Surgical Science, 2013, 4, 525-529 Published Online December 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ss) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ss.2013.412102 Open Access SS Traumatic Splenic Injuries in Khartoum, Sudan Isameldin O. Ibrahim1, Aamir A. Hamza2*, M. E. Ahmed3 1Department of Surgery, Omdurman Teaching Hospital, Khartoum, Sudan 2Department of Surgery, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahri University, Khartoum, Sudan 3Department of General Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Khartoum University, Khartoum, Sudan Email: *aamirhamzza@yahoo.co.uk Received October 28, 2013; revised November 20, 2013; accepted November 27, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Isameldin O. Ibrahim et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2013 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Isameldin O. Ibrahim et al. All Copyright © 2013 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. ABSTRACT Background: Spleen injuries are most commonly associated with blunt abdominal trauma and represent a potentially life-threatening cond ition. Objectives: To study th e pattern of splenic injuries of the p atient, managemen t instituted an d its outcome at Khartoum. Patients and Methods: This is a prospective, analytic and hospital-b ased multicenteric study, conducted at the three main Teaching hospitals at Khartoum. The study was carried over a period from April 2012 to February 2013. It includes all patients, diagnosed as traumatic splenic injury. Excluded were patients with history of splenic disease, iatrogenic injury or spontaneous rupture. Results: The study included 47 patients: their mean age was 26.4 years (SD ± 14.5). Most of them 41 (87.2%) were in the first four decades of life. Males were predominant 41 (87.2%), with a male to female ratio of 6.8:1. The majority of our patients had blunt abdominal trauma 39 (83%), of whom, road traffic accident accounted for 51.1% and none reported cases of gunshot. Isolated splenic injury was found in 23 (48.9%), and Haemodynamic stability was seen in 27 (57.4%) on presentation. The initial haemoglobin assess- ment revealed <9 gram/dl in 53.2%. CT scan was performed to 24 (51.1%), of whom 66 patients were Grade I and II and none of our patients were diagnosed as Grade V. Blood transfusion was required in 42 (89.4%). Operative treatment was adopted in 66% (61.7% total splenectomy and 4.3% splenorrhaphy), while selective non-operative management was successful in 16 (34%) of the patients. Higher intra-operative grade of splenic injury was found to be significantly associated with blunt abdominal trauma, haemodynamic instability and associated intra-abdominal in juries. 44 patients (93.6%) were discharged home in a general good condition . The morbid ity and mortality were seen in 8.5% and 6.4% re- spectively. Conclusion: Splenic injuries usually follow blunt abdominal trauma, particularly after road traffic accidents. It is common during the first four decades of life with males being frequently affected. The great success rate of adopt- ing selective non-operative management is worthwhile. Keywords: Blunt Splenic Trauma; Nonoperative Management; Splenectomy; Splenic Injury 1. Introduction The incidence of splenic injury in poly trauma patients was reported to be 44% and combined splenic and he- patic lesions in (18%) [1]. Splenic injuries represent ap- proximately 25% of all blunt injuries to the abdominal viscera. Penetrating injuries also frequently involve the spleen along with other abdominal o rgans [2]. The recent trend in management of splenic trauma is preservation whenever possible. This can be non-operative or opera- tive splenorrhaphy [3]. This follows the evolution in treatment of traumatic injuries of liver and spleen from aggressive to damage control surgery to non-operative [4]. Trends in management have changed over the years. Traditionally, laparotomy and splenectomy were the standard management. Presently, selective non-opera- tive management (SNOM) of splenic injury is the most common management strategy in haemodynamically stable patient [5,6]. Laparoscopic splenectomy was suc- cessfully carried out for the first time in colonoscopic grade IV splenic injury [7]. Patients who are haemody- namically stable can be safely treated with SNOM [8,9]. The splenic arterial embolization in haemodynamically stable patients has been attributed to the relatively high failure rate of such a treatment (10% - 31%), with a re- *Corresponding a uthor.  I. O. IBRAHIM ET AL. 526 sultant need for secondary splenectomy, and to the po- tential of missing other intra-abdominal injuries that re- quire laparotomy [9]. 2. Patients and Methods This is a prospective, observational and an alytic study. It is a hospital based, Multicenteric, conducted at the three main Teaching hospitals at Khartoum “Omdurman, Khartoum and Khartoum North”. The study was carried over a period extending from April 2012 to February 2013. It includes all patients, diagnosed as traumatic splenic injury by clinical assessment, investigations, or surgery. Excluded were patients with history of splenic disease, injury due to surgery or spontaneous rupture. Consecutive no n probability sampling was adop ted. Data were collected using, questionnaire. The variables in- clude personal data, presenting features, blood and radio- logical investigations, treatment, operative findings and post-operative complications. Patient’s informed consent was obtained, together with ethical clearance. Statistical analysis methods used were frequencies and 95% confi- dence intervals (CI) for categorical data, mean, standard deviation, frequencies and compared the data, using Stu- dent’s t-test and Chi-square tests when appropriate with significance taken at P value < 0.05. 3. Results The study included 47 patients, their mean age was 26.4 years (SD ± 14.5) and ranging from 2 to 65 years. Most of them 41 (87.2%) were in the first four decades of life. One third was in the age group 21 - 30 years Table 1. Males were predominant 41 (87.2%), with a male to female ratio of 6.8:1. The majority of our patients had blunt abdominal trauma 39 (83%), the rest 8 (17%) were resulted from penetrating injuries. Road traffic accident , fall off a height, falling object and other assault ac- counted for 51.1% 19.1%, 8.5% and 4.3% respectively, Table 2. Worth mentioning all penetrating cases were knives stab and no reported cases of gunshot, shotgun or impalement in this study. Only five patients (10.6%) Table 1. Age distribution in the study population (n = 47). Age (years) Frequency (%) 0 - 10 08 (17.0) 11 - 20 90 (19.1) 21 - 30 14 (29.8) 31 - 40 10 (21.3) 41 - 50 30 (6.4) 51 - 60 01 (2.1) >60 20 (4.3) Total 47 (100) presented to the surgical casualty within the first hour, more the half between 1 - 6 hours and 36.6% after six hours. Trauma does not respect any system, it involved the abdominal only in 23 (48.9%), whereas that associated with chest injury in 11 (23.4), head and neck 9 (19.1%) and extremities 4 (8.5%) respectively. With respect to the associated intra-abdominal injuries, in the vast majority of our patients, isolated splenic injury was found to be involved in 33 (70%) of the occasions and other organs were affected to lesser extend Table 3. Haemodynamic stability was seen in 27 (57.4%) on presentation, the rest were shocked. The initial haemoglobin assessment re- vealed <9 gram/dl in 53.2%, and >9 gram/dl in 46.8% of our patie nts. CT scan was performed to 24 (51.1%) and Focused Abdominal Sonography for Trauma (FAST) to 5 (10.6%) of the patients. Grade I and II were seen equally by the CT scan in 33.3% each, whereas Grade III and Grade IV were seen in 12.5% and 20.8% respectively and none of our patients was di agnosed as Grade V b y the scan. Blood transfusion was required in 42 (89.4%) and 16 (34%) patients received more than four pints of blood, 15 (31.9%) received 1 - 2 pints, 11 (23.4%) received 3 - 4 pints and only 5 pati e nt s ne eded no bloo d t r ansfusio n. Operative treatment was adopted in 66% (61.7% total splenectomy and 4.3% Splenorrhaphy), while ‘SNOM’ in 16 (34%) of the patients. In the latter group initially they were 19 patients however the conservative measures Table 2. Mode of trauma causing splenic injury. Mode of trauma Frequency Percent Road traffic accident 24 51.1% Fall off a height 09 19.1% Stab wound 08 17.0% Gunshot 00 0.00% Others 06 12.8% Total 47 100 Table 3. Associated intra-abdominal injuries. Organ injured Frequency Percent Spleen only 33 70.2% Small bowel & mesentery05 10.6% Stomach 04 8.5% Large bowel 02 04.3% Liver 01 02.1% Kidney 01 02.1% Others 01 02.1% Total 47 100 Open Access SS  I. O. IBRAHIM ET AL. 527 were successful in 84.2% of them and three patients were operated. These converted patients were all initially haemodynamically stable, and on laparotomy no associ- ated intra-abdominal injuries were found but the splenic trauma was grade IV in two patients and grade III in the third one. Fortunately three of the shocked patients were treated non-operatively after stabilization; two of them had associated chest injuries and the third with head and neck injury. The amount of haemoperotenium in the operated group, was found to be <50 0 ml in 4 (12 .9%), 500 - 1000 ml in 13 (41.9%) and >1000 ml in 14 (45.2%), Figure 1. Higher intra-operative grade of splenic injury was found to be significantly associated with; blunt abdomin- al trauma, haemodynamic instability on presentation, need for blood transfusion, presence of large amount of haemoperotenium and associated intra-abdominal inju- ries Table 4. Post-operatively 7 (14.9%) were ad mitted to the Inten- sive Care Unit “ICU”, 5 (10.6%) to the High Depend- ency Unit “HDU” and the rest to the general ward. Forty four patients (93.6%) were discharged home in good general condition Morbidity and Mortality The morbidity in our study occurred in four patients (8.5%), two cases of minor surgical site infection, one developed over-whelming post splenectomy sepsis Figure 1. Fluid (Blood) detected by FAST in splenic injury. (a) In Morison’s pouch. (b) In the pelvis (Rectovesicular space). Table 4. Factors predicting higher grade of splenic injuries. Factor P value Blunt trauma 0.002 Haemodynamic instability 0.023 Need for blood transfusion 0.036 Presence of haemoperotenium 0.000 Associated abdominal injuries 0.002 (OPSS) and one had mesenteric vascular occlusion. There are three deaths (6.4%) in this study. All received operative management, two after fail conservation. As- sociated extra-abdominal injuries were found in two of them (left haemothorax/massive intracranial bleeding). The length of hospital stay in our series varies between one week in (25%) to three weeks in (17%) and the rest 57% between one and three w e eks. 4. Discussion The mean age of 26.4 years (SD ± 14.5) in our study was found to be consistence with the reported age in another study done in Nigeria, mean of 24.2 ± 15.2 years [10]. However it was lower than 38 ± 16 (SD) years [11] and 32 years [6]. The male’s gender constitutes the great majority 78.2% in our study. This was found to be similar to the reported in the literature 63% [12,1 3] and 76% [6], how- ever our males where seven times the females number 6.8:1, which was higher compared to 3.9:1 [11], 2.2:1 [10], and 1.9:1 [14]. This can be explained by the fact males were breadwinners and the increase road traffic in the capital. 4.1. Mode of Trauma in Splenic Injury Blunt abdominal trauma was the commonest cause of splenic injury in our study (83%). This is comparable to the reported mode of trauma in other studies which range from 78% to 100% [5,10,12,13,15]. Motorcycle accidents, assaults, fall from height, and sports, were the varieties causing blunt splenic injuries [15]. Jason J. Hallman, et al., on their study of 338 splenic trauma as an adverse effect of torso-protecting side airbags, occupants involv- ed in left-side impacts without SAB, sustained injuries to their abdomen in 8.2% [16]. In our study, road traffic accidents were the reason in half the patients. This is similar to other studies, 42.9% [12], 57% [11], however, it is lower than 75.3% [10], 78% [13], 84% [6] and 91% [14] in other series. Falling off a height rank second in our study as a cause of blunt splenic injury which is com- parable to [5,10]. Our third cause was assaults and none of our patients inflicted sport injuries. All penetrating splenic injuries we received were cases of knives stab and no reported cases of gunshot. This contrasts the find- ing in Los Angeles, California were gunshot accounted for 70.4% of penetrating injuries to the spleen [17], this discrepancy might be attributed to variations in cultural context of the different communities, as knives were be- ing carried by some of Sudanese tribes as part of their traditional heritage and self-defense weapon. Haemodynamic instability was defined by a systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mm Hg refractory to re- suscitation maneuvers [11]. It was one of the presenting Open Access SS  I. O. IBRAHIM ET AL. 528 features of our patients and seen in 42.6%. This contrast the reported 6.6% in the literature [17] and possibly the paucity of efficient ambulance system with it is trained emergency medical personnel’s is a contributory factor. 4.2. Scanning The primary goal of splenic ultrasonography in the set- ting of blunt abdominal trauma is to detect the presence of blood in the left upper quadrant [2]. FAST is used in haemodynamic stable patients, takes 2 min, has no role in grading with a sensitivity of 90% [5] and it replace diag- nostic peritoneal lavage (DPL). It had been done to only five of our patients (10%), none availability of the ultra- sound in the emergency room or untrained surgical resi- dents may be responsible for this low percentage of per- formance. FAST detecting haemoperitoneum should lead to a CT scan for further evaluation of the nature and extent of injury [5]. CT scan is the modality used at most institu- tions. It provides the best evaluation of the sp leen and the surrounding tissues. It images all of the abdominal or- gans simultaneously to exclude secondary injury [2]. It was been performed to half of our patients and revealed grade III and IV in 33.3%, though these high grades of splenic injuries were diagnosed in 73% in Clay et al., study [18]. 4.3. Selective Non-Operative Management The initial choice of su rgical versus nonsu rgical manage- ment remains controversial [9]. Observational manage- ment involves admission to a unit with monitoring of vital signs, strict bed rest, frequent monitoring of red blood cell count, and serial abdominal examinations [5]. The American College of Surgeons’ National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB 4.0) analyzed 35,767 splenic injuries. There was a significant increase in percentage of SNOM [19]. This was in line with our trend where SNOM was adopted in 34% of our patients and similar to 39.5% in Bertrand, et al., in 2003 [11], but even higher than re- ported in the literature, 3.5% [17] and 6.8% [10]. 4.4. Operative Management Operative treatment was adopted in 66% of our patients. Other studies were in the range of 46% - 59.9% [12,14, 15,17]. Total splenectomy 61.7% was the commonest operation performed in our splenic injured patients. In the literature the rate range was 32% - 72% [10,12,14, 15,20]. Whereas Splenorrhaphy was practiced in 4.3% of our patients and this simulate others’ findings [20,21], but lower than 19.2% in a Nigerian study [10]. None of our patients underwent partial splenectomy neither splenic artery embolization. The latter modality of treat- ment was not practiced in our setting due to lack of ex- pertise personnel. 4.5. Outcome Uneventful discharge was seen in 93.6% of our patient compared to 86.3% in other study [10]. Three patients died, making a mortalit y of 6.4% in our study. Th is over- all mortality is comparable to 3.8% [13]. However, it was lower than 10.9 % [12] and 19% [15] in other studies. Our study has some limitations. The major limitations are, no unified guideline was used in the hospitals re- garding patients with splenic injuries, second FAST was not adopted universally in abdominal trauma patients, third the decision to operate was based on clinical judg- ment, fourth surgical registrar were not trained in the methods of splenic salvage fifth interventional radiolo- gist were not available for selective splenic artery em- bolization in minor grade of splenic injuries 5. Conclusion In conclusion, splenic injuries in o ur study usu ally follow blunt abdominal trauma, particularly after road traffic accidents. It is common during the first four decades of life with males being frequently affected. The outcome is excellent and the great success rate of adopting selective non-operative management is worthwhile in all hospitals. REFERENCES [1] B. Schnüriger, J. Kilz, D. Inderbitzin, M. Schafer, R. Kickuth, M. Luginbühl, et al., “The Accuracy of FAST in Relation to Grade of Solid Organ Injuries: A Retrospec- tive Analysis of 226 Trauma Patients with Liver or Splenic Lesion,” BMC Medical Imaging, Vol. 9, 2009, p. 3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2342-9-3 [2] S. R. Klepac, “Spleen Trauma Imaging,” 2011. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/373694-overview [3] H. L. Pachter and J. Grau, “The Current Status of Splenic Preservation,” Advances in Surgery, Vol. 4, No. 34, 2003, pp. 137-174. [4] S. Di Saverio, E. E. Moore, G. Tugnoli, N. Naidoo, L. Ansaloni, S. Bonilauri, et al., “Non Operative Manage- ment of Liver and Spleen Traumatic Injuries: A Giant with Clay Feet,” World Journal of Emergency Surgery, Vol. 7, No. 3, 2012, pp. 1-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1749-7922-7-3 [5] C. H. van der Vliesm, O. M. van Delden, B. J. Punt, K. J. Ponsenm, J. A. Reekers and J. C. Goslings, “Literature Review of the Role of Ultrasound, Computed Tomogra- phy and Transcatheter Arterial Embolization for the Treatment of Traumatic Splenic Injuries,” CardioVascu- lar and Interventional Radiology, Vol. 33, 2010, pp. 1079-1087. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00270-010-9943-6 [6] J. M. Haan, G. V. Bochicchio, N. Kramer and T. M. Scalea, “Nonoperative Management of Blunt Splenic In- jury: A 5-Year Experience,” The Journal of Trauma In- Open Access SS  I. O. IBRAHIM ET AL. Open Access SS 529 jury, Infection, and Critical Care, Vol. 58, 2005, pp 492- 498. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.TA.0000154575.49388.74 [7] S. Abunnaja, L. Panait, J. A. Palesty and S. Macaron, “Laparoscopic Splenectomy for Traumatic Splenic Injury after Screening Colonoscopy,” Case Reports in Gastro- enterology, Vol. 6, 2012, pp. 624-628. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000343428 [8] S. A. Rehim, H. Dagash, P. P. Godbole, A. A. Raghavan and G. V. Murthi, “Subtle Radiological Features of Splenic Avulsion Following Abdominal Trauma,” Case Reports in Medicine, Vol. 2010, 2010, pp. 1-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2010/762493 [9] D. S. P. Popovic and M. Jeromel, “Percutaneous Tran- scatheter Arterial Embolization in Haemodynamically Stable Patients with Blunt Splenic Injury,” Radiology and Oncology, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2010, pp. 30-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/v10019-010-0011-2 [10] E. A. Agbakwuru, A. A. Akinkuolie, O. A. Sowande, O. A. Adisa, O. I. Alatise, U. U. Onakpoya, O. Uhumwango and A. R. K. Adesukanmi, “Splenic Injuries in a Semi Urban Hospital in Nigeria,” East and Central African Journal of Surgery, Vol. 13, No. 1, 2008, pp. 95-100. [11] B. Bessoud, A. Denys, J.-M. Calmes, D. Madoff, S. Qanadli and P. Schnyder, “Nonoperative Management of Traumatic Splenic Injuries: Is There a Role for Proximal Splenic Artery Embolization?” AJR, Vol. 186, No. 3, 2006, pp. 779-785. http://dx.doi.org/10.2214/AJR.04.1800 [12] S. Sinha, S. V. V. Raja and M. H. Lewis, “Recent Changes in the Management of Blunt Splenic Injury: Ef- fect on Splenic Trauma Patients and Hospital Implica- tions,” Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of Eng- land, Vol. 90, No. 2, 2008, pp. 109-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1308/003588408X242033 [13] J. A. Weinberg, L. J. Magnotti, M. A. Croce and N. M. Edwards, “The Utility of Serial Computed Tomography Imaging of Blunt Splenic Injury: Still Worth a Second Look?” The Journal of Trauma Injury, Infection, and Cri- tical Care, Vol. 62, No. 5, 2007, pp. 1143-1148. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e318047b7c2 [14] A. A. Akinkuolie, O. O. Lawal, O. A. Arowolo, E. A. Agbakwuru and A. R. K. Adesunkanmi, “Determinants of Splenectomy in Splenic Injuries Following Blunt Abdo- minal Trauma,” SAJS, Vol. 48, No. 1, 2010, pp. 15-19. [15] T. C. König, N. R. M. Tai and M. S. Walsh, “Blunt Splenic Trauma,” Annals of The Royal College of Sur- geons of England, Vol. 90, No. 7, 2008, pp. 626-627. http://dx.doi.org/10.1308/003588408X321602 [16] J. J. Hallman, K. J. Brasel, N. Yoganandan and F. A. Pintar, “Splenic Trauma as an Adverse Effect of Torso- Protecting Side Airbags: Biomechanical and Case Evi- dence,” Annals of Advances in Automotive Medicine, Vol. 53, 2009, pp. 13-24. [17] D. Demetriades, P. Hadjizacharia, C. Constantinou, C. Brown, K. Inaba, P. Rhee and A. Salim, “Selective Nono- perative Management of Penetrating Abdominal Solid Organ Injuries,” Annals of Surgery, Vol. 244, No. 4, 2006, pp. 620-628. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000237743.22633.01 [18] C. C. Burlew, L. Z. Kornblith, E. E. Moore, J. L. Johnson and W. L. Biffl, “Blunt Trauma Induced Splenic Blushes Are Not Created Equal,” World Journal of Emergency Surgery, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2012, p. 8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1749-7922-7-8 [19] M. Hurtuk, R. L. Reed, T. J. Esposito, K. A. Davis and F. A. Luchette, “Trauma Surgeons Practice What They Preach: The NTDB Story on Solid Organ Injury Man- agement,” Journal of Trauma, Vol. 61, No. 2, 2006, pp. 243-254. [20] A. Mikocka-Walus, H. C. Beevor, B. Gabbe, R. L. Gruen, J. Winnett and P. Cameron, “Management of Spleen Inju- ries: The Current Profile,” ANZ Journal of Surgery, Vol. 80, No. 3, 2010, pp. 157-161. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05209.x [21] S. R. Todd, M. Arthur, C. Newgard, J. R. Hedges and R. J. Mullins, “Hospital Factors Associated with Splenectomy for Splenic Injury: A National Perspective,” Journal of Trauma, Vol. 57, 2004, pp. 1065-1071. Abbreviations DPL: Diagnostic peritoneal lavage, FAST: Focused Abdominal Sonography for Trauma, HDU: High Dependency Unit, OPSS: Over-whelming post splenectomy sepsis, SNOM: Selective non-operative management.

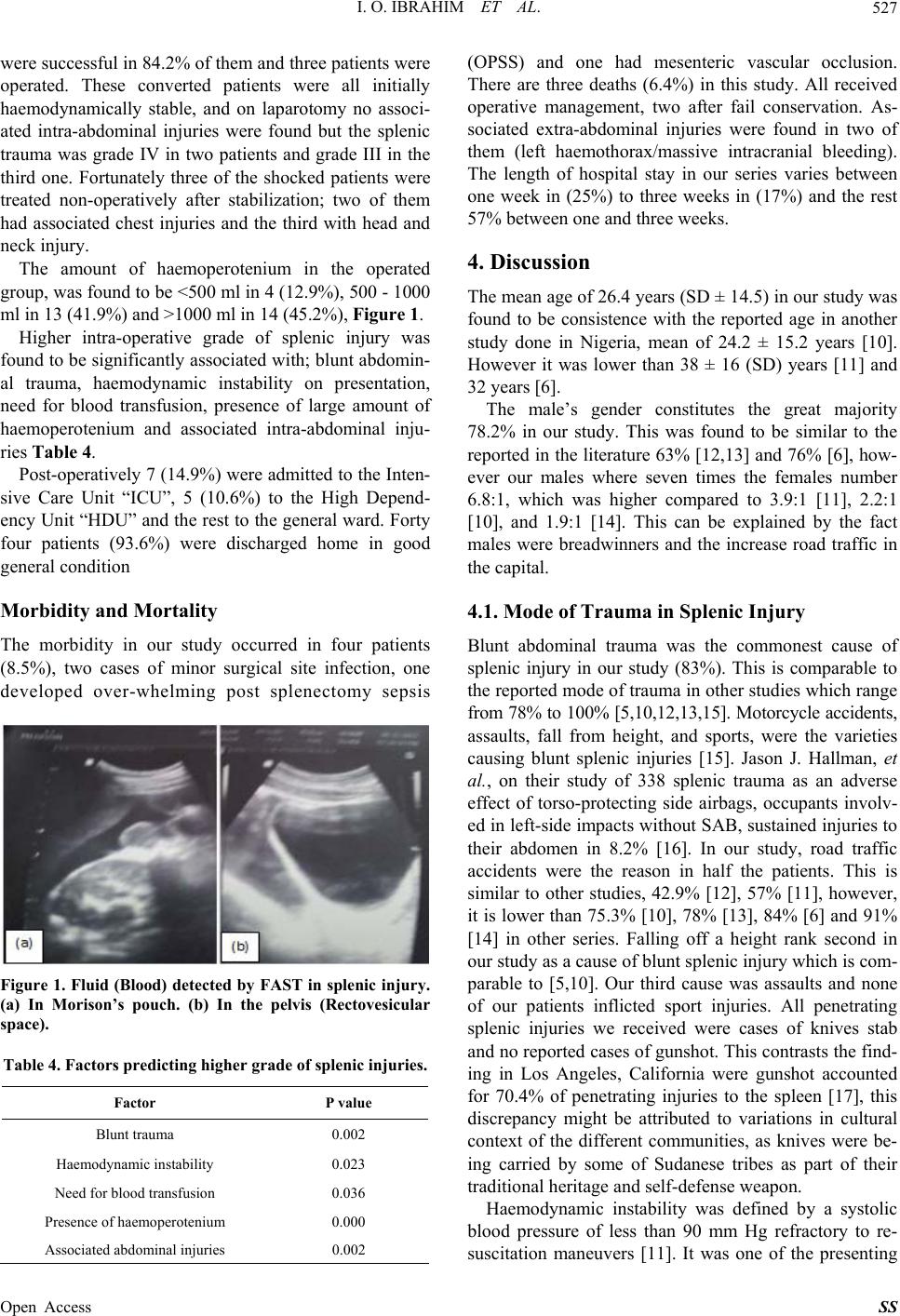

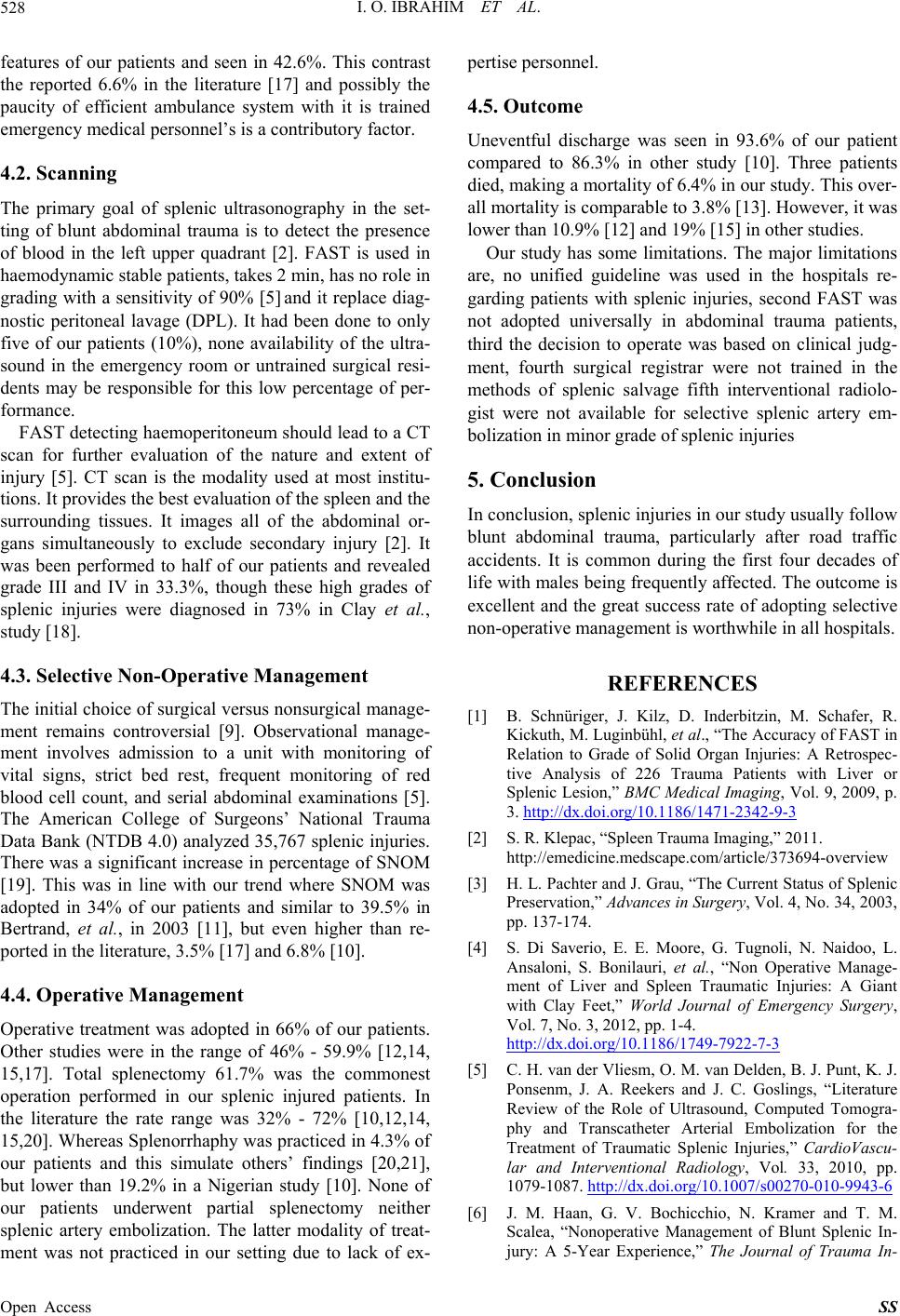

|