Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.06 No.11(2015), Article ID:59588,10 pages

10.4236/jmp.2015.611151

Scalable Cavity Quantum Electrodynamics System for Quantum Computing

Mohammad Hasan Aram, Sina Khorasani

Department of Electrical Engineering, Sharif University of Technology, Tehran, Iran

Email: khorasani@sina.sharif.edu

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 18 August 2015; accepted 12 September 2015; published 15 September 2015

ABSTRACT

We introduce a new scalable cavity quantum electrodynamics platform which can be used for quantum computing. This system is composed of coupled photonic crystal (PC) cavities which their modes lie on a Dirac cone in the whole super crystal band structure. Quantum information is stored in quantum dots that are positioned inside the cavities. We show if there is just one quantum dot in the system, energy as photon is exchanged between the quantum dot and the Dirac modes sinusoidally. Meanwhile the quantum dot becomes entangled with Dirac modes. If we insert more quantum dots into the system, they also become entangled with each other.

Keywords:

Cavity Quantum Electro Dynamics, Photonic Crystal, Dirac Cone, Quantum Computing

1. Introduction

After about seventy years from Purcell’s famous paper [1] which established cavity quantum electrodynamics (CQED), this field is still active and interesting for many researchers [2] . This is primarily due to a concept called coupling constant. It is a criterion to measure the strength of atom-cavity interaction. Atom interacts with cavity through exchange of energy quanta or photon. The stronger this interaction is, the faster the exchange of photon occurs. So we can say coupling constant measures the rate of photon exchange between atom and cavity.

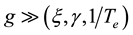

But why has this simple concept made this field so attractive? The answer is behind its role in quantum information and computation theory. We know quantum computers are powerful in solving some kind of pro- blems. This is due to an inherent parallel processing power in them that originates from quantum physics. In order to use this capability of quantum physics we have to create entangled states between qubits of the quantum computer. In other words, if we save information on qubits which are not entangled, our computer has no advantage over its classical counterparts. By increasing the rate of photon exchange between atom and cavity, we can create entangled state of them. To measure this rate we need a criterion, that is, we have to compare it with an amount to determine if it is high or not. There are three criteria as follows:

1) Presence duration of atom inside the cavity. In some cavity quantum electrodynamics systems atoms stay inside the cavity for a short period of time. In these systems atoms enter the cavity from an aperture and after interaction exit from the other side. If energy exchange occurs in a period of time longer than atom presence duration (Te), then the coupling constant is small and we say the coupling is weak.

2) Photon decay rate. We know there is no lossless cavity. This loss has many causes among them we can mention leakage through cavity walls and cavity walls absorption. If we show photon annihilation rate by ξ, photon exchange rate must be larger than ξ to have strong coupling.

3) Atom spontaneous emission rate. Another factor to be considered for measuring coupling strength is the time interval that atom can maintain photon before radiating it to vacuum modes outside the cavity via spontaneous emission. Spontaneous emission rate is shown by γ. So to have strong coupling we need photon exchange rate to be much larger than γ.

The photon exchange rate between atom and cavity (coupling constant) is measured by Rabi frequency (g). So the last paragraph can be summarized as: If , then the atom-cavity system is in the strong coupling regime. Otherwise the coupling is weak. In many systems like the one analyzed here, quantum dots are used instead of real atoms or ions. Since quantum dots are always inside the cavity, we can assume

, then the atom-cavity system is in the strong coupling regime. Otherwise the coupling is weak. In many systems like the one analyzed here, quantum dots are used instead of real atoms or ions. Since quantum dots are always inside the cavity, we can assume . Hence in these systems we just need to compare g with γ and ξ to determine the coupling strength. Usually photon decay rate is greater than atom spontaneous emission rate [3] , so it is usually sufficient to compare g with ξ.

. Hence in these systems we just need to compare g with γ and ξ to determine the coupling strength. Usually photon decay rate is greater than atom spontaneous emission rate [3] , so it is usually sufficient to compare g with ξ.

In strong coupling regime different phenomena occur. Among them is vacuum Rabi splitting in which upper atomic energy level splits into two close levels which result in two peaks in spontaneous emission spectrum of the atom that had only one otherwise [4] .

Many reports of strong coupling attainment have been presented till now [5] - [11] . But in recent years some groups are trying to go beyond strong coupling and reach ultra-strong coupling regime [12] - [14] . In this regime Rabi frequency is comparable with photon frequency. It is predicted atom behaves chaotically in this regime [15] .

CQED has many applications, but its capability to be used as a platform for quantum computing is much more attractive. Up to now different systems have been proposed to be used for quantum computing [16] - [21] . All of these systems have some limitations and shortcomings. One of their serous limitations is their hard scalability. In most of these systems we can have only a few numbers of qubits. Here we propose a new system which does not have this limitation and can be used as an alternative for the old CQED systems in quantum computation. This system is composed of coupled photonic crystal resonators array (CPCRA) where each resonator is a cavity that can contain a quantum dot. The cavities are arranged such that a Dirac cone appears in the super crystal band structure.

In the remaining we first show how we can obtain Dirac cone by choosing appropriate position for the cavities, next we obtain Hamiltonian of the system that makes study of atom evolution due to interaction with Dirac cone modes possible.

2. Dirac Cone Modes

In one of our previous works we showed how we can design a photonic crystal that has Dirac point in its transverse electric (TE) band structure [22] . In this section we review it briefly. At first we designed a two dimensional (2D) crystal with Dirac point. We adopted the crystal lattice from graphene which has a honey comb lattice and Dirac point has already been observed in its band structure. So we chose a triangular lattice of air holes in a dielectric for the basis crystal and replaced Carbon atoms by cavities. Different patterns for cavities positions were tested to finally reach the pattern shown in Figure 1. We assumed the crystal to be made of Silicon with relative permittivity of . Next we generalized our design to a photonic crystal slab. We used different methods to show Dirac point in its band structure but here we just explain tight-binding because we need it in subsequent sections.

. Next we generalized our design to a photonic crystal slab. We used different methods to show Dirac point in its band structure but here we just explain tight-binding because we need it in subsequent sections.

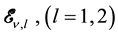

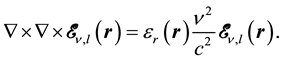

To utilize tight-binding method we should first obtain modes of a single cavity. Each of the designed cavities has two orthogonal degenerate modes that are shown in Figure 2. If we represent the electric fields of these modes at resonant frequency , by

, by , then according to Maxwell’s first and second equations we can write

, then according to Maxwell’s first and second equations we can write

Figure 1. Photonic crystal slab with Dirac point in band structure. Crystal dielectric is Silicon with .

.

Figure 2. Field distribution of (a)  of first mode; (b)

of first mode; (b)  of first mode; (c)

of first mode; (c)  of first mode; (d)

of first mode; (d)  of second mode; (e)

of second mode; (e)  of second mode; (f)

of second mode; (f)  of second mode for a single cavity.

of second mode for a single cavity.

(1)

(1)

In this equation  is the relative permittivity profile of a single cavity and c is the speed of light in vacuum. Since eigen modes of the cavity are orthogonal we have

is the relative permittivity profile of a single cavity and c is the speed of light in vacuum. Since eigen modes of the cavity are orthogonal we have

where we have normalized the modes. According to Bloch theorem, electric field in the super crystal can be written as

where

for the whole crystal field, where

Replacing

where

Using the approximations

which is valid for confined cavity fields and doing some simplification we finally obtain the following eigenvalue problem.

The two bands which are shown in Figure 3 construct the Dirac cone and are obtained by solving this problem.

3. System Hamiltonian

Now we position a quantum dot inside one of the super crystal cavities. To find its behavior due to interaction with Dirac modes we have to determine the system Hamiltonian. We assume the quantum dot is at position

where

Figure 3. The two bands of PC slab which construct the Dirac cone. They are calcu- lated using tight-binding method.

is the electron Hamiltonian in the absence of the field,

is the interaction of electron momentum with the field, and

is the interaction of different field modes through coupling with electron. Because of

We can write

where

In this relation

where

To write

Using the commutator relation

between atom Hamiltonian and position operator,

where

Now we should write magnetic vector potential operator based on photon annihilation,

where the sum is over all the cavity modes,

In most of quantum optics texts,

where

Note that here we have obviously more modes than in the case of a single cavity which has only two modes. Therefore

where

is the Rabi frequency. In Equation (12) we have used the fact that atomic and photonic operators commute with each other, that is

In rotating wave approximation (RWA),

Finally Hamiltonian of the whole system becomes

where

is the Hamiltonian of the electromagnetic field and

Our system, in its simplest form, consists of a quantum dot with two energy eigen states inside one of the

where the sums are over all the confined Dirac modes, that is the modes which fall below the light cone of the super crystal. In this equation p = 1 and p = 2 denote the lower and upper parts of the cone respectively. We have neglected zero point energy of the field which only shifts all the system energy levels by a constant value. We have also assumed the interaction with other modes of the crystal is not very different from interaction with vacuum and have omitted it in this equation.

In the remaining, without losing the problem generality, we set

the second. Hence considering Equation (3), we conclude

4. Atom Evolution

For simplicity we assume there is initially no photon in the system and the atom is in a superposition state of its ground and exited states. So we can write the initial state of the system as

where

The state of the system in times

where the effect of

has been included in the state via exponential terms. By inserting the system ket state from Equation (18) and the system Hamiltonian from Equation (15) into Schrödinger equation

we reach

By equating the coefficients of similar kets at both sides, we obtain the following system of equations.

The first equation indicates

By replacing

To calculate

where

In this equation

Figure 4. Variation of (a)

and

(23)

where we have used

relations. We have also set

(24)

Using Equations (23) and (24) we get

which results in

with

If we want to obtain

Figure 5.

and two time intervals. It is seen

5. Conclusion

We proposed a new platform to be used for quantum computing. We first showed we could create Dirac cone in the band structure of a PC using coupled cavities inside a triangular lattice. Next we studied the evolution of a quantum dot positioned at the center of one of the cavities due to interaction with Dirac cone modes. We observed the quantum dot exchanged photon with Dirac modes sinusoidally and became entangled with them.

Cite this paper

Mohammad HasanAram,SinaKhorasani, (2015) Scalable Cavity Quantum Electrodynamics System for Quantum Computing. Journal of Modern Physics,06,1467-1477. doi: 10.4236/jmp.2015.611151

References

- 1. Purcell, E.M., Torrey, H.C. and Pound, R.V. (1946) Physical Review, 69, 681.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.69.37 - 2. Walther, H., Varcoe, B.T.H., Englert, B. and Becker, T. (2006) Reports on Progress in Physics, 69, 1325-1382.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0034-4885/69/5/R02 - 3. Mabuchi, H. and Doherty, A.C. (2002) Science, 298, 1372-1377.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1078446 - 4. Raizen, M.G., Thompson, R.J., Brecha, R.J., Kimble, H.J. and Carmichael, H.J. (1989) Physical Review Letters, 63, 240.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.63.240 - 5. Ohta, R., Ota, Y., Nomura, M., Kumagai, N., Ishida, S., Iwamoto, S. and Arakawa, Y. (2011) Applied Physics Letters, 98, Article ID: 173104.

- 6. Thon, S.M., Rakher, M.T., Kim, H., Gudat, J., Irvine, W.T.M., Petroff, P.M. and Bouwmeester, D. (2009) Applied Physics Letters, 94, Article ID: 111115.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.3103885 - 7. Reithmaier, J.P., Sek, G., Löffler, A., Hofmann, C., Kuhn, S., Reitzenstein, S., Keldysh, L.V., Kulakovskii, V.D., Reinecke, T.L. and Forchel, A. (2004) Nature, 432, 197-200.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature02969 - 8. Lev, B., Srinivasan, K., Barclay, P., Painter, O. and Mabuchi, H. (2004) Nanotechnology, 15, S556.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/15/10/010 - 9. Buck, J.R. and Kimble, H.J. (2003) Physical Review A, 67, Article ID: 033806.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.67.033806 - 10. Aoki, T., Dayan, B., Wilcut, E., Bowen, W.P., Parkins, A.S., Kippenberg, T.J., Vahala, K.J. and Kimble, H.J. (2006) Nature, 443, 671-674.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature05147 - 11. Hennessy, K., Badolato, A., Winger, M., Gerace, D., Atature, M., Gulde, S., Falt, S., Hu, E.L. and Imamoglu, A. (2007) Nature, 445, 896-899.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature05586 - 12. Casanova, J., Romero, G., Lizuain, I., García-Ripoll, J.J. and Solano, E. (2010) Physical Review Letters, 105, Article ID: 263603.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.263603 - 13. Liberato, S.D. (2014) Physical Review Letters, 112, Article ID: 016401.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.016401 - 14. Günter, G., Anappara, A.A., Hees, J., Sell, A., Biasiol, G., Sorba, L., Liberato, S.D., Ciuti, C., Tredicucci, A., Leitenstorfer, A. and Huber, R. (2009) Nature, 458, 178-181.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature07838 - 15. Shahraki, M.A., Khorasani, S. and Aram, M.H. (2014) Applied Physics A, 115, 595-603.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00339-013-8025-4 - 16. Ladd, T.D., Jelezko, F., Laflamme, R., Nakamura, Y., Monroe, C. and O’Brien, J.L. (2010) Nature, 464, 45-53.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature08812 - 17. Vandersypen, L.M.K., Steffen, M., Sherwood, M.H., Yannoni, C.S., Breyta, G. and Chuang, I.L. (2000) Applied Physics Letters, 76, 646-648.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.125846 - 18. Vandersypen, L.M.K., Steffen, M., Breyta, G., Yannoni, C.S., Sherwood, M.H. and Chuang, I.L. (2001) Nature, 414, 883-887.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.125846 - 19. Schoelkopf, R.J. and Girvin, S.M. (2008) Nature, 451, 664-669.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/451664a - 20. Houck, A.A., Türeci, H.E. and Koch, J. (2012) Nature Physics, 8, 292-299.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nphys2251 - 21. DiCarlo, L., Chow, J.M., Gambetta, J.M., Bishop, L.S., Johnson, B.R., Schuster, D.I., Majer, J., Blais, A., Frunzio, L., Girvin, S.M. and Schoelkopf, R.J. (2009) Nature, 460, 240-244.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature08121 - 22. Aram, M.H., Mohajeri, R. and Khorasani, S. (2013) Applied Physics A, 115, 581-587.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00339-013-8023-6 - 23. Schleich, W.P. (2001) Quantum Optics in Phase Space. Wiley-VCH, Berlin.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/3527602976 - 24. Andreani, L.C., Panzarini, G. and Gérard, J.-M. (1999) Physical Review B, 60, Article ID: 13276.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.60.13276 - 25. Nielsen, M.A. and Chuang, I.L. (2010) Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press, New York.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511976667