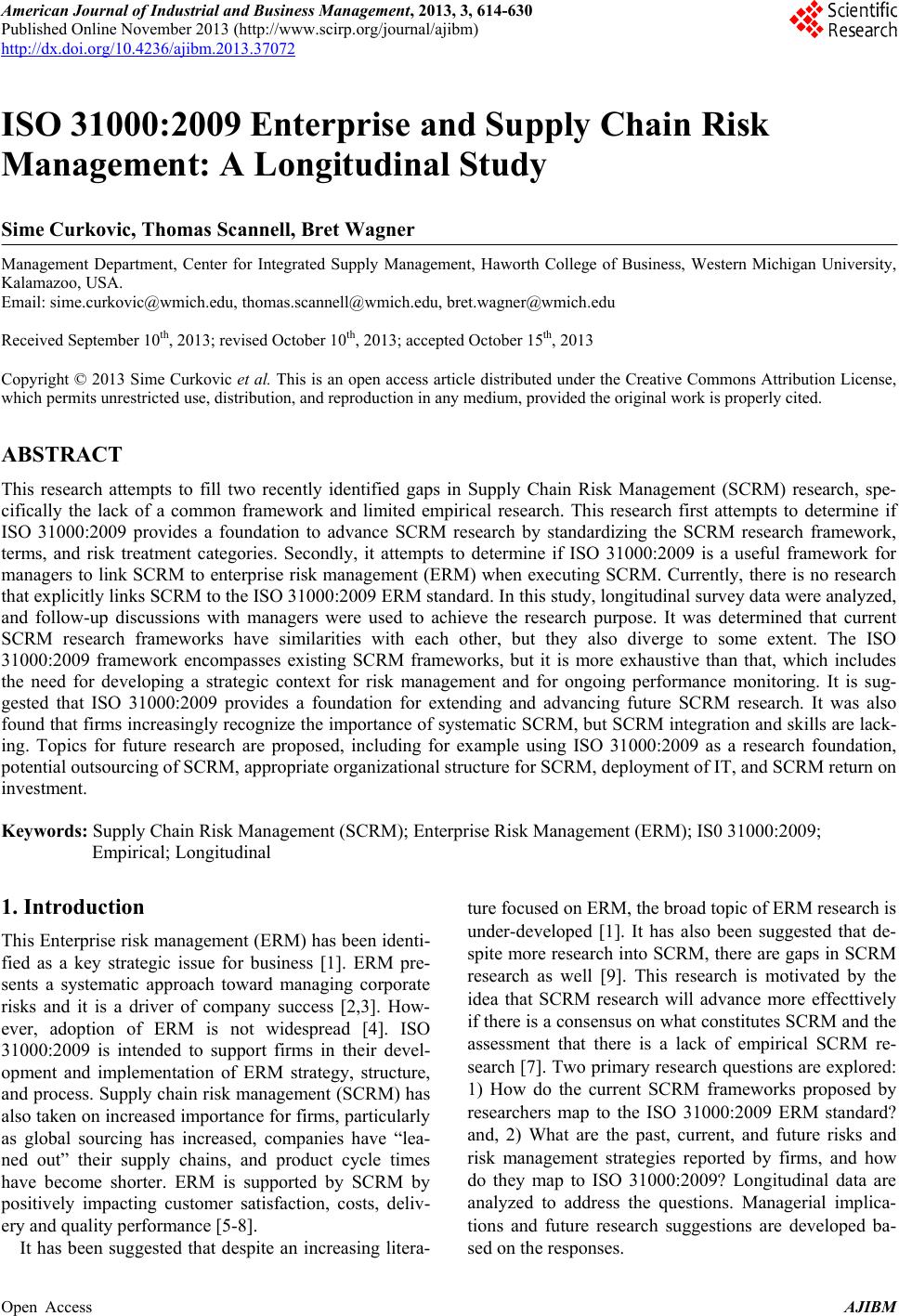

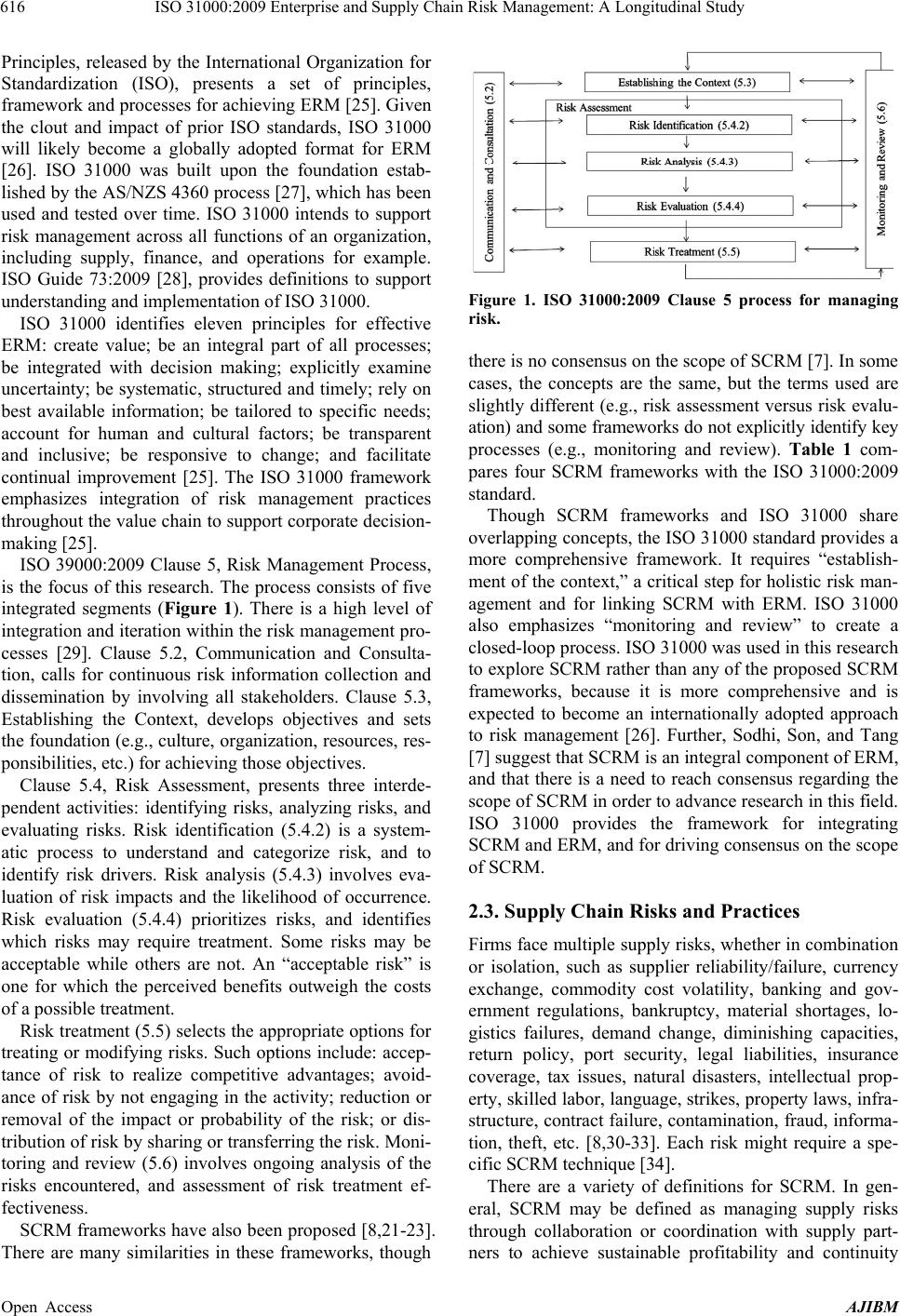

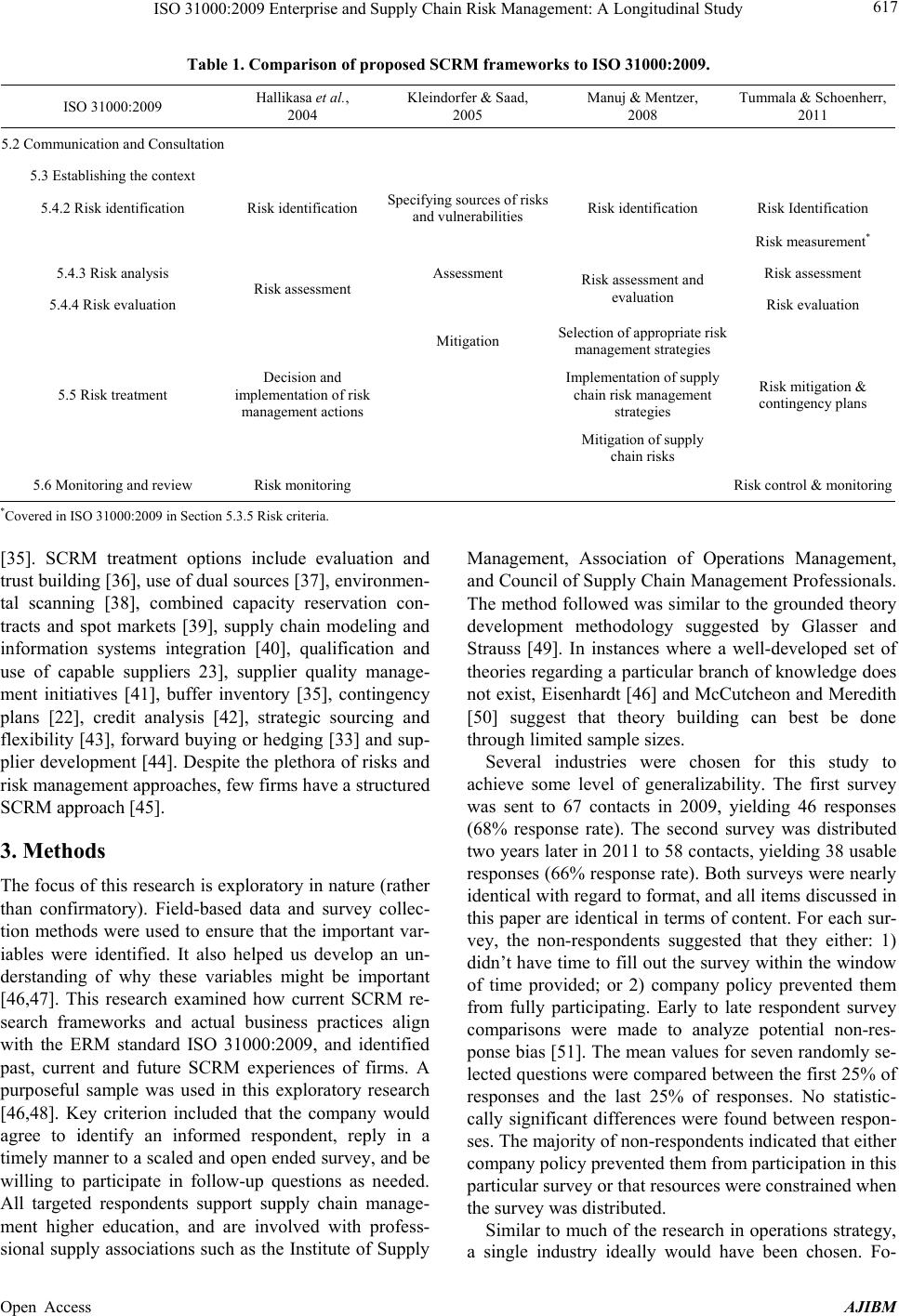

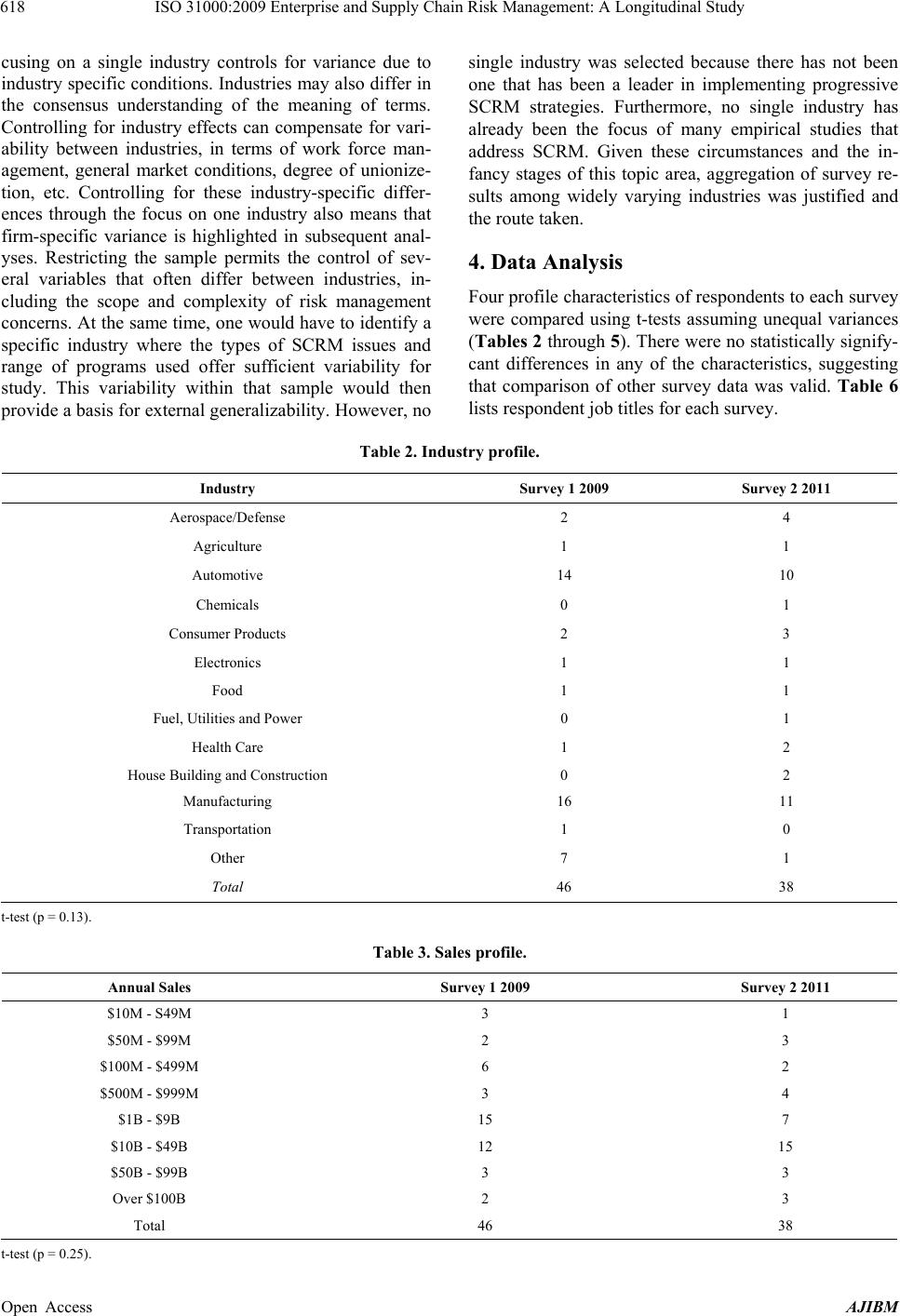

American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 2013, 3, 614-630 Published Online November 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajibm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2013.37072 Open Access AJIBM ISO 31000:2009 Enterprise and Supply Chain Risk Management: A Longitudinal Study Sime Curkovic, Thomas Scannell, Bret Wagner Management Department, Center for Integrated Supply Management, Haworth College of Business, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, USA. Email: sime.curkovic@wmich.edu, thomas.scannell@wmich.edu, bret.wagner@wmich.edu Received September 10th, 2013; revised October 10th, 2013; accepted October 15th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Sime Curkovic et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT This research attempts to fill two recently identified gaps in Supply Chain Risk Management (SCRM) research, spe- cifically the lack of a common framework and limited empirical research. This research first attempts to determine if ISO 31000:2009 provides a foundation to advance SCRM research by standardizing the SCRM research framework, terms, and risk treatment categories. Secondly, it attempts to determine if ISO 31000:2009 is a useful framework for managers to link SCRM to enterprise risk management (ERM) when executing SCRM. Currently, there is no research that explicitly link s SCRM to the ISO 310 00:2009 ERM stand ard. In this stu d y, longitu dinal surv ey data were an alyzed, and follow-up discussions with managers were used to achieve the research purpose. It was determined that current SCRM research frameworks have similarities with each other, but they also diverge to some extent. The ISO 31000:2009 framework encompasses existing SCRM frameworks, but it is more exhaustive than that, which includes the need for developing a strategic context for risk management and for ongoing performance monitoring. It is sug- gested that ISO 31000:2009 provides a foundation for extending and advancing future SCRM research. It was also found that firms increasingly recognize the importance of syste matic SCRM, but SCRM integration an d skills are lack- ing. Topics for future research are proposed, including for example using ISO 31000:2009 as a research foundation, potential outsourcing of SCRM, appropriate organizational structure for SCRM, deployment of IT, and SCRM return on investment. Keywords: Supply Chain Risk Management (SCRM); Enterprise Risk Management (ERM); IS0 31000:2009; Empirical; Longitudinal 1. Introduction This Enterprise risk management (ERM) has been identi- fied as a key strategic issue for business [1]. ERM pre- sents a systematic approach toward managing corporate risks and it is a driver of company success [2,3]. How- ever, adoption of ERM is not widespread [4]. ISO 31000:2009 is intended to support firms in their devel- opment and implementation of ERM strategy, structure, and process. Supply chain risk management (SCRM) has also taken on increased importance for firms, particularly as global sourcing has increased, companies have “lea- ned out” their supply chains, and product cycle times have become shorter. ERM is supported by SCRM by positively impacting customer satisfaction, costs, deliv- ery and quality performance [5-8]. It has been suggested that despite an increasing litera- ture focused on ERM, the broad topic of ERM research is under-developed [1]. It has also been suggested that de- spite more research into SCRM, there are gaps in SCRM research as well [9]. This research is motivated by the idea that SCRM research will advance more effecttively if there is a consensu s on what constitutes SCRM and the assessment that there is a lack of empirical SCRM re- search [7]. Two primary research questions are explored: 1) How do the current SCRM frameworks proposed by researchers map to the ISO 31000:2009 ERM standard? and, 2) What are the past, current, and future risks and risk management strategies reported by firms, and how do they map to ISO 31000:2009? Longitudinal data are analyzed to address the questions. Managerial implica- tions and future research suggestions are developed ba- sed on the responses.  ISO 31000:2009 Enterprise and Supply Chain Risk Management: A Longitudinal Study 615 The findings indicate that despite firms that are re- porting an increased recognition of SCRM importance, SCRM approaches tend to be ad-hoc rather than inte- grated. It was also found that actual SCRM practices and proposed SCRM frameworks all map well to ISO 310 00. Thus, for practitioners, ISO 31000 provides a foundation for linking SCRM to ERM, and for developing SCRM strategy and processes. For researchers, ISO 31000 pro- vides a reasonable framework that could accelerate the understan di n g of SCR M . In the next section, the literature review discusses gaps in SCRM research, explores the ISO 31000 ERM stan- dard, compares existing SCRM frameworks with ISO 31000, then briefly identifies supply risks and SCRM practices. The methodology is then presented and the sur- vey data results are then su mmarized. Finally, the results are interpreted and discussed, using qualitative feedback from practitioners to support the discussion. 2. Literature Review 2.1. CRM Research Gaps The advancement of any field or strategic initiative (e.g., Total Quality Management, Mass Customization , Just-In- Time Manufacturing, Supply Chain Risk Management) requires empirically based research whose thrust is the development and validation of frameworks, concepts and measurement instruments. For example, the TQM disci- pline required that an operational definition and stan- dardized framework be developed and validated in order for theory building to advance (see for example [10-15]). By doing so, the TQM discipline moved from the impor- tant contributions of anecdotes and case studies (the cur- rent state of SCRM research) to testable models and spe- cific research hypotheses, linking the theoretical concept of TQM to empirical indicants. Operational definitions and standardized frameworks have contributed to TQM theory-building by identifying the constructs associated with TQM, developing scales for measuring these con- structs, and empirically validating the scales. The SCRM research is in its infancy stages and requires the same type of research. Global competitive landscapes and increasingly com- plex supply chain processes and partnerships, coupled with increased requirements to comply with regulations, laws and industry guidelines has heightened awareness that firms may benefit from a systematic approach to risk management. SCRM has garnered significant academic, consultant, and practitioner interest over the last decade as a way to not only mitigate risk, but to take advantage of risk opportunities [2,16]. SCRM is a pr ocess for iden- tifying, analyzing and proactively planning responses to a portfolio of risks [17,18]. Though effective SCRM can provide significant bene- fits for a firm [2,3], a relatively small percentage of firms have a detailed understanding of this integrated process, and adoption of SCRM is rather limited [18]. Ad hoc approaches to risk management by various “silos” in an organization leads to duplication of resources, uncoordi- nated planning, and less efficien t and effective risk man- agement processes [2]. Varying frameworks have been proposed to support and standardize implementation of systematic SCRM. Sample frameworks include the Joint Australia/New Zealand AS/NZ 4360-2004, the Turnbull Guidance, and the ISO 31000 standards for risk man- agement. SCRM and related frameworks are not without de- tractors. There is a lack of empirical research into the effectiveness of SCRM in general [2] and the specific frameworks in particular. Other detractors note that im- plementing SCRM requires a substantial commitment of resources (time, personnel, money) that aren’t likely to be available during lean times, and a cultural shift of the entire organization [19] without an appropriate return on such efforts [20]. However, with appropriate planning and execution, SCRM frameworks may be implemented by any organization, from large to small firms [18,19]. Other SCRM frameworks have also been proposed [8, 21-23]. There are many similarities in these frameworks, though there is no consensus on the scope of SCRM [7]. In some cases, the concepts are the same, but the terms used are slightly different (e.g., risk assessment versus risk evaluation) and some frameworks do not explicitly identify key processes (e.g., monitoring and review). Sodhi, Son and Tang [7] identified multiple SCRM research gaps and recommended ways to close the gaps. One gap they identified is a lack of consensus regarding the definition and scope of SCRM. They suggested that there is a great need to reach a consensus on such issues in order to better communicate with company executives and practitioners, and to more quickly advance SCRM research. They also suggest that SCRM is a subset or extension of ERM [7]. Given their suggestions, the ISO 31000 ERM framework, developed by and for practitio- ners, was identified as a potential consensus framework for SCRM that could fill the research gap. Another gap they identified was a lack of empirical SCRM research, particularly in regard to understanding current practice. This empirical research focuses on current practice and is one important first step toward filling the empirical re- search gap. 2.2. ERM, ISO 31000:2009 and SCRM Frameworks Enterprise risk management (ERM) is a holistic approach to identify and manage corporate-wide risks to achieve long-term success [3]. Though ERM is an increasingly important topic for practitioners and researchers [2], it is not widely adopted [24]. ISO 31000 Risk Management Open Access AJIBM  ISO 31000:2009 Enterprise and Supply Chain Risk Management: A Longitudinal Study 616 Principles, released by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), presents a set of principles, framework and processes for achieving ERM [25]. Given the clout and impact of prior ISO standards, ISO 31000 will likely become a globally adopted format for ERM [26]. ISO 31000 was built upon the foundation estab- lished by the AS/NZS 4360 process [27], which has been used and tested over time. ISO 31000 intends to support risk management across all functions of an organization, including supply, finance, and operations for example. ISO Guide 73:2009 [28], provides definitions to support understan ding and implem entat i on of ISO 31000. ISO 31000 identifies eleven principles for effective ERM: create value; be an integral part of all processes; be integrated with decision making; explicitly examine uncertainty; be systematic, structured and timely ; rely on best available information; be tailored to specific needs; account for human and cultural factors; be transparent and inclusive; be responsive to change; and facilitate continual improvement [25]. The ISO 31000 framework emphasizes integration of risk management practices throughout th e value chain to support co rporate decision - making [25]. ISO 39000:2009 Clause 5, Risk Management Process, is the focus of this research. The process consists of five integrated segments (Figure 1). There is a high level of integration and iteratio n within the risk manag ement pro- cesses [29]. Clause 5.2, Communication and Consulta- tion, calls for continuous risk information collection and dissemination by involving all stakeholders. Clause 5.3, Establishing the Context, develops objectives and sets the foundation (e.g., culture, organization, resources, res- ponsibilities, etc.) for achieving those objectives. Clause 5.4, Risk Assessment, presents three interde- pendent activities: identifying risks, analyzing risks, and evaluating risks. Risk identification (5.4.2) is a system- atic process to understand and categorize risk, and to identify risk drivers. Risk analysis (5.4.3) involves eva- luation of risk impacts and the likelihood of occurrence. Risk evaluation (5.4.4) prioritizes risks, and identifies which risks may require treatment. Some risks may be acceptable while others are not. An “acceptable risk” is one for which the perceived benefits outweigh the costs of a possible treatment. Risk treatment (5.5) selects the appropriate options for treating or modifying risks. Such options include: accep- tance of risk to realize competitive advantages; avoid- ance of risk by not engaging in the activity; reduction or removal of the impact or probability of the risk; or dis- tribution of risk by sharing or transferring the risk. Moni- toring and review (5.6) involves ongoing analysis of the risks encountered, and assessment of risk treatment ef- fectiveness. SCRM frameworks have also been proposed [8,21-23]. There are many similarities in these frameworks, though Figure 1. ISO 31000:2009 Clause 5 process for managing risk. there is no consensus on the scope of SCRM [7]. In some cases, the concepts are the same, but the terms used are slightly different (e.g., risk assessment versus risk evalu- ation) and some frameworks do not explicitly identify key processes (e.g., monitoring and review). Table 1 com- pares four SCRM frameworks with the ISO 31000:2009 standard. Though SCRM frameworks and ISO 31000 share overlapping concepts, the ISO 31000 standar d provides a more comprehensive framework. It requires “establish- ment of the context,” a critical step for holistic risk man- agement and for linking SCRM with ERM. ISO 31000 also emphasizes “monitoring and review” to create a closed-loop p rocess. IS O 31000 w as u sed in this resear ch to explore SCRM rather than any of the proposed SCRM frameworks, because it is more comprehensive and is expected to become an internationally adopted approach to risk management [26]. Further, Sodhi, Son, and Tang [7] suggest that SCRM is an integral component of ERM, and that there is a need to reach consensus regarding the scope of SCRM in order to advance research in this field. ISO 31000 provides the framework for integrating SCRM and ERM, and for driving cons ensus on the scope of SCRM. 2.3. Supply Chain Risks and Practices Firms face multiple supply risks, whether in combination or isolation, such as supplier reliability/failure, currency exchange, commodity cost volatility, banking and gov- ernment regulations, bankruptcy, material shortages, lo- gistics failures, demand change, diminishing capacities, return policy, port security, legal liabilities, insurance coverage, tax issues, natural disasters, intellectual prop- erty, skilled labor, language, strikes, property laws, infra- structure, contract failure, contamination, fraud, informa- tion, theft, etc. [8,30-33]. Each risk might require a spe- cific SCRM technique [34]. There are a variety of definitions for SCRM. In gen- eral, SCRM may be defined as managing supply risks through collaboration or coordination with supply part- ners to achieve sustainable profitability and continuity Open Access AJIBM  ISO 31000:2009 Enterprise and Supply Chain Risk Management: A Longitudinal Study Open Access AJIBM 617 Table 1. Comparison of proposed SCRM frameworks to ISO 31000:2009. ISO 31000:2009 Hallikasa et al., 2004 Kleindorfer & Saad, 2005 Manuj & Mentzer, 2008 Tummala & Schoenherr, 2011 5.2 Communication and Consultation 5.3 Establishing the context 5.4.2 Risk identification Risk identification Specifying sources of risks and vulnerabilities Risk identification Risk Identification Risk measurement* 5.4.3 Risk analysis Assessment Risk assessment 5.4.4 Risk evaluation Risk assessment Risk assessment and evaluation Risk evaluation Mitigation Selection of appropriate risk management str ategies Implementation of supply chain risk management strategies 5.5 Risk treatment Decision and implementation of risk management actions Mitigation of supply chain risks Risk mitigation & contingency plans 5.6 Monitoring and review Risk monitoring Risk control & monitoring *Covered in ISO 31000:2009 in Section 5.3.5 Risk criteria. [35]. SCRM treatment options include evaluation and trust building [36], use of dual sources [37], environmen- tal scanning [38], combined capacity reservation con- tracts and spot markets [39], supply chain modeling and information systems integration [40], qualification and use of capable suppliers 23], supplier quality manage- ment initiatives [41], buffer inventory [35], contingency plans [22], credit analysis [42], strategic sourcing and flexibility [43], forward buying or hedging [33] and sup - plier development [44]. Despite the plethora of risks and risk management approaches, few firms have a structured SCRM approach [45]. 3. Methods The focus of this research is exploratory in nature (rather than confirmatory). Field-based data and survey collec- tion methods were used to ensure that the important var- iables were identified. It also helped us develop an un- derstanding of why these variables might be important [46,47]. This research examined how current SCRM re- search frameworks and actual business practices align with the ERM standard ISO 31000:2009, and identified past, current and future SCRM experiences of firms. A purposeful sample was used in this exploratory research [46,48]. Key criterion included that the company would agree to identify an informed respondent, reply in a timely manner to a scaled and open ended survey, and be willing to participate in follow-up questions as needed. All targeted respondents support supply chain manage- ment higher education, and are involved with profess- sional supply associatio ns such as the Institute of Supply Management, Association of Operations Management, and Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals. The method followed was similar to the grounded theory development methodology suggested by Glasser and Strauss [49]. In instances where a well-developed set of theories regarding a particular branch of knowledge does not exist, Eisenhardt [46] and McCutcheon and Meredith [50] suggest that theory building can best be done through limited sample sizes. Several industries were chosen for this study to achieve some level of generalizability. The first survey was sent to 67 contacts in 2009, yielding 46 responses (68% response rate). The second survey was distributed two years later in 2011 to 58 contacts, yielding 38 usable responses (66% response ra te). Both surveys were nearly identical with regard to format, and all items discussed in this paper are identical in terms of content. For each sur- vey, the non-respondents suggested that they either: 1) didn’t have time to fill ou t the survey within the window of time provided; or 2) company policy prevented them from fully participating. Early to late respondent survey comparisons were made to analyze potential non-res- ponse bias [51]. The mean values for seven randomly se- lected questions were compared between the first 25% of responses and the last 25% of responses. No statistic- cally significant differences were found between respon- ses. The majority of non-r espo nd ents ind icated that eith er company policy prevented them from participation in this particular survey or that resources were constrained when the survey was distributed. Similar to much of the research in op erations strategy, a single industry ideally would have been chosen. Fo-  ISO 31000:2009 Enterprise and Supply Chain Risk Management: A Longitudinal Study 618 cusing on a single industry controls for variance due to industry specific conditions. Industries may also differ in the consensus understanding of the meaning of terms. Controlling for industry effects can compensate for vari- ability between industries, in terms of work force man- agement, general market conditions, degree of unionize- tion, etc. Controlling for these industry-specific differ- ences through the focus on one industry also means that firm-specific variance is highlighted in subsequent anal- yses. Restricting the sample permits the control of sev- eral variables that often differ between industries, in- cluding the scope and complexity of risk management concerns. At the same time, one would have to identify a specific industry where the types of SCRM issues and range of programs used offer sufficient variability for study. This variability within that sample would then provide a basis for extern al generalizability. However, no single industry was selected because there has not been one that has been a leader in implementing progressive SCRM strategies. Furthermore, no single industry has already been the focus of many empirical studies that address SCRM. Given these circumstances and the in- fancy stages of this topic area, aggregation of survey re- sults among widely varying industries was justified and the route taken. 4. Data Analysis Four profile characteristics of respondents to each survey were compared using t-tests assuming unequal variances (Tables 2 through 5). There were no statistically signify- cant differences in any of the characteristics, suggesting that comparison of other survey data was valid. Table 6 lists respondent job titles for each survey. Table 2. Industry profile. Industry Survey 1 2009 Survey 2 2011 Aerospace/Defense 2 4 Agriculture 1 1 Automotive 14 10 Chemicals 0 1 Consumer Products 2 3 Electronics 1 1 Food 1 1 Fuel, Utilities and Power 0 1 Health Care 1 2 House Building and Construction 0 2 Manufacturing 16 11 Transportation 1 0 Other 7 1 Total 46 38 t-test (p = 0.13). Table 3. Sales profile. Annual Sales Survey 1 2009 Survey 2 2011 $10M - S49M 3 1 $50M - $99M 2 3 $100M - $499M 6 2 $500M - $999M 3 4 $1B - $9B 15 7 $10B - $49B 12 15 $50B - $99B 3 3 Over $100B 2 3 Total 46 38 t-test (p = 0.25). Open Access AJIBM  ISO 31000:2009 Enterprise and Supply Chain Risk Management: A Longitudinal Study 619 Table 4. Employment profile. Employees Survey 1 2009 Survey 2 2011 Under 50 1 0 50 - 99 1 1 100 - 499 4 3 500 - 999 2 2 1000 - 4999 10 6 5000 - 9999 4 3 Over 10,000 24 23 Total 46 38 t-test (p = 0.48). Table 5. Ownership. Ownership Survey 1 2009 Survey 2 2011 Privately Owned 13 11 Publicly Owned 30 25 Public/Privately Owned 3 2 Total 46 38 t-test (p = 0.87). Table 6. Respondent titles. Title Survey 1 2009 Survey 2 2011 Supply Chain Leader/Manager /C oordinat or/Buyer 66% 54% Production/Operations/Materials Manager 22% 29% Analyst 6% 17% Account/Sales Director 6% 0 SCRM Process Survey data were grouped according to ISO 31000 Clause 5 process segments. The data tables are sorted by the highest mean score or the highest ranking based on survey two data. “Agree/disagree” questions were scaled from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree”. “Extent of use” questions were scaled from “1 = not used” to “7 = extensively used.” Communication and Consultation Clause 5.2: There were no statistically significant differences in the com- munication and consultation practices (Table 7). Infor- mation gathering and establishing communications with suppliers remain paramount approaches. However, con- cerns exist whether supply risk information is accurate and readily available. There may be a somewhat in- creased use of data warehousing and demand signal re- positories, though neither change was statistically sig- nificant. Establishing the Context Clause 5.3: Contextual fac- tors were grouped according to need, approach, budget, and organization (Table 8), consistent with general guidelines proposed by ISO 31000. There was a statisti- cally significant increase in the recognition that much can go wrong in a supply chain without systematic risk analysis. SCRM is recognized as a strategic issue, but the lack of a single set of tools or technologies makes im- plementation a challenge. The supply chain organization seems to lack key risk management skills and has a lim- ited understanding of corporate risk management strat- egy. SCRM budgets are shown in Table 9. The response rate was not 100% for this question due to competitive con- cerns. There was no significant difference in spending plans between the two data sets. Table 10 indicates that Open Access AJIBM  ISO 31000:2009 Enterprise and Supply Chain Risk Management: A Longitudinal Study 620 Table 7. SCRM and Clause 5.2 communication and consultation. Survey 1 2009 Survey 2 2011 t-test Item Mean SD Mean SD p Establishing good communications with suppliers 5.65 1.04 5.81 1.05 0.49 Information gathering 5.67 1.21 5.51 1.54 0.61 Forecasting techniques (e.g., to pre-build & carry additional inventory of critical items) 4.61 1.57 4.79 1.56 0.60 Our company uses real-time inventory information and analytics in managing the supply chain.4.76 1.52 4.61 1.66 0.68 Data warehousing 4.09 1.76 4.59 1.54 0.16 Visibility (detailed knowledge of what goes on in other parts of the supply chain—e.g., finished goods inventory, material inventory, WIP, pipeline inventory, actual demands and forecasts, production pl ans, capacity, yields, and order status) 4.26 1.29 4.24 1.46 0.95 Demand signal repositories 3.42 1.85 3.95 1.68 0.18 Supply chain risk information is accurate and readily available to key decision makers. 3.87 1.57 3.81 1.68 0.87 Network design analysis programs 3.25 1.94 3.41 1.40 0.68 Table 8. SCRM and Clause 5.3 establishing the context. Item Survey 1 2009 Survey 2 2011 t-test NEED Mean SD Mean SD p Without a systematic analy s is technique to a sse ss risk, much can go wrong in a supply chain.5.54 1.03 6.19 0.97 0.00* Managing supply chain risk is an increasingly important initiative for our operations. 5.65 1.30 5.92 1.19 0.33 It is critical for us to have an easily understood method to identify & manage supply chain risk.5.30 1.23 5.27 1.52 0.91 My workplace plans on evaluating or implementing supply chain risk tools and techn ologies.4.98 1.58 5.08 1.91 0.79 We are very concerned about our supply chain resiliency, and the failure implications. 4.78 1.59 4.81 1.65 0.94 APPROACH There is no single set of tools or technologies on the market for managing supply chain risks.5.24 1.49 5.50 1.34 0.41 We are currently using some form of supply chain r i s k management tools and services. 4.46 1.93 5.03 1.83 0.17 Managing supply chain risks is driven by reactions to failures rather being proactively driven.4.39 1.36 4.19 1.67 0.57 Proactive risk mitigation efforts applied to the supply chain is common practice for us. 4.33 1.49 4.19 1.76 0.71 Supply chain risk initiatives are driven from the bottom up rather than top down. 3.67 1.56 3.70 1.75 0.94 BUDGET We do plan on investing nontrivial amounts in managing supply chain risks. 4.30 1.86 4.17 1.46 0.71 We have a dedicated budget for activities associated with managing supply chain risks. 3.65 1.96 3.89 2.27 0.61 Funding for managing supply cha in r isks will come from a general operations budget. 3.91 1.94 3.81 2.03 0.81 Our spending intentions for managing supply chain risks are very high. 3.37 1.58 3.08 1.54 0.41 ORGANIZATION Supply chain employees understand government legislation & geopolitical issues. 3.70 1.26 3.73 1.61 0.92 I fully understand the activities being performed by our risk management group. 4.00 1.86 3.70 1.54 0.43 My workplace uses supply chain risk managers who work closely with corporate risk mgmt.2.53 1.74 2.64 1.81 0.79 We are planning to outsource all or some of our risk management functions. 2.25 1.28 2.14 1.22 0.69 Open Access AJIBM  ISO 31000:2009 Enterprise and Supply Chain Risk Management: A Longitudinal Study 621 Table 9. SCRM budget. Spend Survey 1 2009 Survey 2 2011 Less than $500,000 21 16 $1,000,000 - $5,000,000 3 3 $500,000 - $1,000,000 1 1 More than $5,000,0 00 3 4 Total 28 24 t-test (p = 0.50) Table 10. Projected change in SCRM budget. Change Survey 1 2009 Survey 2 2011 Increase 20 14 Decrease 6 3 No change 17 21 Total 43 38 t-test (p = 0.23) Table 11. Ownership of SCRM investments. Department Survey 1 2009 Survey 2 2011 Risk Managemen t 0 1 Supply Chain/Purchasing 40 33 Legal 0 0 Logistics 1 0 Manufacturing/Operations 2 1 IT 0 1 Accounting/Finance 1 1 Quality 0 0 Other 0 0 Total 44 37 t-test (p = 0.99) most firms will keep SCRM spending at current levels or increase spending in the future. Table 11 suggests that purchasing/supply generally takes ownership of SCRM investment s, t h ou g h Table 12 suggests the SCRM budget generally does not come from a specific SCRM budget. Risk Assessment Clause 5.4: There were no statistic- cally significant differences in the risk assessment prac- tices (Table 13). Specific risk factors such as supplier reliability, relocating facilitie s overseas and filling spikes in demand are carefully assessed. A relatively small per- centage of firms anticipate that they will exploit risk to Table 12. SCRM funding source. Source Survey 1 2009 Survey 2 2011 General operations budget 12 9 General IT budget 1 2 Specific departmental budget 20 14 General finance budget 5 2 Specific budget to address supply chain issues 8 11 Total 46 38 t-test (p = 0.55) an advantage by taking calculated supp ly chain risks. Respondents identified the top five risks that they face (Table 14). The most persistent risks seem to be supplier failure/reliability, supplier bankruptcy, commodity cost volatility, natural disaster, logistic failures and geopoliti- cal events. Respondents were also asked which risks would decrease, remain the same, or increase during the next two years (Table 15). Some of the highest-rated risk factors such as currency exchange rates and government regulations require that SCRM be integrated with ERM in order to most effectively treat the risk. Risk Treatment Clau se 5.5: There were no statistically significant differences in the risk treatment practices (Table 16). When risk is accepted, inventory manage- ment and buffering is a widely used option. Risk reduce- tion emphasized using approved suppliers, while risk sharing emphasized supplier partnering and develop- ment. Monitoring and Review Clause 5.6: There was a statis- tically significant increase in the monitoring and review practice of using credit and financial data analysis (Table 17). Firms extensively monitor supply chain and SCRM performance using a variety of techniques such as meas- urement systems, supplier visits, and supplier process monitoring. Relatively few firms benchmark SCRM processes to those of competitors. Firms appear to be somewhat satisfied with supply chain performance (Ta- ble 18). There was a statistically significant decrease in satisfaction with damage free and defect free delivery, and a statistically significant increase in satisfaction with reduced material price volatility. 5. Discussion The following research limitations should be kept in mind as the data are interpreted and discussed. The sam- ple size was by design relatively small to ensure a rela- tively high response rate and to secure participation in following-up interviews. Future research should consider a larger sample. The research findings are based on per- ceptual data, and while comon to survey work, future m Open Access AJIBM  ISO 31000:2009 Enterprise and Supply Chain Risk Management: A Longitudinal Study 622 Table 13. SCRM and Clause 5.4 risk assessment. Survey 1 2009 Survey 2 2011 t-test Risk Assessment Practices and Issues Mean SD Mean SD p Supplier reliability and continuous supply is the top risk factor for our supply chain. 5.35 1.34 5.68 1.43 0.29 Risks of moving manufacturing facilities overseas are carefully evaluated. 5.65 1.15 5.30 1.63 0.27 Risks of not being able to fulfill a spike in consumer dem and are carefully evaluated. 5.22 1.25 5.11 1.49 0.72 Key metrics are in place to measure the risk associated with key suppliers. 4.65 1.68 4.68 1.60 0.95 We apply high levels of analytical rigor to assess ou r supply chain practices. 4.37 1.53 4.38 1.78 0.98 A key part of our supply chain management is documenting the likelihood & impact of risks.4.20 1.67 4.19 1.60 1.00 Taxes such as excise and VAT impact our supply chain decisions. 3.86 1.69 4.05 1.73 0.62 We can actually exploit risk to an advantage by taking ca lculat ed risks in the supply chain. 4.02 1.63 3.97 1.64 0.89 Table 14. Current supply chain risks. Frequency Risk Factor Survey 1 2009 Survey 2 2011 Supplier failure/reliability 41 33 Bankruptcy, ruin, or default of suppliers, shippers, etc. 22 19 Commodity cost volatility 18 15 Natural disasters or accidents (tsunamis, hurricanes, fires, etc.) 15 14 Logistics failure 20 12 Geopolitical event (terrorism, war, etc.) 6 10 Contract failure 4 8 Strikes—labor, buyers and suppliers 15 8 Customer-related (demand change, system failure, payment delay) 8 8 Energy/raw material shortages and power outages 6 8 Information delays, scarcity, sharing, & infrastructure breakdown 5 6 Government regulations (SOX, SEC, Clean Air Act, OSHA, EU) 9 5 Intellectual property infringement 7 5 Lack of trust with partners 7 5 Diminishing capacities (financial, production, structural, etc.) 10 5 Contamination exposures—food, germs, infections 3 5 Legal liabilities and issues 5 4 Return policy and product recall requirements 2 4 Attracting and retaining skilled labor 8 4 Currency exchange, interest, and/or inflation rate fluctuations 7 4 research should include objective measures (e.g., actual risk reduction outcomes, actual budget, etc.). Responses came mostly from manufacturing firms and future re- search should include a greater number of service firms to increase generalizability. Also, the decision to obtain ISO 31000 registration is not always straightforward for managers since many is- sues still surround the ERM standard. Although ISO Open Access AJIBM  ISO 31000:2009 Enterprise and Supply Chain Risk Management: A Longitudinal Study 623 Table 15. Projected change in supply chain risks. Survey 1 2009 Survey 2 2011 Risk Category LessSame More Less Same More Currency exchange, interest, and/or inflation rate fluctuations 0 7 36 1 3 34 Commodity cost volatility 2 9 33 4 6 28 Banking regulations and tighter financing conditions 1 16 28 2 9 27 Government regulations (S OX, SEC, Clean Air Act, OSHA, EU) 0 28 16 0 14 24 Supplier failure/reliability 13 7 24 7 14 17 Geopolitical event (terrorism, war, etc.) 0 29 15 0 22 16 Energy/raw material shortages and power outages 3 26 15 1 21 16 Customs Acts/Trade restrictions and protectionism 2 27 16 3 19 16 Logistics failure 8 27 9 5 17 16 Bankruptcy, ruin, or default of suppliers, shippers, etc. 2 13 29 6 16 16 Customer-related (demand change, system failure, payment delay) 3 22 19 2 21 15 Diminishing capacities (financial, production, structural, etc.) 5 22 17 5 18 15 Return policy and product recall requirements 5 29 9 1 23 14 Port/cargo security (information, freight, vandalism, sabotage, etc.) 3 29 13 1 24 13 Legal liabilities and issues 2 26 17 1 24 13 Insurance coverage 1 29 14 0 26 12 Tax issues (VAT, transfer pricing, excise, etc.) 3 32 9 0 27 11 Natural disasters or accidents (tsunamis, hurricanes, fires, etc.) 2 34 12 1 26 11 Intellectual property infringement 3 23 18 1 28 9 Attracting and retaining skilled labor 12 15 16 7 22 9 Language and educational barriers 8 21 15 11 18 9 Strikes—labor, buyers and suppliers 4 26 14 4 26 8 Property development —local codes and requirements 4 35 6 1 30 7 Unfamiliar business and pr operty laws 6 36 3 2 29 7 Weaknesses in the local infrastructures 9 27 8 5 26 7 Contract failure 5 32 7 6 25 7 Contamination exposures—food, germs, infections 5 37 2 3 29 6 Ethical issues (working practices, health, safety, etc.) 8 30 7 5 27 6 Obtaining proper bonds & licenses 6 35 3 3 30 5 Degree of control over operations 8 30 6 10 23 5 Measuring tools—metrics translate differently 10 27 7 8 26 4 Lack of trust with partners 13 24 7 10 24 4 Internal and external theft 4 36 5 3 32 3 Fraud or scandal 3 34 7 3 32 3 Information delays, scarcity, sharing, & infrastructure breakdown 18 18 8 15 20 3 Open Access AJIBM  ISO 31000:2009 Enterprise and Supply Chain Risk Management: A Longitudinal Study 624 Table 16. SCRM and Clause 5.5 risk treatment. Survey 1 2009 Survey 2 2011 t-test Treatments Mean SD Mean SD p ACCEPTANCE Inventory management (buffers, safety stock levels, optimal order & production qty.) 4.96 1.69 5.42 1.08 0.13 Contingency Planning (jointly with suppliers) 4.22 1.25 4.63 1.50 0.18 We have placed an increased focus on inventory management to deal with supply risks. 4.80 1.34 4.56 1.46 0.43 Our suppliers are required to have secure sourcing, business continuity, & contingency plans.4.62 1.71 4.54 1.86 0.84 We are prepared to minimize the effects of disruptions (terrorism, weather, theft, etc.) 3.70 1.31 3.86 1.87 0.64 REDUCTION Using an approved list of suppliers 5.78 1.18 6.11 1.11 0.20 Multiple sourcing (rather than sole sourcing) 4.04 1.36 4.47 1.72 0.22 Postponement (delaying the actual commitment of resources to maintain flexibility) 3.70 1.35 3.97 1.30 0.34 SHARING Partnership formation and long-term agreements 5.11 1.08 5.24 1.15 0.60 Supplier development initiatives 4.83 1.37 5.18 1.41 0.24 Speculation (forward placement of inven tory, forward buying of raw m aterial, etc.) 4.07 1.69 4.08 1.38 0.97 Hedging strategies (to protect against commodity price swings) 3.61 1.63 3.92 1.62 0.38 We are hedging our raw materials exposure to reduce input cost volatility. 3.78 1.49 3.65 1.69 0.72 Joint technology development initiatives 3.59 1.47 3.47 1.89 0.76 Table 17. SCRM and Clause 5.6 monitoring and re view. Survey 1 2009 Survey 2 2011 t-test Process Mean SD Mean SD p Supplier performance measurement systems 5.35 1.61 5.71 1.64 0.31 Credit and financial data analysis 4.54 1.60 5.37 1.34 0.01 * Visiting supplier operations 5.04 1.32 5.34 1.24 0.29 Business process manageme nt 4.65 1.37 5.11 1.27 0.12 Consistent monitoring and auditing of a supplier’s processes 4.59 1.72 5.03 1.68 0.24 Spend managem ent and analysis 4.85 1.53 5.03 1.70 0.62 Contract management (e.g., levera ge tools to monitor performance against commitments)4.48 1.64 5.00 1.52 0.14 Benchmarking (internal, external, industry-wide, etc.) 4.59 1.54 4.68 1.51 0.77 We have placed an emphasis on in cident reporting to decrease the effects of disruptions. 4.50 1.43 4.49 1.76 0.97 Inventory optimization tools 4.78 1.66 4.49 1.68 0.43 Training programs 3.54 1.59 3.79 1.66 0.49 We use network design and optimization tools to cope with uncertainty in the supply chain.3.66 1.85 3.67 1.64 0.98 We actively benchmark our supply chain risk processes against competitors. 3.57 1.68 3.39 2.02 0.67 Open Access AJIBM  ISO 31000:2009 Enterprise and Supply Chain Risk Management: A Longitudinal Study Open Access AJIBM 625 Table 18. Performance satisfaction. Survey 1 2009 Survey 2 2011 t-test Outcome Mean SD Mean SD p Logistics and delivery reliability 4.96 1.01 5.32 1.25 0.15 Meeting customer service levels 5.07 1.20 5.19 1.17 0.64 Supplier reliability and continuous supply 4.85 0.99 5.03 1.12 0.45 Damage-free and defect-free de livery 5.41 0.83 5.00 0.94 0.04* Order completeness and correctness 4.96 1.11 4.86 1.29 0.73 After sales service performance 4. 57 1.29 4.86 1.09 0.27 Inventory management 4.52 1.22 4.84 1.32 0.27 Reduced disruptions in the supply chain 4.59 1.15 4.54 1.07 0.85 Reduced material price volatility 3.80 1.51 4.32 1.06 0.07* Lower commodity prices 3.98 1.27 4.05 1.20 0.78 31000 addresses several criticisms of previous ERM frameworks [8,21-23], it is still met with uncertainty and this uncertainty could have impacted the survey findings. Most of this uncertainty is related to perceived weak- nesses with regard to its ability to deliver real benefits and a continued over-emphasis on bureaucratic processes and documentation. Other criticisms generally concern inappropriate misapplication or extension of its use in companies, and the effect this can have on organizational resources and culture. While the criticism focuses on the standard, the problems typically arise from a failure of organizations to understand the underlying philosophy of the standard and the idea, which is a process-driven sys- tematic approach to ERM. 5.1. Longitudinal Data Analysis and SCRM Trends The primary reason for using longitudinal data was to determine if over time the ISO 31000 framework pro- vided a foundation for both researchers and managers to discuss, examine, and/or implement SCRM strategies and practices. There is a reasonable alignment between proposed SCRM frameworks, actual SCRM practices and ISO 31000:2009. So, if it is true that adopting a con- sensus framework for SCRM research will enable better communication between researchers an d practitioners, so that such a common framework would enable more effi- cient and effective research to close research gaps [7], then ISO 31000:2009 provides a reasonable foundation. A secondary reason for employing longitudinal data was to identify trends in supply risks, strategies, and practices. There were only four statistically significant changes identified. There was an increase in agreement that without a systematic analysis technique to assess risk, much can go wrong in a supply chain. As will be dis- cussed subsequently, it doesn’t appear that this awareness has translated into SCRM being raised to a strategic cor- porate level through linkages with ERM, or into an in- creased allocation of resources for SCRM. ISO 31000 may provide a foundation for practitioners to remedy those situations. There was a statistically significant increase in the use of credit and financial data analysis, likely driven by the high level of supplier failures and bankruptcies over the last decade. Firms reported statistically significant better performance in terms of reducing material price volatility. It is not possible to identify specific drivers of this im- proved performance without controlling for many broad economic factors. Hedging strategies were not widely used, so this is unlikely a driver. Perhaps the relatively high use of supplier partnering, approved supplier lists and increased use of supplier financial health assessment helped create some price stability. There was a decrease in satisfaction with damage-free and defect-free delivery performance. Again, the direct causes of this outcome are not readily identifiable. The examination of direct cause and effect relationships was beyond the scope of this research. It was also clear that some of the survey re- sponses were linked to the economic recession conditions of 2008. For example, a major risk and source of supply chain disruption was supplier bankruptcy, for which most buying organizations were not proactively evaluating. Future research should explore such relationships and over a period of time that goes beyond the two years covered in t his study to see how com panies h ave managed this and other risk issues since.  ISO 31000:2009 Enterprise and Supply Chain Risk Management: A Longitudinal Study 626 5.2. SCRM Practices Relative to ISO 31000 Clauses Clause 5.2 Communication and Consultation: The impor- tance of reliable and timely information communicated throughout the value chain was evident. One manager highlighted this importance: “We have a very intricate web of parts supply. It can be very difficult to get accu- rate information about our suppliers and even our own company overseas. Many times, it is difficult to know where to obtain information accurately and reliably. So, even if we have a perfect system or structure in place to manage risk, it depends on the input of reliable data that accurately identifies the risk. The old “garbage in/gar- bage out’ theory applies.” Not only was the ability to find reliable information a challenge for some firms, the ability to sh are information quickly was also a challenge. One manager noted that the major failure mode was “information speed that is too reactive versus proactive.” Some firms indicated that such challenges can be overcome by matching informa- tion research efforts with project needs: “In many cases getting good information can be as simple and cheap as subscribing to a few periodicals, or as complex and ex- pensive as hiring outside consultants. It really depends on the business that you’re in and the needs of the com- pany.” Clause 5.3 Establishing the Context: Proposed SCRM frameworks as well as SCRM strategies and practices used by respondents align well with the ISO 31000 proc- ess. However, it does not appear that the firms are proac- tively using ISO 31000 or any other such integrative framework for SCRM. Even at firms with seemingly advanced SCRM practices, the linkage to ERM seems a bit weak. One manager stated that “supply risk manage- ment is handled at the plant location level and not from the corporate level. This is created by a ‘we have always done it this way’ mentality. It has always worked in the past because changes to production plans have never fluctuated like this before, both up and down. This chal- lenge is preventing us from accurately assessing which suppliers are at risk and why, and assessing this early enough to do something about it.” ISO 31000 states that upper managers need to take the lead in ERM and SCRM to establish the appropriate cul- ture, organization, budget, resources, and processes for managing risks. A few respondents suggested that their firms have recently taken steps in this direction, as ex- emplified by one manager’s comment: “Resources have been allocated to SCRM as we have increased the amount of Full Time Headcount dedicated to supply chain activities across the company. We have also re- ceived IT prioritization for projects that will help us un- derstand exposure related to certain supply relationships and allow us to take action on those. As we continue to broaden our business and create revenue streams gener- ated from 100% supplied product, we have a more direct association of revenue risk with the supply chain.” Such strategic linkage of SCRM to ERM was not uni- versal. When support from upper management was lack- ing, most respondents suggested that it was up to the supply group to make a solid business case for SCRM, as summarized by one manager: “As supply managers, we need to have an effective way to tie a supplied produ ct or component back to actual revenue generated from that product or component. Many companies including ours need to make the process easier and more visible to up- per management once the data is retrieved. The finan- cial impact—favorable or unfavorable—as well as the fi- nancial risk and exposure should be captured by the sup- ply managers and communicated up through upper man- agement.” The lack of SCRM linkage to ERM is further evi- denced in the organization section of Table 8. Few sup- ply personnel understand government legislation, geopo- litical issues, or the activities being performed by the firm’s risk management group. Perhaps supply chain curriculum nee ds to put a greater em phasis on suc h issues, or companies need to hire supply personnel with more varied experiences and backgrounds. Despite “non-trivial” amounts being spent on SCRM and most firms increasing the budget for SCRM, the overall perspective was that budgets were not sufficiently “high.” Supply managers suggested that their ability to mitigate supply chain risks was often limited by a lack of money, time, or people. The current business environ- ment and focus on lean operations suggested that secure- ing more resources for SCRM is now even more chal- lenging. One manager stated: “In the current state of the economy with pressure for reduced cost and leaner man- ufacturing, it’s harder to have the resources—people and funding—to be fully prepared for these risks, which greater puts a company in the face of danger.” As stated earlier, it is up to the supply manager to make a busin ess case for SCRM. Perhaps it is the failure to make a busi- ness case that explains why the budget for SCRM most often is established in departments other than supply. Relatively few firms indicated that their company takes a proactive risk management approach. The firms that had this perspective recognized that communications and involvement with upper management was the key: “Our top management has a reoccurring meeting where various plants get together and discuss suppliers that are putting our business at risk. Sources of risk can be financial—bankruptcy, paying sub suppliers, resources and capacity risk, or price risk. Meeting on these issues frequently allows top management to be aware of the issues and adjust business outlooks if needed.” Clause 5.4 Risk Assessment: Most firms identify a Open Access AJIBM  ISO 31000:2009 Enterprise and Supply Chain Risk Management: A Longitudinal Study 627 wide range of risks and then prioritize those risks in terms of potential impact and/or likelihood of occurrence. One manager cautioned that focusing on high priority risks makes good sense, but perhaps it is the interaction of multiple moderate risks that in combination result in the most significant risk. Future research might examine the use of “design of experiments” to assess risk. The most frequently cited and persistent risk factor was supplier failure/reliability. Some firms recognized that part of the problem is their own doing. One manager commented that “the automotive industry and their ne- gotiating techniques have ruined and shut down suppliers. The cost pressures are immense in today’s economy, forcing customers to squeeze their suppliers.” Future re- search may explore the impact that internal company processes (e.g., lean initiatives, cost reduction or target costing programs, product variety and proliferation) have on creating supply risks. Quite a few of the most frequently cited and increasing risk factors are beyond the control of supply managers (e.g., natural disasters, geopolitical events, increasing go- vernment regulations, currency fluctuations, etc.). Com- panies tend to treat such risks using dual sourcing or buffer inventories. Somewhat surprising was that fewer firms used hedging strategies or speculation techniques. Perhaps this was due to the lack of supply personnel un- derstanding such issues as previously discussed. Clause 5.5 Risk Treatment: Partnerships were exten- sively used to share risks, though few firms used joint te- chnology development to share risk. This is somewhat surprising because it is generally agreed that risk man- agement is most efficient and effective when done early in a product lifecycle. Given an increasing focus on “open innovation” in the last decade, perhaps more firms will partner not only for innovation but for risk reduction as well during new product development. One manager commented that this will be a challenge because SCRM analysis takes time and anything that might hold up new product development time is unlikely to be implemented. Companies rely extensively on qualification of ap- proved suppliers to reduce risks. One manager com- mented that such lists are important, but the assessments are generally based on past performance and may not be indicative of future performance. Forward-looking risk assessment measures tended to be limited and very sub- jective. One respondent indicated that forward looking measures such as supplier scalability (e.g., supplier abil- ity to develop global reach) and supplier-supply chain management skills (i.e., supplier’s ability to manage its own supply chain ) needed to be includ ed in supp lier qua- lification systems to prevent future risks. Clause 5.6 Monitoring and Review: Without ongoing monitoring and control, supplier performance may de- grade after qualification, and then risks will surface over time. Companies monitor and control SCRM and supply chain performance using traditional performance meas- ures such as cost, quality, delivery, etc. Though SCRM impacts such performance outcomes, most firms would like to develop risk specific measures to help them make the business case for more investments in SCRM. One manager commented: “I think we could have more clear-cut metrics that are directly related to supply chain risk, rather than some of the indirect ones that we have now. But to create new metrics always requires funding, which at this time isn't being used for more metric de- velopment.” In the meantime, firms will continue to mo- nitor performance by conducting traditional supplier vis- its and using supp lier scorecards. Without knowing in ad- vance how to measure SCRM strategy performance, one option is to adopt a learning organization perspective as suggested by one manager: “I’m not sure we have an official way of reviewing if a risk strategy was as effect- tive as others. If we avoided a risk, we consider that a success. If we still got exposed to a risk despite our stra- tegy, we’ll review lessons learned and then adjust the strategy to incorporate th at.” Supply managers are rarely compensated specifically for SCRM efforts, in part due to the difficulty of proving that without risk treatment the result would have been worse. Compensation for “risk management” is generally based on traditional supply chain performance measures and one manager stated: “Risk performance evaluation is tracked through the review process, and performance ratings are given based on performance to key objectives. Employees also receive a bonus based on actual business performance—we reduce risk, business performance is strong.” In most cases however, there was no specific bo- nus or compensation for risk management: “Typically the people working on risk management are the same people working with the suppliers on a daily basis, so no further compensation is given. At a global supply chain man- agement level, risk management is a larger part of their day-to-day responsibilities, but more from a coordination of efforts level than a working level, and still no addi- tional compensation .” Respondents seemed relatively satisfied with supply chain performance along multiple dimensions, thoug h all respondents recognized the need for continuous improve- ment. Some progress was made in controlling price vo la- tility as previously discussed. Again, whether or not these performance outcomes can be directly tied to SCRM is unclear. 5.3. Implications for Managers The findings suggest that firms are very concerned about supply chain risks and that they spend significant effort managing those risks. However, it doesn’t seem that firms take a long-term approach to SCRM by integrating Open Access AJIBM  ISO 31000:2009 Enterprise and Supply Chain Risk Management: A Longitudinal Study 628 such efforts with ERM, and that making a business case for SCRM will remain a challenge. One manager stated: “We don’t have a dedicated set of resources for risk management. We take the approach that it’s everyone’s responsibility. Good in theo ry, but during very busy parts of the year, other commitments may take the focus off risk management, thus leaving us open to issues. The challenge in creating a dedicated group to manage this is always money. Is it worth it? To overcome this, you’d need to look at the cost of the resources, people, and technology and balance that against the costs that are avoided by having the group in place. This calculation would likely involve a lot of soft costs and could be dif- ficult to get agreement on, thu s making it a tough er sell.” This perspective was shared by many respondents to our survey. Given that SCRM efforts map well to the ISO 31000 stand ard, perh aps supply managers will be able to strengthen the business case for SCRM and create a linkage of SCRM to ERM by deploying the “missing link,” the ISO 31000 standard. 5.4. Implications for Researchers A few future research topics were already presented in the discussion section. For example, research that in- cludes service purchases and/or service firms is war- ranted. The exploration of direct cause-and-effect rela- tionships is also of interest (e.g., what is the best re- sponse to a parts shortage caused by a hurricane versus a parts shortage driven by limited supply capacity?). A suggestion was also made th at examining the impact and treatment of the interaction of risks might advance our understanding of SCRM. Further, research regarding the impact of buying firm strategy and process (e.g., lean initiatives, cost reduction, product proliferation) on driv- ing supply risks was suggested. The following topics expand on such issues. Topic 1: Can our understanding of SCRM be sup- ported and accelerated by adoption of the ISO 31000 framework? The literature review suggested that ISO 31000 is more comprehensive than current SCRM frameworks, that SCRM is considered a subset of ERM [7], and that ISO 31000 may become an internationally implemented ERM standard [26]. Perhaps SCRM re- searchers should ad opt the ISO 31000 framework so that agreement on definitions, terms, scales, etc., will be reached to support in-depth SCRM research. Topic 2: Does ERM/SCRM provide approp riate return on investment? Firms with well established SCRM strategies and structures respond more effectively, at least in the short term, to major supply disruptions than firms without such structures. However, such significant disruptions tend to be rare. It has been suggested that different structures and approaches to SCRM provide different results. For example, one effort found that SCRM implementation impacts supply performance, but reactive SCRM provided better disruption resilience and reduction of the bullwhip effect while preventive SCRM provided better values concerning flexibility and safety stocks [52]. Ultimately, does an established department, system, and resources dedicated to SCRM pay for itself in the long term, and if so, what is the appropriate struc- ture? Topic 3: Related to Topic 2, what is the most effective organizational structure for effective SCRM? Initiatives such as Six Sigma have called for different levels of spe- cialization (e.g., black and green belts), yet they still maintained that quality is the responsibility of each per- son. Even lean initiatives call for a somewhat hierarchi- cal structure of expertise (e.g., group leader, team leader), yet they maintained that waste reduction and flow are everybody’s responsibility. Should a separate SCRM department be created, or should it be part of the ERM organization? Should a hierarchical structure of risk ex- perts be developed, or should SCRM be part of each supply person’s everyday responsibilities? Or, perhaps the most effective SCRM approach would be to out- source it. The increased use of 3PL/4PL, supply chain consultants, information brokers and analysts such as D&B, government or industry regulations (e.g., GAAP, SOX, etc.) and international standards (e.g., ISO 9000, ISO 14000) already provide support for SCRM out- sourcing. Topic 4: To what extent should SCRM be integrated into new product development efforts? Collaboration with suppliers for new product development has in- creased in the past decade. A primary objective of such efforts is to innovate, but part of all su ch processes are to address technology risks early. How can firms most ef- fectively “design for supply risk” without delaying new product development efforts. Perhaps the “rapid plant assessment” process [53] provides a good starting point for a “rapid risk assessment” process. Topic 5: What is the role for IT, and how can compa- nies more efficiently integrate new IT to support SCRM? This research suggested that firms use IT for SCRM by gathering and disseminating data, communicating with suppliers, measuring performance, and managing invent- tory. However, few firms used IT for SCRM by creating data warehouses, integrating supplier into new product development, analyzing network designs analysis, or optimizing inventory. Advancements in IT applications, including for example cloud computing, tablets and mo- bile devices, enable firms to gather and distribute real- time data. Research that identifies proper strategies for the use and effective adoption of such tools is warranted. 6. Acknowledgements The authors would like to take this opportunity to thank Open Access AJIBM  ISO 31000:2009 Enterprise and Supply Chain Risk Management: A Longitudinal Study 629 the following Western Michigan University undergradu- ate students for their participation in this research project: Mr. Jamie A. Loeks, Mr. Judson A. McCulloch, and Ms. Priyanka Parekh. REFERENCES [1] D. Wu, D. Olson and J. Birge, “Introduction to Special Issue on ‘Enterprise Risk Management in Operations’,” International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 134, No. 1, 2011, pp. 1-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2011.07.002 [2] R. Hoyt and A. Liebenberg, “The Value of Enterprise Risk Management,” Journal of Risk and Insurance, Vol. 78, No. 4, 2011, pp. 795-822. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6975.2011.01413.x [3] C. Smithson and B. Simkins, “Does Risk Management Add Value? A Survey of the Evidence,” Journal of Ap- plied Corporate Finance, Vol. 17, No. 3, 2005, pp. 8-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6622.2005.00042.x [4] M. Beasley, R. Clune and D. Hermanson, “ERM: A Sta- tus Report,” The Internal Auditor, Vol. 62, No. 1, 2005, pp. 67-72. [5] L. Hauser, “Risk Adjusted Supply Chain Management,” Supply Chain Management Review, Vol. 7, No. 6, 2003, pp. 64-71. [6] R. VanderBok, J. Sauter, C. Bryan and J. Horan, “Man- age Your Supply Chain Risk,” Manufacturing Engineer- ing, Vol. 138, No. 3, 2007, pp. 153-161. [7] M. S. Sodhi, B. G. Son and C. S. Tang, “Researcher’s Perspective on Supply Risk Management,” Productions and Operations Management, Vol. 21, No. 1, 2012, pp. 1-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-5956.2011.01251.x [8] R. Tummala and T. Schoenherr, “Assessing and Manag- ing Risks Using the Supply Chain Risk Management Pro- cess (SCRMP),” Supply Chain Management, Vol. 16, No. 6, 2011, pp. 474-483. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13598541111171165 [9] O. Tang and S. N. Musa, “Identifying Risk Issues and Research Advancements in Supply Chain Risk Manage- ment,” International Journal of Production Economic, Vol. 133, No. 1, 2011, pp. 25-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2010.06.013 [10] S. Black and L. Porter, “Identification of the Critical Factors of TQM,” Decision Sciences Journal, Vol. 27, No. 1, 1996, pp. 1-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.1996.tb00841.x [11] N. Capon, M. Kaye and M. Wood, “Measuring the Suc- cess of a TQM Programme,” International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management, Vol. 12, No. 8, 1994, pp. 8-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02656719510097471 [12] S. Curkovic, S Melnyk, R. Calantone and R. Handfield. “Validating the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Fram- ework Through Structural Equation Modeling,” Interna- tional Journal of Production Research, Vol. 38, No. 4, 2000, pp. 765-791. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/002075400189149 [13] J. Dean and D. Bowen, “Management Theory and Total Quality: Improving Research and Practice through Theory Development,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 19, No. 3, 1994, pp. 392-418. [14] B. Flyn n, R. Schro ede r and S. Sakakibara, “A Framework for Quality Management Research and an Associated In- strument,” Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 11, No. 4, 1994, pp. 339-366. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(97)90004-8 [15] V. Saraph, P. Benson and R. Schroeder, “An Instrument for Measuring the Critical Factors of Quality Manage- ment,” Decision Sciences, Vol. 20, No. 4, 1989, pp. 810- 829. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.1989.tb01421.x [16] B. Nocco and R. Stulz, “Enterprise Risk Management: Theory and Practice,” Journal of Applied Corporate Fi- nance, Vol. 18, No. 4, 2006. pp. 8-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6622.2006.00106.x [17] D. Bowling and L. Rieger, “Making Sense of COSO’s New Framework for Enterprise Risk Management,” Bank Accounting & Finance, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2005, pp. 35-40. [18] C. Chapman, “Bringing ERM into Focus,” The Internal Auditor, Vol. 60, No. 3, 2003, pp. 30-35. [19] B. Ballou and D. Heitger, “A Building Block Approach for Implementing COSO’s Enterprise Risk Manage- ment—Integrated Framework,” Management Accounting Quarterly, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2005, pp. 1-10. [20] A. Samad-Khan, “Why COSO Is Flawed,” Operational Risk, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2005, pp. 24-28. [21] J. Hallikas, I. Karvonen, U. Pulkkinen, V. M. Virolainen and M. Tuominem, “Risk Management Processes in Sup- plier Networks,” International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 90, No. 1, 2004, pp. 47-58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2004.02.007 [22] P. R. Kleindorfer and G. H. Saad, “Managing Disruptions in Supply Chains,” Production and Operations Manage- ment, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2005, pp. 53-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-5956.2005.tb00009.x [23] I. Manuj and J. T. Mentzer, “Global Supply Chain Risk Management,” Journal of Business Logistics, Vol. 29, No. 1, 2008, pp. 133-156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.2158-1592.2008.tb00072.x [24] M. Moody, “ERM & ISO 31000,” Rough Notes, Vol. 153, No. 3, 2010, pp. 80-81. [25] ISO, “ISO 31000:2009, Risk Management—Principles and Guidelines,” International Standards Organization, Geneva, 2009. [26] D. Gjerdrum and W. Salen, “The New ERM Gold Stan- dard: ISO 31000:2009,” Vol. 55, No. 8, 2010, pp. 43-44. [27] “AS/NZS. AS/NZS 4360:2004,” Risk Management Standard, Wellington, 2007. [28] ISO, “ISO Guide 73:2009, Risk Management—Vocabu- lary,” International Standards Organization, Geneva, 2009. [29] G. Purdy, “ISO 31000:2009—Setting a New Standard for Risk Management,” Risk Analysis, Vol. 30, No. 6, 2010, pp. 881-886. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01442.x Open Access AJIBM  ISO 31000:2009 Enterprise and Supply Chain Risk Management: A Longitudinal Study Open Access AJIBM 630 [30] J. Blackhurst, T. Wu and P. O’Grady, “PDCM: A Deci- sion Support Modeling Methodology for Supply Chain, Product and Process Design Decisions,” Journal of Op- erations Management, Vol. 23, No. 3-4, 2005, pp. 325- 343. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2004.05.009 [31] S. Kumar and J. Verruso, “Risk Assessment of the Secu- rity of Inbound Containers at US Ports: A Failure, Mode, Effects, and Criticality Analysis Approach,” Transporta- tion Journal, Vol. 47, No. 4, 2008, pp. 26-41. [32] Z. Liu and J. Cruz, “Supply Chain Networks with Corpo- rate Financial Risks and Trade Credits Under Economic Uncertainty,” International Journal of Production Eco- nomics, Vol. 137, No. 1, 2012, pp. 55-67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2012.01.012 [33] G. Zsidisin and J. Hartley, “A Strategy for Managing Commodity Price Risk,” Supply Chain Management Re- view, Vol. 1, No. 2, 2012, pp. 46-53. [34] G. Zsidisin and S. Wagner, “Do Perceptions become Re- ality? The Moderating Role of Supply Chain Resiliency on Disruption Occurrence,” Journal of Business Logistics, Vol. 31, No. 2, 2010, pp. 1-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.2158-1592.2010.tb00140.x [35] C. S. Tang, “Perspectives in Supply Chain Risk Man- agement,” International Journal of Production Econom- ics, Vol. 103, No. 2, 2006, pp. 451-488. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2005.12.006 [36] M. Laeequddin, G. D. Sardana, B. S. Sahay , K. Abdul Wa- heed and V. Sahay, “Supply Chain Partners Trust Building Process through Risk E valuation: The Perspective s of UAE Packaged Food Industry,” Supply Chain Management, Vol. 14, No. 4, 2009, pp. 280-290. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13598540910970117 [37] O. Khan and B. Burnes, “Risk and Supply Chain Man- agement: A Research Agenda,” The International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2007, pp. 197- 216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09574090710816931 [38] G. A. Zsidisin, L. M. Ellram, J. R. Carter and J. L. Cavinato, “An Analysis of Supply Risk Assessment Techniques,” In- ternational Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 34, No. 5, 2004, pp. 397-413. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09600030410545445 [39] K. Inderfurth and P. Kelle, “Capacity Reservation under Spot Market Price Uncertainty,” International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 133, No. 1, 2011, pp. 272- 279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2010.04.022 [40] M. Giannakis and M. Loui s, “A Multi-Agen Base d Frame- work for Supply Chain Risk Management,” Journal of Pu r- chasing and Supply Management, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2001, pp. 23-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2010.05.001 [41] E. Holschbach and E. Hofmann, “Exploring Quality Man- agement for Business Services from a Buyer’s Perspec- tive Using Multiple Case Study Evidence,” International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 31, No. 6, 2011, pp. 648-685. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01443571111131980 [42] D. Kern, R. Moser, E. Hartman and M. Moder, “Supply Risk Management: Model Development and Empirical Analysis,” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 42, No. 1, 2012, pp. 60-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09600031211202472 [43] C. Y. Chiang, C. Kocabasoglu-Hillmer and N. Suresh, “An Empirical Investigation o f the Impact of Strategic Sou rcing and Flexibility on Firms Supply Chain Agility,” Interna- tional Journal of Operations and Production Management, Vol. 32, No. 1, 2012, pp. 49-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01443571211195736 [44] S. Matook, R. Lasch and R. Tamaschke, “Supplier De- velopment with Benchmarking as Part of a Comprehen- sive Supplier Risk Management Framework,” Interna- tional Journal of Operations and Production Management, Vol. 29, No. 3, 2009, pp. 241-267. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01443570910938989 [45] M. Christopher, C. Mena, O. Khan and O. Yurt, “Ap- proaches to Managing Global Sourcing Risk,” Supply Chain Management, Vol. 16, No. 2, 2011, pp. 67-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13598541111115338 [46] K. Eisenhardt, “Building Theories from Case Study Re- search,” The Academy of Manage ment Review, Vo l. 14, No. 4, 1989, pp. 532-550. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1989.4308385 http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/258557 [47] C. Voss, N. Tsikriktsis and M. Frohlich, “Case Research in Operations Management,” International Journal of Op- erations & Production Management, Vol. 22, No. 2, 2002, pp. 195-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01443570210414329 [48] M. Miles and A. Huberman, “Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods,” Sage Publications, New- bury Park, 1984. [49] B. Glaser and A. Strauss, “The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualititative Reasearch,” Aldine, Chi- cago, 1967. [50] D. M. McCutcheon and J. R. Meridith, “Conducting Case Study Research in Operations Management,” Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 11, No. 3, 1993, pp. 239- 256. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0272-6963(93)90002-7 [51] J. S. Armstrong and T. S. Overton, “Estimating Nonre- sponse Bias in Mail Surveys,” Journal of Marketing Re- search, Vol. 14, No. 3, 1977, pp. 396-402. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3150783 [52] J. H. Thun and D. Hoening, “An Empirical Analysis of Supply Chain Risk Management in the German Automo- tive Industry,” International Journal of Production Eco- nomics, Vol. 131, No. 1, 2011, pp. 242-249. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2009.10.010 [53] R. E. Goodson, “Read a Plant—Fast,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 80, No. 5, 2002, pp. 105-113.

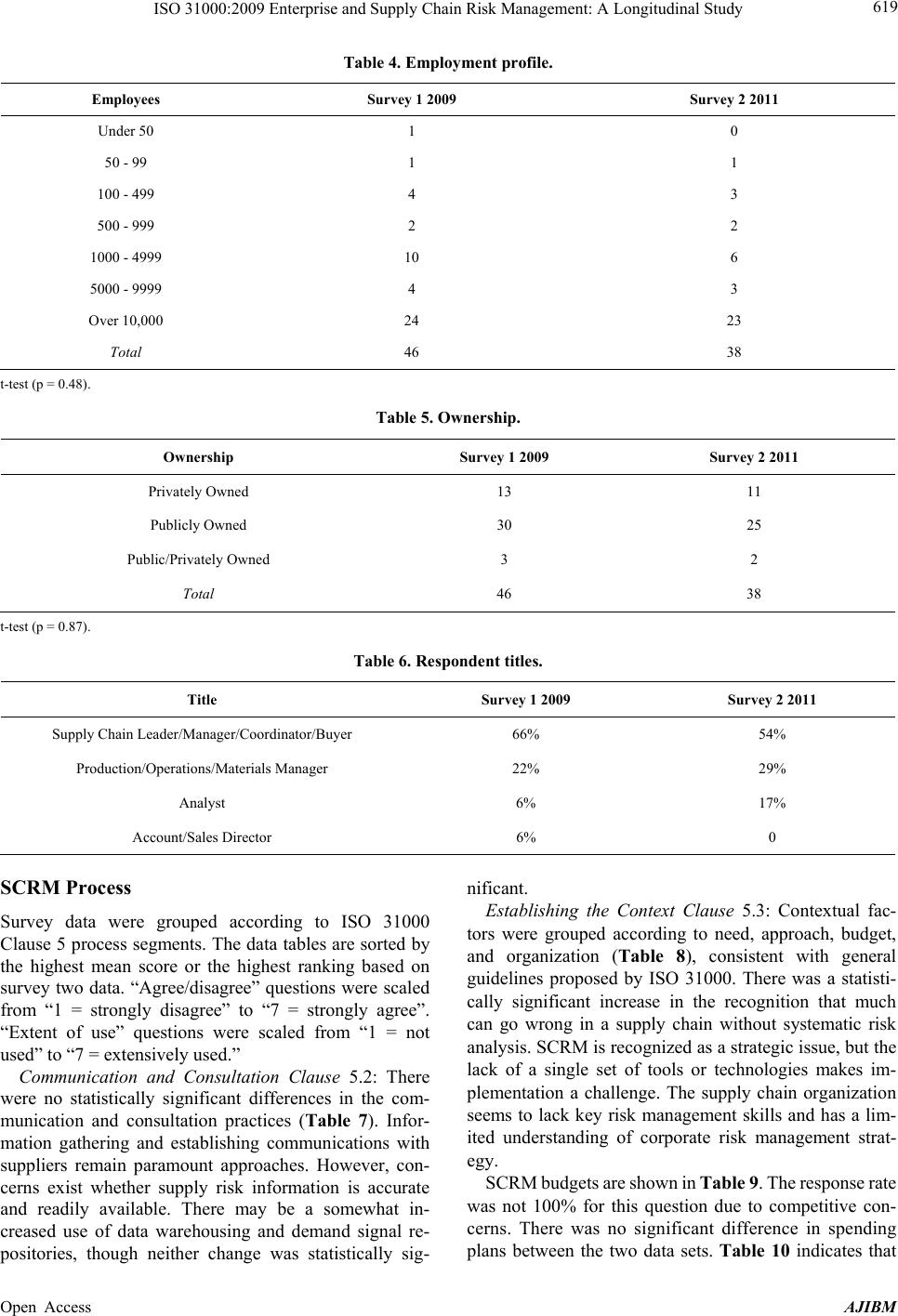

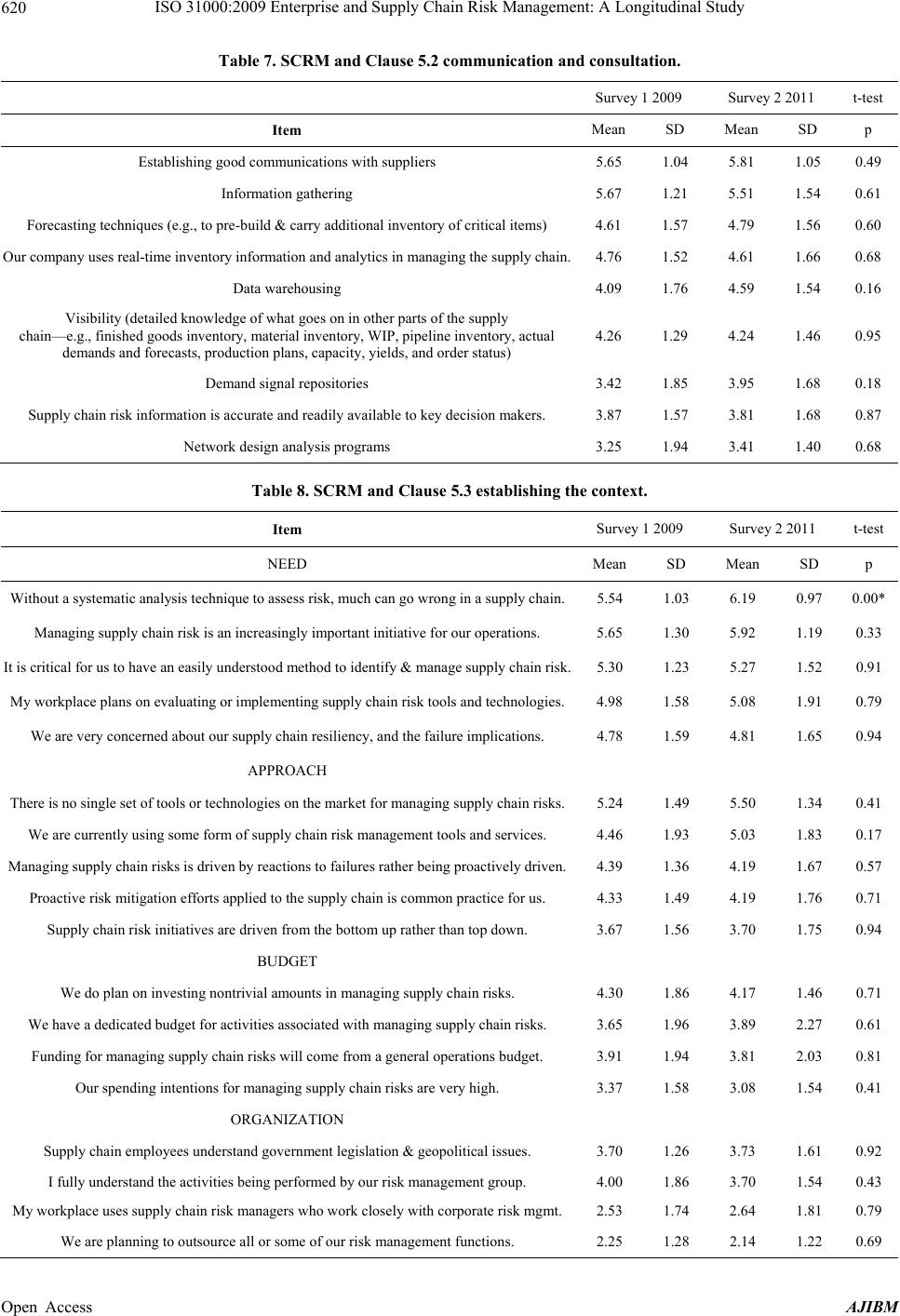

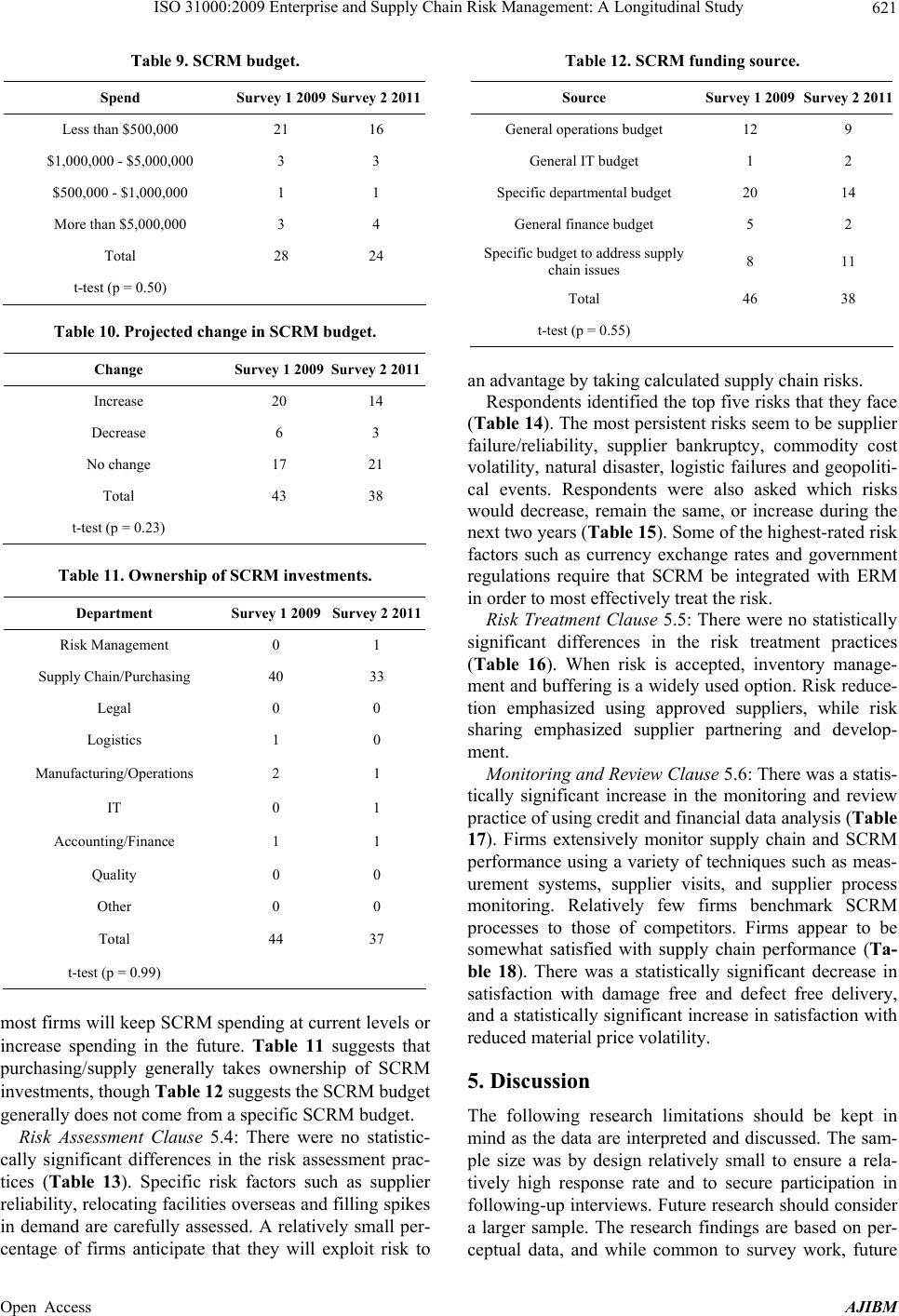

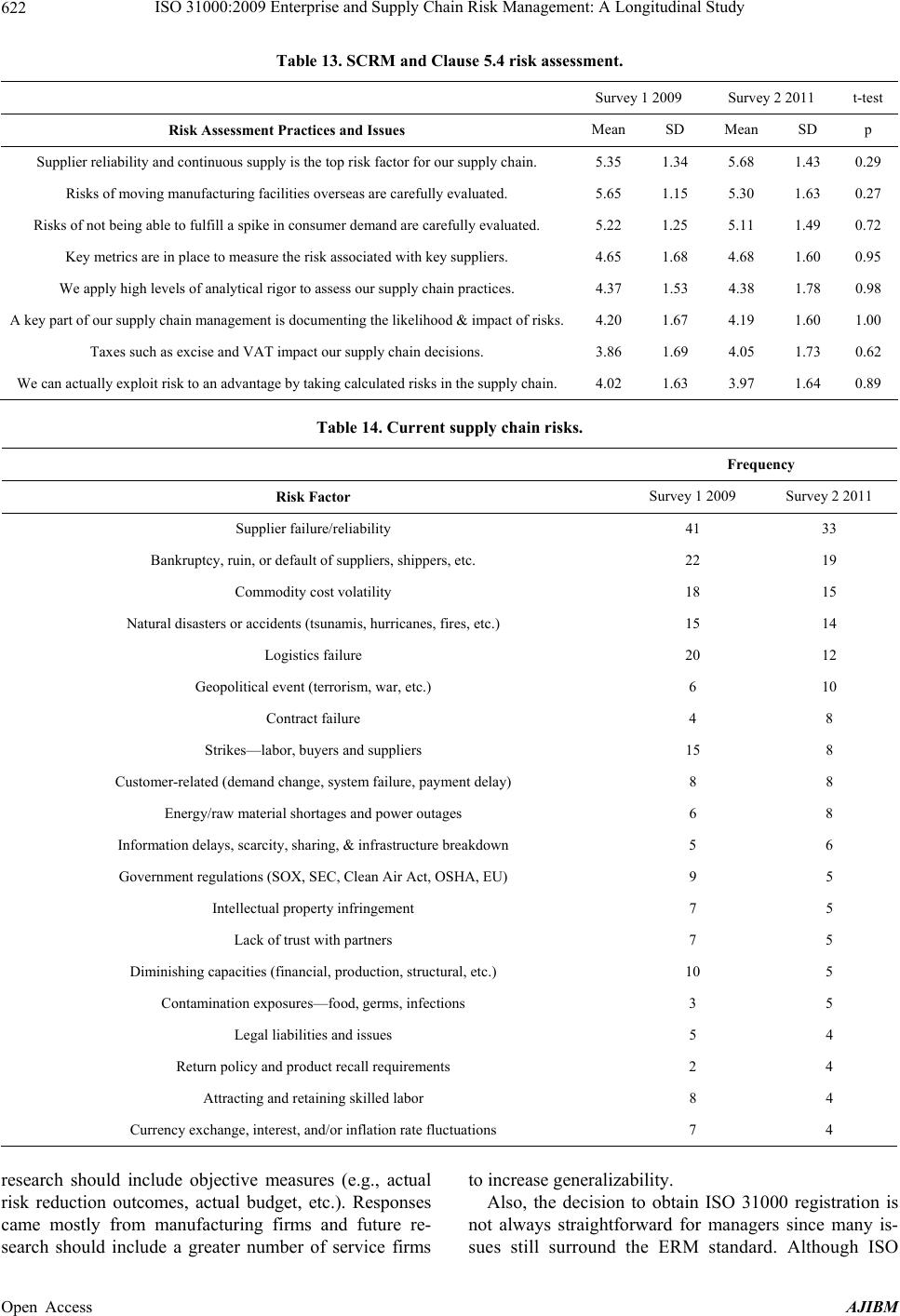

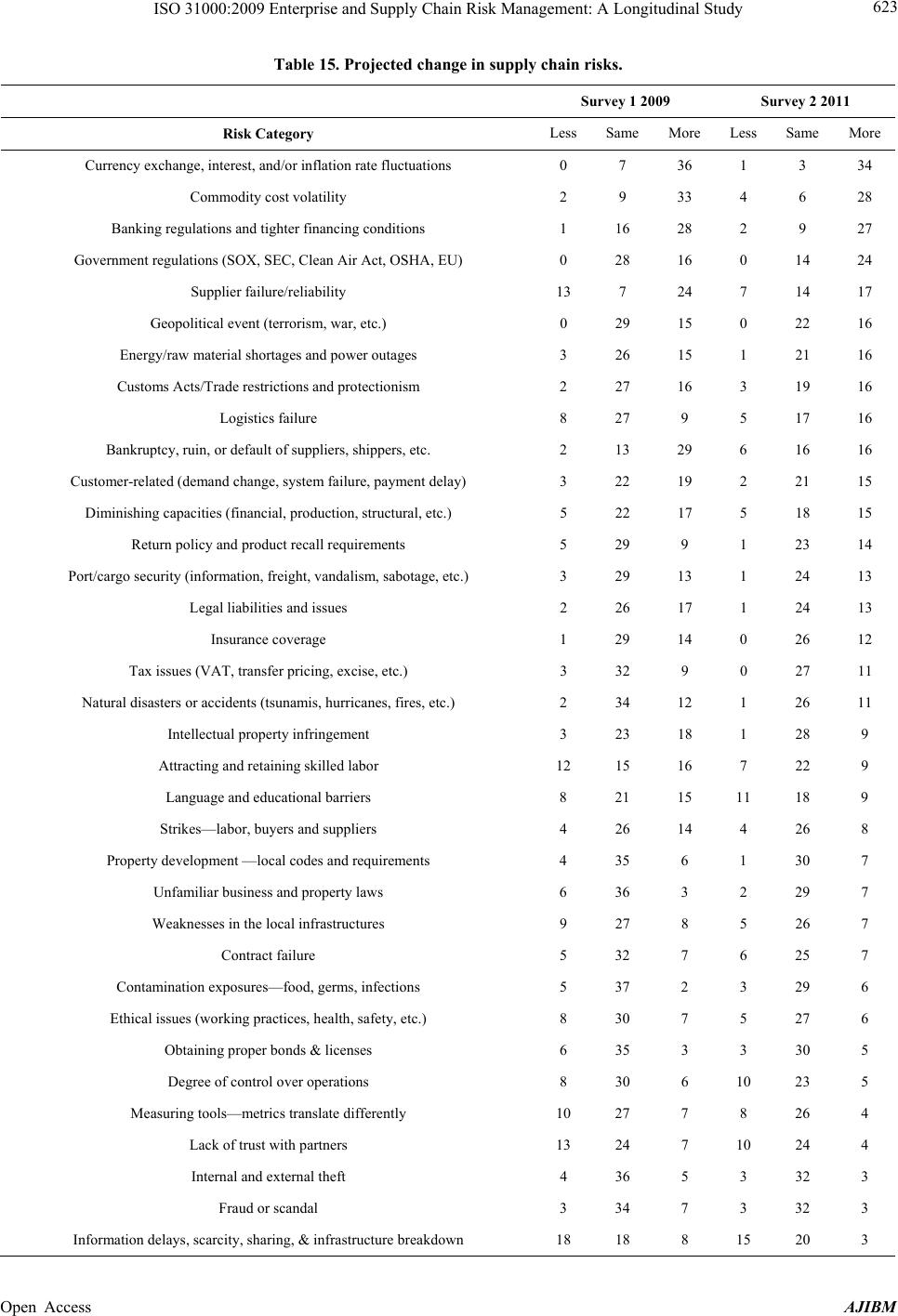

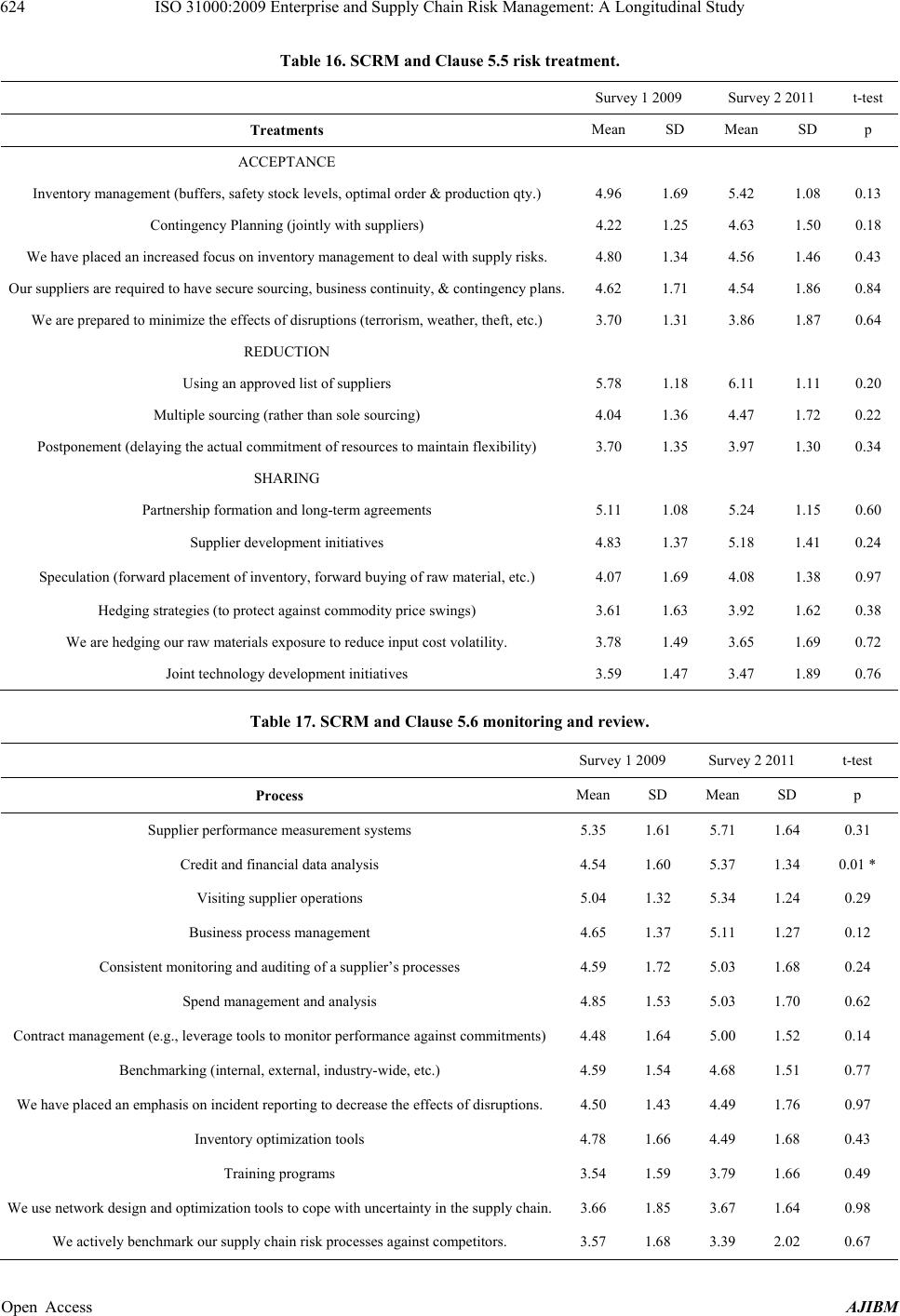

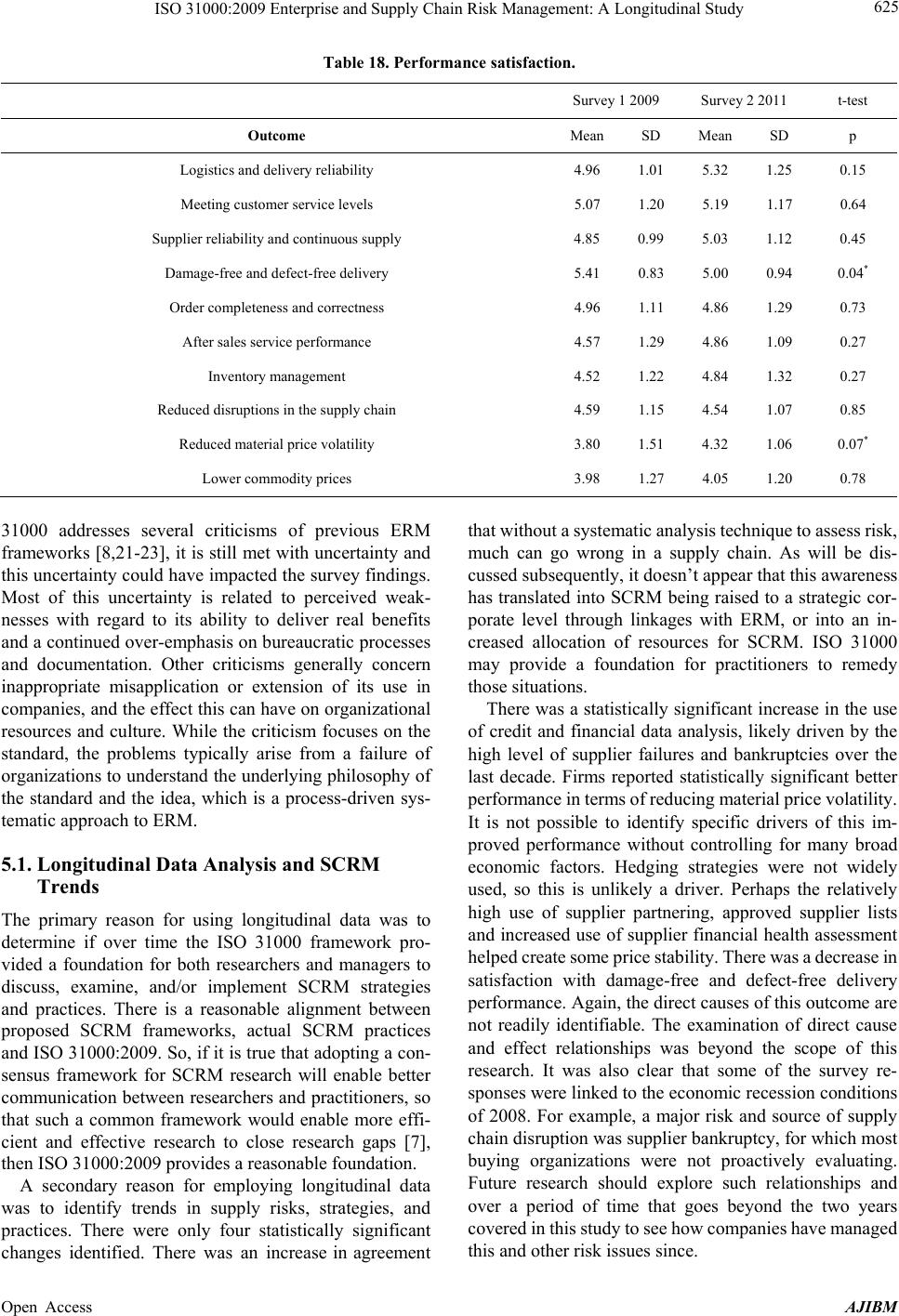

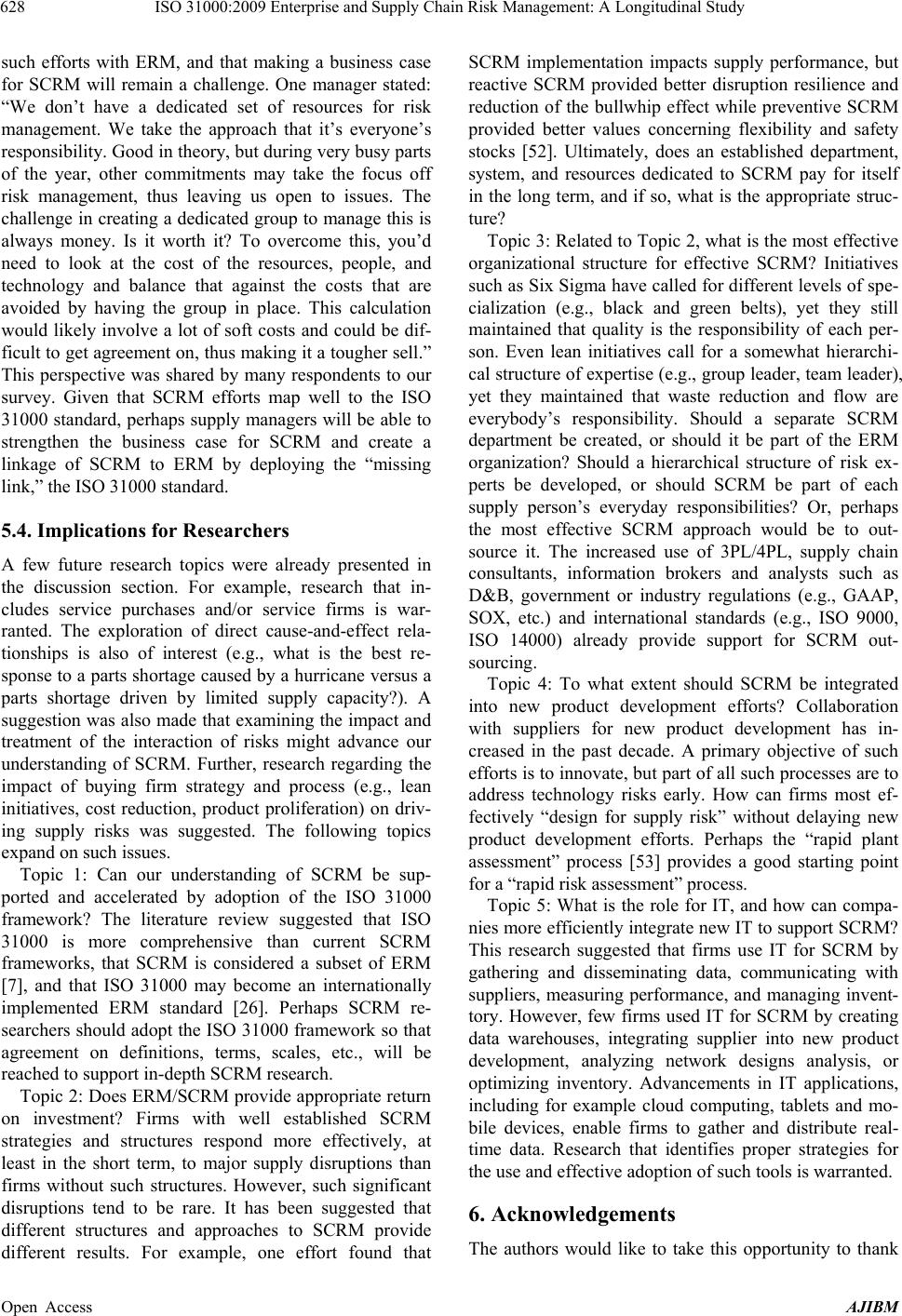

|