Journal of Service Science and Management

Vol.7 No.1(2014), Article ID:43092,16 pages DOI:10.4236/jssm.2014.71004

Towards Sustainable Tourism Development in Zambia: Advancing Tourism Planning and Natural Resource Management in Livingstone (Mosi-oa-Tunya) Area

Department of Landscape Studies, Tongji University, Shanghai, China.

Email: floydmwanza@gmail.com

Received November 29th, 2013; revised December 31st, 2013; accepted January 28th, 2014

ABSTRACT

Over the last few decades, development policy has been dominated by mainstream economic theories that focus on economic growth to achieve sustainable development. The pace and scale of tourism growth in Livingstone (Mosi-oa-Tunya) area in Zambia have seen over reliance on natural resource utilisation by mass tourism developments. Compounded by insufficient planning and limited co-ordination and collaboration among the institutions involved in the tourism sector, tourism can have a negative impact and can create conflicts. Tourism growth in Livingstone (Mosi-oa-Tunya) has predominantly focused on the economic incentives in tourism and ignored the social perspective and impact on the local population. In general, the government agency administration structures affect the successful implementation of tourism policy and planning for sustainable tourism development. Given the fact that the limited government support, funds and appropriate knowledge in tourism limit Livingstone (Mosi-oa-Tunya) to develop as a sustainable “green” destination and remain an enormously difficult task to achieve.

Keywords:Natural Resources; Planning; Sustainable; Tourism Policy

1. Introduction

In an effort to reduce the negative impacts of conventional tourism, more environmentally and socially conscientious approaches were promoted to tourism. Typically called “ecotourism and sustainable tourism” though other terms such as responsible tourism, nature based tourism, green tourism, and alternative tourism are also used [1]. Any tourism destination without an adequate plan for development that addresses the economic as well as social and environmental functions of the industry is under prepared for the impacts of visitors, catastrophic events, and enforcing market forces [2]. Tourism requires a great deal of infrastructure including hotel road parking lots and restaurants which typically brings a number of negative consequences [1], such as increased pollution levels, the destruction of natural habitats, the displacement of natural wildlife and undesirable influences to once remote cultures [3]. As an alternative to conventional tourism, sustainability and ecotourism has continued to gain momentum over the last two decades [4]. Planning for sustainable tourism development refers to environmental preservation planning and as such includes a variety of inquiry activities and analysis to the decision for determining the direction of the development [1,5]. Tourism planning is advanced to prevent the intensive utilisation of resources in some specific areas without previous care for the preservation of the resources [6]. There has been an increasing need for landscape planners to consider methodological approaches to tourism planning and a number of techniques, principles, and examples that have evolved and recommended [7-9]. Nevertheless, the multiplicity and heterogeneity of tourism stakeholders render the process complicated [10]. A key component to the success of sustainable “green” tourism is local control in the planning, development and management of these tourism sites [11]. Arguably, Livingstone has the highest concentration of tourism activities in Zambia [12], although many authors have examined various aspects of general economic planning viability. A literature review of tourism sector shows that, with few exceptions, most studies in the past have focused on research in tourism marketing [13], and that many now incorporate new theories and concepts for better provision of tourism [14]. Bearing in mind the above, this study aims to contribute to better understanding of how tourism development planning is carried out and the inherent difficulties are associated with the implementation. It aims to explore and examine what is happening in Zambia. Therefore, this study attempts to record and analyze the factors affecting the development of the Livingstone (Mosi-oaTunya) tourism region. It compares planning and implementation of the national and regional tourism policies and strategies and attempts to show the conditions, which affect the course of implementation and cause its divergence from sustainable national policies and regional planning objectives. It considers the processes of translating objectives to outcomes and investigates why those processes fail to translate many objectives to practice.

2. Literature Review/Background Information

First, Zambia’s tourism industry relies on two primary assets: the Livingstone (Mosi-oa-Tunya) area and the country’s wildlife estate in 19 national parks, Game Management Areas (GMAs) and game ranches Zambia Development Agency [15]. The Livingstone (Mosi-oaTunya) Falls site appeals to a large tourists range of approximately 138,830 visitors more than the safari product of 61,000 visitors in 2009 Ministry of Tourism Environment & Natural Resources & Zambia Tourism Board [16]. Livingstone tourism activities are relatively far developed, compared to other regions in Zambia, [15]. Livingstone Mosi-oa-Tunya has a large proportion of Zambia’s adventure tourism capacity [17]. A recent [18] publication elaborates that between 2010 and 2030 arrivals to emerging economies will increase at double the rate. As a result, the market share of emerging economies such as Zambia has increased from 30% in 1980 to 47% in 2011 and expected to reach 57% by 2030 to over one billion international tourist arrivals [18]. However, to meet sustainable tourism, scholars argue that sustainability has largely been used conceptually as a “good idea” but has been difficult to enable through specific initiatives [4]. The task is more difficult in view of the multiple crises faced by the world. Recession, climate change, fuel crisis, food crisis, and water crisis, planning and governance become topical issues [19]. Consequently, the impetus for many of the current initiatives in tourism and international development stems from Agenda 21, a comprehensive program of action for attaining “sustainable development” in the 21st century [20].

International tourism destinations particularly those rich in biodiversity have in recent years caught attention of the global environmental movement because of resource degradation [21].

Arguably, community based planning approaches are promoted for tourism development as a prerequisite to sustainability [5,20]. Reference [22] observed that many destinations are now pursuing strategies that aim to ensure a sensitive approach when dealing with tourism. [8] refers to sustainable tourism development is an enormously difficult task to achieve in developing countries, without the collaboration of the international agencies such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Reference [23] observed the rise of sustainable tourism discourse in Southern Africa and has seen the development of a multiplicity of tourism projects packaged under ecotourism as a more sustainable form of tourism than mass tourism. The term “sustainable tourism” can mean different things to different people, often according to the position of the individual stakeholder. It is important to elaborate tourism planning with a definition of some principles of sustainable tourism [24,25]. More recently, the WTO defined “sustainable tourism” as follows: “Sustainable tourism development meets the wishes of present tourists and host regions while protecting and enhancing opportunities for the future.” As [7] stated, achieving sustainable tourism is a continuous process and it requires steady monitoring of impacts, introducing the necessary preventive and remedial measures whenever necessary [25].

Furthermore, sustainable tourism is now an approach at the international level that is advocated to be adapted to prepare all types of tourism to be environmentally, socially and economically beneficial [26-28].

Tourism in Zambia

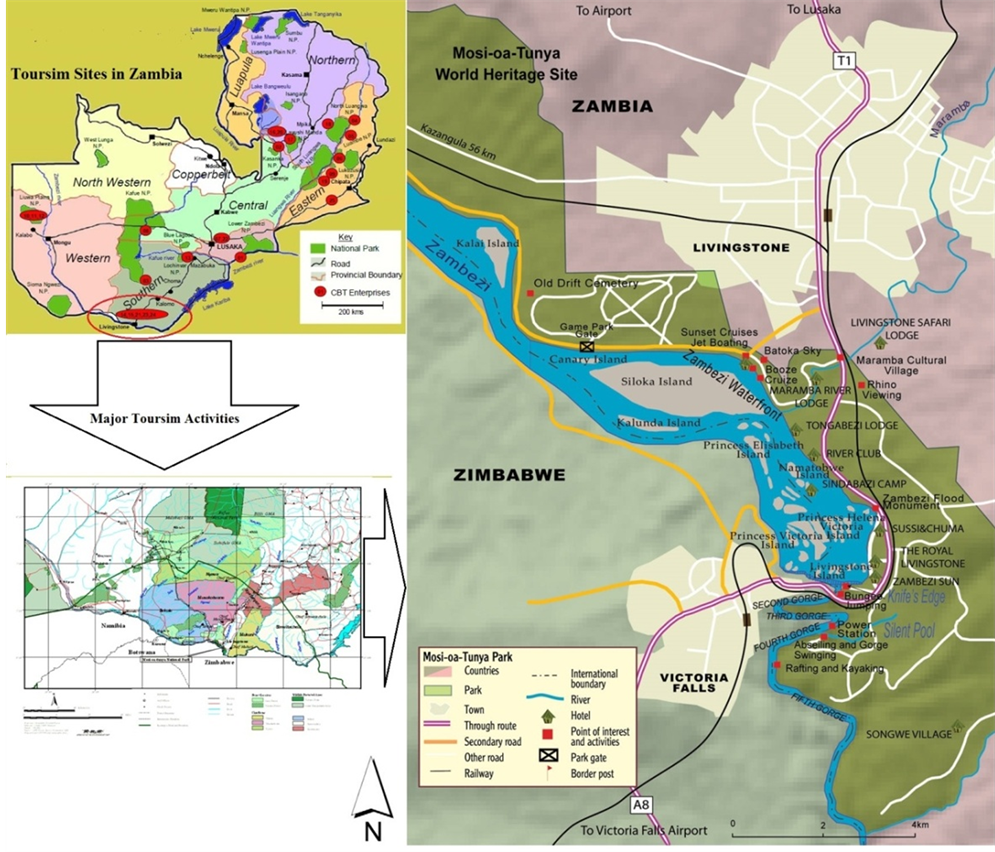

Zambia’s protected area network covers 30% of the country (224,075 km2) for which Zambia Wildlife Authority (ZAWA) is responsible [12].

The 19 National Parks covering 6587 km2 (28%) and 32 Game Management Areas (GMAs) 160,488 km2 in extent or 72% of the country’s PA network a huge resource forms wilderness tourism supply side [29-31]. Many of the tourism activity centres on the 19 National Parks covering 63,587 km2 (28%) and 32 Game Management Areas (GMAs) of 160,488 km2 in extent, or 72% of the country’s protected area (PA) network [29]. Many national parks landscapes and fauna form the basis for lucrative tourism and hunting industries in Zambia [30].

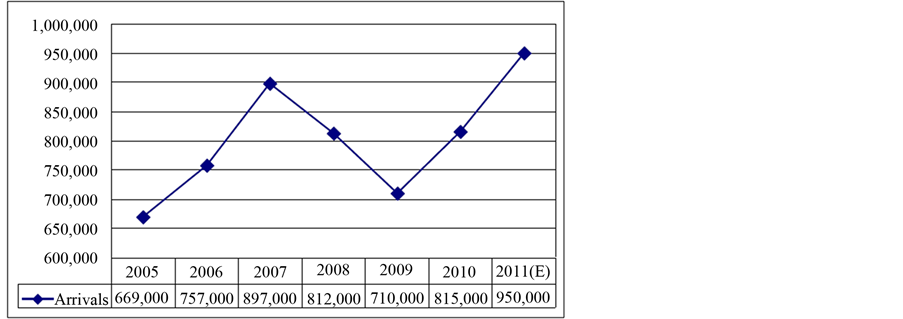

According to the [32] tourism activity created 44% of employment in the hotel and restaurant industry compared to 7% in the mining industry, 99% in agriculture and 66% in manufacturing. In 2010, the number of arrivals in Zambia was 815,000 and increased to 920,299 in 2011 as shown in Figure 1.

Zambia’s tourism industry established itself in the 1950s, [17]. As shown in Table 1 Zambia’s tourism indicators in years. There have been some significant changes in strategic and policy levels in Zambia, all of which have the potential to influence the sustainable tourism planning agenda [33].

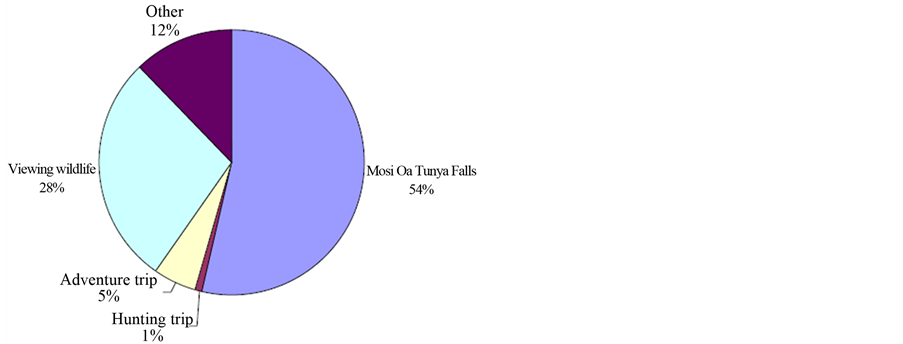

However, the extent to which these changes have infiltrated into implementation of local government is an area that requires further investigation [34,35] and the holistic involvement of communities in effective utilisation of their environmental assets and cultural heritage. The basis for this stance stems from the factor that tourism is increasingly Livingstone major economic activity. According [16] Zambia’s stake in the industry has been insignificant, but the past five years or so have witnessed a steady growth in the tourism sector, projected to deliver over 1.4 million tourist arrivals by 2015. [17]. Following Figure 2 provides more detail on the purpose of holiday visits, suggesting that more than half Zambia’s holiday makers (54%) arrive with the intention of visiting Livingstone’s Mosi-oa-Tunya only [36].

Zambia’s major tourism supply side clusters have developed in only a few key urban and national park locations, with a strong bias to the Livingstone region that offers nearly 40% of all nature tourism [15]. The effects of uncontrolled tourism development degrade ecosystems can be negative [37,14]. Nowhere in Zambia is this more evident than in Livingstone Victoria Falls (Mosi-oatunya) tourism site [38]. This underscores the need to entrench sustainable tourism planning principles in tourism management plans well before development begins and irreparable damage are incurred [39,40].

3. Research Site Profile and Characteristics

3.1. Study Site Location

Livingstone (Mosi-oa-Tunya) was purposefully selected

for the study because; it is among the sites being developed under the Livingstone Tourism Plan in Zambia [41]. Furthermore, the area is the earliest to be established in the region as a sustainable destination [42] and as a result, was due for evaluation.

The region derives its name from the waterfall locally known as the “Mosi-Oa-Tunya” meaning “The Smoke that Thunders”. David Livingstone from which the Livingstone town is named after then named the waterfall “Victoria” after Victoria, the British Queen [29]. The size of the park is about 6555 hectares or 66 square kilometers lying between latitude 17˚49' South to 17˚54' South and longitude 25˚41' East to 25˚55' East and an attitudinal range of between 900m to 925m above sea level [41].

3.2. Demography and Socio-Economic Characteristics

Livingstone Victoria Falls (Mosi-oa-Tunya) is in Southern Province of Zambia. Established in 1971 and declared a National Park in 1972 [42]. With an estimated population of 136,897 [32] and approximately has over 6000 visitors per day [16]. They contain biodiversity of global significance and is listed as Critical Sites (including Critical Habitats) [43]. There are around 4590 plants confined to this area, together with 35 endemic mammals, 51 endemic birds, 52 endemic reptiles, 25 endemic amphibians and an unknown number of endemic invertebrates [43,44]. It is approximately 20 km long and a maximum of 5 km wide [41]. It is constricted centrally to approximately 0.5 km (500m of land) [41]. Figure 3 shows the location map for Livingstone Mosi-oa-Tunya area; One of the overriding concerns about tourism in Zambia is that the tourism product relies heavily on the natural and physical environment [42,45,46]. Reference [8] highlighted that unsustainable tourism activities can affect the future viability the tourism sector, conserving of natural resources has become important through planning [47,48]. “Governments have become extremely canny in reproducing the sustainable development rhetoric without actually effecting fundamental policy and legislation changes [20].” In Zambia the need to understand the impacts of tourism has become important within a planning context because of the many statutory requirements such as the [41,49,50] and global demand for sustainable tourism [25].

The Zambian tourism sector is guided directly and indirectly by 11 pieces of legislation [51]. These tourism plans have focused merely on maximising foreign tourists’ receipts and thus increasing the supply capacity of the tourism industry [14,52]. The main shortcomings are due to sectorial planning done in isolation, communication and co-operation among related bodies are sparingly weak and in most cases do not exist [34,53-56]. It is only right that development and land management is supported by a holistic planning [57-60]. It is reported that these common shortcomings in present tourism development approach pose challenges to sustainable tourism development in Zambia [35,54,61,62]. As observed by [8,63-65] the study is premised on the assumption that, local government agencies and communities to influence the sustainable tourism planning agenda. However, the extent to which tourism policies has infiltrated into local tourism agencies and communities is an area that requires further investigation. The following section outlines the methodology used to survey local agencies and communities to ascertain responses to tourism policy and planning implementation in Livingstone (Mosi-oa-tunya) area.

4. Methods and Procedure

4.1. Research Design

The research conceptual framework was developed based research methods for assessing local authorities participation in tourism policy and planning similar to studies done by [10,63,64]. Given that the purpose of this paper is to identify and evaluate tourism policy and planning implementation for sustainable tourism development by government tourism agencies in Livingstone (Mosi-oatunya) area. A qualitative descriptive approach was employed and quantitative data where appropriate. The study used the non-probability sampling design to collect data from local tourism authorities and agencies. As cited in [66], the purposive sampling technique was found to be adequate and appropriate for such a survey research. In view of the facts given above, the purposive sampling method was adopted. Interview guides and questionnaires were the instruments used for data collection. The

interviews and questionnaire administration was made to government tourism agencies (MTENR/ZAWA/ZEMA) and local Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) representatives. In addition, institutions related to the Zambian tourism industry were also contacted for requisite information and data. To capture a significant number of tourism planners in the population sample, data were collected from tourism agencies at the Lusaka Ministry of Tourism Environment Natural and Resources, Zambia Wildlife Authority in Lusaka’s Chilanga headquarters, Zambia Tourism Board Lusaka and Regional Local ZAWA branch in Livingstone (Mosi-oaTunya) area. Livingstone greater area community leaders of Community Resources Boards (CBR) agencies and popular lodges, tourism enterprises and guesthouses make the local community group. The research was conducted from 22nd November 2012 to 5th April 2013.

All the in-depth interviews were conducted at places of choice by the interviewees in the various departments and communities. The interviews were conducted by the corresponding author.

4.2. Data and Sources

In view of the facts given above, the purposive sampling technique was found to be adequate and appropriate because there was no sample frame of all respondents. Since it was an exploratory study, the rationale of the data collection was to ascertain government agencies and community heads’ roles in tourism policy and planning participation in the sustainability framework implementation for the case of Zambia’s Livingstone greater area. The survey employed three major methods, personal questionnaires, interviews of identified key actors in the Zambia tourism planning process and the local tourism businesses and local tourism authorities. The purpose however, was to generalize from a sample to the population in order that inferences could be made about the involvement of government agencies and th communities in tourism policy and planning development [67]. Secondary sources from literature review of books, journals and grey reports. Grey reports were used due to limited research publications concerned with tourism planning in developing countries such as Zambia. Past reports and any other material related to plans and policies for the tourism development of Livingstone were reviewed.

4.3. Sampling Procedure and Study Instruments

Based on the actors’ group, a list of government tourism heads and local community representatives was compiled and used as a sampling frame for the selection of the respondents. A self-completion questionnaire survey was emailed to solicited sample list of local tourism authorities and planners in Zambia, who have direct and indirect involved in the Livingstone tourism master plan. A realtime online-based questionnaire website [46] was used to improve response and analysis of findings. The onlinebased survey enabled a degree of tracking and gauge findings and easy clarifications and adjustments in cases where the questionnaire was not well-defined. To encourage survey completion and to confine the aims of the survey to specific tourism planning objectives (such as identification of sustainable tourism planning implementation and development in tourism strategies), without eroding the aims of the investigation, the survey design incorporated a combination of closed and open questions which was also hosted online to improve survey responses and participation. Closed questions were utilised to gauge responses to straightforward questions, where a simple tick box suffices to assist in classification of respondents. However, recognizing the small sample specific population involved in this survey, a range of open questions were included to generate a source of more qualitative, explanatory information that can add a richer dimension to understanding responses. Hence, the fieldwork aimed to interview representatives of the major groups. It was designed using a series of semi-structured interviews with key actors. Reference [68] explained the criterion used to determine sample size is an important issue in research. The study uses descriptive data analysis and explanation, and the use of appropriate theory to help explain events [69,70].

4.4. Assumptions and Limitations

The study was based on the assumption that surveying experts with knowledge of the case study sites would be a reasonable way to obtain an up to date overview of site. However, this approach may have a few limitations, including:

• Bias of the expert’s personal opinion;

• Interpretation of other stakeholder’s views by a third party;

• Incomplete knowledge of the site (including of impacts, challenges and dynamics between stakeholders);

• Some experts had not been back to the site in the last two years.

This assumption and limitation were in part addressed by the desktop review of documents, which often served as a complement to the information provided by the experts.

4.5. Target Population and Sample Size

The target population for the study was government tourism agencies and local community heads or their representatives in the selected communities. A total of 85 questionnaires from 165 sent questionnaires were filled in for this particular study, 9 in-depth face to face interviews were carried out with persons involved in the policy making process and the implementation of tourism related plans. As shown in Table 3 the 85 respondent population comprised 12 local communities (CBNR) and consultants and 73 tourism planners/local authorities as shown in Table2 Surveys were mailed directly to the planning officers or agencies (MTENR, ZAWA, ZTB, ZEMA and National Heritage Conservation Commission (NHCC) who oversee on tourism planning processes and understand how tourism fits into local development plans for completion. 43 respondents completed and usable questionnaires were returned, yielding a response rate of 51%. The aim of the survey was not to produce large amounts of statistical analysis, rather to generate a picture of current levels of sustainable tourism planning at the two levels (local and regional), which is descriptive in exploring the small population size. Given that this figure represents half of all local authorities, the information the survey yielded is considered valid in providing a general picture of sector responses to tourism planning in Zambia.

4.6. Attitudes towards Tourism Development

The patterns of response provide a useful geographic spread of data, and represent a good mix of respondents. The low response rate at community level at 25%, explained primarily by the apparently delegated role of tourism planning by the local level of regional agencies and cross cutting issues, and whose main concerns relating to tourism are integrating resource management issues under (ZAWA/ZEMA/MTENR), particularly water and waste management. The respondents and their abilities to conceive the questions and to answer precisely varied not only from one group to another, but sometimes from one respondent to another in the same group. The gap in the level of knowledge, experience, and tourism planning development backgrounds and quality of information influenced the answers and the views of the respondents and thus the results obtained. At regional or both provincial and city levels, the response rates were over one half of the population (55%). Methodologically, this study suffered from the same problem as most online and mailed surveys, and while the overall response rate is satisfactory (often online and mailed 30% response rate is deemed reasonable for such surveys, for an online/ mailed survey, conventionally, a response rate of 20% is considered as a good response rate, while a 30% response rate is considered to be good [71]. It is difficult to assure the representativeness of the responses achieved. The non-respondents included 7 (Consultants & Planners) (out of 15) and 26 (local community & district planners; while for (ZAWA main branch) and regional planning offices the non-responsive figure was 9 (out of 12). Some 28 responses were received from MTENR Lusaka 49% response), while 15 responses were received from the Livingstone (54% response). Overall, the responses received provide a satisfactory sample in relation to tourism areas, population size and geography, all of which will be further elaborated in the findings. Longitudinal comparisons are only possible at the general level, given that although the same population was sampled, not all respondents answered the surveys. Lastly, it should be noted that, the names of specific government tourism departments are not given in the discussion of findings from the survey to respect the confidentiality of the research process, which was assured in the research process in order to get accurate responses.

5. Results and Discussion

The findings of the survey are reported using a combination of descriptive and quantitative data given the small population, with verbatim responses to open questions to enrich the data and provide further insights. As a first step, it is valuable to recognise the scale and type of communities, areas and tourism profiles represented in these findings, particularly as such variables are useful in cross tabulating findings. The resident population of the survey areas at present population was estimated at 136,897 inhabitants at the 2010 census [32]. With reference the surrounding areas that make the largest populations, are made up of Mukuni’s village on the eastern and South-Eastern border, Sekute Chiefdom (Simonga area) on the West, Imusho village to the western boundary of the park and Chief Musokotwane on the North-Western boundary are in Southern Province of Zambia, with an average population density of below 15 people km2 residents with a total estimated population of 778,740 persons in Southern province alone [32,30].

5.1. Tourism Policies

Local and regional authorities were asked if they had knowledge of the Zambia Tourism Policy. There is no statutory requirement for a Tourism Policy, the publication of one indicates a strong community interest and local government commitment to tourism, the survey revealed that 26 tourism institutions under at the three levels of planning and implementation level have knowledge of the tourism policies and other strategies. Table 3 shows the comparison of the survey groups indicating the different types of organisational levels and knowledge on tourism policy and related strategies developed towards the tourism sector in Zambia.

The survey respondent’s percentage outcome based on proximity to the study site revealed a lower understanding of the Tourism Policy. The respondents’ percentage figure trends shows 33% of CBNRM respondents had knowledge of the policy and the trend rise in the knowledge of Tourism Policy and strategies by a significant rise at the main government ministry of tourism and government department agency ZAWA. This would appear to indicate that the effect of the national tourism strategy better understood at the core ministry and department and less appreciated or limited knowledge at local community level to develop and adopt strategies. Respondents with no knowledge of the Tourism Policy stated that all tourism matters delegated to the MTENR or ZAWA. Findings suggest that despite major tourism activities taking place in Livingstone and its surrounding areas, the local population have never come across the earmarked Livingstone greater area plan for sustainable development, but could be encouraged if they had one. This could explain the reason for low response from at local community level, and indicates a lack of interest in tourism development issues at this level, where tourism planning and policy issues were delegated to other bodies at ZAWA and MTENR.

5.2. The Influence of the MTENR/ZAWA Tourism Policy for Zambia (TPZ)

The majority of local tourism authority planning officers at local and government department (MTENR/ZAWA) level who had knowledge of the already existing tourism plans and had seen the Livingstone greater area plan, 83% of respondents had indicated how the Tourism Policy for Zambia (TPZ) would inform their own policy

Table 3. Tourism government agencies & actors’ respondent’s percentage response, by author (2013).

development. Responses from the local tourism authorities thought that there were emerging tourism issues that needed to be included in a future revised policy such as ecotourism certification, “green tourism”, and sustainable tourism practices. Five respondents indicated the need to incorporate elements of the five year national development plans such as the [53,72,73], where appropriate to reflect particular locality and for easy implementation. While a further three stated that, they would take the plan lacked in implementation process due to institutional limitation and resources considered.

Two respondents stated that the TPZ was approved in 1997 and published in 1999, does not reflect the current organisational structures and governmental existing plans, while a further three stated that the turnaround strategy plan directly aligns with the national sustainable strategies [12]. Others commented on specific elements of the national plan and appreciated the opportunity to determine the national context and direction of tourism strategy in Livingstone Zambia and the replicability of the pilot plans such as the Livingstone greater area development plan and for a common approach to core issues as set WTO’s universal tourism standards. Overall, though, the ways in which the TPZ has already influenced, or will influence, policy at a local level appear vaguely stated in many cases.

5.3. Planning for Tourism Impacts in Livingstone

Some 57% of respondents raised specific tourism issues that need redress in the next review of the Tourism Policy Zambia. The responses as illustrated in Table 4 and in some cases, respondents gave more than one reaction. The range of emerging tourism related issues raised indicate two approaches to tourism development. These approaches are not polar opposites, but do represent different perspectives on tourism activity. On one side are those authorities that have concerns about the impacts of tourism, where key policy issues relate to balancing the needs of locals, visitors and other interests, dealing with impacts arising directly from tourism activity, and managing environmental resources (36% of authorities). A particular concern indicated by three council representatives is that of the cost of developing and managing tourism opportunities, activities and impacts. Two of these indicated impending studies to ascertain the economic cost of infrastructure and attractions, while a third noted

the difficulties for councils with small populations to afford infrastructure improvements through the local rates system. 16% of respondents were conversely more concerned about developing tourism assets, promotions and infrastructure in an attempt to generate or meet the demand. Some 40% of respondent did not have any tourism issues of concern. The response may hide a number of more insidious issues, some local agencies do not possess the tourism expertise to identify and deal specifically with tourism impacts, while others may be more focused on championing the marketing orientation of Tourism in generating economic benefits, considering that policy literature focus on poverty reduction strategies. In many cases, there are significant dangers that negative impacts are not anticipated, mitigated or managed. Worth noting though is that 57% respondents identified tourism related issues that needed to be addressed the study. These findings indicate a growing interest and concern about the effects of tourism and the need for local tourism planning authorities to address impacts, both positive and negative, through the planning system. In addition, the range of issues identified, suggesting either a higher level of tourism awareness within councils or the emergence of a more extensive number of impacts.

5.4. Importance of Tourism in Livingstone

As indicated in [16,74] “74.9% of foreign tourists, who have had the opportunity to visit Zambia’s popular tourism destinations”, visited Livingstone Mosi-oa-Tunya area. Other popular destinations included South Luangwa National Park (24.3%), Mosi-oa-Tunya National Park (25.4%), Lake Kariba (26.5%) and other National Parks and Game reserves (26.5%) [16]. These destinations are Zambia’s most developed and marketed attractions [75-78]. Respondents were asked to indicate if the perceived importance of tourism in the case of Livingstone. Some 50% respondents stated that the importance of tourism had increased, 17% of these stating increased significantly. The main reason given for this was the increasing recognition of the realized and potential economic benefits of tourism within the local tourism areas. It appears that many tourism stakeholders have become more aware of the beneficial effects that tourism can bring to a locality through as a source of revenue, business development and employment opportunities. In particular, the awareness of the ability of events to draw visitors to an area appears to have strengthened. Other contributing factors included growth in tourism, improved marketing and strategic vision, development of new products and services, and more central government funding. Only 7% respondents stated that the importance of tourism had decreased, partly due to the limited tourism appeal of one location but in two others a perceived lack of value, for example: Zambia Tourism Board ZTB have been unable to demonstrate, articulate and quantify the value in monetary terms. 26% of the respondents stated that the importance of tourism remained the same. This was explained by several locations where tourism activity remained static or where growth was limited by infrastructure constraints. One issue identified was the absence of effective tourism organisations and regional co-ordination to take tourism developments forward and to illustrate the benefits of tourism to the local communities, thereby not propelling tourism forward as a beneficial economic activity. Development of new attractions and recognition of substantial increases in visitors were cited as the main reasons for the increase in importance. This appears to indicate that tourism area have a clear understanding of how tourism can benefit their locality, which may have resulted from the key messages in the national tourism plan and associated reports. However, similar issues with regard to lack of financial support given to tourism or lack of importance placed on tourism activities.

5.5. Future Tourism Development

The range and scope of developments (78.6%) indicate a significant rise in the tourism infrastructure across the country, from airport enhancements to visitor trails. The most developments, which had taken place in three local communities in Livingstone (Mosi-oa-Tunya) area followed by accommodation development (non-hotel) in 30 areas (71.4%) [15]. It has been reported that the total number of tourists to Zambia is expected to reach more than 1.4 million tourists in by 2015 and these will require more hotel establishments in the country [15].

The development of new attractions at all levels suggests vibrancy in tourism development. In terms of the types of new developments, the list of new attractions, facilities and services on offer is considerable and far too extensive to include, but incorporates a large proportion of new trails, tours, guided walks and outdoor adventure activities, with a smaller amount of development to create or upgrade cafes, hotels, museums and retailing. All of which utilise environmental resources and all of which have the potential to create or exacerbate adverse impacts. As such, the role of the ZAWA in controlling the effects of tourism development is clear in a climate where growth in individual adventure tourism enterprises and outdoor pursuits is occurring. Some 44.2% of respondents considered local communities in the Livingstone area to be under pressure from increased tourism and Table 5 show the major pressures highlighted by respondents. Three broad categories of responses are distinguishable through examination of a subsequent open question on what pressures existed in localities.

Table 5. Tourism planning pressures created in Livingstone greater area, by author (2013).

First, specific locations were identified as likely to experience increased visitor numbers and associated impacts, e.g Mukuni’s village on the eastern and Inyambo local tourism Community Development Trust areas. Second, the concerns arising from increased visitor numbers were identified including, demand for infrastructure, construction of tourist-related ventures, dealing with municipal waste, water demand and waste water disposal.

Increased freedom camping and effects on wildlife and natural areas, housing affordability, second homes and subsequent loss of community culture attributes, increase in tourist arrivals (e.g. Livingstone’s newly extended Harry Mwaanga Nkumbula International airport expansion).

Third, and somewhat in contrast to the latter responses, a grouping of respondents though smaller than the latter, want to grow tourism and maximise the benefits, through creating infrastructure, building more accommodation and increasing the workforce. The survey identified that respondents in areas with the largest number of guest at night of over 5500 in the peak month were more likely to report that their area was under pressure from tourism. Correspondingly those with the smallest number of nights (less than 1000) were the least likely to be under pressure..The areas under pressure tend to include those reliant on the natural environment, cities, areas on the main tourist routes and National Parks. Those not under pressure includes those wishing to develop tourism currently with low visitor numbers and those off the beaten track. Interestingly, 73% local tourism area authorities at (ZAWA, NHCC) respondents (Southern Province region) perceived Livingstone greater areas to be under pressure compared with 29% at central government department at MTENR. Explanations for the perceived higher pressure on the South include respondents’ personal experiences in conjunction with often heavy concentrations of packaged tourism and adventure tourism utilising the physical and natural environment.

5.6. Linkages and Synergies Planning (MTENR/ ZAWA/NHCC/ZEMA)

Under Zambian laws consents are required for all tourism developments. Consents are issued by multiple central governmental departments, regional and local authorities and communities depending on the scope of the consent sought [60]. Ascertaining accurate data on tourism related resource consent applications is highly problematic. While many respondents were able to give precise numbers in relation to resource consent applications and refusals, a significant 13 respondents were not able to provide the data. The main reason given for this is that tourism is not always isolated as a key variable in the database recording process for tourism enterprise concession consent applications. Some developments are not primarily designed for tourism purposes but may produce a tourism spin-off, e.g. development of a winery. In other cases, databases are not set up to be readily searched, data is not feed into system as “tourism”, but as “commercial activity” and in several cases, the detail of activity or data is not even kept. This seems to indicate an inherent problem in the data management of tourism enterprise concession consent applications with regard to tourism, and a technical inability to retrieve useful information that can inform tourism planning at local, regional and national strategic levels. Acknowledging the limitations of the data, the following results give a broad indication of the workings of the ZAWA process in relation to tourism development within local communities.

Twenty four respondents representing 56% had dealt with tourism enterprise concession consent applications since 2010. The highest number of applications dealt with by one authority was 40. Ten authorities had dealt with between 1 and 10 applications, six between 11 and 20 applications, five between 21 and 30 applications, and three had dealt with 31 or more applications. While the largest number of applications were dealt with by District Councils, participants in the process held the view that all of these tourism programmes are developed by a monoactor form of centralised administration, generally overlooking the knowledge, skills and goals of local tourism organisations, both public and private, 50% of the CBNRM accounted for 37% of tourism enterprise concession which still needed ZAWA approval, indicating a substantial number of applications within a small number of local communities taking the lead role in resource management. Some 76% of tourism concessions submitted were made to the now well established Mukuni Community Development Trust. The trust has established local progressive leadership and used African Wildlife Foundation (AWF) assistance to develop twelve lower level area boards, which is an encouraging result suggesting that local CBNRMs playing a role in receiving enterprise concession related to tourism might have a strategic vision of how tourism should develop in their locality. Importantly, most of the communities receiving large numbers of tourism enterprise concession did have some form of policy guidelines, although two respondents received more than 25 applications did not.

Further, 24% of enterprise concessions were submitted to a start up Sekute Community Development Trust without a tourism guidelines or policy. There is no particular pattern of number of tourism enterprise concession received and the visitor numbers in remote CBNRM areas, with the largest numbers of applications 8 of respondents at ZAWA with over 25 applications in a variety of rural and urban environments, representing those areas that are already important tourism hubs (3 of the 8) and those encouraging the development of a tourism economy (5 of the 8). 3 of respondents at ZAWA received no applications, all of which are in insignificant under developed tourism areas: two not on tourist routes and one within a provincial city environment. One might expect a relationship between those ZAWA provincial offices reporting a large number of tourism enterprise concessions and those reporting that they perceived their area to be under pressure from tourism but this was not the case. 8 ZAWA respondents reported 25 or more applications, 5 respondents stated that their area was not under pressure from increasing tourism. In fact of the 19 of respondents at ZAWA that reported their area to be under pressure, 9 respondents were not able to extract numbers relating to tourism pressure, one ZAWA respondent had never handled tourism enterprise concession applications. A further four respondents received fewer than 10 tourism enterprise concessions, suggesting that it is not necessarily new developments that are creating tourism pressures. Indeed, one might say that applications made under the post [12,50] strategy are perhaps less problematic than existing developments that already generate significant demand.

The notable major challenges identified in the survey include that of poor understanding of what is required in the application for tourism developments activities. Eight respondents 24% of those that had experienced difficulties with applications stated that applications are often presented with incomplete information and a further eight respondents 24% identified lack of understanding and requirements for the tourism establishments under [35,50] process to be a reason why problems are experienced in the application procedure. However, as one respondent commented, early contact with the authorities is important for the process to run smoothly for the applicant: “it is not as bad as they initially think”. Similarly, a further difficulty in applications is a lack of consideration of impacts of developments (18%). However, 21% of those that had dealt with ZAWA applications had not experienced any difficulties. As one respondent commented, “ZAWA act is there to protect the environment if a tourism developer follows carefully with ZAWA planning and guidelines/tourism experts, then things appear to go relatively smoothly. Communication between all parties is the key ingredient”. The relationship between tourism development, sustainability and the Zambia Tourism Policy and ZAWA act towards tourism, as stated by a respondent: “at the moment the MTENR Tourism Policy of 1999 and ZAWA act of 1998 deals with the sustainability of tourism on a case by case basis, however, at a strategic level the sustainability of tourism is not grappled with, due to outdated policy, legislation and planning”. It is also apparent that the Tourism Policy/ZAWA act does not necessarily assure a sustainable approach to tourism planning outside of the particular development under consideration. For example, one respondent noted that: “results from Zambia Tourism Policy and wildlife authority” has been beset with negative administration, transparency and accountability issues”. While it is unclear to what extent planning officers work with developers to ensure resource consents are granted, the general premise that there are few outright refusals begs the question as to whether the ZAWA process is rigorous in controlling the negative impacts of tourism in areas under pressure from increased visitor numbers. One respondent commented that “the two institutions MTENR and ZAWA are not a detractor to tourism development”, which may or may not be a good thing.

6. Implications

It is clear from the survey findings that the dual role of MTENR/ZAWA in performing a regulatory planning function and promoting tourism raises issues about potential conflicts of interest in applying the Tourism Policy, ZEMA and ZAWA acts while considering the economic development of a locale. This debate is an old one environment versus economics, but in a sustainable development context the need to protect environmental resources to ensure future economic stability is mandatory. It is clear from observations of local communities and authorities at local and regional offices have engaged more actively with the tourism sector through the development of tourism plans and policies. In order to have sustainable development as a national policy direction as reflected in policy developments in the revised sixth national development plans (SNDP: 2011-2013).

6.1. Roles and Integrations of Sustainable Strategies

The integration of Sustainable Development (SD) Strategy in Zambia’s National Development Plans’ legal framework, various legislation in support of SD developed such as, ZEMA act (2011) to address impacts through strategy preparation is encouraging. However, due inability of local community authorities to benefit directly from the limited resources, especially those with a small population base and limited ability to raise revenue through rates, providing infrastructure, promoting tourism growth and managing impacts are a financial burden on tight budgets from central government: this emerges as a clear theme in the survey. New legislation currently under consideration to minimise waste provides a refund to communities, this is one example of where finding ways to compensate local communities and ratepayers for the use of local services is clearly a challenge and for many councils in Zambia and, indeed, worldwide, juggling the economic costs and benefits of tourism and justifying the outcomes to ratepayers remains problematic.

6.2. Delayed Decentralization Tourism Planning

This study shows that local authorities understand the roles of the MTENR/ZAWA with regard to sustainable tourism, focusing on the effects of tourism activity within their area. “Looking at the bigger picture, one of the criticisms of haphazard sort of implementation due to silo national level planning” [79]. As such, while the intentions of ZAWA in preventing undesirable developments are laudable, the cumulative effects of a number of seemingly innocent, less damaging developments might be equally detrimental. Only one respondent specifically drew attention to this issue, but that does not detract from the importance of the point indeed it might be questioned whether planning officers are sufficiently aware of the dangers posed by this breach within ZAWA framework. Similarly, the focus of ZAWA on effects of activities, while well intentioned, could result in significant economic sectors, like tourism, not been adequately and proactively planned for. Somewhat worryingly, this might be reflected in the lack of response from regional agencies, who do not appear to take tourism as a specific concern under their remit, although are clearly concerned by the effects of tourism such as waste. The inherent difficulties of extracting tourism related projects from MTENR/ZAWA databases held by local tourism authorities appears to be an issue in understanding the implications of the ZAWA for tourism and the extent to which projects are acceptable in the local planning decisionmaking process. Quite clearly, this reflects the inadequacies within data management and retrieval, but also indicates a systemic challenge for the core workings of ZAWA, which by its nature is not concerned with specific industry sectors but with the effects of activities. While the key focus on natural resources provides a valuable framework for the development of appropriate policy and decision-making frameworks, the ability to understand the scope and scale of tourism-related developments is essential particularly given the ambitions of the proposed national tourism strategy (SNDP). Worthy of note is that of the 13 local authorities that were unable to retrieve tourism-related data due to technical problems of record keeping and searching were: four of the eight central government departments (MTENR) stating that their areas were under pressure from increasing tourism; further, two of Zambia’s new prime Lusaka circuit very significant local tourist locations; and, further again, three other well-known Livingstone tourism areas. These omissions from knowledge at a planning level indicate the potential to not fully understand the rate of tourism growth from a supply perspective and the cumulative effects of tourism development linked with local aspirations within the confines of long term national development planning (plans) and a budgeting system that is partially decentralised.

7. Conclusions

The continuing limited involvement of local communities and regional government authorities in tourism planning and development of sustainable tourism approaches existed, given “the continued conspicuously absence of documented national development planning policy and fragmented legislation framework of sustainability in Zambia’s national strategies”[60]. With the role of tourism in economic development established and recognised in statutory plans, sustainability now underpins sectorial policy framework for tourism in Zambia, and the landmark steps taken to develop and review national aspirations for tourism development will represent a step forward in establishing a clear remit for local government in planning for tourism. The extent to which this is rhetoric rather than reality is questionable, given the somewhat mixed results in the survey of local government agencies reported in this study. For Zambia a country emerging from a history of centralised economic planning, this question becomes even more vexed quite clearly, a range of pressures continue to affect local areas and the challenges that face many local communities in trying to manage the effects of tourism on environmental resources are as pressing as ever. A national tourism plan will enable local authorities and councils to evolve futures that befit environmental resource opportunities and constraints, community aspirations and local budgets. While tourism is mainly a private sector industry in Zambia, the public sector adopts a dual role as the gatekeeper of tourism developments through planning control, while promoting economic development opportunities through tourism.

As such, while councils have become the arbiters of sustainable tourism through their role in implementing the Zambia Tourism Policy, the appeal of developing the local economy places them in a dichotomous position. While much of this discussion sounds positive, there is still a major gap between strategy and implementation in the evolution towards Zambia as a sustainable destination. While sustainability is now one of the cornerstones under tourism strategy review, much of this lies at a national strategic level and remains as a philosophical stance. Evidence suggests that problems created by tourism pressures do exist and some of these are difficult to deal with given the poor linkages and synergies within the various tiers of government that undertake planning with limited budgets at local government. Pressure at key tourist hotspots and with certain tourism related activities are recognised and with the continuing growth in tourist numbers forecasted, the effects of tourism have the potential to change the nature of the tourist experience and the very foundations on which Zambian tourism is built. The existing problems of geographic concentration of tourism activity will only worsen, exacerbating the pressures on local authorities.

As argued by [64] “policy at a national level that assists local areas in dealing with volumes and the distribution of tourists in a more methodical manner”. With reference to [80-84] by enabling more proactive public sector approach to tourism planning, steps towards understanding the dynamics of tourism in Zambia made by the Ministry of Tourism Environment Natural Resource under the Zambia Wildlife Authority by establishing a strategic tourism development model. Given that local government agencies are politically weak, of well-recorded and entrenched patterns of corruption and patronage built around land and planning decisions, this call by planners has a greater degree of cogency as observed by [60,80,85] argue that, “those destinations, localities and nations that prepare to put into practice good detailed policies and strategic plans will reap the benefits for sustaining their tourism products in the future”, a cornerstone of Zambia’s tourism strategy. Further research and steps would help local Zambian destinations to ensure ZAWA achieves the goals and principles enshrined in the original legislation. Without a more concerted attempt to challenge pro-development policy, Zambia is likely to lose pace in terms of competitive advantage as a clean, green and sustainable tourism destination.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Alexandra Thorer & Roy Clarke (kalakikorner) for the assistance in making suggestions, corrections and to the would be referees for their valuable and helpful comments, which have improved the quality of the paper. Also, we extend our thanks to The Copperbelt & Tongji University, especially the Department Landscape studies.

REFERENCES

- A. Hansen, “The Ecotourism Industry and the Sustainable Tourism Eco-Certification Program (STEP),” International Relations and Pacific Studies, University of California, San Diego, 2013. irps.ucsd.edu/assets/021/8446.pdf

- C. Wu, “Sustainable Development Conceptual Framework in Tourism Industry Context in Taiwan: Resource Based View,” Conference of the International Journal of Arts and Science, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2009, pp. 1-11.

- C. A. Gunn, “Tourism Planning,” Routledge, London, 2002.

- B. Ahn, B. Lee and C. S. Shafer, “Operationalising Sustainability in Regional Tourism Planning: An Application of the Limits of Acceptable Change Framework,” Tourism Management, Vol. 23, No. 1, 2002, pp. 1-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00059-0

- UNEP, “Eco-Tourism in Wider Caribbean Region: AN Assessment,” Technical Report No. 31, Caribbean Environment Programme Technical, UNEP, Kingston, 1994.

- UNEP, “Environmental Codes of Conduct for Tourism,” United Nations, New York, 1995.

- World Tourism Organisation (WTO), “Guide for Local Authorities on Developing Tourism,” WTO, Madrid, 1999.

- C. Tosun, “Challenges of Sustainable Tourism Development in the Developing World: The Case of Turkey,” Tourism Management, Vol. 22, No. 3, 2001, pp. 289-303. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00060-1

- K. Andriotis, “Tourism Planning and Development in Crete, Recent Tourism Policies and Their Efficacy,” Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Vol. 9, No. 4, 2001, pp. 298-3016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09669580108667404

- V. M. Waligo, J. Clarke and R. Hawkins, “Stakeholder Involvement in the Implementation of Sustainable Tourism,” Journal Tourism Management, Vol. 36, 2013, pp. 342-353. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.10.008

- UNEP, “The Role of Local Authorities in Sustainable Tourism. Tourism and Local Agenda, 21,” United Nations, Rio, 2003.

- Zambia Wildlife Authority (ZAWA), “Annual Report,” Government of the Ministry of Tourism, Environment and Natural Resources, Republic of Zambia Kwacha House, 2007.

- V. Teye, “Tourism Development in Zambia: Some Physical and Environmental Considerations,” Invited Chapter in T. V. Singh and H. L. Theuns, Eds., Towards Appropriate Tourism: The Case of Developing Countries. Peter Lang (European University Studies), Frankfurt, (Revised and Expanded Version of “Geographical Factors Affecting Tourism in Zambia,” Annuals of Tourism Research, Vol. 15, No. 4, 1988, pp. 487-509).

- C. A. Gunn, “Prospects for Tourism Planning: Issues and Concerns A,” The Journal of Tourism Studies, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2004, pp. 3-7.

- Government of the Republic Of Zambia, “Tourism Sector Profile,” Zambia Development Agency (ZDA), Lusaka 2013.

- Zambia Tourism Board, “2010 Visitors’ Arrivals Analytical Report,” Ministry of Tourism, Environment and Natural Resources, Government of the Republic of Zambia, Kwacha House, 2011.

- World Bank, “Zambia Economic and Poverty Impact of Nature-Based Tourism,” Report No. 43373-ZM, Economic and Sector Work Africa Region 2007.

- World Tourism Organisation (WTO), “Tourism Highlights 2012” Calle del Capitán Haya, Madrid, 2012.

- United Nations Environment Programme and World Tourism Organisation, “Tourism in the Green Economy,” Background Report, UNWTO, Madrid, 2012.

- USAID and Sustainable Tourism, “Meeting Development Objectives, USAID’s Portfolio in Sustainable Tourism,” US Agency for International Development Washington DC, 2005.

- J. E. Mbaiwa, “Tourism Development, Rural Livelihoods, and Conservation in the Okavango Delta, Botswana, A Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation,” The Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University College Station, 2008.

- W. Jamieson, “Guidelines on Integrated Planning for Sustainable Tourism Development,” Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, 1999.

- S. Chiutsi, M. Mukoroverwa, P. Karigambe and B. K. Mudzengi, “The Theory and Practice of Ecotourism in Southern Africa,” Journal of Hospitality Management and Tourism, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2011, pp. 14-21.

- PATA, “Endemic Tourism: A Profitable Industry in a Sustainable Environment,” Kings Cross, 1992.

- WTO, WTTC, Earth Council, “Agenda 21 for the Travel and Tourism Industry: Towards Environmentally Sustainable Development,” WTTC, London, 1995.

- C. Hall, “Historical Antecedents on Sustainable Development: New Labels on Old Bottles?” In: C. M. Hall and A. A. Law, Eds., Sustainable Tourism: A Geographical Perspective, Longman London, 1998, pp. 13-24.

- UNESCAP, “Managing Sustainable Tourism Development: Tourism Review No. 22,” United Nations, New York, 2013. http://www.unescap.org/ttdw/Publications/TPTS_pubs/Toreview_No22_2141.pdf

- M. Lozano-Oyola, F. J. Blancasa, M. González and R. Caballero, “Sustainable Tourism Indicators as Planning Tools in Cultural Destinations,” Journal Ecological Indicators, Vol. 18, 2012, pp. 659-675. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2012.01.014

- International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), “Directory of Afro-Tropical Protected Areas,” IUCN, Gland, 1987.

- S. Metcalfe, “Landscape Conservation and Land Tenure in Zambia: Community Trusts in the Kazungula Heartland,” African Wildlife Foundation, Harare Zimbabwe, 2005.

- V. R. Nyirenda, S. Liwena and H. Kaumba Chaka, “Atlas of the Natonal Parks of Zambia,” New Horizon Printing, Lusaka, 2008.

- Central Statistic Office, “National Accounts Statistical Bulletin,” Republic of Zambia 2010.

- K. T. Taylor and C. T. Banda, “Tourism Development Potential of the Northern Province of Zambia,” American Journal of Tourism Management, Vol. 2, No. 1A, 2013, pp. 10-25.

- Policy Monitoring and Research Centre (PMRC), “Tourism and Wealth Series—Unlocking the Potential of the Tourism Sector to Support Economic Diversification and BroadBased Wealth,” Lusaka, 2013.

- Zambia Wildlife Authority (ZAWA), “Turn-Around Strategy (2011-2016) for the Zambia,” 2011.

- Zambia Tourism Board, “2009 Visitors’ Arrivals Analytical Report,” Ministry of Tourism, Environment and Natural Resources, Government of the Republic of Zambia, 2010.

- P. P. Wong, “Coastal Tourism Development in Southeast Asia: Relevance and Lessons for Coastal Zone Management,” Ocean & Coastal Management, Vol. 38, No. 2, 1998, pp. 89-109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0964-5691(97)00066-5

- B. Hatyoka, “UNWTO Offers Great Benefits to Livingstone,” Times of Zambia, Business Insights: Essentials. Web. 23 October 2013. UNWTO Offers Great Benefits to Livingstone, 28 August 2013.

- The Government of the Republic of Zambia, “Zambia National Report,” The United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20), Government Printer, Lusaka, 2012.

- “Reposition Zambia on Tourism Map,” Times of Zambia 5 December 2012. Business Insights: Essentials. Web. Retrieved on 23 October 2013.

- Zambia Wildlife Authority (ZAWA), “The General Management Plan (GMP) for Mosi-oa-Tunya National Park (MoNP),” 1998.

- Zambia Wildlife Authority, “Five-Year Strategic Plan 2003- 2007,” Volume Implementation Plan, Chilanga, 2002.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), “Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and Its Islands,” IUCN, Gland, 1990.

- E. Chidumayo, F. Lumbwe, K. Mbata and J. Munyandorero, “Review of Baseline Status of Critical Species Habitats in the Mosi oa Tunya National Park,” Department of Biological, University of Zambia, Lusaka, 2003.

- “Tourism Contributes to Environmental Degradation-President Sata,” Lusaka Times, 29 May 2012. Home News: Web. 2012. http://www.lusakatimes.com/2012/05/29/tourism-constributes-environemtal-degradationpresident-sata/

- B. Liu and F. M. Mwanza, “Questionnaire Website, Sustainable Tourism Development in the Case of Livingstone Zambia,” 2012. http://floydmwanza.achievestdzambia.questionpro.com/

- D. Dredge, “Policy Networks and the Local Organisation of Tourism,” Tourism Management, Vol. 27, No. 2, 2006, pp. 269-280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.10.003

- T. Holding, “Environmentally Sustainable Tourism Strategic Plan 2009-2012,” Tourism Victoria Victoria, 2009.

- Government of the Republic of Zambia, “The Tourism Policy for Zambia,” Government Printer, Lusaka, 1999.

- Zambian Environmental Management Agency ZEMA, “Environmental Management Act (EMA),” No. 12. Government Printer, Lusaka, 2011.

- Policy Monitoring and Research Centre (PMRC), “Tourism Series, Tourism: Supporting Sustainable Development, Income and Job Creation, Zambia,” 2013. www.pmrczambia.org.

- Government of the Republic of Zambia (GRZ), “Fifth National Development Plan: Sustained Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction,” Government Printer, Lusaka, 2006.

- Government of the Republic of Zambia (GRZ), “Sixth National Development Plan: Sustained Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction,” Government Printer, Lusaka, 2011, p. 143.

- Grant Thornton Kessle Feinstein, “Study for Development and Promotion of Tourism in Zambia,” 2003.

- Government of the Republic of Zambia, “Formulation of the National Adaptation Programme of Action on Climate Change (Final Report),” Ministry Of Tourism, Environment and Natural Resources, Lusaka, 2007.

- Government of the Republic of Zambia, “The National Environmental Action Plan,” Ministry of Environment & Natural Resources, Lusaka, 1994.

- UNEP, “Biodiversity Planning Support Programme, Guide to Best Practices for Sectoral Integration: Integrating Biodiversity into the Tourism Sector,” United Nations, New York, 2001.

- UNEP, “Report on Industry and Sustainable Tourism for the 7th Session of the CSD Tourism and Environment Protection,” United Nations, New York, 1999.

- UNCED, “Agenda 21,” United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, 1992.

- S. Berrisford, “Revising Spatial Planning Legislation in Zambia: A Case Study,” Urban Forum, Vol. 22, No. 3, 2011, pp. 229-245. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12132-011-9120-2

- Zambia Wildlife Authority-ZAWA, “Final Business Plan,” Government of the Ministry of Tourism, Environment and Natural Resources, Republic of Zambia, 2006.

- Zambia Land Alliance (ZLA), “Land Policy Options for Development and Poverty Reduction Civil Society Views for Pro-Poor Land Policies and Laws in Zambia,” Lusaka, 2008.

- K. Andriotis, “A Framework for the Tourism Planning Process,” In: A. Raj, Ed., Sustainability, Profitability and Successful Tourism, Kanishka Publishers, New Delhι, 2007.

- J. Connell, S. Page and T. A. Bentley, “Towards Sustainable Tourism Planning in New Zealand: Monitoring Local Government Planning under the Resource Management Act,” Tourism Management, Vol. 30, No. 6, 2009, pp. 867-877. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.12.001

- K. Angelevska-Najdeska and G. Rakicevik, “Planning of Sustainable Tourism Development,” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 44, 2012, pp. 210-220. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.022

- K. Kelley, B. Clark, V. Brown and J. Sitzia, “Methodology Matters: Good Practice in the Conduct and Reporting of Survey Research,” International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Vol. 15, No. 3, 2003, pp. 261-266. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzg031

- E. R. Babbie, “Survey Research Methods,” Wadsworth, Belmont, 1990.

- J. E. Bartlett II, J. W. Kotrlik and C. C. Higgins, “Organizational Research: Determining Appropriate Sample Size in Survey Research,” Information Technology, Learning, and Performance Journal, Vol. 19, No. 1, 2001, pp. 43- 50. http://www.osra.org/itlpj/bartlettkotrlikhiggins.pdf.

- A. Attia, “Planning for Sustainable Tourism Development: An Investigation into Implementing Tourism Policy in the Nwc of Egypt,” Thesis Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Development Planning Unit, The Bartlett School Of Architecture and Planning University College London, University Of London, London, 1999.

- E. G. Helmy, “Towards Sustainable Tourism Development Planning: The Case of Egypt,” A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Doctor of Philosophy, Bournemouth University, Bournemouth, 1999.

- D. Dierckx, “How to Estimate Your Population and Survey Sample Size,” 2013. http://www.checkmarket.com/2013/02/how-to-estimate-your-population-and-survey-sample-size/0.

- “The Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP),” Ministry of Finance and National Planning, Government of the Republic of Zambia, 2002.

- Grant Thornton Associates Limited, “Audit of Zambia Wildlife Authority’s (ZAWA’s) Current Capabilities and Development of Project Proposals for Institutional Capacity Development over a Five Year Period (2004-2008),” Lusaka, 2004.

- Government of the Republic of Zambia, “Visitors Arrivals Analyticl Report,” Produced By: Ministry of Tourism, Environment and Natural, Lusaka, 2009.

- World Bank, “Zambia-Support to Economic Expansion and Diversification (SEED): Tourism,” Republic of Zambia Ministry of Tourism, Environment and Natural Resources Securing the Environment for Economic Development (SEED) NW, Washington D.C., 2001. http://www.worldbank.org/infoshop

- Government of the Republic of Zambia, “Mosi-oa-Tunya National Park General Management Plan,” ZAWA, Lusaka, 2000.

- GEF-UNDP-Anchor Environment Consultants, “2001-2006 Economic Analysis and Feasibility Study for Financing Zamibia’s Protected Areas,” GEF-UNDP-Government of Zambia, 2001.

- European Development Fund (EDF), “National Parks and Wildlife Service Project: Draft Master Plan,” Transtec, Milan, 1998.

- C. K. Chunga, “Integration of Sustainable Development in Zambia’s. National Development Plans,” Lessons Learnt &. Recommendations, National Planning Department, Ministry of Finance, 2012.

- D. L. Edgell, M. D. Allen, G. Smith and J. R. Swanson, “Tourism Policy and Planning: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow,” Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, 2008.

- N. Blaikie, “Designing Social Research, An Introduction to Qualitative Research,” Blackwell, Oxford, 2000.

- P. A. DeGeorges and B. K. Reilly, “Sustainability, the Realities of Community Based Natural Resource Management and Biodiversity Conservation in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Economic Growth and Sustainable Wildlife Management, Vol. 1, No. 3, 2009, pp. 734-788. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/su1030734

- R. Dodds, “Sustainable Tourism: A Hope or a Necessity? The case of Tofino, British Columbia,” Canada Journal of Sustainable Development, Vol. 5, No. 5, 2012, pp. 54-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v5n5p54

- A. J. Dougill and M. S. Reed, “Framework for Community-Based Rangeland Degradation Assessment for the Kalahari, Botswana,” RGS-IBG Annual Conference DARG Session on Sustainable Resource Use: Critical Issues in Developing Areas, The Royal Geographical Society, Kensington Gore, 2003, p. 23.

- L. Dwyer, D. Edwards, N. Mistilis, C. Roman, N. Scott and C. Cooper, “Megatrends Underpinning Tourism to 2020: Analysis Of Key Drivers For Change,” CRC for Sustainable Tourism Pty Ltd., Gold Coast, 2008.