Advances in Pure Mathematics

Vol.04 No.09(2014), Article ID:49935,3 pages

10.4236/apm.2014.49059

A Simple and General Proof of Beal’s Conjecture (I)

Golden Gadzirayi Nyambuya

Department of Applied Physics, National University of Science and Technology, Bulawayo, Republic of Zimbabwe

Email: physicist.ggn@gmail.com

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 15 July 2014; revised 15 August 2014; accepted 1 September 2014

ABSTRACT

Using the same method that we used in [1] to prove Fermat’s Last Theorem in a simpler and truly marvellous way, we demonstrate that Beal’s Conjecture yields—in the simplest imaginable manner, to our effort to prove it.

Keywords:

Fermat’s Last Theorem, Beal’s conjecture, Proof

1. Introduction

“Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.”—Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519).

Beal’s Conjecture is a conjecture in number theory formulated in 1993 while investigating generalizations of Fermat’s Last Theorem set forth in 1997 as a Prize Problem by the United States of America’s Dallas, Texas number theory enthusiast and billionaire banker, Mr. Daniel Andrew Beal [2] . As originally stated, the con- jecture asserts that:

Beal’s Conjecture:

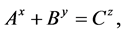

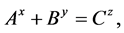

If,

(1)

(1)

and

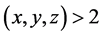

and  are positive integers with

are positive integers with , then

, then  and

and  have a common prime factor.

have a common prime factor.

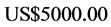

For a correct proof or counterexample published in an internationally renowned and refereed mathematics journal, Mr. Beal initially offered a Prize of  in 1997, raising it to

in 1997, raising it to  over ten years by adding

over ten years by adding  each year over the ten-year period [2] . Very recently, Andrew Beal upped the stacks and has raised1 it beyond the initial projection of

each year over the ten-year period [2] . Very recently, Andrew Beal upped the stacks and has raised1 it beyond the initial projection of  to

to .

.

Herein, we lay down a complete proof of the conjecture not so much for the very “handsome’’ prize money attached to it, but more for the sheer intellectual challenge that the philanthropist—Mr. Andrew Beal, has placed before humanity. We believe that challenges without flinching—must be tackled heard-on, without fear of failure.

From intuition, we strongly believe or feel that a direct proof of the original statement of Beal conjecture as stated in (1) would be difficult if not impossible to procure. We have to recast this statement into an equivalent form and proceed to a proof by way of contradiction. The equivalent statement to (1) is [2] :

Beal’s Conjecture (Recast):

The equation,

(2)

(2)

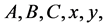

admits no solutions for any positive integers  and

and  with

with  for any piecewise co- prime triple

for any piecewise co- prime triple  and

and

In its recast form (2), it becomes clear that Beal’s conjecture is a generalization of Fermat’s Last Theorem [3] where Fermat’s Last Theorem is the special case of Beal’s conjecture where

The proof that we present demonstrates that the triple

The synopsis of this reading is as follows. In §(2), we provide a pivotal lemma that is necessary for our argument. In §(3), we provide the short proof of Beal’s Conjecture and thereafter in §(4), we give a general discussion and the conclusion drawn thereof.

2. Lemma

If

The above statement is clearly evident and needs no proof. Below we demonstrate that this statement is true. This demonstration does not constitute a proof.

What this statement really means is that the number

since one can always find some

in which case we will have p = ag and

Setting

3. Proof

The proof that we are going to provide is a proof by contradiction and this proof makes use of Lemma §(2) whereby we demonstrate that the triple

to be true for some piecewise co-prime triple

First, we must realise that if just one of the members of the triple

Now, for our proof, by way of contradiction, we assert that there exists a set of positive integers

If the statement (7) holds true, then—clearly; there must exist some

Now, according to the Lemma §(2), the equation

From (9), it is clear that

and sacrosanct assumption that

Alternatively, according to the Lemma §(2), the equation

this equation, can always be written such that

Now, substituting

Again, from (10), it is clear that

Therefore, by way of contradiction, Beal’s Conjecture is true since we arrive at a contradictory result that

4. Discussion

At present, it appears that there has not been found a general proof of Beal’s conjecture, only partial solutions exist. For example, the case

Our thrust has been on a direct proof and just as the proof presented in the reading [1] , the proof here provided is simple, general and all-encompassing. It covers all possible cases. Clearly, the present proof applies elementary methods of arithmetic that where available even in the days of Fermat. At this point, if anything, we only await the judgement of the world of mathematics as to whether this proof is correct or not. Without any oversight on our confidence in our proof, allow us to say that, until such a time that evidence to the contrary is brought forth, we are at any rate, convinced of the correctness of the proof here presented.

We have presented another proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem in the reading [10] and this proof makes use of the method of Pythagorean triples. This proof is much longer than the proof using the methods presented herein. We will be presenting a second version of the proof of Beal’s Conjecture using the method of Pythagorean triples used in [10] .

5. Conclusion

We hereby make the following conclusion that if our proof is correct as we strongly believe, then, Beal’s Conjecture seizes to be a conjecture but forthwith transforms into a fully-fledged theorem as a logically and mathematically correct proof has now been supplied.

References

- Nyambuya, G.G. (2014) On a Simpler, Much More General and Truly Marvellous Proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem (I). http://vixra.org/abs/1309.0154

- Daniel Mauldin, R. (1997) A Generalization of Fermat’s Last Theorem: The Beal Conjecture and Prize Problem. Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 44, 1436-1439.

- Wiles, A. (1995) Modular Elliptic Curves and Fermat’s Last Theorem. Annals of Mathematics, 141, 443-551. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2118559

- Poonen, B., Schaefer, E.F. and Stoll, M. (2007) Twists of X(7) and Primitive Solutions to x2 + y3 = z7. Duke Mathematical Journal, 137, 103-158. http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/S0012-7094-07-13714-1

- Crandall, R. and Pomerance, C. (2000) Prime Numbers: A Computational Perspective. Spinger Science & Business Media, Berlin, 147.

- Siksek, S. and Stoll, M. (2014) The Generalised Fermat Equation x2 + y3 = z15. Archiv der Mathematik, 102, 411-421. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00013-014-0639-z

- Dahmen, S.R. and Siksek, S. (2014) Perfect Powers Expressible as Sums of Two Fifth or Seventh Powers. arXiv: 1309.4030v2.

- Darmon, H. and Granville, A. (1995) On the Equations zm = F(x, y) and Axp + Byq = Czr. Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society, 27, 513-543. http://dx.doi.org/10.1112/blms/27.6.513

- Thiagarajan, R.C. (2014) A Proof to Beal’s Conjecture. Bulletin of Mathematical Sciences & Applications, 89-93.

- Nyambuya, G.G. (2014) On a Simpler, Much More General and Truly Marvellous Proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem (II). http://vixra.org/abs/1405.0023

NOTES

1The Beal Prize, AMS, http://www.ams.org/profession/prizes-awards/ams-supported/beal-prize