Creative Education

Vol.05 No.20(2014), Article ID:51541,7 pages

10.4236/ce.2014.520201

Collaborative learning in maternity and child health clinics

Tiina Tervaskanto-Mäentausta1,2, Marja Ojaniemi3, Leila Mikkilä4, Leila Laitila-Özcok1, M. Niinimäki3, Tanja Nordström2, Anja Taanila2,5

1School of Health and Social Care, Oulu University of Applied Sciences, Oulu, Finland

2Institute of Health Sciences, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland

3University Hospital of Oulu, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland

4Health Care Centre, Oulu, Finland

5Primary Health Care Unit, Oulu University Hospital, Oulu, Finland

Email: tiina.tervaskanto-maentausta@oamk.fi

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 20 August 2014; revised 15 September 2014; accepted 8 October 2014

ABSTRACT

The health and wellbeing problems of the families with children have become more complex today. Improving preventive services and facilitating an early intervention in health and wellbeing problems of the families are the main challenges. A better interprofessional collaboration (IPC) of the professionals is needed to maintain the well-being level of the families high. These are skills to be learned during undergraduate education. An interprofessional pair training (IPT) for mater- nity and child health clinics was implemented in collaboration with primary health care centre and two universities of Oulu to develop an interprofessional education (IPE) model for undergraduate level students. Fifth year medical students (n = 101) and fourth year public health nurses (n = 31) and teachers participated in the training program during 2010-2012. The study aimed at investigating students’ attitudes and readiness for interprofessional learning (IPL), at strengthening their professional skills and at gathering clients’ experiences. The interprofessional student pairs met with the client visits independently. One pair contacted three clients during the day. They examined and observed the examination of the other pair. The feedback was collected from the students and the clients. Students’ attitudes and readiness for IPL were assessed using RIPLS (Readiness for interprofessional learning scale). Both medical and nurse students attached great importance to teamwork and collaboration. Nurse students appreciated the learning of roles and responsibilities more important in comparison to the medical students. A tendency for stronger professional identity among medical student was noted. The clients’ expectations were fulfilled. The training periods gave valuable experience to develop IP pair training for collaborative practices in primary health care and undergraduate health care education. The study results are important for curriculum development as well.

Keywords:

Collaborative pair training, maternity and child health care, interprofessional education, undergraduate medical studies, undergraduate nurse studies

1. Introduction

Finland has one of the lowest infant mortality rates in the world (Infant mortality rate; http://data.worldbank.org/), largely because of effective family support policy and preventive health care services (Arntzen et al., 2007; Hermanson et al., 1994) . Municipal healthcare centres run preventive maternity and child health clinics, which provide low-threshold services to all families and free of charge. Maternity and child health clinics are aimed to ensure a good standard for health for mothers, unborn children, infants and families as a whole. Personalized health advice is given to support the psychosocial and physical welfare of children and their parents. In addition, good parenthood, strong and healthy relations within the family and right choices for healthy lifestyle are supported. Health care professionals also actively seek best practices to enable families to take responsibility for their own health. Interprofessional (IP) team is providing the services. The main professionals in charge are public health nurses and medical doctors.

The services are used by almost 100% of families regardless of socio-economic status. However, the health and wellbeing problems of the families with children have become more complex today, (Häggman-Laitila, 2003; Häggman-Laitila & Euramaa, 2003) which has to be taken into account when providing and improving the preventive health services. Nowadays, socio-economic issues are more strongly connected to the health problems of the families and children (Gissler et al., 2009) . In spite of the good service system, new solutions and a better interprofessional collaboration (IPC) are now needed to maintain the wellbeing level of the families high. Improving preventive services and facilitating an early intervention in health and wellbeing problems of the families in a client-oriented and economically sustainable way are the main challenges according to Finnish Public Health program, Health 2015 (Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, 2013) .

Curriculum development in health care education aiming at health promotion and disease prevention skills is needed. Interprofessional education (IPE) models may serve as a good learning environment for such education. The study aimed at investigating students’ attitudes and readiness for interprofessional learning (IPL) and their learning experiences in preventive health care. The development of IPE and interprofessional training (IPT) at an undergraduate level challenges educational organizations (Hammick et al., 2007) and the health care educators (Zenzano et al., 2011) . In order to meet these challenges, an IPT model for preventive maternity and child health clinics was developed in collaboration with health care centre of the city of Oulu, University of Oulu (UO) and Oulu University of Applied Sciences (OUAS). Fifth year medical and fourth year public health nurse students participated in the training periods during the years 2010-2012. The second aim was to strengthen students’ professional skills by working with clients in a client centred manner. The third aim was to gather and evaluate clients’ experiences after the clinical visit.

2. Methodology

A planning group consisted members from each organisations. Detailed programs and timetables for the one day training periods were created. Orientation material was prepared for students. Two separate training days were arranged during each semester, one day in maternity- and the other in child health clinic. Altogether 132 (N = 31 public health nurse and N = 101 medical) students took part in training days.

Students were divided in IP pairs. Facilitators were named for each pair. The pairs planned the procedure of the visit, and examined the client. In addition, they observed and reflected the work of the others. A tool for observers was modified from Anaesthetists’ Non-technical Skills (ANTS, 2012) . It consisted several areas including task management, team working, situation awareness and patient centeredness and professional decision making. One pair operated the client’s visit independently, while another pair observed their working. Then the roles of the student pairs were switched so that finally all pairs completed all the tasks. All together six clients were examined during one day. Facilitators, doctors and nurses, were all the time available to guide and help. The feedback was collected from all the students (response rate 100%) and the clients (n = 94) by using questionnaires (Table 1 and Table 2).

The feedback questionnaire for the students (Table 1) consisted of background questions, structured statements according to RIPLS (Parsell & Bligh, 1999) and three statements of pair training(scale 1 totally agree −5 totally disagree) and two open questions.

Table 1. Student’s feedback questionnaire.

Table 2. Feedback questionnaire for clients.

Feedback questionnaire for clients (Table 2) consisted of three parts: background (age of the respondent, focus of health care visit), experiences of the visit (14 statements, scale 1 - 5) and evaluation of the treatment and service (five out of twenty adjectives to choose).

The quantitative data was analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 21 (1989, 2012 SPSS, Inc., an IBM company). The attitudes and readiness of medical and nurse students for IPL were investigated using the three subscales of RIPLS (Teamwork and collaboration, Professional identity, Roles and responsibilities) (Table 1) presented by Parsell & Bligh (1999) . The differences between medical and nurse students in these subscales were investigated by Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). The open questions were analyzed using the content analysis (Krippendorff, 2013) .

3. Results

3.1. Students’ readiness for the IPT

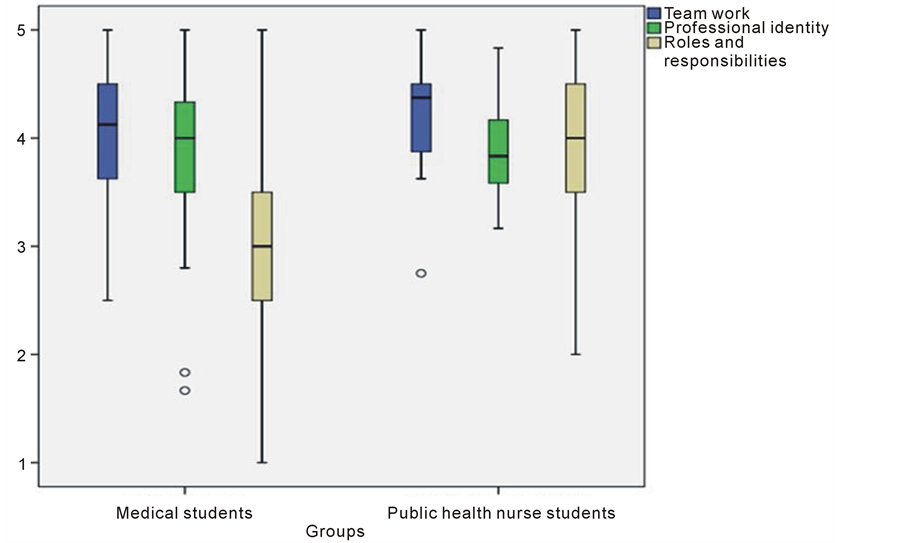

According to the results the students’ readiness and attitudes towards IPE were very positive in general (Figure 1). Working as an IP team was highly valuated in both of the student groups (medical students: M = 4.07, SD = 0.56; nurse students: M = 4.21, SD = 0.48; p = 0.194).

Statistically significant differences between medical and nurse students were seen in the subscales of roles and responsibilities (M = 3.18, SD = 0.81 vs. M = 4.06, SD = 0.80; p < 0.001). A tendency for a professional identity among medical students was lightly stronger compared to nurse students noted (M = 3.86, SD = 0.59 vs. M = 3.87, SD 0.42, p = 0.947), although the difference was not statistically significant.

Next, the readiness and attitudes of the students towards IPL were investigated in more detail. Considering the questions of teamwork and collaboration, over 90% of the students thought that learning with other students will help them to become more effective team members. Team-working skills were considered essential for all health care students to learn. In addition, about 90% of the students agreed thata patient ultimately benefits when the health care students worked together to solve a patient’s problems. Almost 100% of all students agreed that trust and respect for each team member is needed. Most of the students agreed that IPL before qualification will improve relationships after qualification, but there was some variance between the groups.

When evaluating the learning of the clinical or communication skills, more differences between the medical and nurse students were found (Figure 2(a) and Figure 2(b)). Nurse students seemed to learn more clinical skills (Figure 2(a)) whereas the medical students thought that this type of training could improve the communication skills (Figure 2(b)).

Both of the student groups highly disagreed the statement: “I don’t want to waste time in learning together”. Only 10% of the students thought that it is not necessary for undergraduate health care students to learn together. Two out of three students agreed that shared learning with other health care students will help them to communicate better with patients and other professionals and that teamwork clarifies the nature of patient problems. About 80% of medical and 90% of nurse students thought that shared learning before qualification will help them to become better team workers. Differences in opinions of the student groups about solving clinical problems were found (Figure 2(c)). Medical students were more prone to think that clinical problems can only be solved with students inside one’s own profession.

The questions about the roles and responsibilities showed that 17% of the medical students thought that the main role of the nurses and therapists is to provide support for doctors, whereas only few of the nursing students agreed with this statement. The difference between the groups was clear, but not significant (Figure 2(d)). 30% of medical and 20% of nurse students felt that they need to learn more than the others.

3.2. Pair Training experiences

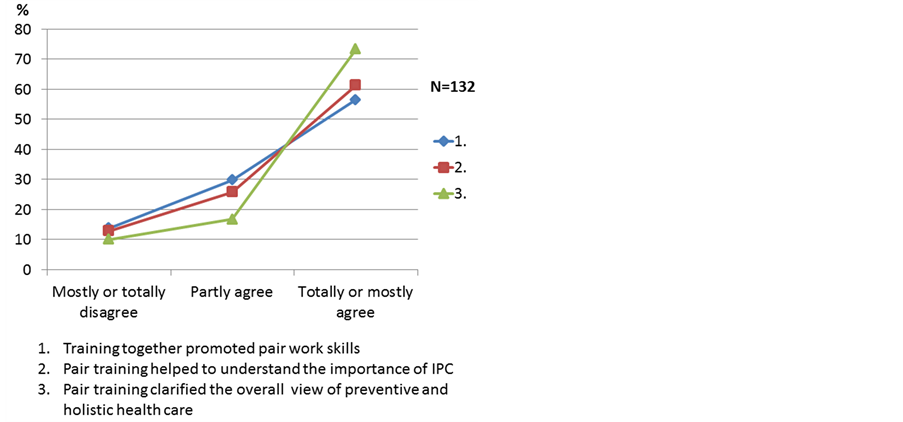

According to the assessment it seemed that the training promoted pair work skills of the students. IPL was considered important during the pair training. The students considered that they learned preventive and holistic patient and family centered care (Figure 3).

Positive experiences promoted learning but some of the students felt that they did not have enough earlier experience to fully benefit from this type of training and that they had not been prepared well enough. The professional roles of both professions were better understood and the students learned how to support each other. Overall, the students got familiar with preventive health care system during the training session.

Figure 1. The readiness and attitudes to IPL using RIPLS scales (1 totally disagree - 5 totally agree).

Figure 2. Differences in students’ perception of teamwork (a), collaboration (b), professional identity (c), roles and responsibilities (d).

Figure 3. Evaluation of pair training.

“I got good experiences of how the public health nurse and the doctor can support each other’s work”.

“Collaboration with the nurse student guided me to think from a different point of view”.

The focus of the training was based on holistic care of the patients and the whole families. IP pair work during the whole visit was a new model to train students in patient and family centered manner.

“It was challenging to work in a team and in the same time to keep the focus in the patient during the visit”.

“It was important to remember to support the parents and the family”.

3.3. Clients’ feedback

Altogether 94 of the clients answered to the feedback questionnaires (Table 2). Almost all of them agreed that the treatment was friendly, they were listened, the atmosphere was positive and the staff respected each other’s expertise. Most of them agreed that they got answers to their questions and that the guidance was understandable, staff performance was trustable and the examinations were done professionally and thoroughly. The staff worked in good cooperation. The feeling after the visit was good and they knew the care plan until the next visit.

4. Discussion

The focus of this research was to investigate IPT in the undergraduate medical and health care studies in order to develop curriculum focusing more to preventive skills. Teamwork has been emphasized as a key feature to organize health care services for more safe, efficient and patient centred way (Finn et al., 2010) . According to Bridges et al. (2011) training teamwork skills in primary care will focus to improved healthcare outcomes for patients and families. Team based approach to organize primary health care has been investigated and developed in many countries (Jaruseviciene et al., 2013; Goldman et al., 2010; Bunniss & Kelly, 2008) . However, these studies have been made with qualified doctors and nurses with the focus to improve messy roles and responsibilities of the health care teams.

Our study showed that the training periods gave a possibility for the students to work as equal health care professionals together in pairs. The students thought that they need to trust and respect each other and this showed good readiness for IPL and IPC. The active role of the patient and family as equal partners included in the training as well. Elements of collaborative practice include responsibility, accountability, coordination, com- munication, cooperation, assertiveness, autonomy, and mutual trust and respect (Bridges et al., 2011) . The students learn with, from and about each other (Barr et al., 2005) .

Both medical and nurse students considered teamwork and collaboration important (Figure 1). Morison et al. (2004) had similar findings in their study for undergraduate fourth year medical and third year nursing students. Also Williams et al. (2012) had similar findings of 418 students from seven health care programmes. According to both of these studies, the patients clearly benefited of IP teamwork.

According to our results, the students learned about their own professional identity during the training. Over 90% of the students thought that learning together with other health care students before qualification is very beneficial. The training to work as an IP pair succeeded well and students considered this type of training as a positive learning experience. In addition, they had much more skills and knowledge in use compared to the situation where they had to work alone. Working with the pair during the visit gave also confidence to meet the client. Our findings were more positive result than in the study by Morison et al. (2004) .

The results showed that training together increased understanding of the roles and skills of the other health care professionals. Differences between the medical and nurse students were seen in attitudes and readiness to solve clinical problems and to learn communication skills when working with other health care students (Figure 2(a), Figure 2(b)). Similar difference was seen in the previous study, although the difference between the medical and nurse students was clearer (Morison et al., 2004) .

The aim of IPT (Pare et al., 2012; Medves et al., 2013) was to learn patient centeredness in practice. Bridges et al. (2011) pointed that an IP team has to have common goals and they have to plan their work together to improve patient outcomes. Collaborative interactions are achieved through sharing skills and knowledge to improve the quality of patient care. In our study, according to the students’ opinion, more practice and common clients are needed to learn working with IP team and at the same time to keep the client’ needs and service in focus. According to the feedback of clients their expectations were fulfilled. To provide comprehensive client care, the clients thought that the students and staff worked in good collaboration as a team. The feeling after the visit was confident. They were listened and cared, thoroughly and carefully.

5. Conclusion

These training periods gave valuable experience to develop IP pair training for the future and for all of the health care students. The strategic plan to organise future health care services in Finland includes prevention and primary care. Sharing the tasks with doctors and nurses is one of the strategies.

The study results are important for curriculum development of medical and nursing studies. A new type of IP learning centre is developed together with city of Oulu and the two universities. It will be one part of the whole to produce the primary and preventive health care services in Oulu. The study gave important experience on how to carry out the facilitation of the students in IP collaboration with the teachers and the staff.

References

- (2012) . Anaesthetists’ Non-Technical Skills (ANTS): System Handbook v1.0. Aberdeen: University of Aberdeen. http://www.abdn.ac.uk/iprc/uploads/files/ANTS%20Handbook%202012.pdf

- Arntzen, A., Mortensen, L., Schnor, O., Cnattingius, S., Gissler, M., & Nybo Andersen, A.-M. (2007). Neonatal and Postneonatal Mortality by Maternal Education—A Population-Based Study of Trends in the Nordic Countries, 1981-2000. European Journal of Public Health, 18, 245-251. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckm125

- Barr, H., Koppel, I., Reeves, S., Hammick, M., & Fleeth, D. (2005). Effective Interprofessional Education: Argument, Assumptions and Evidence. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9780470776445

- Bridges, D. R., Davidson, R., Odegard, P. S., Maki, I. V., & Tomkowiak, J. (2011). Interprofessional Collaboration: Three Best Practice Models of Interprofessional Education. Medical Education Online, 16. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3081249/ http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035

- Bunniss, S., & Kelly, D. R. (2008). “The Unknown Becomes the Known”: Collective Learning and Change in Primary Care Teams. Medical Education, 42, 1185-1194. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03159.x

- Finn, R., Learmonth, M., & Reedy, P. (2010). Some Unintended Effects of Teamwork in Healthcare. Social Science & Medicin, 70, 1148-1154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.025

- Gissler, M., Rahkonen, O., Arntzen, A., Cnattingius, S., Nybo Andersen, A-M., & Hemminki, E. (2009). Trends in Socioeconomic Differences in Finnish Perinatal Health 1991-2006. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 63, 420- 425. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech.2008.079921

- Goldman, J., Meuser, J., Rogers, J., Lawie, L., & Reeves, S. (2010). Interprofessional Collaboration in Family Health Teams. Canadian Family Physician, 56, 368-374.

- Häggman-Laitila, A. (2003). Early Support Needs of Finnish Families with Small Children. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 41, 595-606. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02571.x

- Häggman-Laitila, A. , & Euramaa, K. (2003). Finnish Families’ Need for Special Support as Evaluated by Public Health Nurses Working in Maternity and Child Welfare Clinics. Public Health Nursing, 20, 328-338. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1446.2003.20410.x

- Hammick, M., Freeth, D., Koppel, I., Reeves, S., & Barr, H. (2007). A Best Evidence Systematic Review of Interprofessional Education: BEME Guide No. 9. Medical Teacher, 29, 735-751. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590701682576

- Hermanson, T., Aro, S., & Benneth, C. (1994). Finland’s Health Care System: Universal Access to Health Care in a Capitalistic Democracy. Journal of the American Medical Association, 271, 1957-1962.

- Jaruseviciene, L., Lisekiene, I., Valius, L., Kontrimiene, A., Jarusevicius, G., & Lapão, L. V. (2013). Teamwork in Primary Care: Perspectives of General Practitioners and Community Nurses in Lithuania. BMC Family Practice, 14, 118. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2296/14/118 http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-118

- Krippendorff, K. (2013). Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Thousand Oaks: Sage, Cop.

- Medves, J., Paterson, M., Broers, T., & Hopman, W. (2013). The QUIPPED Project: Students Attitudes toward Integrating Interprofessional Education into the Curriculum. Journal of Research in Interprofessional Practice and Education, 3. http://www.jripe.org/index.php/journal/article/view/34

- Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finland (2013). Health Care in Finland. http://www.urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-00-3395-8

- Morison, S., Boohan, M., Moutray, M., & Jenkins, J. (2004). Developing Pre-Qualification Interprofessional Education for Nursing and Medical Students: Sampling Student Attitudes to Guide Development. Nurse Education in Practice, 4, 20-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1471-5953(03)00015-5

- Pare, L., Maziane, J., Pelletier, F., Houle, N., & Ikolo-Fundi, M. (2012). Training in Interprofessional Collaboration. Pedagogic Innovation in Family Medicine Units. Canadian Family Physician, 58, 203-209.

- Parsell, G., & Blight, J. (1999). The Development of a Guestionnaire to Assess the Readiness of Health Care Students for Interprofessional Learning (RIPLS). Medical Education, 33, 95-100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00298.x

- Williams, B., WcCook, F., Brown, T., Palmero, C., McKenna, L., Boyle, M., Scholes, R., French, J., & McCall, L. (2012). Are Undergraduate Health Care Students “Ready” for Interprofessional Learning? A Cross-Sectional Attitudinal Study. The Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice, 10. http://ijahsp.nova.edu/articles/Vol10Num3/williams.htm

- Zenzano, T., Allan, J. D., Bigley, M. B., Bushardt, R. L., Garr, D. R., Johnson, K., Lang, W., Maeshiro, R., Mayer, S. M., Shannon, S. C., Spolsky, V. W., & Stanley, J. M. (2011). The Roles of Healthcare Professionals in Implementing Clinical Prevention and Population Health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 40, 261-267. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.023