Advances in Bioscience and Biotechnology

Vol.4 No.6(2013), Article ID:33532,9 pages DOI:10.4236/abb.2013.46094

Preliminary study of binary protein adsorption system and potential bioseparation under homogeneous field of shear in airlift biocontactor

![]()

1Department of Chemical Engineering, Ryerson University, Toronto, Canada

2New Brunswick Department of Agriculture & Aquaculture, Potato Development Center, Wicklow, Ireland

*Corresponding Author: ydahman@ryerson.ca

Copyright © 2013 Yaser Dahman, Kithsiri E. Jayasuriya. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 1 March 2013; revised 25 April 2013; accepted 14 May 2013

Keywords: Protein Purification; Protein Adsorption; Hindrance in Adsorption; Conformation; Binary Protein Adsorption

ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the bioseparation of binary protein mixtures using polystyrene based anion exchange resin. Adsorption experiments were conducted in batch mode using draft-tube internally recirculate dair lift biocontactor in comparison with the conventional shake flask batch adsorption equilibrium experiments. Binary protein mixtures contained bovine serum albumin (BSA) and bovine haemoglobin (BHb) at different initial fractions. Results from single solute adsorption experiments in biocontactor showed that both proteins were equally adsorbed onto the resin with equilibrium reached in an equal time period. This represents similar affinities towards the negatively charged resin surface, although BSA was expected to adsorb through specific forces. Adsorption results showed that BSA has hindered the BHb adsorption in the biocontactor, although adsorption of both proteins was equally hindered in the shake flasks adsorption experiments. Moreover, adsorption of BHb was inhibited up to 29% in the presence of BSA compared to the adsorption of BHb from a solution containing single solute of BHb at the same initial concentration. Similarly, the presence of BHb has hindered the adsorption of BSA by 59%. Adsorptions of both BSA and BHb from binary solution when each formed 75% initial fraction while the other protein formed the remaining 25% were relatively low with equilibrium reached in shorter time. Moreover, considerable amount of proteins remained in the solution, which demonstrates that multilayer adsorption most likely didn’t occur at the relatively small protein concentrations used in the present study. In general, the higher adsorption of BHb can also be related to the compressibility of its molecules which allowed for higher adsorption capacity. The homogeneous and lower shear environment in the airlift biocontactor compared to the other conventional batch adsorption in shake flask reduced the compressibility of BHb that caused higher BSA adsorption from binary solutions of BSA and BHb, which allowed for better bioseparation of both proteins.

1. INTRODUCTION

Bioseparation of proteins has been investigated over many years using different techniques such as adsorption, covalent binding, and entrapment within polymer gels [1]. The main objective behind improving bioseparation of proteins is to allow their recycling and thus facilitating their handling and recovery in terms of industrial and environmental benefits. At present, proteins recovery from large volumes of industrial broths and effluent purification systems has become essential with the broadening of industrial avenues and increasing use of functional proteins. Simultaneously, special interests in protein bioseparation have also increased due to the fact that commercialization of therapeutic proteins derived from industrial biotechnology is more advanced than that of gene biotechnology [2-4]. Immobilization of proteins also has been utilized in immunological testing systems, biochemical sensors, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [1].

Protein adsorption on solid surfaces is of great interest in many technologies and industrial processes [2]. Protein adsorption generally occurs through a complex mechanism that involves many steps in which, initially, the protein molecules undergo conformation and orientation changes [2,3,5,6]. In order to further understand parameters affecting protein adsorption onto solid surface, polystyrene (PS) based resins have widely been used as a model substrate to study and analyze the mechanism of interactions between proteins and resin surface and the adsorption was believed to be mediated by non-specific hydrophobic interactions [7-9]. It is important to understand that adsorption and bioprocessing of cells and proteins in addition to other biological materials may encounter problems due to their delicate nature. This is interpreted by the shear effect (i.e., “mechanical forces” or “hydrodynamic forces”), which are important in several industries that include processing of proteins in solution. This includes manufacturing of enzymes and in the fermentation, purification, formulation, in addition to recovery of protein drug products [10,11]. Such damages to proteins can cause changes to their secondary and/or tertiary structures through unfolding, or disruption of their quaternary structure of a multi-subunit protein. This can also lead to promoting protein aggregation to give soluble or insoluble aggregates [12-14].

Another important component that affects adsorption is the type of biocontactors, which conventional adsorption techniques using packed beds separation systems have widely been investigated and applied. This technique has several drawbacks since it requires the feed stream to be free of any particulates to avoid any blocking of the adsorbent beds. Such congestions would result in pressure drops and requiring a back flush to remove the clogged particles which require filtration, centrifugation and/or solids settling steps [14]. Therefore, a bioseparation technique that does not require a prior removal of particulate matter would be considered to be vitally important. Conventional fluidized bed technology can overcome this major problem with the relatively large voidage between the fluidized adsorbents that prevents any blockage of the bed [14-16]. Furthermore, the higher fluid mechanical shear in conventional fixed bed adsorption techniques can cause damage to proteins [10-14]. Along the same line of interest, airlift or gas-lift bioreactors were proven to be important in emerging fluidizing technology, where industrially important microorganisms are used as catalysts. These bioreactors exploit hydrostatic pressure differences on fluid circulation. This class of bioreactors consists of a liquid pool divided into two distinct zones one of which is purged with air or gas. The contents of the bioreactor circulate by a gas-lift action due to different bulk densities between gassed and un-gassed zones. Fluidizing agent causes the fluid motion after being pumped into the inner draft tube of the bioreactor [17,18]. The overall directionality of internal flow generates a homogeneous field of shear, which has been proven to be essential for better mass transfer during adsorption [18,19]. Because of their advanced hydrodynamics, mass transfer characteristics and uniformity in the shear environment, airlift bioreactors (or biocontactors) are increasingly being applied in medical, pharmaceutical, dyes and fragrances industries, biotechnology and in multiphase chemical reactions [19- 21].

Under the light of all these facts that influence adsorption process, the present work investigates protein adsorption using internally recirculated draft-tube airlift fluidized biocontactor in comparison with the conventional shake flask adsorption. Furthermore, a known model system that includes PS ion exchange resin as the adsorbent and a binary model protein system that consists of BSA and BHb as the adsorbates in single and binary solute adsorption experiments were adopted. The main objective behind this work is to investigate the interaction forces and steric hindrance effect of different proteins in multi-solute adsorption system, and to analyze the effect of the uniform and low shear adsorption environment of the biocontactors for achieving better bioseparation.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Material Specifications

Cross-linked PS based anion exchange resin (DOWEX®) was purchased from Aldrich. This resin is styrene and divinyl benzene copolymer with chloromethyl trimethy amine functionality in chloride form. Functionality was calculated to be 3.89 mmol chlorine g−1 resin, and the particles have an average diameter of ~0.3 - 1.2 mm and a density of ~1.1 g·L−1). The resin was washed with DDI water and dried overnight in a vacuum desiccator prior to the adsorption trials. Bovine serum albumin (BSA; fraction V, 67 k·Da, Equivalent radius = 3.61 nm) and bovine haemoglobin (BHb; 68 k·Da, Equivalent radius = 3.1 nm) were purchased from Sigma Chemicals and were used in single or binary forms in the protein adsorption experiments. The 0.01 M phosphate buffer saline (PBS) of pH 7 was purchased from Sigma Immuno Chemicals and was used as received.

2.2. Adsorption Isotherm Experiments

Batch adsorption trials were carried out in the airlift fluidized biocontactor using 6.25 g of the resin in 100 ml of solution containing either a single or binary mixture of BSA and BHb prepared from stock solutions (0.25 g·L−1 = 3.7 mmol·L−1) in the PBS buffer (pH 7). It was assumed that protein-protein interactions are negligible at these low concentrations [10]. PBS buffer solution concentration was maintained at 0.01 M, which is equivalent to solution ionic strength in the range of 0.01 - 0.02 M. It was shown that, this range of ionic strength has negligible effect on adsorption [5]. The temperature was maintained at 25˚C while, the air flow rate was controlled by calibrated rotameter (Cole-Parmer).

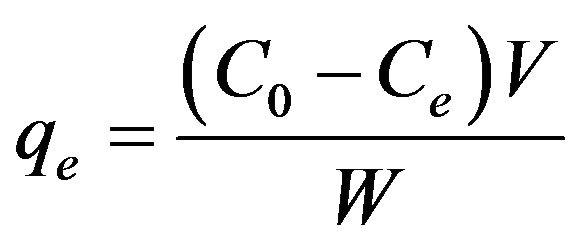

Experiments were conducted in the airlift biocontactor from solutions containing either single protein or binary mixtures of BSA and BHb at different initial compositions (fractions from 0-100% by weight with the increment of 25%) and total initial concentration (C0) = 0.25 g·L−1 at 25˚C ± 1˚C. Binary solutions were prepared with different initial fractions by weight since both proteins have similar molecular weights. All adsorption experiments were allowed to reach equilibrium in 24 hours, although equilibrium was reached in 4 hours in all adsorption experiments conducted. Samples of 1 mL were periodically taken for monitoring protein concentrations with time, all of which were returned back immediately into the solution in order to maintain a constant total volume. Samples were filtered (cellulose nitrate, lowprotein-adsorbing, 0.2 mm, Micro Filtration Systems, USA) and proteins were quantified by UV-Vis spectroscopy (Varian Cary 50-Bio, Varian Inc.), based on calibration curves of same proteins. BHb concentration after adsorption was determined at 406 nm, while BSA concentration after adsorption was determined at 280 nm, after subtracting the contribution of BHb as determined from the concentration detected at 406 nm. The total amount of protein adsorbed per unit weight of polymer (qe; g protein g−1 polymer) was calculated from Equation (1).

(1)

(1)

where, V is the buffer volume (L), C0 is the initial concentration (g·L−1), Ce is the concentration at equilibrium (g·L−1), and W is the weight of the adsorbent (g).

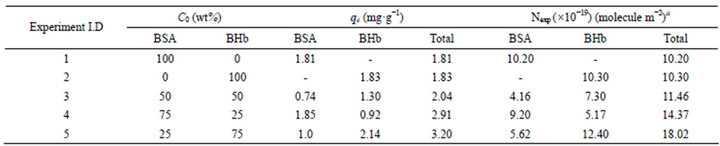

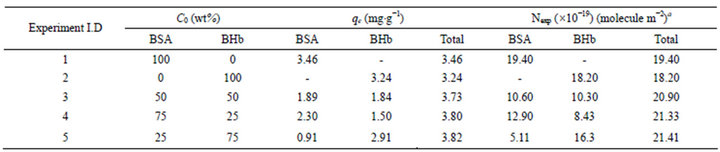

Adsorption experiments were similarly conducted in shaking flasks containing binary protein mixtures in PBS at the different initial compositions. Conventional shake flask adsorption experiments were used as reference to stimulate adsorption environments with higher mechanical shear. The proteins adsorbed were quantified using the Equation (1). Tables 1 and 2 list conditions and re sults of different adsorption experiments from single andbinary proteins solutions in airlift biocontactor and in shake flasks with total protein C0 = 0.25 g·L−1. All reported adsorption results were the average of replicates, with an average error of 7%.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

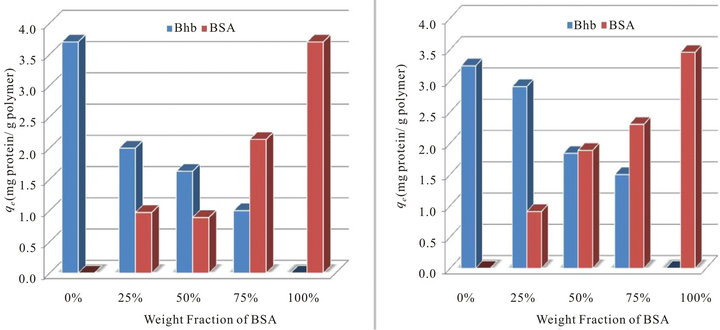

Figures 1(a) and (b) summarize respectively the total amounts of proteins adsorbed in the airlift biocontactor and in shake flasks from solutions containing binary mixtures of BSA and BHb at different initial fractions (0% - 100% with the increment of 25%). Examining these figures indicate that the total amount of both BSA and BHb adsorbed in the biocontactor from solutions containing each individually (i.e., at 100% initial fractions) were practically similar ( ~1.81 and 1.83 mg protein g−1 resin respectively; Experiments 1 and 2 in Table 1). This demonstrates similar affinity of both proteins towards adsorption onto the PS resin in the biocontactor. Similar results were obtained for the individual protein adsorption in shake flask, with higher adsorption capacities obtained compared to the biocontactor (~3.46 and 3.24 mg protein g−1 resin respectively; Experiments 1 and 2 in Table 2).

Surprisingly, the amounts of proteins that were adsorbed from binary solutions containing 50% initial fractions and with initial concentration of each protein similar to that in the individual experiments were equal in the shake flasks (Figure 1(a)), while more BHb was adsorbed in the biocontactor than BSA (Figure 1(a)). Generally, proteins adsorb onto anionic exchange resin due to electrostatic interactions of amino acid side chains and the surface charges of the resin. The net charge of a protein molecule depends on the isoelectric point (pI) of the protein and on the solution pH. In the present study, BHb molecules with pI of 7.0 have neutral net charge at pH 7 [22,23]. In contrast, BSA with pI of 4.5 is expected to have a net negative charge at pH 7, due to their ampholytic (zwitterionic) properties [24,25]. Based on that, BSA is expected to adsorb onto the PS resin through specific interactions and achieve higher selectivity in bio-

Table 1. Total BSA and BHb adsorbed onto the PS ion exchange resin at equilibrium from single and binary proteins adsorption experiments (fraction of 0% - 100%) in the airlift biocontactor (pH 7.0 and 25˚C).

Table 2. Total BSA and BHb adsorbed onto the PS ion exchange resin at equilibrium from single and binary proteins adsorption experiments(fraction of 0% - 100%) in the shake flasks (pH 7.0 and 25˚C).

(a) (b)

(a) (b)

Figure 1. Total amounts of proteins adsorbed onto PS ion exchange resin (qt; mg protein L−1) from different single and binary solutions containing mixtures of BSA and BHb of weight fractions between 0 - 1 at comparable C0 (pH 7 and 25˚C) (a) in airlift biocontactor; (b) in shake flasks.

separation. However, the similar adsorption capacities of both proteins reflect similar affinities. Based on the literatures, BHb adsorbs through non-specific hydrophobic interactions that reduced the possibility of achieving highly efficient bioseparation in a pre-designed process. Revilla et al. [22] reported a maximum adsorption capacity of 2.35 mg BSA nm−2 at pH 4.5, while Shirahama et al. [8] reported an adsorption capacity of 2.80 mg BHb nm−2 at pH 7, showing an indication that in the event of low pH, the adsorption of BSA can be increased over the adsorption of other proteins present in the same solution.

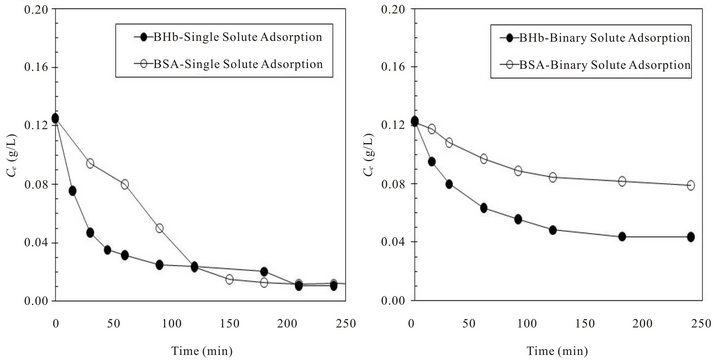

Figures 2(a) and (b) show respectively the concentration changes in adsorption experiments (Ct; g protein L−1) from single and binary protein solutions (with 50:50 initial weight fraction of BSA and BHb); C0 of all proteins was 0.125 g·L−1 in all cases.

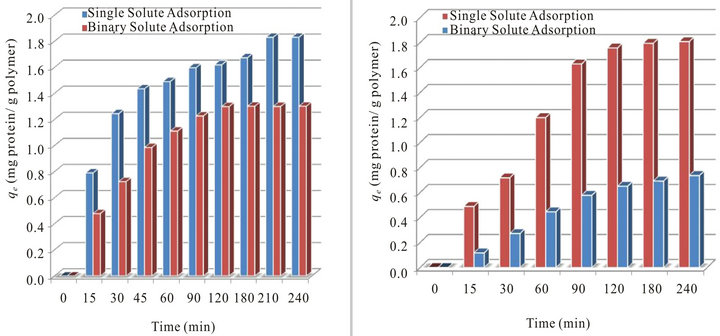

Examining Figures 2(a) and (b) shows that concentration of BHb in the solution decreased rapidly at the early stages of adsorption more than that of BSA from single solute adsorption experiments. Adsorption from binary solute shows more decrease in BHb until reaching equilibrium than BSA. These results shows the higher affinity of the neutrally charged BHb molecules (pI = 7.1) towards PS resin surface. Moreover, the lower adsorption of BSA can be explained by the higher self interaction forced among their molecules due to the repulsion forces imposed by the negatively charged BSA (pI = 4.7) compared to the lower electrostatic repulsion forces expected amount the neutrally charged BHb protein molecules. Figures 3(a) and (b) show respectively the changes occurred in the concentration of both proteins in the adsorbed phase (qe; mg protein g−1 resin) in adsorption experiments from single and binary proteins adsorption experiments (initial fraction of 50:50 by weight). Results presented in Figure 3 were obtained from the adsorption equilibrium results in Figure 2.

As shown in Figure 3(a), the total amount of BHb adsorbed in the single solute adsorption experiment was 1.83 mg BHb g−1of polymer. Moreover, the total BHb adsorbed in the BHb binary solutions at 50:50 was 1.3 mg BHb g−1 of polymer. This clearly reveals that the presence of BSA in the solution has affected the adsorption of BHb. This steric hindrance effect can be explained by the possible molecular interactions in the so

(a) (b)

(a) (b)

Figure 2. Change in BSA and BHb solution concentrations with time from single and binary proteins adsorption experiments at comparable C0 (pH 7 and 25˚C): (a) single protein adsorption with C0 (BSA and BHb) = 0.125 g·L−1 (b) binary solute adsorption with equal protein initial fractions of 50:50 with total C0 = 0.25 g·L−1.

lution and on the resin surface, which all seems to exist even at the low solution concentration levels considered in the present work [7-9]. Analyzing results in Figure 3(a) shows that the adsorption of BHb was inhibited up to 29% in the presence of BSA in the solution at the same initial concentration compared to the adsorption of BHb from a solution containing single solute of BHb at the same C0 of 0.125 g·L−1. Similarly, the total amount of BSA adsorbed in the single protein adsorption was 1.81 mg BSA g−1of resin, while the amount of BSA adsorbed from binary solution at the presence of BHb was 0.74 mg BSA g−1 of resin as seen in Figure 3(b). The presence of BHb in the same solution at the same initial concentration has hindered the adsorption of BSA by 59%.

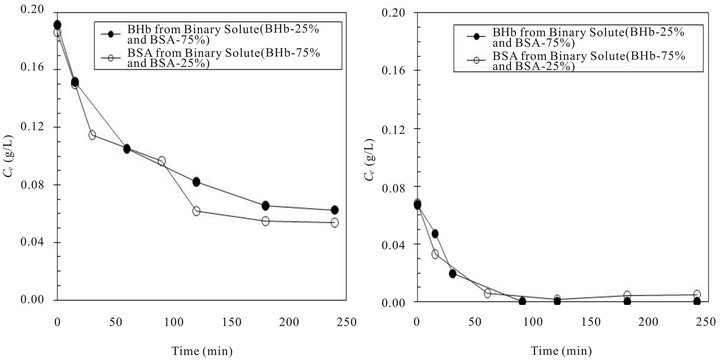

The higher hindrance observed on the adsorption of BSA in the presence of BHb than that of BHb in the presence of BSA can initially be explained by the higher affinity of BHb towards the PS surface. However, this didn’t lead to higher adsorption capacity in the single solute adsorption experiments (Figure 1). The repulsion forces between the charged BSA molecules might also have caused self-steric hindrance for adsorption. Another important factor might be related to the highly compressible BHb molecules that cause higher adsorption capacities versus the ellipsoidally shaped BSA molecules (specific hydrodynamic dimensions of ~14 × 4 × 4 nm) that might cause unstable adsorption onto solid surfaces [15]. In order to examine the effect of these factors, cross comparison of the concentration changes in adsorption experiments from two different binary adsorption experiments that had BSA and BHb at 75:25 and 25:75 initial weight fractions were essential. The purpose is to analyze the effect of the presence of each protein at lower initial content on the adsorption of the other protein at higher content. Figure 4(a) shows the changes in concentration of both proteins when formed 75% initial fraction (C0 of each protein = 0.1875 g·L−1), while Figure 4(b) when both proteins formed 25% initial fraction (C0 of each protein = 0.0625 g·L−1).

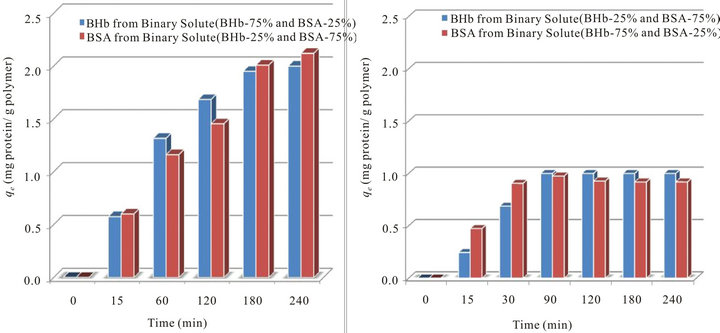

Adsorption profile in Figure 4(a) shows lower adsorption capacities with equilibrium reached in 3 hours of adsorption for each protein of higher initial fractions. Moreover, considerable amount of proteins remained in the solution after reaching equilibrium (i.e., concentration of both proteins at equilibrium was ~0.05 g·L−1). This demonstrates that multilayer adsorption most likely did not occur in the present investigation and that monolayer adsorption is a reasonable assumption. Comparing adsorption capacities obtained with what was obtained when each protein formed 100% initial fraction, and considering that both proteins had lower initial concentrations, it is clear that the presence of another protein at lower initial fraction enhanced adsorption for both proteins. However, this effect was more obvious in the presence of BHb. In binary solutions, when each of the competing proteins formed 25% (the other formed 75% by weight; Figure 4(b)), adsorption profiles of both BSA and BHb were almost similar (1.0 mg·g−1 resin and 0.92 mg·g−1 resin for BSA and BHb respectively) and quick reaching the zero concentration in the solution just in less than 1.5 hours. Adsorption profiles are shown in Figures 5(a) and (b).

It is clear from Figure 5 that when BHb formed the higher initial fraction (Experiment 5 in Table 1), higher

(a) (b)

(a) (b)

Figure 3. Comparison of the total amounts of BSA and BHb adsorbed per time onto ps ion exchange resin (qt; mg protein g−1 polymer) from single and binary protein adsorption experiments at initial fractions of 50:50 (Co of BSA or BHb = 0.125 g·L−1, at pH 7.0 and 25˚C): (a)BHb; (b) BSA.

(a) (b)

(a) (b)

Figure 4. Comparison of change in BSA and BHb solution concentrations with time from binary proteins adsorption experiments at initial fractions of 75:25 and 25:75 respectively (total C0 = 0.25 g·L−1, pH 7 and 25˚C): (a) BSA and BHb at initial fraction of 75% (i.e., C0 (BSA or BHb) = 0.1875 g·L−1); (b) BSA and BHb at initial fraction of 25% (i.e., C0 (BSA or BHb) = 0.0625 g·L−1).

amount of BHb was adsorbed (2.14 mg BHb·g−1 resin) compared to Experiment 2 in Table 1 when it formed 100% of the initial fraction (1.83 mg BHb·g−1 resin). However, similar amount of BSA (~1.8 mg BSA g−1 of resin) was adsorbed in the equivalent cases (Experiments 4 and 1 in Table 1). Comparing this to results obtained from Figure 2 (Experiments 1 - 3 in Table 1) reveals that the presence of BSA at higher initial fraction (Experiment 4 in Table 1) surprisingly suppressed the adsorption of BHb.

In previous investigations, several researchers such as Dahman et al. [5] in addition to Kondo and Higashitani

(a) (b)

(a) (b)

Figure 5. Comparison of the total amounts of BSA and BHb adsorbed per time onto ps ion exchange resin (qt; mg protein g−1 polymer) from binary protein adsorption experiments at initial fractions of 75:25 and 25:75 (C0 = 0.25 g L−1, at pH 7.0 and 25˚C): (a) BSA and BHb at initial fraction of 75% (i.e., C0(BSA or BHb) = 0.1875 g·L−1); (b) BSA and BHb at initial fraction of 25% (i.e., C0 (BSA or BHb) = 0.0625 g·L−1).

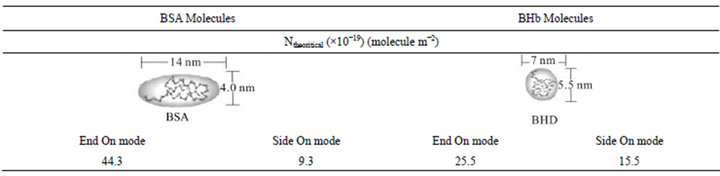

[7] reported the ability of BHb to be compressed since it is a very soft and flexible protein. They observed that the experimental monolayer capacity of adsorbed haemoglobin is higher than the theoretically calculated capacity based on its hydrodynamic dimensions. Experimental monolayer adsorption capacities (Nexp; molecule m−2) were calculated here based on qm values and specific surface areas of the PS resin considering the hydrodynamic dimensions of BSA and BHb (i.e., 14 × 4 × 4 nm and 7 × 5.5 × 5.5 nm, respectively) [5]. Values of Nexp are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 for adsorption experiments in the biocontactor and shake flasks, respectively. Similarly, maximum theoretical surface monolayer adsorption capacity (Ntheo; molecule m−2) were calculated for both proteins based on end-on and side-on orientation modes. Results for Ntheo are summarized in Table 3, while Scheme 1 shows the different possible orientation for the monolayer adsorbed protein molecules.

Results for Nexp of BSA and BHb calculated for the single solute adsorption experiments in shake flasks (Experiments 1 and 2 in Table 2) were between values of Ntheo calculated based on side-on and end-on orientation modes. This demonstrates that adsorbed protein molecules are oriented in combination of end-on and side-on adsorption modes. Comparing these values with the values obtained from single protein adsorption in the biocontactor (Experiments 1 and 2 in Table 1) reveals that both proteins were adsorbed in side-on mode in the biocontractor. Reorientation of adsorbed proteins molecules in shake flasks may explain the higher adsorption capacity compared to the biocontactor. Moreover, under the high shear environment of the shake flask, compressibility of the soft BHb might be able to cause higher monolayer capacity since multilayer adsorption was not evident in this study as discussed above. This explains the higher adsorption capacities of total proteins adsorbed using the shake flask (Table 2) compared to the fluidized biocontactor (Table 1). According to Dickinson [24], high shear forces caused by agitations usually results in less time allowed for adsorbed protein molecules to re-orient over the resin surface. This obviously will result in lower surface area occupied per adsorbed molecule, and will lead to higher adsorption capacity especially for soft proteins. This effect of higher stress did not influence the adsorption of the BSA. This all prove that the lower shear environment in the airlift biocontactor allowed for better separation from solutions containing both BSA and BHb than in the shake flask adsorption.

In general, this study showed that higher BHb adsorption over BSA was observed more in shake flasks than in the airlift biocontactor. This usually is explained based on multilayer adsorption although it was not evident in the present study, in addition to the compressibility of the soft BHb as discussed above. The higher shear environment caused by shaking also results in less time allowed for the adsorbed protein molecules to re-orient to the

Scheme 1. Possible orientations of adsorbed ellipsoidal protein molecules.

Table 3. Maximum theoretical monolayer adsorption capacity of close-packed adsorbed BSA and BHb molecules on the PS resin surface.

side-on mode after adsorption. This obviously resulted in that adsorbed BSA molecules were oriented in combination of end-on and side-on adsorption modes. Meanwhile, such shear environment caused more compression for the soft BHb adsorbed molecules. The lower surface area occupied per adsorbed protein molecules led to higher adsorption capacity in shake flasks. The higher adsorption of BHb was observed in the biocontactor of lower shear when it was at its higher initial fraction, while equal adsorption was obtained for both BSA and BHb at lower initial contents. This hindrance in BSA adsorption in the biocontactor in the presence of higher BHb was explained based on the molecular interaction between the negatively charged molecules. Apparently this resulted in better separation of both proteins in the airlift biocontactor, which was not observed in the shake flask adsorption experiments. This demonstrates potential application of the airlift biocontactor in protein bioseparation exploiting better understanding of the interactions among protein molecular level.

4. CONCLUSIONS

The present study discussed results for the bioseparation of BSA and BHb from binary mixtures using biocontactor and shake flasks in batch adsorption equilibrium modes. Similar amount of both proteins were adsorbed in the biocontactor in single solute adsorption experiments, while adsorption of BSA was higher in shake flasks. Adsorption experiments from binary solution with initial fraction of 50:50 by weight showed that the presence of each protein in the solution inhibited the adsorption of the other protein when compared with the single solute adsorption experiments. The presence of BHb in binary solution of both proteins at similar initial fractions hindered the adsorption of BSA by 59% while adsorption of BHb was inhibited up to 29% when compared to results from single solute adsorption experiments. Apparently, the presence of both proteins caused steric hindrance effect on adsorption probably due to the increasing competition towards the adsorbent surface in addition to the interaction among proteins molecules in the solution. Mainly the negatively charged BSA molecules at pH 7 might have caused self-steric hindrance for adsorption due to the repulsion forces among BSA molecules. Lower adsorption with equilibrium reached in 3 hours was observed for both BSA and BHb when each formed 75% in binary adsorption experiments while the other formed the remaining 25%. Considerable amount of proteins remained in the solution, which proves that multilayer adsorption most likely didn’t occur in the present study. This represents that the higher adsorption capacity of the BHb observed throughout the adsorption experiments can be explained mainly based on the compressed adsorbed molecules in addition to the orientation of the adsorbed molecules.

5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was financially supported by awards from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and the Faculty of Engineering and Architectural Science at Ryerson University in Toronto, Canada.

REFERENCES

- Bickerstaff, G.F. (1997) Immobilization of enzymes and cells. Human Press, Totowa.

- Rapoza, R. and Horbett, T. (1990) The effects of concentration and adsorption time on the elutability of adsorbed proteins in surfactant solutions of varying structures and concentrations. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 136, 480-492. doi:10.1016/0021-9797(90)90395-5

- Van Holde, K.E., Johnson, W.C. and Ho, P.S. (1998) Principles of physical biochemistry. Prentice-Hall Inc., New Jersey.

- Denizli, A. and Piskin, E. (2001) Dye-legend affinity systems. Journal of Biochemical and Biophysical Methods, 49, 391-416. doi:10.1016/S0165-022X(01)00209-3

- Dahman, Y., Puskas, J., Margaritis, A. and Cunningham, M. (2004) Novel thymine-functionalized polystyrenes for applications in biotechnology. 2. Adsorption of Model Proteins. Biomacromolecules, 5, 1412-1421. doi:10.1021/bm034497r

- Kondo, A. and Higashitani, K. (1992) Adsorption of model proteins with wide variation in molecular properties on colloid particles. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 150, 344-351. doi:10.1016/0021-9797(92)90204-Y

- Shirahama, H., Susuki, K. and Suzawa, Y. (1989) Bovine haemoglobin adsorption onto polymer lattices. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 129, 483-490. doi:10.1016/0021-9797(89)90462-1

- Absolom, D., Zingg, W. and Neumann, A. (1997) Protein adsorption to polymer particles: Role of surface properties. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, 21, 161- 171. doi:10.1002/jbm.820210202

- Yoon, J.Y., Park, H.Y., Kim, J.H. and Kim, W.S. (1998) Interpretation of protein adsorption phenomena onto functional microspheres. Journal of Colloids and Surface B, 12, 15-26. doi:10.1016/S0927-7765(98)00045-9

- Ghadge, R.S., Patwardhan, A.W., Sawant, S.B. and Joshi, J.B. (2005) Effect of flow pattern on cellulase deactivation in stirred tank bioreactors. Chemical Engineering Science, 60, 1067-1083. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2004.09.069

- Rathore, N. and Rajan, R.S. (2008) Current perspectives on stability of protein drug products during formulation, fill and finish operations. Biotechnology Progress, 24, 504- 514. doi:10.1021/bp070462h

- Jaspe, J. and Hagen, S.J. (2006) Do protein molecules unfold in a simple shear flow? Biophysical Journal, 91, 3415-3424. doi:10.1529/biophysj.106.089367

- Otero, C., Fernandez-Perez, M. and Perez-Gil, J. (2005) Effects of interactions with micellar interfaces on the activity and structure of different lipolytic isoenzymes from Candida rugosa. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 37, 695-703. doi:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2005.03.023

- Wierenga, P.A., Egmond, M.R., Voragen, A. and de Jongh, H. (2006) The adsorption and unfolding kinetics determines the folding state of proteins at the air-water interface and thereby the equation of state. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 299, 850-857. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2006.03.016

- Postel, C., Abillon, O. and Desbat, B. (2003) Structure and denaturation of adsorbed lysozyme at the air-water interface. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 266, 74- 81. doi:10.1016/S0021-9797(03)00571-X

- Garcia, M., Bonen, J., Ramirez-Vick, M. and Sadaka, A.V. (1999) Bioseparation process science. Blackwell, California.

- Ahuja, S. (2000) Handbook of bioseparations. Academic, California.

- Moo-Young, M. and Chisti, Y. (1989) On the calculation of shear rate and apparent viscosity in airlift and bubble column bioreactors. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 34, 1391-1392. doi:10.1002/bit.260341107

- Chisti, Y. (1989) Airlift bioreactors. Elsevier, New York.

- Chisti, Y., Wenge, F. and Moo-Young, M. (1995) Relationship between riser and downcomer gas hold-up in internal-loop airlift reactors without gas-liquid separators. Chemical Engineering Journal, 57, 7-13.

- Peterson, E. and Margaritis, A. (2001) Hydrodynamic and mass transfer characteristics of three-phase gas-lift bioreactor systems. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, 21, 233-294. doi:10.1080/07388550108984172

- Revilla, J., El-Aissari, A., Carriere, P. and Pichot, C. (1996) Adsorption of bovine serum albumin onto polystyrene latex particles bearing saccharidic moieties. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 180, 405-412. doi:10.1006/jcis.1996.0319

- Causserand, C., Kara, Y. and Aimar, P.J. (2001) Protein fractionation using selective adsorption on clay surface before filtration. Journal of Membrane Science, 186, 165- 181. doi:10.1016/S0376-7388(01)00332-5

- Dickinson, E. (1999) Adsorbed protein layers at fluid interfaces: Interactions, structure and surface rheology. Journal of Colloids and Interfaces B: Biointerfaces, 15, 161-176.

- McMurry, J. (1999) Organic chemistry. 5th Edition, Brooks Cole, California.

NOMENCLATURES

BSA: bovine serum albumin BHb: bovine haemoglobin C0: initial concentration (g·L−1)

Ce: concentration at equilibrium (g·L−1)

Dowex®: Cross-linked polystyrene based anion exchange resin Nexp: experimental monolayer adsorption capacities (molecule m−2)

Ntheo: maximum theoretical surface monolayer adsorption capacity (molecule m−2)

PS: Polystyrene pI: isoelectric point qe: total amount of protein adsorbed per unit weight of polymer (g protein g−1 polymer)

V: buffer volume (L)

W: weight of the adsorbent (g).