Advances in Pure Mathematics

Vol.06 No.13(2016), Article ID:72855,50 pages

10.4236/apm.2016.613074

Approach to a Proof of the Riemann Hypothesis by the Second Mean-Value Theorem of Calculus

Alfred Wünsche

Humboldt-Universität Berlin, Institut für Physik, Nichtklassische Strahlung (MPG), Berlin, Germany

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: July 9, 2016; Accepted: December 17, 2016; Published: December 20, 2016

ABSTRACT

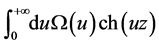

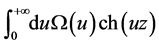

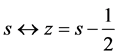

By the second mean-value theorem of calculus (Gauss-Bonnet theorem) we prove that the class of functions  with an integral representation of the form

with an integral representation of the form  with a real-valued function

with a real-valued function  which is non-increasing and decreases in infinity more rapidly than any exponential functions

which is non-increasing and decreases in infinity more rapidly than any exponential functions

possesses zeros only on the imaginary axis. The Riemann zeta function

possesses zeros only on the imaginary axis. The Riemann zeta function  as it is known can be related to an entire function

as it is known can be related to an entire function  with the same non-trivial zeros as

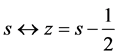

with the same non-trivial zeros as . Then after a trivial argument displacement

. Then after a trivial argument displacement  we relate it to a function

we relate it to a function  with a representation of the form

with a representation of the form  where

where  is rapidly decreasing in infinity and satisfies all requirements necessary for the given proof of the position of its zeros on the imaginary axis

is rapidly decreasing in infinity and satisfies all requirements necessary for the given proof of the position of its zeros on the imaginary axis  by the second mean-value theorem. Besides this theorem we apply the Cauchy- Riemann differential equation in an integrated operator form derived in the Appendix B. All this means that we prove a theorem for zeros of

by the second mean-value theorem. Besides this theorem we apply the Cauchy- Riemann differential equation in an integrated operator form derived in the Appendix B. All this means that we prove a theorem for zeros of  on the imaginary axis

on the imaginary axis  for a whole class of function

for a whole class of function  which includes in this way the proof of the Riemann hypothesis. This whole class includes, in particular, also the modified Bessel functions

which includes in this way the proof of the Riemann hypothesis. This whole class includes, in particular, also the modified Bessel functions  for which it is known that their zeros lie on the imaginary axis and which affirms our conclusions that we intend to publish at another place. In the same way a class of almost-periodic functions to piece-wise constant non-increasing functions

for which it is known that their zeros lie on the imaginary axis and which affirms our conclusions that we intend to publish at another place. In the same way a class of almost-periodic functions to piece-wise constant non-increasing functions  belong also to this case. At the end we give shortly an equivalent way of a more formal description of the obtained results using the Mellin transform of functions with its variable substituted by an operator.

belong also to this case. At the end we give shortly an equivalent way of a more formal description of the obtained results using the Mellin transform of functions with its variable substituted by an operator.

Keywords:

Riemann Hypothesis, Riemann Zeta Function, Xi Function, Gauss-Bonnet

Theorem, Mellin Transformation

1. Introduction

The Riemann zeta function ![]() which basically was known already to Euler establishes the most important link between number theory and analysis. The proof of the Riemann hypothesis is a longstanding problem since it was formulated by Riemann [1] in 1859. The Riemann hypothesis is the conjecture that all nontrivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function

which basically was known already to Euler establishes the most important link between number theory and analysis. The proof of the Riemann hypothesis is a longstanding problem since it was formulated by Riemann [1] in 1859. The Riemann hypothesis is the conjecture that all nontrivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function ![]() for complex

for complex ![]() are positioned on the line

are positioned on the line

![]() that means on the line parallel to the imaginary axis through real value

that means on the line parallel to the imaginary axis through real value

![]() in the complex plane and in extension that all zeros are simple zeros [2] - [17]

in the complex plane and in extension that all zeros are simple zeros [2] - [17]

(with extensive lists of references in some of the cited sources, e.g., ( [4] [5] [9] [12] [14] ). The book of Edwards [5] is one of the best older sources concerning most problems connected with the Riemann zeta function. There are also mathematical tables and chapters in works about Special functions which contain information about the Riemann zeta function and about number analysis, e.g., Whittaker and Watson [2] (chap. 13), Bateman and Erdélyi [18] (chap. 1) about zeta functions and [19] (chap. 17) about number analysis, and Apostol [20] [21] (chaps. 25 and 27). The book of Borwein, Choi, Rooney and Weirathmueller [12] gives on the first 90 pages a short account about achievements concerning the Riemann hypothesis and its consequences for number theory and on the following about 400 pages it reprints important original papers and expert witnesses in the field. Riemann has put aside the search for a proof of his hypothesis “after some fleeting vain attempts” and emphasizes that “it is not necessary for the immediate objections of his investigations” [1] (see [5] ). The Riemann hypothesis was taken by Hilbert as the 8-th problem in his representation of 23 fundamental unsolved problems in pure mathematics and axiomatic physics in a lecture hold on 8 August in 1900 at the Second Congress of Mathematicians in Paris [22] [23] . The vast experience with the Riemann zeta function in the past and the progress in numerical calculations of the zeros (see, e.g., [5] [10] [11] [16] [17] [24] [25] ) which all confirmed the Riemann hypothesis suggest that it should be true corresponding to the opinion of most of the specialists in this field but not of all specialists (arguments for doubt are discussed in [26] ).

The Riemann hypothesis is very important for prime number theory and a number of consequences is derived under the unproven assumption that it is true. As already said a main role plays a function ![]() which was known already to Euler for real variables

which was known already to Euler for real variables ![]() in its product representation (Euler product) and in its series re- presentation (now a Dirichlet series) and was continued to the whole complex

in its product representation (Euler product) and in its series re- presentation (now a Dirichlet series) and was continued to the whole complex ![]() -plane by Riemann and is now called Riemann zeta function. The Riemann hypothesis as said is the conjecture that all nontrivial zeros of the zeta function

-plane by Riemann and is now called Riemann zeta function. The Riemann hypothesis as said is the conjecture that all nontrivial zeros of the zeta function ![]() lie on the axis

lie on the axis

parallel to the imaginary axis and intersecting the real axis at![]() . For the true

. For the true

hypothesis the representation of the Riemann zeta function after exclusion of its only singularity at ![]() and of the trivial zeros at

and of the trivial zeros at ![]() on the negative real axis is possible by a Weierstrass product with factors which only vanish on the

on the negative real axis is possible by a Weierstrass product with factors which only vanish on the

critical line![]() . The function which is best suited for this purpose is the so-called xi

. The function which is best suited for this purpose is the so-called xi

function ![]() which is closely related to the zeta function

which is closely related to the zeta function ![]() and which was also introduced by Riemann [1] . It contains all information about the nontrivial zeros and only the exact positions of the zeros on this line are not yet given then by a closed formula which, likely, is hardly to find explicitly but an approximation for its density was conjectured already by Riemann [1] and proved by von Mangoldt [27] . The “(pseudo)-random” character of this distribution of zeros on the critical line remembers somehow the “(pseudo)-random” character of the distribution of primes where one of the differences is that the distribution of primes within the natural numbers becomes less dense with increasing integers whereas the distributions of zeros of the zeta function on the critical line becomes more dense with higher absolute values with slow increase and approaches to a logarithmic function in infinity.

and which was also introduced by Riemann [1] . It contains all information about the nontrivial zeros and only the exact positions of the zeros on this line are not yet given then by a closed formula which, likely, is hardly to find explicitly but an approximation for its density was conjectured already by Riemann [1] and proved by von Mangoldt [27] . The “(pseudo)-random” character of this distribution of zeros on the critical line remembers somehow the “(pseudo)-random” character of the distribution of primes where one of the differences is that the distribution of primes within the natural numbers becomes less dense with increasing integers whereas the distributions of zeros of the zeta function on the critical line becomes more dense with higher absolute values with slow increase and approaches to a logarithmic function in infinity.

There are new ideas for analogies to and application of the Riemann zeta function in other regions of mathematics and physics. One direction is the theory of random matrices [16] [24] which shows analogies in their eigenvalues to the distribution of the nontrivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function. Another interesting idea founded by Voronin [28] (see also [16] [29] ) is the universality of this function in the sense that each holomorphic function without zeros and poles in a certain circle with radius less

![]() can be approximated with arbitrary required accurateness in a small domain of the zeta function to the right of the critical line within

can be approximated with arbitrary required accurateness in a small domain of the zeta function to the right of the critical line within![]() . An interesting idea is

. An interesting idea is

elaborated in articles of Neuberger, Feiler, Maier and Schleich [30] [31] . They consider a simple first-order ordinary differential equation with a real variable ![]() (say the time) for given arbitrary analytic functions

(say the time) for given arbitrary analytic functions ![]() where the time evolution of the function for every point

where the time evolution of the function for every point ![]() finally transforms the function in one of the zeros

finally transforms the function in one of the zeros ![]() of this function in the complex

of this function in the complex ![]() -plane and illustrate this process graphically by flow curves which they call Newton flow and which show in addition to the zeros the separatrices of the regions of attraction to the zeros. Among many other functions they apply this to the Riemann zeta function

-plane and illustrate this process graphically by flow curves which they call Newton flow and which show in addition to the zeros the separatrices of the regions of attraction to the zeros. Among many other functions they apply this to the Riemann zeta function ![]() in different domains of the complex plane. Whether, however, this may lead also to a proof of the Riemann hypothesis is more than questionable.

in different domains of the complex plane. Whether, however, this may lead also to a proof of the Riemann hypothesis is more than questionable.

Number analysis defines some functions of a continuous variable, for example, the number of primes ![]() less a given real number

less a given real number ![]() which last is connected with the discrete prime number distribution (e.g., [3] [4] [5] [7] [9] [11] ) and establishes the connection to the Riemann zeta function

which last is connected with the discrete prime number distribution (e.g., [3] [4] [5] [7] [9] [11] ) and establishes the connection to the Riemann zeta function![]() . Apart from the product repre- sentation of the Riemann zeta function the representation by a type of series which is now called Dirichlet series was already known to Euler. With these Dirichlet series in number theory are connected some discrete functions over the positive integers

. Apart from the product repre- sentation of the Riemann zeta function the representation by a type of series which is now called Dirichlet series was already known to Euler. With these Dirichlet series in number theory are connected some discrete functions over the positive integers ![]() which play a role as coefficients in these series and are called arithmetic functions (see, e.g., Chandrasekharan [4] and Apostol [13] ). Such functions are the Möbius function

which play a role as coefficients in these series and are called arithmetic functions (see, e.g., Chandrasekharan [4] and Apostol [13] ). Such functions are the Möbius function ![]() and the Mangoldt function

and the Mangoldt function ![]() as the best known ones. A short representation of the connection of the Riemann zeta function to number analysis and of some of the functions defined there became now standard in many monographs about complex analysis (e.g., [15] ).

as the best known ones. A short representation of the connection of the Riemann zeta function to number analysis and of some of the functions defined there became now standard in many monographs about complex analysis (e.g., [15] ).

Our means for the proof of the Riemann hypothesis in present article are more conventional and “old-fashioned” ones, i.e. the Real Analysis and the Theory of Com- plex Functions which were developed already for a long time. The most promising way for a proof of the Riemann hypothesis as it seemed to us in past is via the already mentioned entire function ![]() which is closely related to the Riemann zeta function

which is closely related to the Riemann zeta function![]() . It contains all important elements and information of the last but excludes its trivial zeros and its only singularity and, moreover, possesses remarkable symmetries which facilitate the work with it compared with the Riemann zeta function. This function

. It contains all important elements and information of the last but excludes its trivial zeros and its only singularity and, moreover, possesses remarkable symmetries which facilitate the work with it compared with the Riemann zeta function. This function ![]() was already introduced by Riemann [1] and dealt with, for example, in the classical books of Titchmarsh [3] , Edwards [5] and in almost all of the sources cited at the beginning. Present article is mainly concerned with this xi function

was already introduced by Riemann [1] and dealt with, for example, in the classical books of Titchmarsh [3] , Edwards [5] and in almost all of the sources cited at the beginning. Present article is mainly concerned with this xi function ![]() and

and

its investigation in which, for convenience, we displace the imaginary axis by ![]() to the

to the

right that means to the critical line and call this Xi function ![]() with

with![]() . We derive some representations for it among them novel ones and discuss its properties, including its derivatives, its specialization to the critical line and some other features. We make an approach to this function via the second mean value theorem of analysis (Gauss-Bonnet theorem, e.g., [37] [38] ) and then we apply an operator identity for analytic functions which is derived in Appendix B and which is equivalent to a somehow integrated form of the Cauchy-Riemann equations. This among other not so successful trials (e.g., via moments of function

. We derive some representations for it among them novel ones and discuss its properties, including its derivatives, its specialization to the critical line and some other features. We make an approach to this function via the second mean value theorem of analysis (Gauss-Bonnet theorem, e.g., [37] [38] ) and then we apply an operator identity for analytic functions which is derived in Appendix B and which is equivalent to a somehow integrated form of the Cauchy-Riemann equations. This among other not so successful trials (e.g., via moments of function![]() ) led us finally to a proof of the Riemann hypothesis embedded into a proof for a more general class of functions.

) led us finally to a proof of the Riemann hypothesis embedded into a proof for a more general class of functions.

Our approach to a proof of the Riemann hypothesis in this article in rough steps is as follows:

First we shortly represent the transition from the Riemann zeta function ![]() of complex variable

of complex variable ![]() to the xi function

to the xi function ![]() introduced already by Riemann and derive for it by means of the Poisson summation formula a representation which is convergent in the whole complex plane (Section 2 with main formal part in Appendix

introduced already by Riemann and derive for it by means of the Poisson summation formula a representation which is convergent in the whole complex plane (Section 2 with main formal part in Appendix

A). Then we displace the imaginary axis of variable ![]() to the critical line at

to the critical line at ![]() by

by ![]() that is purely for convenience of further working with the formulae.

that is purely for convenience of further working with the formulae.

However, this has also the desired subsidiary effect that it brings us into the fairway of the complex analysis usually represented with the complex variable![]() . The transformed

. The transformed ![]() function is called

function is called ![]() function.

function.

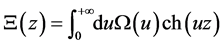

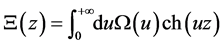

The function ![]() is represented as an integral transform of a real-valued function

is represented as an integral transform of a real-valued function

![]() of the real variable

of the real variable ![]() in the form

in the form ![]() which is related

which is related

to a Fourier transform (more exactly to Cosine Fourier transform). If the Riemann hypothesis is true then we have to prove that all zeros of the function ![]() occur for

occur for![]() .

.

To the Xi function in mentioned integral transform we apply the second mean-value theorem of real analysis first on the imaginary axes and discuss then its extension from the imaginary axis to the whole complex plane. For this purpose we derive in Appendix B in operator form general relations which allow to extend a holomorphic function from the values on the imaginary axis (or also real axis) to the whole complex plane which are equivalents in integral form to the Cauchy-Riemann equations in differential form and apply this in specific form to the Xi function and, more precisely, to the mean-value function on the imaginary axis (Sections 3 and 4).

Then in Section 5 we accomplish the proof with the discussion and solution of the two most important equations (10) and (11) for the last as decisive stage of the proof. These two equations are derived in preparation before this last stage of the proof. From these equations it is seen that the obtained two real equations admit zeros of the Xi function only on the imaginary axis. This proves the Riemann hypothesis by the equivalence of the Riemann zeta function ![]() to the Xi function

to the Xi function ![]() and embeds it into a whole class of functions with similar properties and positions of their zeros.

and embeds it into a whole class of functions with similar properties and positions of their zeros.

The Sections 6-7 serve for illustrations and graphical representations of the specific parameters (e.g., mean-value parameters) for the Xi function to the Riemann hy- pothesis and for other functions which in our proof by the second mean-value problem are included for the existence of zeros only on the imaginary axis. This is, in particular,

also the whole class of modified Bessel functions ![]() with real

with real

indices ![]() which possess zeros only on the imaginary axis

which possess zeros only on the imaginary axis ![]() and where a proof by means of the differential equations exists and certain classes of almost-periodic functions. We intend to present this last topics in detail in future.

and where a proof by means of the differential equations exists and certain classes of almost-periodic functions. We intend to present this last topics in detail in future.

2. From Riemann Zeta Function ![]() to Related Xi Function

to Related Xi Function ![]() and Its Argument Displacement to Function

and Its Argument Displacement to Function ![]()

In this Section we represent the known transition from the Riemann zeta function ![]() to a function

to a function ![]() and finally to a function

and finally to a function ![]() with displaced complex

with displaced complex

variable ![]() for rational effective work and establish some of the basic

for rational effective work and establish some of the basic

representations of these functions, in particular, a kind of modified Cosine Fourier transformations of a function ![]() to the function

to the function![]() .

.

As already expressed in the Introduction, the most promising way for a proof of the Riemann hypothesis as it seems to us is the way via a certain integral representation of the related xi function![]() . We sketch here the transition from the Riemann zeta function

. We sketch here the transition from the Riemann zeta function ![]() to the related xi function

to the related xi function ![]() in a short way because, in principle, it is known and we delegate some aspects of the derivations to Appendix A.

in a short way because, in principle, it is known and we delegate some aspects of the derivations to Appendix A.

Usually, the starting point for the introduction of the Riemann zeta function ![]() is the following relation between the Euler product and an infinite series continued to the whole complex

is the following relation between the Euler product and an infinite series continued to the whole complex ![]() -plane

-plane

![]() (2.1)

(2.1)

where ![]() denotes the ordered sequence of primes (

denotes the ordered sequence of primes (![]() ). The transition from the product formula to the sum representation in (2.1) via transition to

). The transition from the product formula to the sum representation in (2.1) via transition to

the Logarithm of ![]() and Taylor series expansion of the factors

and Taylor series expansion of the factors ![]() in

in

powers of ![]() using the uniqueness of the prime-number decomposition is well

using the uniqueness of the prime-number decomposition is well

known and due to Euler in 1737. It leads to a special case of a kind of series later introduced and investigated in more general form and called Dirichlet series. The Riemann zeta function ![]() can be analytically continued into the whole complex plane to a meromorphic function that was made and used by Riemann. The sum in (2.1) converges uniformly for complex variable

can be analytically continued into the whole complex plane to a meromorphic function that was made and used by Riemann. The sum in (2.1) converges uniformly for complex variable ![]() in the open semi-planes with arbitrary

in the open semi-planes with arbitrary ![]() and arbitrary

and arbitrary![]() . The only singularity of the function

. The only singularity of the function ![]() is a simple pole at

is a simple pole at ![]() with residue 1 that we discuss below.

with residue 1 that we discuss below.

The product form (2.1) of the zeta function ![]() shows that it involves all prime numbers

shows that it involves all prime numbers ![]() exactly one times and therefore it contains information about them in a coded form. It proves to be possible to regain information about the prime number distribution from this function. For many purposes it is easier to work with mero- morphic and, moreover, entire functions than with infinite sequences of numbers but in first case one has to know the properties of these functions which are determined by their zeros and their singularities together with their multiplicity.

exactly one times and therefore it contains information about them in a coded form. It proves to be possible to regain information about the prime number distribution from this function. For many purposes it is easier to work with mero- morphic and, moreover, entire functions than with infinite sequences of numbers but in first case one has to know the properties of these functions which are determined by their zeros and their singularities together with their multiplicity.

From the well-known integral representation of the Gamma function

![]() (2.2)

(2.2)

follows by the substitutions ![]() with an appropriately fixed parameter

with an appropriately fixed parameter ![]() for arbitrary natural numbers

for arbitrary natural numbers ![]()

![]() (2.3)

(2.3)

Inserting this into the sum representation (2.1) and changing the order of summation and integration, we obtain for choice ![]() of the parameter using the sum evaluation of the geometric series

of the parameter using the sum evaluation of the geometric series

![]() (2.4)

(2.4)

and for choice ![]() with substitution

with substitution ![]() of the integration variable (see [1] and, e.g., [3] [4] [5] [7] [9] )

of the integration variable (see [1] and, e.g., [3] [4] [5] [7] [9] )

![]() (2.5)

(2.5)

Other choice of ![]() seems to be of lesser importance. Both representations (2.4) and (2.5) are closely related to a Mellin transform

seems to be of lesser importance. Both representations (2.4) and (2.5) are closely related to a Mellin transform ![]() of a function

of a function ![]() which together with its inversion is generally defined by (e.g., [15] [32] [33] [34] [35] )

which together with its inversion is generally defined by (e.g., [15] [32] [33] [34] [35] )

![]() (2.6)

(2.6)

where ![]() is an arbitrary real value within the convergence strip of

is an arbitrary real value within the convergence strip of ![]() in complex

in complex ![]() -plane. The Mellin transform

-plane. The Mellin transform ![]() of a function

of a function ![]() is closely related to the Fourier transform

is closely related to the Fourier transform ![]() of the function

of the function ![]() by variable substitution

by variable substitution ![]() and

and![]() . Thus the Riemann zeta function

. Thus the Riemann zeta function ![]() can be represented, substantially (i.e., up to factors depending on

can be represented, substantially (i.e., up to factors depending on![]() ), as the Mellin transforms of the

), as the Mellin transforms of the

functions ![]() or of

or of![]() , respectively. The

, respectively. The

kernels of the Mellin transform are the eigenfunctions of the differential operator

![]() to eigenvalue

to eigenvalue ![]() or, correspondingly, of the integral operator

or, correspondingly, of the integral operator ![]()

of the multiplication of the argument of a function by a factor ![]() (scaling of argument). Both representations (2.4) and (2.5) can be used for the derivation of further representations of the Riemann zeta function and for the analytic continuation. The analytic continuation of the Riemann zeta function can also be obtained using the Euler-Maclaurin summation formula for the series in (2.1) (e.g., [5] [11] [15] ).

(scaling of argument). Both representations (2.4) and (2.5) can be used for the derivation of further representations of the Riemann zeta function and for the analytic continuation. The analytic continuation of the Riemann zeta function can also be obtained using the Euler-Maclaurin summation formula for the series in (2.1) (e.g., [5] [11] [15] ).

Using the Poisson summation formula, one can transform the representation (2.5) of the Riemann zeta function to the following form

![]() (2.7)

(2.7)

This is known [1] [3] [5] [7] [9] but for convenience and due to the importance of this representation for our purpose we give a derivation in Appendix A. From (2.7) which is now already true for arbitrary complex ![]() and, therefore, is an analytic continuation of the representations (2.1) or (2.5) we see that the Riemann zeta function satisfies a functional equation for the transformation of the argument

and, therefore, is an analytic continuation of the representations (2.1) or (2.5) we see that the Riemann zeta function satisfies a functional equation for the transformation of the argument![]() . In simplest form it appears by “renormalizing” this function via introduction of the xi function

. In simplest form it appears by “renormalizing” this function via introduction of the xi function ![]() defined by Riemann according to [1] and to [5] [20] 1

defined by Riemann according to [1] and to [5] [20] 1

![]() (2.8)

(2.8)

and we obtain for it the following representation converging in the whole complex plane of ![]() (e.g., [1] [4] [5] [7] [9] )

(e.g., [1] [4] [5] [7] [9] )

![]() (2.9)

(2.9)

with the “normalization”

![]() (2.10)

(2.10)

For ![]() the xi function and the zeta function possess the (likely transcendental)

the xi function and the zeta function possess the (likely transcendental)

values

![]() (2.11)

(2.11)

Contrary to the Riemann zeta function ![]() the function

the function ![]() is an entire function. The only singularity of

is an entire function. The only singularity of ![]() which is the simple pole at

which is the simple pole at![]() , is removed by multiplication of

, is removed by multiplication of ![]() with

with ![]() in the definition (2.8) and the trivial zeros of

in the definition (2.8) and the trivial zeros of ![]() at

at ![]() are also removed by its multiplication with

are also removed by its multiplication with

![]() which possesses simple poles there.

which possesses simple poles there.

The functional equation

![]() (2.12)

(2.12)

from which follows for the ![]() -th derivatives

-th derivatives

![]() (2.13)

(2.13)

and which expresses that ![]() is a symmetric function with respect to

is a symmetric function with respect to ![]() as it is

as it is

immediately seen from (2.9) and as it was first derived by Riemann [1] . It can be easily converted into the following functional equation for the Riemann zeta function ![]() 2

2

![]() (2.14)

(2.14)

Together with ![]() we find by combination with (2.12)

we find by combination with (2.12)

![]() (2.15)

(2.15)

that combine in simple way, function values for 4 points ![]() of the complex plane. Relation (15) means that in contrast to the function

of the complex plane. Relation (15) means that in contrast to the function ![]() which is only real-valued on the real axis the function

which is only real-valued on the real axis the function ![]() becomes real-valued on the real

becomes real-valued on the real

axis (![]() ) and on the imaginary axis (

) and on the imaginary axis (![]() ).

).

As a consequence of absent zeros of the Riemann zeta function ![]() for

for ![]() together with the functional relation (14) follows that all nontrivial zeros of this function have to be within the strip

together with the functional relation (14) follows that all nontrivial zeros of this function have to be within the strip ![]() and the Riemann hypothesis asserts that all zeros of the related xi function

and the Riemann hypothesis asserts that all zeros of the related xi function ![]() are positioned on the

are positioned on the

so-called critical line![]() . This is, in principle, well known.

. This is, in principle, well known.

We use the functional Equation (2.12) for a simplification of the notations in the following considerations and displace the imaginary axis of the complex variable

![]() from

from ![]() to the value

to the value ![]() by introducing the entire function

by introducing the entire function ![]()

of the complex variable ![]() as follows

as follows

![]() (2.16)

(2.16)

with the “normalization” (see (2.10) and (2.11))

![]() (2.17)

(2.17)

following from (2.10). Thus the full relation of the Xi function ![]() to the Riemann zeta function

to the Riemann zeta function ![]() using definition (2.8) is

using definition (2.8) is

![]() (2.18)

(2.18)

We emphasize again that the argument displacement (2.16) is made in the following only for convenience of notations and not for some more principal reason.

The functional equation (2.12) together with (2.13) becomes

![]() (2.19)

(2.19)

and taken together with the symmetry for the transition to complex conjugated variable

![]() (2.20)

(2.20)

This means that the Xi function ![]() becomes real-valued on the imaginary axis

becomes real-valued on the imaginary axis ![]() which becomes the critical line in the new variable

which becomes the critical line in the new variable ![]()

![]() (2.21)

(2.21)

Furthermore, the function ![]() becomes a symmetrical function and a real-valued one on the real axis

becomes a symmetrical function and a real-valued one on the real axis ![]()

![]() (2.22)

(2.22)

In contrast to this the Riemann zeta function ![]() the function is not a real-valued

the function is not a real-valued

function on the critical line ![]() and is real-valued but not symmetric on the real

and is real-valued but not symmetric on the real

axis. This is represented in Figure 1. (calculated with “Mathematica 6” such as the

further figures too). We see that not all of the zeros of the real part ![]() are also zeros of the imaginary part

are also zeros of the imaginary part ![]() and, vice versa, that not all of the

and, vice versa, that not all of the

zeros of the imaginary part are also zeros of the real part and thus genuine zeros of the

function ![]() which are signified by grid lines. Between two zeros of the real part which are genuine zeros of

which are signified by grid lines. Between two zeros of the real part which are genuine zeros of ![]() lies in each case (exception first interval)

lies in each case (exception first interval)

an additional zero of the imaginary part, which almost coincides with a maximum of the real part.

![]()

Figure 1. Real and imaginary part and absolute value of Riemann zeta function on critical line. The position of the zeros of the whole function ![]() on the critical line are shown by grid lines. One can see that not all zeros of the real part are also zeros of the imaginary part and vice versa. The figures are easily to generate by program “Mathematica” and are published in similar forms already in literature.

on the critical line are shown by grid lines. One can see that not all zeros of the real part are also zeros of the imaginary part and vice versa. The figures are easily to generate by program “Mathematica” and are published in similar forms already in literature.

Using (2.9) and definition (2.16) we find the following representation of ![]()

![]() (2.23)

(2.23)

With the substitution of the integration variable ![]() (see also (2.10) in Appendix A) representation (2.23) is transformed to

(see also (2.10) in Appendix A) representation (2.23) is transformed to

![]() (2.24)

(2.24)

In Appendix A we show that (2.24) can be represented as follows (see also Equation (2.2) on p. 17 in [5] which possesses a similar principal form)

![]() (2.25)

(2.25)

with the following explicit form of the function ![]() of the real variable

of the real variable ![]()

![]() (2.26)

(2.26)

The function ![]() is symmetric

is symmetric

![]() (2.27)

(2.27)

that means it is an even function although this is not immediately seen from representation (2.26)3. We prove this in Appendix A. Due to this symmetry, formula (2.25) can be also represented by

![]() (2.28)

(2.28)

In the formulation of the right-hand side the function ![]() appears as analytic continuation of the Fourier transform of the function

appears as analytic continuation of the Fourier transform of the function ![]() written with imaginary argument

written with imaginary argument ![]() or, more generally, with substitution

or, more generally, with substitution ![]() and complex

and complex![]() . From this follows as inversion of the integral transformation (2.28) using (2.27)

. From this follows as inversion of the integral transformation (2.28) using (2.27)

![]() (2.29)

(2.29)

or due to symmetry of the integrand in analogy to (2.25)

![]() (2.30)

(2.30)

where ![]() is a real-valued function of the variable

is a real-valued function of the variable ![]() on the imaginary axis

on the imaginary axis

![]() (2.31)

(2.31)

due to (2.25).

A graphical representation of the function ![]() and of its first derivatives

and of its first derivatives ![]() is given in Figure 2. The function

is given in Figure 2. The function ![]() is monotonically de-

is monotonically de-

creasing for ![]() due to the non-positivity of its first derivative

due to the non-positivity of its first derivative ![]()

which explicitly is (see also Appendix A)

![]() (2.32)

(2.32)

with one relative minimum at ![]() of depth

of depth![]() . Moreover, it is very important for the following that due to presence of factors

. Moreover, it is very important for the following that due to presence of factors ![]() in the sum terms in (2.26) or in (2.32) the functions

in the sum terms in (2.26) or in (2.32) the functions ![]() and

and ![]() and all their higher derivatives are very rapidly decreasing for

and all their higher derivatives are very rapidly decreasing for![]() , more rapidly than any exponential function with a polynomial of

, more rapidly than any exponential function with a polynomial of ![]() in the argument. In this sense the function

in the argument. In this sense the function ![]() is more comparable with functions of finite support which vanish from a certain

is more comparable with functions of finite support which vanish from a certain ![]() on than with any exponentially decreasing function. From (2.27) follows immediately that the function

on than with any exponentially decreasing function. From (2.27) follows immediately that the function ![]() is antisymmetric

is antisymmetric

![]() (2.33)

(2.33)

that means it is an odd function.

It is known that smoothness and rapidness of decreasing in infinity of a function change their role in Fourier transformations. As the Fourier transform of the smooth (infinitely continuously differentiable) function ![]() the Xi function on the critical line

the Xi function on the critical line ![]() is rapidly decreasing in infinity. Therefore it is not easy to represent the real-valued function

is rapidly decreasing in infinity. Therefore it is not easy to represent the real-valued function ![]() with its rapid oscillations under the envelope of rapid decrease for increasing variable

with its rapid oscillations under the envelope of rapid decrease for increasing variable ![]() graphically in a large region of this variable

graphically in a large region of this variable![]() . An appropriate real amplification envelope is seen from (2.18) to be

. An appropriate real amplification envelope is seen from (2.18) to be

![]() which rises

which rises ![]() to the level of the Riemann zeta function

to the level of the Riemann zeta function ![]() on the critical line

on the critical line![]() . This is shown in Figure 3. The partial

. This is shown in Figure 3. The partial

picture for ![]() in Figure 3. with negative part folded up is identical with the

in Figure 3. with negative part folded up is identical with the

absolute value ![]() of the Riemann zeta function

of the Riemann zeta function ![]() on the imaginary axis

on the imaginary axis ![]() (fourth partial picture in Figure 1).

(fourth partial picture in Figure 1).

We now give a representation of the Xi function by the derivative of the Omega

function. Using ![]() one obtains from (2.25) by partial integration

one obtains from (2.25) by partial integration

the following alternative representation of the function ![]()

![]() (2.34)

(2.34)

that due to antisymmetry of ![]() and

and ![]() with respect to

with respect to ![]() can also be written

can also be written

![]() (2.35)

(2.35)

Figure 2 gives a graphical representation of the function ![]() and of its first

and of its first

derivative ![]() which due to rapid convergence of the sums is easily to

which due to rapid convergence of the sums is easily to

generate by computer. One can express ![]() also by higher derivatives

also by higher derivatives

![]() of the Omega function

of the Omega function ![]() according to

according to

![]() (2.36)

(2.36)

with the symmetries of the derivatives of the function ![]() for

for ![]()

![]() (2.37)

(2.37)

This can be seen by successive partial integrations in (2.25) together with complete induction. The functions ![]() in these integral transformations are for

in these integral transformations are for ![]() not monotonic functions.

not monotonic functions.

We mention yet another representation of the function![]() . Using the trans- formations

. Using the trans- formations

![]() (2.38)

(2.38)

the function ![]() according to (2.28) with the explicit representation of the function

according to (2.28) with the explicit representation of the function ![]() in (2.26) can now be represented in the form

in (2.26) can now be represented in the form

![]() (2.39)

(2.39)

where ![]() denotes the incomplete Gamma function defined by (e.g., [18] [21] [36] )

denotes the incomplete Gamma function defined by (e.g., [18] [21] [36] )

![]() (2.40)

(2.40)

However, we did not see a way to prove the Riemann hypothesis via the repre- sentation (2.39).

The Riemann hypothesis for the zeta function ![]() is now equivalent to the hypothesis that all zeros of the related entire function

is now equivalent to the hypothesis that all zeros of the related entire function ![]() lie on the imaginary axis

lie on the imaginary axis ![]() that means on the line to real part

that means on the line to real part ![]() of

of ![]() which becomes now the critical line. Since the zeta function

which becomes now the critical line. Since the zeta function ![]() does not possess zeros in the convergence region

does not possess zeros in the convergence region ![]() of the Euler product (2.1) and due to symmetries (2.27) and (2.31) it is only necessary to prove that

of the Euler product (2.1) and due to symmetries (2.27) and (2.31) it is only necessary to prove that ![]() does not possess zeros within the

does not possess zeros within the

strips ![]() and

and ![]() to both sides of the imaginary axis

to both sides of the imaginary axis ![]() where

where

for symmetry the proof for one of these strips would be already sufficient. However, we will go another way where the restriction to these strips does not play a role for the proof.

3. Application of Second Mean-Value Theorem of Calculus to Xi Function

After having accepted the basic integral representation (2.25) of the entire function ![]() according to

according to

![]() (3.1)

(3.1)

with the function ![]() explicitly given in (2.26) we concentrate us on its further treatment. However, we do this not with this specialization for the real-valued function

explicitly given in (2.26) we concentrate us on its further treatment. However, we do this not with this specialization for the real-valued function ![]() but with more general suppositions for it. Expressed by real part

but with more general suppositions for it. Expressed by real part ![]() and imaginary part

and imaginary part ![]() of

of ![]()

![]() (3.2)

(3.2)

we find from (3.1)

![]() (3.3)

(3.3)

We suppose now as necessary requirement for ![]() and satisfied in the special case (2.26)

and satisfied in the special case (2.26)

![]() (3.4)

(3.4)

Furthermore, ![]() should be an entire function that requires that the integral (3.1) is finite for arbitrary complex

should be an entire function that requires that the integral (3.1) is finite for arbitrary complex ![]() and therefore that

and therefore that ![]() is rapidly decreasing in infinity, more precisely

is rapidly decreasing in infinity, more precisely

![]() (3.5)

(3.5)

for arbitrary![]() . This means that the function

. This means that the function ![]() should be a nonsingular function which is rapidly decreasing in infinity, more rapidly than any exponential function

should be a nonsingular function which is rapidly decreasing in infinity, more rapidly than any exponential function ![]() with arbitrary

with arbitrary![]() . Clearly, this is satisfied for the special function

. Clearly, this is satisfied for the special function ![]() in (2.26).

in (2.26).

Our conjecture for a longer time was that all zeros of ![]() lie on the imaginary axis

lie on the imaginary axis ![]() for a large class of functions

for a large class of functions ![]() and that this is not very specific for the special function

and that this is not very specific for the special function ![]() given in (2.26) but is true for a much larger class. It seems that to this class belong all non-increasing functions

given in (2.26) but is true for a much larger class. It seems that to this class belong all non-increasing functions![]() , i.e such functions for which holds

, i.e such functions for which holds ![]() for its first derivative and which rapidly decrease in infinity. This means that they vanish more rapidly in infinity than any power functions

for its first derivative and which rapidly decrease in infinity. This means that they vanish more rapidly in infinity than any power functions ![]() (practically they vanish exponentially). However, for the conver- gence of the integral (3.1) in the whole complex

(practically they vanish exponentially). However, for the conver- gence of the integral (3.1) in the whole complex ![]() -plane it is necessary that the functions have to decrease in infinity also more rapidly than any exponential function

-plane it is necessary that the functions have to decrease in infinity also more rapidly than any exponential function ![]() with arbitrary

with arbitrary ![]() expressed in (3.5). In particular, to this class belong all rapidly decreasing functions

expressed in (3.5). In particular, to this class belong all rapidly decreasing functions ![]() which vanish from a certain

which vanish from a certain ![]() on and which may be called non-increasing finite functions (or functions with compact support). On the other side, continuity of its derivatives

on and which may be called non-increasing finite functions (or functions with compact support). On the other side, continuity of its derivatives ![]() is not required. The modified Bessel functions

is not required. The modified Bessel functions ![]() “normalized” to the form of entire

“normalized” to the form of entire

functions ![]() for

for ![]() possess a representation of the form (3.1) with

possess a representation of the form (3.1) with

functions ![]() which vanish from

which vanish from ![]() on but a number of derivatives of

on but a number of derivatives of ![]() for the functions is not continuous at

for the functions is not continuous at ![]() depending on the index

depending on the index![]() . It is valuable that here an independent proof of the property that all zeros of the modified Bessel functions

. It is valuable that here an independent proof of the property that all zeros of the modified Bessel functions ![]() lie on the imaginary axis can be made using their differential eq- uations via duality relations. We intend to present this in detail in a later work.

lie on the imaginary axis can be made using their differential eq- uations via duality relations. We intend to present this in detail in a later work.

Furthermore, to the considered class belong all monotonically decreasing functions with the described rapid decrease in infinity. The fine difference of the decreasing functions to the non-increasing functions ![]() is that in first case the function

is that in first case the function ![]() cannot stay on the same level in a certain interval that means we have

cannot stay on the same level in a certain interval that means we have ![]() for all points

for all points ![]() instead of

instead of ![]() only. A function which de- creases not faster than

only. A function which de- creases not faster than ![]() in infinity does not fall into this category as, for example,

in infinity does not fall into this category as, for example,

the function ![]() shows.

shows.

To apply the second mean-value theorem it is necessary to restrict us to a class of functions ![]() which are non-increasing that means for which for all

which are non-increasing that means for which for all ![]() in considered interval holds

in considered interval holds

![]() (3.6)

(3.6)

or equivalently in more compact form

![]() (3.7)

(3.7)

The monotonically decreasing functions in the interval![]() , in particular, belong to the class of non-increasing functions with the fine difference that here

, in particular, belong to the class of non-increasing functions with the fine difference that here

![]() (3.8)

(3.8)

is satisfied. Thus smoothness of ![]() for

for ![]() is not required. If furthermore

is not required. If furthermore ![]() is a continuous function in the interval

is a continuous function in the interval ![]() the second mean-value theorem (often called theorem of Bonnet (1867) or Gauss-Bonnet theorem) states an equivalence for the following integral on the left-hand side to the expression on the right-hand side according to (see some monographs about Calculus or Real Analysis; we recommend the monographs of Courant [37] (Appendix to chap IV) and of Widder [38] who called it Weierstrass form of Bonnet’s theorem (chap. 5,

the second mean-value theorem (often called theorem of Bonnet (1867) or Gauss-Bonnet theorem) states an equivalence for the following integral on the left-hand side to the expression on the right-hand side according to (see some monographs about Calculus or Real Analysis; we recommend the monographs of Courant [37] (Appendix to chap IV) and of Widder [38] who called it Weierstrass form of Bonnet’s theorem (chap. 5, ![]() 4))

4))

![]() (3.9)

(3.9)

where ![]() is a certain value within the interval boundaries

is a certain value within the interval boundaries ![]() which as a rule we do not exactly know. It holds also for non-decreasing functions which include the monotonically increasing functions as special class in analogous way. The proof of the second mean-value theorem is comparatively simple by applying a substitution in the (first) mean-value theorem of integral calculus [37] [38] .

which as a rule we do not exactly know. It holds also for non-decreasing functions which include the monotonically increasing functions as special class in analogous way. The proof of the second mean-value theorem is comparatively simple by applying a substitution in the (first) mean-value theorem of integral calculus [37] [38] .

Applied to our function ![]() which in addition should rapidly decrease in infinity according to (3.5) this means in connection with monotonic decrease that it has to be positively semi-definite if

which in addition should rapidly decrease in infinity according to (3.5) this means in connection with monotonic decrease that it has to be positively semi-definite if ![]() and therefore

and therefore

![]() (3.10)

(3.10)

and the theorem (3.9) takes on the form

![]() (3.11)

(3.11)

where the extension to an upper boundary ![]() in (3.9) for

in (3.9) for ![]() and in case of existence of the integral is unproblematic.

and in case of existence of the integral is unproblematic.

If we insert in (3.9) for ![]() the function

the function ![]() which apart from the real variable

which apart from the real variable ![]() depends in parametrical way on the complex variable

depends in parametrical way on the complex variable ![]() and is an analytic function of

and is an analytic function of ![]() we find that

we find that ![]() depends on this complex parameter also in an analytic way as follows

depends on this complex parameter also in an analytic way as follows

![]() (3.12)

(3.12)

where ![]() is an entire function with

is an entire function with ![]() its real and

its real and ![]() its imaginary part. The condition for zeros

its imaginary part. The condition for zeros ![]() is that

is that ![]() vanishes that leads to

vanishes that leads to

![]() (3.13)

(3.13)

or split in real and imaginary part

![]() (3.14)

(3.14)

for the real part and

![]() (3.15)

(3.15)

for the imaginary part.

The multi-valuedness of the mean-value functions in the conditions (3.13) or (3.15) is an interesting phenomenon which is connected with the periodicity of the function ![]() on the imaginary axis

on the imaginary axis ![]() in our application (3.12) of the second mean-value theorem (3.11). To our knowledge this is up to now not well studied. We come back to this in the next Sections 4 and, in particular, Section 7 brings some illustrative clarity when we represent the mean-value functions graphically. At present we will say only that we can choose an arbitrary

in our application (3.12) of the second mean-value theorem (3.11). To our knowledge this is up to now not well studied. We come back to this in the next Sections 4 and, in particular, Section 7 brings some illustrative clarity when we represent the mean-value functions graphically. At present we will say only that we can choose an arbitrary ![]() in (3.15) which provides us the whole spectrum of zeros

in (3.15) which provides us the whole spectrum of zeros ![]() on the upper half-plane and the corresponding spectrum of zeros

on the upper half-plane and the corresponding spectrum of zeros ![]() on the lower half-plane of

on the lower half-plane of ![]() which as will be later seen lie all on the imaginary axis. Since in computer calculations the values of

which as will be later seen lie all on the imaginary axis. Since in computer calculations the values of

the Arcus Sine function are provided in the region from ![]() to

to ![]() it is convenient

it is convenient

to choose ![]() but all other values of

but all other values of ![]() in (3.15) lead to equivalent results.

in (3.15) lead to equivalent results.

One may represent the conditions (3.14) and (3.15) also in the following equivalent form

![]() (3.16)

(3.16)

from which follows

![]() (3.17)

(3.17)

All these forms (3.14)-(3.17) are implicit equations with two variables ![]() which cannot be resolved with respect to one variable (e.g., in forms

which cannot be resolved with respect to one variable (e.g., in forms ![]() for each fixed

for each fixed ![]() and branches

and branches![]() ) and do not provide immediately the necessary conditions for zeros in explicit form but we can check that (3.16) satisfies the Cauchy-Riemann equations as a minimum requirement

) and do not provide immediately the necessary conditions for zeros in explicit form but we can check that (3.16) satisfies the Cauchy-Riemann equations as a minimum requirement

![]() (3.18)

(3.18)

We have to establish now closer relations between real and imaginary part ![]() and

and ![]() of the complex mean-value parameter

of the complex mean-value parameter![]() . The first step in preparation to this aim is the consideration of the derived conditions on the imaginary axis.

. The first step in preparation to this aim is the consideration of the derived conditions on the imaginary axis.

4. Specialization of Second Mean-Value Theorem to Xi Function on Imaginary Axis

By restriction to the real axis ![]() we find from (3.3) for the function

we find from (3.3) for the function ![]()

![]() (4.1)

(4.1)

with the following two possible representations of ![]() related by partial in- tegration

related by partial in- tegration

![]() (4.2)

(4.2)

The inequality ![]() follows according to the supposition

follows according to the supposition ![]() from the non-negativity of the integrand that means from

from the non-negativity of the integrand that means from![]() . Therefore, the case

. Therefore, the case ![]() can be excluded from the beginning in the further considerations for zeros of

can be excluded from the beginning in the further considerations for zeros of ![]() and

and![]() .

.

We now restrict us to the imaginary axis ![]() and find from (3.3) for the function

and find from (3.3) for the function ![]()

![]() (4.3)

(4.3)

with the following two possible representations of ![]() related by partial in- tegration

related by partial in- tegration

![]() (4.4)

(4.4)

From the obvious inequality

![]() (4.5)

(4.5)

together with the supposed positivity of ![]() one derives from the first repre- sentation of

one derives from the first repre- sentation of ![]() in (4) the inequality

in (4) the inequality

![]() (4.6)

(4.6)

In the same way by the inequality

![]() (4.7)

(4.7)

one derives using the non-positivity of ![]() (see (3.10)) together with the second representation of

(see (3.10)) together with the second representation of ![]() in (4.4) the inequality

in (4.4) the inequality

![]() (4.8)

(4.8)

which as it is easily seen does not depend on the sign of![]() . Therefore we have two non-negative parameters, the zeroth moment

. Therefore we have two non-negative parameters, the zeroth moment ![]() and the value

and the value![]() , which according to (4.6) and (4.8) restrict the range of values of

, which according to (4.6) and (4.8) restrict the range of values of ![]() to an interior range both to (4.6) and to (4.8) at once.

to an interior range both to (4.6) and to (4.8) at once.

For mentioned purpose we now consider the restriction of the mean-value parameter ![]() to the imaginary axis

to the imaginary axis ![]() for which

for which ![]() is a real- valued function of

is a real- valued function of![]() . For arbitrary fixed

. For arbitrary fixed ![]() we find by the second mean-value theorem a parameter

we find by the second mean-value theorem a parameter ![]() in the interval

in the interval ![]() which naturally depends on the chosen value

which naturally depends on the chosen value ![]() that means

that means![]() . The extension from the imaginary axis

. The extension from the imaginary axis ![]() to the whole complex plane

to the whole complex plane ![]() can be made then using methods of complex analysis. We discuss some formal approaches to this in Appendix B. Now we apply (3.12) to the imaginary axis

can be made then using methods of complex analysis. We discuss some formal approaches to this in Appendix B. Now we apply (3.12) to the imaginary axis![]() .

.

The second mean-value theorem (3.12) on the imaginary axis ![]() (or

(or![]() ) takes on the form

) takes on the form

![]() (4.9)

(4.9)

As already said since the left-hand side is a real-valued function the right-hand side has also to be real-valued and the parameter function ![]() is real-valued and there- fore it can only be the real part

is real-valued and there- fore it can only be the real part ![]() of the complex function

of the complex function ![]() for

for![]() .

.

The second mean-value theorem states that ![]() lies between the minimal and maximal values of the integration borders that is here between 0 and

lies between the minimal and maximal values of the integration borders that is here between 0 and ![]() and this means that

and this means that ![]() should be positive. Here arises a problem which is connected with the periodicity of the function

should be positive. Here arises a problem which is connected with the periodicity of the function ![]() as function of the variable

as function of the variable ![]() for fixed variable

for fixed variable ![]() in the application of the mean-value theorem. Let us first consider the special case

in the application of the mean-value theorem. Let us first consider the special case ![]() in (4.9) which leads to

in (4.9) which leads to

![]() (4.10)

(4.10)

From this relation follows ![]() and it seems that all is correct also with the continuation to

and it seems that all is correct also with the continuation to ![]() for arbitrary

for arbitrary![]() . One may even give the approximate values

. One may even give the approximate values ![]() and

and ![]() and therefore

and therefore ![]() which, however, are not of importance for the later proofs. If we now start from

which, however, are not of importance for the later proofs. If we now start from ![]() and continue it continuously to

and continue it continuously to ![]() then we see that

then we see that ![]() goes monotonically to zero and approaches zero approximately at

goes monotonically to zero and approaches zero approximately at ![]() that is at the first zero of the function

that is at the first zero of the function ![]() on the positive imaginary axis and goes then first beyond zero and oscillates then with decreasing amplitude for increasing

on the positive imaginary axis and goes then first beyond zero and oscillates then with decreasing amplitude for increasing ![]() around the value zero with intersecting it exactly at the zeros of

around the value zero with intersecting it exactly at the zeros of![]() . We try to illustrate this graphically in Section 7. All zeros lie then on the branch

. We try to illustrate this graphically in Section 7. All zeros lie then on the branch ![]() with

with![]() . That

. That ![]() goes beyond zero seems to contradict the content of the second mean-value theorem according which

goes beyond zero seems to contradict the content of the second mean-value theorem according which ![]() has to be positive in our application. Here comes into play the multi-valuedness of the mean-value function

has to be positive in our application. Here comes into play the multi-valuedness of the mean-value function![]() . For the zeros of

. For the zeros of ![]() in (4.9) the relations

in (4.9) the relations ![]() with different integers

with different integers ![]() are equivalent and one may find to values

are equivalent and one may find to values ![]() equivalent curves

equivalent curves ![]() with

with ![]() and all these curves begin with

and all these curves begin with ![]() for

for![]() . However, we cannot continue

. However, we cannot continue ![]() in continuous way to only positive values for

in continuous way to only positive values for![]() .

.

For ![]() the inequality (4.8) is stronger than (4.6) and characterizes the restric- tions of

the inequality (4.8) is stronger than (4.6) and characterizes the restric- tions of ![]() and via the equivalence

and via the equivalence ![]() follows from (4.8)

follows from (4.8)

![]() (4.11)

(4.11)

where the choice of ![]() determines a basis interval of the involved multi-valued function

determines a basis interval of the involved multi-valued function ![]() and the inequality says that it is in every case possible to choose it from the same interval of length

and the inequality says that it is in every case possible to choose it from the same interval of length![]() . The zeros

. The zeros ![]() of the Xi function

of the Xi function ![]() on the imaginary axis

on the imaginary axis ![]() (critical line) are determined alone by the (multi-valued) function

(critical line) are determined alone by the (multi-valued) function ![]() whereas

whereas ![]() vanishes automatically on the imaginary axis in considered special case and does not add a second condition. Therefore, the zeros are the solutions of the conditions

vanishes automatically on the imaginary axis in considered special case and does not add a second condition. Therefore, the zeros are the solutions of the conditions

![]() (4.12)

(4.12)

It is, in general, not possible to obtain the zeros ![]() on the critical line exactly from the mean-value function

on the critical line exactly from the mean-value function ![]() in (4.9) since generally we do not possess it ex- plicitly.

in (4.9) since generally we do not possess it ex- plicitly.

In special cases the function ![]() can be calculated explicitly that is the case, for

can be calculated explicitly that is the case, for

example, for all (modified) Bessel functions![]() . The most simple case among these is the case

. The most simple case among these is the case ![]() when the corresponding function

when the corresponding function ![]() is a step function

is a step function

![]() (4.13)

(4.13)

where ![]() is the Heaviside step function. In this case follows

is the Heaviside step function. In this case follows

![]() (4.14)

(4.14)

where ![]() is the area under the function

is the area under the function ![]()

(or the zeroth-order moment of this function. For the squared modulus of the function ![]() we find

we find

![]() (4.15)

(4.15)

from which, in particular, it is easy to see that this special function ![]() possesses zeros only on the imaginary axis

possesses zeros only on the imaginary axis ![]() or

or ![]() and that they are determined by

and that they are determined by

![]() (4.16)

(4.16)

The zeros on the imaginary axis are here equidistant but the solution ![]() is absent since then also the denominators in (4.15) are vanishing. The parameter

is absent since then also the denominators in (4.15) are vanishing. The parameter ![]() in the second mean-value theorem is here a real constant

in the second mean-value theorem is here a real constant ![]() in the whole complex plane

in the whole complex plane

![]() (4.17)

(4.17)

Practically, the second mean-value theorem compares the result for an arbitrary function ![]() under the given restrictions with that for a step function

under the given restrictions with that for a step function ![]() by preserving the value

by preserving the value ![]() and making the parameter

and making the parameter ![]() depending on

depending on ![]() in the whole complex plane. Without discussing now quantitative relations the formulae (4.17) suggest that

in the whole complex plane. Without discussing now quantitative relations the formulae (4.17) suggest that ![]() will stay a “small” function compared with

will stay a “small” function compared with ![]() in the neighborhood of the imaginary axis (i.e. for

in the neighborhood of the imaginary axis (i.e. for![]() ) in a certain sense.

) in a certain sense.

We will see in next Section that the function ![]() taking into account

taking into account ![]() determines the functions

determines the functions ![]() and

and ![]() and thus

and thus ![]() in the whole complex plane via the Cauchy-Riemann equations in an operational ap- proach that means in an integrated form which we did not found up to now in literature. The general formal part is again delegated to an Appendix B.

in the whole complex plane via the Cauchy-Riemann equations in an operational ap- proach that means in an integrated form which we did not found up to now in literature. The general formal part is again delegated to an Appendix B.

5. Accomplishment of Proof for Zeros of Xi Functions on Imaginary Axis Alone

In last Section we discussed the application of the second mean-value theorem to the function ![]() on the imaginary axis

on the imaginary axis![]() . Equations (3.14) and (3.15) or their equivalent forms (3.16) or (3.17) are not yet sufficient to derive conclusions about the position of the zeros on the imaginary axis in dependence on

. Equations (3.14) and (3.15) or their equivalent forms (3.16) or (3.17) are not yet sufficient to derive conclusions about the position of the zeros on the imaginary axis in dependence on![]() . We have yet to derive more information about the mean-value functions

. We have yet to derive more information about the mean-value functions ![]() which we obtain by relating the real-valued function

which we obtain by relating the real-valued function ![]() and

and ![]() to the function

to the function ![]() on the imaginary axis taking into account

on the imaginary axis taking into account![]() .

.

The general case of complex ![]() can be obtained from the special case

can be obtained from the special case ![]() in

in

(4.9) by application of the displacement operator ![]() to the function

to the function ![]()

according to

![]() (5.1)

(5.1)

The function ![]() is related to

is related to ![]() as follows

as follows

![]() (5.2)

(5.2)

or in more compact form

![]() (5.3)

(5.3)

This is presented in Appendix B in more general form for additionally non- vanishing ![]() and arbitrary holomorphic functions. It means that we may obtain

and arbitrary holomorphic functions. It means that we may obtain ![]()

and ![]() by applying the operators

by applying the operators ![]() and

and![]() , respectively, to

, respectively, to

the function ![]() on the imaginary axis (remind

on the imaginary axis (remind ![]() vanishes there in our case). Clearly, Equations (5.2) are in agreement with the Cauchy-Riemann eq-

vanishes there in our case). Clearly, Equations (5.2) are in agreement with the Cauchy-Riemann eq-

uations ![]() and

and ![]() as a minimal requirement.

as a minimal requirement.

We now write ![]() in the form equivalent to (5.1)

in the form equivalent to (5.1)

![]() (5.4)

(5.4)

The denominator ![]() does not contribute to zeros. Since the Hyperbolic Sine possesses zeros only on the imaginary axis we see from (5.4) that we may expect zeros only for such related variables

does not contribute to zeros. Since the Hyperbolic Sine possesses zeros only on the imaginary axis we see from (5.4) that we may expect zeros only for such related variables ![]() which satisfy the necessary condition of vanishing of its real part of the argument that leads as we already know to (see (3.14))

which satisfy the necessary condition of vanishing of its real part of the argument that leads as we already know to (see (3.14))

![]() (5.5)

(5.5)

The zeros with coordinates ![]() themselves can be found then as the (in general non-degenerate) solutions of the following equation (see (3.15))

themselves can be found then as the (in general non-degenerate) solutions of the following equation (see (3.15))

![]() (5.6)

(5.6)

if these pairs ![]() satisfy the necessary condition (5.5). Later we will see that it provides the whole spectrum of solutions for the zeros but we can also obtain each

satisfy the necessary condition (5.5). Later we will see that it provides the whole spectrum of solutions for the zeros but we can also obtain each ![]() separately from one branch

separately from one branch ![]() and would they then denote by

and would they then denote by![]() . Thus we have first of all to look for such pairs

. Thus we have first of all to look for such pairs ![]() which satisfy the condition (5.5) off the imaginary axis that is for

which satisfy the condition (5.5) off the imaginary axis that is for ![]() since we know already that these functions may possess zeros on the imaginary axis

since we know already that these functions may possess zeros on the imaginary axis![]() .

.

Using (5.2) we may represent the necessary condition (5.5) for the proof by the second mean-value theorem in the form

![]() (5.7)

(5.7)

and Equation (5.6) which determines then the position of the zeros can be written with equivalent values ![]()

![]() (5.8)

(5.8)

We may represent Equations (5.7) and (5.8) in a simpler form using the following operational identities

![]() (5.9)

(5.9)

which are a specialization of the operational identities (B.11) in Appendix B with ![]() and therefore

and therefore![]() . If we multiply (5.7) and (5.8) both by the function

. If we multiply (5.7) and (5.8) both by the function ![]() then we may write (5.7) in the form (changing order

then we may write (5.7) in the form (changing order![]() )

)

![]() (5.10)

(5.10)

and (5.8) in the form

![]() (5.11)

(5.11)

The left-hand side of these conditions possess the general form for the extension of a holomorphic function ![]() from the functions

from the functions ![]() and

and ![]() on the imaginary axis to the whole complex plane in case of

on the imaginary axis to the whole complex plane in case of ![]() and if we apply this to the function

and if we apply this to the function![]() . Equations (5.10) and (5.11) possess now the most simple form, we found, to accomplish the proof for the exclusive position of zeros on the imaginary axis. All information about the zeros of the Xi function

. Equations (5.10) and (5.11) possess now the most simple form, we found, to accomplish the proof for the exclusive position of zeros on the imaginary axis. All information about the zeros of the Xi function ![]() for arbitrary

for arbitrary ![]() is now contained in the conditions (5.10) and (5.11) which we now discuss.

is now contained in the conditions (5.10) and (5.11) which we now discuss.

Since ![]() is a nonsingular operator we can multiply both sides of equation (5.11) by the inverse operator

is a nonsingular operator we can multiply both sides of equation (5.11) by the inverse operator ![]() and obtain

and obtain

![]() (5.12)

(5.12)

This equation is yet fully equivalent to (5.11) for arbitrary ![]() but it provides only the same possible solutions for the values

but it provides only the same possible solutions for the values ![]() of zeros as for zeros on the imaginary axis. This alone already suggests that it cannot be that zeros with

of zeros as for zeros on the imaginary axis. This alone already suggests that it cannot be that zeros with ![]() if they exist possess the same values of

if they exist possess the same values of ![]() as the zeros on the imaginary axis. But in such form the proof of the impossibility of zeros off the imaginary axis seemed to be not satisfactory and we present in the following some slightly different variants which go deeper into the details of the proof.

as the zeros on the imaginary axis. But in such form the proof of the impossibility of zeros off the imaginary axis seemed to be not satisfactory and we present in the following some slightly different variants which go deeper into the details of the proof.

In analogous way by multiplication of (5.10) with the operator ![]() and (5.11) with the operator

and (5.11) with the operator ![]() and addition of both equations we also obtain

and addition of both equations we also obtain

condition (5.12) that means

![]() (5.13)

(5.13)