Journal of Environmental Protection

Vol.3 No.11(2012), Article ID:24726,12 pages DOI:10.4236/jep.2012.311163

Developing a Social Business Model for Zero Waste Management Systems: A Case Study Analysis

![]()

Zero Waste SA Research Centre for Sustainable Design and Behaviour (sd + b), School of Art, Architecture and Design, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia.

Email: zamau001@mymail.unisa.edu.au

Received September 13th, 2012; revised October 9th, 2012; accepted November 7th, 2012

Keywords: Reuse; Recycling; Waste Business; Extended Producer Responsibility; Social Enterprise; Social Business

ABSTRACT

The global gross domestic product (GDP) has increased by 40% during 1960-2000; poverty and inequity have also increased over the same time [1]. Many social scientists and economists have indicted the existing monetary-based corporate social structures with their insignificant contribution to the problem solving and social development processes. Waste is one of the major problems in every city around the globe. This study explores policy instruments in existing profit maximizing business systems and proposes an alternative business approach for the zero waste management systems. The paper proposes a conceptualized social business model for waste management systems based on a case study of two different organizations working in waste management systems in low and high consuming cities. “Waste Concern”, on one hand, is a social business enterprise, promoting waste recycling activities through the community-based decentralized composting technology using public-private community partnerships model in a low consuming city i.e. Dhaka. “Finding Workable Solutions”, on the other hand, is a non-profit organization that rehabilitates and empowers disabled peoples in high consuming city, i.e. Adelaide by collecting and transforming sellable household waste. This paper argues that waste management social business would be an opportunity for the corporate world to implement the strategy of extended producer responsibility in more successful way. Under this business model, producers can contribute more significantly in the social development process, promote value creation, ensure product stewardship and equity within the society. In addition, the conceptualized waste management social business model will endorse closed-loop resource flow in the society and will maximize resource utilization through recycling, reusing and re-gifting in the circular society.

1. Introduction

The current consumption-driven lifestyle in the high consuming world is environmentally damaging [2] and increasing inequity in society due to the disproportionate utilization of ecological systems [3]. On one hand, increasing utilization and depletion of natural resources in high consuming cities such as Adelaide, endorses inequity in the society and copying of the current trend of western lifestyle and consumption pattern by the huge number of people from low consuming cities such as Dhaka on the other, increases the fear of indeterminate future of the world.

Many cities in the high consuming world, Adelaide for instance, are trying to be a “zero waste city” [4] by achieving 100% recycling and resource recovery of municipal solid waste. However, it is hard to achieve zero waste goals without proper management policies in place. A 100% recycling may not necessarily achieve the zero waste goal because of the key principles of zero waste goal is firstly, to prevention (through design, behaviour change) of unwanted waste at the first place, secondly to re-use functional waste material (through redistribution or consumptive behaviour) and thirdly, to recover all resources from the waste streams (through advance resource recovery facilities). Recycling is the very first step to approach the zero waste goals. The study examines whether an alternative business model can be an effective instrument for the local authority to promote the zero waste goal. Therefore, the paper would primarily be interested to discuss whether or not a social business model can be a useful tool to increase the waste prevention, reuse and recycling efficiency in current waste management systems.

Among different policy instruments, green business policy is one of the most important economic tools to achieve economic and environmental sustainability. There are different business models available which embrace core business values including social, economic, technological and environmental. Over the years, business models have transformed from single economic value chains to multiple value chains including social and environmental values in the core business manifesto.

Green marketing has flourished since the late 1990s where consumers chose to buy products or not based upon the environmental considerations of the design, production, packaging, use and disposal of the products [5]. The concept of corporate social responsibility [6-8] has emerged to respond to environmental issues in a more accountable manner by businesses. However, participation by the small and medium enterprises (SME) in corporate social responsibility issues has been found to be lacking [7].

There are various aspects involved in green business and marketing policy, such as equitable profit distribution thorough fair-trade, green-label or eco-label [9-12]. However, all of these initiatives have received much criticism due to poor performance and not contributing significantly in establishing equity in the society [13-16].

The global environmental business market is rapidly flourishing. The market volume for environmental technologies, mainly comprising products and services amounted to approximately $1370 billion in 2008, according to Germany-based Roland Berger, the Strategy Consultant, with a projected $2740 billion by 2020 [17]. Of this, the share of waste management and recycling is estimated at $41 billion in 2008, $63 billion by 2020 and the global waste-to-energy to reach $28.8 billion by 2015 [18]. Surprisingly, most of the business model working in the area of environmental management is either profit-maximizing organizations or non-profit organizations which mainly rely on charity or subsidy.

Both profit-maximizing organizations and non-profit organizations have certain limitations and conflicts of interest when it comes to social or environmental benefits. Because profit maximizing organizations are primarily focused on the profit or economic benefit rather than social welfare; on the other hand, NGOs depend on the funding body to execute beneficial activities to the society. Thus, an alternate business model is studied in this paper to solve the common social problem in economic and environmentally sound manner. Social Business (SB) can be an alternative business model for solving social problems because it is not based on charity. It is a business in every sense. SB has to recover it full cost while achieving its social objective [19].

By recognizing “waste” as a social problem as well as a resource, the concept of how the social business model can be a helpful business model to eradicate “waste problem” from our society and recover resources for further use are primary focuses of this paper. The aims of this study are to understand existing business trends and to develop a conceptualized social business model for zero waste management systems based on the lessons learnt from a case study analysis of two social enterprises. The case study is done to explore barriers and opportunities for establishing a new business model in the context of socio-economic and environmental development. The case study of two different enterprises analyses the process of experimentation [20] and learning a “discovery driven” approach [21] to overcome the existing barriers in the development of new business model.

“Waste Concern” on one hand, a social business enterprise, is promoting waste recycling activities through the community based decentralized composting technology using public-private-community partnerships model in low consuming city i.e. Dhaka. “Finding Workable Solutions” on the other hand, a non-profit organization, rehabilitates and empowers disabled peoples in high consuming city i.e. Adelaide by collecting and transforming sellable household waste. Thus the study analyses two different waste management business enterprises working in contrasting business contexts.

2. Material and Method

2.1. For-Profit vs Not-for-Profit Business

In a profit maximizing business, including small and medium enterprises or large firms, the owner or the investor is the key beneficiary of the company. However, in a social business enterprise, profit is non-dividend. Therefore, characteristics of the social business are different from the current style of profit maximizing business. However, it is essential to understand and cope with the traditional business practices for introducing a new business model like the social business model.

There are different types of businesses available with various business objectives. There are five broad objecttives [22] observed in current business practice: social, economic, human, national and the global objectives. Therefore, business objectives include profit maximizing, benefit of the society, human wellbeing and development, national goals and global benefits as core business objectives.

For-profit business is generally characterized as the business owned and operated independently. Owners contribute most of the investment and therefore, the main decision-making functions rest with the owners [23]. In traditional business, venture is driven by three forces: owner or entrepreneur, resources and opportunity [24].

Not-for-profit or simply non-profit enterprise is generally known as a “social enterprise”. The “Social Entrepreneurship” (SE) creates new model for the provision of products and services that cater directly to basic human needs that remain unsatisfied by current economic or social institutions [25]. In addition, social entrepreneurship combines the resourcefulness of traditional entrepreneurship with a mission to change society [25]. However, SE is primarily based on charity or donor funds. In both for-profit and non-profit business organizations, economic benefits and social objectives are not practiced in a balanced way. Thus an alternative business model is needed to explore and implement methods of delivering economic, social and environmental benefits.

2.2. Social Business Model

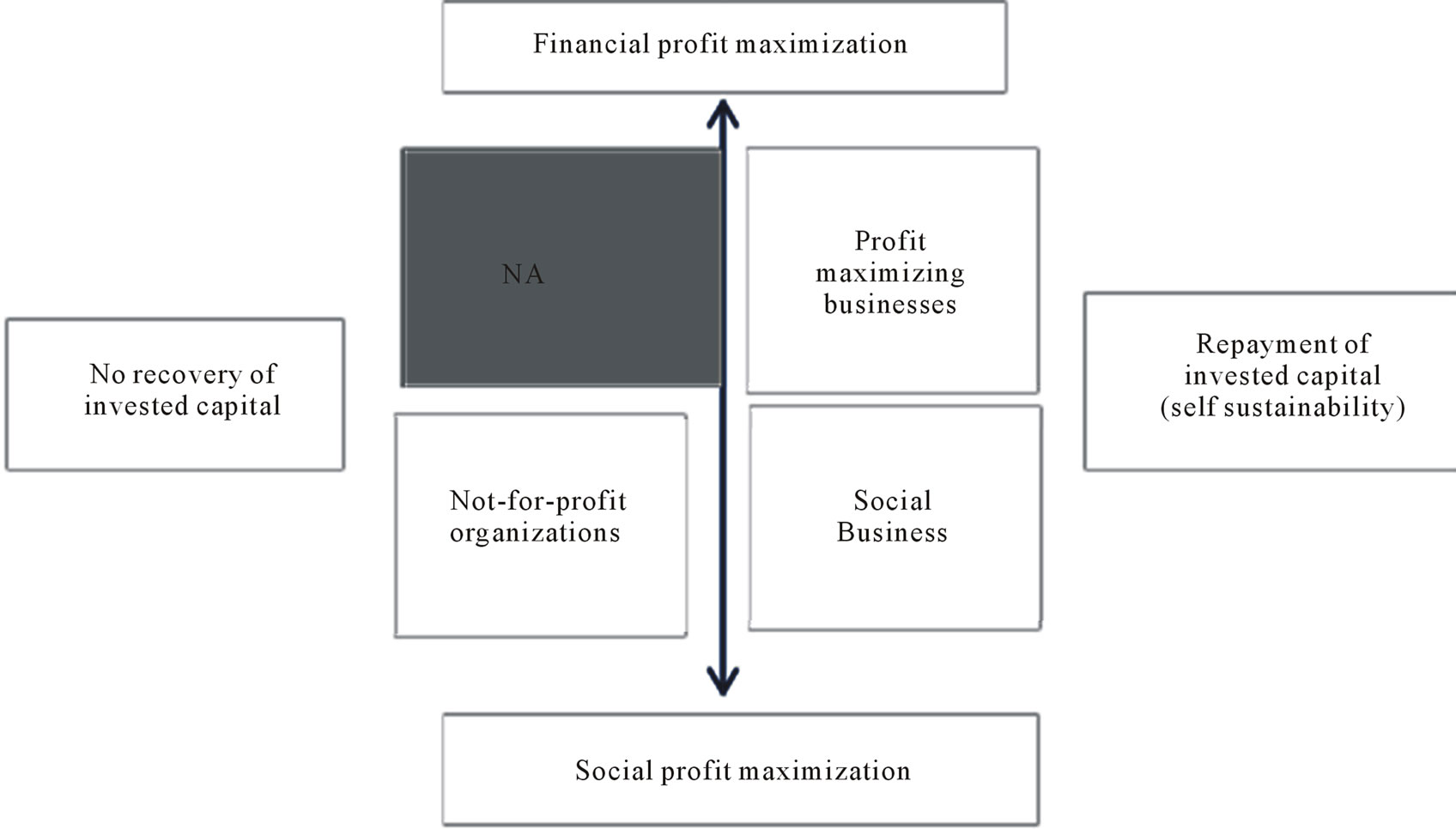

The concept of social business is an emerging business concept. The concept was first proposed by the Nobel Peace Prize laureate Professor Muhammad Yunus in his book “Creating a World without Poverty”. According to Yunus, social business is a “very specific type of business—a non-loss, non-dividend company with a social objective” [26]. Therefore, social business is designed and operated as a business enterprise, with products, services, customers, market, expenses and revenues but with the profit-maximization principle replaced by the social-benefit principle [19]. Figure 1 shows the comparative structure of different types of business.

The principles of social business include social welfare, financial and economic stability, environmental benefit, company profit, ensuring joy while working with the aim of the social development [28]. Therefore, social business model not only focuses on the social welfare and economic benefit but also on the environmental advantage. Therefore, a holistic social business model includes tripled bottom line (also known as people, planet, profit or the three pillars) for balancing traditional economic goals with social and environmental concerns [29].

3. Literature Review

The Brundtland Report “Our Common Future” [30] brought the concept of sustainable development into the mainstream of business and political thought however, win-win outcomes seem unlike although the corporate environmental or sustainability strategies are becoming commonplace in the current for-profit business arena, they are not contributing significant global impact in regards to sustainability [31].

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) was an innovative tool for the corporate business market to contribute to society and at the same time work as a value adding mechanism to the consumers. Therefore, CSR is increaseingly seen as an imperative for sustainable business and there is a growing literature on the effect of CSR on corporate reputation [32]. However, the effect of CSR on business performance is varies widely [33] and most recently some start to believe that CSR, as a business, governance and ethics system, has failed [34]. Moving from the ages of greed, philanthropy, marketing and management using charitable, promotional and strategic CSR approaches to the radical CSR using creativity, scalability, responsiveness, “glocality” and circularity is essential [34].

The futurist designer and philosopher Jacque Fresco coined the concept of a resource-based global economy where national boundaries will be made by realizing the declaration of the world’s resources as being the common heritage of all people [35]. The root cause of current problems in the monetary-based economy is the dominance of “Modern Money Mechanics” which creates structural classism and inequity in society. Although

Figure 1. Social business vs. profit maximizing business and not-for-profit organizations [27].

global gross domestic product (GDP) has increased by 40% from 1960 to 2000, poverty also increased by 17% over the same period [1]. Existing profit maximizing business has been significantly increasing social inequity due to undistributed access to global resources.

Concerns about corporate influence on democracy, the growing disparity in wealth and the absence of legal repercussions following the recent global financial crisis [36] are growing and manifesting as protest movements such as “Occupy Wall Street” in New York and similar in many other cities around the world. The demonstrations claim that 99% of the population are suffering at the hands of the 1%; there should be more and better jobs, more equal distribution of income, bank reform, a reducetion of the influence of corporations on politics, and equitable distribution of benefits [37].

From Thomas Kuhn’s work, step-change only happens when we can re-perceive our world, when we can find a genuinely new paradigm or pattern of thinking [34]. Therefore, a new paradigm of this existing corporate world is urgently needed. The social business model is one of the new paradigms though which we can shrink the gap between corporate and civil society, through which we can establish equity in society.

A number of studies [38-43] have already been done to elucidate different business models and their purposes in social and global value creation in addition to economic benefit. Darby and Jenkins [44] study of the company Wastesavers in the United Kingdom, proposed the integration of sustainability indicators to the social enterprise business model. Wastesavers is a social enterprise that comprises of a charity and a not-for-profit business to establish, operate and develop a variety of community recycling services for the collection and sale of postconsumer wastes to:

• promote the environmental value of recycling, reduction and minimisation of waste.

• involve unemployed, volunteers and people with special needs in recycling services.

• encourage and assist in the development of other initiatives elsewhere in the United Kingdom.

Another related study, by Seelos & Mair [25] and explained social entrepreneurship as a business model to serve the poor. The studies were based on the case study of three social business enterprises founded for social development goals. Even though SE is established by the charity, social entrepreneurship may also encourage established corporations to take on greater social responsebility.

A social business model can be developed and implemented for almost all types of business that serve certain social benefits. From micro-credit finance to the giant mega-port all can be a social business [19]. The present trend of social enterprise is based on charity. This is not always the answer because hand-outs may encourage dependence rather than self-help and self-confidence [19].

One of the most important and relevant studies in social business has been done by Yunus et al. [27] based on the experiences of Grameen (creator of the micro-credit concept) organizations in Bangladesh. In the study, authors proposed a paradigm shift of the conventional charity based social enterprise to a new business model called a self-sufficient social business (SB) model. One such example is “Grameen Danone” launched in 2006 and the first social business enterprises in the world to provide children with many of the key nutrients that are typically missing from their diet in rural Bangladesh. It is run on a “no loss, no dividend” basis [19]. The Adidas venture is the latest example of a social business model making shoes for as little as US$1 for Bangladeshis, particularly children who are exposed to skin-borne diseases [45]. The SB concept has been successfully implementing and promoting in poverty the reduction of poverty, the eradication of malnutrition and improvement of healthcare in Bangladesh.

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) is a concept where the producers of consumer goods are required to take greater responsibility for managing the environmental impact of their products throughout their entire life cycle [46]. In the existing waste management practices, producers have the limited access in the waste recycling and take back programmes. Social business can be an integral part of the producer in the role of product stewardship. Therefore, the SB is undoubtedly an important paradigm shift and urgent needed for mainstream business practices. Therefore, this article aims to replicate the social business model for solving a social problem such as the waste problem in our society.

It is evident from the literature review that there is no such business model available at this moment that operates under the social business model to solve the “waste” problem from our society. As most of the waste management experts are aware of the technological and socio-economic advancement in waste management system therefore, this paper tries to understand the business model in different perspective. Rather than looking through a traditional profit maximizing business model this paper primarily focuses on the alternative waste management business model such as social business model.

4. Case Study Analysis

4.1. Case of Finding Workable Solutions in Australia

Finding Workable Solutions (FWS) Inc. is a non-profit organization and predominantly based on Commonwealth funds providing assistance to job seekers with a disadvantage or disability in South Australia. FWS’s vision is to responds to the needs of disadvantaged people in communities by providing innovative and flexible services complying with social and environmental sustainability. FWS was established in 1989 and has provided employment and vocational training since then to the disabled people.

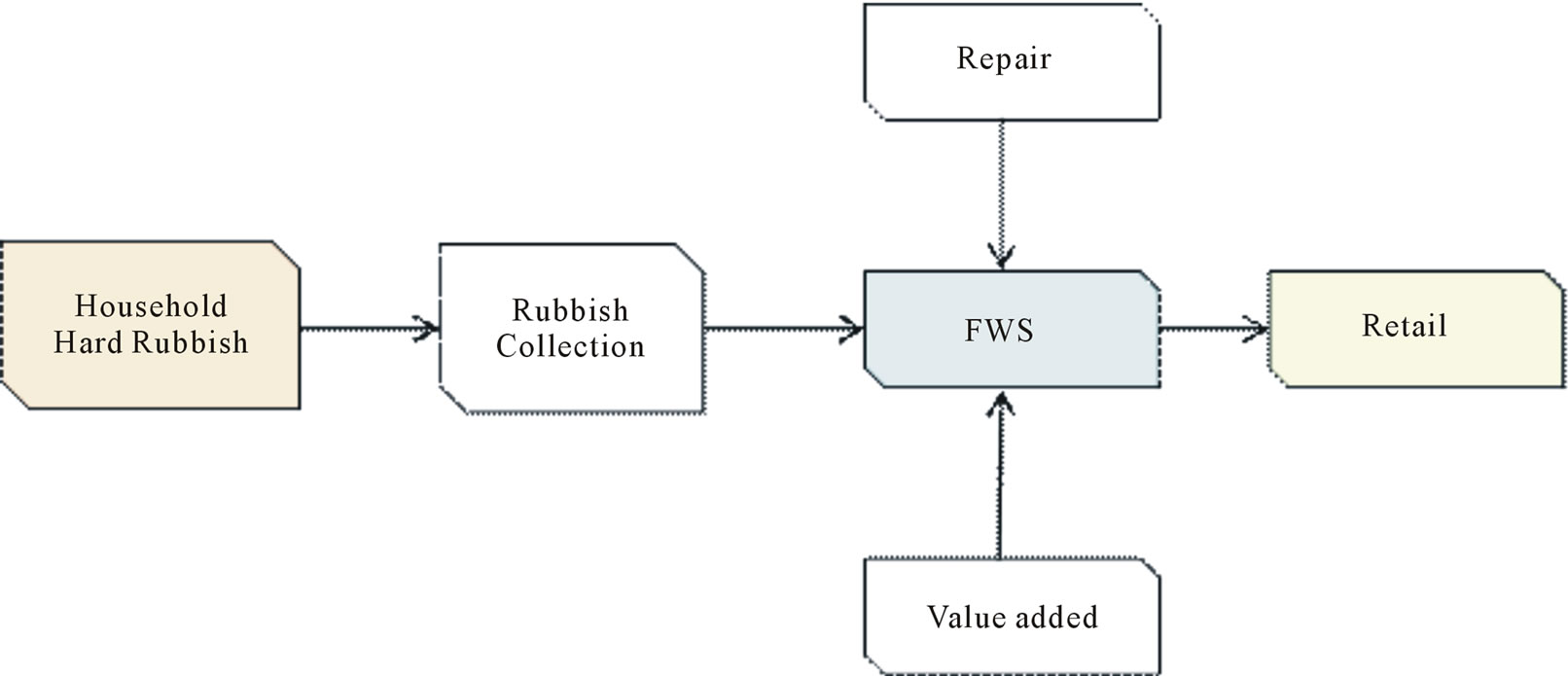

FWS collects economically valuable hard waste such as furniture, electronic items etc. which can be repaired, reused and re-sold to the community. From 2004 to 2010, a total number of 1130 clients have been supported in the whole business process of hard waste collection, repair and retail and the organization has increased from 23 full time employees in 2004 to 68 in 2010.

Collection of hard waste is basically done on a voluntary basis by phone call or drop-off system. FWS pick-up the waste which has potential sells and reuse values. If the collected waste requires repair such as minor fixing or painting then the vocational employees, mostly disabled, complete the repairs and make the items more functional and economically valuable for selling.

It is evident from the FWS’s business model that a significant volume of waste flow is reduced by the reusing after minor repair. However, there is no such guarantee for the user satisfaction on second-hand goods. Since the repair experts have the basic vocational training on repairmen of goods therefore, it is assumed that the elective goods are safe to use. The study acknowledges that this is not the unique business model in selling second hand goods (there are many examples available in Europe, Asia or in USA) but significantly different from the other business organization in the context of profit maximization and business orientation.

Since, FWS is a non-profit organization; it has tax exempt status under Section 23 (e) of the Australian Income Tax Assessment Act 1939. Total sales revenue has increased from $194,086 in 2004 to $690,638 in 2010 and total income has increased from$1,584,828 in 2004 to $7,124,860 in 2010 with an increment of 5% of the net asset. Figure 2 shows the resource flow in the business model of FWS, where,

• Hard rubbish or economically valuable and functional waste is collected from households.

• FWS adds value to the collected goods through repair or renovation.

• The goods are sold.

Even though FWS is a non-profit organization, it creates money out of garbage materials, provides jobs to many disabled people and contributes to build a more promising society. FWS is collecting reusable and sellable products, giving them longer life spans and circulating them within the society. By circulating the goods again and again, FWS contributes to the global environmental improvement and decreasing the depletion of the global resources.

4.2. Case of Waste Concern in Bangladesh

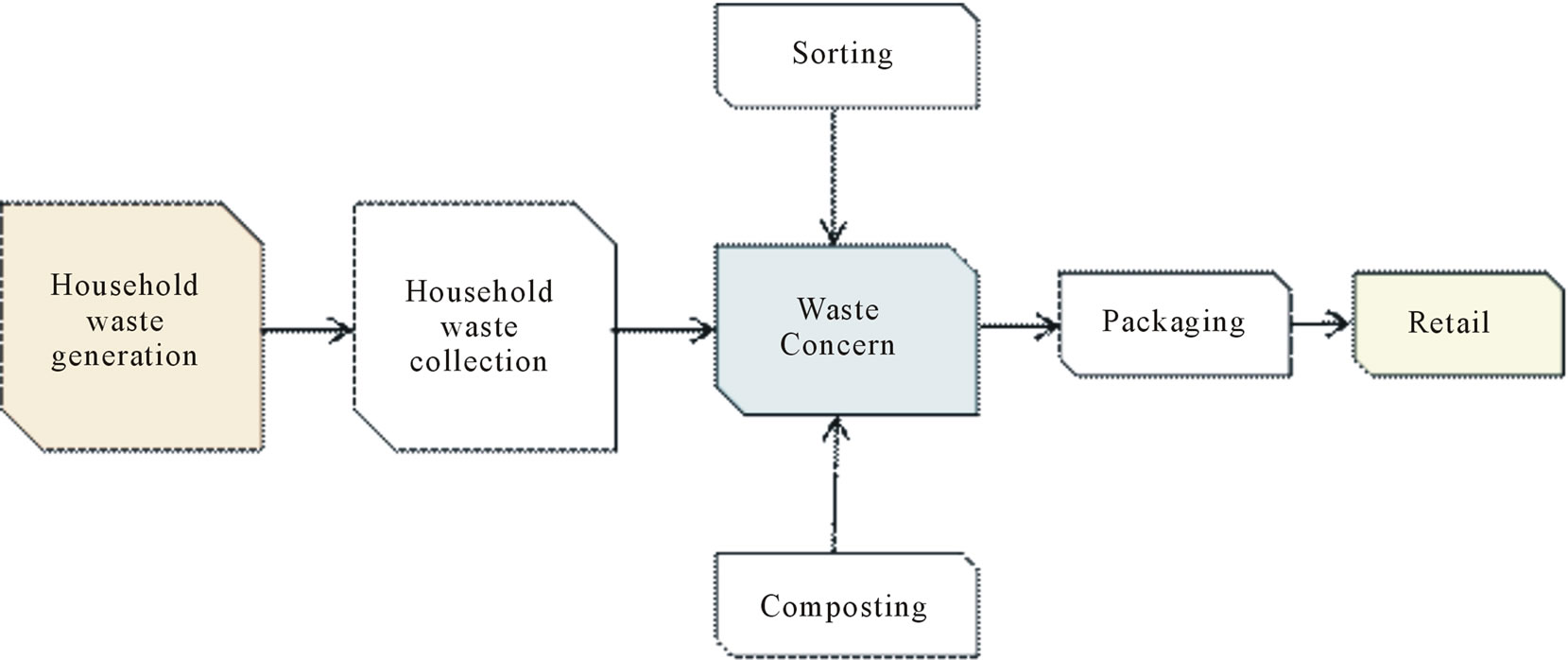

Waste Concern (WC) a “not-for-profit” social business enterprise was founded in 1995 in Dhaka, Bangladesh with the motto “waste is a resource”. Over the time of the business is expansion, Waste Concern Group was formed and which has now both for-profit and not-for-profit enterprises. WC primarily deals with a specific waste stream such as organic waste of the daily household waste. As more than 70 per cent of municipal solid waste in Dhaka is biodegradable (organic), therefore, WC is primarily interested in improving waste management systems as well as socio-economic and environmental benefits by recycling organic waste and organic waste is composted and sold as bio-rich fertilizer.

Organic wastes are collected by community based waste collection systems where household dwellers pay to have their waste collected. WC’s collection vans then bring organic waste to the composting plant. WC serves the communities partially in Dhaka with its five com-

Figure 2. Resource flow in FWS’s business model.

posting plants of a total 20 tons/day (one 10 - 12 ton/day, two 3 ton/day and one 1 ton/day). Figure 3 shows the resources flow in business model of WC where, household waste are collected by community collection systems, collected waste are then transported to WC’s composting plant, organic wastes are sorted out and processed for composting. Finally, the composted organic fertilizers are sent for retail to the local farmer.

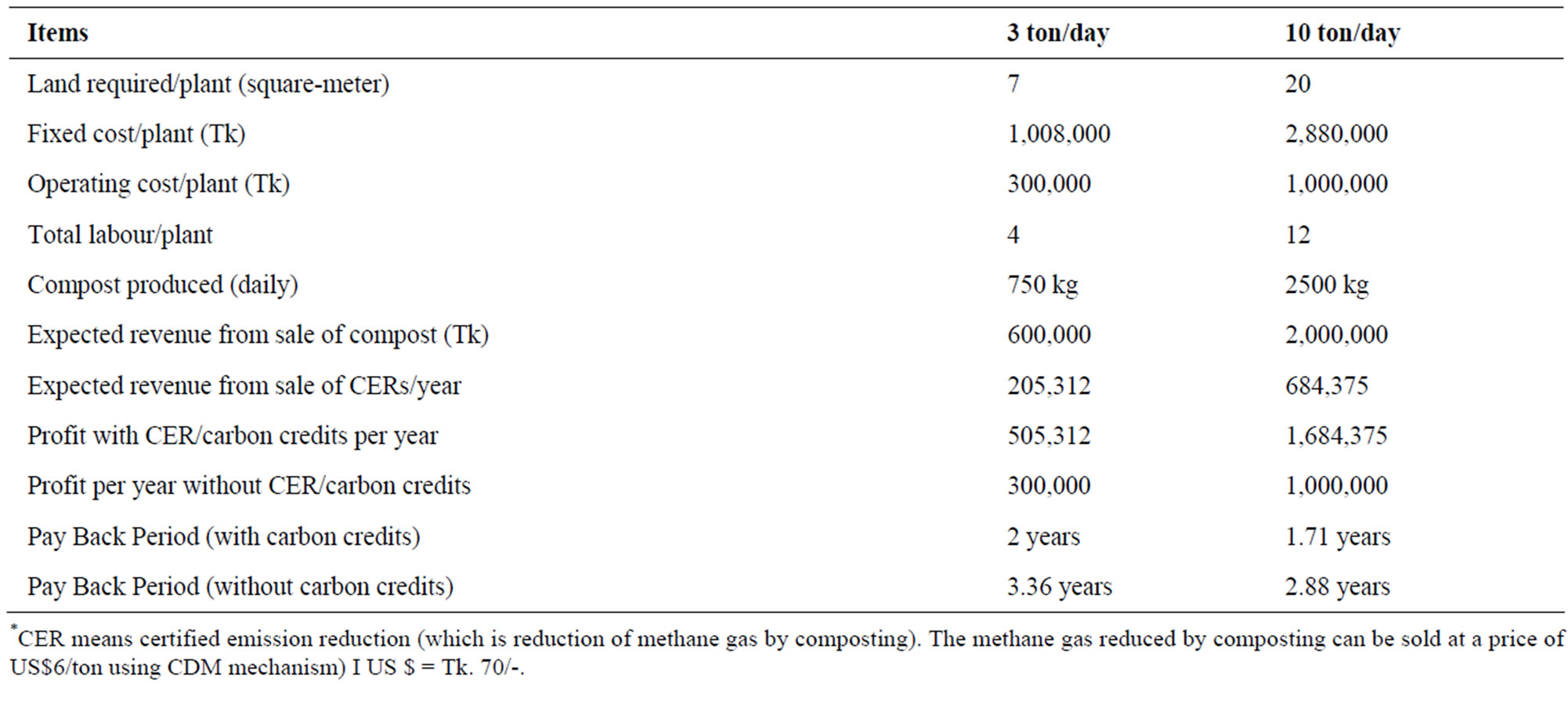

Initial investment was US $14,300 for a 3 tons/day capacity plant. Annual financial savings were US $7218 for a 3 tons/day capacity plant (both from plants and carbon credits). WC arranges for fertilizer companies to purchase and market the compost-based fertilizer. Table 1 shows the comparative cost analysis of different composting plants in Dhaka operated by Waste Concern.

In a joint venture project with a Dutch company, WC has built a 700 tons/day capacity compost plant under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) of the Kyoto Protocol. This joint venture company is under the for-profit organization so the profit will be distributed and the investment of the project will be pay back after certain time period. The newly build plant has the compost production capacity of 50,000 tons/year, reducing CO2 emissions by 560,000 tons over the next 6 years, benefiting more than 3.6 million people each year and directly creating jobs for 16,000 people from lower socio-economic backgrounds, especially women. The plan will reduce more than 18,000 tons of CO2 emissions each year in Bangladesh and will help to reduce the 52% of generated solid waste that remains uncollected in Dhaka.

5. Results and Discussions

Even though, social business is an emerging concept, it has already been accepted by the business expert very

Figure 3. Resource flow in Waste Concern’s business model.

Table 1. Financial costs for the current composting plants [47].

promptly especially in Asia and Europe due to its potential impacts on economy, society and the overall environment. Most of the social businesses currently run in the world are working in the poverty and health sectors, for example, Grameen Danone and Grameen Veolia. Waste is one of the biggest human generated problems in every country around the world. Social business models can assist local authority to ensure a better closed-loop material flow within society by providing a platform of reuse, recycling and resource recovery facility to the local community.

However, it is important to keep in mind that SB is an emerging business concept and waste management systems require long term investment. In addition, the traditional waste management business model is facing various problems in the competitive business market. Therefore, potential barriers in formulating innovative business models like SB are essential to consider and finding possible resolutions to overcome those barriers is a key driver in the success of SB in zero waste management systems.

5.1. Barriers and Opportunities in Waste Management Social Business

5.1.1. Potential Funding Partners or Investors

Potential funding partners or investors are the key factor in SB. Without appropriate funding partners SB cannot be established. In a profit maximizing company, the investor invests because of benefits. However, in social business, profit is non-dividend. Therefore, investor will not receive any profit margin from the company because of the SB principle which is to provide social, economic and environmental benefits to the society rather than personal benefit. There are many donors around the world who are interested in contributing significantly to change life and society through charity. Social enterprise is a business model which is based on charitable money and always depending on the charity organizations. In Australia, a total 7302 not-for-profit organizations received AU$10.5 billion in 2006-2007 and employed 110,482 people (ABS, 2009). However, there is a significantly low contribution by the donor in the waste management systems. Therefore, the potential funders or investors would come from different part of our society such as larger company, corporate company, government, regional or global development organization such as World Bank,, United Nations European Union and so on.

One of the potential strengths of the SB model is that SB can be a self-sufficient for-profit organization and can run independently without further assistance from the funding organization after running the business. Traditional corporate business funds and assists different programmes around the world through corporate social responsibility. Therefore, it would be an opportunity for the corporate world to utilize their money in more appropriate ways and contribute to social, economic and environmental benefits though social business models.

Waste Concern’s case is impressive in regards to the socio-economic context. Bangladesh is one of the least developed countries with diverse socio-economic, political and environmental problems. The Dhaka City Corporation (DCC) can’t provide sufficient waste management services to the inhabitant of Dhaka city. Inspiringly, using community-based waste collection systems and partnership with international funding body, Waste Concern collects household waste and separates and sorts-out organic fractions by hand. Funding bodies especially the charity organization are interested to be involved with WC and allocate funds for composting organic waste because, the system improves the environment in Dhaka but also creates jobs for a thousand people and creates profit making products such as bio-fertilizer from household garbage.

5.1.2. Social Acceptance

Social business is dependent on survival strength in the competitive business market and social acceptance. On one hand, the waste management social business model is primarily dependent on the collection of valuable resources from the waste streams, on the other hand, profitability of the business is also dependent on the social acceptability of purchasing the second-hand or repaired goods. Business credibility is also determined by the transformation of waste rubbish to a very attractive product.

In the recent past, community engagement has been amplified in different socio-economic and environmental movements due to the easy access of different social networks such as Facebook, Twitter and so on. Social acceptance has also been increased significantly for e-business like EBay or Amazon, where second hand functional products are reused again and again. Therefore, current society is progressing towards in shared values and collaborative consumption which leads to optimism in the waste management social business sector.

FWS sells their products to local consumers with a great deal of consumer satisfaction. Clients of FWS also feel good while buying products, not only because of the products are cheap but also because they are contributing to the society through reusing the products again and again. The case of Waste Concern is also positive when it comes to social acceptance. WC promotes their organic-fertilizer through a continuous testing of the nutriation value to the soil and the productivity of organic foods. The local farmer find organic-fertilizer is more productive with low price and environmental benefits.

5.1.3. Community Engagement

Capacity building within society is an important aspect for the success of the SB model. The SB model for zero waste management systems will engage and provide training on resource collection, repair, and reuse to the local people. SB can be a training place for different groups of people and it will provide information on the benefits of resource recovery, reuse or sharing and transform a hyper-consumption society to a collaborativeconsumption society.

Reuse the functional items such as re-usable electronic, furniture, equipment and so on can potentially prolong and indirectly prevent the waste generation. Thus the SB model can be useful to the local people to be engage with one another and make connection.

For instance, social business can be convenient place to resource drop off facility in a community. Therefore, SB would potentially provide a common meeting place where people can meet each other. Social business can be treated as a social place or “third place” where every single individual in a society can be part of the resource recovery and reuse programmes. Various awareness programme can be run under the SB model where different age groups can be involved specially elderly people who needs opportunity to involve in social activates. The case of FWS and WC are good example of involving local people and creating social bonding.

5.1.4. Waste Infrastructure

Existing waste infrastructure is a vital component for success of the SB model in any particular geographical area. The location of waste facility and accessibility are the key factors to encourage local people to recycle waste to the drop-off facility. In Adelaide, there are plenty of hard rubbish is produced every day and a significant portion of that waste is functional and reusable. People usually leave drop off hard rubbish at the curb-side due to remote drop-off facilities. People are not interested to take their hard rubbish to the remote drop off facilities due to cost for per unit deposit system. In the Figure 4 shows the response of the free drop-off day in Adelaide where most of the e-waste can be repaired recycled.

Given the example of the drop off facilities in Europe and many other countries around the world, where government organize the drop off facilities without any fees. A significant amount of funds needed to subsidies for such programme. SB can be a potential economic model for such kind of programme to run in profitable way.

Waste management social business can be used as a common drop-off centre of all recyclables for the local community. Therefore, waste management social business can play an important supporting role to the local government in context of providing waste management drop-off facility to the community. Repairable and reus-

Figure 4. E-waste in a free e-waste drop-off depot in Adelaide, Australia [48].

able waste will be repaired and then sold or exchanged to the local community. Local people can use social business as an exchange centre so that they can swap goods from the reusable product available in the shop. Therefore, social business can be more efficient and socially acceptable for promoting collaborative consumption to the society.

5.1.5. Competitive Waste Management Business Market

Waste business market structure is very competitive due to the profitability of waste to resource conversion. Waste businesses are also attractive to investors. Support from the local authority and policy makers is important for surviving in the business market. On one hand, social business model is a provider of social benefits to society. On the other hand, it is also a profit maximizing business organization. Therefore, to compete in the existing business model is comparatively challenging for social business. An innovative and profitable business plan can boost the business model and make it successful. The case of Finding Workable Solutions and Waste Concern are the examples of the waste management business with social benefits.

Both FWS and Waste Concern are profitable business enterprise. Therefore, social business would be more beneficial and socially acceptable to society and promoting recycling and resource recovery. Local policies such as container deposit legislation, landfill ban and extended producer responsibility could be supporting instruments for the waste management social business organizations.

5.1.6. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) and Social Business

EPR is an important strategy to promote products stewardship and products “take-back” by the producers in a responsible manner. However, the EPR strategies are not significantly implemented in every cities. Cities which are trying to be a “zero waste city” is still yet to reach a successful application of EPR for all product items such as electronic, paper and packaging and so on. One of the main barriers of implementing of EPR is the recycling or waste management infrastructure of the end-of-life products. Social business can take the responsibility of the successful implementation of the EPR with the corporate social responsibility.

Knowing the fact that, EPR is still need a long way to go to be successful and producer will produce as much product as they can but changing current production design to a more sustainable design such as “cradle-to cradle” design can improve the overall waste prevention at the first stage of waste creation. And at the end-of-life product, the SB can be used as important business partner to implement the take back or EPR policy successful. It is also important to acknowledge that as long as individual, community and society take the responsibility for the end-of-life products there will be very little achievement in waste in regards to economic growth and environmental benefits.

Therefore, social business will developed by the producers and consumers for the proper take-back systems under the umbrella of social business. Social business will work as a joint venture of the corporate business to solve the waste problems in the current society and integrate CSR as an effective tool in the contribution of the social benefits. Therefore, there is a huge opportunity to integrate the CSR within the product life cycle and empower the business responsibility with the help of social business models.

5.2. Waste Management Social Business Model

Waste management social business is an opportunity to contribute to socio-economic and environmental benefits in society and minimizing inequity. Waste management social business will not only provide job opportunities to local people but also it will be a platform to exchange ideas, promote environmental best management practices and share functional products. In the current business model, revenue is the prime concern and social or environmental benefits are the minor concern.

Waste management social business can work as a helping hand to the local council in collecting, recycling and providing resource recovery facilities. Waste management social business need to develop in such a way that people would feel free to visit the store frequently. Moreover, social businesses would offer different awareness raising programme to the local community.

In the current linear society products are used on a very temporary basis with a very short life span. Even though many products have a longer life span and are functional, after certain period they treated as waste and disposed off, most of the household wastes are recyclable, reusable, shareable or recoverable through composting, however, due to limited faculties and awareness those usable products are being disposed of in landfill.

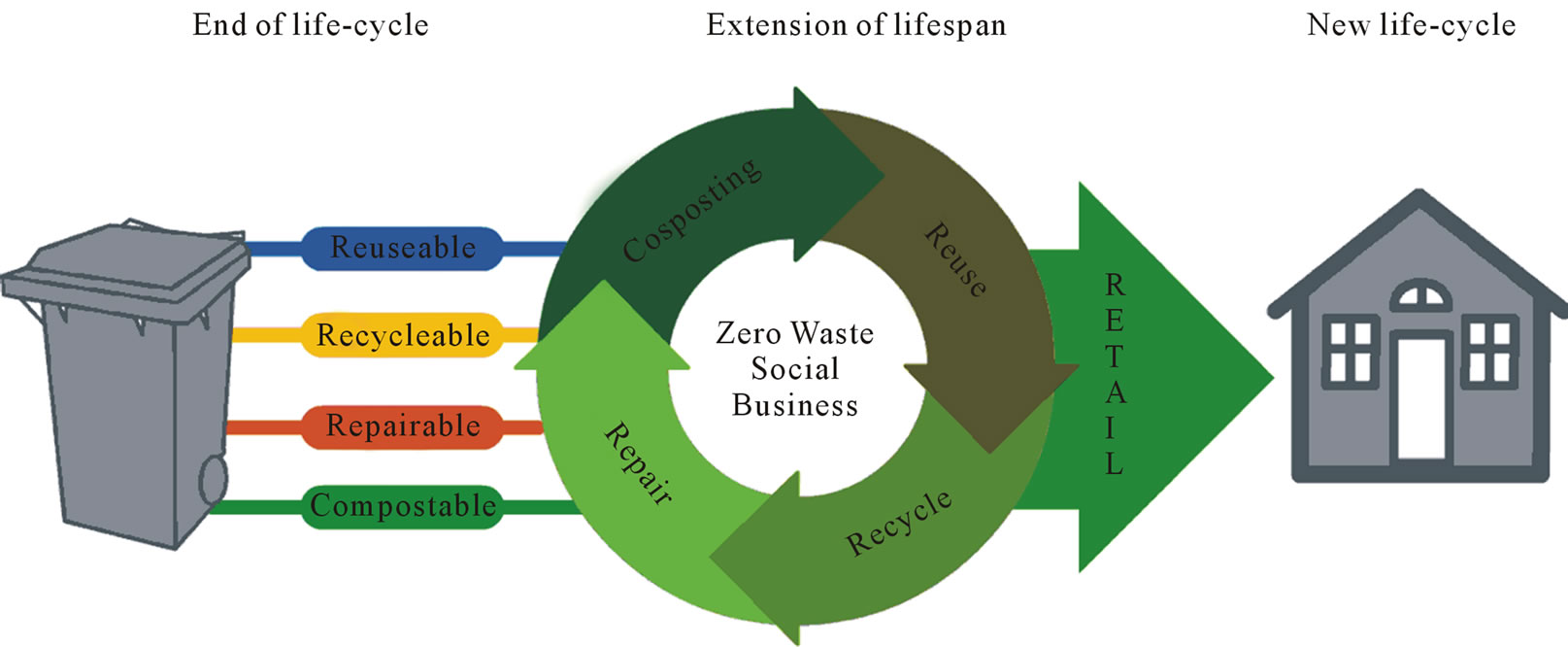

In this waste management social business model, the organization will act as a service provider to the community by recycling, reusing, repairing, composting and retailing goods to local people and circulating the material flow within society for a longer time period. Figure 5 shows the expansion of product lifecycle and transformation of linear society to a circular society through the waste management social business model.

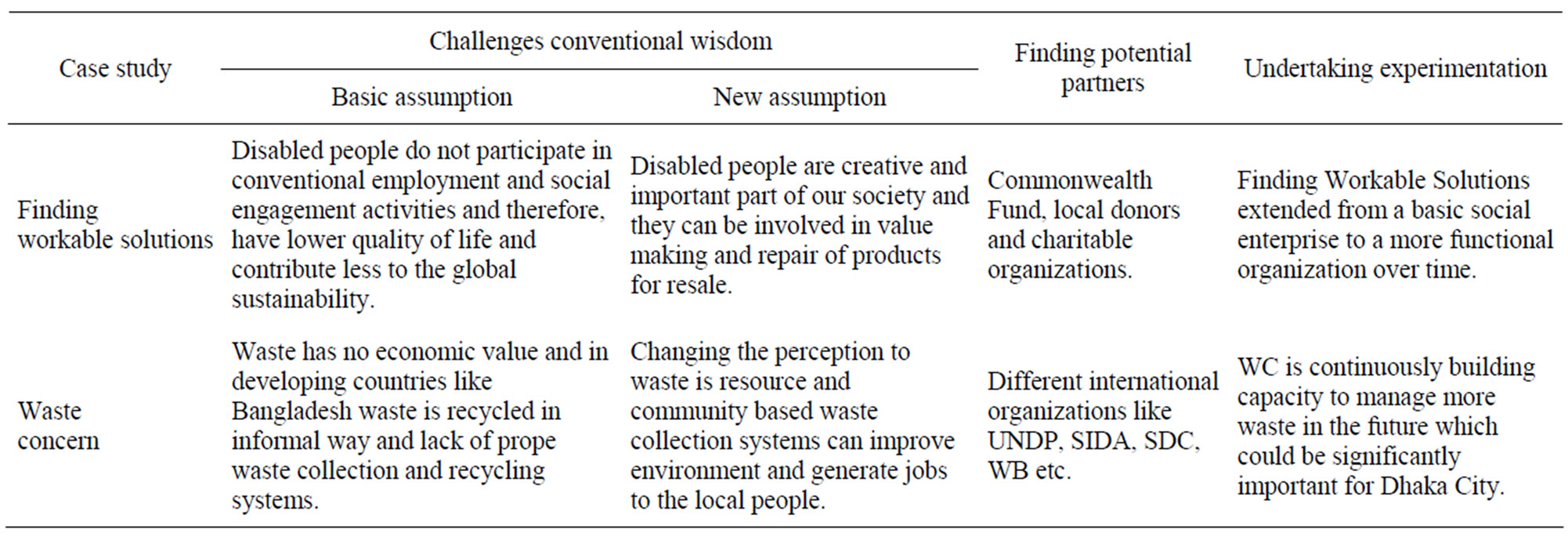

An experimentation and discovery driven approach based on new assumptions is required to overcome the existing barriers in current business practices and to develop an innovative new business model. Yunus’s SB is developed based on three key components such as challenging the conventional business model based on new assumptions, finding partners and undertaking experimentation. Table 2 shows the discovery driven waste management social business approach for the case of FWS and WC.

Figure 5. Product lifecycle expansion through waste management social business.

Table 2. Discovery driven waste management social business approach (adapted from Yunus et al. 2010).

6. Conclusions and Further Studies

The zero waste management social business model is an innovative business concept where existing corporate business partners can invest to develop a new business within the scope of corporate social responsibility. The current trends of contribution of CSR in solving social problems and promoting sustainable development are insignificant. The proposed waste management social business can improve the current waste management problems in our society, provide jobs to local people and can save our global finite resource.

The conceptualized social business model can endorse closed-loop resource flow in the circular society and it can maximize resource utilization through recycling and reusing so-called “solid waste” and prevent environmental depletion. The proposed business model will not only promote resource utilization through recycling and reuse but will also create a social meeting place or a “third place” which is an opportunity for promoting liveability in a city to its residents.

Key issues in the success of the zero waste social business are:

• Finding a potential funding partner is mandatory. Different corporate organizations can be potential investors. Financial mechanism can be incorporated into the traditional CSR system to utilize and finance the most innovative business model that can contribute to the transformation of society for the long term.

• Local authority and government should provide a common platform where donors or investors can easily fund their projects under the social business model. Local government should play an intermediate partner of the donor and business organization.

• Waste management sector is very finance incentives in regards to long term investment. In addition current traditional waste business is dependent on incentives for profit maximizations. Social business can be an interesting plat form for the local authority to assist and build social capital by resource recovery and empowering people in the waste management sector.

• Public private partnership and maximum stakeholders involvement is important for the success of the SB. SB is an opportunity for the corporate world to be more responsible in the context of product and resource stewardship.

• An appropriate and detailed for-profit SB plan with future vision can inspire corporate investors to explore SB for zero waste management systems that solve our everyday waste problems by creating a zero waste society.

Further studies can be done to explore the existing business scenario, to identify potential business partners and to develop a social business plan for executing a real time waste management social business model in the existing business market.

7. Acknowledgements

This article was supported by the Zero Waste SA Research Centre for Sustainable Design and Behaviour (sd + b) at the University of South Australia. The Zero Waste SA Research Centre is an interdisciplinary research centre with interest and expertise in a wide range of environmental and sustainability issues.

REFERENCES

- Zeit Studios, “ZEITGEIST: Moving Forward,” Official Release, 2011. http://www.youtube.com/user/TZMOfficialChannel

- D. Evans, “Consuming Conventions: Sustainable Consumption, Ecological Citizenship and the Worlds of Worth,” Journal of Rural Studies, Vol. 27, No. 2, 2011, pp. 109-115. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2011.02.002

- J. Rice, “Ecological Unequal Exchange: Consumption, Equity, and Unsustainable Structural Relationships within the Global Economy,” International Journal of Comparative Sociology, Vol. 48, No. 1, 2007, pp. 43-72. doi:10.1177/0020715207072159

- A. U. Zaman and S. Lehmann, “Challenges and Opportunities in Transforming a City into a ‘Zero Waste City’,” Challenges, Vol. 2, No. 4, 2011, pp. 73-93. doi:10.3390/challe2040073

- M. Lampe and G. M. Gazda, “Green Marketing in Europe and the United States: An Evolving Business and Society Interface,” International Business Review, Vol. 4, No. 3, 1995, pp. 295-312. doi:10.1016/0969-5931(95)00011-N

- S. O. Idowu and B. A. Towler, “A Comparative Study of the Contents of Corporate Social Responsibility Reports of UK Companies,” Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, Vol. 15, No. 4, 2004, pp. 420-437. doi:10.1108/14777830410540153

- J. Redmond, E. Walker and C. Wang, “Issues for Small Businesses with Waste Management,” Journal of Environmental Management, Vol. 88, No. 2, 2008, pp. 275- 285. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.02.006

- J. G. Longenecker, “Small Business Management: An Entrepreneurial Emphasis,” Thomson/South-Western, Mason, 2006.

- B. Christopher, “Confronting the Coffee Crisis: Can Fair Trade, Organic, and Specialty Coffees Reduce SmallScale Farmer Vulnerability in Northern Nicaragua?” World Development, Vol. 33, No. 3, 2005, pp. 497-511. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.10.002

- L. T. Raynolds, “Fair Trade,” International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, Elsevier, Oxford, pp. 8-13.

- T. Peter Leigh, “A Fair Trade Approach to Community Forest Certification? A Framework for Discussion,” Journal of Rural Studies, Vol. 21, No. 4, 2005, pp. 433- 447. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2005.08.002

- W. Nimon and J. Beghin, “Are Eco-Labels Valuable? Evidence from the Apparel Industry,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 81, No. 4, 1999, pp. 801- 811. doi:10.2307/1244325

- S. F. Hamilton and D. Zilberman, “Green Markets, Eco-Certification, and Equilibrium Fraud,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, Vol. 52, No. 3, 2006, pp. 627-644. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2006.05.002

- H. Nilsson, B. Tunçer and Å. Thidell, “The Use of Eco-Labeling Like Initiatives on Food Products to Promote Quality Assurance—Is There Enough Credibility?” Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 12, No. 5, 2004. pp. 517-526. doi:10.1016/S0959-6526(03)00114-8

- A. U. Zaman, M. Sofia and N. Veranika, “Green Marketing or Green Wash? A Comparative Study of Consumers’ Behavior on Selected Eco and Fair Trade Labeling in Sweden,” Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment, Vol. 2, No. 6, 2010, pp. 104-111.

- G. C. Nelson and R. D. Robertson, “Green Gold or Green Wash: Environmental Consequences of Biofuels in the Developing World,” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, Vol. 30, No. 3, 2008, pp. 517-529.

- V. Chettiyapan, “Business and Employment Opportunities in Waste Management and Recycling in Asia,” Waste Management, Vol. 31, No. 6, 2011, pp. 1083-1084.

- GIA, “Waste-to-energy market US$28.8 billion by 2015,” 2010. http://www.organics-recycling.org.uk/page.php?article=1165&name=Waste-to-energy+market+-+US%2428.8+billion+by+2015+

- M. Yunus and K. Weber, “Creating a World without Poverty: Social Business and the Future of Capitalism,” Public Affairs, New York, 2007.

- C. Henry, “Business Model Innovation: Opportunities and Barriers,” Long Range Planning, Vol. 43, No. 2-3, 2010, pp. 354-363. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.010

- M. Rita Gunther, “Business Models: A Discovery Driven Approach,” Long Range Planning, Vol. 43, No. 2-3, 2010, pp. 247-261. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.005

- NOS, “Objectives of Business,” 2011. http://www.nos.org/Secbuscour/cc03.pdf

- T. Volery and M. Schaper, “Entrepreneurship and small business,” John Wiley & Sons, Milton, 2007.

- W. D. Bygrave, “The Portable MBA in Entrepreneurship,” John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1997.

- C. Seelos and J. Mair, “Social Entrepreneurship: Creating New Business Models to Serve the Poor,” Business Horizons, Vol. 48, No. 3, 2005, pp. 241-246. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2004.11.006

- S. Rodney, “Building Social Business: The New Kind of Capitalism that Serves Humanity’s Most Pressing Needs,” Stanford University, Center for Social Innovation, Stanford, 2010, p. 18.

- M. Yunus, B. Moingeon and L. Lehmann-Ortega, “Building Social Business Models: Lessons from the Grameen Experience,” Long Range Planning, Vol. 43, No. 2-3, 2010, pp. 308-325. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2009.12.005

- C. L. Grameen, “The 7 Principles of Social Business,” 2011. http://www.grameencreativelab.com/a-concept-to-eradicate-poverty/7-principles.html

- W. McDonough and M. Braungart, “Design for the Tripple Top Line: New Tools for Sustainable Commerce,” 2002. http://www.mcdonough.com/writings/design_for_triple.htm

- WCED, “Our Common Future,” Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1987.

- K. Peattie and S. Peattie, “Social Marketing: A Pathway to Consumption Reduction?” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 62, No. 2, 2009, pp. 260-268. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.01.033

- R. A. Truscott, J. L. Bartlett and S. A. Tywoniak, “The Reputation of the Corporate Social Responsibility Industry in Australia,” Australasian Marketing Journal, Vol. 17, No. 2, 2009, pp. 84-91. doi:10.1016/j.ausmj.2009.05.001

- C.-H. Lin, H.-L. Yang and D.-Y. Liou, “The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Financial Performance: Evidence from Business in Taiwan,” Technology in Society, Vol. 31, No. 1, 2009, pp. 56-63. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2008.10.004

- W. Visser, “The Age of Responsibility: CSR 2.0 and the New DNA of Business,” Journal of Business Systems, Governance and Ethics, Vol. 5, No. 3, 2011, pp. 7-22.

- TVP, “Aims and Proposals of the Venus Project,” 2011. http://www.thevenusproject.com/en/the-venus-project/aims-a-proposals

- A. Fleming, “Adbusters Sparks Wall Street Protest: Vancouver-Based Activists behind Street Actions in the US,” 2011. http://www.vancourier.com/Adbusters+sparks+Wall+Street+protest/5466332/story.html

- R. Lowenstein, “Occupy Wall Street: It’s Not a Hippie Thing,” 2011. http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/occupy-wall-street-its-not-a-hippie-thing-10272011.html

- H. Chesbrough and R. S. Rosenbloom, “The Role of the Business Model in Capturing Value from Innovation: Evidence from Xerox Corporation’s Technology Spin-Off Companies,” Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 11, No. 3, 2002, pp. 529-555. doi:10.1093/icc/11.3.529

- S. L. Wartick and P. L. Cochran, “The Evolution of the Corporate Social Performance Model,” The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 10, No. 4, 1985, pp. 758-769. doi:10.2307/258044

- N. G. Mankiw, “Small Menu Costs and Large Business Cycles: A Macroeconomic Model of Monopoly,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 100, No. 2, 1985, pp. 529-537. doi:10.2307/1885395

- A. A. Costa and L. V. Tavares, “Social E-Business and the Satellite Network Model: Innovative Concepts to Improve Collaboration in Construction,” Automation in Construction, Vol. 22, 2012, pp. 387-397.

- A. D. Stajkovic and F. Luthans, “Business Ethics across Cultures: A Social Cognitive Model,” Journal of World Business, Vol. 32, No. 1, 1997, pp. 17-34. doi:10.1016/S1090-9516(97)90023-7

- G. Shrimali, et al., “Improved Stoves in India: A Study of Sustainable Business Models,” Energy Policy, Vol. 39, No. 12, 2011, pp. 7543-7556. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2011.07.031

- L. Darby and H. Jenkins, “Applying Sustainability Indicators to the Social Enterprise Business Model: The Development and Application of an Indicator Set for Newport Wastesavers, Wales,” International Journal of Social Economics, Vol. 33, No. 5-6, 2006, pp. 411-431. doi:10.1108/03068290610660689

- ASB, “Creative Partnerships: The Future for Corporate Social Responsibility?” 2010. http://knowledge.asb.unsw.edu.au/article.cfm?articleid=1208

- OEH, “Product Stewardship and Extended Producer Responsibility,” 2011. http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/warr/ProdStewardshipEPR.htm

- Waste Concern, “Waste Dhaka,” 2007. http://www.wasteconcern.org/latestNews/waste_dhaka.pdf

- ZWSA, “Free E-Waste Drop off Depot in Adelaide,” 2011. http://www.facebook.com/events/188879897868049/#!/photo.php?fbid=248408835223805&set=a.162491863815503.42194.118692401528783&type=1&theater