Journal of Service Science and Management

Vol.10 No.04(2017), Article ID:78475,6 pages

10.4236/jssm.2017.104031

Study on the Spillover Effects of Overseas Brand Crises

Qing Li, Zheng Jiang

Shenzhen Tourism College, Jinan University, Shenzhen, China

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: July 10, 2017; Accepted: August 13, 2017; Published: August 16, 2017

ABSTRACT

Innocent domestic brands are always infected by some overseas brand crises. In this article, we examined the factors that can inhibit the spillover effects of overseas brand crises. The results revealed that high level of mental construal and national identity can help domestic brands defend the negative spillover effects of overseas brand crises. For consumers with low level of national identity, they evaluate domestic brands more favorably when they are at the high level of construal than assigned at the low level of construal.

Keywords:

Overseas Brand Crises, Spillover Effects, Domestic Brands, National Identity, Construal Level

1. Introduction

Previous researches find that while consumers’ social identities are threatened, they will choose to defend it or abandon it [1] [2] . Consumers are divided into in-groups and out-groups according to the country they come from under the conditions of some overseas brand crises. Once they choose to abandon the identity threatened, the spillover effects of overseas brand crises are emerging, that is, innocent domestic brands are negatively affected by the overseas brand crises. Especially when consumers’ in-group identification is low, consumers will lay the blame for overseas brand crises on the domestic background, and then evaluate the domestic brands negatively. We wonder whether these spillover effects can be reduced or eliminated. What are the boundary conditions that can weaken the spillover effects of the overseas brand crises?

In this article, we propose that some overseas brand crises are due to the factors related to the domestic because consumers pay more attentions to the environmental background of a crisis than to the brands in a certain crisis. When consumers are in low construal level, they will pay more attention to the external factors than to the internal factors [3] . Therefore, we propose that construal levels will play important roles in inhibiting the spillover effects of overseas brand crises.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Construal Level Theory

According to the temporal construal theory, distant future situations are construed on a higher level (i.e., using more abstract and central features) than near future situation [3] . Extending on this, researches on construal level theory suggest that a high versus low level of mental construal prompts people to think more abstractly [4] [5] . Specifically, they are likely to represent events in terms of general, superordinate, and decontextualized features rather than in terms of specific, subordinate, and contextualized features.

2.2. The Interaction Effects of Construal Level and National Identity

Prior researches on construal level theory proposed that a high level of mental construal motivates people to blame the features or characteristics of personality for something happened, while a low level of mental construal actuates people to blame the background or situations that things happened. According to these, consumers with high level of mental construal will blame the overseas brand for an overseas brand crisis. However, consumers with low level of mental construal will blame China background for an overseas brand crisis. Kyung et al. [6] also found that consumers faced with distant future situations are more likely to blame the Protagonist of an event. Körner and Volk proposed that consumers made more deontological judgments under concrete (vs. abstract) construal [7] . From the aboves, consumers will evaluate an overseas crisis more fairly and impartially under concrete (vs. abstract) construal. Therefore, consumers with high (vs. low) level of mental construal evaluate domestic brand more positively under the context of an overseas brand crisis.

According to social identity theory, when group status is threatened, highly committed group members respond with greater in-group favoritism [1] [8] . Petriglieri [2] proposed that there are two kinds of identity threat coping responses: identity-protection responses and identity restructuring responses. The former means to protect the threatened identity, and the latter to make it less of an object for potential harm. Similarity, White and Argo [9] find that when consumers experience a threat to aspect of their social identity (e.g., receive negative information regarding their national group), they sometimes avoid products associated with that identity and sometimes increase preference for identity-linked products. In conclusion, when consumers are highly identified with their country, they will defend the domestic brand under the context of an overseas brand crisis. However, consumers low in national identity will resist the identity-related brands or products under the context of an overseas brand crisis. In combine with the literatures on construal level theory above, we propose that national identity will moderates the effects of construal level on domestic brand evaluations. Hypotheses are as follows:

H1: To consumers with low national identity, they evaluate domestic brands more positively at higher (vs. lower) levels of construal under the context of overseas brand crises.

H2: The effects of construal levels on consumers’ evaluations of domestic brands will be attenuated for those with high national identity.

3. Research Design

3.1. Method

To examine H1 and H2, A 2 (construal level: high vs. low) × 2 (national identity: high vs. low) between-subjects experimental design was used. 60 undergraduate students (70% females, Mage = 18.7) from a business course at a large university in Southern China participated in exchange for course credit.

Firstly, participants were told that the survey was about university students’ mental health, and it includes three unrelated parts. The first part was to prime construal levels and measure participants’ national identities. According to Freitas et al. [10] , participants assigned to a high level of mental construal were directed to consider why they would engage in a health improvement activity, whereas participants assigned to a low level of mental construal were directed to consider how they would engage in the same activity. Then participants completed a six-item scale which measures national identities [11] (α = 0.819), all using 7-pointscales ranging from1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), This included items such as “When someone criticizes my country, it feels like a personal insult”, “When I talk about this country, I usually say ‘we’ rather than ‘they’”, “I am very interested in what others think about my country”.

The second part was a piece of real news about an overseas brand, named Johnson & Johnson which suffered from a crisis. In the overseas brand crisis condition, participants read a news report stating that while recalling defective products, the overseas brand, named Johnson & Johnson, excluded the Chinese market.

The third part was to rate the desirability of domestic brands stereotypes on a seven-point scales, including competence and morality dimensions. The measure consisted of seven stereotype attributes [12] (α = 0.769).three were assumed to refer to the moral realm (i.e. tolerant, modest) and four to the realm of competence (i.e. efficient, competitive). Participants were then asked to choose which T-shirts they preferred among three different ones. One is related to the in-groups, another to the out-groups and the third one is neutral.

3.2. Results

According to Lee and Robbins [13] , the mean was used as a cutoff. Participants were then selected as a high-level national identity group member if they scored below the mean, and selected as a low-level group member if they scored the mean or higher.

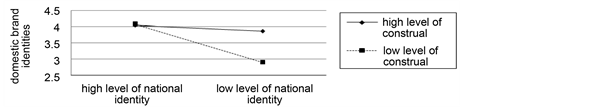

According to the ANOVA analysis, the main effect of national identity was significant, F(1, 56) = 10.23, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.154, participants with high national identity rated the domestic brand identities more favorably (M = 4.06, SD = 0.141) than participants with low national identity (M = 3.38, SD = 0.158). As predicted, the interaction of national identity and construal level on national brand identity desirability ratings was significant (F(1, 56) = 5.63, p < 0.04, η2 = 0.09) (see Figure 1). Planned contrasts revealed that participants with low level of national identity evaluate the domestic brand identities more positively when they are assigned to the high level of construal (M = 3.86, SD = 0.588) than when assigned to the low level of construal (M = 2.89, SD = 0.97), F(1, 25) = 10.53, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.296). Thus, H1 was supported. However, when with high level of national identity, participants assigned to the high level of construal (M = 4.04, SD = 0.91) and to the low level of construal (M = 4.07, SD = 0.76) perceived the same identities of the domestic brands, F(1, 31) = 0.013, p > 0.1. Thus, H2 was supported.

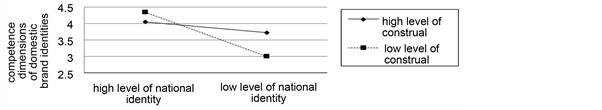

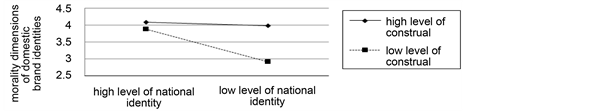

Furthermore, we examined the interactions effects on competence and moral dimensions of domestic brand identities. An ANOVA on the competence dimensions of domestic brand identities yielded a significant interaction, F(1, 56) = 4.74, p < 0.04, η2 = 0.078 (see Figure 2). However, the interaction effects on the morality dimensions of domestic brand identities were not significant, F(1, 56) = 2.23, p > 0.1 (see Figure 3).

Figure 1. The interaction effects of national identity and construal level.

Figure 2. The interaction effects of national identity and construal level.

Figure 3. The interaction effects of national identity and construal level.

A logistic regression analysis indicated that the evaluations of competence dimensions of domestic brand can affect consumers’ choices T-shirts (χ2 = 7.05, p < 0.01). In addition, national identity had a significant effect on the choice of T-shirts. Individuals with high level of national identity were more likely to choose the T-shirts related to the in-groups (χ2 = 4.49, p < 0.05; Mlow national identity = 33.3%, Mhigh national identity = 60.6%).

4. Conclusions and Discussions

The negative effects of an overseas brand crisis will spill over into the domestic brands in real life. To this phenomenon, this article explores the factors that can inhibit the spillover effects of overseas brand crises. The article finds that high level of construal and national identity can help domestic brands defend the negative spillover effects of overseas brand crises. Firstly, consumers with high level of national identity evaluate the moral and competence dimensions of domestic brand more favorably than consumers with low level of national identity under the context of overseas brand crises. Secondly, to consumers with low level of national identity, they evaluate the competence dimension of domestic brands more favorably when they are at high level of construal than at low level of construal. Finally, consumers’ choices of products can be affected by their evaluations of competence dimensions of domestic brands rather than the evaluations of moral dimensions of domestic brands.

According to our conclusions, enterprises should use the power of Internet to guide public to seize up an overseas brand crisis from a high level of mental construal, such that consumers tend to attribute the crisis to internal causes rather than situational factors. Once consumers attribute the overseas brand crisis to the central features of the overseas brand, their evaluations of domestic brands will not be influenced negatively and the spillover effect is reduced.

This study has some limitations offering avenues for further research. Firstly, in this article, we examine the negative spillover effects of overseas brand crises; however, positive spillover effects may exist as well. In the future, we can explore the boundary conditions of positive spillover effects of overseas brand crises. Second, we examine the factors for inhibiting negative spillover effects in this article, but we did not find out the most effective coping strategies while dealing with this spillover effects. Future researches can do research on the coping strategies of spillover effects.

Acknowledgements

This article is supported by “the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities”.

Cite this paper

Li, Q. and Jiang, Z. (2017) Study on the Spillover Effects of Overseas Brand Crises. Journal of Service Science and Management, 10, 388-393. https://doi.org/10.4236/jssm.2017.104031

References

- 1. Tajfel, H. and Turner, J.C. (1986) The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. In: Worchel, S. and Austin, W., Eds., Psychology of Intergroup Relations, Nelson-Hall, Chicago.

- 2. Petriglieri, J.L. (2011) Under Threat: Responses to and the Consequences of Threats to Individuals’ Identities. Academy of Management Review, 36, 641-662.

https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0087 - 3. Liberman, N. and Trope, Y. (1998) The Role of Feasibility and Desirability Considerations in Near and Distant Future Decisions: A Test of Temporal Construal Theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 5-18.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.5 - 4. Agrawal, N. and Wan, E.W. (2009) Regulating Risk or Risking Regulation? Construal Levels and Depletion Effects in the Processing of Health Messages. Journal of Consumer Research, 36, 448-462.

https://doi.org/10.1086/597331 - 5. Fujita, K., Trope, Y., Liberman, N. and Levin-Sagi, M. (2006) Construal Levels and Self-Control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 351-367.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.3.351 - 6. Kyung, E.J., Menon, G. and Trope, Y. (2010) Reconstruction of Things Past: Why Do Some Memories Feel So Close and Others So Far Away? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 217-220.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.09.003 - 7. KÖrner, A. and Volk, S. (2014) Concrete and Abstract Ways to Deontology: Cognitive Capacity Moderates Construal Level Effects on Moral Judgments. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 55, 139-145.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.07.002 - 8. Bilewicz, M. and Kofta, M. (2011) Less Biased Under Threat? Self-Verificatory Reactions to Social Identity Threat among Groups With Negative Self-Stereotypes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41, 2249-2267.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00802.x - 9. White, K., Argo, J.J. and Sengupta, J. (2012) Dissociative versus Associative Responses to Social Identity Threat: The Role of Consumer Self-Construal. Journal of Consumer Research, 39, 704-719.

https://doi.org/10.1086/664977 - 10. Freitas, A.L., Gollwitzer, P. and Trope, Y. (2004) The Influence of Abstract and Concrete Mindsets on Anticipating and Guiding Others’ Self-Regulatory Efforts. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 739-752.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2004.04.003 - 11. Mael, F. and Ashforth, B.E. (1992) Alumni and Their Alma Mater: A Partial Test of the Reformulated Model of Organizational Identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 103-123.

https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030130202 - 12. Phalet, K. and Poppe, E. (1997) Competence and Morality Dimensions of National and Ethnic Stereotypes: A Study in Six Eastern-European Countries. European Journal of Social Psychology, 27, 703-723.

https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199711/12)27:6%3C703::AID-EJSP841%3E3.0.CO;2-K - 13. Lee, R.M. and Robbins, S.B. (1998) The Relationship between Social Connectedness and Anxiety, Self-Esteem, and Social Identity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45, 338-345.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.45.3.338