Psychology

Vol.06 No.01(2015), Article ID:53211,8 pages

10.4236/psych.2015.61004

Sex Differences in Homicidal Fantasies among Finnish University Students

Laura Auvinen-Lintunen1,2*, Helinä Häkkänen-Nyholm2, Tuula Ilonen3, Roope Tikkanen4

1Helsinki University Central Hospital, Helsinki, Finland

2Institute of Behavioural Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

3University of Turku, Turku, Finland

4Institute of Clinical Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

Email: *laura.auvinen-lintunen@hus.fi

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 18 November 2014; revised 4 December 2014; accepted 19 December 2014

ABSTRACT

Homicidal behavior is sex-linked. But research comparing male and female homicidal fantasies is sparse even though there is a potential link between fantasies and behavior. The aim of this study was to examine the frequency and contents of homicidal fantasies (targets, triggers, instruments, and emotional reactions) and their relation to substance abuse among 617 Finnish university stu- dents (mean age 24.2 years) contingent on gender. Sixty seven percent (n = 413) of respondents reported that they had experienced generally non-substance abuse-dependent homicidal fantasies during their lifetime. Males reported homicidal fantasies more frequently than females. Male fantasies involved the use of a weapon or tool and their fantasies frequently targeted a stranger, an acquaintance, or a public figure whereas female fantasies targeted intimate relationships such as family members or partners. Females reacted with negative emotions to their own homicidal fantasies but males lacked emotional response. Results suggest that homicidal fantasies are sex- linked.

Keywords:

Homicidal Fantasies, Sex Differences, Aggression, Emotional Reactions, University Students

1. Introduction

Human sex differences of homicidal behavior is a fairly well established field of research ( Jurik & Winn, 1990 ; Kellerman & Mercy, 1992 ; Pratt & Deosaransingh, 1997 ; Wilbanks, 1983 ), but information on a potential sex- link in homicidal fantasies among males and females is much more limited (Daly & Wilson 1988) . More specifically, previous research on homicidal fantasies have focused on the contents of the fantasies, situations in which they arise, triggers, the method of killing, or the real violent act associated with the homicidal fantasy (Crabb, 2000; Duntley, 2005; Grisso et al., 2000; Kenrick & Sheets, 1993) , especially in psychiatric patients (Grisso et al., 2000) , but not specifically between sexes, emotional reactions and in normal populations. Homicidal fantasies are considered a relatively normal phenomenon rooted in the evolutionary history of humans (Crabb, 2000) . According to the evolutionary perspective, homicidal fantasies represent one end of a continuum, the other end of which is actual homicides (Buss & Shackelford, 1997; Daly & Wilson, 1988) .

Numerous studies have found that men behave physically more aggressively than women ( Bettencourt & Miller, 1996 ; Eagly & Steffen, 1986 ; Frodi et al., 1977 ; Hyde, 1984 ; Knight et al., 1996 ; Maccoby & Jacklin, 1974, 1980 ) and men commit most homicides (Burbank, 1987; Buss & Shackelford, 1997; Fry, 1998; Daly & Wilson, 1988; Kellermann & Mercy, 1992) . Characteristic of the homicides committed by men is that the victim is a male stranger or acquaintances (not close relationship) ( Jurik & Winn, 1990 ; Kellerman & Mercy, 1992 ; Robbins et al., 2003 ), the motive is to defend one’s status or honor ( Buss & Shackelford, 1997 ; Polk, 1999 ), and jealousy (Buss & Shackelford, 1997; Daly & Wilson, 1988) , whereas homicides committed by women are usually directed towards other family members (close relationship), and their motive is most frequently self-de- fense (Campbell, 1993; Daly et al. 1982; Dobash et al., 1992; Jurik & Winn, 1990) . These features and differences are also present in Finnish homicides (Kivivuori et al., 2007; Weizmann-Henelius et al., 2003) , but homicides in Finland are usually committed under the influence of alcohol and tend to be rather impulsive acts of violence (manslaughters) than premeditated murders as compared with many other countries, which is a rationale to investigate particularly the characteristics of Finnish homicidal fantasies. Another difference appears in the instruments of homicides. Namely, the most frequent instrument of homicide in the United States is firearms (Gall & Lucas, 1996) and firearm violence has increased during last years (Hampy et al., 2014) whereas sharp instruments are used in Finland (Kivivuori et al., 2007) .

The reasons for sex differences in aggression have been explained, by biological predisposition (e.g., testosterone levels), social learning, reactions to provocation, patriarcal attitudes, sex roles, and types of aggression ( Bandura, 1973 ; Berkowitz, 1989 ; Archer, 1991 ; Baillargeon et al., 2007 ; Maccoby & Jacklin, 1974, 1980 ; Knight et al., 2002 ; Bettencourt & Miller, 1996 ). The sex differences in aggression have also been explained with evolutionary models, such as “sexual selection” and “differential male-female parental investment” (Daly & Wilson, 1988) . According to evolutionary psychology, men, in contrast to women, have faced different adaptive problems over human evolutionary history connected especially to the competition for a reproductive advantage (Buss, 1995) and therefore have developed different psychological mechanisms. Thus, males have inherited psychological mechanisms from their ancestors which are sensitive to situations or contexts where aggression has most likely led to a successful solution of a particular adaptive problem (Buss & Shackelford, 1997) .

Earlier research suggests that the emotional reactions on aggressive events are more subdued and positive among males than among females ( Bell & Forde, 1999 ; Graham & Wells, 2001 ; Lawrence, 2006 ). Negative emotions associated with aggression (e.g., guilt, anxiety, fear, and danger) experienced by females have been considered a preventive factor (Cross & Campbell, 2011: p. 392) .

We think it is reasonable to assume that there might be a positive correlation between actual homicides and homicidal fantasies. The 1993 study by Kenrick and Sheets has been considered to be the only systematic survey of homicidal fantasies in normal populations. They found that men report more homicidal fantasies than women. The fantasies of men were much more detailed and took longer time than women's homicidal fantasies. The situations featured in the homicidal fantasies differed significantly between sexes. For men, the situations related to work (“work disputes”), whereas for women the fantasies connected to internal family conflicts. Furthermore, men’s homicidal fantasies involved more situations relating to a personal threat, a robbery, a thrill (or stimulation seeking), quarrels about money, and public humiliation than those of the women. Men report using a greater variety of weapons in their fantasies compared to women (Kenrick & Sheets, 1993) . Crabb (2000) has suggested that the weapons that are represented in imagined homicides reflect those that are widely publicized in the mass media and are easily available.

The aim of our study was to examine the frequency and contents of homicidal fantasies (targets, triggers, instruments, and emotional reactions) and their relation to substance abuse contingent on gender. Based on previous research we hypothesized that males report homicidal fantasies more frequently than females and that male fantasies are targeted more often towards strangers, whereas women’s fantasies relate to closer relationships. We assumed that the triggers for homicidal fantasies in males would connect to jealousy, work, stimulus seeking, rivalry, and honor/face saving, whereas female triggers would be found in partnership problems and self-defence. Furthermore, we expected sharp instruments to be the weapon of choice in both males and females. Moreover, we assumed that alcohol and drugs would associate with homicidal fantasies. Finally, we expected that females would experience more negative emotions than men as a reaction to their homicidal fantasies.

2. Method

2.1. Sample and Sampling

The sample comprised students belonging to the Faculty of Arts, who were chosen randomly, and all of the psychology students in five different Finnish universities. The Faculty of Arts was chosen because it is one of the biggest and most heterogeneous faculties at the University of Helsinki. Participation was voluntary for all respondents. The electronic questionnaire and the covering letter were distributed through e-mail lists provided by student associations. In Finland, all university students automatically belong to an association, and distribut- ing information (on activities etc.) through an e-mail list is common practice. The study was approved by the ethical board of the Department of Psychology and the Information Technology Department of the University of Helsinki.

Altogether 626 university students responded to the questionnaire, of which 43.1% were psychology students. Removing nine participants from the analysis because of missing information left 617 participants. Of the respondents (n = 617), 85.9% were female, a percentage slightly higher than the general proportion of female students in the Faculty of Arts (76.5%) and the Departments of Psychology (80.1%) (Statistics Finland, 2005) . The average age of the respondents was 24.2 years (SD = 3.45, range 18 - 42 years), which is slightly lower than the average age of all Finnish university students (mean 29.2 years including postgraduate students) (Statistics Finland, 2005) .

2.2. Procedure

The electronic questionnaire asked inquired demographic variables of the respondents (age, sex, personal rela- tionships etc.). Questions on homicidal fantasies were formulated based on previous studies (Crabb, 2000; Kenrick & Sheets, 1993) . The definition of homicidal fantasies was given at the beginning of questionnaire: “by homicidal fantasy or thought is meant in this connection physical violence, such as hitting, pushing and killing”. The respondents were first asked, “Have you ever had homicidal fantasies?” If the answer was “yes” they were asked to continue to the next, more detailed questions concerning the frequency and timing of the fantasies, their objects and triggers, the use of a weapon in the fantasies and their emotional reactions to them. They were also asked whether their homicidal fantasies were usually targeted towards the same or a different person and whether they were experienced in the presence of that person. They were also asked whether they were under the influence of alcohol or drugs when experiencing homicidal fantasies. Almost every item involved several alternatives, which were later categorized into smaller groups for data analyses. The questions required “yes” or “no” responses, and a four-step Likert-type scale was used for questions about the reactions to the fantasies.

2.3. Data Analysis

Comparisons were performed with Chi-square and Man-Whitney U tests. Effect sizes were estimated as the phi (φ)-value. The significance level was set at p < .05. Data was analyzed using SPSS 16.0.

3. Results

3.1. Frequencies

In total, 66.9% (n = 413) of the total number of 617 respondents reported that they had experienced homicidal fantasies during their lifetime. Males reported having had homicidal fantasies more frequently than females (80.5% vs. 64.7% respectively, χ2= 8.369, p < .004). Nearly one in three of the males (27.9%) stated that their most recent fantasies occurred during the past week, while the corresponding figure in the females was 15.1% (χ2 = 5.830, p < .05). In general, however, the subjects reported having had homicidal fantasies quite seldom; 50.0% of the subjects (40.6% of the men, 51.9% of the women) reported that they had not had any homicidal fantasies during the last two months. Only a minority of the subjects (males 7.8% and females 5.3%) reported having had homicidal fantasies many times a week or even daily.

Other results not shown in the tables where that 66.1% of females living in an intimate relationship reported homicidal fantasies while the corresponding figure among males was 53.6% (χ2 = 3.868, p < .049), and that having children did not bear a significant association with homicidal fantasies.

3.2. Targets

Table 1 presents the targets of the homicidal fantasies with regard to the respondent’s sex. The target of male homicidal fantasies was a stranger, an acquaintance or a friend, and a public figure more frequently as compared with females. Females tended to have a family member or an ex-partner as the target of their homicidal fantasies more often than males (higher frequency and p-values approaching the significance level). The males homicidal fantasies contained a wider set of targets than females (68.7% vs. 53.4% respectively; χ2 (1) = 5.267, p = .022). Similarly, the females reported that their homicidal fantasies were directed towards the same person more frequently than males (29.1% vs. 11.9% respectively; χ2 (1) = 8.503, p = .004). Males reported that their homicidal fantasies appeared when the target was not present more often than the females (46.3% vs. 31.1% χ2 = 5.788, p = .016). Intimate relationships such as family members or partners/ex-partners, and the stalking persons, were the targets of female homicidal fantasies more often than among males.

3.3. Triggers

Table 2 presents the triggers for homicidal fantasies with regard to the respondent’s sex. The most frequent triggers reported by the males were “a desire for revenge” (44.3%), public humiliation (40.0%), or violence directing at himself (31.4%). The most frequently reported triggering factors among females were public humiliation (43.4%), quarrels (40.8%) and “a desire for revenge” (39.7%). Males had significantly more honor/face saving as triggers, whereas female triggers were quarrels, partnership problems, and undesired approach with moderate effect sizes. Triggers stimulation and to get financial benefit gave small trends pointing to higher prevalence among males, but their effect sizes were small due to small prevalence in our sample.

Table 1. Frequencies and comparison (males vs. females) of the targets of homicidal fantasies among 617 Finnish university students. Eighty percent (n = 70) of males (n tot. = 87) and 65% (n = 343) of females (n tot. = 530) had homicidal fantasies. Those subjects who experienced homicidal fantasies had two different target variables on average.

Notes: Family members include mother, father, step-father/mother, sister or brother, step sister/brother, other relatives, own child, and step-child. Friend/Acquintance includes friend, acquaintance, schoolfellow, and roommate. Work-related includes co-worker, employer, and customer.

Table 2. Frequencies and comparisons (males vs. females) of the triggers for homicidal fantasies among 617 Finnish university students. Eighty percent (n = 70) of males (n tot. = 87) and 65 % (n = 343) of females (n tot. = 530) had homicidal fantasies. Those subjects who experienced homicidal fantasies had three different trigger variables on average.

3.4. Instruments

Table 3 displays what weapon or a “method of killing” the homicidal fantasies contained. Of the respondents who reported homicidal fantasies (n = 413) 98 (23.7%) reported that their fantasies involved some kind of weapon or tool. The homicidal fantasies of the men (44.1%, n = 30) involved the use of a weapon or tool much more frequently than those of the women (19.9%, n = 68) (χ2 (1) = 18.315, p < .000). The two most frequent instruments among males were firearms and sharp instruments whereas the top-two instruments among females were sharp instruments and blunt weapons.

3.5. Emotional Reactions

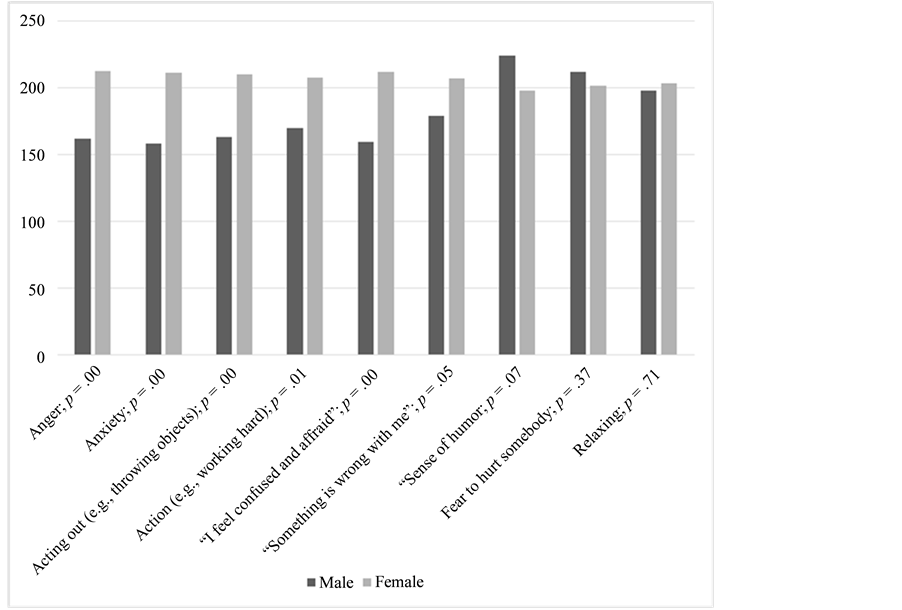

Females and males emotional reactions to the homicidal fantasies differed in several ways. Females reported stronger negative emotions (anger, anxiety, acting out, and action) than males. Males tended to react with a sense of humor more than females (comparison approached the significance level). The results are presented in Figure 1.

3.6. Alcohol and Drugs

Only 25.4% of the subjects reported that their fantasies arose when they were under the influence of alcohol. This bore no significant association with the respondent’s sex.

4. Discussion

The aim of our study was to examine sex differences in homicidal fantasies among Finnish university students. In general, the results complied with the results of earlier studies (Kenrick & Sheets, 1993; Crabb, 2000) and didn’t offer big surprises. As hypothesized, males reported homicidal fantasies more frequently than females and male fantasies were targeted more often towards strangers, whereas female fantasies connected to closer rela- tionships. In accordance to our assumptions, the triggers for homicidal fantasies in males connected to honor/ face saving, whereas female triggers were anchored in partnership problems and self-defence. Triggers stimuli-

Table 3. Frequencies and comparisons (males vs. females) of the instruments in homicidal fantasies among 617 Finnish university students. Of the respondents who reported homicidal fantasies (n = 413) forty percent (n = 30) of males and twenty percent of females (n = 68) (n tot. = 98, 23.7%) reported that their fantasies involved some kind of weapon or tool involving two different instrument variables on average.

Figure 1. Emotional reactions on homicidal fantasies among 617 Finnish university students. Two out of three subjects experienced homicidal fantasies. Comparisons between males vs. females were performed with the Mann-Whitney U-test; MD Mean Rank-scores are shown on the y-axis and emotional reactions and p-values are shown on the x-axis.

tion and to get financial benefit gave small trends pointing to higher prevalence among males, but their effect sizes were small due to small prevalence in our sample. Jealousy, however, failed to show any association with sex and was also a rare trigger. We expected sharp instruments to be the weapon of choice in both males and females, but results confirmed this only in females. Males frequently thought of killing someone with a firearm, which is a rear instrument among the actual homicides in Finland probably due to that firearms are strictly regulated and are not usually available in impulsive homicides (the majority of Finnish homicides are impulsive manslaughters). Moreover, we assumed that alcohol and drugs would associate with homicidal fantasies, but results showed otherwise; even though many studies have found that alcohol predisposes people to engage in aggressive behavior, we could not demonstrate a corresponding relation between alcohol and homicidal fantasies. A possible explanation for this would be that small amounts of alcohol (assumingly heavy substance abuse in not prevalent among university students) have an anxiolytic effect and represses aggressive thoughts while heavy drinking may trigger actual impulsive violence. Finally, we expected that females would experience more negative emotions than men as a reaction to their homicidal fantasies, which was confirmed by the results. Negative emotions probably function as a preventive factor against actual violent behavior.

In our study, contrary to earlier studies, spouses were quite infrequently the targets of homicidal fantasies, and no significant sex effects were seen for this variable. However, relatively few of the university students were involved in a steady relationship, which may partly explain the results.

One interesting result was that men’s homicidal fantasies were targeted much more frequently than women towards public figures. This sex difference seems to be consistent with the evolutionary perspective that men compete with each other for status and a reputation in society, outside of their homes. According to a study by Kenrick and Sheets (1993) , men reported having had more homicidal fantasies than women about the leader of their country.

The meaningful difference between sexes concerning the honor/face saving-trigger agrees with the statement that women are rarely involved in honor contest violence (Polk, 1994) . According to Daly and Wilson (1988) “honor contest violence can be seen as a form of competition strategy among males”.

Compared with earlier results (Kenrick & Sheets 1993; Crabb, 2000) , a smaller percentage of Finnish uni- versity students reported using a weapon in their homicidal fantasies. In our study, only 23.7% of those with homicidal fantasies had fantasies that included a weapon, while the corresponding percentage in Kenrick and Sheets’ (1993) study was 87%, 93% for men (in our study 44.1% for the men) and 75% for women (in our study only 19.9% for the women). These differences may be able to be explained through cultural differences, e.g. in 23% of Finnish homicides, death was caused by battering or strangling the victim with bare hands or feet, without any weapon being used (Kivivuori et al., 2007: p. 8) .

Why do women report fewer homicidal fantasies than men? Is it difficult for women to express their aggres- sion even on the imagined level, or is aggression simply expressed indirectly, following culture and stereotypical sex roles? Perhaps one reason for this is a social desirability, in other words, women tend to dress up their homicidal fantasies. We found that women reported more negative emotions than men as a reaction to their homicidal fantasies. These negative feelings may also decrease women’s willingness to report them, which could bias the results of our paper. According to our results, women tend to suppress their homicidal fantasies. This may confirm the evolutionary theory that directly expressing aggression is more dangerous for women than men, not only in relation to actual behaviour, but also on the level of fantasy.

A limitation of our study was several potential sources of bias; we used retrospective self-reports in which memory distortions may occur and an electronic questionnaire that didn’t allow us to estimate the response rate since it is impossible to identify how many people read the e-mail. Moreover, the concepts of “homicide” and “homicidal fantasies” are very sensitive and difficult subjects for most of us; consequently the respondents may not have wanted to tell the truth about their homicidal fantasies, although it was stated at the beginning of the questionnaire that they are common to everyone.

Conclusively, we judge that our results on the specific contents of the sex-linked homicidal fantasies among Finnish university students lay ground for mapping the contents of homicidal fantasies in other normal popula- tions and selected samples such as psychopaths, as well. We hope that our results would inspire other research groups to examine the causal effect of specific sex-linked homicidal fantasies on actual violence in prospective settings.

Acknowledgements

The second author would like to thank the Academy of Finland (personal Grants No. 75697 and No. 211176) for the financial support.

All authors reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interests in the publication of this work.

References

- Archer, J. (1991). The Influence of Testosterone on Human Aggression. British Journal of Psychology, 82, 1-28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1991.tb02379.x

- Baillargeon, R. H, Zoccolillo, M., Keenan, K., Cote, S., Perusse, D., Wu, H.-X., Boivin, M., & Tremblay, R. E. (2007). Sex Differences in Physical Aggression: A Prospective Population-Based Survey of Children before and after 2 Years of Age. Developmental Psychology, 43, 13-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.13

- Bandura, A. (1973). Aggression: A Social Learning Analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Bell, M. L., & Forde, D. R. (1999). A Factorial Survey of Interpersonal Conflict Resolution. The Journal of Social Psychology, 139, 369-377. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00224549909598392

- Berkowitz, L. (1989). Frustration-Aggression Hypothesis: Examination and Reformulation. Psychological Bulletin, 106, 59- 73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.106.1.59

- Bettencourt, B. A., & Miller, N. (1996). Sex differences in Aggression as a Function of Provocation: A Meta-Analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 422-447. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.422

- Burbank, V. K. (1987). Female Aggression in Cross-Cultural Perspective. Behavior Science Research, 21, 70-100.

- Buss, D. M. (1995). Psychological Sex Differences: Origins through Sexual Selection. American Psychologist, 50, 164-168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.50.3.164

- Buss, D. M., & Shackelford, T. K. (1997). Human Aggression in Evolutionary Psychological Perspective. Clinical Psychology Review, 17, 605-619. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(97)00037-8

- Campbell, A. (1993). Men, Women, and Aggression. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Crabb, P. B. (2000). The Material Culture of Homicidal Fantasies. Aggressive Behaviour, 26, 225-234. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(2000)26:3<225::AID-AB2>3.0.CO;2-R

- Cross, C. P., & Campbell, A. (2011). Women’s Aggression. Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 16, 390-398. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2011.02.012

- Daly, M., & Wilson, M. (1988). Homicide. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

- Daly, M., Wilson, M., & Weghorst, S. J. (1982). Male Sexual Jealousy. Ethology and Sociobiology, 3, 11-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0162-3095(82)90027-9

- Dobash, R. B., Dobash, R. E., Wilson, M., & Daily, M. (1992). The Myth of Sexual Symmetry in Marital Violence. Social Problems, 39, 71-91.

- Duntley, J. D. (2005). Homicidal Ideations. Dissertation, Austin, TX: The University of Texas at Austin.

- Eagly, A. H., & Steffen, V. J. (1986). Sex and Aggressive Behaviour: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Social Psychological Literature. Psychological Bulletin, 100, 309-330. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.100.3.309

- Frodi, A., Macaulay, J., & Thome, P. R. (1977). Are Women Always Less Aggressive than Men? A Review of the Experimental Literature. Psychological Bulletin, 84, 634-660. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.84.4.634

- Fry, D. P. (1998). Anthropological Perspectives on Aggression: Sex Differences and Cultural Variation. Aggressive Behaviour, 24, 81-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1998)24:2<81::AID-AB1>3.0.CO;2-V

- Gall, T. L., & Lucas, D. M. (1996). Statistics on Weapons and Violence. Detroit, MI: Gale Research.

- Graham, K., & Wells, S. (2001). The Two Worlds of Aggression for Men and Women. Sex Roles, 45, 595-622. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1014811624944

- Grisso, T., Davis, J., Vesselinov, R., Appelbaum, P. S., & Monahan, J. (2000). Violent Thoughts and Violent Behaviour Following Hospitalization for Mental Disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 388-398. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.388

- Hampy, S., McDonald, R., & Grych, J. (2014). Trends in Violence Research: An Update through 2013. Psychology of Violence, 4, 1-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0035384

- Hyde, J. S. (1984). How Large Are Sex Differences in Aggression? A Developmental Meta-Analysis. Developmental Psychology, 20, 722-736. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.20.4.722

- Jurik, N. C., & Winn, R. (1990). Sex and Homicide: A Comparison of Men and Women Who Kill. Violence and Victims, 5, 227-242.

- Kellermann, A. L., & Mercy, J. A. (1992). Men, Women, and Murder: Gender-Specific Differences in Rates of Fatal Vio- lence and Victimization. The Journal of Trauma, 33, 1-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005373-199207000-00001

- Kenrick, D. T., & Sheets, V. (1993). Homicidal Fantasies. Ethology and Sociobiology, 14, 231-246. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0162-3095(93)90019-E

- Kivivuori , J., Lehti, M., & Aaltonen, M. (2007). Homicide in Finland, 2002-2006. Helsinki: NRILP.

- Knight, G. P., Fabes, R. A., & Higgins, D. A. (1996). Concerns about Drawing Causal Inferences from Meta-Analyses: An Example in the Study of Sex Differences in Aggression. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 410-421. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.410

- Knight, G. P., Guthrie, I. K., Page, M. C., & Fabes, R. A. (2002). Emotional Arousal and Sex Differences in Aggression: A Meta-Analysis. Aggressive Behavior, 28, 366-393. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ab.80011

- Lawrence, C. (2006). Measuring Individual Responses to Aggression-Triggering Events: The Development of the Situational Triggers of Aggressive Responses (STAR) Scale. Aggressive Behavior, 32, 241-252. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ab.20122

- Maccoby, E. E., & Jacklin, C. N. (1974). The Psychology of Sex Differences. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Maccoby, E. E., & Jacklin, C. N. (1980). Sex Differences in Aggression: A Rejoinder and Reprise. Child Development, 51, 964-980. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1129535

- Polk, K. (1994). When Men Kill: Scenarios of Masculine Violence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Polk, K. (1999). Males and Honor Contest Violence. Homicide Studies, 3, 6-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.410

- Pratt, C., & Deosaransingh, K. (1997). Sex Differences in Homicide in Contra Costa County, California: 1982-1993. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 13, 19-24.

- Robbins, P. C., Monahan, J., & Silver, E. (2003). Mental Disorder, Violence and Gender. Law and Human Behaviour, 27, 561-571. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:LAHU.0000004886.13268.f2

- Statistics Finland (2005). University Education 2005. Helsinki: Statistics Finland.

- Weizmann-Henelius, G., Viemerö, V., & Eronen, M. (2003). The Violent Female Perpetrator and Her Victim. Forensic Science International, 133, 197-203. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0379-0738(03)00068-9

- Wilbanks, W. (1983). The Female Homicide Offender in Dade Country, Florida. Criminal Justice Review, 8, 9-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/073401688300800203

NOTES

*Corresponding author.