Modern Economy

Vol.5 No.9(2014), Article ID:48561,16 pages

DOI:10.4236/me.2014.59088

Eurasian Economic Community: Towards Integration. Economic Challenges and Geostrategic Aspects

Georgios L. Vousinas

Department of Economics, University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Email: vousinas@yahoo.com

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 28 February 2014; revised 28 March 2014; accepted 20 April 2014

ABSTRACT

The present study deals with Eurasian Economic Community (EurAsEC), a relatively new entity that appeared in the post-Soviet region, which tries to join the neighboring countries into a strong and structured union. The paper presents the integration steps that have been taken so far and examines the economic challenges faced as well as the geostrategic aspects. A comparison with the benchmark of the surrounding area, the European Union, is also undertaken in order to investigate both the similarities and differences among them and show if they could co-exist in the years to come. The main purpose of this study is to examine the reasons for the union’s formation, shed light on its economic prospects and highlight the newly established geostrategic conditions in such a crucial territory of the world.

Keywords:Integration, Union, Economic Growth, Geostrategy, Financial Stability

1. Introduction

The Eurasian Economic Community (EurAsEC) is an international economic organization designed to effectively promote the formation of a customs union and a single economic space among six CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States) countries: Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Moldova, Ukraine, and Armenia share an observer status. EurAsEC originated from the CIS Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia on 29 March 1996. The Treaty on the establishment of the Eurasian Economic Community was signed on 10 October 2000. On 7 October 2005 it was decided between the member states that Uzbekistan would join. Freedom of movement without visa requirements has been implemented among the members. A Common Economic Space for the community was launched on 1 January 2010. From the very outset, it has aroused great interest among politicians, public figures, scientists and the general public. Many people regard it as a military-political alliance and confuse it with the CIS Collective Security Treaty, while others see it as renewed bondage to Russia, since Russia has 40% of the votes and is the leading economic power. But the main purpose of the new association is the effective formation of a single economic space, with transformation of the Customs Union of these countries into a new international organization. The purpose of this paper is to describe the entity, examine the reasons behind its formation and shed light to its economic and geostrategic aspects with a look into the future.

2. The Structure & Integration Stages of the Customs Union

As practice showed, many decisions taken within the framework of the Community of Independent States, set up in 1991, were not being put into effect, and trade as well as economic cooperation within it was largely bilateral. In 1995, Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan proposed a new concept of multirate integration and signed a tripartite Agreement on a Customs Union, subsequently joined by Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Implementation of that document was entrusted to a trilateral intergovernmental commission. On 29 March, 1996, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia signed a Treaty on Deepening Integration in the Economic and Humanitarian Fields (Tajikistan acceded to it in 1998). Having noted the inadequate effectiveness of the trilateral commission’s work, the parties agreed to set up a standing Integration Committee as a working body for the formation of a Customs Union and for strengthening economic cooperation. An Interstate Council consisting of heads of state and government, foreign ministers and the Integration Committee chairman became the highest integration authority of the new grouping. The Integration Committee was vested with executive and coordinating functions, and all its decisions were taken by consensus. Costs were shared on a parity basis. All decisions and adopted international treaties were binding on the parties, but no sanctions were envisaged for their violation. As a result, some decisions were not implemented or were implemented only in part. The reason here was the lack of a full-scale document laying down the tactics of the formation of a common market of goods, services, capital and labor. In 1999, the parties finally prepared and signed a Treaty on a Customs Union and a Single Economic Space, which made it possible to raise integration processes within the CIS to a qualitatively new level. That treaty was the first full-scale document of its kind charting the immediate prospects of integration virtually in every area of the economy. Together with the treaty, the parties adopted a program for its implementation, providing for the preparation of more than sixty document drafts whose ideology and format had been coordinated, in principle, with all the participating countries. However, they didn’t put forward all the tasks in setting up a common capital, services and labor marketor specify all matters relating to a common industrial policy, choice of priority industries and establishment of a common market. Nevertheless, the treaty projected a level of integration for which all parties were actually prepared. In more than four years of work, the Integration Committee has managed to achieve a great deal. Thus, tariff and quota restrictions in the trade and economic sphere have been lifted, and a common customs tariff is being coordinated (for three countries, 60% of the tariff has been agreed, while Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are taking measures to accede to it step by step). Efforts are being made to solve problems of nontariff regulation, to adopt uniform trading arrangements in relations with third countries and to create a single customs territory. Certain understandings have been reached in the field of economic policy and the Basic Lines of Economic Restructuring in the Customs Union Member States for 2000-2005 have been adopted. Agreements on the mutual convertibility of national currencies and on the interaction of national monetary-financial systems have been signed and are being put into effect and a common payments system is being established. Real steps have also been taken in the humanitarian field: the parties have signed all the agreements in pursuance of their Statement on Ten Simple Steps To Meet Ordinary People, ensuring fuller satisfaction of the needs of the citizens of these countries in the fields of education, culture, public health, residence, citizenship and other social rights. Development of the theory of integration between the CIS countries has a significant place in the Committee’s work. As everybody knows, countries striving for integration are motivated by an urge to pool their resources and to create the necessary conditions for attaining higher levels of economic welfare and sociopolitical stability.

Economic prosperity and growth primarily depend on a growth of material production and saturation of the internal market with goods both as a result of domestic production and as a result of commodity exchange with other countries. In other words, primary importance is attached to commodity producers and to interstate efforts to create conditions for their efficient operation. So, the purpose of any integration-oriented cooperation is to give economic agents broader access to material, financial and labor resources, to the latest technologies, and also markedly to expand their opportunities for selling regionally produced goods on the single market of the integrating countries. Moreover, closer economic relations between countries within the framework of regional associations make it possible to create preferential conditions for the commodity producers of the integrating countries and, in particular, to protect them against competition from commodity producers of outside countries. However, in order to attain their ultimate goals, the integrating countries must display political will and, on grounds of economic expedience, coordinate their national legislation, gradually eliminate customs, tax, administrative and other barriers hindering the development of production on a mutually complementary basis, and agree on joint use of resources and sale of goods in the territory of the common market. The development of any integration grouping implies a gradual lifting of all restrictions on the movement of goods, services, capital and labor. But such lifting of restrictions is not an end in itself. Its aim is to create conditions for developing the production of goods and services. The integration process in the CIS countries differs markedly from standard world practice, since it involves newly independent states which used to be Union republics and where the advance toward real statehood and the transition to a market economy go hand in hand with the development of integration. Each new stage of integration can be attained only when the economy reaches a definite level. At the same time, the economic situation is bound to improve with the development of integration tendencies, which means that there is constant feedback between the two processes. Take the European Union (EU). Ever since its establishment, the Economic Commission for Europe has monitored the economic status of EU members, elaborated programs to stimulate the development of lagging regions, and taken measures to even out the basic macroeconomic indicators of the member countries, finally prescribing certain margins for these indicators without whose attainment no country can be admitted to the euro zone, the zone of the single currency [1] [2] . At the first stage of the integration process (establishment of a free trade area), the participating countries are not required to meet any specified conditions depending on the state of their economy, but at subsequent stages (formation of a Customs Union, establishment of a common market and a single economic space) the demands on the economic status of the integrating countries are increased. For the formation of a common market of goods, services, capital and labor, the partner countries should have a stable economy and similar economic regulation mechanisms based on market principles and on duly coordinated economic legislation, and should create equal conditions for their producers in the sphere of taxation, pricing and tariff policy. With the development of a capital market, parities are established between the national currencies, and the partner countries bear collective responsibility for their maintenance. That is why the burden should be distributed evenly, and the economic status of the integrating countries should be equal, since otherwise the weaker economy of one of the countries tends to turn into a kind of financial “black hole” for the stronger countries, which are obliged to shoulder the burden of meeting its financial risks. In the formation of a common labor market, countries differing markedly in terms of gross domestic product (GDP), export volume, and per capita budget revenue and expenditure will not be able to create equal conditions for the citizens of all the partner states, that is, to ensure an agreed level of average wages, pensions and social benefits or to establish minimum social standards. Stabilization of the basic macroeconomic indicators is a key condition of coordinated structural changes in the economies of the participating countries. It creates prerequisites for stepping up economic activity and for promoting integration processes. That is why the members of the Customs Union should increase their GDP and foreign trade volumes, lower inflation, reduce budget deficits, stabilize national currencies, and optimize refinance rates. Steady growth of the economy and living standards calls for structural and technological balance on the level of plants, industries, regions and partner countries, that is, the members of the Customs Union should overcome the disproportions in the distribution and development of production. In addition, it is necessary to reduce costs per unit of social product through vigorous introduction of resource-saving technology, and also through a transition from intensive to largely extensive reproduction. In order to even out the economic development of the integrating countries, it is necessary to fix lower limits for the basic macroeconomic indicators, as agreed at the stabilization stage. These tasks can be resolved by ensuring growth in the real sector of the economy, with assistance to lagging regions which cannot attain the agreed standards on their own. For the purpose of helping such lagging regions, the partner countries should form a common budget and determine the principles and points of application of such assistance [3] . In the EU, for example, financial assistance is given to regions where GDP per capita does not exceed 90% of the average for the union. The common EU budget is formed of customs duties and deductions (at a rate of 1%) from receipts of value added tax (VAT). In 2000, the EU countries reached an agreement to change the budget formation method depending on the GDP of each country. Programs in support of lagging regions have enabled 11 of the 15 EU countries to enter the zone of the single currency. As regards the Customs Union, statistical data and estimations for 2012 to 2015 show a measure of economic stabilization in the participating countries. The Integration Committee carries out a regular analysis of their socioeconomic development. However, substantial differences in their basic macroeconomic indicators have yet to be overcome, so that in terms of economic development levels these countries could be tentatively divided into two groups. The first group includes the financially strong countries, Kazakhstan and Russia and the second, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Provided that Belarus manages to stabilize the exchange rate of its national currency, reduce inflation rate and gets its banking system modernized, it could join the first group, since all its other indicators are quite up to the mark, whereas Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan need a period of around ten years to reach per capita GDP and export levels corresponding to the first group [2] . However, it is necessary to follow without exceptions and delays the road of stabilization and adaptation of their economic levels or else, any further development and strengthening of integration processes is mathematically impossible. The following Tables 1-9 show the main economic indicators (real and estimations) of the EurAsEC countries for the years 2012 up to 2015 that justify the existence of two-speed economies but also the potential capabilities [4] .

So, the Integration Committee’s theoretical economic research and analysis of these countries show the need

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2013.

Source. International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2013.

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2013.

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2013.

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2013.

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2013.

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2013.

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2013.

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2013.

to improve and coordinate development processes and to strengthen cooperation in the real economy, especially in related and complementary industries. But the decision-making arrangement that exists within the Customs Union and the functions of the Integration Committee do not allow the partner countries to realize these opportunities in full measure, which means that the Customs Union is in need of structural and organizational change. On the strength of its experience over a period of close to five years, the Integration Committee has brought out a number of deficiencies in CU’s activity. Thus, decision-making by unanimity has proved to be an ineffective tool. The experience of the European Union shows that the European integration process took a much more dynamic turn only after the signing of the Single European Act (1986), according to which decisions were no longer taken unanimously, but by a majority of votes. The absence of supranational functions makes it impossible to follow a joint foreign trade policy as a basis for the formation of a Customs Union, so that decisions on foreign trade activity are taken by each country independently, without due account of the interests of its partners. Economic instability, dependence on external economic and political factors, and pressure from international organizations (like IMF) often induce the partner countries to act in breach of earlier understandings or fail to fulfill them altogether. Differences in national legislation lead to lack of coordination in the timing of ratification and entry into force of international treaties and decisions adopted by the partner countries, so making it impossible to put them into practice. Despite the approval and enactment of Regulations Governing Draft Legislative Acts, the participating states often act solely in pursuit of their own national interests and take decisions without coordinating them with their CU partners on the claim of a payments deficit, urgent requirements of the domestic market, potential or real damage imposed on domestic producers by competition through imports of similar goods and so on. The reason for many of these troubles is that the Integration Committee is not vested with such powers, enabling it to ensure fulfillment by the parties of every adopted decisions [5] . The Committee has repeatedly raised various doubtful questions and brought them before the Interstate Council, but the partner countries still have an opportunity to adopt unpopular measures and thus, ruining the Customs Union. Someone could note that even supranational functions are not able to solve the given problem, for what is necessary here, first and foremost, is a collective awareness of the need for such an integration union and of its advantages. In the absence of a system of sanctions for breach of obligations, each partner country is enabled to disregard collective decisions and to act solely in accordance with its national interests, while ignoring the collective needs of the Customs Union. The insufficiently high status of the Integration Committee does not allow it to apply tough measures against the offending party. Although the Treaty on Deepening Integration in the Economic and Humanitarian Fields, signed on 29 March, 1996, was registered with the United Nations, the Committee does not have the status of an international organization. Among the prerequisites for its formation we could include the incipient economic development, the attainment of a specific level of integration and also the complicated political and economic situation in the world, which acts as a boost to integration processes in the post-Soviet region.

3. Banking Integration in the EurAsEC Member Countries

Although the development of banking systems in EurAsEC member countries has been successful in various ways, it is however not without certain persistent problems. These banking systems have evolved significantly over the past fifteen years. More specifically, market reforms in the banking section have established two-tier banking systems and the legal framework for central banks and financial institutions. Financial institutions of the member countries have been increasing their capitalization in all the recent years. For example, in 2006 solely, their combined as sets increased by over 60%. Some member countries have switched to International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), which have helped to ease risk-assessment and increase the transparency of banking operations [6] . Banking regulation is largely conducted in line with international standards, following recommendations from the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Most of the member countries have increased the minimum size of authorized capital to €5 m, thus providing a strong increase of the capitalization of financial institutions. Some countries have gone further by adopting deposit guarantee schemes, which, of course, makes up a very significant step forward in the evolution of their banking systems. Another positive trend concerns the growing transparency of the national banking systems and the increasing role of foreign capital, which have helped to boost the conditions of competition in the market and improve standards in banking. Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) by Russian and Kazakh banks have become very common in the previous years. Nevertheless, in spite of the considerable improvement in EurAsEC member countries’ banking systems, regional banking markets are still poorly integrated and differ widely in terms of the structure, size and value of their operations. For example, the combined assets of all EurAsEC banking systems stood at $625 billion as at 2007. Furthermore, these assets are not evenly distributed among EurAsEC member countries as Russia accounts for over 85% of the total assets. The second biggest banking system that of Kazakhstan, accounts for only 11%. Belarus and Uzbekistan account for 2% and 1% respectively, while the Kyrgyz and Tajik banking systems’ combined share is less than 1%. A considerable high level of concentration of the banking assets is also apparent within national banking systems. Most assets and capital are shared by a limited number of financial organisations, which in Soviet times were mainly regional branches of Sberbank or Vneshtorgbank. Despite quite high growth rates in banking assets in the six countries, their role in servicing the economy is still insignificant. The coefficient of financial intermediation, calculated as the ratio of assets to Gross Domestic Product (GDP), is low in most of the countries in comparison both to developed and developing countries (Table 10).

The role of the banking system is greatest in Kazakhstan where assets account for 86% of GDP. The limited role of banking systems in the economies of the EurAsEC member countries makes them considerably dependent on global financial markets. Around half of all loans in Russia are issued by foreign banks. Cross-border loans today constitute approximately 52% of the liabilities of Kazakh banks. The Kazakh banking system suffered the adverse impact of this dependency in 2007 when, due to the US subprime mortgage crisis and the following liquidity crunch, ratings agencies downgraded Kazakhstan’s sovereign rating. The structure of each EurAsEC member’s banking system has a significant impact on its development. The role of state capital is stillquite high in some member countries. For example, state-owned banks account for over 70% of total banking assets in Belarus, 45% in Russia and more than 90% in Uzbekistan where the banking system is the least transparent. This high proportion of state capital affects the banks’ ability to perform their financial intermediation function and distorts competition. Many state-owned banks enjoy preferential status in connection with statefunded projects, and major public organizations keep their accounts in these banks. State-owned banks also rely on government support in tough times, so despite the significant development of these banking systems, they remain highly vulnerable. According to international ratings agencies risks in the CIS banking system are among the highest in the world, due to the existence of the grey economy, the considerable debt liabilities of financial organisations, widespread distrust of banks, corruption issues, the poor quality of loan portfolios and the existence of a kind of “protection” to specific banks [7] . There is no doubt that the banking systems of EurAsEC member countries enjoy different stages of development. Kazakh and Russian banking systems play a crucial

Table 10. Banking sector indicators in EurAsEC countries (2007).

Source: Interfax-1000: Banks of CIS Countries; World Economic Outlook Database, Oct 2007.

role in this region. However, the banking systems of the member countries are highly unlike and there is huge variance in their structure, extent of operations and level of development. Considering the current level of financial cooperation among EurAsEC countries, a good idea could be the creation of a regional capital market in the standards of the Asia Pacific states which chose to reduce their dependency on foreign sources of funding by developing aregional bond market that is less vulnerable to global crises. This market can be a very effective tool which reduces exposure to currency risk and keeps resources within the region in long term basis. Of course supplementary measures have to be taken so as to help address financial market volatility and more specifically, propermacro economic policies, structural reforms and strong regulation mechanisms by all the members. It is also necessary to enhance private sector participation in the banking system in order to meet financial needs and improve the investment climate in the region. However, there are certain obstacles like the absence of sovereign ratings for some of the countries and the fact that such amechanism could be launched only in a limited number of countries (Russia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine and Belarus). Given their present status, a substantial role in the model of CIS financial markets could be played by multilateral development banks such as the Eurasian Development Bank [6] . The Eurasian Development Bank (EDB) is a regional development bank established by the Russian Federation and the Republic of Kazakhstan in January 2006 so as to promote economic development and facilitate integration in the Eurasia zone. The Bank currently has six member states, including Armenia, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Other states and international organisations are capable of becoming members by signing up to the Bank’s founding Agreement. EDB’s charter capital exceeds $1.5 billion, a total made up of contributions by its member states. More specifically, Russia has contributed US$1 billion, Kazakhstan US$500 million, Armenia US$100,000, Tajikistan US$500,000, Belarus US$15 million and Kyrgyzstan US$100,000). Any increase in the charter capital is at the discretion of the Bank’s Council to approve it or not. The Bank has the status of an international organization due to the fact that in January 2013, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) recognised EDB as a multilateral financial institution. Capital markets can be developed only through the redistribution mechanism operated by multilateral development banks (raising funds through bonds and transforming them into loans). As a result, post-Soviet countries would be able to place their funds not on the global financial markets but in the former Soviet space, helping not just to retain capital in the region but also to promote economic growth. This mechanism of developing economies and financial markets will have a wider geographical range compared to the development of the bond market. Conclusively, the creation of a formal regional common financial market would be beneficial for all the member countries as a major step to increase stability and boost economic growth.

4. The Aims of the New Union

In the field of foreign trade and customs policy, the main purposes of the EurAsEC are summed up to the following:

Ø improvement of the free trade regime

Ø formation of a single customs tariff and a single set of nontariff regulation measures

Ø introduction of a consolidated system of preferences

Ø the elaboration of a shared position in the relations with the World Trade Organization (WTO) and with other international economic bodies (like World Bank and IMF)

Ø the introduction of unified rules of exchange regulation and control

Ø the development of an effective payment and settlement mechanism

Ø the ensurance of an economic security on the Community’s external borders

Ø the strengthening and fortification of these borders on order to prevent customs offences like smuggling etc.

In the field of economic policy now, the partner countries are to coordinate their structural reorganization efforts; to elaborate and implement joint socioeconomic development programs; to establish a common payments system, and to ensure the interaction of monetary-financial systems. They are also to create equal conditions for production and business activity and for access to foreign-investment markets; to form a common market of transport services, an integrated transport system and a common energy market; to carry on joint research and development along priority lines of science and technology; and to develop a unified system of legal regulation, formation and activity of financial and industrial groups on a multilateral and bilateral basis [8] [9] . In the sociohumanitarian field, the Community states are planning to develop adequate national systems of education, science and culture; to ensure minimum social standards, and to grant their citizens equal rights in receiving an education and medical assistance throughout the territory of the Community.

5. Eurasian Customs Union (ECU) & European Union (EU): Coexistence or Rivalry?

The main significance of the ECU is its departure from previous similar actions for integration in the post-Soviet era. The first and best-known of these was the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), which proved a mere vehicle for channeling the orderly disintegration of the Soviet Union, rather than the re-integration of its former republics. Figure 1 shows the geographic range of the European Economic Area and Common Economic Space.

By the mid-1990s Russia’s focus shifted to investing in smaller groups and the origins of the ECU date back to 1995, when Russia signed a treaty for the formation of a customs union with Belarus and Kazakhstan (Kyrgyzstan joined in 1996 and Tajikistan in 1997). This initiative retained the ineffective CIS institutional formula [9] . Putin’s accession to the presidency, however, added a new impetus to the project and in 2000 the grouping was transformed into a fully-fledged international organization, the Eurasian Economic Community (EEC), although many of the old problems persisted, putting its effectiveness in question. Nevertheless, the middle of the 2000s saw the emergence of a vanguard group of states. The leaders of Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan decided to set up a customs union in 2006, and swiftly established a Customs Union Commission as a permanent executive body. The group launched a common customs tariff in January 2010, where in July 2010, the common customs territory was declared and the Customs Union Code, the key regulatory document, adopted. In July 2011, another milestone occurred with the decision to eliminate internal physical border controls between the member states. But the ambitions of the members didn’t stop there: the member states’ aim is to progress towards an economic union with a common market of goods, capital and labor and the operation of common macroeconomic, competition, financial and other form of regulation, including the harmonization of policies such as energy. The launch of the Eurasian Economic Union is due to be fulfilled in January 2015. While we need to retain a degree of healthy skepticism about the transition to the Eurasian Economic Union, developments so far signal a pivotal change in integration patterns. The ECU offers a forward looking integration model that is a clear improvement on previous initiatives in terms of both design and implementation. The Union operates in the context of Russia’s accession to the WTO: while Belarus and Kazakhstan remain outside it, Russia’s accession protocol is designed to become an integral part of the legal framework of the ECU [10] . So the Union represents a modernized economic regime, very different from previous attempts at regional integration within the post-Soviet space. Beyond any doubt, the question still remains whether Russia will be bound by this multilateral regime. Previous regional groupings shared a high level of asymmetry, allowing Russia to use its superior bargaining power and avoid being bound by potentially costly decisions [11] . Yet there are indications that Russia may be prepared to move towards greater multilateralism and, at least in theory, it can be outvoted by its

Figure 1. Map of European Economic Area & Common Economic Space.

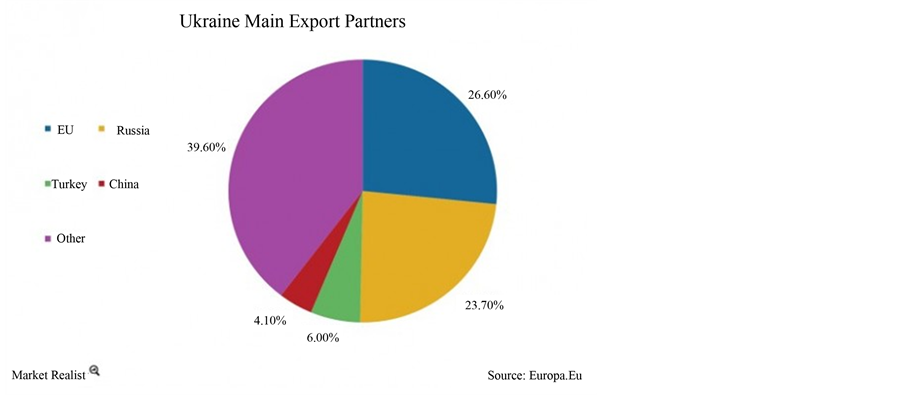

partners on certain types of decision. It is made clear that much of the progress so far has been dependent on the personalities of the leaders in the three countries (Putin, Nazarbayev and Lukashenko), making the union vulnerable to any leadership changes. But despite the reliance on personalities, the ECU is different from its predecessors not only in terms of the political will that is driving it forward, but also, critically, in terms of its institutional effectiveness. The removal of internal borders, despite transitional periods in relation to the Russia-Kazakhstan border, symbolizes this and it means that the ECU cannot be reversed without severe cost making the whole project very likely to stay. This ambitious deepening of the ECU has coincided with a drive to widen it by making it a “center of attraction”. Russia has viewed the ECU as a core for the wider integration of its “near abroad”, and in Kyrgyzstan, for example, accession to the ECU is high on the political agenda. But it is the approach to Ukraine (the main battleground as mentioned before) that illustrates the shift in Russian policy more clearly, because it is presenting the ECU as a “governance-based” vehicle in direct competition with the EU. The ECU is the vehicle through which Russia is increasingly engaging in “normative rivalry” with the EU in the so-called “shared neighborhood” (i.e. Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia) [12] , [13] . Russia has begun to compete in a domain where until now the EU has enjoyed a monopoly. The European Union, which launched the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP) and the Eastern Partnership in the 2000s, has been seen and regards itself as the primary source of modernization and improved governance in the post-Soviet space [14] . It promotes a rule-based, future-orientated economic integration regime designed in accordance with its own governance model via an offer of Association Agreements, Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Areas (DCFTA), Visa Facilitation Agreements and full visa liberalization in the long term, but not membership. The DCFTA goes beyond a “standard” free trade agreement, entailing major changes in the regulatory framework of the country associated with the EU in a wide range of areas. The expected benefits of such an agreement are capabilities so far lacking in most of the eastern neighbors: the ability to sustain reforms or a degree of confidence in the economy due to improved institutions and well-structured system of economic governance. The EU has offered Association Agreements, with the DCFTA, to all post-Soviet countries in Europe which are also members of the WTO (i.e. Ukraine, Moldova, Armenia and Georgia).So far the EU has not responded in any concerted way to the anti-DCFTA campaign in Ukraine. It is no doubt relying on its own “power of attraction” and Ukraine’s long-standing “European choice”. Recurring fatigue and disillusionment with the country mean that the EU has largely failed to promote this flagship and pioneering agreement effectively in Ukraine. Russia, meanwhile, is not relying solely on promised economic gains for Ukraine, and is backing up its invitation with a traditional “carrot-and-stick” approach. The incentive comes in the form of a reduced price for gas, benefiting Ukraine by up to $8 billion per year. The penalty, on the other hand, would consist of economic sanctions against Ukraine, which would be primarily justified in terms of the negative implications for Russia of the EUUkraine DCFTA. Russia is implying at deploying a set of mechanisms in order to “persuade” Ukraine of the “benefits” of the ECU. This reinforces the perception of the initiative as a vehicle for projecting Russian power, particularly as the Russian approach also makes it more difficult to resist the “offer”. But the question is what punitory measures could Russia introduce? These could range from applying anti-dumping tariffs and limiting imports of Ukrainian food products through the application of phytosanitary standards for plant and plant products, to lowering the quotas for steel pipes which constitute a key export for Ukraine. Selective, targeted sanctions have already been repeatedly deployed by Russia against states such as Moldova, Ukraine or Georgia, which are deemed to be pursuing unfriendly policies. But how far could Russia go in “punishing” Ukraine? Russia’s membership of the WTO precludes it from using certain punitive trade measures, and Ukraine, as an existing member, could resort to WTO mechanisms to address politically-motivated trade sanctions. However, Russia may take extra-legal measures, in contravention of WTO rules. Ultimately, it is difficult for Ukraine to make a choice based on a prediction of Russia’s tendency to break the rules of the organization to which it has just acceded [15] . This campaign complicates Ukraine’s already difficult relations with the EU. The signing of the Association Agreement has been put on ice due to the deterioration of democratic standards in Ukraine, as evidenced above all by the political prosecution of opposition figures. These prosecutions have been loudly condemned by EU institutions and member states as a clear breach of democratic standards and the rule of law. On the other side, the ECU does not require its current and prospective member states to conform to any democratic standards. Ukraine is being invited to join without any specific political conditions required and given the fact that Russia’s offer comes at a sensitive moment in Ukrainian-EU relations, it represents a significant counterweight to the EU’s democratic demands. The campaign to persuade Ukraine to abandon the Association Agreement with the EU could be seen as a short-lived attempt to attract the country at a time when the authorities have declared their interest in concluding the Agreement rather than opting for the ECU. However, this is not just a matter of short-term choice but also a longer-term conflict of interests. Even if and when the Association Agreement is concluded, its implementation will be prolonged, costly and highly sensitive for Ukraine in both political and economic terms. Ukraine’s dependence on the Russian market means that the country has to adapt simultaneously to two competitive integration regimes, the EU and the ECU. Therefore the creation of the Eurasian Customs Union (ECU) could enhance Russia’s position in the post-Soviet era at the expense of the EU. However, as the most important player, Ukraine would have to be persuaded to abandon its EU Association Agreement to join the ECU instead and contrary to public’s opinion. There are very recent the examples of mass social demonstrations in favor of a decision to join the EU. Since the collapse of the USSR, various attempts have been made to (re)integrate the newly independent countries, but they have proved mostly ineffective [16] . These initiatives have been seen as vehicles for Russia’s traditional dominance of the region, expressed in a mix of crude power and institutional weakness, and wrapped up in historical discourses. The formation of the Eurasian Customs Union (ECU) appeared in order to change this. While its economic aspect remains debatable, the ECU has been formed as a rule-based organization conforming to World Trade Organization (WTO) regulations and modern international norms. At the same time, it is clearly seen by Russia as a vehicle for reintegrating the post-Soviet space and offering a modernizing alternative to the EU. This is particularly significant for Ukraine, where Russia has been actively promoting the ECU as an alternative to the EU integration mechanism. Given the apparent viability of the ECU, this rivalry is likely to grow and will require other international organisations, such as the EU, to adjust their strategies. But at this point, we are going to examine the two choices that exist for Ukraine aka ECU and EU, from clearly economic perspective. The following Figure 2 shows the destination of Ukraine’s main exports.

As seen in the above figure, EU and Russia are almost even, consisting together half of the country’s exports. So the question that arises is what Ukraine has to lose if it chooses one of the two unions. Currently, Ukraine exports $17 billion of goods to Europe and $16 billion to Russia. If Ukraine signs a deal with the EU, trade with Russia could disappear, which Russia estimates would cost Ukraine 35 billion euros. This is much larger than the potential savings of 487 million euros a year if it signs a free trade agreement with Europe, eliminating about 95% of customs duties [17] . Of course, Russia’s estimations may be exaggerated, but it’s rather a significant threat. In order to comply with new trade standards, Ukraine would also be required to adopt approximately350 laws, which is not only costly but also time-consuming [18] . Moreover, following Kiev’s recent decision to shelve the EU deal, let’s look behind that. Taking into consideration the details of the deal and the current state of Ukraine’s economy, it’s clear that Kiev had justifiable reasons not to rush into the EU trade zone. The country’s decision came after long negotiations with the EU. Ukrainian officials said repeatedly that the country would inevitably face substantial losses if Russia decides to close its borders to Ukrainian goods and restrict bilateral trade. As the EU failed to offer immediate benefits that would cover such losses, Kiev deemed it necessary to suspend the talks. The cause of this failure can be summarized to the following:

Figure 2. Ukraine’s main export partners.

Not any financial guarantees

While EU has been demanding political and economic concessions from Kiev, it didn’t provide any financial guarantees. Indeed, ignoring the Ukrainian government’s concerns of an $8 billion loss before the end of this year, the EU offered 1 billion Euro aid. And even that amount was accompanied by demands to decrease budget deficit through potentially socially destabilizing cuts. So it seemed clear to the Ukrainian authorities that there won’t be any kind of financial aid from EU combined with the major loss of money derived from Russia’s measures to protect its market.

Losses of trade

If Ukraine becomes a part of a free-trade zone with the EU, Russia would have to seal its previously “open” border with its neighbor, for the fear of a flood of uncontrolled and untaxed goods that would ruin Russian industries. And it is true that the trade and customs relations with Ukraine are currently based on entirely different set of rules with literally “zero export-import tariffs”. At the same time, for Kiev the EU market will hardly be a substitute for the Russian market, as Ukrainian goods would not be as competitive in the Eurozone. Currently, almost a quarter of Ukraine’s exports go to Russia as demonstrated in the above mentioned figure. Moreover, Ukrainian producers would find themselves facing increased competition from European imports, prompting a number of experts to suggest that a range of domestic industries would fail to survive European integration.

Prices of gas

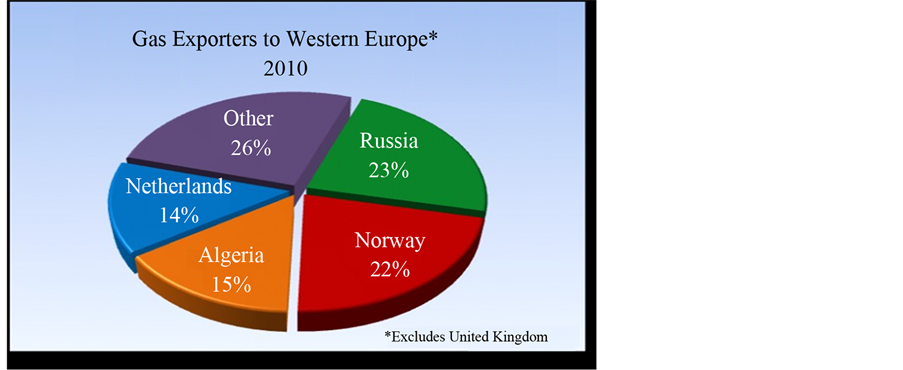

Other demands that scared off Ukraine from rushing to the EU had to do with gas prices and tariffs for domestic consumers. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) recently imposed a demand to drastically increase the gas bills of Ukrainians while freezing the salaries at the current level and doing additional budget cuts. Ukraine would have to increase domestic gas tariffs anyway, if it wants to join the EU, while it repeatedly had problems over late payments for the imported gas with Russia. The country has recently run into a gas debt of $882 million to Gazprom, although Ukrainian officials promised to pay it all back “by the end of the year”. Another piece of the gas puzzle is Ukraine’s gas pipelines, which are in decrepit condition. Gazprom has offered to buy the lines, an offer state-owned Naftogaz has so far rejected. Russia has said it won’t upgrade Ukraine’s rapidly aging pipe system, which delivers about a quarter of Europe’s Russian gas. Having received no promise of compensation for all the potential economic damages from aligning with the EU, Kiev now wants to create a three-party commission with Brussels and Moscow to find a way to alleviate those losses. But as all the major Russian pipelines of Gazprom go through Ukraine, and the latter is energy dependent to it, it isn’t economically affordable to reject the ECU proposal. And as seen in the following Figure 3, Gazprom is responsible for a third of all gas imports to Europe, so it seems wrong also for the EU to alienate Ukraine from Russia [19] .

The latter is also strongly documented by the following Figure 4 which shows that Russia is the main gas supplier of Europe [20] .

6. Concluding Remarks

The future of the EurAsEC shall depend on the practical results in stepping up cooperation in the real sector and in building a viable integration structure. For the time being, lack of coordination in transport tariffs is a serious handicap to closer ties. Another issue is the fact that the partners often put obstacles to each other’s access to world markets by competing among themselves in deliveries of goods. They must learn to work together in meeting various challenges, to synchronize their decisions and try to implement them in the context of globalization of the world economy. This applies to harmonization of customs tariffs, proper mechanisms in order to protect national producers, antidumping investigations against “Eurasian” goods in Western markets and coordination of product pricing policies. All of this can turn the EurAsEC into an effective structure to be reckoned with throughout the universal economic system. In assessing the future prospects, we must also take into account the effect of such a geopolitical factor as the division of the post-Soviet space, especially Central Asia, into spheres of influence. Against the background of a worsening crisis in Afghanistan, the situation in Syria and an intensifying struggle against international terrorism, the USA, the EU countries, Pakistan, China, Israel, Iran and other countries concerned stepped up their activities in that region. The CIS republics have not remained on the sidelines either and apart from Russia, which has its own major interests in this area, a number of countries have been trying to strengthen their influence in the region, each having its own views on the development of the EurAsEC and on the possibility of drawing dividends from participation in the Community. The

Figure 3. The structure of Russian gas imports.

Figure 4. Gas exporters to Western Europe except from UK. Source: BP, BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2010.

creation of a common legal framework is also crucial and the EurAsEC partners have yet a long and difficult distance to cover in order to coordinate their national legislations, because there are still many fundamental differences in this area concerning economic activity. In this context, an important issue for the Community’s future is that of implementing multilateral decisions and understandings. The member countries will have to agree on a common set of rules and procedures for translating these into national decisions on the level of heads of state, government and parliament. The need to work out a common stand on accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) is of essential importance for the Community’s prospects. Russia, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have already joined that international organization while Belarus and Uzbekistan are potential participants in this process holding currently observer status. Uncoordinated steps to open up the markets of goods, capital and services to WTO countries could cause substantial damage to the economy of the other EurAsEC countries that’s why it is such important to accelerate the work being done to harmonize customs duties and the foreign trade regime in line with WTO standards. At the same time, the Community’s future will in large scale be determined by Russia’s policy, its desire to consolidate the partners’ efforts to deepen integration and build an effective interstate association in the interests of their socioeconomic development and security. Over the past few years, Russia’s policy in the post-Soviet region has been ever more constructive and pragmatic. Russian business is also turning into an essential factor of strengthening integration processes in the Commonwealth. Up to date it has mostly invested in the production, transportation, sale and processing of raw materials, but there are also plans for its participation in expanding telephone and telecommunications networks and engineering factories in the EurAsEC countries. There is also a trend towards more active involvement of Russian companies in the development of information technologies infrastructures and in servicing freight and passenger traffic. Moreover, while EU-Russian relations have remained static in the last decade, the same cannot be said of their respective relations with the countries in the “shared neighborhood”. Recently, Russia has been putting a premium on rule-based economic integration with robust institutional regimes. Moreover, EurAsEC is increasingly becoming popular among other nations. It is very recent the example of Israel’s request for accession to the union, a decision of critical geostrategic significance. Taking also into consideration the fact that Israel was a long life ally of the United States of America combined with the continuously decreasing American presence in the area of Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East due to its major economic problems, we come to the conclusion that Israel understands the signs of the times and embraces Russia in a historical turn following that of Egypt. It is, however, highly uncertain whether such a rapid pace of integration can be maintained so as to allow the projected creation of the Eurasian Economic Union by the target year 2015. Nevertheless, what has already been achieved provides a stable institutional basis for future completely structured economic integration and practice has shown that also from the view of geopolitics and developing globalization processes, the EurAsEC is an objective necessity and reality. As such it means that a viable form of economic integration has emerged in the post-Soviet region, in direct competition to that offered by the EU and has, moreover, moved Russia into rivalry with the EU in a domain in which the EU has not yet been challenged on the European continent. So the years to come will show us what the future holds for the union and what would be the economic and geostrategic effects of its existence.

References

- Henrekson, M., Torstenson, J. and Torstenson, R. (1997) Growth Effects of European Integration. European Economic Review, 41, 1537-1557. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(97)00063-9

- Shiells, C. and Sattar, S. (2004) The Low-Income Countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States. Progress and Challenges in Transition. International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, Washington DC.

- Michalopoulos, C. and Tarr, D. (1997) The Economics of Customs Unions in the Commonwealth of Independent States. Post Soviet Geography and Economics, 38.

- International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2013.

- Kononczuk, W. (2007) The Failure of Integration. The CIS and Other International Organisations in the Post-Soviet Area, 1991-2006, Centre for Eastern Studies, Warsaw, OSW Studies 2007-05-14.

- EDB Eurasian Integration Yearbook, 2013.

- Abalkina A. Preconditions and Prospects for Banking Integration in the Eurasian Economic Community.

- Krishna, P. (1998) Regionalism and Multilateralism: A Political Economy Approach. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113.

- Krugman, P. (1991) Is Bilateralism Bad? In: De Melo, J. and Panagariya, A., Eds., New Dimensions in Regional Integration, Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Rutherford, T. and Tarr, D. (2010) Regional Impacts of Liberalization of Barriers against Foreign Direct Investment in Services: The Case of Russia’s Accession to the WTO. Review of International Economics, 18, 30-46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9396.2009.00879.x

- Libman, A. and Vinokurov, E. (2012) Holding-Together Regionalism: Twenty Years of Post-Soviet Integration. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/9781137271136

- Averre, D. (2009) Competing Rationalities: Russia, the EU and the “Shared Neighbourhood”’. Europe-Asia Studies, 61, 1689-1713. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09668130903278918

- Dragneva, R. and Wolczuk, K. (2012) Russia, the Eurasian Customs Union and the EU: Cooperation, Stagnation or Rivalry? Chattam House Briefing Paper 2012/01, Chattam House, Russia and Eurasia Programme.

- Ferrero-Waldner, B. (2006) The European Neighbourhood Policy: The EU’s Newest Foreign Policy Instrument. European Foreign Affairs Review.

- Olcott, M.B., Aslund, A. and Garnett, S.W. (1999) Getting It Wrong: Regional Cooperation and the Commonwealth of Independent States. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington DC.

- Vinokurov, E. (2007) Russian Approaches to Integration in the Post-Soviet Space in the 2000s. In: Malfliet, K., Verpoest, L. and Vinokurov, E., Eds., The CIS, the EU, and Russia: Challenges of Integration, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

- Centre for Integration Studies (2012) Comprehensive Estimate of Macroeconomic Effect of Various Forms of Deep Economic Cooperation of Ukraine with members of the Customs Union and the CES. Saint-Petersburg.

- Van der Loo, G. and Van Elsuwege, P. (2012) Competing Paths of Regional Economic Integration in the Post-Soviet Space: Legal and Political Dilemmas for Ukraine. Review of Central and East European Law, 37, 421-447. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/092598812X13274154887060

- Riley, A. (2012) Commission v. Gazprom: The Antitrust Clash of the Decade? CEPS Policy Brief, CEPS, Brussels.

- BP (2010) BP Statistical Review of World Energy.