Modern Economy

Vol.5 No.6(2014), Article

ID:46912,10

pages

DOI:10.4236/me.2014.56065

Human Potential of Rural Development in Post-Soviet Russia: Risks and Threats

Zemfira I. Kalugina

Institute of Economics and Industrial Engineering, Department of Sociology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Siberian Branch, Novosibirsk, Russia

Email: zima@ieie.nsc.ru

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 9 April 2014; revised 9 May 2014; accepted 19 May 2014

ABSTRACT

This article examines the results of market transformation of the agrarian sector in Russia 1990s- 2000s, as well as social risks of human development. The author defines social risks as possible negative consequences of social policies that represent a threat to human development. Among them author refers to the lack of resources required for the reproduction of human capital; low public spending on health, education and recreational services not compensated for the lack of individual investments in human capital development; excessive social stratification of society, not conducive to economic growth and social development; low share of the middle class as a support and the driving force of innovation development and social progress; lack of an economic base for the expansion of the middle class. By summarizing, the author concludes that the lack of resources for human development makes illusory hopes for breakthrough innovation in the development of the agro-food complex in rural areas.

Keywords:Rural Development, Agricultural Policy, Market Transformation, Social Risks, Human Development

1. Introduction

In the current era of global challenges, there is no alternative to an innovation and knowledge-based development scenario. It implies the development of human potential as a key element of national wealth and a major driving force of economic growth, which is much more important than natural resources or accumulated wealth. This means that an individual is not only viewed as an object of social policy, but also as its actor, who takes a proactive stance with regard to his/her health, education, and professional activities. However, the low standards of living of a large majority of the population prevent from individual investments in health, education, and culture at a level that would be sufficient for developing human potential. In this context, public investment in human capital through the development of health, education, culture, and sports plays an increasingly important role. The task of business is to provide their employees with good working conditions and adequate remuneration for the use of physical and intellectual resources. Particularly these acute problems manifest themselves in the agricultural sector as a result of market transformation.

2. Results of Market Transformation Russia’s Agrarian Sector

The agrarian reforms during the 1990s were intended to radically transform Russia’s agrarian sector. These included a reorganization of collective owned farms (kolkhozes and sovkhozes), land reforms, and support for private sector development in the agrarian economy. The reforms were aimed at increasing social and economic activity amongst the rural population. Labor collectives were given the right to determine how they would be managed and workers had the option to leave their collective farms. Land was divided among agricultural workers and a number of other groups. Land and property shares formed the basis of start-up capital for business development on a cooperative or individual basis.

In the course of this, new forms of management became increasingly institutionalized, resulting in a mixed agrarian economy [1] -[6] . These measures were supposed to foster the competition between goods producers in the agrarian market. The various types of management made it possible to take advantage of both largeand small-scale production, combining the capabilities of large-scale agricultural production and individual entrepreneurial initiative. These radical changes in ownership patterns were assumed to lead to an efficient allocation of land and other means of production. In the future, it will promote the development of private entrepreneurship in agriculture and in services. Administrative restrictions on developing household plots1 were lifted. Relying on the ‘invisible hand’ of the market, the state significantly reduced agricultural subsidies, so that in 1999 agricultural subsidies amounted to only 0.17% of the GDP, as compared with 0.52% in 1995 and 8.8% in 1990 [7] .

While the initial stages of reforms were intended to create the institutional and legal conditions which were believed to be necessary for a fair and effective development of land management, the results were unexpected (for reformers) . This was evident, for example, in the expansion of small-scale production, inefficient allocation of resources, decreasing motivation amongst farm workers, rural poverty, the degradation of social services in rural areas, and the emergence of Institutional traps: the small farm trap, the trap of permanent unprofitability and the trap of lowering wages and poverty amongst the rural population. Institutional trap is, in my opinion, due to the institutional innovations of the stable existence of inefficient behaviors, which in turn support the sustainable existence of inefficiency of public institutions [8] .

Russian reformers’ expectations associated with the invisible hand of the market have failed to materialize. The emergence of numerous institutional traps, due to inconsistent and contradictory reforms has resulted in a number of negative developments in the agricultural sector. Negative effects are in particular reduced overall productivity, a drastic reduction of agricultural output, and, correspondingly, a significant increase in imports of agricultural products. Agricultural production in 1998 reached its lowest level and was 56% from 1990 levels, while the number of unprofitable agricultural enterprises increased from 3% to 88% [9] .

Since 2000, Russia’s agricultural policies were aimed at reducing the institutional traps. In the early 2000s, changes were made to the financial and institutional support given to rural producers, such as improving access to financial loans. The core national project for the development of the agricultural sector consisted of three main areas: an increase in livestock production, the promotion of small-scale farming (household plots and private farms), and realization of the program building affordable housing for rural professionals (doctors, teachers, agronomists, etc.), which are sorely lacking in rural areas [10] . While these measures had a positive impact on the activities of the agricultural sector, they were unable to solve all its problems.

Agricultural policies during this period were aimed at achieving a sustainable development of the agricultural sector and in rural areas more generally. The main aims were: a sustainable socio-economic development in rural areas, an increase in agricultural output, more efficient agricultural production systems, sustainable land use, and improving rural livelihoods. The policies succeeded in terms of increasing agricultural output, reducing the number of unprofitable agricultural enterprises, increasing profitability and reducing the share of non-profit family farms (households) in agricultural production.

In 2002, Russia passed a law allowing the free sale of land. During this period, agricultural businesses were a potentially attractive investment. The state encouraged the arrival of large-scale investors in the agricultural sector and the subsidy system favored large-scale enterprises. In the early 2000s, 1.4% of the largest farms received 22.5% of all subsidies [11] .

State agricultural policy during the 2000s advantaged large-scale agricultural enterprises, making investments into agriculture particularly attractive to large-scale investors. Contrary to what might be expected, this development did not lead to an updating of technologies, techniques and managerial approaches and, ultimately, increased productivity in the agricultural sector. Instead, it resulted in a sharp increase in unemployment, thus contributing to increased economic inequality and social tensions in rural areas. Competition for land, skilled labor and state support increased. Thus, the local modernization gave local economic effect, but caused negative social consequences. The measures were not a holistic approach to agribusiness development and focused insufficiently on the sector’s future development and on attempts to solve problems which reduce the relevance and effectiveness of the measures.

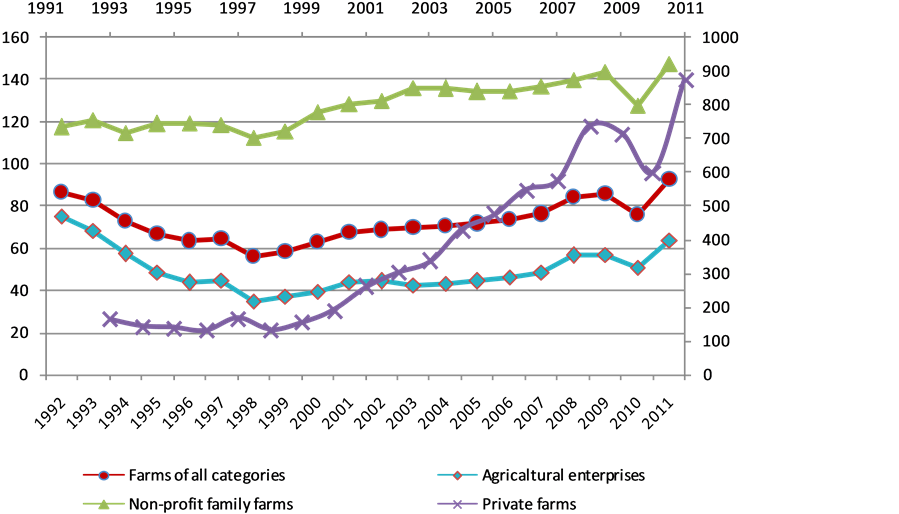

The global financial and economic crisis of 2008/2009 initiated further institutional reforms directed at the agri-food complex. Russia’s grain production increased dynamically. Gross grain output increased from 65.5 million tons to 108.2 million tons between 2000 and 2008, with an average annual growth of 3.8%. This, in turn, made cereals an important export, increasing from 1.3 million tons in 2000 (2% of the gross grain harvest) to 18.2 million tons in 2008 (16.8% gross yield), making Russia the third biggest exporter of cereals after the United States and the European Union [12] . Overall, agricultural output grew 10.8% between 2008 and 2009, which is especially relevant considering the 1.2% decline in other sectors [13] . Dynamics of agricultural production in Russia in 1990-2013 years is presented in Figure 1.

3. Social Risks of Rural Development

Risk Society—it’s essentially a new paradigm is replaced by the concept of community production and distribution of wealth. “In developed countries, the modern world production of wealth is always accompanied by public production risks” [14] . Obvious sense of this statement Ulrich Beck is that as with modernization of the productive forces increase the threat to the survival and human development. In contrast to the dangers caused by natural disasters, social risks are the inevitable product of decision-making. Social risks, in our context are

Figure 1. The volume index of agricultural production by types of farms in 1992-2011 (at constant prices, 1990 = 100—left scale, for private farms 1992 = 100—right scale), % Calculated by [15] .

the probable negative consequences of social policy pursued by that threaten human development. Actors (producers) risk may be policy, businesspersons, social groups. “Consumers”, objects of social risk or risk groups are social groups, communities and individuals who have been affected decisions taken risk subjects. According to Giddens’ concept of the existing institutional environment sets standardized behaviors of individuals and generates so collective risks. In addition, each form of social life in a certain period of time has its own “portfolio” or set of risks [16] .

Try to determine a portfolio of social risks and threats to rural development in post-Soviet Russia. These, in our view, include:

• lack of resources required for the reproduction of human capital in the aggravated crisis;

• low social expenditures state, not compensate for the lack of individual investments in human capital development;

• excessive social stratification of society, is not conducive to economic growth and social development;

• low share of the middle class as a support and the driving force of innovation development and social progress;

• lack of an economic base for the expansion of the middle class.

3.1. Conditions for the Reproduction of Human Potential

According to calculations made by the National Living Standards Center, the minimum consumer budget, which is equal to approximately two living wages (LWs) in monetary terms, allows people to satisfy their minimal nutritional needs and to purchase some nonfood items and fee based services and thus guarantees a minimum level of consumption providing a simple reproduction of human capital. Being sufficient to satisfy the rational physical and intellectual needs of the population, a high-income (by modern standards, average) budget, which is equal to about six and more LWs, secures a developmental pattern of consumption [17] . In other words, consumers’ budgets reflect the consumption patterns of social groups with different levels of material prosperity. The incomes of poor people allow them to make ends meet, but also force them to produce some food and clothing for themselves and widely rely on their work at home. With an income increase, better-off groups of the population tend to reduce their household work, give up own production, and, in a longer term, purchase the required goods and services. The qualitative changes in the consumer behavior of groups with higher incomes are reflected in their quest for better education and healthcare beyond free public services. That is, these groups’ incomes allow them to spend more on education, professional growth, and development [18] .

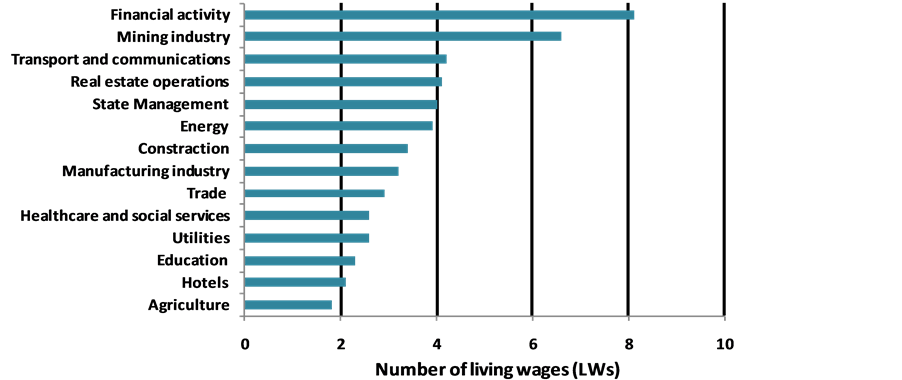

Comparison of wage with a living wage showed that in Russian Federation, in 2011, only employees of the financial sector and mining industries had developmental budgets. The earnings of employees in other sectors provided simple reproduction of human potential. The wages of agricultural workers were below the minimum consumer budget and thus prevented them from restoring their human potential at a very basic level (Figure 2).

In other words, everyone who heals, teaches, feeds, and serves the population does not have sufficient resources to improve their educational level and qualifications or have required levels of rest. Representatives of these social groups are more pressured to find additional sources of income to support their families. The reality is that the majority of doctors and teachers and employees of many other service industries tend to work 150 or 200% of the norm. At the same time, the quality of human capital of both the working population and younger generation depends on the work of these particular professionals.

According to our calculations based on the data obtained from a sample survey of household budgets, in the fourth quarter of 2012, nearly 42% of urban and 65% of rural residents of the Russian Federation had per capita incomes below the minimum consumer budget (13410 rubles)2 and thus could not even restore their human potential because of a lack of required resources. The same ratio for per capita disposable resources was 38% and 59% [19] . This situation is due to the fact that nearly half of total income is concentrated in the fifth (and the wealthiest) group of population, while the same amount of funding is spread among all other groups.

If the private sector is an area of corporate responsibility, the public sector is an area of state responsibility. The state has in its disposal a powerful instrument for income regulation, namely, social policy. Overall, the earnings of only 3% of employees ensured them a growing type of consumption, while the earnings of the absolute majority of employees only allowed them to recover their performance capacity. Agricultural workers, who are always outside the wage scale, did not even have these resources. Despite some positive trends in recent years, the wages of agricultural workers are still below the minimum consumer budget; the latter provides the reproduction of labor force at a recovery level and stands at nearly 53% of the average wage in the entire economy. Over the past ten years the average nominal wage of an employee in the national economy has grown considerably. However, it had no significant impact on the conditions of human potential reproduction as per capita personal income is approximately 0.9 times below the wage level. The negative implications of this situation are clear (Figure 3).

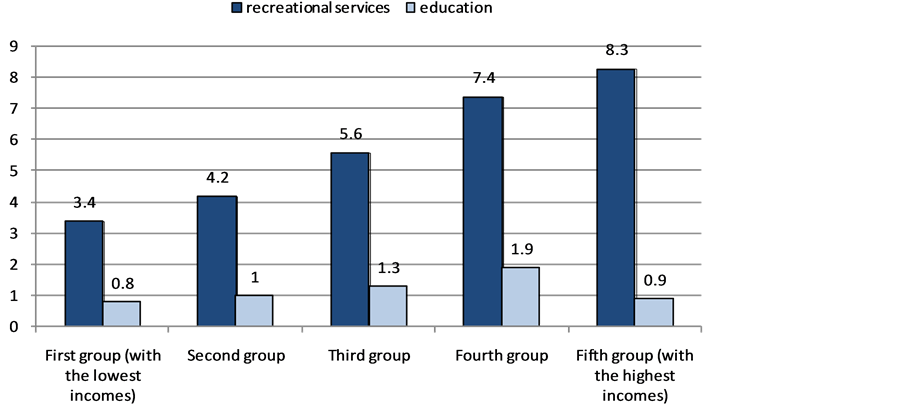

The expenditure structure of the rural population’s consumption is marked with a high share of food spending and a low share of recreation and cultural activities costs (37.7% and 4.4%, respectively, vs. 26.1% and 6.2% in urban areas), which indicates the impoverishment level of the rural population. The spending on education was 0.5% and 1.0%, respectively [19] .

According to the outcome of the national poll “Our Values and Interests Today” (the sixth round), conducted by the Center for Social and Cultural Changes, Institute of Philosophy, Russian Academy of Sciences, the problem of access to high-quality healthcare is associated with long queues, the shortage of professionally qualified doctors, and expensive drugs. It is one of the most acute problems for the Russians. Respectively, 41%, 35%,

Figure 2. Ratio of wages and living wages by economic activity in the Russian Federation, 2011. Calculated on the basis of [20] .

Figure 3. Share of spending on recreational and educational services to 20% income groups of the population, the Russian Federation in 2011, % [20] .

and 23% of respondents highlighted these shortcomings. Across the national contingent, the index of access to education (the difference between the share of positive and negative responses is +100) was 98, meaning that negative responses dominated the poll. This problem particularly affects low-income groups of the population, as well as those who do not hold managerial positions. The index of access to education only exceeded 100 for two top income groups (out of six) and reached 166 for managers [21] . This situation can be explained by the fact that nearly 60 out of 100 students study on a fee basis and this creates unequal starting conditions for young people from different income and social strata. Thus, in Russia income inequality combined with inequality of opportunity. Creating social mobility President Putin considered one of the key tasks of social policy.

Therefore, the conditions of human potential reproduction in rural areas are much worse than these in cities; this factor has an impact on the level of education, income, and life expectancy. So, by the mid 1990s, the differences in the life expectancy of the rural and urban population (64.7 and 64.2 years, respectively) were not significant. By the early 2000s, the average life expectancy of countrymen (57.8 years for men and 71.2 years for women) was much lower than that of urban residents (59.2 years for men and 72.3 years for women). In the mid-2000s, this difference remained unchanged.

The dynamics and level of education among agricultural workers is also affected by negative trends. It is known that educated young people escape the countryside. The majority of regions and agricultural enterprises suffer from a deficit in highly qualified staff. If the aim is to technologically upgrade agricultural production and to develop a social infrastructure, which is the key for the future of the countryside, it is obvious how acute the problem is.

To ensure the expanded reproduction of human potential (at the level of the existing standards) for all types of economic activity, one should at least double the average nominal wage and triple it in the social sector and agriculture. To improve productivity through increased high-tech sector of the economy, and, accordingly, to enhance the segment of highly-paid labor, the state should create institutional conditions that would have forced the domestic and foreign business conduct active investment policy in their enterprises.

However, according to the official forecast, the average annual growth of investment in fixed assets in 2011-2013 will amount to 7%. Projected capital expenditure significantly below the minimum level required not only to implement the strategy of advancing development, but also for simple reproduction of fixed assets. By the end of the forecast period is planned to increase the savings rate to 21.9%, which is below half the current rate of savings in the economy. This indicates a significant under-utilization of investment potential. Even by the end of the forecast period, investment in fixed capital will be almost 20% lower than in 1991, i.e. before the start of the post-Soviet transformation. Accordingly inevitably lag Russia not only from the “golden billion”, but also from a group of rapidly progressive countries “developing” world [22] .

Thus, resource insecurity of human capital reproduction in the agricultural sector makes illusory hopes upgrading agri-food complex, due to the lack of demand for skilled labor and the conditions for human development as the main productive force of society.

3.2. Social Inequality and Development

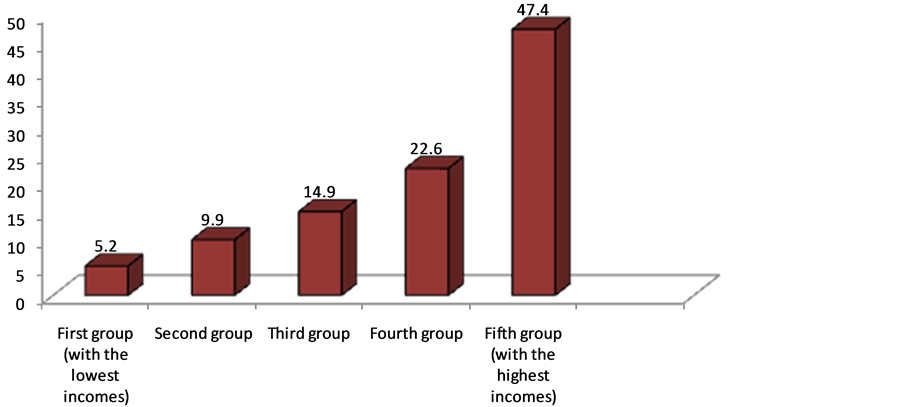

The established remuneration systems in the private and public sectors, as well as the current state policy for income generation and distribution, have resulted in unprecedented social stratification. Over years, the gap between the rich and poor in Russia has only been growing: the Gini coefficient (income concentration index) increased from 0.387 in 1995 to 0.417 in 2011 and the coefficient of income inequality, respectively, from 13.5 to 16.2 times [19] . As a result, about half of the total amount of income is concentrated in the wealthiest fifth of the population group, about the same account for all the other groups (Figure 4).

According to the academician D.S. L’vov, it was because the “new” class of managing directors and managers of joint-stock companies was basically removed from social control and legal responsibility for the efficient use of the assets owned by these companies. One of the strategic owners of corporate enterprises—the state— basically pulled out of the management of the property which it owned” [23] .

Such a high level of income differentiation is partially due to the excessive differentiation of labor remuneration, which remains one of the key sources of income. A research of the Institute of Social and Economic Studies of Population, Russian Academy of Sciences, highlighted the formation of a mechanism, which promotes accelerated growth in the highest wages in Russia. Under this mechanism, a 50% - 60% increase in labor remuneration is used to increase the remuneration of 20% of the highest paid employees in view of structural imbalances that are manifested in the lower payment for highly skilled labor compared to less qualified workforce. As a result, the average wage of 10% of the highest paid employees exceeds the wage of 10% of the lowest paid employees by 26 - 28 times [24] .

Unjustified social inequalities engender social tension in a society, as well as disintegration and conflict of social forces, and, finally, turn into a social threat to national security. It is not accidental that a decline in the social and economic inequality of the population is viewed as a highly important strategic objective in the national security doctrine.

Unjustified differences in salaries of different categories of workers and the distribution of income had a negative impact on the social and economic stratification of the population of Russia (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Distribution of the total income of the population in the Russian Federation in 2011 by 20% groups [20] .

Figure 5. Decomposition of the social structure of the population of Russia, 2012. Calculated for [19] .

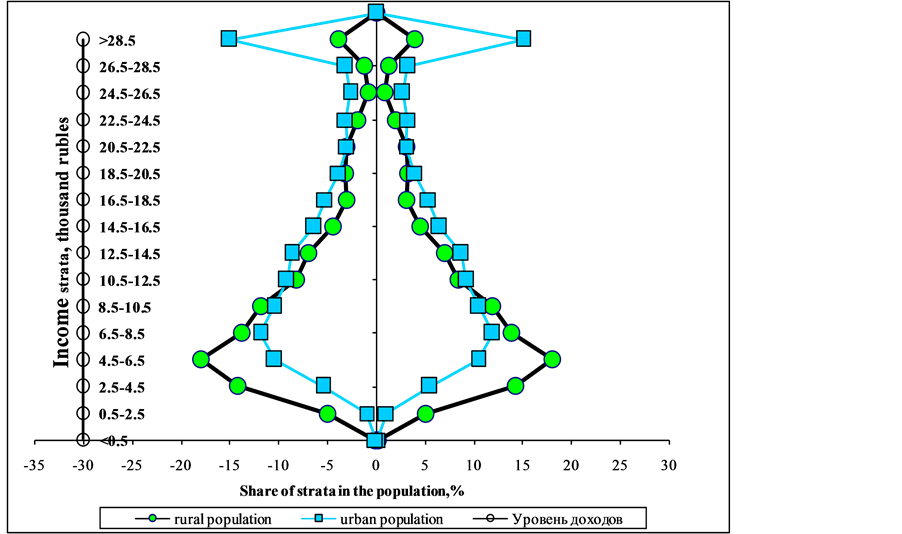

According to sample surveys for the IV quarter of 2012, the dominant groups of the rural population are poor and low-income groups. Among the rural population poor strata with incomes below the subsistence minimum (LWs) was—27.5%, low-income groups were (1.1 to 2.0 LWs)—42%. In total, about 70% of the rural populations have incomes that do not exceed the minimum that is required for the simple reproduction of the labor force. Revenues from 2.1 to 6 LWs are about 30% of rural residents. Income provide developing standard of consumption, are 2% - 3% of the rural population. Archaism of the social structure and rural poverty are evident. Urban’ social stratification is fewer shares of the poor and a larger share of the middle-groups. Rich population is represented by a very small cohort, which have about half the total amount of income.

Perspectives of development of the middle class are associated with a wide access to business income. However, according to experts, enter in the middle class at the expense of access to entrepreneurial income can no more than 5% - 8% of Russian families. While from 1995 to 2010, the share of income from business activities in the Russian Federation decreased from 16.4% to 8.9% [20] . This means that the overall economic environment in Russia does not create preferences for the development of entrepreneurship, which can serve as an engine of growth of the middle class. Meanwhile the expansion of the middle class is an important result and a driver of economic and social development.

3.3. Social Expenditures State

Thus, it is not only business that should be blamed for the fact that managers cannot control their appetites. What about the state? It has a very powerful instrument for income regulation in its disposal, namely, tax policy. Members of the parliament, academics, practitioners, and representatives of civil society go on highlighting the relevance of a shift from a flat rate individual income tax to a progressive one. However, the government does not take these arguments into account. By the way, Russia is one of the few countries applying a flat rate income tax. Shifting to a progressive tax system can be a vigorous mechanism for income regulation; it allows one to more equitably distribute the tax burden between the rich and poor and to stimulate the development of an income based population structure, which is in line with the indicators that are recognized in most industrialized countries as the most socially and economically preferred. Specifically, the ratio between the average incomes of 10% of the richest citizens and 10% of the poorest ones is between 6 - 8 times. In Russia the difference in incomes of the poorest and the richest is—16 times and higher. This difference in income is considered as critical and is a sign of excessive social tension in society.

Therefore, the incomes of taxpayers surpassing a tenfold increase in the value, which is taken for the income level of the “poor,” should be subject to a “limiting,” rather than a “favorable,” tax. Expert assessments show that under the current taxation system the burden of impending payments significantly differs for the least and most well-off population groups. If we compare taxpayers with monthly incomes of 5000, 30000, 60000, and 100000 rubles, under an income ratio of 1:6:12:20, the share of money left for them after making all impending payments (in their free disposal) is 1:20:42:72, respectively, while the burden of impending payments for the poorest (with a monthly income of 5000 rubles and a burden of −76.6%) is by 4.7 times larger than that of the richest people (with a monthly income of 100,000 rubles and a burden of 16.2%) [24] .

In addition to taxation policy, the state has another means of influence on human capital development, namely, public investment in health, education, and culture. However, statistics show that this investment is not sufficient to compensate for the lack of individual investment because of the low wages. Thus, according to data for 2009, the per capita public spending on health and education in Russia amounted to 5.4% of the GDP, while in the United States such investments accounted for 16.2%, France—11.7%, Germany—11.3%, Canada—10.9%, Norway—9.7%, in Japan—by 8.3% of the GDP. Planned for 2020 spending level of public funding for the reproduction of human potential does not eliminate this gap [25] .

In contrast to the global patterns of increasing public spending to perform advanced functions of the state (the development of intellectual and human potential—spending on education, health, science and economic development), in Russia the majority of public spending goes to perform traditional functions (defenses, law and order).

According to Academician S.Yu. Glaz’ev, the continuous insufficient funding of science, education, and healthcare in Russia, which is twice as small as the world standard, is affecting those areas where modernization and a drastic wage increase are critically important. It will therefore aggravate the irreversible trend of their degradation and will basically make the implementation of the innovation scenario impossible.

Only a radical change in social policy can make a significant difference and create favorable conditions for human development as the main driving force for rural developmentю

4. Conclusions

This period during the 1990s is characterized by active state intervention aimed at reorganizing the collectively owned agricultural sector and promoting a new institutional framework for the development of new forms of management.

But the sharp turn from a planned economy to a market economy in Russia during the 1990s based on freemarket ideology has produced adverse economic and social effects. Collective farms were destroyed, leaving a space filled with small non-profit family farms and a few peasant farms. It can be argued that a major reason for this failure is that the model of agrarian relations imposed from above has been taken into account neither traditions and historical experiences specific to rural Russia, nor the symbiotic relationship between “collective” and “individual” in Russia. “Collectivism and authoritarianism—the main features of traditional Russian economic culture, “imprinted” in the national mentality” [26] . Cultural factor, in my opinion, was one of the main barriers to the development of private farming in Russia.

The sharp reduction in state supports of agricultural producers was a serious blow to the agricultural production. Transition in the 2000s leaded to a more balanced policy of relatively large and small producers. Increased states support agri-food, which improve the living conditions of the rural population, and in general have yielded positive results. Crucially, pre-reform levels of agricultural production were not reached.

Becomes evident conclusion about the need to modernize the agricultural sector and improve the quality of life of the rural population through a radical change in social policy in the following areas:

• increasing the number of high-paying jobs and enhancing the population’s motivation to boost their competitiveness in the labor market, following the expansion of the economy’s innovative segment;

• anticipating investment in the development of the social infrastructure and human development;

• balancing the distribution of social responsibility among the government, business, and the population, with the state taking a leading role in ensuring minimum social guarantees;

• developing institutions responsible for the insurance of social risks based on a partnership between the government, business, and the population.

References

- Kalugina, Z.I. (2001) Paradoxes of Agrarian Reform in Russia: A Sociological Analysis of Transformation Processes. Novosibirsk, Izd. IEIE SO RAN.

- Manzanova, G. (2011) Traditions and Innovations. Experience Comparative Analysis of Agrarian Communities of Buryatia (Russia), Russia and Other Countries. Ulan-Ude: BSC.

- Nechiporenko, O. (2010) Rural Communities in Changing Russia: Innovation and Tradition. Siberian Scientific Publishing House, Novosibirsk, 302.

- Nefedova, T. (2003) Rural Russia at the Crossroads: Geographical Essays. Moscow, Novoe Izdatelstvo.

- Patsiorkovski, V. (2003) Rural Russia. 1991-2001. Finance and Statistics, Moscow.

- Velikii, P. (2012) Russian Village. The Processes of Post-Soviet Transformation. Saratov, Nauchnaja Kniga.

- Rastyannikov, V.G. and Deryugina, I.V. (2004) Model of Agricultural Growth in the XX Century: India, Japan, USA, Russia, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Moscow: Izd. IVRAN.

- Kalugina, Z. (2007) Institutional Traps in the Agrarian Transformation in Russia. Eastern European Countryside, 13, 69-82.

- Russia in Figures (2003) Stat. Bull., Moscow, Rosstat, 406.

- Priority National Project. Development of the Agro-Industrial Complex.

http://www.rost.ru/projects/agriculture/agr6/agr61.shtml - Uzun, V. (2005) Large and Small Business in Russian Agriculture: Adaptation to Market. Comparative Economic Studies, 47, 85-100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ces.8100078

- Deryugina, I.V. (2010) The Agricultural Sector in Russia: Cycles and Crises 1998-2009 Period. Problems of Statistics, 3, 67.

- (2009) Russian Statistical Yearbook. Rosstat, Moscow, 412, 418.

- Beck, U. (2000) Risk Society: Towards an Another Modern. Translated from the German Sedelnik, V. and Fedorova, N., Progress-Tradition, Moscow, 21.

- (2012) Russia in Figures. Stat. Bull., Rosstat, Moscow, 257; (1999) Russia in Figures. Stat. Bull., Rosstat, Moscow, 204; (2003) Russia in Figures. Stat. Bull., Rosstat, Moscow, 202; (2004) Russia in Figures. Stat. Bull., Moscow, Rosstat, 208; (2000) Russian Statistical Yearbook. Moscow, Rosstat, 362.

- Giddens, E. (1994) Fate, Risk, Security. Thesis, 107-134.

- Bobkov, V.N., Litvinov, V.A., Gulyugina, A.A. and Zubrilin, Y.V. (2006) Key of Indicators of Incomes and Living Standards in the Federal Districts of Russian Federation in Second Quarter of 2006. Monitoring Dokhodov i Urovnya Zhizni Naseleniya, 29-50.

- Bobkov, V.N. (2008) Difficult Recovery of Russia. Uroven Zhizni Naseleniya Regionov Rossii, 8-18.

- (2012) Income, Expenses and Consumption of Households in the Fourth Quarter of 2012: The Results of Random Analysis of the Budgets of the Households. Moscow, FSGS.

- (2012) Russian Statistical Yearbook. Moscow, FSGS.

- Belyaeva, L.A. (2009) The Living Standard and Quality: Problems of Change and Interpretation. Sotsissledovaniya, 33-42.

- Glaz’ev, S.Y. (2010) Coming Just Three Regular Lost Years (about Forecasting and Budget Parameters 2011-2013). REZh., 8.

- L’vov, D.S. Russia: The Frontiers of Reality and Outlines of the Future.

http://www.zavtra.ru/cgi/veil/data/zavtra/06/679/31.html - Chereshnev, V.A. and Tatarkin, A.I. (2008) Social-Demographic Safety of Russia. Ekaterinburg: IE UrO RAN, 136.

- (2011) Report on Human Development in the Russian Federation. Modernization and Development of Human Potential. M. http://www.undp.ru/documents/nhdr2011rus.pdf

- Nureev, R. and Latov, J. (2013) From “Oriental Despotism” to “Average-Weak Capitalism”: The Ragged Path of Institutional Development of Imperial Russia. Universe of Russia, 3-40.

NOTES

1Private households plots—a form of informal non-entrepreneurial activity for the production and processing of agricultural products.

2In the fourth quarter of 2012, the minimum consumer budget in the Russian Federation was 6705 rubles for the entire population, 7263 rubles for the working population, 5281 rubles for pensioners, and 6432 rubles for children.