Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.07 No.12(2016), Article ID:69585,9 pages

10.4236/jmp.2016.712129

Max Planck Half Quanta as a Natural Explanation for Ordinary and Dark Energy of the Cosmos

Mohamed S. El Naschie

Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, University of Alexandria, Alexandria, Egypt

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 25 July 2016; accepted 5 August 2016; published 8 August 2016

ABSTRACT

The work gives a natural explanation for the ordinary and dark energy density of the cosmos based on conventional quantum mechanical considerations which dates back as far as the early days of the quantum theory and specifically the work of Max Planck who seems to be the first to propose the possibility of a half quanta corresponding to the ground state, i.e. the energy zero point of the vacuum. Combining these old insights with the relatively new results of Hardy’s quantum entanglement and Witten’s topological quantum field theory as well as the fractal version of M-theory, we find a remarkably simple general theory for dark energy and the Casimir effect.

Keywords:

Half Quanta, Dark Energy, Hardy’s Entanglement, Casimir Energy, Topological Quantum Field, Witten’s Theory, Pointless Geometry, Non-Commutative Geometry, Fractal Spacetime, Dark Matter, tHooft Renormalization, E-Infinity Theory, Cantor Sets

1. Introduction

The true nature and origin of dividing energy into two main categories namely ordinary energy which we are able to measure and dark energy which should be there but could not be found or measured in any direct way is one, if not the most puzzling questions of modern science [1] - [6] . In a large number of papers, this question was answered and we think satisfactorily solved by the Author and his associates using mainly advanced mathematics and novel theories about spacetime [7] - [14] . However, and in all fairness to the readers as well as to ourselves, it seems that in the heat of the battle of resolving the mystery of dark energy which came upon all of us as a sudden shock, we seem to have overlooked more conventional elements which may have helped us and others in understanding the main problems within a more conventional framework.

The present work sprang out of such a realization and our final result and explanation of Casimir energy [15] - [17] , ordinary energy and dark energy [18] - [20] is basically a synthesis of an old well known proposal by Max Planck [21] [22] , conventional quantum mechanics [23] , Witten’s topological quantum field theory and M-theories [24] - [27] and last but not least, Hardy’s marvellous result of his gedanken experiment on quantum entanglement [28] [29] . How this is actually done will be shown in what follows. We should also add that we divided the references in the present paper into two parts where Refs. [1] - [76] are the main readings while Refs. [77] - [119] are additional readings which we think deepen and enhance understanding of the subject.

2. Max Planck Half Quanta

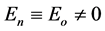

We know very well, at least since J. von Neumann’s pointless continuous geometry [30] [31] and A. Connes’ noncommutative geometry [32] [33] that the definition of a point in classical geometry is totally inadequate on both the philosophical and the pure mathematical level [34] [35] . Thus apart of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, the statement that energy could be zero within a theory based entirely on probability like quantum mechanics cannot be right [23] . Luckily we all know the quantization recipe in quantum mechanics whether found algebraically or using any other method leads to the following famous energy levels equation [23]

(1)

(1)

where  is the Planck reduced constant and w is the frequency. In the above formula n can take only integer values, namely 1, 2, 3, ∙∙∙ because there can be no half

is the Planck reduced constant and w is the frequency. In the above formula n can take only integer values, namely 1, 2, 3, ∙∙∙ because there can be no half  in quantum mechanics since a photon is an elementary particle, in fact the most fundamental elementary messenger particle of them all and

in quantum mechanics since a photon is an elementary particle, in fact the most fundamental elementary messenger particle of them all and  has the same physical meaning as a photon [23] . The more surprizing it must be for the uninitiated to see that even when we have no photon at all, meaning when n = 0, then

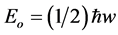

has the same physical meaning as a photon [23] . The more surprizing it must be for the uninitiated to see that even when we have no photon at all, meaning when n = 0, then , i.e. is not zero but a most recognized value given by [23]

, i.e. is not zero but a most recognized value given by [23]

(2)

(2)

The innocent conclusion of the above half quanta is that our postulate gained mainly from experiments that quanta are indivisible cannot be as straight forward as one could naively have thought and who knows, it may open the door to unsuspected connections related to fractional-Hall effects and similar things [119] . Historically speaking this (1/2) which ought to be quite famous because it gives a clear justification for the Casimir effect, goes back to the pioneering efforts of Max Planck to make sense out of his own discovery of the quantization of energy [21] - [23] . In the present work we hope that the reader will also see in the same way that this half is the first step on the road to understand ordinary energy and dark energy [15] - [20] .

3. Hardy’s Amazing Quantum Entanglement Result

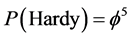

As far as the present Author is concerned there are few modern results in quantum physics that can rival Hardy’s magnificent gedanken experiment regarding the maximal quantum entanglement probability for two quantum particles [28] [29] . The exact answer is found by Hardy using Dirac’s formalism to be [29] .

(3)

(3)

where  in full agreement with experiments [4] - [6] . The implications and ramifications of this exact result for physics and quantum cosmology are tremendous and are amply documented by the hundreds of papers published in the last ten years on this subject by many authors all over the world [2] - [6] . In the next section we will see how

in full agreement with experiments [4] - [6] . The implications and ramifications of this exact result for physics and quantum cosmology are tremendous and are amply documented by the hundreds of papers published in the last ten years on this subject by many authors all over the world [2] - [6] . In the next section we will see how  could be interpreted as a dimensionless, topological Planck constant and how it relates to the zero point energy.

could be interpreted as a dimensionless, topological Planck constant and how it relates to the zero point energy.

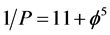

4. The Topological Quantum Field Theory and the Fractal Version of Witten’s M-Theory

Quantum field theory is primarily concerned with investigating the topological invariants of a theory and is the result of pioneering efforts of Schwartz, Attaya, Donaldson and Witten [24] - [26] [36] . It is not possible to overestimate the importance of the work done on this subject. It is equally impossible that the work of the present Author could have seen the light without the work of L. Hardy and Witten’s work, particularly his M-theory as well as his five D-branes in eleven dimensional spacetime model [37] . In fact looking at our own work in the last ten years it appears as if it was a realization of Koester’s sleep-waking hypothesis [38] where our mind was working almost subconsciously at night and consciously during the day on finding hidden connections and links between Witten’s theory, hardy’s result and our own efforts to formulate an exact non-classical spacetime theory guided by Ord-Nottale’s fractal spacetime theory [9] - [13] . At the end it becomes evident that  may be seen as a topological Planck energy while the inverse

may be seen as a topological Planck energy while the inverse  is a topological cosmic distance also playing the role of the dimensionality of the fractal counterpart of Witten’s M-theory as developed by the present Author [27] . We discuss all of that in the next section.

is a topological cosmic distance also playing the role of the dimensionality of the fractal counterpart of Witten’s M-theory as developed by the present Author [27] . We discuss all of that in the next section.

5. The Unifying Power of a Bird’s Eye Topological View

We all have a pretty reasonable understanding and intuitive feel for what a topological dimension means. However what exactly is a Hausdorff dimension [39] ? In nonlinear dynamics the word fractal dimension is used to mean more or less the same as the Hausdorff dimension [39] . Consequently we may see the Hausdorff-fractal dimension not as a normal dimension but as a measure for the irregularity of a fractal shape, its ruggedness or smoothness. This understanding of the Hausdorff dimension brings into it the meaning of entropy which measures the degree of disorder in a system [5] [54] . Proceeding in the same direction it is reasonable to associate the Hausdorff dimension via entropy with energy which is not a stretch [40] . Remembering that our random triadic Cantor set used to model space and time had a Hausdorff dimension equal  as per a theorem due to American mathematicians Mauldin and Williams [7] [41] and remembering also that the result

as per a theorem due to American mathematicians Mauldin and Williams [7] [41] and remembering also that the result  was found using this “Cantorian” theory, then due to what we said earlier on

was found using this “Cantorian” theory, then due to what we said earlier on  could be seen not only as a probability but also as energy, albeit a “topological” energy [7] [14] [42] . Our reasoning is based on the following: First quantum entanglement may be loosely likened to a force acting instantly at a distance and second the probability of finding a point in a Cantor set was fixed not combinatorically because we have infinitely many points, nor geometrically because we have a zero measure [43] but topologically because the Hausdorff dimension is a finite positive value equal

could be seen not only as a probability but also as energy, albeit a “topological” energy [7] [14] [42] . Our reasoning is based on the following: First quantum entanglement may be loosely likened to a force acting instantly at a distance and second the probability of finding a point in a Cantor set was fixed not combinatorically because we have infinitely many points, nor geometrically because we have a zero measure [43] but topologically because the Hausdorff dimension is a finite positive value equal  so that we may write:

so that we may write:

where the length of the unit interval within which the random Cantor set lives is unity. That way we see that

which is what we find in our classical world where we are dealing with almost infinitely many particles and that is why in classical mechanics we do not have measurable entanglement of any kind. From the preceding discussion we see clearly that we could replace

6. From Planck’s Half Quantum to Dark Energy via Ordinary and Casimir Energy

Let us now synthesize and fuse together the preceding result and discussion into a single coherent unity. We start with stating the final result. This is first that the vacuum zero point energy is found from replacing

Second this energy is clearly the cause behind the Casimir effect which is observed via a change of the boundary condition created by the two uncharged but conducting Casimir plates brought at nano distance of each other [15] - [17] [22] . Third, since the boundary condition is the crucial element in the Casimir effect experiment, it follows that at the hyperbolic horizon of our universe we have a one sided boundary condition akin to a one sided Möbius strip but in higher dimensions [65] converting the “local” Casimir effect “energy” into a global dark energy “effect” pushing the boundary of the holographic boundary of the universe and causing the observed accelerated expansion of the cosmos [58] - [62] . Seen that way we may rewrite

This clearly means that Eo is in this case equivalent to the ordinary energy density of the cosmos E(O):

Consequently it follows that the dark energy density is simply [1] - [3] [66]

Comparing these results with the actual cosmic measurements of WMAP, Planck and type 1a supernova [50] - [57] we find that they are in excellent agreement as well as being identical to the result obtained previously using many different methods and models [1] - [6] .

7. Deriving Einstein’s E = mc2 from Quantum Mechanics and Planck’s Half Quanta

The result that

This is twice the dimension of the fractal version of Witten’s M-theory. Proceeding this way one finds [27]

The second possibility is far more straight forward and is nothing more than adding Eo = E(O) and E(D) together and finding that [27] [35] [39]

Either way we see that E = mc2 consists of two quasi quantum components well hidden inside the deceptively simple Einstein’s beauty E = mc2 [119] . We could touch upon trisecting E = mc2 not only into two parts E(O) and E(D) but into three parts making a distinction between dark matter energy E(DM) and pure dark energy D(DE) where

while

In the case of writing E in three parts, we cannot escape the coupling term

where

This coupling could be taken to be approximately

exactly as should be.

8. Conclusion

We gave a derivation for the ordinary energy density and the dark energy density of the universe starting from and based upon conventional and generally accepted quantum mechanical principles. In particular we relied upon a fact introduced probably for the first time by Max Planck, which shows that even in the absence of any real photon, completely empty spacetime has a non-zero energy. From there we went on to show that using this half quanta of Planck which is in the meantime part of most text books on quantum mechanics, we can explain not only the Casimir effect but could also explain the division of energy into ordinary measurable energy as well as dark energy which we cannot measure directly. Thus unlike our previous publications, we did not need to invoke new advanced mathematics nor really any new concepts beyond what one is taught in an advanced course or two in a good university undergraduate program in physics.

Cite this paper

Mohamed S. El Naschie, (2016) Max Planck Half Quanta as a Natural Explanation for Ordinary and Dark Energy of the Cosmos. Journal of Modern Physics,07,1420-1428. doi: 10.4236/jmp.2016.712129

References

- 1. El Naschie, M.S. (2013) Journal of Quantum Information Science, 3, 23-26.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jqis.2013.31006 - 2. El Naschie, M.S. (2013) Journal of Modern Physics, 4, 591-596.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2013.45084 - 3. El Naschie, M.S. (2013) International Journal of Modern Nonlinear Theory & Application, 2, 43-54.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ijmnta.2013.21005 - 4. El Naschie, M.S. (2014) Journal of Quantum Information Science, 4, 83-91.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jqis.2014.42008 - 5. Marek-Crnjac, L., El Naschie, M.S. and He, J.H. (2013) International Journal of Modern Nonlinear Theory and Application, 2, 78-88.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ijmnta.2013.21A010 - 6. Marek-Crnjac, L. and El Naschie, M.S. (2013) Journal of Modern Physics, 4, 31-38.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2013.411A1005 - 7. El Naschie, M.S. (2004) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 19, 209-236.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0960-0779(03)00278-9 - 8. El Naschie, M.S. (2005) International Journal of Nonlinear Sciences and Numerical Simulation, 6, 95-98.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/IJNSNS.2005.6.2.95 - 9. Ord, G.N. (1983) Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General, 16.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0305-4470/16/9/012 - 10. Ord, G.N. (1996) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 7, 821-843.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0960-0779(95)00100-X - 11. McKeon, D.G.C. and Ord, G.N. (1992) Physical Review Letters, 69.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.69.3 - 12. Nottale, L. (1998) Fractal Spacetime and Microphysics. Towards a Theory of Scale Relativity. World Scientific, Singapore.

- 13. Nottale, L. (1989) International Journal of Modern Physics A, 4, 5047.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S0217751X89002156 - 14. El Naschie, M.S. (2004) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 22, 495-511.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2004.02.028 - 15. Plunien, G., Muller, B. and Greiner, W. (1986) Physics Reports, 134, 87-193.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0370-1573(86)90020-7 - 16. Bordag, M., Mohideen, U. and Mostepanenko, V.M. (2001) Physics Reports, 353, 1-205.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0370-1573(01)00015-1 - 17. Milton, K.A. (2001) The Casimir Effect: Physical Manifestations of Zero-Point Energy. World Scientific Publishing, Singapore.

- 18. Marek-Crnjac, L. (2009) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 41, 2697-2705.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2008.10.007 - 19. Helal, M., Marek-Crnjac, L. and He, J.-H. (2013) Open Journal of Microphysics, 3, 141-145.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojm.2013.34020 - 20. Marek-Crnjac, L. and He, J.-H. (2013) International Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 3, 464-471.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ijaa.2013.34053 - 21. Mehra, J. and Rechenberg, H. (1999) Foundations of Physics, 29, 91-132.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1018869221019 - 22. El Naschie, M.S. (2007) International Journal of Nonlinear Sciences and Numerical Simulation, 8, 195-198.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/IJNSNS.2007.8.2.195 - 23. Giffiths, D.J. (2005) Introduction to Quantum Mechanics. 2nd Edition, Pearson Education International, Prentice Hall, London.

- 24. Witten, E. (1988) Communications in Mathematical Physics, 117, 353-386.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01223371 - 25. Atiyah, M.F. (1988) Publications Mathématiques de l’IHéS, 68, 175-186.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02698547 - 26. Schwarz, A. (2000) Topological Quantum Field Theories. arXiv preprint hepth/0011260

- 27. El Naschie, M.S. (2016) Journal of Astronomy & Astrophysics, 6, 135-144.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ijaa.2016.62011 - 28. El Naschie, M.S. (2011) Journal of Quantum Information Science, 1, 50-53.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jqis.2011.12007 - 29. Hardy, L. (1993) Physics Review Letters, 71, 1665-1668.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.71.1665 - 30. Von Neumann, J. (1960) Continuous Geometry. Vol. 25, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- 31. Von Neumann, J. (1981) Continuous Geometries with a Transition Probability. Volume 34, Number 252, American Mathematical Society, Providence.

- 32. Connes, A. (2000) Noncommutative Geometry. In: Alon, N., Bourgain, J., Connes, A., Gromov, M. and Milman, V., Eds., Visions in Mathematics, Birkhäuser, Basel, 481-559.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-0346-0425-3_3 - 33. Connes, A. (2008) Noncommutative Geometry, Quantum Fields and Motives. Vol. 55, American Mathematical Society, Colloquium Publications, Providence.

- 34. El Naschie, M.S. (2016) Advances in Pure Mathematics, 6, 446-454.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/apm.2016.66032 - 35. El Naschie, M.S. (2016) Journal of Modern Physics, 7, 729-736.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2016.78069 - 36. Seiberg, M. and Witten, E. (1999) Journal of High Energy Physics, 09, 032.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1126-6708/1999/09/032 - 37. El Naschie, M.S. (2008) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 38, 1349-1354.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2008.07.002 - 38. Koestler, A. (1968) The Sleep Walkers. Penguin Books, London.

- 39. El Naschie, M.S. (2016) International Journal of Astronomy & Astrophysics, 6, 56-81.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ijaa.2016.61005 - 40. El Naschie, M.S., Olsen, S., He, J.H., Nada, S., Marek-Crnjac, L. and Helal, A. (2012) International Journal of Modern Nonlinear Theory and Application, 1, 84-92.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ijmnta.2012.13012 - 41. El Naschie, M.S. (2006) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 30, 579-605.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2006.03.030 - 42. El Naschie, M.S. (2006) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 27, 297-330.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2005.04.116 - 43. He, J.-H. (2014) International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 53, 3698-3718.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10773-014-2123-8 - 44. El Naschie, M.S. (2013) International Journal of As-tronomy & Astrophysics, 3, 205-211.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ijaa.2013.33024 - 45. El Naschie, M.S. (2013) Journal of Quantum Information Science, 3, 57-77.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jqis.2013.32011 - 46. El Naschie, M.S. (2013) International Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 3, 483-493.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ijaa.2013.34056 - 47. El Naschie, M.S. and Marek-Crnjac, L. (2012) International Journal of Modern Nonlinear Theory and Applications, 1, 118-124.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ijmnta.2012.14018 - 48. El Naschie, M.S. and Helal, A. (2013) International Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 3, 318-343.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ijaa.2013.33037 - 49. El Naschie, M.S. (2013) Journal of Modern Physics, 4, 757-760.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2013.46103 - 50. El Naschie, M.S. (2013) Journal of Modern Physics, 4, 354-356.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2013.43049 - 51. El Naschie, M.S. (2013) Journal of Modern Physics, 4, 1417-1428.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2013.410170 - 52. El Naschie, M.S. (2013) Open Journal of Microphysics, 3, 64-70.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojm.2013.33012 - 53. El Naschie, M.S. (2013) Journal of Quantum Information Science, 3, 121-126.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jqis.2013.34016 - 54. El Naschie, M.S. (2013) International Journal of Modern Nonlinear Theory & Applications, 2, 107-121.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ijmnta.2013.22014 - 55. El Naschie, M.S. (2014) Journal Modern Physics and Applications, 2, 1-7.

- 56. El Naschie, M.S. (2015) International Journal of High Energy Physics, 2, 13-21.

http://dx.doi.org/10.11648/j.ijhep.20150201.12 - 57. El Naschie, M.S. (2014) American Journal of Astronomy & Astrophysics, 2, 72-77.

http://dx.doi.org/10.11648/j.ajaa.20140206.13 - 58. El Naschie, M.S. (1992) Physics-Like Mathematics in Four Dimensions—Implication for Classical and Quantum Mechanics. Computational and Applied Mechanics II, Differential Equations, Elsevier Publisher, North Holland, 15-23. (Selected and Revised Papers from the IMACS 13th World Congress, Edited by Ames, W.F. and Van der Houwen, P.J., Dublin, July 1991)

- 59. El Naschie, M.S. (2016) Journal of Quantum Information Science, 6, 57-61.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jqis.2016.62007 - 60. El Naschie, M.S. (2016) Einstein-Rosen bridge (ER), Journal of Quantum Information Science, 6, 1-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jqis.2016.61001 - 61. El Naschie, M.S. (2016) Natural Science, 8, 152-159.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ns.2016.83018 - 62. El Naschie, M.S. (2016) World Journal of Condensed Matter Physics, 6, 63-67.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/wjcmp.2016.62009 - 63. El Naschie, M.S. (2006) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 30, 656-663.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2006.04.043 - 64. El Naschie, M.S. (2007) International Journal of Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, 8, 11-20.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/IJNSNS.2007.8.1.11 - 65. El Naschie, M.S. (2015) World Journal of Nano Science and Engineering, 5, 49-56.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/wjnse.2015.52007 - 66. Susskind, L. and Friedman, A. (2014) Quantum Mechanics—The Theoretical Minimum. Allen Lane-Penguin Books, London.

- 67. Penrose, R. (2004) The Road to Reality. J. Cape, London.

- 68. El Naschie, M.S. (2014) Journal of Quantum Information Science, 4, 284-291.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jqis.2014.44023 - 69. El Naschie, M.S. (2006) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 30, 636-641.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2006.04.044 - 70. El Naschie, M.S. (2006) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 30, 622-628.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2006.04.042 - 71. El Naschie, M.S. (2007) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 32, 911-915.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2006.08.014 - 72. El Naschie, M.S. (2006) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 30, 1025-1033.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2006.05.088 - 73. El Naschie, M.S. (2006) International Journal Nonlinear Science& Numerical Simulation, 7, 407-409.

- 74. El Naschie, M.S. (2006) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 29, 816-822.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2006.01.013 - 75. El Naschie, M.S. (2008) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 35, 202-211.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2007.05.006 - 76. El Naschie, M.S. (2007) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 32, 468-470.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2006.08.011 - 77. El Naschie, M.S. (2007) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 32, 927-936.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2006.08.017

El Naschie, M.S. (2006) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 29, 845-853.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2006.01.073 - 78. El Naschie, M.S. (2006) International Journal of Nonlinear Science & Numerical Simulation, 7, 129-132.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/IJNSNS.2006.7.2.129 - 79. El Naschie, M.S. (2016) Quantum Matter, 5, 1-4.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1166/qm.2016.1247 - 80. El Naschie, M.S. (2016) Journal of Modern Physics, 17, 156-161.

- 81. Marek-Crnjac, L. (2003) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 15, 611-618.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0960-0779(02)00174-1 - 82. Marek-Crnjac, L. (2004) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 20, 669-682.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2003.10.013 - 83. He, J.-H., Marek-Crnjac, L., Helal, M.A., Nada, S.I. and Rössler, O.E. (2011) Nonlinear Science Letters B, 1, 45-50.

- 84. Marek-Crnjac, L. (2003) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 18, 125-133.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0960-0779(02)00587-8 - 85. El Naschie, M.S., Marek-Crnjac, L. (2013) International Journal of Modern Nonlinear Theory and Application, 1, 118-124.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ijmnta.2012.14018 - 86. El Naschie, M.S. (2006) International Journal of Nonlinear Sciences and Numerical Simulations, 7, 477-481.

- 87. El Naschie, M.S. (1997) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 8, 753-759.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0960-0779(96)00139-7 - 88. El Naschie, M.S. (1997) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 8, 1865-1872.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0960-0779(97)00039-8 - 89. He, J.-H. (2006) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 28, 285-289.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2005.08.001 - 90. He, J.-H., Xu, L., Zhang, L.-N. and Wu, X.-H. (2007) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 33, 5-13.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2006.10.048 - 91. He, J.-H., Ren, Z.F., Fan, J. and Xu, L. (2009) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 41, 1839-1841.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2008.07.035 - 92. He, J.-H. (2006) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 30, 506-511.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2005.11.033 - 93. El Naschie, M.S. and He, J.-H. (2012) Fractal Spacetime, Non-Commutative Geometry in High Energy Physics, 2, 41-49.

- 94. He, J.-H. (2005) International Journal Nonlinear Science& Numerical Simulation, 6, 343-346.

- 95. Nottale, L. (1996) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 7, 877-938.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0960-0779(96)00002-1 - 96. Nottale, L. (1997) Astronomy and Astrophysics, 327, 867-889.

- 97. Nottale, L. (1992) International Journal of Modern Physics A, 7, 4899-4936.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S0217751X92002222 - 98. Nottale, L. (1999) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 10, 459-468.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0960-0779(98)00195-7 - 99. Alexandrov, M., Schwarz, A. and Zabronsky, O. (1997) Journal of Modern Physics A, 12, 1405-1430.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S0217751X97001031 - 100. Witten, E. (1989) Communications in Mathematical Physics, 121, 351-399.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01217730 - 101. Baez, J.C. and Dolan, J. (1995) Journal of Mathematical Physics, 36, 6073-6105.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.531236 - 102. Crane, L. and Frenkel, I.B. (1994) Journal of Mathematical Physics, 35, 5136-5154.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.530746 - 103. Lapidus, M.L. and van Frankenhuysen, M. (2000) Fractal Geometry and Number Theory: Complex dimensions of Fractal Strings and Zeros of Zeta Functions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-5314-3 - 104. Connes, A., Douglas, M.R. and Schwarz, A. (1998) Journal of High Energy Physics, 02, 003.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1126-6708/1998/02/003 - 105. Varilly, J.C. and Gracia-Bondia, J.M. (1993) Journal of Geometry and Physics, 12, 223-301.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0393-0440(93)90038-G - 106. Connes, A. (1995) Journal of Mathematical Physics, 36, 6194-6231.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.531241 - 107. Chamseddine, A.H. and Connes, A. (1996) Physical Review Letters, 77, 4868-4871.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.4868 - 108. Birkhoff, G. and Von Neumann, J. (1936) Annals of Mathematics, 37, 823-843.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1968621 - 109. Von Neumann, J. (2012) The Computer and the Brain. 3rd Edition, Yale University Press, New Haven.

- 110. Von Neumann, J. (1936) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 22, 101-108.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.22.2.101 - 111. Von Neumann, J. (1955) Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- 112. El Naschie, M.S. (2015) American Journal of Nano Research and Applications, 3, 33-40.

- 113. El Naschie, M.S. (2015) Natural Science, 7, 287-298.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ns.2015.76032 - 114. El Naschie, M.S. (2015) World Journal of Nano Science & Engineering, 5, 26-33.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/wjnse.2015.51004 - 115. El Naschie, M.S. (2015) Natural Science, 7, 210-225.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ns.2015.74024 - 116. El Naschie, M.S. (2014) Journal of Modern Physics, 5, 743-750.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2014.59084 - 117. El Naschie, M.S. (2016) American Journal of Computational Mathematics, 6, 185-199.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajcm.2016.63020 - 118. Babchin, A.J. and El Naschie, M.S. (2015) World Journal of Condensed Matter Physics, 7, 581-598.

- 119. Da Cruz, W. (2004) Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 23, 373-378.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2004.05.031