Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.11A, 25-31 Published Online November 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.411A005 Open Access 25 Designing Effective CME—Potential Barriers to Practice Change in the Management of Depression: A Qualitative Study Mandana Shirazi1,2, Sagar V. P ar ik h3, Ideh Dadga ran4,5*, Charlotte Silén6 1Education Development Cent e r, Medical Education Department, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, 2Departments of LIM E and Cl ini ca l Science and Education, Söder s juk hu set, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden 3University of Toronto, T oronto, Canada 4Medical-Surgical Nursing Department, Langroud Nursing and Midwifery School, Guilan University of Medical Sciences (GUMS), Rasht, Iran 5Research in Medical Ed u ca t io n , Education Development Center (EDC), Guilan University of Medical Sciences (GUMS), Rasht, Iran 6Center for Medical Educ at io n, Department of Learning, Informatics, Medical Management and Ethics (LIME), Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden Email: mandana.shirazi@ki.se, sagar.parikh@uhn.ca, *i_dadgaran@yahoo.com, charlotte.silen@ki.se Received September 13th, 2013; revised October 16th, 2013; a c c e p te d N o v e mber 14th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Mandana Shirazi et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Aim: The main aim of the current study is to explore GPs’ micro level obstacles of behavior change which affects diagnosis and management of Depressive Disorders following attendance at a Depression CME event. Methods: In this qualitative study, semi-structured interviews exploring GPs’ perceptions and experiences regarding the diagnosis and treatment of depression were done. A purposeful sampling to obtain a broad range of views was carried out among GPs that had participated in an educational interven- tion study three years earlier. Eleven GPs were interviewed and their views were probed in depth to get rich descriptions to ensure trustworthiness of the data. The data were analyzed by using qualitative con- tent analysis. Results: GPs’ beliefs regarding micro level barriers emerged as two important themes indi- vidual and workplace factors. The individual themes included: educational and professional, and the con- textual themes included: psychological disorders and work place categories. The results showed different perceptions on the barriers between the two groups of GPs, those who did change and had a positive per- ception of the CME program they participated in three years ago, and some who did not change. Conclu- sion: The results of this study imply that a number of micro level obstacles were of great importance when managing patients with depression disorders. In order to improve the effectiveness of CME events they should be tailored for the individual and address workplace issues i.e. both individual and contextual factors need attention. Keywords: CME; Depression; Primary Care; Qualitative Study Introduction Quality improvement in health care is a common concept af- fecting all the field professionals. Several factors such as or- ganization, policy and education influence the quality of health- care. Health care quality assurance is a worldwide concern in evaluating the effects of Continuing Medical Education (CME) or Continuing Professional Development (CPD), not only on the physicians’ knowledge and skills, but also on their per- formance and the clinical results (Davis, Thomson, Oxman, & Haynes, 1995; Oxman, Thomson, Davis, & Haynes, 1995). Grol and Weising stated that effective CME interventional events should be planned based on personal, workplace and local health care system needs. They emphasize attention on causal variables that support or hinder targeted health care tai- lored intervention, using appropriate theories in social cognition models and health care results (Grol & Wensing, 2004). The aim of all types of learning is change—changing mental models and creating new ways of thinking, so models of change are relevant. One of the applicable theories (Shirazi et al., 2011) in this field is Readiness to Change model, which underpins the necessity to match interventions with the change stage and corresponding cognitive style. This model, originally known as the “trans-theoretical model”, was developed by James Pro- chaska and Carlo DiClemente in the early 1980s to explain the stages of change observed in persons striving to change addic- tive behaviour (Prochaska, 1992). More specifically, the five stages of change are defined on the basis of people’s propensity to change a specific behaviour and understanding. In the initial stage, individuals are not aware of any problem or contemplat- ing change; in the second stage, they begin contemplating change; in the third stage, they actively prepare, and in the fourth stage, they actually change behaviour. A fifth stage is the *Corresponding author.  M. SHIRAZI ET AL. consolidation or maintenance of the new change. CME in Iran is mandatory for physicians who wish to continue their professional practice (Shirazi et al., 2004). A comprehen- sive project including interventions concerning education on improving General Practitioners’ (GP) knowledge, attitude, and performance in the management of depressive disorders was carried through in 2006 .The evaluation of GPs’ performance was done through the application of unannounced Standardized Patients (SP) (Shirazi et al., 2011). That study showed that some physicians changed their performance while others did not; the reason for lack of change was not identified (Figure 1) (Shirazi et al., 2011). Research in CME interventions has failed to provide reliable and effective methods to change the services and professional performance for the better. In a study from the literature, barri- ers to uptake of Evidence-Based Medicine were explored. That study categorized GPs’ individual practice on the micro level, commercial and consumer organizations on the meso-level (institutions, organizations) and health care policy, media and specific characteristics of evidence on the macro-level (policy level and international scientific community). Existing barriers and possible strategies to overcome these barriers were de- scribed (Hannes et al., 2005). In the current study, we were interested in the barriers to change from the individual physi- cian’s perspective, so we used a qualitative approach for a deeper understanding of the barriers (Pope, Van Royen, & Baker, 2002). According to the literature, there are different obstacles and multifactor barriers behind the GPs’ failure to detect depression. Shortage of time, insufficie nt knowledge, the patients’ failure to reach appropriate mental healthcare services, social and cultural background, and the patients’ resistance to admitting their mood disorders are just some of the underlying factors (Hannes et al., 2005; Shirazi et al., 2013). These obsta- cles may easily be classified into the micro and macro level categories described earlier. The macro level barriers were reported in our previous publication at the micro level (personal and work place) barriers which affect doctors’ performance, ultimately in order to improve the quality of care (Diner et al., 2007). Specifically, we aim to explore GPs’ micro level obsta- cles of behavior change which affect diagnosis and manage- ment of Depressive Disorders following participation in a major CME program for depression. 192 GPs Control Large 19GPs Randomization and doing Pre-assessment Post- assessment Intervention Quantitativestudy 96GPs Intervention 96 GPs Control Control Small Intervention Small (intention) Intervention Large (attitude) 62GPs 17GPs 61GPs 3Mandanashirazi GPs’who chang ed their performance 8GPs 3GPs GPs’who didnot chang e their performance 53GPs 14GPs Semi ‐ structure interv iew 4GPs 2GPs 3GPs 2GPs Qualitativestudy Referen ceNo5 Figure 1. The design of the project including t h e previous and curren t st u di es . Methods This qualitative research was carried out by the use of phe- nomenology method. It consists of the semi-structured inter- views with the data gathering method and qualitative content analysis for data analysis. The interviews were conducted be- tween May 2010 and June 2011 (by MS). Qualitative content analysis is a method that accounts for the contradictory com- ments and unresolved issues concerning the meanings and ap- plication of concepts and procedures. Qualitative content analysis is used in a large number of fields, ranging from marketing and media studies to cultural studies, sociology, and cognitive sci- ence, as well as ot her fields of inquiry (Palmquist, 2010). Participants and Design The participating GPs in this qualitative study originated from a previously published randomized controlled trial (RCT) where interactive teaching and learning methods were used to support GPs in their practice when diagnosing and treating patients with depression disorders (Krippendorff, 2004; Ma- randi, 1996; Shirazi et al., 2011; World Health Organization, 2004). In summary, in that study the participating GPs (n = 192) were randomized into an intervention group (n = 96) or into a control group (n = 96) and assessed at the follow-up (78 and 81 GPs, respectively). At the follow-up the participants in the in- tervention group were categorized as those who had changed their behavior and those who had not. The twelve approached GPs of the present study originated from the intervention group: all five GPs that had not changed their behavior and/or per- formance (i.e. GP, no change) and seven of those who had changed (i.e. GP change) their behavior and/or performance were approached but one of the latter declined to participate. The seven were randomly chosen among all those who had changed and the interviews continued until saturation of the data was reached. The choice of participants was done pur- posely in order to get a wide range of views about the barriers they had met (Krippendorff, 2004) (Figure 1). After signing an informed consentphysicians were asked to agree upon a convenient time and place for the interview. The principal interview questions were as follows: “What do you feel about the barriers of GPs’ behavior change? What is your perception regarding your behavior change following yourpar- ticipation in the CME course three years ago?” The interviewer probed participant responses using questions, such as “Could you say something more about that?”, “What did you think then?”, and “When you mention-what do you mean?” (Kvåle, 2007). The GPs consisted of eight male and three female partici- pants among whom there were three under the age of 40, five between the ages of 40 and 50, and three over 50 years of age. Nine of them had worked as a GP for 10 to 20 years and two of them for over 20 years. As an incentive, each participant re- ceived a CME credit point for his/her participation. Collecting and Analyzing Data The interviews were recorded on a digital voice recorder and subsequently transcribed. All interviews were analyzed. The process of qualitative content analysis often begins during the early stages of data collection. This early involvement in the analysis phase assists in moving back and forth between con- cept development and data collection, and may help direct sub- sequent data collection toward sources that are more useful for Open Access 26  M. SHIRAZI ET AL. addressing the research questions (Zhang, 2012). This process includes open coding, creating categories, and abstraction. Open coding, axial coding, and generating themes were per- formed during data gathering and analysis. Each category was named using content-characteristic words. Subcategories with similar events and incidents were grouped together as catego- ries and categories were grouped as themes. The abstraction process continued as far as it was reasonable and possible (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). Quality Assu rance of Data A nalysis During the analysis of data, certain techniques can help prove our points (Westbrook, 1994). The data reliability of the current study was checked through double-coding and abstracting the data from the same transcripts which was performed by two separate persons. Accuracy Sometimes other sources can be used to confirm inferences from data such as previous successes, contextual experiences, established theories, and representative interpreters. “A content analysis is valid to the extent that its i nferences are upheld in t he face of independently obtained evidence” (Westbrook, 1994). In the present study sampling method was based on the previous contextual findings of another study on “stages of change theory”. The results of the other study were confir med thr o ugh the curre nt study which in turn supports the credibility of data. Results The analysis of data demonstrated barriers of micro level in four categories and two themes. The micro level barrier themes focused on individual and contextual obstacles based on the GPs’ views regarding depression management. The results showed different perceptions on the barriers between the two groups of GPs, those who did change and had a positive per- ception of the CME program they participated in three years ago, and some who did not change. The two themes and four categories are displayed in Table 1. Table 1. Themes, Categories and Subcategories of Micro Level Barriers to Management of Depressive Disorders based on the GPs’ Perspectives. Theme Category Subcategory Physician’s academic training Educational CME Individual factors Professional Motivation Past experience Competence Patients’ attitude and culture Depressive d isorder characteristics Socio-Economic Psychological disorders Colleagues’ Opinion (Interface GPs’ with other professio ns) Practice situation Lack of time MICRO LEVEL BARRIERS Contextual factors (setting factor) Work place issues Financial issues The main themes included: Individual factors (educational and professional categories) and contextual factors (psychological disorders and work place categories). Individual Factors Educational Issues Academic psychiatric training: Potential barriers for diag- nosis and management of depression disorders were based on the GPs’ points of view from two extremes: those who did not change their performance and behavior and those who did. The Psychiatry courses for medical students in Iranare of- fered for no more than a month during their internship which is admittedly insufficient (P3c2). Another participant mentioned inappropriate teaching meth- ods, which were not applicable to doing interviews with pa- tients during their general undergraduate courses in medicine. “It seems that one of the hindering problems regarding the- detection and treatment of depression is that we are not well trained with any proper clinical interview techniques in the general medical courses” (P4C45). CME Normally the CME program is not designed based on GPs’ needs. A participant explained: “I remember a meeting was held by a group of surgeons about different ways of operating breast cancer. What are the advantages of knowing different methods of operating breast cancer for a general practitioner (GP)? If the meeting was about different ways of diagnosis and screening of breast can- cer, it would help us diagnose the disease. I only attended the meeting to gain extra CME credit points. We neither under- stood what the surgeons said nor did they care whether we understood their points or not. The subject is of no use to us in general” (P8c13). One of the GPs’ who did not change his performance and behavior stated: “In a regular CME program, the sessions were mere lect ures and were thus uninteresting to us. They do not affect our knowledge and performance as the content will be forgotten very soon” (P4c6). “CME courses regarding one subject normally continue in an excessively big interval which in turn leads to the loss of information” (P10c6). Specific CME Program: “The specific CME course in- creased my knowledge and changed my view. After the course, the quality of my diagnosis and treatment improved. For in- stance, prior to the course I didn’t care and ask if the patients were suicidal because I thought they would not like to talk about it. But now I follow through with that point with no ex- ception and then I try to pay attention to whether or not they are seriously considering suicide” (P3c1)? “What we read in books did not even begin to compare with the information provided by teachers in specific CME events. The provided information was more practical and gave us more useful information for our practice. Especially in the CME course when i had interviewed with Standardized Patients and get feedback from teachers I had learnt a lot” (P8). “Following my participation in the course, my motivation for self-study increased due to the useful printed materials and references that the course instructors provided regarding the management of depression” (P1C5). Open Access 27  M. SHIRAZI ET AL. “Even though I had previously counseled depressed patients and diagnosed and treated them; after attending the CME event I am more capable of distinguishing between different types of depression and combining disorders” (P11, C11, C13). “Following my participation in the course, I have followed up with severely depressed patients who may have committed suicide or are prone to do so and referred them to a psychia- trist” (P11C12) (P8C1). “After participating in the course I began to prescribe drugs more carefully. Before our attendance in a specific course, when a patient complained about her/his difficulty to sleep at night, without asking him further questions in order to rule out depression, I would prescribe sleeping pills for him, instead of prescribing Fluoxetine or another antidepressant” (P3c19). Some of GPs’ who did not change their performance and behavior made the following statements: “I think the previous CME course (specific course) in which I participated, had no effect on my performance as there are several more important disorders than depression” (P7C1). “I do not remember crucial points of the specific CME course that you are asking of it. I just remember that Depres- sion is an important disorder and we should pay more attention to it but I have participated in that course simply to gain CME credits” (P4C36, P4C37). “The mentioned course had no significant effect on my per- formance. I mean, I refer depressed patients to the psychiatrist who works in our hospital” (P4C38)? Contextual Fa ct ors Work Place Issues The results of this study also indicated that work place and conditions can affect the GPs’ professional requirements re- garding management of Depressive Disorders’. Some GPs’ who did change their performance and behavior stated the following: “I work in my private office and the number of depressed pa- tients who consult with me has increased following my partici- pation in the course. I may have missed some c ases prior to the course” (P6C30). One of the GPs’ who did not change his performance and behavior said: “Since we have a very crowded and terrible emergency ward in the hospital…, we don’t have enough time to assess the pa- tients’ health and to talk and consult with them to diagnose DD” (P4C4). “I closed my private clinic eight months after participating in that course so the value of what has been taught to me was reduced due to the fact that I was working in the emergency ward. In that place there is no time for treating depressed pa- tients” (P4C40). Shortage of Time Among other problems regarding workplace is the shortage of time for consulting with depressed patients. In this regard, a physician who did change his practice and behavior claimed: “In my office normally I spent 25 - 30 minutes on consulta- tion with a depressed patient and I remember a case in which after a 30 minute discussion, the patient refused to accept his depressive disorder. Other patients sitting in waiting room complained to my secretary saying that I am a talkative doctor. This happened to me several times and other patients became angry with me and complained to me when they entered my office” (P318). Even though interviewing depressed patients is a time con- suming process, most of the patients will accept my diagnosis and are satisfied with it so they suggest my services to their relatives (PC20). Another participant who did not change his method of prac- tice mentioned: “For instance, since I am working in a very crowded emer- gency ward, other patients have to wait there for a long time which is not possible for me to provide them with the proper services. If I had more than 10 minutes to talk to each patient, I would be able to diagnose whether the patient is depressed or not” (P4C47). Other factors such as GPs’ motivation, past experience and their competencies have been labeled as an individual theme. Discussion The main research questions “why did some of the physicians following their participation in tailored CME intervention change their performance and others’ did not”? and “How to explore GPs’ obstacles of behavior change which effects their diagnosis and management of Depressive Disorders?” These are the main concerns of the current study which remain unan- swered in almost all parts of the world (Jewell, 2003). Based on the present research findings, several factors affect GPs’ behavior change such as individual factors and setting specifications. Underpinning the andragogia view such as “Bandura”, adult learning theory depends on three important factors: personal, contextual, and behavioral factors. So our findings are in line with Bandura and stages of change theories which emphasized on individual motivation to change their behavior (Rimer & Glanz, 2005). We have found that behavior change occurs, when the personal and contextual factors are considered based on the GPs’ points of view. We interprets and show pictures of GPs’ barriers of behavior change into the context of the theoretical back ground of CME which is the base of the recent study (Figure 2). Individual Factors Education Academic Training: The preliminary task of medical schools through a well-designed curriculum is to train medical students in order to gain adequate knowledge, skills and attitudes and graduate them as competent physicians who can guarantee the patient safety (Pellegrino, 2002). But the current case is re- garding some incompetent graduate GPs’ in the field of Psy- chiatry due to their shortage of Psychiatry course during their undergraduate study (P3 and P4) (Lecrubier, 2007; Mitchell, Vaze, & Rao, 2009; Wilhelm, Brownhill, Harris, & Harris, 2006). It could be reflecting the educational organizational difficulties such as the medical school psychiatry curriculum: Syllabus, teaching and evaluation methods, educational envi- ronment etc. Based on the findings of the study at hand, GPs’ believed that their academic psychiatry courses and their knowledge and skill especially in the field of management of depressive disorders were insufficient. They claimed that their clinical psychiatry education period was too short P3 P4. In line with our results Wilson directed a study regarding what GPs’ essential needs are regarding the management of psychiatry Open Access 28  M. SHIRAZI ET AL. Open Access 29 Education GPs' as a Profession Psych ologica l Disorder W ork place Figure 2. Micro level Barriers of GPs’ behavior change. disorders based on their view points and which knowledge, skills and attitudes should be included in the current medical curriculum in the University of Aberdeen. They have found that depression is the most common psychiatry disorder for the management of which they would like to gain competence. In contrast with our findings, GPs’ in their study stated that their needs for management of depression is in the domain of knowledge but the result of our study expressed GPs’ needs in the skill and attitude domains (Wilson, Eagles, Platt, & McKenzie, 2007). Nisha Dogra et al. stated that psychiatry curriculum development for medical students is a complex process due to the fact that successful implementation should be kept in their curriculum developers’ mind (Dogra et al., 2010). Overall at present time in Iran at TUMS medical cur- riculum is reforming but there is still a necessity to include current study results to the curriculum. In some countries such as Iran, when a difficulty regarding physicians’ competency for management of disease happens, CME would be responsible to overcome the current barriers. CME Training General issue and Specific issues of CME: Based on our data the GPs’ had two perspectives; the first, focused on their general idea regarding the CME events and the second was related to their specific views of tailored CME courses in which they had participated. Their general idea of CME events in both groups demonstrated that they were not satisfied with regular CME events for several reasons such as: impractical topics which did not address the GPS’ main issues, and applying di- dactic educational methods, etc (P8, P4, P10). Their opinion of the specifically tailored CME (Shirazi et al., 2011) was totally different. Some of GPs who had changed their performance, in contrast with the other group, found it practical, interactive, and more relevant to their real needs based on the data which was extracted from interviewing the two groups of GPs’ (P1, P3, P8, P11). In accordance with our findings, applying interactive meth- ods, Marinopolos et al. directed a systematic review for assess- ing the physicians’ behavior change and improving their clini- cal outcomes through participation in a CME Intervention. They suggested that it has been successful, at least to some extent, in not only attaining, but also in sustaining the intended objectives. They illustrated shared factors throughout the stud- ies. For instance, using printed materials was proven to be less effective than using live media and multi-media. Applying multifaceted teaching and learning methods was more effective than applying a single method. Hence the staff considered these factors in planning CME events to enhance its effectiveness (Marinopoulos et al., 2007). Another systematic review focused on “assessing barriers to physicians’ adherence to practice guidelines”. They found seven general categories of barriers such as: knowledge, attitudes, behavior, awareness, familiarity, agreement, and lack of self-efficacy. Thus our general finding regarding participants’ dissatisfaction in Iranian CME events are due to the use of didactic methods and do not consider the main attributes of an effective CME program by CME provid- ers. Those programs should be modified and adopted to the specific design, based on GPs’ needs and applying a theoretical framework and utilizing multifaceted methods, the same as our previous studies which satisfied most attendees (Shirazi et al., 2011, 2007, 2009, 2008). Modeling CME Intervention Interestingly, those GPs’ who had changed their performance and stages of change were in intervention groups and few of them who had not changed assumed that the CME course they participated in was not sufficient for them which could be in- terpreted as their inadequate motivation for learning about de- pression management (P4). Their lack of motivation could be related to their work place since most of them were working in the emergency wards of the hospital and they did not feel that their needs were aligned with depressive disorders. In contrast, other GPs working in a primary health care setting suggested the usefulness of the previous course and its content sustain- ability of course content (for example some of them remember some specific educational sessions after three years, which they  M. SHIRAZI ET AL. had interviewed with Standardized Patients) (SP) (P8). In line with our findings, in a review article, a writer quoted “Continuous Medical Education (CME) generally has failed to address the physicians’ educational needs”. They have empha- sized that if CME providers wish to improve doctors learning translating knowledge into physicians’ practice, there is a cru- cial need to understand theories of physician behavior change and characteristics of effective CME interventions. The writers have then discussed the necessity of person center education in which physicians preferred independence and self-directed learning. So if these issues are overlooked, then the CME pro- gram is doomed to fail (Amin, 2000). Following CME pro- gram’s exploring the barriers of behavior change based on the participants’ view, there is also a very important component which can help us overcome the obstacles and there for design more effective CME courses in the future. It is thus highly recommended to design CME programs based on accepted theories of behavior change. Based on theoretical perspectives of “stages of change” those GPs who did not change their performance, also remained in the attitude stage after participation in CME specific courses. Data analysis showed that those GPs’ views supported “stages of change” theory, where they had participated three years ago. GPs’ who were in the attitude stage and did not change their performance did not feel they need to change their performance in the field of management of depression (P4). Based on the data they did not feel they need to participate in management depression disorder course. So, they participated in it merely to gain CME credit points. Thus CME providers and policy mak- ers should consider these issues in designing future CME pro- grams. They should assess GPs’ readiness to change before they participate in the courses. If participants are not ready then participating in the course is useless for them (Shirazi et al., 2011, 2007, 2009, 2008). Work place and Practice Setting: In current study the physi- cians’ work place played an important role. For instance, some physicians who worked in primary health care settings stated that a tailored CME course (participated three year ago) was efficient in their performance (P11). However, for some others who were working in the emergency wards from another ex- treme the program was not useful (P4). According to one pub- lished study work place could affect the doctors’ perceived needs for the management a depression; they have found that those doctors who work in a hospital had different psychiatric needs in comparison with those who work in the primary care (Wilson et al., 2007). Setting and workplace could be acted as a potential barriers for GPs’ behavior change. Interestingly the basement data from previous study demonstrated that GPs’ work place had direct effects on their professional needs and also on their readiness to change and learn more about specific courses (P11, P4). Shortage of time: Inadequate time is an issue that was raised by both groups of GPs’ from two extremes regarding barriers of behavior change. But their explanation of this process was var- ied. The ones who had changed their performance believed that due to an increased patient satisfaction the total number of their patients will increase (P3). In contrast, others who worked in the crowded work places such as emergency wards, need to spend more time to explore depression which they thoughts it impossible (P4). As confirmed in our study, time shortage is commonly de- scribed as a barrier to adherence by more than 10% of GPs’ who participated on their study (3). Other researchers found the same issue which has been arisen as barrier, due to the nature of the depression disorder, for eliciting the symptoms from pa- tients there is a need to dedicate more time than other disorders and it will be increased socio-economic deficit of physician (Chew-Graham, Mullin, May, Hedley, & Cole, 2002; Pierce & Gunn, 2007). Strengths and limitations of this study: This study has some limitations. Firstly, to transfer the results to other countries, the context of the Iranian healthcare system has to be taken into account. Secondly, the rather small number of participants can be seen as a limitation. The interviews were carried out until no new information was added, which can be seen as a strength, even if it is probable that the reason for reaching saturation with a rather small number of participants might be related to the fact that they were recruited from the RCT of a previous study. On the other hand, since the participants had been part of an educational intervention with a follow-up, they were engaged and their characteristics were known which guaranteed a broad view of the issues in focus. Thirdly, all participating GPs had more than 10 years’ of experience, which could be seen as a limitation even though GPs with more experience might have a deeper understanding of the questions probed in this study. One of the strengths in this study was that all authors were engaged in the analysis and their different experiences made it possible to challenge each other’s assumptions and constantly return to the data for confirmation of interpretations. An additional strength of the current study was the use of sampling method based on the previous contextual findings of previous studies according to the “stages of change theory”. The previous results were confirmed through the current study which appears to approve the credibility of the data. Conclusion To make complex changes in the physicians’ performance, we need to overcome potential barriers at various levels (Grol & Wensing, 2004). Common CME programs do not have sci- entific design based on the behavior change theory and also they do not explore participants’ perceptions and performance following attending in those activities. In order to make them more effective, there is a need to deepen the understanding of GPs’ experience regarding the obstacles of behavior change. Otherwise, CME providers could not be able to estimate the potential barriers of behavior change. CME organizers should take it into account that the nature of individual and contextual factors (Micro level)—Educational, professional, Psychological disorders and Work place issues—to design a successful CME intervention and utilize underpinning and testable theories such as the “stages of change”. REFERENCES Amin, Z. (2000). Theory and practice in continuing medical education. Annals of the Academy of Medic ine, Sin gapore, 29, 498-502. Chew-Graham, C. A., Mullin, S., May, C. R., Hedley, S., & Cole, H. (2002). Managing depression in primary care: Another example of the inverse care law? Family Practice, 19, 632-637. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/fampra/19.6.632 Davis, D. A., Thomson, M. A., Oxman, A. D., & Haynes, R. B. (1995). Changing physician performance. JAMA: The Journal of the Ameri- can Medical Association, 274, 700-705. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.1995.03530090032018 Open Access 30  M. SHIRAZI ET AL. Open Access 31 Diner, B. M., Carpenter, C. R., O’Connell, T., Pang, P., Brown, M. D., Seupaul, R. A., Mayer, D., et al. (2007). Graduate medical education and knowledge translation: Role models, information pipelines, and practice change thresholds. Academic Emergency Medicine, 14, 1008- 1014. Dogra, N., Höschl, C., Moussaoui, D., Gask, L., Coskun, B., & Baron, D. (2010). Developing a medical student curriculum in psychiatry. In L. Gask, B. Coskun, & D. A. Baron (Eds.), Teaching Psychiatry: Putting Theory into Practice (pp. 27-46), Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of advanced nursing, 62, 107-115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x Grol, R., & Wensing, M. (2004). What drives change? Barriers to and incentives for achieving evidence-based practice. The Medical Jour- nal of Australia, 180, S57. Hannes, K., Leys, M., Vermeire, E., Aertgeerts, B., Buntinx, F., & Depoorter, A.-M. (2005). Implementing evidence-based medicine in general practice: A focus group based study. BMC Family Practice, 6, 37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-6-37 Jewell, D. (2003). How to change clinical behaviour: No answers yet. The British Journal of General Practice, 53, 266. Krippendorff, K. (2004). Book review: Content analysis: An introduc- tion to its methodology (2nd ed.). Organizational Research Methods, 13, 392-394. Kvåle, K. (2007). Do cancer patients always want to talk about difficult emotions? A qualitative study of cancer inpatients communication needs. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 11, 320-327. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2007.01.002 Lecrubier, Y. (2007). Widespread underrecognition and undertreatment of anxiety and mood disorders: Results from 3 European studies. The Journal of Clinical Psychia t ry , 68, 36-41. Marandi, A. (1996). Integrating medical education and health services: The Iranian experience. Med Educ, 30, 4-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.1996.tb00709.x Marinopoulos, S. S., Dorman, T., Ratanawongsa, N., Wilson, L. M., Ashar, B. H., Magaziner, J. L., Qayyum, R., et al. (2007). Effective- ness of continuing medical education. Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments, 149, 1-69. Mitchell, A. J., Vaze, A., & Rao, S. (2009). Clinical diagnosis of de- pression in primary care: A meta-analysis. The Lancet, 374, 609-619. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60879-5 Oxman, A. D., Thomson, M. A., Davis, D. A., & Haynes, R. B. (1995). No magic bullets: A systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Associa- tion Journal, 153, 1423. Palmquist, M. (2010). Writing guide: Content analysis. Fort Collins, CO: Colorado State University. Pellegrino, E. D. (2002). Professionalism, profession and the virtues of the good physician. Mount Sinai Jo urnal of Medicine, 69, 378-384. Pierce, D., & Gunn, J. (2007). GPs’ use of problem solving therapy for depression: A qualitative study of barriers to and enablers of evi- dence based care. BMC Family Practice, 8, 24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-8-24 Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C., & Norcross, J. C. (1992). In search of how people change. Applications to Addictive Behaviours, 47, 1102-1114. Pope, C., Van Royen, P., & Baker, R. (2002). Qualitative methods in research on healthcare quality. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 11, 148-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/qhc.11.2.148 Rimer, B. K., & Glanz, K. (2005). Theory at a glance: A guide for health promotion practice. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Shirazi, M., Gandomkar, R., Ponzer, S., & Silén, C. (2013). Exploring the macro level barriers that affect Iranian GPs’ diagnosis and man- agement of depression disorders. European Journal for Person Cen- tered Healthcare, 1. (in Press) www.bjll.org/index.php/ejpch Shirazi, M., Lonka, K., Parikh, S. V., Ristner, G., Alaeddini, F., Sadeghi, M., & Wahlstrom, R. (2011). A tailored educational inter- vention improves doctor’s performance in managing depression: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Prac- tice, 19, 16-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01761.x Shirazi, M., Assadi, S. M., Sadeghi, M., Zeinalo o, A. A., Kashani, A. S., Arbabi, M., Wahlstrom, R., et al. (2007). Applying a modified Pro- chaska’s model of readiness to change for general practitioners on depressive disorders in CME programmes: Validation of tool. Jour- nal of Evaluation in Clinical Pract ice, 13, 298-302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00735.x Shirazi, M., Parikh, S. V., Alaeddini, F., Lonka, K., Zeinaloo, A. A., Sadeghi, M., Wahlstrom, R., et al. (2009). Effects on knowledge and attitudes of using stages of change to train general practitioners on management of depression: A randomized controlled study. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 54, 693-700. Shirazi, M., Sadegh i, M., E mami, A., Kashan i, A. S., Pa rikh, S., Alaed- dini, F., Wahlstrom, R., et al. (2011). Training and validation of stan- dardized patients for unannounced assessment of physicians’ man- agement of depression. Academic Psychiatry, 35, 382-387. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.35.6.382 Shirazi, M., Zeinaloo, A., Parikh, S., Sadeghi, M., Taghva, A., Arbabi, M., Wahlstrom, R., et al. (2008). Effects on readiness to change of an educational intervention on depressive disorders for general physi- cians in primary care based on a modified Prochaska model—A ran- domized controlled study. Family Practice, 25, 98-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmn008 Shirazi, M., Zeinaloo, A., Sabouri, K., & Alaedini, F. (2004). Assessing the gap between current and desirable needs in TUMS CME Unit: Participants viewpoints. Iranian Journal of Medical Education, 5, 17-22. Westbrook, L. (1994). Qualitative research methods: A review of major stages, data analysis techniques, and quality controls. Library & In- formation Science Research, 1 6 , 241-254. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0740-8188(94)90026-4 Wilhelm, K., Brownhill, S., Harris, J., & Harris, P. (2006). Depres- sion—What should the doctor ask? Australian Family Physician, 35, 163-165. Wilson, S., Eagles, J. M., Platt, J. E., & McKenzie, H. (2007). Core undergraduate psychiatry: What do non-specialists need to know? Medical Education, 41, 698-702. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02790.x World Health Organization (2004). Prevention of mental disorders: Effective interventions and policy options: Summary report. Geneva: World Health Organization Zhang, Y. (2012). College students’ uses and perceptions of social networking sites for health and wellness informatio n. http://informationr.net/ir/17-3/paper523.html

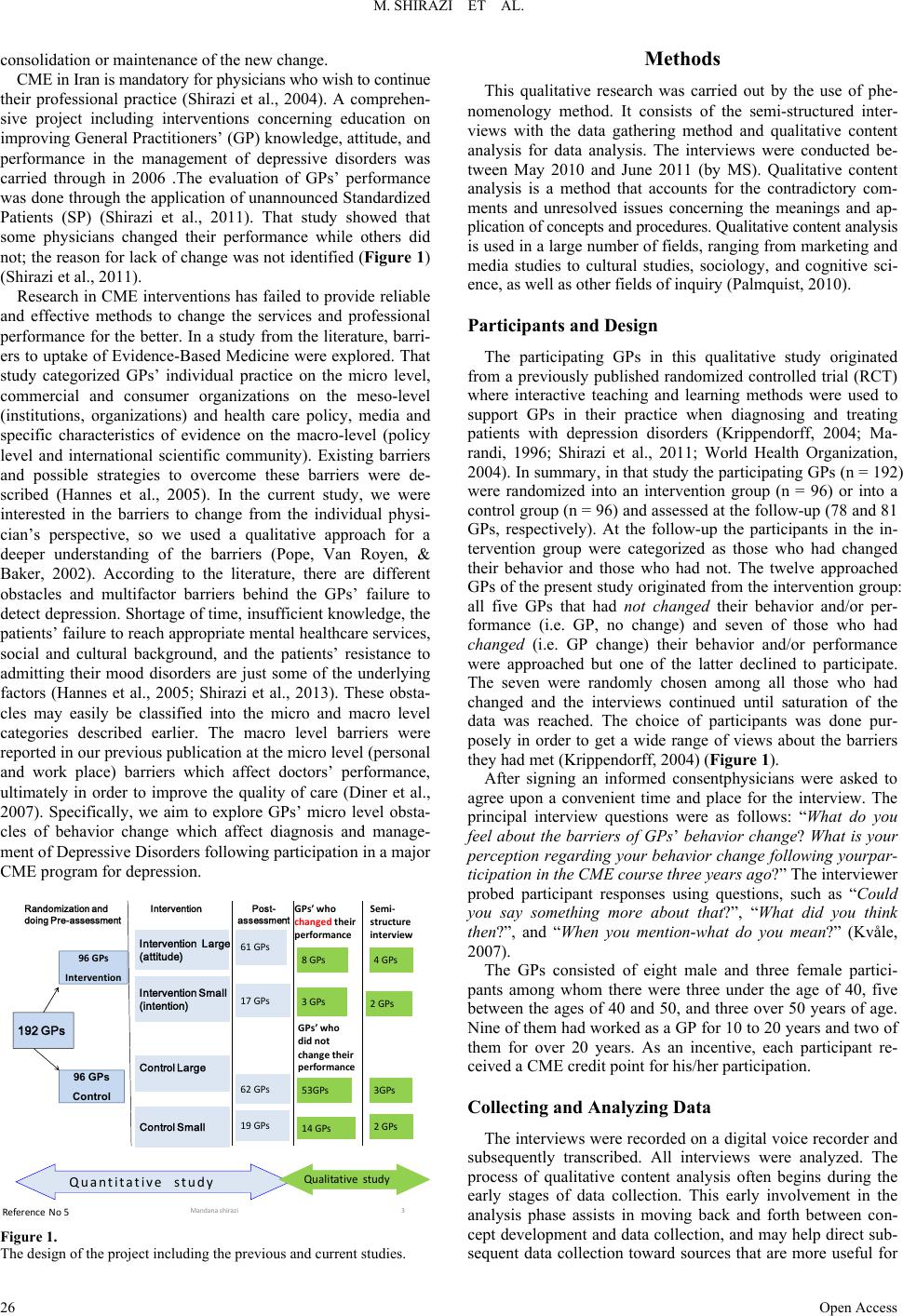

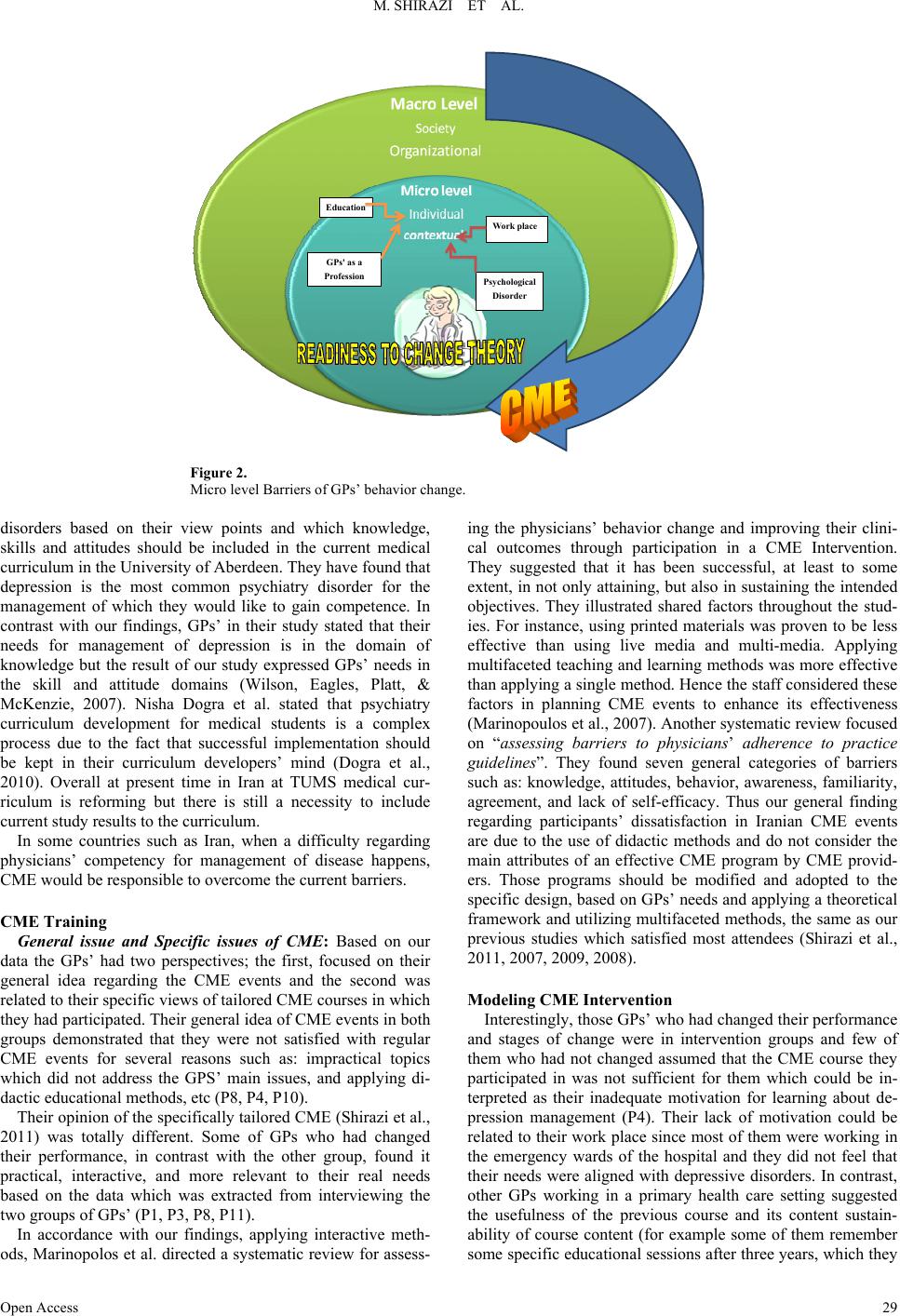

|