33], there must be a strategic objective that “guides” innovation within a company. This objective is not clear for company “A”, and there is also no align- ment between strategy and e-business because the execu- tives never give an indication that e-busin ess is su ppo rted by a strategy defined by the headquarters. In company “B”, a foreign multinational and subsidiary of its head- quarters, the adoption of e-business was done in align- ment with the overall strategy; in 2 0 04, this multinatio n al sought to standardize management models across all ar- eas of its subsidiaries, so that they would have identical processes, and therefore, headquarters would have better control of the branches. According to Tidd, Bessant & Pavitt (2008) [16], developing new processes constitutes one of the ways companies innovate. This was observed Open Access IB  Changes in Multinational Industrial Enterprises through the Adoption of Innovation: Case of E-Business in Brazilian and Foreign Capital Companies Open Access IB 143 Table 1. Synthesis of categor ies found in the study. Category of findings Company “A” Company “B” Increase in revenue. Alignment with global strategy, focused on i nn ovation. Channel seen by the consumer as innovative. Increase in revenue. Attractiveness and ease of purchase. Easy way to obtain infor mation about products. Needs that led to e-business implementation Variety of products gathered in a single place. Focus in innovation; e-business as “showcase” of the company’s innovative facet. Lack of knowledge to develop the new sales channel.Non-commercial project. Low technological level. Resistance from departments involved, e.g., logistics. Lack of an innovation culture. Risk of post-implementation failure. Difficulties in adopting e-business Inadequate organizational structure. Reduced cost to process an order. Refined criteria for hiring third part ies to deliver produc ts. Removal of intermediaries . Benefits brought by the adoption of e-business Greater assortment of pr oduct s made available to the consumer. Exposition of products without resorting to a ph ysical structure. Cargo profile: small shipments. Fractioned deliveries. Assertive delivery dates. Employment of th i rd party to operate logistics. Same interna l t e am for traditional business and e-business. Autonomy to ship orders (e.g.: prioritizing e-b u s i n e s s o rders). Changes in logistics Lower logistics cost. Hiring of transportation companies with differentiated, specialized profile. Shared structure for e-business in administrative aspects because the operational structure is dedicated to hiring third-parties. Dedicated structure for e-business in administrative aspects because the operational structure is shared. Structure out of strategic focus. Structure based in foreign subsidiaries. In Brazil, it is an autonomous structure, but its innovations must be validated by the headquarters. Changes in organizational structure Lack of hierarchical importance for e-business because the company allocated it to the retail board without strategic grounds. Stable structure; the area was not shifted to another board because e-busines s was given hierarchical importance. Process of knowledge transference from the headquarters to its subsidiaries, regarding implementation of e-business The headquarters could not help its subsidiaries very much because it lacked knowledge of e-business. At most it provided its opinion on some issues, e.g. layout of products in the website. The headquarters, by means of Project Coordinati on, provided the subsidiary with all information necessary to imple ment e-business b as e d i n previous knowledge and experiences. No innovation management. The company’s mission is to innovate. It is not part of the company’s mission to promote and maintain innovation. Innovation is present at all levels of the company. Little commitment from the board. There are well-defined processes for managing innovation. Commitment to innovation Disorganized processes. Dedicated staff area for impleme nting innovations. Indeterminate objectives in adopting e-bus iness.Global alignment with the operations in other coun tries where the company already operates e-business. Low priority for the project. Met the expectations of clients to be constantly innovating. Project initiated in departments and not by a board directive. Alignment with strategic objectives Strategic planning without impact. Fulfilled the objective of strategic alignment proposed by the headquarters. Adaptation of organizational structure. Standar dization of headquarters and subsidiaries. Hiring of more efficient service providers. Success in implementing the company’s strategies. Main results obtained b y using e-business Deliveries with better level of service (punctuality and quality o f p r o du c t ). Commercial expansion.  Changes in Multinational Industrial Enterprises through the Adoption of Innovation: Case of E-Business in Brazilian and Foreign Capital Companies 144 in this study, where both companies developed a change process to take advantage of a perceived business oppor- tunity, in this case, e-business, allowing for increased sales in their markets, independent of the needs that drove them to innovation. Company “A” did not show a capacity for innovation, as evidenced by the lack of trained professionals that could elaborate and implement a n ew project outlined by the company as an objective. Ahmed (1998) [31] asserts that, for a company to innovate, the qualifications of its executives are fundamental because they enable the ful- fillment of the plans. The hiring of third parties by com- pany “A” (logistics operator) capable of serving the e-business to meet delivery dates and provide warehous- ing corroborates the findings of Kalakota & Robinson (2004) [9], who emphasize the need to hire third parties to plan and execute projects when a company cannot do everything perfectly and/or there is a lack of technical preparation by the executives, with the intention of in- creasing efficiency and reducing costs. In company “B”, the culture of innovation is evident because it has an organizational structure oriented toward innovation that encourage sinter actions with other areas, which contributed to the success of the project. The Bra- zilian subsidiary received knowledge transferred from the headquarters, which had already implemented the same e-business project in other countries; therefore, the adoption of e-business occurred in a planned and organ- ized fashion, involving a department called Project Co- ordination, which received and processed all information and brought the right people into the project. The whole innovation process of company “B” was guided by the knowledge and experience of the headquarters and was transferred to the Brazilian subsidiary, in accordance with what Oliveira Júnior (2007) [21] states about the importance of knowledge transfer between headquarters and subsidiaries. Reg arding the autonomy granted by the headquarters to its subsidiaries for innovation, company “A” did not differ from company “B”, a multinatio nal of foreign capital. This corrobo rates the findings of Oliv eira, Boehe & Borini (2009) [19], who report that there is no difference between the autonomy given by multinational companies of either national or foreign capital and that autonomy is linked to bo th the time that the subsidiary is in operation and some strategic functions. Regarding the organizational structure of company “B”, transformations took place to better serve e-business because, according to Vasconcellos & Hemsley (2003) [22], the speed and changes in the environment in which companies operate force them to develop adequate structures for this elec- tronic sales channel. Amabile et al. (1996) [34] suggest that the organizational structure does not impede man- agement allocation but makes it more difficult to inno- vate and, later, improve. Because of this, company “A” takes longer to adapt and, in the future, may be hindered in making improvements. The development process of e-business in company “B” was supported from the start by the subsidiary’s board as well as by the headquarters, where the issue was first discussed. Zilber (2009) [33], states that the involvement of high-level ad ministratio n is fundamental to success, bringing strategic weight to the dedication to the project. However, in company “A”, the origin of e-business was not the board of directors, but the managerial level of the sales and marketing areas, giving the project an image of low priority throughout the company, or what Roth well (1994) [30], denotes as lack of strategic backing, and demonstrates that company “A” lacked attitudes that assured its commitment to in- novation. This is in contrast to company “B”, where a specific department was responsible for the e-business implementation project and managed it from the begin- ning (Project Coordination). Once the project had been implemented, e-business management was elevated to the managerial level. With regard to autonomy, the headquarters of company “B” gave total freedom to its subsidiary to modify its organizational structure. How- ever, this freedom was limited, and headquarters’ ap- proval was needed. Oliveira, Boehe & Borini (2009) [19], state that the autonomy given to subsidiaries is connected to strategic issues, and therefore, the headquarters of company “B”, despite approving its subsidiary’s whole project, also approved every step of the project because it was an important global strategy for the corporation. Regarding approval from the headquarters, a similar process occurred in company “A” because the headquar- ters granted its subsidiaries autonomy in operational is- sues but not in the conception of innovation. In the present stud y, logistics was the key po int for the success of e-business for both companies. Bornia, Don- adel & Lorandi (2006) [24], highlight the importance of logistics as a value-aggregating activity in supporting e-business, allowing a company to survive. Clearly, com- panies that adopted this sales channel needed to modify their logistics processes to better serve e-business. The logistics of company “B” went through transformations due to the unique characteristics of e-business, starting with the issue of shipments and deliveries that decreased in size, increased in number and were delivered to the houses of end consumers. This transformation was fore- seen by Alves et al. (2005) [26], Fleury & Monteiro (2004) [35], and Bayles & Bathias (2000) [36 ], who state that traditional logistics systems are oriented towards large volumes and centralized deliveries. Conversely, company “A” did not adapt, opting to hire a logistics operator that had the necessary skills to coordinateits e-business. Johnson (2010) [17] calls this inability to Open Access IB  Changes in Multinational Industrial Enterprises through the Adoption of Innovation: Case of E-Business in Brazilian and Foreign Capital Companies 145 adapt the lack of organizational availability, which con- sists of a learning deficiency and culminates in a barrier to the adoption of innovation. 5. Closing Remarks Our finding s corroborate those of Vern on & Wells (1991) [37], Rothweel (1994) [30], Zilber (2009) [33], Val- ladares, Serio & Vasconcelos (2012) [32] on the impor- tance of the existence of alignment between the strategy and the objective of adopting an innovation, in this case of e-business. The importance of an organizational struc- ture, that is adequate to implement e-business, is also apparent. Such a structure guarantees a level of authority for making decisions that can meet the intended objec- tives, as postulated by Vernon & Wells (1991) [37], Venkatraman & Henderson (1998) [38] and Vasconcel- los & Hemsley (2003) [22]. The main contribution of this paper is to show which structure and logistics were used for the adoption of e-business by an industry, since most of work on e-busi- ness comes to retail sector and not to industries. Regard- ing the first goal of this study, i.e., the identification of changes in industries in th e adoption of e-busin ess with a focus on the organizational and logistics structure, based on all the interviews summarized in the previo us session, company “A” opted for the subcontracting of logistics, allocating e-business activities at a hierarchical level of no strategic relevance, while company “B” had a struc- ture dedicated to the administrative aspect of e-business and had a Projects area dedicated to its implementation in Brazil following the headquarters’ directives. Regarding changes in logistics, both companies obtained a freight profile with smaller shipments, fractioned deliveries and accurate delivery dates. Both companies mentioned the increased revenue as a motivation to adopt e-business. Company “A” also identified attractiveness and ease of purchase, ease of obtaining information on products and the variety of products gathered in a single place as mo- tivations for adopting e-business, while company “B” mentioned alignment with the global strategy of innova- tion, using e-business as “showcase” of the company’s innovative side as great motivato rs. The main difficulties in the adoption o f e-business were mostly due to the lack of training for adopting this innovation (low technologi- cal capacity, lack of innovation culture and inadequate organizational structure) for company “A”, while com- pany “B” mentioned the initial resistance of the depart- ments involved (e.g., Logistics). There were also differences between the two compa- nies regarding the process of adopting e-business. The foreign multinationals benefited from the headquarters’ previous knowledge of adopting this innovation, while the national company had a less direct adoption process, having first failed to adopt e-business. Different methods of adopting e-business are identified in companies “A” and “B” because the culture of company “B” is focused on innovation—also referred to in its mission—and its consumers expect the company to act innovatively, as reported multiple times in the interviews given by its employees. Thus, the adoption of e-business by company “B” occurred in a more planned and structured way be- cause this company possessed the necessary structure and knowledge to implement a new business model in Brazil (i.e., the use of e-business). Moreover, everyone involved in new projects in company “B” is coached by a perma- nent staff detailed in the organizational structure (Project Coordination), which after training the areas involved in this innovation, returns to its original position and starts working on the development of a new process with the relevant departments. The innovation of this paper is to compare an emerg- ing country multinational company (MNC) and a devel- oped country multinational company (MNC) regarding the deployment of e-business, showing how the devel- oped country MNC has advantage over the emerging country MNC in using all h is knowledg e from h is mother , while the emerging country MNC struggles to find the most efficient way to deploy e-business. One limitation of the present study is the chosen method because the results cannot be generalized to all companies. In future studies, the number of interviewed companies can be increased, and studies of specific in- dustry segments can also be performed. REFERENCES [1] E. Turban, et al., “Electronic Commerce: A Managerial Perspective,” 4th Edition, Prentice Hall, New Jersey, 2006. [2] T. K. Mehta and V. Shah, “e-Commerce: The Next Glo- bal Frontier for Small Business Research,” Journal of Ap- plied Business Research, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2001. [3] IBOPE, Instituto Brasileiro de Opinião Pública e Esta- tística, São Paulo. Seção IBOPE Nielsin Online Apre- senta o Número de Brasileiros com Acesso à Internet Chega a 79.9 Milhões, 2012. www.ibope.com.br [4] e-commerce.org, 2011. www.e-commerce.org.br/artigos/mercado_internet.php [5] Internet World Statistics, “Latin America Internet Usage Statistics,” 2011. http://www.internetworldstats.com/ [6] P. B. Tigre and J. Dedrick, “Mitos e Realidades Sobre a Difusão do e-Business nas Empresas Brasileiras,” Revista Brasileira de Inovação, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2003. [7] R. J. Sternberg, J. E. Pretz and J. C. Kaufman, “Types of Innovation,” In: L. V. Shavinina, The International Hand- book on Innovation, Elsevier Science, Oxford, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-008044198-6/50011-5 Open Access IB  Changes in Multinational Industrial Enterprises through the Adoption of Innovation: Case of E-Business in Brazilian and Foreign Capital Companies Open Access IB 146 [8] M. Porter, “Strategy and the Internet,” Havard Business Review, Boston, 2001. [9] R. Kalakota and M. Robinson, “E-Business: Estratégias para Alcançar o Sucesso no Mundo Digital,” 2nd Edition, Bookman, Porto Alegre, 2004. [10] A. K. F. Barlow, N. Q. Siddiqui and M. Mannion, “De- velopments in Information and Communication Tech- nologies for Retail Marketing Channels,” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, Vol. 32, No. 3, 2004, pp. 157-163. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09590550410524948 [11] A. G. P. Fuchs and P. F. Fleury, “Evolução das Práticas Logísticas do B2C Brasileiro: Um Estudo de Caso,” In: Encontro Anpad, Atibaia, 2003. [12] E. Stal and M. A. Campanario, “Empresas Multinacionais de Países Emergentes—O Crescimento das Multilatinas,” Revista Inteligência, São Paulo, Vol. 1, No. 3, 2011. [13] S. Mishra, “Web Aggregation in India: e-Business Mod- els in New Economy,” Journal Business and Emerging Markets, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2010, pp. 252-266. [14] E. M. Rogers, “Diffusion of Innovations,” 4th Edition, The Free Press, New York, 1995. [15] OCDE, “Manual de Oslo 2005—Organização para Co- operação e Desenvolvimento Econômico,” 2005. http://www.pucrs.br/raiar/prime/download/manual_de_os lo-3ed.pdf [16] J. Tidd, J. Bessant and K. Pavitt, “Gestão da Inovação,” 3rd Edition, Bookman, São Paulo, 2008. [17] M. Johnson, “Barriers to Innovation Adoption: A Study of e-Markets. Technology Management Research Group,” The Open University, Milton Keynes, 2010. [18] J. Dunning, “Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy,” Addison-Wesley, Workhingan, 1993. [19] M. M. Oliveira Jr., M. Boehe and F. M. Borini, “Estraté- gia e Inovação em Corporações Multinacionais: A Trans- formação das Subsidiárias Brasileiras,” Saraiva, São Paulo, 2009. [20] T. Khanna and K. Palepu, “Emerging Giants: Building World-Class Companies in Developing Countries,” Har- vard Business Review, October 2006. [21] M. M. Oliveira Jr., “Transferência de Conhecimento e o Papel das Subsidiárias em Corporações Multinacionais Brasileiras,” In: M. T. L. Fleury and A. Flerury, Inter- nacionalização e os Países Emergentes, Altas, São Paulo, 2007. [22] E. Vasconcellos and J. Hemsley, “Estrutura das Organi- zações,” Editora Pioneira, São Paulo, 2003. [23] R. M. Costa, P. L. Melo, M. V. Cardoso and C. E. C. Ferreira, “Ambiente Interno para Inovação em uma Em- presa de e-Commerce: O Caso Net Flores,” XIII Se- mead—Seminário em Administração, FEA-USP, São Paulo, 2010. [24] A. C. Bornia, C. M. Donadel and J. A. Lorandi, “A Logística do Comércio Eletrônico,” ENEGEP, Brasil, 2006. [25] L. C. Coelho and R. L. Cristo, “A Gestão da Cadeia de Suprimentos Utilizando Conceitos de Logística Virtual,” In: Seget—Simpósio De Excelência Em Gestão E Tecn- ologia, SEGET, Resende, 2007. [26] C. S. Alves, et al., “A Importância da Logística para o e-Commerce: O Exemplo da Amazon.com,” 2005. http://www.congressousp.fipecafi.org/artigos12004/an_re sumo.asp?cod_trabalho=375 [27] M. M. F. Vieira and D. M. Zoua in, “Pesquisa Qualitativa em Administração,” FGV, Rio de Janeiro, 2004. [28] R. K. Yin, “Estudo de Caso: Planejamento e Métodos,” 3rd Edition, Bookman, São Paulo, 2003. [29] A. S. Godoy, “Estudo de caso Qualitativo,” In: C. K. Godoi, R. Bandeira-de-Mello and A. B. Silva, “Pesquisa Qualitativa em Estudos Organizacionais: Paradigmas, Estratégias e Métodos,” Saraiva, São Paulo, 2006. [30] R. Rothwell, “Towards the Fifth-Generation Innovation Process,” International Marketing Review, Vol. 11, No. 1, 1994, pp. 7-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02651339410057491 [31] P. K. Ahmed, “Benchmarking Innovation Best Practice,” An International Journal, Benchmarking, 1998. [32] P. S. D. A. Valladares, L. C. D. Serio and Vasconcellos, “Capacidade de Inovação: Revisão Sistemática da Liter- atura,” XXXVI Anpad Rio de Janeiro, 2012. [33] S. N. Zilber, “Strategic Use of the Internet and e-Business: the ‘Celta’ Case at GM Brazil,” International Journal of Information Technology and Management, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2009, pp. 85-106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1504/IJITM.2009.022272 [34] T. M. Amabile, R. Conti, H. Coon, J. Lazenby and M. Herron, “Assessing the Work Environment for Creativ- ity,” The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 39, No. 5, 1996, pp. 1154-1184. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/256995 [35] P. F. Fleury, “O Desafio Logístico do e-Commerce,” 2004. http://www.ilos.com.br/web/index.php?option=com_cont ent&view=article&id=1006%3Aartigos-o-desafio-logistic o-do-e-commerce&catid=4&Itemid=182&lang=br [36] D. L. Bayles and H. Bhatia, “E-Commerce Logistics & Fulfillment: Delivering the Goods,” Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, 2000. [37] R. Vernon and L. T. Wells Jr., “The Manager in the In- ternational Economy,” Prentice Hall, New York, 1991. [38] M. Venkatraman and J. C. Henderson, “Real Strategies for Virtual Organizing,” MIT Sloan Management Review, Vol. 40, No. 1, 1998.

|