Creative Education

Vol.08 No.04(2017), Article ID:75699,16 pages

10.4236/ce.2017.84041

A Study on the Relationship between Well-Being and Turnover Intentions among Rural School Teachers: School Organizational Climate as a Moderating Variable

Cheng-Ping Chang1, Ling-Ying Chiu2, Jing Liu3*

1Department of Education, National University of Tainan, Taiwan

2Graduate Institute of School Entrepreneurship and Management, College of Education, Tainan University, Taiwan

3School of Business, Macau University of Science and Technology, Macau, China

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: March 8, 2017; Accepted: April 21, 2017; Published: April 27, 2017

ABSTRACT

This study examined the effect of teacher well-being and the organizational climate in rural elementary schools on teachers’ turnover intentions, as well as the effect of the interaction between teacher well-being and organizational climate on teachers’ turnover intentions. Teachers from rural elementary schools in Nantou County, Taiwan, were the participants in this study. A questionnaire was distributed and surveys were collected from 254 teachers. SPSS statistical software was used to conduct confirmatory factor analysis, reliability analysis, descriptive statistics analysis, independent-samples t-tests, one-way ANOVA, Pearson’s correlation analysis, and hierarchical regression analysis. The findings in this study were as follows: 1) Male and female teachers in rural elementary schools showed a significant difference in the professional sharing construct of school organizational climate. 2) Teachers of different age, marital status, part-time position, years of service, and native land showed significant differences in the well-being constructs of life satisfaction and negative emotions. 3) Teachers of different marital status showed a significant difference in the school organizational climate constructs of work supervision, teaching constraints, and turnover intentions. 4) Teachers from different places showed a significant difference in the estrangement construct. 5) The influence of teacher well-being on turnover intentions was negatively affected by the school organizational climate constructs of support, work supervision, and comradeship. The constructs of teaching constraints and estrangement had a significant and positive effect on turnover intentions. Thus, school organizational climate had a moderating effect on the relationship between teacher well-being and turnover intentions.

Keywords:

Teacher Well-Being, School Organizational Climate, Turnover Intentions, Rural Elementary School Teachers

1. Introduction

Workers are assets for a country’s prosperity. Education is the cradle in which workers are trained. In a talent-oriented country, training is a key to the country’s sustainable development and improved international competitiveness and is at the core of education work. Traffic and other inconveniences make it difficult to hire and retain teachers for teaching work in rural areas. It is common for rural schools to report that no teacher has yet been hired at the beginning of a new term. Even if a teacher is found in time, the school may be concerned that it will not be able to retain the teacher for the next year. Such high teacher turnover rates are caused by many factors, including a large amount of administrative work and a low sense of achievement. This has a major impact on the field of education. High turnover rates and high turnover intentions among teachers create a vicious cycle. A lack of suitable candidates leads to an employee shortage and increased work hours for teachers, which in turn affects students and does not benefit the accumulation of educational experience. Modern teachers are faced with changes in the educational environment, as well as internal and external stresses. This affects their self-efficacy and classroom management. Teachers are the main force behind and a key factor for a successful education. As many factors may affect teacher turnover, a comprehensive understanding of teachers’ moods, feelings, thinking, and well-being is of high importance. Hean and Garrett (2001) indicated that happier teachers perform better in their jobs. According to Taris and Schreurs (2009) , helping employees improve their well- being is not only important for the employees themselves, but also brings benefits to the organization and customers. A school is an official social organization that has a specific structure, standards, and value culture. A school organizational climate affects the school organization’s members as well as its students and their parents. Dellar and Giddings (1991) pointed out that the school climate is an important factor influencing school efficacy and an important predictor of effective teaching. To summarize, teacher well-being and the school organizational climate are closely related to a school’s future development, the quality of education, and teacher turnover and are, thus, worthy of deeper investigation.

This study conducted a survey among public elementary school teachers in rural areas of Nantou County, Taiwan, in order to examine the influence of teacher well-being and school organizational climate, as well as the interaction between them, on turnover intentions. The objectives of this study were as follows:

1) Investigate the current situation of teacher well-being and organizational climate at rural schools in Nantou County and empirically examine teachers’ turnover intentions under the current educational situation in rural Nantou County schools.

2) Evaluate the effect of teacher well-being and school organizational climate on teachers’ turnover intentions in rural Nantou County schools.

3) Evaluate whether school organizational climate has a moderating effect on the relationship between teacher well-being and turnover intentions in rural Nantou County schools.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Teacher Well-Being

Argyle (1987) claimed that well-being is a response to life satisfaction and a perception of the frequency and intensity of positive emotions. Chinese philosophy emphasizes the concept of harmony, while Western philosophy stresses the concept of happiness as the highest good. In both Chinese and Western cultures, well-being originates from pursuing after pleasing things in life and happiness is seen as a result of goodness. The perception of happiness is subjective and intrinsic and varies from person to person; each person pursues a different kind of happiness. There are several theories related to well-being, including the following: 1) Need satisfaction theory: Need satisfaction theory suggests that well-be- ing is generated through satisfaction of personal needs and a person can feel happiness only after satisfying his or her needs; in contrast, inability to satisfy needs for a long time leads to decreased well-being. 2) Trait theory: Trait theory states that the feeling of happiness is generated by individual traits and different individual traits can lead to feelings and experiences of different intensity. 3) Judgment theory: Diener (1984) suggests that well-being is a result of relativity and comparison. The feeling of happiness develops when an encountered situation is better than the predicted one. Well-being can be generated by comparing one’s life experiences with those of other people or against one’s own standards. 4) Dynamic equilibrium model: The theory of dynamic equilibrium suggests that the feeling of happiness is affected not only by long-term and stable personal traits but also by short-term life events.

Considering that this study aimed to examine the well-being of elementary school teachers who were invited as participants, a teacher well-being scale was developed referring to Yen and Hsu’s (2012) subjective well-being scale. The scale involved evaluation of life satisfaction on the cognitive level and positive and negative emotional experiences. A questionnaire was designed to examine well-being on three levels, namely, life satisfaction, positive emotions, and negative emotions.

2.2. School Organizational Climate

The concept of organizational climate in schools originates from public administration studies on organizational climate in general companies. School organizational climate is examined by means of theories, methods, and measuring tools used in research on company organizational climate. With regard to studies on organizational climate in schools, Halpin and Croft (1962) were the first to incorporate the concept of organizational climate into educational organizations. Organizational climate refers to the lasting internal environment of an organization created by the interactions between the organization’s members. The organizational climate is experienced by the organization’s members and affects their behavior. It can be described by the value of organizational characteristics. Research on organizational climate attaches importance to motivation, group dynamics, individual tendencies, and interpersonal relations (Sweetland & Hoy, 2000) .

Halpin and Croft (1962) maintained that school organizational climates are formed by interactions between school principals’ behaviors and teachers’ behaviors and built the Organizational Climate Description Questionnaire (OCDQ) based on the characteristics of school organizational climates. Hoy and Clover (1986) revised the OCDQ content, addressing its disadvantages, and developed the Revised Organizational Climate Description Questionnaire for Elementary Schools. Hoy, Tarter, and Kottkamp (1991) designed the Revised Organizational Climate Description Questionnaire for Secondary Schools. Hoy, Hoffman, Sabo, and Bliss (1996) developed the Organizational Climate Description Questionnaire for Middle Schools.

Considering that this study aimed to examine organizational climate in elementary schools and invited elementary school teachers as research participants, Huang’s (2013) school organizational climate questionnaire was used. The questionnaire items were designed based on the scale, which consists of six constructs: support, work supervision, teaching constraints, comradeship, professional sharing, and estrangement.

2.3. Turnover Intention

Turnover was first defined by Rice, Hill, and Trist (1950) as a type of a socialization process. Due to dissatisfaction with the interaction process after entering an organization, an employee may experience a crisis and leave the job. Turnover intention consists of an employee’s withdrawal behavior following his or her experience of dissatisfaction (Porter & Steers, 1973) . Mobley (1977) developed a model of the turnover decision process. According to Mobley, the degree of job satisfaction can influence whether an employee thinks of quitting. Dissatisfaction can cause negative behaviors, such as idleness and absence from work, resulting in thoughts of leaving. Price’s (1977) model of turnover, first published in 1977, emphasized causal relations between variables. According to the model, job satisfaction is affected by five factors, namely, rewards, recognition, feedback, communication, and centralization, while the interaction between job satisfaction and job opportunities can determine turnover behavior. Szilagyi (1979) proposed a turnover process model that integrated employment type, job satisfaction, personal traits, relations with colleagues, compensation system, organization business, job opportunities, and turnover intentions to explain turnover behavior. Abelson (1986) maintained that turnover is mainly affected by the interactions between individual, organizational, work, and environmental factors; a final turnover decision is normally made after long deliberation and a conscious decision precedes the notice of resignation. In their research on nursing staff, Lucas, Atwood, and Hagaman (1993) proposed a five-phase model, according to which turnover behavior is preceded by five phases of evaluation. The results of each phase in such a turnover process can be foreseen during the previous stage. Thus, an employee’s turnover intention can be predicted by determining personal variable factors and job expectations during the first phase.

Considering that this study aimed to examine turnover intentions among elementary school teachers who were invited as research participants, Mobley’s (1977) scale as revised by Cheng (2013) was employed in this study as a tool for collecting the data related to the teachers’ turnover intentions.

2.4. Relevant Research and Research Hypotheses Related to Each Variable

To provide a basis of support for the hypotheses, this study reviewed past research results related to teacher well-being, school organizational climate, and turnover intentions.

1) Research related to teachers’ well-being and turnover intentions

Teachers who are deemed “successful” are normally able to cope with working pressure, do not have symptoms of job burnout and are satisfied with their job (Kyriacou, 2001) . Determining the factors that can increase job satisfaction in teachers and improving their psychological feelings can greatly help to enhance teachers’ well-being. Well-being is an important indicator of psychological health and reflects the overall psychological health state. In Kyriacou and Sutcliffe’s (1978) study with teachers as participants, working pressure was seen as an important factor in teachers’ decision to quit their job. Mykletun and Mykletun’s (1999) study with 2800 Norwegian comprehensive school teachers as participants found that working pressure was one of reasons for turnover. Working pressure in teachers’ work is a negative subjective psychological state that affects happiness. Jackson, Rothmann, and Van de Vijver (2006) found a strong negative relationship between teachers’ working pressure and well-being. Studies on teachers’ professional well-being have tended to focus on such issues as working pressure, job burnout, and job satisfaction (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001) . Development and maintenance of subjective well-being in teachers can affect the classroom learning climate and the quality of education (De Jesus & Conboy, 2001; Patricia et al., 2001) and is positively related to teaching efficiency, having an impact even on students’ learning performance. Thus, well-being is related to job satisfaction and working pressure. Many studies have indicated a negative relationship between well-being and turnover intention, showing that turnover intention is decreased with a higher degree of well-being. Based on the above, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

H1: Teacher well-being has a significant and negative effect on teachers’ turnover intentions in rural elementary schools in Nantou County.

2) Research related to school organizational climate and turnover intentions

School organizational environment refers to a school staff’s perceptions of the working environment. Such perceptions can influence their behavior at work- place and job satisfaction (Lindell & Brandt, 2000) . Internal factors influencing school organizational climate include school principals’ leadership styles and educational ideas. Interactions on the individual, group, and organizational levels within a school determine social support in the workplace. Changes in organizational climate test teachers’ coping skills. School organizational climate and teacher well-being are inextricably related. A school constitutes the work- place of its teachers. Its organizational climate can influence their emotions, teaching styles and educational ideas, and methods of interacting with others. Many studies have found that the atmosphere among teachers who receive social support positively affects their job satisfaction, whereas the atmosphere among teachers with strained relations negatively affects their job satisfaction (Desh- pande, 1996; Zembylas & Papanastasiou, 2006) . Good interpersonal relations between school teachers largely improve the emotional background of their interactions with students and colleagues, as well as their teaching, and become a driving force of teachers’ progress. Based on the above, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

H2: School organizational climate has a significant effect on teachers’ turnover intentions in rural elementary schools in Nantou County.

3) Research on the moderating effect of school organizational climate on the relationship between teachers’ well-being and turnover intentions.

As stated by Lee and Ashforth (1996), job burnout is defined as a reaction to working pressure that can reduce job satisfaction and an employee’s partici- pation in work and strengthen his or her turnover intention. Pan and Qin (2007) indicated the presence of a significant positive relationship between organiza- tional climate and job satisfaction. The findings of Aarons and Sawitzky (2006), Hart (2005), Keuter et al. (2000), Parker et al. (2003), Rathert and May (2007), and Stone et al. (2007) showed that when corresponding to organization strate- gies, organizational climate influences organizational performance and deter- mines employees’ organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover. Some studies have also found that school principals’ caring behavior toward teachers and comradeship between teachers help to increase teachers’ job satisfaction (Aneshensel, 1992; Umberson, Chen, House, Hopkins, & Slaten, 1996) . In sum, organizational commitment, teachers’ social support, job satis- faction, and working pressure are closely related to school organizational climate. Studies related to turnover intentions have mainly focused on such variables as working pressure, job satisfaction, and organizational equipment, whereas very few studies have investigated turnover intentions from the perspective of school organizational climate. Furthermore, an online search for national theses and dissertations related to the relationships between teacher well-being, school organizational climate, and turnover intention indicated that this area is yet to be investigated. Therefore, this study aimed to empirically examine whether school organizational climate has a moderating effect on the relationship between teachers’ well-being and turnover intentions. Based on the above, this study proposed the following hypotheses:

H3: School organizational climate has a moderating effect on the relationship between teachers’ well-being and turnover intentions in rural elementary schools in Nantou County.

H4: The relationships between teacher well-being, school organizational climate, and turnover intention significantly differ depending on teachers’ general background variables.

3. Research Design and Implementation

3.1. Research Framework and Hypotheses

This chapter investigates the effect of teacher well-being and school organizational climate on teachers’ turnover intentions in rural elementary schools in Nantou County under a moderating effect of organizational climate. Drawing from the research background, literature review, and deductions in related studies, the following hypotheses were formulated within the research framework of this study:

1) H1: Teacher well-being has a significant and negative effect on teachers’ turnover intentions in rural elementary schools in Nantou County.

2) H2: School organizational climate has a significant and negative effect on teachers’ turnover intentions in rural elementary schools in Nantou County.

3) H3: Teachers’ turnover intentions are indirectly affected by school organizational climate through its effect on teacher well-being; school organizational climate in this case has a moderating effect.

4) H4: The relationships between teacher well-being, school organizational climate, and turnover intention significantly differ depending on teachers’ general background variables.

3.2. Source of Data

The data in this study was obtained from questionnaires completed by formal teachers in rural elementary schools of Nantou County that are listed in the Ministry of Education (MOE) rural junior high and elementary school information system and were identified by the Department of Education, Nantou County Government, as rural elementary schools of Nantou County in 2015. The total population included 366 teachers from 33 schools. To avoid the issue of repeated samples, 254 teachers from 21 schools received formal questionnaires after the deduction of 112 teachers from 12 schools who participated in the pilot study. All 253 questionnaires were returned by mid-April 2016. After eliminating one invalid response, 253 valid questionnaires were obtained.

3.3. Data Processing

To ensure correlation between the constructs of the three variables, including teacher well-being, school organizational climate, and turnover intentions, correlation analyses were first conducted. Hierarchical regression analysis was performed for school organizational climate and turnover intentions to verify that there was a moderating effect for the former.

3.4. Measures

Teacher well-being scale was developed referring to Yen and Hsu’s (2012) Subjective well-being scale. The scale involved evaluation of life satisfaction on the cognitive level and positive and negative emotional experiences. A questionnaire was designed to examine well-being on three levels, namely, life satisfaction, positive emotions, and negative emotions. School organizational climate questionnaire (Huang, 2013) was used. The questionnaire items were designed based on the scale, which consists of six constructs: support, work supervision, teaching constraints, comradeship, professional sharing, and estrangement.

4. Results and Discussion

The results of the descriptive statistics analysis, correlation analysis, and hierarchical regression analysis testing of the proposed hypotheses are presented below.

4.1. Correlation Analyses

With regard to the degree of correlation between different variables, a significant and moderate positive correlation was observed between teacher well-being and school organizational climate (r = .439; p < .01) and a weak negative correlation was observed between teachers’ well-being and turnover intentions (r = −1.24, p < .05), whereas no significant correlation was observed between school organizational climate and teachers’ turnover intentions. The results indicated that a higher degree of well-being among teachers resulted in more positive perceptions of the school organizational environment and lower turnover intentions, which corresponded to the hypotheses proposed in this study. Correlations between the constructs and turnover intentions are presented in Table 1. Except for negative emotions, all constructs were found to be significantly correlated with turnover intentions, findings which are discussed further below.

4.2. Regression Analysis Results

1) Relations between variables

After ensuring the absence of collinearity, this study used hierarchical regression analysis to examine the moderating effect of school organizational climate on the relationship between teachers’ well-being and turnover intentions. Hierarchical regression analysis was performed for four models. In Model 1, turnover intention was set as a dependent variable and teacher well-being as a predictor. In Model 2, school organization climate was integrated as a moderating variable in order to evaluate its moderating effect. The results of the regression analyses are presented in Table 2. Analysis of Model 1 and Model 2 showed that significant levels were achieved by teacher well-being (F = 33.501, p < .001) and school organizational climate (F = 29.194, p < .001). The total variation (R2) of teacher well-being was .114, with the β coefficient equal to −.343 (p < .001). The total variation of school organizational climate was .183, with the β coefficient equal to .268 (p < .001). This indicated that positive organizational climate in the school can reduce turnover intentions, thus having a positive moderating effect. In contrast, negative organizational climate in the school can strengthen turnover intentions, thus having a negative moderating effect.

2) Interference effects between variables

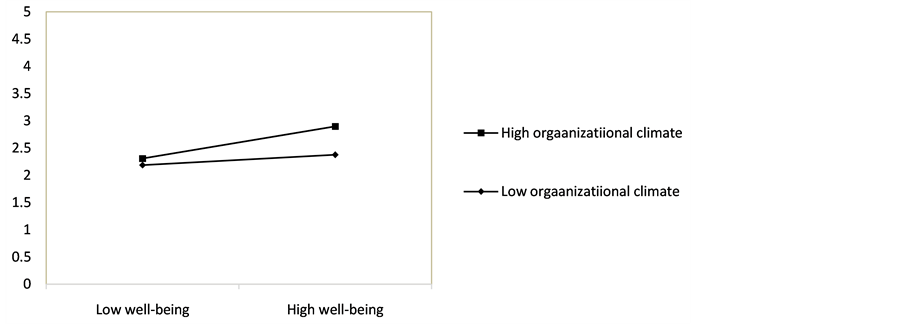

Independent and interference variables were standardized, producing two standardized coefficients. Multiplication of the two standardized coefficients by each other was converted into a new variable. Hierarchical regression analysis was conducted for three standardized coefficients in relation to turnover intentions to test the differences in regression coefficients. The results indicated that the standardized coefficient of well-being, as well as school organizational climate, was related to significant differences in turnover intentions. However, no

Table 1. Correlations in each scale.

Note: * indicates p < .05; ** indicates p < .01; *** indicates p < .001.

Table 2. Hierarchical regression analysis of the moderating effect of school organizational climate on the relationship between teachers’ well-being and turnover intentions.

Note: * indicates p < .05; ** indicates p < .01; *** indicates p < .001.

significant difference was observed in turnover intentions when the standardized coefficients were multiplied by each other, indicating their significant interference effect on turnover intentions (Table 3 and Figure 1).

4.3. General Discussion

Herein, the empirical results of this study are compared with those reported in theprevious literature and the reasons for their discussion are clarified.

1) H1: Teacher well-being has a significant and negative effect on teachers’ turnover intentions in rural elementary schools in Nantou County.

a) Research findings

H1 was supported in this study, i.e., teacher well-being had a significant and negative effect on teachers’ turnover intentions in rural elementary schools in Nantou County. An empirical investigation of teachers from rural elementary schools in Nantou County showed that teachers’ age, maritalstatus, part-time position, years of service, and native land significantly differed in such constru- cts as job satisfactionand negative emotions.

b) Comparison with past studies

With regard to past empirical studies, the findings in this study correspond to those reported by Porter and Steers (1973) , Skaalvik and Skaalvik (2011) , Yen and Hsu (2012) , Cheng (2013) , and Katz, Greenberg, Jennings, and Klein (2016) .

Table 3. Interference effects between regression coefficients of the variables.

a. Dependent variable: Turnover intentions.

Figure 1. Regression coefficient interfere.

According to Skaalvik and Skaalvik (2011) , job satisfaction can predict teachers’ turnover behavior and is correlated with emotional exhaustion. Katz et al. (2016) reported a negative effect of cumulative stress on teachers’ health and well-being. After reviewing over 60 studies on employee turnover, Porter and Steers (1973) found that job satisfaction is an important factor in the decision-making process of turnover.

Based on the results of this study and the verification of past research and theories, it can be concluded that the well-being of teachers in rural areas negatively affects their turnover intentions. Long-term maintenance of high levels of well-being in teachers experiencing a lack of resources in rural areas can thus reduce instances of turnover behavior.

2) H2: School organizational climate has a significant effect on teachers’ turnover intentions in rural elementary schools in Nantou County.

a) Research findings

With regard to H2, which suggests that school organizational climate has a significant effect on teachers’ turnover intentions in rural elementary schools in Nantou County, the empirical results in this study indicated a significant and negative effect of such school organizational climate constructs as support, work supervision, and comradeship on turnover intentions. In contrast, such constructs as teaching constraints and estrangement had a significant and positive effect on turnover intentions.

b) Comparison with past studies

With regard to past empirical studies, the findings in this study corresponded to those reported by Allen and Meyer (1993) . According to Allen and Meyer (1993) , the large amount of experience accumulated during a longer stay in an organization allows one to achieve a higher job position and gain more benefits, which increases job satisfaction and organizational commitment and ensures job security. In contrast, job dissatisfaction and low organizational commitment increase an employee’s turnover intention. Organizational commitment is an important factor that provides an insight into the behaviors of employees, helping to retain them and increasing the work performance of organization members.

Based on the results of this study and the verification of past research and theories, it can be concluded that school organizational climate in rural areas significantly influences teachers’ turnover intentions. Long-term maintenance of good organizational climates in elementary schools in rural areas where teachers experience a lack of resources can thus reduce turnover intentions and instances of turnover behavior. In contrast, turnover intentions and the occurrence of turnover behaviors are higher in schools with relatively negative organizational climates.

3) H3: School organizational climate has a moderating effect on the relationship between teachers’ well-being and turnover intentions in rural elementary schools in Nantou County.

a) Research findings

With regard to H3, which suggests that school organizational climate has a moderating effect on the relationship between teachers’ well-being and turnover intentions in rural elementary schools in Nantou County, the hierarchical regression analysis results indicated a significant effect of well-being on turnover intentions. A significant difference in turnover intentions was also caused by the school organizational climate, meaning that school organizational climate had a significant moderating effect on the relationship between teachers’ well-being and turnover intentions. Teachers who had positive feelings with respect to such school organizational climate constructs as support, work supervision, and comradeship demonstrated weaker turnover intentions, whereas negative feelings were associated with stronger turnover intentions. Moreover, negative feelings toward teacher constraints and estrangement also strengthened turnover intentions.

b) Comparison with past studies

Teachers work in the school environment and its organizational climate can affect teachers’ performance in the workplace (Dellar & Giddings, 1991) . According to Yousef (2000) , organizational commitment can better predict employees’ turnover intentions and work performance than job satisfaction and can serve as an indicator of organizational efficiency. Porter, Steers, Mowday, and Boulian (1974) considered organizational commitment as an attitude and intrinsic intention of organization employees that involved their recognition of the organization, diligence, and willingness to continue working in the organization. To summarize, the results of this study indicated that school organizational climate had a moderating effect on the relationship between teachers’ well-being and turnover intentions, having both positive and negative moderating roles. Thus, when faced with an adverse situation in terms of school organizational climate, school teachers in rural areas should develop coping skills in order to reduce negative emotions and balance the internal emotional resources. This can reduce the impact of school organizational climate on turnover intentions, allowing the objective of reduced turnover intentions to be achieved.

4) H4: The relationships between teacher well-being, school organizational climate, and turnover intention significantly differ depending on teachers’ general background variables.

a) Research findings

Background variables in this study included gender, age, marital status, position, years of service, and native land. According to the statistical analysis results, male and female teachers showed a significant difference in the professional sharing construct within school organizational climate. Teachers of different age, marital status, part-time position, years of service, and native land showed significant differences in such constructs of well-being as life satisfaction and negative emotions. Teachers of different marital status showed a significant difference in such constructs of school organizational climate as work supervision, teaching constraints, and turnover intentions. Teachers coming from different places showed a significant difference in the estrangement construct. Teachers’ education had no significant effect on teachers’ well-being, organizational climate, or turnover intentions. Based on the results of this study and the verification of past research and theories, it can be concluded that teachers who come to work in rural areas from other places have lower levels of well-being than local teachers. This means that when the work and living locations of teachers are not the same, distance, family, and adaptation factors may negatively influence stress and emotions, leading to increased turnover intentions.

5. Conclusion and Suggestions

Based on the results addressing the hypotheses of this study, the following conclusions and suggestions can be made. Teachers’ well-being has a significant direct effect on their turnover intentions. School organizational climate also has a significant direct effect on teachers’ turnover intentions. The relationship between teachers’ well-being and turnover intentions can have a moderating effect on such constructs of school organizational climate as support, work supervision, and comradeship. Gender causes a significant difference in the professional sharing construct within school organizational climate. Age, marital status, part- time position, years of service, and native land cause a significant difference in such constructs of well-being as life satisfaction and negative emotions. Marital status causes a significant difference in such constructs of school organizational climate as work supervision, teaching constraints, and estrangement. Native land causes a significant difference in the estrangement construct.

Based on the results, the following suggestions are made to serve as a reference for administrative authorities, school units, and school teachers working in rural areas. 1) It is recommended that education administrative authorities strengthen living support measures and provide legal protection to school teachers working in rural areas, establish a support system for school teachers in rural areas in order to improve their well-being, and improve the preparation of teachers and administrative staff in schools in rural areas in order to reduce their working pressure. 2) It is recommended that elementary schools located in rural areas develop a positive organizational climate, promote positive emotions in teachers, and jointly develop the school vision in order to prevent conflicts between the administration and teachers. 3) It is recommended that school teachers working in rural areas engage in self-learning and development and pass on their teaching experience, as well as organize proper leisure activities in order to increase their leisure satisfaction. 4) It is suggested that future studies extend the research scope of this study, integrate new research variables, and conduct qualitative and longitudinal research.

Cite this paper

Chang, C.-P., Chiu, L.-Y., & Liu, J. (2017). A Study on the Relationship between Well-Being and Turn- over Intentions among Rural School Tea- chers: School Organizational Climate as a Moderating Variable. Creative Education, 8, 523-538. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2017.84041

References

- 1. Abelson, M. A. (1986). Strategic Management of Turnover: A Model of the Health Service Administrator. Health Care Management Review, 11, 61-71.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00004010-198601120-00007 [Paper reference 1] - 2. Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1993). Organizational Commitment: Evidence of Career Stage Effects. Journal of Business Research, 29, 49-61. [Paper reference 2]

- 3. Aneshensel, C. S. (1992). Social Stress: Theory and Research. Annual Review of Sociology, 18, 15-38.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.18.080192.000311 [Paper reference 1] - 4. Argyle, M. (1987). The Psychology of Happiness. New York: Routedge. [Paper reference 1]

- 5. Cheng, W. C. (2013). A Study on the Correlations among Personality Traits, Organizational Commitment, and Turnover Intention of Junior High School Teachers in Kaohsiung City. Master Thesis, Pingtung, Taiwan: Department of Education, National University of Pingtung. [Paper reference 2]

- 6. De Jesus, S. N., & Conboy, J. (2001). A Stress Management Course to Prevent Teacher Distress. The International Journal of Educational Management, 15, 131-137.

https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540110384484 [Paper reference 1] - 7. Dellar, G. B., & Gidding, G. J. (1991). School Organizational Climate and School Improvement. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Education Research Association, Chicago, IL. [Paper reference 2]

- 8. Deshpande, S. (1996). The Impact of Ethical Climate Types on Facets of Job Satisfaction: An Empirical Investigation. Journal of Business Ethics, 15, 655-660.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00411800 [Paper reference 1] - 9. Diener, E. (1984). Subjective Well-Being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542-575.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542 [Paper reference 1] - 10. Halpin, A. W., & Croft, D. B. (1962). The Organizational Climate of School. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press. [Paper reference 2]

- 11. Hean, J., & Garrett, R. (2001). Sources of Job Satisfaction in Science Secondary School Teacher in Chile. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 31, 363-379.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920120098491 [Paper reference 1] - 12. Hoy, W. K., & Clover, S. I. R. (1986). Elementary School Climate: A Revision of the OCDQ. Educational Administration Quarterly, 22, 93-110.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X86022001007 [Paper reference 1] - 13. Hoy, W. K., Hoffman, J., Sabo, D. J., & Bliss, J. (1996). The Organizational Climate of Middle Schools: The Development and Test of the OCDU-RM. Journal of Educational Administration, 34, 41-59.

https://doi.org/10.1108/09578239610107156 [Paper reference 1] - 14. Hoy, W. K., Tarter, C. J., & Kottkamp, R. B. (1991). Open Schools/Healthy Schools: Measuring Organizational Climate. Newbury Park, CA: Corwin. [Paper reference 1]

- 15. Huang, S. H. (2013). The Relationships among Teacher’s Personality Traits, School Organization Climate, and the Professional Learning Community in Elementary Schools. Master Thesis, Department of Education, National University of Pingtung, Pingtung, Taiwan. [Paper reference 2]

- 16. Jackson, L. T. B., Rothmann, S., & van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2006). A Model of Work-Related Well-Being for Educators in South Africa. Stress and Health, 22, 263-274.

https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1098 [Paper reference 1] - 17. Katz, D. A., Greenberg, M. T., Jennings, P. A., & Klein, L. C. (2016). Associations between the Awakening Responses of Salivary α-Amylase and Cortisol with Self-Report Indicators of Health and Wellbeing among Educators. Teaching & Teacher Education, 54, 98-106. [Paper reference 2]

- 18. Kyriacou, C. (2001). Teacher Stress: Directions for Future Research. Educational Review, 53, 27-35.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00131910120033628 [Paper reference 1] - 19. Kyriacou, C., & Sutcliffe, J. (1978). Model of Teacher Stress. Educational Studies, 4, 1-6.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0305569780040101 [Paper reference 1] - 20. Lindell, M. K., & Brandt, C. J. (2000). Climate Quality and Climate Consensus as Mediators of the Relationship between Organizational Antecedents and Outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 331-348.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.331 [Paper reference 1] - 21. Lucas, M. D., Atwood, J. R., & Hagaman, R. (1993). Replication & Validation of Anticipated Turnover Model for Urban Registered Nurses. Nursing Research, 42, 29-35.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-199301000-00006 [Paper reference 1] - 22. Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leite, M. P. (2001). Job Burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397-422.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397 [Paper reference 1] - 23. Mobley, W. H. (1977). Intermediate Linkages in the Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Employee Turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62, 237-240.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.62.2.237 [Paper reference 2] - 24. Mykletun, R. J., & Mykletun, A. (1999). Comprehensive Schoolteachers at Risk of Early Exit from Work. Experimental Aging Research, 25, 359-365.

https://doi.org/10.1080/036107399243814 [Paper reference 1] - 25. Pan, X., & Qin, Q. (2007). An Analysis of the Relation between Secondary School. Education and Society, 40, 65-77. [Paper reference 1]

- 26. Patricia, F. B., Shirley, M. M., Gyda, B., Josette, J., Constance, V., & Michelle, R. (2001). HeartCare: An Internet-Based Information and Support System for Patient Home Recovery after Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) Surgery. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 35, 699-708.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01902.x [Paper reference 1] - 27. Porter, L. W., & Steers, R. M. (1973). Organizational, Work, and Personal Factors in Employee Turnover and Absenteeism. Psychological Bulletin, 80, 151-176.

https://doi.org/10.1037/h0034829 [Paper reference 3] - 28. Porter, L. W., Steers, R. M., Mowday, R. T., & Boulian, P. V. (1974). Organizational Commitment, Job Satisfaction and Turnover Among Psychiatric Technicians. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59, 603-609.

https://doi.org/10.1037/h0037335 [Paper reference 1] - 29. Price, J. L. (1977). The Study of Turnover. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press. [Paper reference 1]

- 30. Rice, A. K., Hill, J. M. M., & Trist, E. L. (1950). The Representation of Labor Turnover as a Social Process: Studies in the Social Development of an Industrial Community (The Glacier Project)—II. Human Relations, 3, 349-372.

https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675000300402 [Paper reference 1] - 31. Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2011). Teacher Job Satisfaction and Motivation to Leave the Teaching Profession: Relations with School Context, Feeling of Belonging, and Emotional Exhaustion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 1029-1038. [Paper reference 2]

- 32. Sweetland, S. R., & Hoy, W. K. (2000). School Characteristics and Educational Outcomes: Toward an Organizational Model of Student Achievement in Middle Schools. Educational Administration Quarterly, 36, 703-729.

https://doi.org/10.1177/00131610021969173 [Paper reference 1] - 33. Szilagyi, A. D. (1979). Keeping Employee Turnover under Control. The Management of People at Work, 56, 42-52. [Paper reference 1]

- 34. Taris, T. W., & Schreurs, P. J. G. (2009). Well-Being and Organizational Performance: An Organizational-Level Test of the Happy-Productive Worker Hypothesis. Work and Stress, 23, 120-136.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370903072555 [Paper reference 1] - 35. Umberson, D., Chen, M. D., House, J. S., Hopkins, K., & Slaten, E. (1996). The Effect of Social Relationships on Psychological Well-Being: Are Men and Women Really So Different? American Sociological Review, 61, 837-857.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2096456 [Paper reference 1] - 36. Yen, K. L., & Xu, M. W. (2012). A Study on the Relationship among Junior High School Teachers’ Orientations to Happiness, Teachers’ Subjective Well-Being and Teachers’ Organizational Commitment. Journal of Pingtung University of Education: Education, 38, 93-126. [Paper reference 3]

- 37. Yousef, D. (2000). Organizational Commitment as a Mediator of the Relationship between Islamic Work Ethic and Attitudes toward Organizational Change. Human Relation, 53, 513-537.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726700534003 [Paper reference 1] - 38. Zembylas, M., & Papanastasiou, E. (2006). Sources of Teacher Job Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction in Cyprus. Compare: A Journal of Comparative Education, 36, 229-247.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920600741289 [Paper reference 1]