Advances in Pure Mathematics

Vol.05 No.04(2015), Article ID:54896,33 pages

10.4236/apm.2015.54020

Periodic bifurcations in Descendant Trees of finite p-groups

Daniel C. Mayer

Naglergasse 53, 8010 Graz, Austria

Email: algebraic.number.theory@algebra.at

Copyright © 2015 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 20 February 2015; accepted 13 March 2015; published 23 March 2015

ABSTRACT

Theoretical background and an implementation of the p-group generation algorithm by Newman and O’Brien are used to provide computational evidence of a new type of periodically repeating patterns in pruned descendant trees of finite p-groups.

Keywords:

finite p-Group, Central series, Descendant Tree, pro-p group, coclasstree, p-Covering Group, nuclear Rank, multifurcation, coclass Graph, Parametrized Presentation, commutator Calculus, Schur  -group

-group

1. Introduction

In §§2 - 11, we present an exposition of facts concerning the mathematical structure which forms the central idea of this article: descendant trees of finite p-groups. Their computational construction is recalled in §§12 - 20 on the p-group generation algorithm. Recently periodic patterns have been discovered in descendant trees with promising arithmetical applications form the topic of the final §21 and the coronation of the entire work.

2. Thestructure: Descendant trees

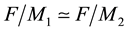

In mathematics, specifically group theory, a descendant tree is a hierarchical structure for visualizing parent- descendant relations (§§4 and 6) between isomorphism classes of finite groups of prime power order , for a fixed prime number

, for a fixed prime number  and varying integer exponents

and varying integer exponents . Such groups are briefly called finite p-groups. The vertices of a descendant tree are isomorphism classes of finite

. Such groups are briefly called finite p-groups. The vertices of a descendant tree are isomorphism classes of finite  -groups.

-groups.

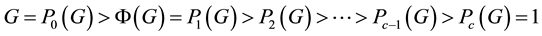

Additionally to their order , finite p-groups possess two further related invariants, the nilpotency class

, finite p-groups possess two further related invariants, the nilpotency class  and the coclass

and the coclass  (§§5 and 8). It turned out that descendant trees of a particular kind, the so-called pruned coclass trees whose infinitely many vertices share a common coclass

(§§5 and 8). It turned out that descendant trees of a particular kind, the so-called pruned coclass trees whose infinitely many vertices share a common coclass , reveal a repeating finite pattern (§7). These two crucial properties of finiteness and periodicity, which have been proved independently by du Sautoy [1] and by Eick and Leedham-Green [2] , admit a characterization of all members of the tree by finitely many parametrized presentations (§§10 and 21). Consequently, descendant trees play a fundamental role in the classification of finite p-groups. By means of kernels and targets of Artin transfer homomorphisms [3] , de- scendant trees can be endowed with additional structure [4] -[6] , which recently turned out to be decisive for ari- thmetical applications in class field theory, in particular, for determining the exact length of p-class towers [7] .

, reveal a repeating finite pattern (§7). These two crucial properties of finiteness and periodicity, which have been proved independently by du Sautoy [1] and by Eick and Leedham-Green [2] , admit a characterization of all members of the tree by finitely many parametrized presentations (§§10 and 21). Consequently, descendant trees play a fundamental role in the classification of finite p-groups. By means of kernels and targets of Artin transfer homomorphisms [3] , de- scendant trees can be endowed with additional structure [4] -[6] , which recently turned out to be decisive for ari- thmetical applications in class field theory, in particular, for determining the exact length of p-class towers [7] .

An important question is how the descendant tree  can actually be constructed for an assigned starting group which is taken as the root

can actually be constructed for an assigned starting group which is taken as the root  of the tree. Sections §§13 - 19 are devoted to recall a minimum of the necessary background concerning the p-group generation algorithm by Newman [8] and O’Brien [9] [10] , which is a recursive process for constructing the descendant tree of a foregiven finite p-group playing the role of the tree root. This algorithm is now implemented in the ANUPQ-package [11] of the computational algebra systems GAP [12] and MAGMA [13] .

of the tree. Sections §§13 - 19 are devoted to recall a minimum of the necessary background concerning the p-group generation algorithm by Newman [8] and O’Brien [9] [10] , which is a recursive process for constructing the descendant tree of a foregiven finite p-group playing the role of the tree root. This algorithm is now implemented in the ANUPQ-package [11] of the computational algebra systems GAP [12] and MAGMA [13] .

As a final highlight in §21, whose formulation requires an understanding of all the preceding sections, this article concludes with brand-new discoveries of an unknown, and up to now unproved, kind of repeating infinite patterns called periodic bifurcations, which appeared in extensive computational constructions of descendant trees of certain finite 2-groups, resp. 3-groups, G with abelianization  of type (2,2,2), resp. (3,3), and have immediate applications in algebraic number theory and class field theory.

of type (2,2,2), resp. (3,3), and have immediate applications in algebraic number theory and class field theory.

3. Historical remarks onbifurcation

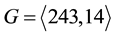

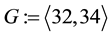

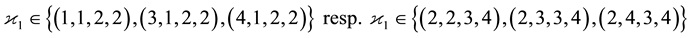

Since computer aided classifications of finite  -groups go back to 1975, fourty years ago, there arises the question why periodic bifurcations did not show up in the earlier literature already. At the first sight, this fact seems incomprehensible, because the smallest two 3-groups which reveal the phenomenon of periodic bifurcations with modest complexity were well known to both, Ascione, Havas and Leedham-Green [14] and Nebelung [15] . Their SmallGroups identifiers are

-groups go back to 1975, fourty years ago, there arises the question why periodic bifurcations did not show up in the earlier literature already. At the first sight, this fact seems incomprehensible, because the smallest two 3-groups which reveal the phenomenon of periodic bifurcations with modest complexity were well known to both, Ascione, Havas and Leedham-Green [14] and Nebelung [15] . Their SmallGroups identifiers are  and

and  (see §9 and [16] [17] ). Due to the lack of systematic identifiers in 1977, they were called the non-CF groups Q and U in ([14] , Table 1, p. 265, and Table 2, p. 266), since their lower central series

(see §9 and [16] [17] ). Due to the lack of systematic identifiers in 1977, they were called the non-CF groups Q and U in ([14] , Table 1, p. 265, and Table 2, p. 266), since their lower central series  has a non-cyclic factor

has a non-cyclic factor

So Ascione and Nebelung were both standing in front of the door to a realm of uncharted waters. The reason why they did not enter this door was the sharp definition of their project targets. A bifurcation is the special case of a 2-fold multifurcation (§8): At a vertex

Ascione’s thesis subject [18] [19] in 1979 was to investigate two-generated 3-groups

The goal of Nebelung’s dissertation [15] in 1989 was the classification of metabelian 3-groups

4. Definitions and terminology

According to Newman ([20] , 2, pp. 52-53), there exist several distinct definitions of the parent

[(P)]

1) the centre

2) the last non-trivial term

3) the last non-trivial term

4) the last non-trivial term

In each case,

In the following, the direction of the canonical projections is selected for all edges. Then, more generally, a vertex

of directed edges from

In the most important special case (P2) of parents defined as last non-trivial lower central quotients, they can also be viewed as the successive quotients

with

Generally, the descendant tree

5. Pro-pgroups and coclass trees

For a sound understanding of coclass trees as a particular instance of descendant trees, it is necessary to sum- marize some facts concerning infinite topological pro-

finite. An infinite pro-

A central finiteness result for infinite pro-

・

・

to

・

The descendant tree

minimal

is called the mainline (or trunk) of the tree.

6. Tree Diagram

Further terminology, used in diagrams visualizing finite parts of descendant trees, is explained in Figure 1 by means of an artificial abstract tree. On the left hand side, a level indicates the basic top-down design of a descendant tree. For concrete trees, such as those in Figure 2, resp. Figure 3, etc., the level is usually replaced by a scale of orders increasing from the top to the bottom. A vertex is capable (or extendable) if it has at least one immediate descendant, otherwise it is terminal (or a leaf). Vertices sharing a common parent are called siblings.

Figure 1. Terminology for descendant trees.

Figure 2. 2-groups of coclass 1.

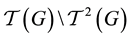

If the descendant tree is a coclass tree

labelled according to the level n, then the finite subtree defined as the difference set

is called the nth branch (or twig) of the tree or also the branch

Figure 1 shows a descendant tree whose branches

If all vertices of depth bigger than a given integer

(depth-)pruned branch

connected by the mainline, whose vertices

Figure 3. 3-groups of coclass 1.

7. Virtual Periodicity

The periodicity of branches of depth-pruned coclass trees has been proved with analytic methods using zeta functions ([22] , 7, Thm.15, p. 280) of groups by du Sautoy ([1] , Thm.1.11, p. 68, and Thm.8.3, p. 103), and with algebraic techniques using cohomology groups by Eick and Leedham-Green [2] . The former methods admit the qualitative insight of ultimate virtual periodicity, the latter techniques determine the quantitative structure.

Theorem 7.1 For any infinite pro-

Proof. The graph isomorphisms of depth-

This central result can be expressed ostensively: When we look at a coclass tree through a pair of blinkers and ignore a finite number of pre-periodic branches at the top, then we shall see a repeating finite pattern (ultimate periodicity). However, if we take wider blinkers the pre-periodic initial section may become longer (virtual periodicity).

The vertex

See Figure 1.

8. Multifurcation and coclass Graphs

Assume that parents of finite

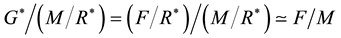

The nuclear rank

・

・ If

・ If

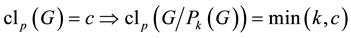

In the last case, a more precise assertion is possible: If G has coclass

Multifurcation is correlated with different orders of the last non-trivial lower central of immediate descendants. Since the nilpotency class increases exactly by a unit,

In this case,

the coclass increases by

descendant with directed edge of depth

If the condition of depth (or step size) 1 is imposed on all directed edges, then the maximal descendant tree

of directed coclass graphs

Coclass Theorems imply that

is the disjoint union of finitely many coclass trees

9. Identifiers

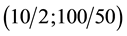

The SmallGroups Library identifiers of finite groups, in particular p-groups, given in the form

in the following concrete examples of descendant trees, are due to Besche, Eick and O’Brien [16] [17] . When the group orders are given in a scale on the left hand side as in Figure 2 and Figure 3, the identifiers are briefly denoted by

Depending on the prime p, there is an upper bound on the order of groups for which a SmallGroup identifier exists, e.g.

and an irregular immediate descendant, connected by an edge of depth

The ANUPQ package [11] containing the implementation of the p-group generation algorithm uses this notation, which goes back to Ascione in 1979 [18] .

10. Concrete Examples of Trees

In all examples, the underlying parent definition (P2) corresponds to the usual lower central series. Occasional differences to the parent definition (P3) with respect to the lower exponent-p central series are pointed out.

10.1. Coclass 0

The coclass graph

of finite p-groups of coclass 0 does not contain a coclass tree and consists of the trivial group 1 and the cyclic group

10.2. Coclass 1

The coclass graph

of finite p-groups of coclass 1 consists of the unique coclass tree with root

abelian p-group of rank 2, and a single isolated vertex (a terminal orphan without proper parent in the same co- class graph, since the directed edge to the trivial group 1 has depth 2), the cyclic group

For

However, the coclass tree of

With the aid of kernels and targets of Artin transfer homomorphisms [3] , the diagrams in Figure 2 and Figure 3 can be endowed with additional information and redrawn as structured descendant trees ([6] , Figure 3.1, p. 419, and Figure 3.2, p. 422).

The concrete examples

by

For

The 2-groups of maximal class, that is of coclass 1, form three periodic infinite sequences:

・ the dihedral groups,

・ the generalized quaternion groups,

・ the semidihedral groups,

For

In contrast to any bigger coclass

Figure 4 shows the interface between finite 3-groups of coclass 1 and 2 of type (3,3).

10.3. Coclass 2

The genesis of the coclass graph

10.3.1. Abelianization of type

As opposed to

For the prime

For odd primes

component

connecting edges of depth 2 of the irregular immediate descendants of

For

Figure 4. 3-groups of coclass 2 with abelianization (3,3).

・ Firstly, there are two terminal Schur

・ Secondly, the two groups

・ And, finally, the three groups

Displaying additional information on kernels and targets of Artin transfers [3] , we can draw these trees as structured descendant trees ([6] , Figure 3.5, p. 439, Figure 3.6, p. 442, and Figure 3.7, p. 443).

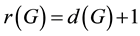

Definition 10.1 Generally, a Schur group (called a closed group by I. Schur, who coined the concept) is a

pro-p group G whose relation rank

inducing the inversion

It should be pointed out that

10.3.2. Pro-3 groups of Coclass 2 with Non-trivial centre

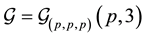

Eick, Leedham-Green, Newman and O’Brien ([24] , 4, Thm.4.1) have constructed a family of infinite pro-3 groups with coclass 2 having a non-trivial centre of order 3. The members are characterized by three parameters

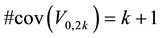

Figure 5 shows some finite 3-groups with coclass 2 and type

10.3.3. Abelianization of type

For

・ Firstly, there are three leaves

・ Secondly, the group

・ And, finally, the three groups

Here, it should be emphasized that

10.3.4. Abelianization of type

For

Table 1. Quotients of the groups

Figure 5. 3-groups of coclass 2 with abelianization (9,3).

This unique tree corresponds to the pro-2 group of the family #59 by Newman and O’Brien ([25] , Appendix A, no. 59, p. 153, Appendix B, Tbl. 59, p. 165), resp. the pro-3 group given by the parameters

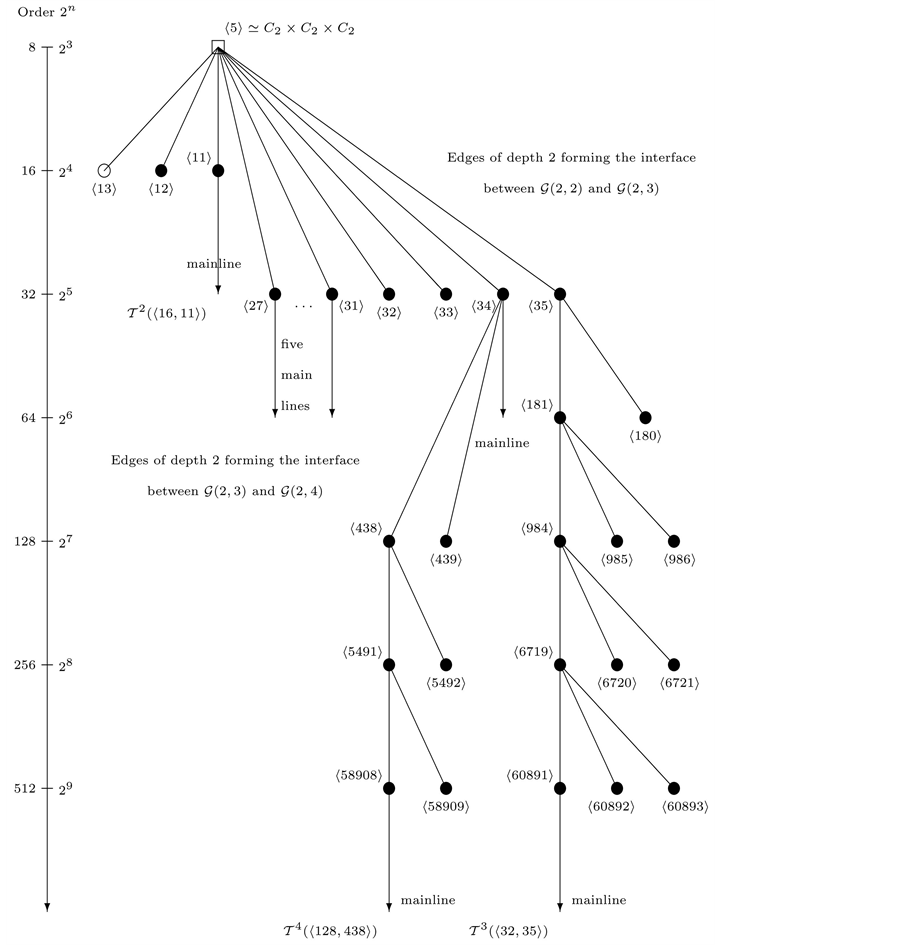

Figure 6 shows some finite 2-groups of coclass 2,3,4 and type (2,2,2).

10.4. Coclass 3

Here again,

10.4.1. Abelianization of type

Since the elementary abelian

Figure 6. 2-groups of coclass 3 with abelianization (2,2,2).

been described in the section about coclass 2. The irregular component

subgraph

irregular immediate descendants of

For

・ the groups

・ the five groups

The trees arising from the capable vertices are associated with infinite pro-2 groups by Newman and O’Brien ([25] , Appendix A, no. 73-79, pp. 154-155, and Appendix B, Tbl. 73-79, pp. 167-168) in the following manner:

The roots of the coclass trees

siblings.

Figure 7. Periodic Bifurcations in

10.4.2. Hall-Senior classification

Seven of these nine top level vertices have been investigated by Benjamin, Lemmermeyer and Snyder ([37] , 2, Tbl. 1) with respect to their occurrence as class-2 quotients

11. History of Descendant Trees

Descendant trees with central quotients as parents (P1) are implicit in Hall’s 1940 paper [30] about isoclinism of groups. Trees with last non-trivial lower central quotients as parents (P2) were first presented by Leedham- Green at the International Congress of Mathematicians in Vancouver, 1974 [20] . The first extensive tree diagrams have been drawn manually by Ascione, Havas and Leedham-Green (1977) [14] , by Ascione (1979) [18] and by Nebelung (1989) [15] . In the former two cases, the parent definition by means of the lower exponent-p central series (P3) was adopted in view of computational advantages, in the latter case, where theoretical aspects were focused, the parents were taken with respect to the usual lower central series (P2).

The kernels and targets of Artin transfer homomorphisms have recently turned out to be compatible with parent-descendant relations between finite p-groups and can favourably be used to endow descendant trees with additional structure [6] .

12. The Construction: p-group Generation algorithm

The p-group generation algorithm by Newman [8] and O’Brien [9] [10] is a recursive process for constructing the descendant tree of an assigned finite p-group which is taken as the root of the tree. It is discussed in some detail in §§13-19.

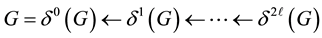

13. Lower Exponent-p Central Series

For a finite p-group G, the lower exponent-p central series (briefly lower p-central series) of

descending series

Since any non-trivial finite p-group

Table 2. Class-2 quotients

group 1 has

The complete lower p-central series of

since

For the convenience of the reader and for pointing out the shifted numeration, we recall that the (usual) lower

central series of

recursively by

As above, for any non-trivial finite

nilpotency of

Thus, the complete lower central series of

since

The following rules should be remembered for the exponent-

Let

[(R)]

1)

2)

3) For any

4) For any

We point out that every non-trivial finite

and ending in the trivial group

elementary abelian

14. p-covering group, p-multiplicator and nucleus

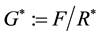

Let

We can certainly find a presentation of

where

elements

are contained in

Now we can define the

and the exact sequence

shows that

the

Let us assume now that the assigned finite

conditions

nucleus of

as a subgroup of the

of

15. Allowable subgroups of the p-multiplicator

As before, let

is a quotient of the

The reason is that there exists an epimorphism

denotes the canonical projection. Consequently, we have

since

epimorphism

In particular, an immediate descendant

of

where

A subgroup

characterization is that

Therefore, the first part of our goal to compile a list of all immediate descendants of

have constructed all allowable subgroups of

where

where

among the immediate descendants.

16. Orbits under extended Automorphisms

Two allowable subgroups

are the corresponding immediate descendants of

Such an isomorphism

has the property that

and thus induces an automorphism

according to the rule (R2), each extended automorphism

to be the permutation group generated by all permutations induced by automorphisms of

are precisely the orbits of allowable subgroups under the action of the permutation group

Eventually, our goal to compile a list

when we select a representative

17. Capable p-groups and step Sizes

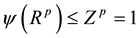

We recall from §6 that a finite p-group G is called capable (or extendable) if it possesses at least one immediate descendant, otherwise it is called terminal (or a leaf). As mentioned in §8 already, the nuclear rank

・ G is terminal if and only if

・ G is capable if and only if

In the case of capability,

of the corresponding allowable subgroup

For the related phenomenon of multifurcation of a descendant tree at a vertex G with nuclear rank

The

18. Numbers of immediate Descendants

We denote the number of all immediate descendants, resp. immediate descendants of step size

metabelian

as given by actual implementations of the

First, let

・ The group

・ The group

・ The group

descendant numbers

Next, let

・ The group

・ The group

・ One of its immediate descendants, the group

In contrast, groups with abelianization of type

・ The group

・ The group

・ The group

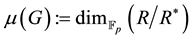

19. Schur multiplier

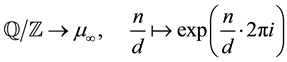

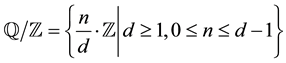

Via the isomorphism

group

can be viewed as the additive analogue of the multiplicative group

of all roots of unity.

Let p be a prime number and G be a finite p-group with presentation

of the G-module

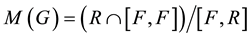

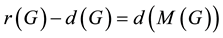

Shafarevich ([38] , 6, p. 146) has proved that the difference between the relation rank

minimal number of generators of the Schur multiplier of G, that is

Boston and Nover ([39] , 3.2, Prop. 2) have shown that

for all quotients

Furthermore, Blackhurst (in the appendix On the nucleus of certain p-groups of a paper by Boston, Bush and Hajir [35] ) has proved that a non-cyclic finite p-group G with trivial Schur multiplier

We conclude this section by giving two examples.

・ A finite p-group G has a balanced presentation

is called a Schur group [7] [34] -[36] and it must be a leaf in the descendant tree

・ A finite p-group G satisfies

and only if it has a non-trivial cyclic Schur multiplier

20. Pruning strategies

For searching a particular group in a descendant tree

[(F)]

1) filtering the

2) eliminating a set of certain transfer kernel types (TKTs, see ([6] , pp. 403-404));

3) cancelling all non-metabelian groups (thus restricting to the metabelian skeleton);

4) removing metabelian groups with cyclic centre (usually of higher complexity);

5) cutting off vertices whose distance from the mainline (depth) exceeds some lower bound;

6) combining several different sifting criteria.

The result of such a sieving procedure is called a pruned descendant tree

However, in any case, it should be avoided that the mainline of a coclass tree is eliminated, since the result would be a disconnected infinite set of finite graphs instead of a tree. We expand this idea further in the following detailed discussion of new phenomena.

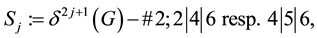

21. Striking News: periodic bifurcations intrees

We begin this section about brand-new discoveries with the most recent example of periodic bifurcations in trees of 2-groups. It has been found on the 17th of January 2015, motivated by a search for metabelian 2-class tower groups [40] of complex quadratic fields [41] and complex bicyclic biquadratic Dirichlet fields [42] .

21.1. Finite 2-Groups G with

The 2-groups under investigation are three-generator groups with elementary abelian commutator factor group of type

Remark 21.1 Since our primary intention is to provide a sound group theoretic background for several phe- nomena discovered in class field theory and algebraic number theory, we eliminated superfluous brushwood in the descendant trees to avoid unnecessary complexity.

The selected sifting process for reducing the entire descendant tree

1) omitting all the 14 terminal step size-2 descendants, and 5, resp. 4, of the 6 capable step size-2 descendants, together with their complete descendant trees, in Theorem 21.1, resp. Corollary 21.1, and

2) eliminating all, resp. 4, of the 5 terminal step size-1 descendants in Theorem 21.1, resp. Corollary 21.1.

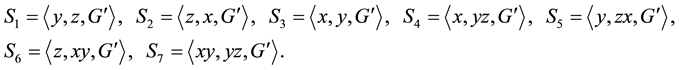

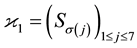

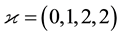

Denote by

Just within this subsection, we select a special designation for a TKT [[6] , p. 403-404] whose first layer consists exactly of all these seven planes in the 3-dimensional

Definition 21.1 The transfer kernel type (TKT)

members of the first layer

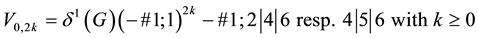

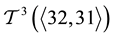

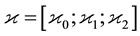

For brevity, we give 2-logarithms of abelian type invariants in the following theorem and we denote iteration

by formal exponents, for instance,

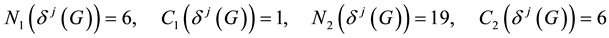

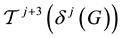

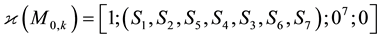

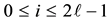

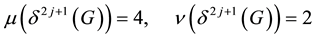

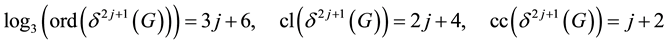

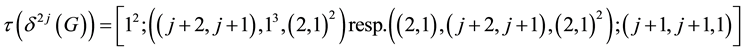

Theorem 21.1 Let

1) In the descendant tree

of (reverse) directed edges with uniform step size 2 such that

(along the path,

of this path share the following common invariants:

・ the transfer kernel type with layer

first component which is total,

・ the 2-multiplicator rank and the nuclear rank, giving rise to the bifurcation,

・ and the counters of immediate descendants,

determining the local structure of the descendant tree.

2) A few other invariants of the vertices

・ the 2-logarithm of the order, the nilpotency class and the coclass,

・ a single component of layer

In view of forthcoming number theoretic applications, we add the following

Corollary 21.1 Let

1) The regular component

contains a unique periodic sequence whose vertices

rized by a permutation TKT

with a single fixed point

2) The irregular component

unique second coclass tree

with

share the TKT in Equation (44).

Proof. (of Theorem 21.1, Corollary 21.1 and Theorem 21.2)

The

defined as the disjoint union of all pruned coclass trees

[2] of each coclass tree

vertical construction was terminated at nilpotency class 12, considerably deeper than the point where periodicity sets in. The horizontal construction was extended up to coclass 13, where the amount of CPU time started to become annoying.

Within the frame of our computations, the periodicity was not restriced to bifurcations only: It seems that the pruned (or maybe even the entire) descendant trees

The extent to which we constructed the pruned descendant tree suggests the following conjecture.

Conjecture 21.1 Theorem 21.1, Corollary 21.1 and Theorem 21.2 remain true for an arbitrarily large positive integer

Remark 21.2 We must emphasize that the root

only, and that the mainline of the coclass tree

・ its root is not a descendant of

・ the TKT of its vertices

is a permutation with 5 fixed points and only a single 2-cycle

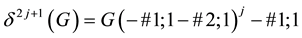

One-parameter polycyclic pc-presentations for all occurring groups are given as follows.

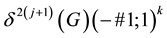

1) For the mainline vertices of the coclass tree

2) For the mainline vertices of the coclass tree

3) For the mainline vertices of the coclass tree

Theorem 21.2 For higher coclass

To obtain a presentation for the vertices

periodic sequence whose vertices are characterized by the permutation TKT (49), we must only add the single

relation

Theorem 21.2.

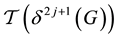

21.2. Finite 3-groups G with

We continue this section with periodic bifurcations in trees of 3-groups, which have been discovered in 2012 and 2013 [45] -[47] , inspired by a search for 3-class tower groups of complex quadratic fields [7] [48] [49] , which must be Schur

These 3-groups are two-generator groups of coclass at least 2 with elementary abelian commutator quotient of type

The two groups

Denote by

Within this subsection, we make use of special designations for transfer kernel types (TKTs) which were defined generally in [[6] , p. 403-404] and more specifically for the present scenario in [4] [50] .

We are interested in the unavoidable mainline vertices with TKTs c.18,

We point out that, for instance

Remark 21.3 We choose the following sifting strategy for reducing the entire descendant tree

1) keeping all of the 3 terminal step size-2 descendants, which are exactly the Schur

2) eliminating 2 of the 5 terminal step size-1 descendants having TKT

For brevity, we give 3-logarithms of abelian type invariants in the following theorem and we denote iteration

by formal exponents, for instance,

Theorem 21.3 Let

1) In the descendant tree

of (reverse) directed edges of alternating step sizes 1 and 2 such that

resp. all the vertices with odd superscript

of this path share the following common invariants, respectively:

・ the uniform (w.r.t. i) transfer kernel type, containing a total component

・ the 2-multiplicator rank and the nuclear rank,

resp., giving rise to the bifurcation for odd

・ and the counters of immediate descendants,

resp.

determining the local structure of the descendant tree.

2) A few other invariants of the vertices

・ the 3-logarithm of the order, the nilpotency class and the coclass,

resp.

・ a single component of layer

resp.

Theorem 21.3 provided the scaffold of the pruned descendant tree

with mainlines and periodic bifurcations.

With respect to number theoretic applications, however, the following Corollaries 21.2 and 21.3 are of the greatest importance.

Corollary 21.2 Let

Whereas the vertices with even superscript

links in the distinguished path, the vertices with odd superscript

1) The regular component

contains the mainline,

which entirely consists of

are

with layer

which deviate from the mainline TKT of Equation (58) in a single component only.

2) The irregular component

contains a bunch of 3 isolated Schur

which possess the same TKTs as in Equation (67), and additionally contains the root of the next coclass tree

with

The metabelian 3-groups forming the three distinguished periodic sequences

of the pruned coclass tree

descendants up to now.) Since all groups in

dants can be defined in the following way.

Definition 21.2 Let

Corollary 21.3 For

finite cover of cardinality

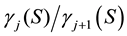

The arrows in Figure 8 and Figure 9 indicate the projections

Proof. (of Theorem 21.3, Corollary 21.2, Corollary 21.3 and Theorem 21.4)

The

descendants

irregular component

periodicity [1] [2] of each pruned coclass tree

construction was terminated at nilpotency class 19, considerably deeper than the point where periodicity sets in. The horizontal construction was extended up to coclass 10, where the consumption of CPU time became daunting.

Within the frame of our computations, the periodicity was not restriced to bifurcations only: It seems that the

pruned (or maybe even the entire) descendant trees

graphs. This is visualized impressively by Figure 8 and Figure 9, where the following notation (not to be confused with layers) is used

resp.

Figure 8. Periodic bifurcations in

Similarly as in the previous section, the extent to which we constructed the pruned descendant trees suggests the following conjecture.

Conjecture 21.2 Theorem 21.3, Corollary 21.2 and Corollary 21.3 remain true for an arbitrarily large positive integer

Figure 9. Periodic bifurcations in

One-parameter polycyclic pc-presentations for the groups in the first three pruned coclass trees of

1) For the metabelian vertices of the pruned coclass tree

2) For the non-metabelian vertices of the pruned coclass tree

the Schur

3) For the non-metabelian vertices of the pruned coclass tree

the Schur

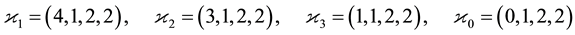

The parameter

・ the location of the group on the descendant tree, and

・ the transfer kernel type (TKT) of the group, as follows:

whereas all the other groups belong to periodic sequences or are isolated Schur

In Figure 10, resp. Figure 11, we have drawn the lattice of normal subgroups of

The upper and lower central series,

Generators

individual isomorphism types and placed in locations which illustrate the structure of the groups. Furthermore, the normal lattice of the metabelianization

We conclude with a theorem concerning the central series and some fundamental properties of the Schur

Theorem 21.4

Let

1) the factors of their upper central series are given by

Figure 10. Normal Lattice and Central Series of

2) their second derived group

Furthermore,

・ they are Schur

・ the factors of their lower central series are given by

Figure 11. Normal Lattice and Central Series of

・ their metabelianization

・ their biggest metabelian ancestor, that is the

22. Conclusion

We emphasize that the results of Section 21.2 provide the background for considerably stronger assertions than those made in [7] (which are, however, sufficient already to disprove erroneous claims in [48] [49] ). Firstly, they concern four TKTs E.6, E.14, E.8 and E.9 instead of just TKT E.9, and secondly, they apply to varying odd nilpotency class

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge that our research is supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): P 26008-N25. We are indebted to the anonymous referees for valuable suggestions improving the exposition and readability.

Cite this paper

Daniel C.Mayer, (2015) Periodic Bifurcations in Descendant Trees of Finite <i>p</i>-Groups。 Advances in Pure Mathematics,05,162-195. doi: 10.4236/apm.2015.54020

References

- 1. du Sautoy, M. (2001) Counting p-Groups and Nilpotent Groups. Publications Mathématiques de l’Institut des Hautes études Scientifiques, 92, 63-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02698914

- 2. Eick, B. and Leedham-Green, C. (2008) On the Classification of Prime-Power Groups by Coclass. Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society, 40, 274-288. http://dx.doi.org/10.1112/blms/bdn007

- 3. Artin, E. (1929) Idealklassen in Oberkorpern und allgemeines Reziprozitatsgesetz. Abhandlungen aus dem Mathematischen Seminar der Universitat Hamburg, 7, 46-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02941159

- 4. Mayer, D.C. (2012) Transfers of Metabelian p-Groups. Monatshefte für Mathematik, 166, 467-495. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00605-010-0277-x

- 5. Mayer, D.C. (2014) Principalization Algorithm via Class Group Structure. Journal de Théorie des Nombres de Bordeaux, 26, 415-464.

- 6. Mayer, D.C. (2013) The Distribution of Second p-Class Groups on Coclass Graphs. Journal de Théorie des Nombres de Bordeaux, 25, 401-456.

- 7. Bush, M.R. and Mayer, D.C. (2015) 3-Class Field Towers of Exact Length 3. Journal of Number Theory, 147, 766-777. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jnt.2014.08.010

- 8. Newman, M.F. (1977) Determination of Groups of Prime-Power Order. In: Bryce, R.A., Cossey, J., Newman, M.F., Eds., Group Theory, Springer, Berlin, 73-84.

- 9. O’Brien, E.A. (1990) The p-Group Generation Algorithm. Journal of Symbolic Computation, 9, 677-698. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0747-7171(08)80082-X

- 10. Holt, D.F., Eick, B. and O’Brien, E.A. (2005) Handbook of Computational Group Theory, Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications. Chapman and Hall/CRC Press, Boca Raton. http://dx.doi.org/10.1201/9781420035216

- 11. Gamble, G., Nickel, W. and O’Brien, E.A. (2006) ANU p-Quotient—p-Quotient and p-Group Generation Algorithms. An Accepted GAP 4 Package, Available also in MAGMA.

- 12. The GAP Group (2014) GAP—Groups, Algorithms, and Programming—A System for Computational Discrete Algebra. Version 4.7.5, Aachen, Braunschweig, Fort Collins, St. Andrews. http://www.gap-system.org

- 13. The MAGMA Group (2014) MAGMA Computational Algebra System. Version 2.21-1, Sydney. http://magma.maths.usyd.edu.au

- 14. Ascione, J.A., Havas, G. and Leedham-Green, C.R. (1977) A Computer Aided Classification of Certain Groups of Prime Power Order. Bulletin of the Australian Mathematical Society, 17, 257-274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s0004972700010467

- 15. Nebelung, B. (1989) Klassifikation metabelscher 3-Gruppen mit Faktorkommutatorgruppe vom Typ (3,3) und Anwendung auf das Kapitulationsproblem. Inaugural Dissertation, Universitat zu Koln, Koln.

- 16. Besche, H.U., Eick, B. and O’Brien, E.A. (2002) A Millennium Project: Constructing Small Groups. International Journal of Algebra and Computation, 12, 623-644. http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S0218196702001115

- 17. Besche, H.U., Eick, B. and O’Brien, E.A. (2005) The Small Groups Library—A Library of Groups of Small Order. An Accepted and Refereed GAP 4 Package, Available also in MAGMA.

- 18. Ascione, J.A. (1979) On 3-Groups of Second Maximal Class. Ph.D. Thesis, Australian National University, Canberra.

- 19. Ascione, J.A. (1980) On 3-Groups of Second Maximal Class. Bulletin of the Australian Mathematical Society, 21, 473-474. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0004972700006298

- 20. Newman, M.F. (1990) Groups of Prime-Power Order. Lecture Notes in Mathematics, 1456, 49-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BFb0100730

- 21. Leedham-Green, C.R. and Newman, M.F. (1980) Space Groups and Groups of Prime Power Order I. Archiv der Mathematik, 35, 193-203. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01235338

- 22. du Sautoy, M. and Segal, D. (2000) Zeta Functions of Groups. In: du Sautoy, M., Segal, D. and Shalev, A., Eds., New Horizons in Pro-p Groups, Progress in Mathematics, Birkhauser, Basel, 249-286.

- 23. Leedham-Green, C.R. and McKay, S. (2002) The Structure of Groups of Prime Power Order, London Mathematical Society Monographs. New Series 27, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- 24. Eick, B., Leedham-Green, C.R., Newman, M.F. and O’Brien, E.A. (2013) On the Classification of Groups of Prime-Power Order by Coclass: The 3-Groups of Coclass 2. International Journal of Algebra and Computation, 23, 1243-1288. http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/s0218196713500252

- 25. Newman, M.F. and O’Brien, E.A. (1999) Classifying 2-Groups by Coclass. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 351, 131-169. http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/S0002-9947-99-02124-8

- 26. Dietrich, H., Eick, B. and Feichtenschlager, D. (2008) Investigating p-Groups by Coclass with GAP. In: Kappe, L.-C., Magidin, A. and Morse, R.F., Eds., Computational Group Theory and the Theory of Groups, AMS, Providence, 45-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/conm/470/09185

- 27. Shalev, A. (1994) The Structure of Finite p-Groups: Effective Proof of the Coclass Conjectures. Inventiones Mathematicae, 115, 315-345. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01231763

- 28. Leedham-Green, C.R. (1994) The Structure of Finite p-Groups. Journal London Mathematical Society, 50, 49-67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1112/jlms/50.1.49

- 29. Hall, M. and Senior, J.K. (1964) The Groups of Order 2n (n ≤ 6). Macmillan, New York.

- 30. Hall, P. (1940) The Classification of Prime-Power Groups. Journal für Die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik, 182, 130-141.

- 31. Blackburn, N. (1958) On a Special Class of p-Groups. Acta Mathematica, 100, 45-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02559602

- 32. Taussky, O. (1937) A Remark on the Class Field Tower. Journal London Mathematical Society, 12, 82-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1112/jlms/s1-12.1.82

- 33. Bagnera, G. (1898) La composizione dei gruppi finiti il cui grado è la quinta potenza di un numero primo. Annali di Matematica Pura ed Applicata, 1, 137-228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/bf02419191

- 34. Arrigoni, M. (1998) On Schur σ-Groups. Mathematische Nachrichten, 192, 71-89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mana.19981920105

- 35. Boston, N., Bush, M.R. and Hajir, F. (2015) Heuristics for p-Class Towers of Imaginary Quadratic Fields. Mathematische Annalen, in Press.

- 36. Koch, H. and Venkov, B.B. (1975) über den p-Klassenkorperturm eines imaginar-quadratischen Zahlkorpers. Astérisque, 24-25, 57-67.

- 37. Benjamin, E., Lemmermeyer, F. and Snyder, C. (2003) Imaginary Quadratic Fields with Cl2(k)(2,2,2). Journal of Number Theory, 103, 38-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-314X(03)00084-2

- 38. Shafarevich, I.R. (1964) Extensions with Prescribed Ramification Points (Russian). Publications Mathématiques de l’IHéS, 18, 71-95.

- 39. Boston, N. and Nover, H. (2006) Computing Pro-p Galois Groups. Algorithmic Number Theory: Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 4076, 1-10.

- 40. Mayer, D.C. (2012) The Second p-Class Group of a Number Field. International Journal of Number Theory, 8, 471-505. http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S179304211250025X

- 41. Nover, H. (2009) Computation of Galois Groups of 2-Class Towers. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

- 42. Azizi, A., Zekhnini, A. and Taous, M. (2015) Coclass of for Some Fields with 2-Class Groups of Type (2,2,2). Journal of Algebra and Its Applications, in Press.

- 43. Bosma, W., Cannon, J. and Playoust, C. (1997) The Magma Algebra System. I. The User Language. Journal of Symbolic Computation, 24, 235-265. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jsco.1996.0125

- 44. Bosma, W., Cannon, J.J., Fieker, C. and Steels, A., Eds. (2014) Handbook of Magma Functions. Edition 2.21, University of Sydney, Sydney.

- 45. Mayer, D.C. and Newman, M.F. (2013) Finite 3-Groups as Viewed from Class Field Theory, Groups St. Andrews 2013. University of St. Andrews, Fife, Scotland.

- 46. Mayer, D.C., Bush, M.R. and Newman, M.F. (2013) 3-Class Field Towers of Exact Length 3. 18th OMG Congress and 123rd Annual DMV Meeting 2013, University of Innsbruck, Tyrol, Austria.

- 47. Mayer, D.C., Bush, M.R. and Newman, M.F. (2013) Class Towers and Capitulation over Quadratic Fields. West Coast Number Theory 2013, Asilomar Conference Center, Pacific Grove.

- 48. Scholz, A. and Taussky, O. (1934) Die Hauptideale der kubischen Klassenkorper imaginar quadratischer Zahlkorper: Ihre rechnerische Bestimmung und ihr Einflu auf den Klassenkorperturm. Journal Für Die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik, 171, 19-41.

- 49. Heider, F.-P. and Schmithals, B. (1982) Zur Kapitulation der Idealklassen in unverzweigten primzyklischen Erweiterungen. Journal Für Die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik, 336, 1-25.

- 50. Mayer, D.C. (1991) Principalization in Complex S3-Fields. Congressus Numerantium, 80, 73-87.