Open Journal of Social Sciences 2013. Vol.1, No.6, 43-49 Published Online November 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/jss) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jss.2013.16009 Open Access 43 Parental Authority Styles of Parents with Attention Deficit Disorders (ADD) Hadas Doron, Adi Sharbani Tel-Hai Academic College, Tel Hai, Israel Email: hadasdoron@012.net.il Received November 2013 The aim of the present study is to examine the differences between parents (mothers and fathers) with at- tention deficit disorders (ADD), and parents without ADD, regarding their characterizing parenting style (permissive, authoritarian and authoritative) according to Baumrind (1971, 1991). Many theories have aimed to describe and conceptualize the concept of parental authority style. The present research uses Baumrind’s (1971, 1991) theory, which offers three characteristic styles of parental authority, addresses the ways in which parents settle the needs of their children, by means of nurturing and limit setting, each according to his typical style: permissive, authoritarian and authoritative. The point of departure for this study is, that the parent’s gender in combination with the parent being diagnosed as with ADD, will pre- dict his parental authority style. Different researches in the field of Attention Deficit disorders (ADD) point to gender differences in different characteristics along developmental stages from childhood to adulthood (Chen, Seipp, & Johnson, 2008). Thus, we postulated that fathers with ADD will be character- ized as with different parenting styles than mothers with ADD, and in comparison to a control group. Based on different studies, we assumed that fathers with ADD will be characterized by a less responsible behavior, yet they will be more direct and active; while mothers with ADD will be typified as more inva- sive, demanding and negative (Berger & Landau, 2009; Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2008). In addition, we hypothesized that fathers with ADD will be found as more permissive compared to the control group, while mothers with ADD would be more authoritative compared to the control group. The sample in- cluded 62 men, 30 with ADD and 32 control subjects without ADD, and 61 women, 30 with ADD and 31 without ADD. In order to examine the hypotheses subjects were instructed to reflect upon their parenting style in present and/or in the past, and to report it while completing the questionnaire. Parental authorita- tive style was examined by means of the Parental Authority Questionnaire (PAQ) developed by Buri (1991), measuring the parenting styles as conceptualized by Baumrind. The findings of the research re- veal no significant differences between fathers and mothers without ADD, in neither of the parenting styles, also no significant difference was found between with ADD and mothers without ADD in each of the parenting styles. Keywords: Attention Deficit Disorders (ADD); Permissive Parenting Style; Authoritarian Parenting Style; Mothers Authority; Fathers Author i t y Attention Deficit Disorder and Gender Differences amo ng Adults According to Rucklidge, Brown, Crawford & Kaplan (2007) today approximately 2% of the adult population is affected by the disorder. Biederman et al. (2004), Hun lee, Oakland, Jack- son & Glutting (2008) maintain that in adulthood the incidence of the disorder is comparatively more balanced between gend- ers than in childhood (2:1 for males in relative to females). Rasmussen & Levander (2009) and Chtonis-Tuscano et al. )2008( claim that today there are more evidence that the dis- order commenced in childhood and pertains in adulthood. However less studies address ADD in adulthood and fewer deal with gender differences among adults with ADD (Rucklidge et al., 2007). Rasmussen & Levander (2009) mentioned that most of the studies in this field were based on male subjects. A study by Biederman et al. (2004) have found a co-morbid- ity of at least one additional disorder among 34% of the women with ADD and among 50% of the men. Among women a lower prevalence was found of conduct disorders (a combined disord- er of affect and behavior) or of antisocial disorder than among men. In Rasmussen & Levander’s study (2009), a significant difference was found between genders in emotional disorders (more women) and in dyslexia (more men). Among children no significant difference was found in these fields. However among men, as in children, studies documented a more externa- lized behavior than among women. Also a significant differ- ence was found with regard to abuse and delinquency, which was found more prevalent among men. Another study found that women with ADD have less assets, lower self perception, and more problems than men, all of which may lead to higher dependency towards their male counterparts (Quinn, 2005; Rasmussen & Levander, 2009). Furthermore, it was found that students that report them- selves as having ADD are less achievers than students that do not report having ADD. The former report concerns regarding their academic achievements, higher levels of stress, social difficulties and rate themselves as less emotionally stable. Ad- ditionally, they were more prone to alcohol abuse as well as to smoking and using marihuana. Although success during school is marked, and in light of the fact that they succeed in being  H. DORON, A. SHARBANI Open Access accepted to superior academic institutions, research have found that hardships and efforts go on throughout life (Blasé, 2009). In the field of parenthood solely scarce research was con- ducted, nevertheless Quinn (2005) found that women that were not diagnosed with ADD, compared to diagnosed women, were more capable of consistency as parents, and were less “getting along” at work and in the household. In contrast, Rucklidge et al. (2007) mention that they did not found any differences be- tween women with ADD, and men with ADD. Biederman et al. (2004) found that adult men and women with ADD have de- mographic, psychosocial and cognitive patterns that are com- patible with findings that were recorded with young boys and girls with the disorder. Parental Authority At first, researchers have tried to conceptualize parental au- thority styles based on specific parenting characters, yet those efforts failed to supply a clear and inclusive image, within the concoction of complex parenting traits. With the development of research in this field, three determinants were given major attention, which provide a clearer and more effective picture: the emotional climate between a parent and his child, parenting methods, i.e. parents’ behaviors and customs, and the par enting beliefs system towards which the child’s socialization is di- rected on behalf of his parents (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). Therefore this model offers to examine the parenting style throughout the array of attitudes directed by t he parent towards the child, embedding all of the feelings, gestures and behaviors, through which, in practice, the parent performs his role in face of his child (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). Baumrind’s (1971) parental authority model defines parental authority as a set of approaches underlying parents’ behaviors towards their child. This behavior, as a part of the socialization, includes all the goal-directed acts of parenting practice, as well as those that are not goal-directed such as body gestures, voice intonation or the spontaneous change of emotional expressive- ness, meaning—the emotional climate. Baumrind’s (1971) study also gives rise to the idea that the child’s socialization—allowing him to adapt and conform to essential environmental demands while preserving a certain sense of personal entirety—is the key to parents’ functioning. Hence the concept of “parental authority” has developed, a con- cept formerly being perceived as strictness, as using physical and consistent punishment etc. In contrast, Baumrind called for a conceptual distinction in using the term “parental authority”, which in her study meant the parent’s demand of his child’s behavioral adaptation as a part of his integration in the familial and social settings. In light of this definition, we can acknowledge the impor- tance in imparting and delineating emotional patterns, methods and values, derived from parenting styles and parenting values and beliefs regarding the essence of their role and the nature of their child (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). Baumrind was distinguished from other researchers of her time, in that she defined “parental authority” as a broader pa- renting function, and instead of organizing it in a linear manner, from low authority to high authority, she differentiated between three styles of parental authority, each has distinctive characte- ristics: Permissive, authoritarian and authoritative (Baumrind, 1966, 1967). Herrin after we present in detail each of the parenting styles according to Baumrind: Parental Authority Styles Three Parental Authority Styles Model According to Baumrind A factor analysis of parents’ behaviors yielded two evident dimensions, the first ‘demanding’ and the second “responsibili- ty”. Within the model offered by Baumrind three quintessential styles of parental authority were found, describing how parents, by setting and fostering limits, settle their children’s needs. The distinction of each style depends upon the social content, the developmental stage and evaluation methods (Baumrind, 1991; Buri, 1991). Permissive Parenting Style Parents with this “non-directive” style are characterized by over permission in face of their children’s demands towards them, compared to the number of times in which parents set demands to their children. Also these parents ar e usually readily to make concessions, avoid conflicts and external limit setting, and allow their children to explore and examine their environ- ment and their boundaries of self regulation by themselves, while independently making decisions according to their will. In fact, these parents, relatively, lack control over their children and tend to use the least possible means of punishment. This parenting style integrates high parental support, low control and little demands for mature behavior. These parents usually gained a similar way of upbringing from their parents (Bau- mrind, 1971, 1991; Buri, 1991). Authoritarian Parenting Style Authoritarian parents are characterized by demand and di- recting, nevertheless they are characterized by emotional dis- tance, i.e.—lack of warmth. They demand obedience and in accordance they do not encourage independence and free will from the part of their children. They are guided by the role they have undertaken, with the expectation that their instructions be fulfilled without any explanations or verbal negotiation in the form of “give and take”, with a preference towards punishment means to control the children. However, they provide an orga- nized environment, clear instructions and meticulous supervi- sion on their children deeds. This style of parenting integrates both coercive control efforts and low support. Authoritative Parenti ng Style Authoritative parents tend to be located between the edges of the two other styles mentioned above. They are characterized by demand and responsibility. They believe in and acknowl- edge their rights and duties as parents, and accordingly they supervise and set clear and consistent demands, according to which they expect their children to act. These parents are asser- tive, yet not invasive or binding, due to their recognition of their child’s uniqueness and will. Their approach is typified by support, warmth, flexibility, abilities to understand and com- municate with their children, implementing reason and a “give and take” verbal negotiation instead of punishment and expec- tations for obedience. Their expectations however are that their children be assertive and socially responsible, as well as orga- nized and cooperative. Thus one can observe integration be- tween the demands for maturity from the children on one hand, while affording high parental support and a warm climate from the other hand. These parents are aware to the possibility that they are apt to mistakes in their lives and that they are not a  H. DORON, A. SHARBANI Open Access single and definite authority in their children’s lives. Later in her study, Baumrind (1991) expended her model to include a fourth parenting style, one she defined as “rejecting- neglecting”. This “disengaged” parenting style is characterized by low levels of responsiveness and demand from the part of the parents. They are not understood, not responsible, not sup- portive and even actively reject their children, or alternatively neglect them or any accountability for them. The present research will not refer to this last parenting style due to its extremism. In the past attention deficit was investigated solely among children, yet nowadays, however the scarce research in this field, it is well knows that attention deficit disorder persists to adulthood. In a research conducted in 2006 it was found that adults with ADD have, in addition to difficulties in school, also occupational, social and parental difficulties, compared to adults without ADD (Rasmussen & Levander, 2009). Chen et al. (2009) claim that many of the existing researches addressed the relationships between the mother and the ADD child, yet the few studies that addressed the relationship be- tween the father and the ADD child found significant differ- ences in their attitude and parental behavior compared to the mothers. Familial studies regarding child ren with ADD fou nd that 15% - 20% of mothers and 20% - 30% of fathers by themselves have ADD. Estimates are that 60% of children to diagnosed parents are likely to be diagnosed themselves as with ADD. This inter- generational transmission was mainly attributed to develop- mental neurological, social and intellectual vulnerability. How- ever, organic environment, familial influences and unfavorable patterns of interaction between parents and their children were also found as influential (Amiel-Laviad, Atzaba-Poria, Auer- bach, Berger, & Landau, 2009; Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2008; Daley, Psychogiou, Sonuga-Barke, & Thompson, 2008). Recently more and more research was devoted to investigat- ing the variance in parental behavior between parents with ADD, compared to parents without ADD. Sychogiou, Daley, Thompson & Sonuga (2007) studied the relation between par- ents with ADD and their children and found significant deficits in the parenthood of the diagnosed group. Murry & Johnson (2006) fortify this argument through some studies, which point to a negative relation between parental qualifications and ADD symptoms. Studies that rely primarily on self-report scales, suggest that parents with ADD have higher probability of decreased quality of parenthood, they are more likely to display more negative and chaotic parenthood, with higher levels of familial conflict and lower levels of coherence. This parenthood style is characterized by impulsive decision making that is expressed by difficulty to restrain reactions and by high emotional involvement, and may find expression in rigidity and physical or verbal punishments, that many times are unsuitable to the situation, even not in relation to former conduct in similar situations. Additionally, this parenthood style is characterized by inconsistency, recurring action and lessened ability of self observation. In light of the above, one may come to see how ADD nega- tively influences the quality of parenthood, parent-child rela- tionships, effective parental supervision, social relations and the ability to implement structured and organized techniques of parenting. Moreover, it was found that parental and familial roles are violated when one of the parents have ADD. It seems that the presence of one disorganized, non-attentive and hyper- active partner may interfere with the total organization, and may still weaken the parenting behavior of the partner without ADD (Murry & Johnson, 2006). Some studies on fathers with ADD found that they showed less responsible behaviors in parent-child interaction compared to mothers however fathers were found to be more direct and overly active (Amiel-Laviad, Atzaba-Poria, Auerbach, Berger, & Landau, 2009; Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2008). Other studies conducted on mothers with ADD revealed that they displayed more invasiveness, demanding/sermonizing and negativity such as: ordering the child without allowing him to reply; less approving and encouraging and express less positive emotion, compared to mothers without ADD. In addition these mothers were characterized by poorer supervision of their child’s behavior, due to lower levels of involvement; less con- sistency in disciplinary matters and also showed lower levels of effectiveness in their problem solving skills. Method Population 123 participants (see Table 1) comprised the sample. Partic- ipants were required to be parents to at least one child, no age limitation. The subjects’ average age was 39.97 years ±8.35. Subjects were samples by convenience sampling method, i.e. the researchers were assisted by their acquaintances in order to collect subjects according with the research’s criterions. Tools Research data was collected through the following question- naires: Table 1. Description and distribution of sample’s characteristics. % N Variable 50.4 62 Male Gender 49.6 61 Female 26.8 33 Diagnosed ADD 51.2 63 Not diagnose d 22.0 27 Not diagnose d, but displays symptoms 13.8 17 Secondary Education 17.9 22 tertiary 48.8 60 BA 19.5 24 MA+ 23.6 29 1 No. of children 22.7 28 2 36.6 45 3 17.1 21 4+ 56.1 69 0 No. of diag nos ed children 43.9 54 1+ 46.9 53 Therapeutic Professi on 53.1 60 Non-therapeutic  H. DORON, A. SHARBANI Open Access • Demographic questionnaire—this questionnaire was as- sembled for the purpose of the present research and in- cluded the following details: age, gender, diagnosed as with ADD or not, education, no. of children, no. of ADD diag- nosed children, familial status and occupation. For the pur- pose of statistical analysis, answers to the following va- riables were united into wider categories: • “Diagnosed as with ADD” and “not diagnosed but displays symptoms”were unite d into a “yes” ADD category. • Parental authority style questionnaire—in this research, we used a questionnaire relying upon Buri’s (1991) PAQ (parental Authority Questionnaire) developed in order to measure the parenting styles according to Bau mrin d’s (1991) conceptualization (permissive, authoritarian, authoritative). Buri’s questionnaire consists of 30 items, 10 dedicated to each parenting style (i.e. item 14 for permissive style: “I usually do what my children want when making familial de- cision”; item 4 for authoritative style: “I usually communi- cate to my child the reason behind setting family policy”; and item 12 for authoritarian style: “I think that smart par- ents should teach their children in an early stage who is the boss in the family”). The questionnaire was translated to Hebrew and validated by Sholet (1997), and adapted as a self-report measure to parents, hereinafter—self evaluation of parenting style—by Zafrir (2001). In Buri’s (1991) study internal consistency ranged be- tween 0.74 to 0.87. In Sholet’s study, (1997) internal consis- tency for the three style was: 0.79 for authoritative style, 0.85 for authoritarian style and 0.65 for permissive style. In Zafrir’s (2001) stu dy , the internal consistency was: 0.78 for authoritative style, 0.72 for authoritarian style and 0.83 for permissive sty le. The parental authority scale was based on Likert scale, rang- ing from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Reliabilities for the items are presented in Table 2. Procedure The questionnaires were administered in some manners: 1) distributed by email to parents, with and without ADD; 2) dis- tributed through the support center for learning disabilities in Tel Hai College; 3) published in an internet forum for adults with ADD; 4) distributed through a group facilitator that in- structs a support group for parents with ADD that takes place in the regional council of northern Galilee in Israel. Mostly reservations rose regarding the phrasing of two items, i.e. item 8 (“I instruct and guide my child’s decisions and ac- tions by persuasion and discipline”) and item 13 (“I seldom set expectations and guidelines to my child regarding his beha- vior”). These items were removed from t he statistical analy s is. Findings Our research’s goal was to examine the differences between parents (mothers and fathers) with ADD and parents without ADD, regarding their parental authority style. In addition, we examined whether gender differences exist in parental authority style. Our first hypothesis was that fathers with ADD would be more permissive compared to fathers without ADD. In order to test the hypothesis means and Sd’s were calculated for each parental authority style (permissive, authoritative, authoritarian) among both groups (ADD/no ADD). The hypothesis was tested through t-test for independent samples (see Table 3). Table 3 shows that no difference was found between fathers with ADD and fathers without ADD in each of the parental styles (p > 0.05), therefore, hypothesis 1 was refuted. The second hypothesis was that mothers with ADD would be more authoritarian in their parental style, compared to mothers without ADD. In order to test this hypothesis means and Sd’s were calculated for each parental authority style (permissive, authoritative, authoritarian) among both groups (ADD/no ADD mothers). The hypothesis was tested through t-test for indepen- dent samples (see Table 4). Table 4 shows that no difference was found between moth- ers with ADD and mothers without ADD in each of the parental styles (p > 0.05), therefore, hypothesis 2 was refuted. Additional Findings Table 5 presents the relation between parents’ academic de- gree and their being with our without ADD. Table 5 shows that there is a significant difference between Table 2. Results of Reliability tests (of internal consistency) to the parental authority questionnaire, means, Sd’s and ranges for each factor. Parental style items removed items Scale range Reliability (α) Mean Sd. actual range Permissive 1, 6, 10, 13, 14, 17, 19, 21, 24, 28 13* 1 - 5 0.707 2.40 0.52 1.33 - 3.78 Authoritative 3, 27, 30, 4, 5, 11, 15, 20, 22, 8 8* 1 - 5 0.731 4.09 0.45 2.00 - 5.00 Authoritarian 2, 3, 7, 9, 12, 16, 18, 25, 26, 29 1 - 5 0.735 2.52 0.54 1.20 - 3.70 Note: *These items evoked many complaint s regardi ng their phrasing. Table 3. Means and Sd’s of parental authority styles among father with and without ADD, and t-tests for independent samples. Parental style Fathers with ADD (n = 30) Fathers without AD D (n = 30) M Sd M Sd t p Permissive 2.39 0.54 2.47 0.52 −0.621 0.537 Authoritarian 4.09 0.39 4.07 0.57 0.154 0.878 Authoritative 2.51 0.54 2.53 0.55 −0.200 0.842  H. DORON, A. SHARBANI Open Access Table 4. Means and Sd’s of parental authority styles among mothers with and without ADD, and t-tests for independent samples. Parental style mothers with ADD (n = 30) mothers without ADD (n = 31) M Sd M Sd t p Permissive 2.35 0.55 2.41 0.50 0.476− 0.636 Authoritarian 4.08 0.42 4.13 0.42 0.439− 0.662 Authoritative 2.50 0.57 2.53 0.54 0.204− 0.839 Table 5. The relation between the parents’ academic degree and ADD. secondary tertiary BA MA+ χ2 p N % N % N % N % With ADD 6 35.3 11 50 38 63.3 5 20.8 13.839** 0.003 Without ADD 11 64.7 11 50 22 36.7 19 79.2 Note: **p < 0.01. the existence of ADD and the subject’s academic degree. It shows that among 24 subjects with MA or higher education solely 20.8% have ADD, compared to 79.2% that do not have ADD. Next we aimed at examining whether there were differences in the response pattern towards each parental style between parents with and without ADD. In order to achieve this, we conducted the following steps: A factor analysis was conducted for each parental style in order to locate the most significant questions it contains. It was found that the most significant items for the permissive style were items 1 and 28. For the authoritative style items were 5 and 11, and for the authoritarian style items 3 and 16 were found most significant. Later all ratings to these items were re-coded on a trans- formed scale from 5 levels to 3 levels as follows: 1 - 2 in the former scale were coded as 1 (negative ratings), 3 was coded as 3 (neutral rating) and 4 - 5 in the former scale were coded as 5 (positive rating). A χ2 analysis was conducted in order to examine the relation between the respondent’s ADD and his ratings to the items that were identified in the factor analysis (see above paragraph). Table 6 shows that the most significant items for each pa- rental style. It can be seen that parents with ADD were more negative towards the permissive style, compared to parents without ADD. Discussion The present research examined the relation between the par- ents’ ADD and their parental style. Our hypotheses were that fathers with ADD would be more permissive in their parental style, compared to fathers without ADD; while mothers with ADD would show a more authoritarian style compared to mo- thers without ADD. Both hypotheses were refuted (see Tables 3 and 4). The Relation between Parental Style and the Parent’s ADD In our research we have found a trend that can be observed in Table 6, which points to the fact that parents with ADD tend to hold more negative positions towards permissiveness, com- pared to parents without ADD. This finding is somewhat sup- ported by Tables 3 and 4 that show a tendency among parents with ADD towards a less pe rmissive stand, compared to parents without ADD. This stands in contradiction with the trend pre- sently characterizing western society, in which there is a col- lapse of parental and instructional authority in the course of the last decades, in relation to the traditional parental authority (The admission of the permissive parenthood style stems mainly from the fact that many attributes of the “old authority”, such as: physical punishments, distancing, unconditional obedience etc., are no longer perceived as legitimate and as conventions as they were before. Nowadays, a widespread notion is that authorita- rian parents compelling limits upon their children, hinders their growth and development (Omer, 2008). Our finding can therefore be accounted for by the DSM-IV (2000), in which people with Attention Deficit Disorder are described as people easily distracted by external stimulus, as having hardships in emotional regulation, internal restlessness and apt to forgetting and disorganization. Following the will to relieve the internal sense of disorganization among adults with ADD in general, and among parents in particular, and due to the effort to “survive” daily life, parents with ADD adapt a coping style that allows them to preserve a sense of control, order, stability and routine in their lives. Thus this rationale penetrates also their parental style and their relations with their children. Research Limitations The current research bears some shortcomings that should be addressed, as follows: 1) A formal diagnosis for ADD was not required from the participants in order to participate in the ADD group. There- fore, this makes the generalization of the research’s findings on parents that are diagnosed with ADD, harder. 2) The subjects’ age range was relatively wide (standard deviation of 8.35 years). This may bring about potentially inter- vening age-related variables, ones that were not taken into ac- count in the research. 3) We used a convenient sample. This sampling method al- lows for the possibility that the sample does not reliably rep- resent the relevant population.  H. DORON, A. SHARBANI Open Access Table 6. Frequency of ratings to identified items in each parental style in both groups (ADD/no ADD). ADD (n = 59) no ADD (n = 54) Positive Negative Positive Negative N % N % N % N % χ2 p item 1 34 73.9 12 26.1 29 54.7 24 45.3 3.921* 0.048 items 11 3 5.4 53 94.6 2 3.6 53 96.4 0.191 0.662 item 3 44 84.6 8 15.4 36 70.6 15 29.4 2.921 0.087 Note: *p < 0.05. 4) We encountered some difficulties in administering ques- tionnaires to fathers with ADD or with symptoms. Recommendations for Further Research In light of the present findings, we attribute great importance to carrying out a research aimed at inquiring the relation be- tween choosing a therapeutic/helping profession and parental authority style among the general population, as well as among parents with ADD. Another innovative research direction should address the population of parents with a therapeutic profession, and ex- amine whether their parental style is a valid predictor for their professional practice, the type of treatment they grant to their patients, and their therapeutic approach. In addition, we rec- ommend examining whether there are unique parental styles characterizing parents with ADD or alternatively, as was done in the current study, Baumrind’s typology suffices in characte- rizing ADD parents’ patterns. Since some participants in our study attested on themselves as having symptoms of attention deficit disorder, but were not medically diagnosed for ADD, future research should include only diagnosed subjects and by this to resolve some of the cur- rent research’s shortcomings and fortify the comprehension regarding parents with ADD. REFERENCES American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., pp. 85-92). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. Amiel-Laviad, R., Atzaba-Poria, N., Auerbach, J. G., Berger, A., & Landau, R. (2009). Parenting of 7-month play, with restrictions on interaction. Infant Behavior & Development, 32, 173-182. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.12.007U Balint, S., Czobor, P., Ko mlosi, S., Meszaros, A., Simon, V., & Bitter, I. (2008). Attention deficit h yperactivit y disorder (ADH D): Gender and age related differences in neurocognirion. Psychological Medicine, 39, 1337-1345. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291708004236U Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Develop- mental Psychology Monograph, 4, 1-103. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0030372U Baumrind, D. (1991). The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substan ce us e. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 11, 56-95. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0272431691111004U Baurmeister, J., Shrout, P., Chavez, L., Rubio-stipec, M., Ramirez, R., Padilla, L., Anderson, A., Garcia, P., & Canino, G. (2007). ADHD and gender: Are risks and sequqla of ADHD the same for boys and girls. Journal of Child P s ychology and Psy chiatry, 48, 831-839. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01750.xU Biederman, J., Far aone, S., Monuteau x, M., Bober, M., & Cadogen, E. (2004). Gender effects on attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults, revisited. Society of Biological Psychiatry, 55, 692-700. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.003U Biederman, J., M ick, E., Fa raone, S. V. , Braaten , E., Do yle, A., Spencer, T., Wilnes, T. E., Frazie, E., & Johnson, M. A. (2002). Influence of gender on attention d eficit hyperactivity disord er in children referred to psychiatric clinic. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 36-42. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.36U Blase, S. L. (2009). Self-reported ADHD and adjustment in college: Cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Journal of Attention Dis- orders, 13, 297. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1087054709334446U Bremmer, L. M. (1994). Helping relationships: Processes and mean- ings (pp. 39-60). Haifa: “Ach” Publishing. Buri, J. R. (1991). Parental authority questionnaire. Journal of Perso- nality Assessment, 57, 110-119. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_13U Carlton, M., Jewell, J. D., Krohn, E. J., Meinz, E., & Scott, V. G. (2008). The differential of mothers’ and fathers’ discipline on pre- school children’s home and classroom behavior. North America Journal of Psychology, 10, 173-188. Chen, M., Seipp, C ., & Johnson, C. (2008). Mothers’ and fathers’ attri- butions and beliefs in families of girls and boys with attention- defi- cit/hyperactivity disorder. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 39, 85-99. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10578-007-0073-6U Chronis-Tuscano, A., Clark e, T. N., Diaz, Y., Ragg i, V. L., Pian, J. , & Rooney, M. E. (2008). Associations between maternal attention-de- ficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and parenting. Journal of Ab- normal Child Psy chology, 36, 1237-1250. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9246-4U Cory, M. S ., & Co ry, G. (1998). Becomin g a helper (3rd ed., pp. 2-27). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Col e. Daley, D. M., Psychogiou, L., Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S., & Thompson, M. J. (2008). Do maternal attention-deficit/hyperactivity di sorder symp- toms exacerbate or ameliorate th e neg ativ e ef fect o f ch illed atten tio n- deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms on parenting? Developmen- tal and Psychopathology, 20, pp. 121-137. Darling, N., & Stei n b e rg , L. (1 9 9 3 ). Pa ren ting style a s co n text: An inte- grative model (pp. 487-496). Washington, DC: American Psychiatri c Association. Gerby, I. (19 96). The double price: Women status and military service in Israel. Tel Aviv University: Ramot Publishing. Hatev, Y., & Sha’har, A. (2002). ADHD cultu ral aspects. Nefesh (Sou l), 10, 71-77. Hopkins, H., Klein, H. A., & O’bryant, K. (1996). Recalled parental authority style and self-perception in college men and women. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 157, 5-17. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00221325.1996.9914842U Hun Lee, D., Oak land , T., J acks on , G., & Gluttin g, J. (200 8). Estimated prevalence of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms among college freshmen: Gender, race, and rater effects. Journal of Learn- ing Disabilities, 41, 371- 384. Korat, A. (2008). AD(H)D: Attention deficit d isorder a mong adults. J e- rusalem: Keter Publishers LTD. Lavigne, J., Lebailly, S., Hopkins, J., Gouze, K., & Binns, H. (2009). The prevalence of ADHD, ODD, depression, and anxiety in a com- munity sample of 4-year-olds. Journal of Clinical Child & Adoles- cent Psychology, 38, 315-328.  H. DORON, A. SHARBANI Open Access http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374410902851382 Lerman, M. (2003). Psycho logical evaluation and diagnosis in ADHD. In: E. Manor, & S. Tiano, (Eds.). Living with ADHD (pp. 193-208). Tel Aviv: Diunon Publishing. Loe, I., Bal estrino, M., Phelps, R., Kurs-Lasky, M., Chaves-Gnecco, D., Paradise, J., & Feldman, H. (2008). Early histories of school aged children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Child Devel- opment, 79, 1853-1868. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01230.xU Murry, C., & Johnson, C. (2006). Parenting in mothers with and with- out attention deficit/hyperactivit y diso rder. Journal of Abnormal Psy- chology, 115, 52-61. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.52U Omer, H. (200 8). New authority—In th e family, school and commu nity. Beit Shemen: Modan Publishing. Psychogiou, L., Daley, D., Thompson, M., & Sonuga-Barke, E. (2007 ). Testing the interactive eff ect of parent and ch ild ADHD on p arenting in mothers and fathers: Further test of the similarity-fit hypothesis. British Journal of Developmental Psychological, 25, 419-433. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1348/026151006X170281U Quinn, P. (2005). Treating adolescent girls and woman with ADHD: Gender specific issues. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61, 579-587. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20121U Rasmussen, K., & Levander, S. (2009). Untreated ADHD in adults. Journal of Attention Disorders, 12, 353-360. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1087054708314621U Rucklidge, J., Brown, D., Crawford, S., & Kaplan, B. (2007). Attribu- tional styles and psychosocial functioning of adults with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 10, 288-298. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1087054706289942U Throell, L. B., & Rydell, A.-M. (2008). Behaviour problems and social competence deficits associated with symptoms of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder: Effects of age and gender. Child: Care, Heal- th and Development, 34, 584-595. Uhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00869.xU

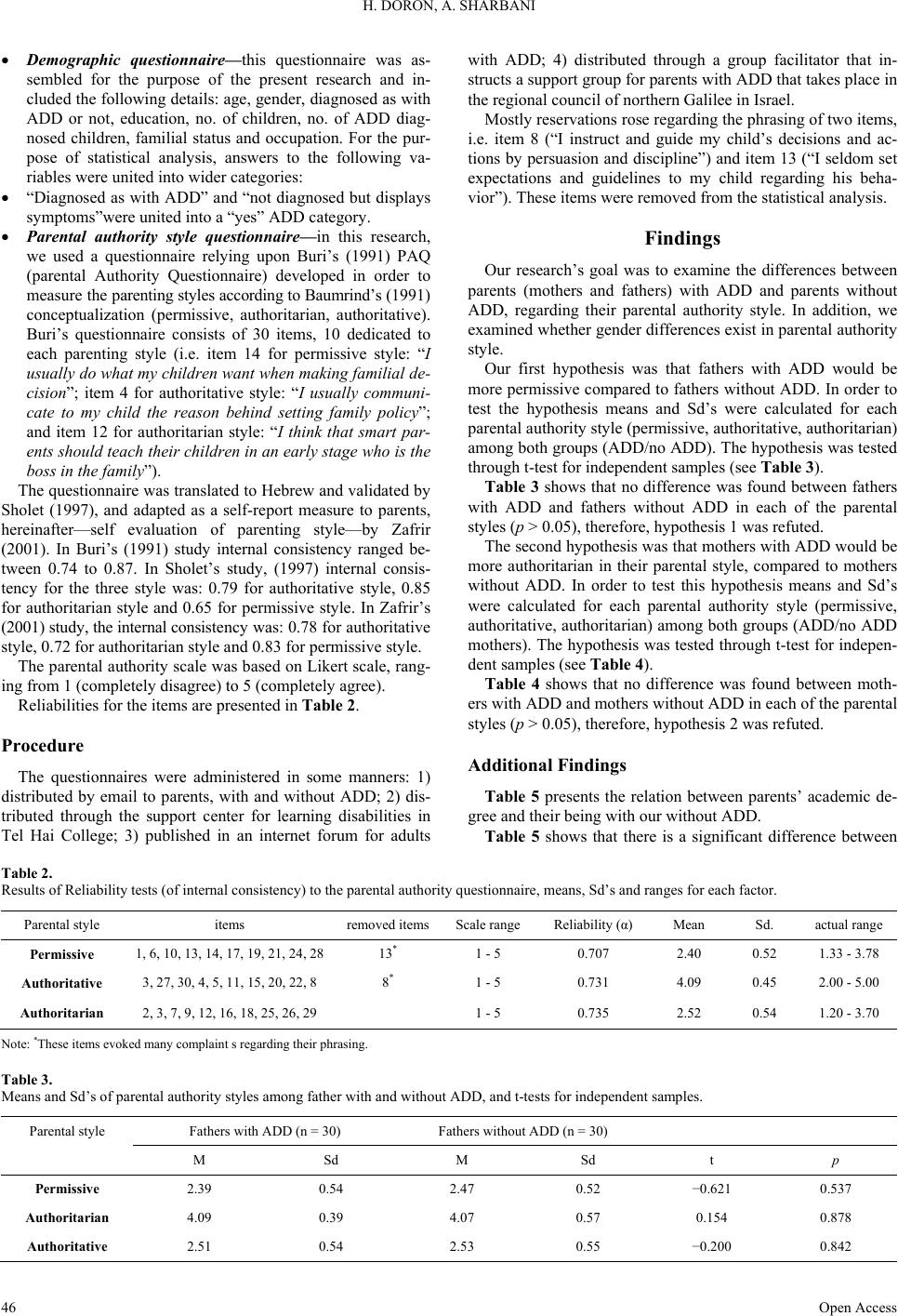

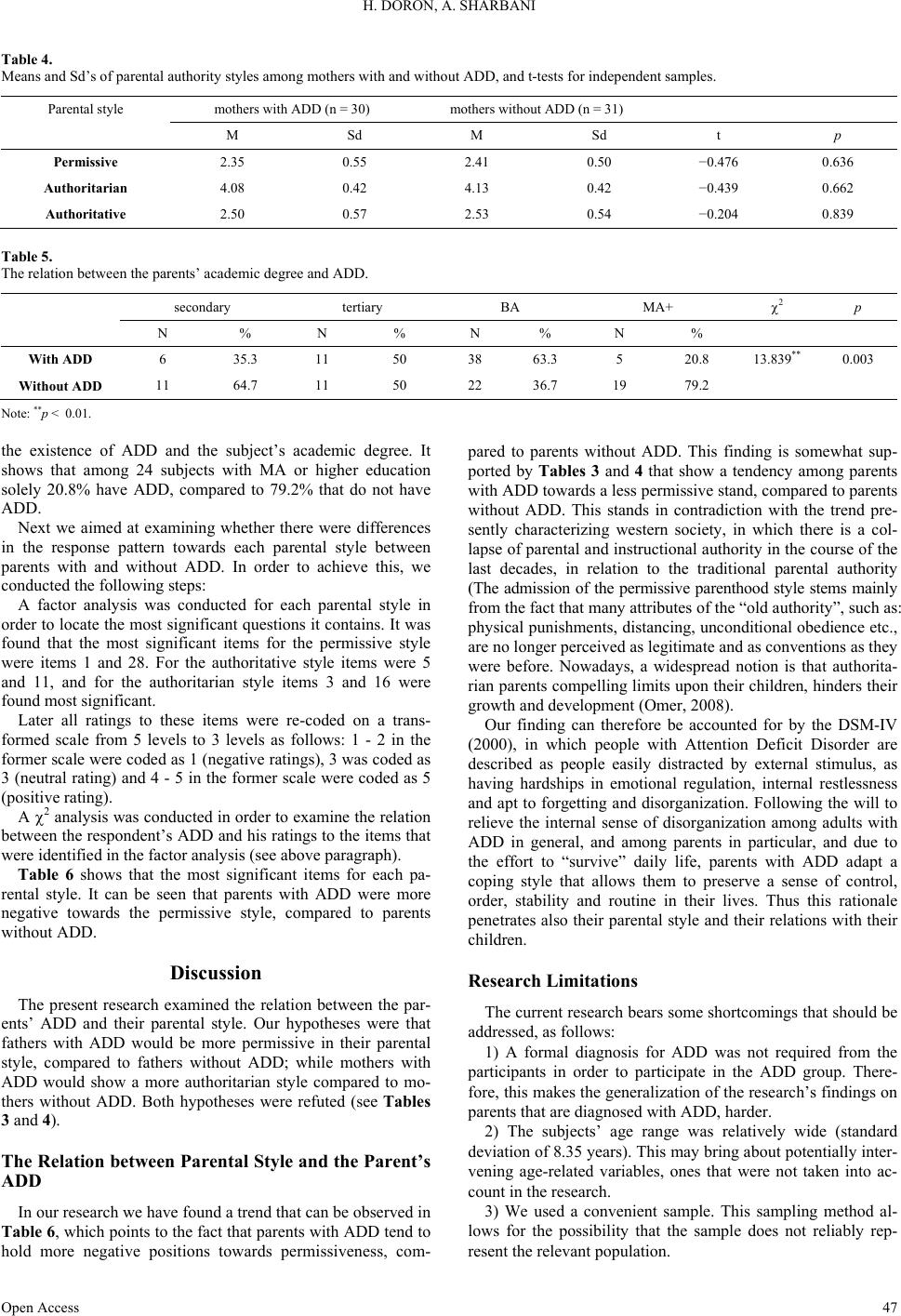

|